Holly Tucker's Blog, page 20

January 4, 2016

A Roman Army’s Vulture Mascots: First Banded Birds

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Vultures were often the first responders to the carnage of war. The great birds of prey could be seen wheeling over battlefields to feast on the dead and dying. Scavenging vultures learned to follow ancient armies on the march in anticipation of a banquet of carcasses.

When the famous Roman commander Marius (157-86 BC) was leading campaigns against the Germanic tribes (the Cimbri, Teutones, Ambrones) in Europe, two vultures made a habit of hovering over his armies as they marched to victories.

One day, the troop’s blacksmith forged two bronze collars and the soldiers managed to capture the pair of vultures with nets. The men placed the metal bands around their necks and released their new mascots. Ever after, whenever the soldiers spotted the birds and saw the collars flashing in the sun, their spirits were raised and they would cheer their soaring escorts. Vultures had been good omens since the founding of Rome. The vulture pair boosted the army’s morale–they were taken as an omen that the Romans would be victorious and that their vulture escorts would soon feed on the corpses of the enemy.

This anecdote describing the earliest documented bird banding was first reported by the zoological historian Alexander of Myndus and cited by Plutarch in his Life of Marius.

European vultures are solitary or in pairs; they are very intelligent, monogamous, and mate for life as equal companions. The vultures banded by Marius’s men were probably a male and female. Vultures can live 40 years; the wingspans range from 7 to 10 feet. The birds were not described as tame pets, but it is easy to imagine the Roman soldiers setting out food near camp or while on the march to seal a bond between the army and the raptors. There were several species of vultures in Europe during the Roman period: possibilities include griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus); cinereous or black vulture (Aegypius monachus), bearded vulture or lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus).

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” nonfiction finalist for the National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014), shortlisted for the London Hellenic Prize.

December 24, 2015

Christmas in the Trenches

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

“Little father outside in slaughter and fight surely thinks of us on Christmas night”

Contrary to the confident predictions of August 1914, the war was not over by Christmas. The killing would persist through Christmas 1914—the famous “Christmas Day Truce” on one battlefield in Belgium notwithstanding—and for another three Christmases, before the armistice brought the conflict to an end in November 1918.

The Baden-Württemberg “Haus der Geschichte” (History House) in Stuttgart is currently hosting a wonderful special exhibition on “Das Friedensfest in Kriegszeiten” (The Festival of Peace in Times of War), to accompany its larger exhibition, “Fastnacht der Hölle” (Carnival of Hell), on the First World War and the senses. The special exhibition, which runs until January 11, 2015, is presented in the form of an advent calendar, with 24 display boxes arranged in rows, each showcasing a different artifact or document relating to Christmas and the First World War in the Baden and Württemberg armies. It is also broadly chronological and emphasizes the increasing tensions and fatigue as the war progressed. The sentimental postcards produced for Christmas 1914, depicting divided but optimistic families, already struck a naïve note a year later.

One of the most touching displays (#3) contains a child’s drawing of Christmas trees, peppered with shrapnel holes. The drawing belonged to Reserve Lieutenant Karl August Zwiffelhoffer, who received an “unexpected Christmas vacation” in November 1916 in order to attend his uncle’s funeral. He took this picture, drawn by his four-year-old daughter, Annie, back to the front with him. It was folded in the breast pocket of his jacket when he was killed by shrapnel on May 4, 2017, in the bloody ‘Chemin des Dames’ offensive. Although his effects were returned to his widow, she could not bring herself to open the box in which they were delivered, and the uniform jacket and its contents were not discovered until Annie moved to an old people’s home decades later and her daughter went through her belongings.

Other display cases contain: orders of service from battlefield worship; children’s Christmas wish lists, requesting cigars (presumably to send to the troops); Christmas postcard advertisements for Bahlsen cookies; a haunting acquatint etching of a Stuttgart soup kitchen at Christmas by the artist Reinhold Nägele; Steiff soldier dolls; home-drawn Christmas cards, depicting life on the home front; and military Christmas ornaments, like this Zeppelin Christmas tree decoration.

Other display cases contain: orders of service from battlefield worship; children’s Christmas wish lists, requesting cigars (presumably to send to the troops); Christmas postcard advertisements for Bahlsen cookies; a haunting acquatint etching of a Stuttgart soup kitchen at Christmas by the artist Reinhold Nägele; Steiff soldier dolls; home-drawn Christmas cards, depicting life on the home front; and military Christmas ornaments, like this Zeppelin Christmas tree decoration.

Additional Resources:

A brief video of the special exhibit by local region tv is available on their website (commentary in German): http://www.regio-tv.de/video/343043.html

There is a slide-show of selected artifacts on the SWR website:

For more information on visiting the exhibition (open Tuesday-Sunday, until January 11, 2015), see: http://www.krieg-und-sinne.de/besucher/

Entry to the exhibition (including the special Christmas side-exhibit described here) costs 3 Euros for adults, and the Haus der Geschichte is walking distance from the main Stuttgart train station. The special exhibition alone is worth the walk and the entrance fee.

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in December 2014.

December 21, 2015

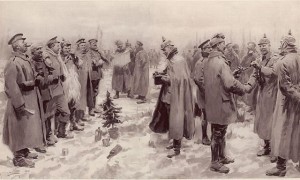

The Christmas Truce of 1914

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

My usual role at Wonders and Marvels is writing about the non-Western world, with an occasional side-step into imperialism and related topics. The next topic on my Big List of Blog Posts was the suppression of thuggee in nineteenth century India. Somehow that didn’t seem appropriate this week. Instead I offer you one of my favorite historical Christmas stories:

For most of us, the most vivid images of World War I are the trenches on the Western front. Men dug into positions on either side of a no-man’s land of craters and burned out buildings. Barbed wire and sandbags provided little protection from enemy shelling or snipers; they provided no protection from rats, lice, flooding, or the dreaded “trench foot”. The battlefields were noxious with the smell of rotting corpses, overflowing latrines and poison gas fumes.

Trench warfare was hell. It also made possible one of the most extraordinary events of the war: the unofficial Christmas armistice of 1914. The truce began when some German troops decorated their trenches with candles and Christmas trees and sang carols. British troops responded with carols of their own. On Christmas Day, some groups ventured into “no-man’s land” to share food, sing carols, hold joint services for their dead and play soccer matches.

One German soldier, Josef Wenzel, described the scene in a letter to his parents:

One Englishman was playing on the harmonica of a German lad, some were dancing, while others were proud as peacocks to wear German helmets on their heads. The British burst into a song with a carol, to which we replied with “Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht. It was a very moving moment–hated and embittered enemies were singing carols around the Christmas tree. All my life I will never forget that sight.

It is estimated that 100,000 men took part in the Christmas truce. In some places, the truce lasted only through Christmas day. In others, it lasted until New Year’s Day. In some sectors, the war continued unabated.

The Christmas truce did not recur in 1915. Both the British and the German high commands were appalled at the blatant fraternization with the enemy and gave strict orders against future incidents. After all, how do you fight a war if the men at the front decide not to fight?

Peace on earth, good will to men.

Conflict, Captivity, and Piracy in the Early United States

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor) and Arthur Goldsmith (Guest