Holly Tucker's Blog, page 17

March 15, 2016

Fighting the Legend of the “Lobotomobile”

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

I often receive emails from middle school and high school students working on projects about the history of lobotomy, a now obsolete but once mainstream form of brain surgery intended to treat psychiatric illnesses. Between 1936 and the 1970s, between 40,000 and 50,000 Americans underwent this debilitating and rarely beneficial form of treatment. The young researchers write to me because I’m the author of The Lobotomist, a biography of the lobotomy advocate Walter Freeman. My book tells the story of the lobotomy’s development and sets the infamous procedure in the context of the history of psychiatric treatments and the life of its promoter.

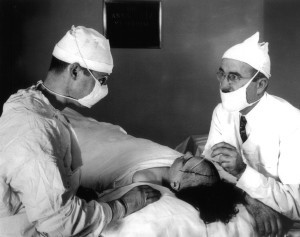

Walter Freeman (right) performing a prefrontal lobotomy with his surgical partner, James Watts

Last week a student asked me to confirm a claim she had read online that Freeman, a devoted cross-country traveler who often undertook long trips to visit his former patients, called his camper-van and mobile office a “lobotomobile.” As much as I admire the cleverness and appropriateness of that term, I had to tell her that Freeman neither coined nor used that name for his vehicle. The nickname didn’t appear until a decade after Freeman’s death.

I’ve wondered whether as Freeman’s biographer I bear the responsibility to fight the persistent appearance of this legend or others associated with the lobotomist’s career, such as the myths that authorities stripped him of his medical license and that he performed lobotomies with a gold-plated ice pick. They’re all fictions, and they are so widespread it would be a gigantic if not impossible task to beat them down.

The misinformation about the “lobotomobile,” for instance, appears in Freeman’s Wikipedia page, in the Encyclopedia Britannica and Damn Interesting blogs, and in several books, as well as in countless other articles, blogs, and publications. The “lobotomobile” nickname even inspired a short movie by the Canadian filmmaker Sara St. Onge. While I enjoy watching this entertaining musical, I suspect it encourages viewers to believe that “lobotomobile” was a name that Freeman actually used.

The word is found nowhere in Freeman’s voluminous published and unpublished writings, including the correspondence, autobiography, memos, and notes he left to the archives at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Its earliest appearance in print seems to be in an account of one of Freeman’s patient-tracking road trips on page 246 of David Shutts’s 1982 book Lobotomy: Resort to the Knife: “Still uncomfortable from surgery but able to drive, he headed southeast in a newly purchased camper-bus, which could be described as his ‘lobotomobile.’” Shutts’s usage suggests that he invented the word himself.

Perhaps the best way to explain the stubbornness of the myth of Freeman’s “lobotomobile” name is that it efficiently (although falsely) casts the physician as a monster who not only damaged patients’ brains but also mocked them by giving a flippantly humorous title to the van he used to conduct part of his grisly business. Clearly many people want to believe such a thing. But my research has convinced me that Freeman’s patients were too important to him — for reasons rooted in his compassion, hubris, and narcissism— to make fun of them in that way.

In the end, I’ve decided that I don’t have to confront all the wrong statements put out there about my biographical subject. I’ve written a book that offers my perspective of the man in all the complexity of his virtues and failings. Isn’t that enough?

For more information

PBS American Experience documentary The Lobotomist (2008)

March 14, 2016

‘A house crammed full of books’ – and children

by Helen King (monthly contributor)

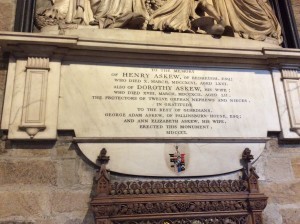

How are you at combining your work and your family? It’s a question which exercises many of us, and it came to mind again last week. I’ve always liked visiting cathedrals, and I’ve always been interested in funerary monuments. So on a trip to north-east England, when I was briefly in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, I made a point of revisiting the Anglican Cathedral there. I was struck by one particular monument and wanted to know the story behind it. It’s an unusual monument because it commemorates a childless man and his wife, Henry (d. 1796) and Dorothy (d. 1792) Askew, who took in twelve – twelve! – orphaned children.

How are you at combining your work and your family? It’s a question which exercises many of us, and it came to mind again last week. I’ve always liked visiting cathedrals, and I’ve always been interested in funerary monuments. So on a trip to north-east England, when I was briefly in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, I made a point of revisiting the Anglican Cathedral there. I was struck by one particular monument and wanted to know the story behind it. It’s an unusual monument because it commemorates a childless man and his wife, Henry (d. 1796) and Dorothy (d. 1792) Askew, who took in twelve – twelve! – orphaned children.

The monument doesn’t explain why this happened, so I started digging. It turns out that Henry Askew was one of four sons of Dr Adam Askew and his wife Anne. Adam’s eldest son, Anthony, followed him into the medical profession. After the death of Anthony’s first wife, he married his second wife, Elizabeth. She died in 1773, and Anthony himself died in 1774 at the age of 52. The couple left six sons, and six daughters. It must then be these children who were taken in by their uncle Henry.

One of the children, Ann-Elizabeth, named as one of the two people dedicating this monument to “the best of guardians”, went on to marry the other dedicator, her cousin George-Adam, the son and heir of the youngest of another of the four Askew brothers, John. This makes the family tree rather complicated. Ann-Elizabeth and George-Adam married in 1795, three years after Ann-Elizabeth’s foster mother Dorothy died, one year after John died, and the year before Henry’s own death.

One of the children, Ann-Elizabeth, named as one of the two people dedicating this monument to “the best of guardians”, went on to marry the other dedicator, her cousin George-Adam, the son and heir of the youngest of another of the four Askew brothers, John. This makes the family tree rather complicated. Ann-Elizabeth and George-Adam married in 1795, three years after Ann-Elizabeth’s foster mother Dorothy died, one year after John died, and the year before Henry’s own death.

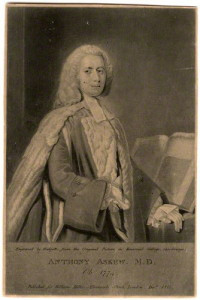

This was a very medical family. As well as Adam and Anthony, the generous Henry also practised medicine. But one of those men is famous for something else too. Anthony Askew was a very famous bibliophile. He collected not only medical books, but early editions of Greek and Roman writers. After his death in 1774, the books from his exceptional library were put up for auction in spring 1775.

It was said of Anthony Askew that he “made bibliomania fashionable”. Some of his books were bought by William Hunter, others by the Kings of France and England, and others by the British Museum, so it’s possible I’ve used some myself when doing research in the British Library. His manuscripts were sold at a separate auction in 1785. The Royal College of Physicians’ account of his life says that “His house was crammed full of books, the passages were full, the very garrets overflowed, and the wags of the day used to say that the half of the square itself would have done so before the book appetite of Dr. Askew would have been satiated.” He’s clearly a man after my own heart.

by Thomas Hodgetts, published for William Richard Beckford Miller, after Allan Ramsay, mezzotint, published December 1811

The account goes on to confirm that “Dr. Askew was twice married: 1st, to Margaret, daughter of Cuthbert Swinburn, esq., of Long Witton, and the Westgate in Northumberland, but had no issue by her; 2ndly, to Elizabeth, daughter of Robert Holford, esq., a master in chancery, by whom he had six sons and six daughters.”

And that’s it. No mention of what happened to those children at his death, and no mention of how twelve children and a book collection managed to co-exist. He seems to have two separate lives: the bibliophile and collector, and the father of twelve. Reference works tell you all about the former, but nothing of the latter. Yet Anthony Askew is just one person! And I’d love to know more about how his family life worked.

March 11, 2016

Harlequins and French Leftovers: From Class to Crass

By Thomas Parker (regular contributor)

This month, I interviewed Harvard’s Janet Beizer about her new book project. It reveals a less savory slice of French culinary history hidden for almost 100 years. The subject? Leftovers.

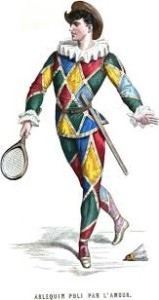

Harlequins being sold at market

Thomas Parker: I remember being in a Parisian Michelin starred restaurant many ago and how appalled the waiters were when my stepmother asked for a doggy bag. I didn’t know the French did leftovers. But that is the subject of your new book project: Harlequins. Is that an English or French term?

Janet Beizer: Well, I think I’m the first person, in all due modesty, to use it in English. It’s a French term, but it’s hard to find people in France who know what they are. There is no translation in English, except “leftovers,” which really doesn’t describe the institution. So I’ve taken the term “arlequin,” which translated literally is “harlequin,” because I think the theatrical term (the harlequin is a Commedia dell’arte character, traditionally dressed in a diamond-pattern costume) is connected to the food.

Thomas: And these were leftovers….

Janet: Exactly. Harlequins were re-plated food leftovers. They began as food from wealthy homes or mansions, townhouses (hôtels particuliers) and fine restaurants swept away in the wee hours of the morning. The butlers and the valets in the kitchen sold off the leftovers after dipping into them themselves, and maybe giving some to the dogs.

Thomas: Is this something they did on the sly?

Janet: My sense is that the owners turned their heads: the leftovers were the tip. Anyway, the lavishness was a part it all. It was so important to display your opulence, and the lavish spreads generated lots of leftovers.

Some of it was in good shape. Some of it was pretty nibbled at. It also depended on where it came from. It could come from an emperor or king’s table, depending on the era, or from a restaurant…

Thomas: So this practice went on in the 19th the 20th century?

Janet: Perhaps further into the twentieth century than we’d care to know. Definitely up until World War One. I think that there wasn’t much opulence during and after World War One…

Postcard displaying a marchande d’arlequins, clients, and dog

Tom: So how did these leftovers made it to market?

Janet: The leftovers would be transported to Les Halles (Paris’ biggest fresh food market until it closed down in 1971). They would be taken underground, which is where all of the sketchy sorts of activities happened. Later on under the Second Empire it was all theoretically regulated, and there were inspectors, but… Butter was colored and mixed with artificial ingredients. Animals were cut up and the food was sometimes doctored. If you read Zola’s The Belly of Paris (1873), you learn how they stuffed the pigeons right before they were killed, infusing them with water and grain so they would be all pumped up.

View of Les Halles from Saint-Eustache by Félix Benoist, circa 1870

Tom: Then the leftovers were sold, above in the Les Halles market?

Janet: Yes. Specialized merchants, usually women, were the marchandes d’arlequins. They would make these plates, prettifying the remains, adding herbs, loads of parsley and mayonnaise to hide the tooth marks. Today you can go into a café in Paris and order an assiette composée; I think of the harlequin plates as assiettes décomposées…

Postcard displaying market ambiance at the turn of the century

Sometimes they built them around a lobster claw, or a beef bone, and the prices would vary, depending on how much meat was on the bone. A plate with just potatoes and cabbage would go for very little.

Tom: So you would buy the whole plate, this platter with a lobster claw, and take it home. Would you admit to your family and guests where you had got the food?

Janet: It depends. There were really poor people who did this, partly because they had the fantasy of eating the emperor’s food. But there were bourgeois people as well because the plates didn’t cost any more than buying the raw ingredients for an ordinary bourgeois meal and cooking them.

Tom: So fascinating…

Janet: And, so, I think it is how French cuisine got codified, because it filtered down the whole spectrum. People learned what fancy food was by buying leftovers in the market. They got a chance to taste it or at least experience the skeletal outlines of what it was…

Tom: But I’m guessing that you wouldn’t want to be caught buying one of these platters.

Janet: Exactly. In Zola, people are described as looking around furtively to make sure they weren’t being watched…And the pretense would be that you were buying this for your pet.

Tom: Except the lobster claw… it would take a very clever dog to do the shucking.

Janet: (Laughs). But the reason it was a called a “harlequin,” was the reference to the Commedia dell’arte and the figure who wore the checkered costume. At the beginning, during the late medieval Renaissance period, the costumes were more like spots or splotches, like stains. Food stains, or moral stains. And there is a whole iconography that goes back to medieval times according to which solid colors are godly, and stains and splotches are diabolical.

Tom: Wow, so the eaters of leftovers were diabolical in some sense. Maybe that’s how leftovers got a bad name.

Janet: To go back to the Commedia dell’arte, the harlequin figure was somebody who could turn the world on its head. He started off as a valet at the beginning of the play, but might end up as a doctor or lawyer –or even the emperor– at the end.

Tom: Maybe the same rules apply to the food harlequins. You bring home this plate, you serve this plate to people, they’re impressed and you got it for cheap.

Janet: Yes, yes, or even without that, you fantasize. You eat this stuff, and you’re a god.

***

Janet Beizer is a Professor of Romances Languages and Literatures at Harvard University. Her new book in progress is entitled: The Harlequin Eaters: The Patchwork Imaginary of Nineteenth-Century Paris.

March 9, 2016

Our Genetic Dark Matter

By Sarah Alger

Our museum here at Massachusetts General Hospital is one not just about medical history, but also about modern-day innovation, and by extension, researchers grappling with today’s biomedical mysteries. One such mystery has to do with our fundamental understanding of genetics (I hope you’ll forgive the slight deviation).

Upon the first publication of the human genome in 2000, we learned that we have only about 20,000 genes (many fewer than scientists had anticipated); moreover, genes make up a mere 1.5% of the genome.

How can this be? What’s in the genome if not genes?

As we learned in high school biology, DNA prompts the creation of a complementary strand, called RNA, which does DNA’s bidding (making proteins). Yet this only happens with our 1.5% of the genome. With the remaining 98.5%, many of these mysterious pieces of DNA do generate RNA, but they don’t go on to create proteins.

For a long time these swaths of the genome were dismissed as “junk.” However, researchers at Mass General and elsewhere are beginning to find that at least some expanses–called long noncoding RNA–have effects on human development and disease. Jeannie Lee, a molecular biologist at Mass General, found that it was a long noncoding RNA that is responsible for “silencing” one of a female’s two X chromosomes (were both to be active, genetic problems would arise). Other work has uncovered the importance of these RNA strands to the refinement of a fetus’s features.

For a long time these swaths of the genome were dismissed as “junk.” However, researchers at Mass General and elsewhere are beginning to find that at least some expanses–called long noncoding RNA–have effects on human development and disease. Jeannie Lee, a molecular biologist at Mass General, found that it was a long noncoding RNA that is responsible for “silencing” one of a female’s two X chromosomes (were both to be active, genetic problems would arise). Other work has uncovered the importance of these RNA strands to the refinement of a fetus’s features.

It is still unknown how much of these strands serve vital functions. Dubbed by some scientists “dark matter,” referring to unseen matter in the universe, much of it remains a mystery.

Our exhibit, drawn from Mass General’s Proto magazine (full story here), underscores just how rich but young the history of genetics is. At Mass General, a genetics unit was established in the early 1960s (largely for diagnosis, rather than fundamental findings), and the draft publication of the genome was just 16 years ago.

March 7, 2016

Plato and the Amazons

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

What did Plato have to say about Amazons? The great philosopher might seem an unlikely commentator on the fierce, barbarian warrior women. How could Amazons or warlike females figure in the great thinker’s rigorous dialectical dialogues on politics, justice, love, virtue, education, metaphysics, and laws?

In fact, there is evidence that Plato (b. 428 or 424 BC) devoted some thought to women’s roles in ideal states. Published after his death in 348 BC, Plato’s Laws features a remarkably admiring perspective on Amazons and their real-life counterparts, the horsewomen archers of the steppe tribes around the Black Sea. In the Laws dialogue, an Athenian, a Spartan, and a Cretan debate the best ways to raise citizens in an ideal state well prepared for both peace and war.

Plato’s Athenian suggests that at age six, boys “should have lessons in horse riding, archery, javelin-throwing, and slinging–and the girls, too, may attend the lessons, especially in the use of the weapons.” Notably, these activities are not the military skills of Greek hoplite warriors. Instead, these skills mimic the expertise of mounted nomad archers of Scythia-Sarmatia, the territory stretching from the Black Sea to Mongolia. By Plato’s time, Scythia was notorious for warlike women who rode to battle alongside the men. Plato and his readers would have been familiar with vivid descriptions of Scytho-Sarmatians’ customs by Herodotus (484-425 BC).

In his surprising proposal that Greeks should take up a Scythian lifestyle, Plato specifies that foreigner teachers would be imported to instruct the children to ride and shoot arrows in wide-open spaces created for the purpose. (Laws 7.794c-795d)

It is fitting, says Plato, that “girls must be trained in precisely the same way as the boys” in athletics, riding horses, and wielding weapons. In an emergency, then, women “tough enough to imitate Sarmatian women” could “take up bows and arrows like Amazons, and join the men” in battle against enemies. This radical departure from traditional Greek gender roles is not only justified by the ancient stories of Amazons. Plato declares that we “now know for certain that there are countless numbers of women . . . around the Black Sea who ride horses and use the bow and other weapons” just like the men. In their culture, he notes, “men and women have an equal duty to cultivate these skills.” Together, the men and women pursue “a common purpose and throw all their energies into the same activities.”

Plato argues that these sorts of mutual cooperation and equal training are essential to a society’s success. Indeed, any state that does otherwise is “stupid,” because without women’s participation “a state develops only half its potential” when at the same cost and effort it could “double its achievement.” Plato likens this all-inclusive, egalitarian approach to the famous Scythian ability to shoot arrows with either the right or left hand. Such ambidexterity is crucial in fighting with bows and spears, and “every boy and girl should grow up versatile in the use of both hands.”

The example of Scythian women, says Plato, proves that it is possible and advantageous for a state to decide that “in education and everything else, females should be on the same footing as males and follow the same way of life as the men.” Indeed, it would be a “staggering blunder” for a society to “deny women this kind of partnership with men.” (Laws 7.804c-806c)

About the author: A research scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014) and The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 1, 2016

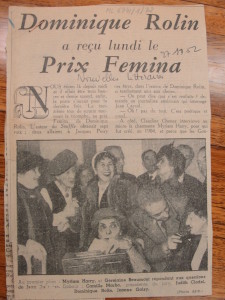

#PrizesSoMale? A Brief History of French Literary Awards

By Margot Irvine, Guest Contributor

Red carpets, sealed envelopes, statuettes, gowns and tuxedos… it’s the time of year when we tune in to the Grammys and Oscars to take in the spectacle surrounding these sought-after cultural awards. Prizes have been given out for the best plays and poems since antiquity but they began to proliferate and take the form we recognize today in the early years of the twentieth century. The Nobel Prize for Literature was established by Alfred Nobel’s will in 1895 and was awarded for the first time in 1901. In 1896, French writer Edmond Goncourt’s final testament envisaged a prize of a slightly different sort which would recognize the best book published within the year rather than a body of work. The prix Goncourt was to be selected by a jury of ten “men of letters”, “only men of letters, we will not have any great lords or politicians”. Not only was the jury made up exclusively of men, it quickly became clear that this prize would only ever go to men. Somewhat like the #OscarsSoWhite campaign today, other groups quickly realized that this meant that many potential winners were being overlooked; especially women who were publishing in greater numbers at this time and had begun to form their own literary communities and networks.

The jury for the 1978 Goncourt prize

New prizes are often created because of rivalries and exclusions and, in 1904, the prix Vie heureuse, a rival prize to the Goncourt, was awarded for the first time by a jury made up of only of women of letters.

Both prizes still exist, though the prix Vie heureuse was renamed the prix Femina in 1922. Like the red carpets, crisp envelopes and statuettes of the Oscars, particular rituals have developed around them. Since 1914, the prix Goncourt has been awarded at the Drouant restaurant. A history of the prize is given on the restaurant’s web site, the lunch offered to the jury is complimentary and the exterior of the building is decorated with the signatures of former members of the jury. The jury meets at the restaurant on the first Tuesday of every month and enjoys a meal that likely consists of the house specialties: foie gras with port, mullet in shallot and white wine sauce, or scallops in butter. The winners are given a symbolic check for 10 euros: the prestige of the award and the greatly increased sales that accompany it are the real prizes. Literary awards are traditionally announced in November in France and the Goncourt and Femina prizes have an agreement whereby the privilege of awarding the prize first alternates between them each year.

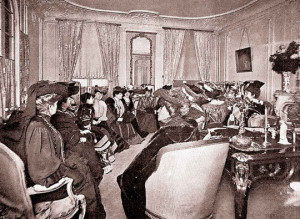

The first meeting of the Prix Femina at the home of Anna de Noailles

By examining the correspondence exchanged between the members of the prix Femina jury, we can tell that, until the Second World War, most if not all of their regular meetings occurred in the private homes of jury members over lunches, dinners and teas. Unlike male authors, women writers had no tradition of meeting in the public spaces of cafés, restaurants and artists’ studios in the early years of the twentieth century. The spaces of women’s literary sociability in these years reflect their still marginal status and continuing association with the private sphere. Femina jury member Camille Marbo’s memoirs, À travers deux siècles, souvenirs et rencontres (1883-1967), are instructive about the gradual professionalization of this women’s literary community in the post-war years, symbolized by a change in the places they favoured for their meetings. Marbo writes that, after she became a member of the jury in 1944, the jurors gradually went from meeting in private homes to gathering for teas and lunches at the Ritz until, eventually, they held their deliberations in a neutral boardroom. In recent years, the jury has announced their winner after lunches at the posh Hotel Crillon or the Cercle Interallié.

In a letter from 1956, jury member Madeleine Saint-René Taillandier jokingly complains that she and fellow jury members don’t get much in exchange for their tireless hours of reading in order to determine which book is the best, besides tired eyes and lobster for lunch. What they did get, though, was an opportunity to meet, form networks, have lively discussions, and judge books, beginning at a time when women didn’t yet have the right to vote.

The 2011 Femina jury.

So, when you are discussing the Oscars around the water cooler at work, remember that cultural prizes have been occasions to celebrate, gossip, disagree, exclude and include for a long time.

Margot Irvine is Associate Professor of French and European Studies at the University of Guelph. Author of Pour suivre un époux: Les récits de voyages des couples au XIXème siècle français (Nota Bene, 2008), she is currently preparing an edition of correspondence exchanged by the members of the jury of the prix Femina (1904-1964).

Further Reading:

For more on the history of French literary prizes, see Sylvie Ducas, La Littérature à quel(s) prix? Histoire des prix littéraires, Paris, La Découverte, 2013.

For analysis of the place of prizes in the cultural industry today, see James F. English, The Economy of Prestige : Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value, Cambridge, Mass, Harvard UP, 2005.

For more on the history of the prix Femina, see Margot Irvine. “« Des liens de confraternité? »: Friendships and Factions on the Jury of the Prix Femina (1904-1964)” in Solidaires, Solitaires, eds. Elise Hugueney-Leger and Caroline Verdier, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. 137-150.

Bric-a-brac-o-mania is a monthly column  on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.

on nineteenth-century literary, visual, and material culture edited by Rachel Mesch.

“[…] rien qu’hommes de lettres, on n’y recevra ni grands seigneurs, ni hommes politiques”, Edmond de Goncourt`s will, reproduced in Jacques Robichon, Le Défi des Goncourt, Paris, Denoël, 1975, 333.

Camille Marbo, À travers deux siècles, souvenirs et rencontres (1883-1967), Paris, Grasset, 1967, 315-316.

« Heureusement que nous avons fait deux heureux au Femina — l’éditeur et l’auteur — car pour ce que nous récoltons nous-même du Prix Femina ce n’est pas lourd… sauf le homard et les yeux fatigués! » (letter from Madeleine Saint-René Taillandier to Judith Cladel, 13 january 1956, fonds Cladel, Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington).

February 24, 2016

Museum Mysteries: Butterscotch, Fish Juice and Castaways

by Sarah Alger

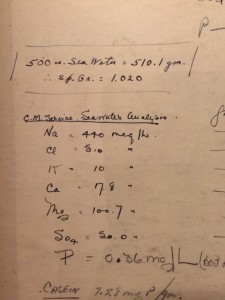

Sea water analysis from the MGH laboratory notebook.

In Massachusetts General Hospital’s collection is a laboratory notebook that details experiments conducted in 1944 and 1945. Tidy tables and neat handwriting show data gathered from a handful of research subjects: their weight, urine and stool output, blood analysis, and their intake of fresh water–and, curiously, sea water.

These subjects, all male, were conscientious objectors during World War II. Sent to Massachusetts General Hospital for duty, they underwent unusual experiments aimed at improving the life span of military men who found themselves adrift in life rafts.

Mass General’s Allan Macy Butler, chief of the hospital’s pediatric service, was charged by the Office of Scientific Research and Development to find ways to delay dehydration and improve military lifeboat rations, in collaboration with fellow pediatrician James Gamble.

In this particular experiment, subjects endured a starvation diet for a week and consumed a combination of fresh and sea water. Coleridge’s “Water, water, everywhere…nor any drop to drink” did not prove entirely true: A combination of one part sea water to three parts fresh appeared to be acceptable.

In a separate experiment, Butler found that “prolonged mechanical squeezing of 1 kilo of fresh sea bass” yielded fluid that was unsuitable and too scant for “the thirsting castaway.” In another, butterscotch or caramel candy appeared to slow the effects of dehydration.

Yet another experiment sent five subjects into Cotuit Bay off Cape Cod on a 14-foot-square raft to measure the effects of temperature, breeze and shade on their hydration. As Butler observed, “The circumstance of greatest hazard to castaways is absence of breeze.” Constantly wetting one’s clothes was advised for “keeping cool to a point beyond bodily pleasure but not across the margin of chilliness; a somewhat difficult precept.”

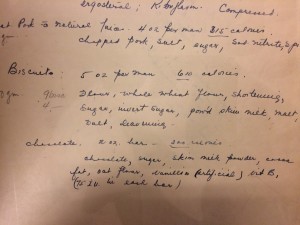

From the MGH laboratory notebook: ingredients in the dastardly biscuits.

Physiological effects of typical life raft rations (malted milk tablets, biscuits, pork and chocolate) was the subject of another weeklong experiment–and offered a glimpse of the personalities of these stand-in castaways. Said one subject to researchers: “The biscuits tasted like compressed sawdust and if I were on a life raft I believe that I would have fed them to the fishes.” Remarked another: “The biscuits were all right during the first couple of days…Later on, of course, they were high and holy hell to get down…Around the fifth day I began to cherish deep and irreconcilable loathing for fasting in general and Navy rations in particular.”

February 23, 2016

Star Struck: Catherine de Médicis and the Science of Superstition

By Sophie Perinot (Guest Contributor)

In 1572 work on a palace under construction for Catherine de Médicis, Queen Mother of France, was called to an abrupt halt. The project, eventually completed as the Palace des Tuileries, was eight-years and millions of écus underway when one of Catherine’s astrologers predicted that the Queen would die “near St Germain.” As the worksite was part of the diocese of St Germain l’auxerrois, Catherine was determined to take no chances. Her partially completed palace was abandoned, and she ordered construction of what became the Hôtel de Soissons into which she subsequently moved.

In 1572 work on a palace under construction for Catherine de Médicis, Queen Mother of France, was called to an abrupt halt. The project, eventually completed as the Palace des Tuileries, was eight-years and millions of écus underway when one of Catherine’s astrologers predicted that the Queen would die “near St Germain.” As the worksite was part of the diocese of St Germain l’auxerrois, Catherine was determined to take no chances. Her partially completed palace was abandoned, and she ordered construction of what became the Hôtel de Soissons into which she subsequently moved.

Today we would doubtless view Catherine’s astrology-based decision as rooted in

superstition. But in the 16th century astrology was widely considered a respectable science, and it mingled freely with its close cousin astronomy:

“. . . astrology was a part of every man’s picture of the cosmos, the educated even more so than the uneducated. Astrology was used in nearly every facet of life, from tracing lost articles and determining the nature of diseases to plotting the course of nations.”

There were a variety of specializations within the field of astrology, from the very respectable basics of using heavenly observations to make general predictions about the weather, finances, etc., to the more controversial practice of casting a chart based on the moment a question was posed and then providing an answer according to celestial aspects. And Catherine was hardly the only monarch employing astrology or astrologers in decision-making. The severe and devout Philip II of Spain consulted them, even upon the creation of his tomb. And who has not heard of John Dee in connection with England’s Elizabeth I? It was not until the opening years of the 17th century, with the proliferation of the telescope and overthrow of the earth-centered universe, that astrology began to seriously lose followers.

So, rather than making her seem foolish, Catherine’s fascination with the observable movements of the heavens and her belief that they influenced human fate would have reinforced her image as a woman of science. This was a reputation she enjoyed from the moment she set foot in France as the bride-to-be of the then Dauphin, when her pronounced interest in geography, physics and astronomy set her apart from the court’s other ladies. Although Catherine may not be remembered for her scientific bent now, during her lifetime she was clearly celebrated for it by her contemporaries, including the poet Ronsard.

The astrologer who made the palace-stopping prediction had arrived in France as part of Catherine’s entourage. His name was Cosimo Ruggieri, and he was descended from a family long patronized and protected by the Medici in Florence for their astrological talents. Ruggieri was not Catherine’s only astrologer—her name is often linked with that of Nostradamus, and there were certainly others. Such was Catherine’s mania for the movements of and messages in the stars, that in addition to employing professionals she personally studied astronomy and astrology.

As part of that study she owned a number of books with bronze or brass pages full of revolving disks and tools to help her analyze her celestial observations. By their description, these were likely astronomical compendiums, like the one illustrated at left (part of the collection at Florence’s Museo Galileo, which I credit for the photo). Compendiums were works of art with scientific purposes. The owner of a well-equipped astronomical compendium would be able to make purely scientific calculations—like the expected time of a sunrise or sunset—while simultaneously having volvelles at hand specifically designed to aid in astrologically prognostications.

As part of that study she owned a number of books with bronze or brass pages full of revolving disks and tools to help her analyze her celestial observations. By their description, these were likely astronomical compendiums, like the one illustrated at left (part of the collection at Florence’s Museo Galileo, which I credit for the photo). Compendiums were works of art with scientific purposes. The owner of a well-equipped astronomical compendium would be able to make purely scientific calculations—like the expected time of a sunrise or sunset—while simultaneously having volvelles at hand specifically designed to aid in astrologically prognostications.

So next time you read a judgmental description of Catherine as a practitioner of the “dark arts,” bear in mind that astrology would not have fallen within that category at the time the Queen was alive. Prognosticating based on the stars in the heavens would have been considered science not superstition.

Lawrence E. Jerome. “Astrology and Modern Science: A Critical Analysis. Leonardo

Vol. 6, No. 2 (Spring, 1973), pp. 121-130

Ibid.

It is worth noting that even in the 17th century astrology continued to cling tenaciously to its cultural perch. Thus, even as Galileo was being sanctioned by the Pope for his purely scientific assertion of a heliocentric universe, that same Pope was secretly practicing astrology which his church on his authority prohibited. (Mormando, Franco. Bernini: His Life and His Rome. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.) And shortly before his death in 1630 the great Kepler drew up horoscopes as a means of supporting himself declaring, “Mother Astronomy would certainly have to suffer if the daughter Astrology did not earn the bread.” (Bart J. Bok and Margaret W. Mayall . “Scientists Look at Astrology.” The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Mar., 1941), pp. 233-244.)

Arguably Catherine deserves greater recognition than she receives for bringing science to the court of France and employing it to aid the state. Wellman, Kathleen. Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. Yale University Press, 2013

Sophie Perinot is the author of several works of historical fiction, including the recent novel, Médicis Daughter which tells the story of the 16th century French Valois court through the eyes of Catherine de Médicis’ youngest daughter, Margot. When Sophie is not visiting corners of the past, she lives in Great Falls, Virginia, with her three children, two cats, one dog and one husband.

February 22, 2016

What Civil War Nurses Did After the War

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Civil War nurse Cornelia Hancock

The Civil War was a pivotal experience for many of the women who served as nurses, whether they served for three weeks or three years. For many it was their first time away from family and home, and their first step outside the narrow framework of what society expected from them. They learned not only new skills but also new confidence. Whether in the immediacy of letters at the time or with the distance of memory, they expressed deep satisfaction with the work and the way of life, though they often groused about a particular detail. Katharine Prescott Wormeley, who served first on the hospital transport ships and later as the matron for a hospital for convalescent soldiers in Rhode Island, claimed to speak for the army nurses as a whole: “We all know in our hearts that it is thorough enjoyment to be here,—it is life, in short; and we wouldn’t be anywhere else for anything in the world.” Emily Parsons, who served as a nurse for two years at a variety of hospitals despite being blind in one eye, partially deaf, and lame, took the sentiment one step further: “I should like to live so all the rest of my life.”

Parsons, like most of the women, and the soldiers they cared for, went home at the war’s end. Nursing had been a temporary part of their lives, just like being a soldier was a temporary part of the lives of most of the men who served in the war. Many stepped back into their old lives as daughters, seamstresses, schoolteachers, and wives. Others created lives that were a little bigger than they had been before the war.

Some made a living writing. The most famous of these was Louisa May Alcott, whose account of her Civil War experience, Hospital Sketches, was the first work she published under her own name.

A few women who served as nurses during the war went on to earn medical degrees. Vesta Swarts, for instance, was a high school principal in Auburn, Indiana, before the war. She nursed at Louisville, Kentucky, from sometime in 1864 until March 1865, when she was honorably discharged, a fact she mentions with pride in an essay she wrote on her war work. After the war, she became a physician–a challenging proposition for women–and returned to Auburn, where she practiced medicine with her husband for the next thirty years.

Many of the middle-class women who volunteered as nurses were part of the large and varied community of American reformers before the war. Their wealthier counterparts often came from families who expected them to take part in high-profile charity work. After the war, both middle-class reformers and wealthy philanthropists used their newfound experience at organizing, political activism, and manipulating their way through male-dominated bureaucracies to expand their influence. Some took on new leadership roles at the local level. Parsons, for instance, organized a campaign to open a charity hospital for women and children in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. A few used their experience as a springboard to national leadership roles, founding groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union, the American Social Science Association, and the American Red Cross. They involved themselves in opening schools, reforming prisons and asylums, improving conditions for women and children, “saving” unmarried mothers and their children (both in moral and practical terms), and providing vocational training for girls. Some became active in the labor, women’s rights, and temperance movements, which expanded after the war to fill the political and emotional space previously occupied by abolition. Others spearheaded social welfare programs designed to alleviate the human misery left by the war. They formed relief funds for war widows and orphans, and programs to settle unemployed veterans on farmland in the West, and schools for former slaves. Cornelia Hancock, for instance helped found a freedman’s school in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, where she taught ex-slaves for a decade. (Not as innocuous as it sounds. At one point those who objected to the concept of education for black children riddled the schoolhouse with fifty bullets.) Several decades after the war, they used those same skills to advocate for themselves. Arguing that they too had served their country, they successfully pushed through the Union Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892, which provided government pensions for army nurses similar to those given to Union soldiers.

The one thing few of them did was work as nurses.

But if they didn’t continue to work as nurses after the war, their collective experience in the war had convinced Americans that nursing was not only a respectable job for a woman but that it could be a skilled profession.

In 1868, the American Medical Association recommended that general hospitals open schools to train nurses. It was a two- edged response to the success of volunteer nurses in the Civil War. The AMA both acknowledged the value of skilled nursing in hospitals and hoped to avoid another flood of untrained and uncontrollable volunteer nurses in future wars. By 1880, there were a total of 15 nursing schools in the United States; by 1900, there were 432. Nursing had become recognized as a skilled profession.

Clara Barton with a graduating class of nurses, 1903

We have several copies of The Heroines of Mercy Street to give away. Sign up below before 11:00 PM Eastern Standard Time on February 29 for a chance to win.

February 16, 2016

The Short and Wondrous Career of Harry Glicken

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

When I knew Harry Glicken during the mid-1970s at Venice High School in Los Angeles, I could not imagine my classmate as a history-maker of the future. He was disheveled, wore unstylish clothing over his gaunt frame, and had trouble keeping his glasses straight. He spoke in a rush and loved to argue. But to anyone paying attention, which I wasn’t, there was more to Harry than his appearance let on.

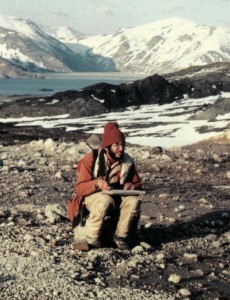

Harry Glicken in the field, 1980s

Harry was wickedly smart, a true brainiac in a school with quite a few bright kids. He had an off-balance sense of humor, often spiking his jokes with time-release punch lines that took a while to ignite. Harry loved science, and in its interest he could behave with unpredictable enthusiasm: he once brought in fresh human semen to biology lab. That was a delightfully awkward moment.

After Harry and I parted ways to go to college, I assumed he’d end up in the sciences and that he’d not likely again come to my attention. I was right on one count and wrong on the other.

Around 1993, I was astonished to hear from a friend that Harry, by this time a volcanologist, had been killed while studying the eruption of Mount Unzen in Japan. I then found out that he had narrowly avoided death eleven years earlier during the eruption of Mount St. Helens. That’s when I realized that I had not really known Harry Glicken at all.

I caught up on his career. Harry earned his undergraduate degree at Stanford University and went on to graduate school at the University of California-Santa Barbara. As a Ph.D. student in the spring of 1980, he began working for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to help keep an eye on the volatile situation at Mount St. Helens in Washington. Harry was the sole person manning the Coldwater II observation post just north of the volcano throughout much of May. But he he had to leave on May 17 to meet with his faculty advisor. His mentor and USGS supervisor, David Johnston, then temporarily took Harry’s place at Coldwater II.

The next day, Harry heard the news that an earthquake at 8:32 a.m. had triggered an avalanche and an enormous explosion of rocks, hot ash, and molten lava at Mount St. Helens. Coldwater II was obliterated within minutes, and Johnston’s body was never found. Harry, however, did not yet know his friend’s fate, and he found a helicopter pilot willing to take a look. Thick clouds of ash kept the pilot from getting as close to Coldwater II as Harry wanted, so he found another pilot willing to give it a try.

The eruption of Mount St. Helens, May 18, 1980

Everything on the ground was desolate. “One wouldn’t know a forest existed here,” Harry wrote. The destruction deeply shook him; he had seen burned people and a dead elk, covered with ashes but still standing. In addition, Harry felt responsible for Johnston’s death. He threw himself into contributing to the USGS survey of the avalanche and became an expert on volcanic debris avalanches.

Harry recovered from the loss of his friend and in 1990 travelled to Japan as a visiting postdoctoral fellow at Tokyo Metropolitan University. Within months, he was close to the scene of yet another eruption, on the island of Kyushu at Mount Unzen, a volcano that had been dormant since 1792. He, along with the French volcanology and photography team of Katia and Maurice Krafft and a group of journalists, was observing the volcano at 4 p.m. on June 3, 1991, when a gigantic explosion collapsed the volcano’s lava dome, started a flow of molten rock, and launched a high-temperature cloud of ash that engulfed the observers. Harry, 33, and his colleagues died instantly along with 39 other people.

Harry and David Johnston are still the only American volcano scientists ever to die during volcanic eruptions. I wish they had no such distinction. If things had somehow gone differently, I would enjoy hearing my rumpled and eccentric classmate, glasses askew, rush through the story of how he survived.

Further reading:

Fisher, Richard Virgil. Out of the Crater: Chronicles of a Volcanologist. Princeton University Press, 2000.

Glicken, Harry. “Rockslide-debris avalanche of May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens volcano, Washington.” U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Open File Report 96-667, 1996.

Lopes, Rosaly M.C. The Volcano Adventure Guide. Cambridge University Press, 2005.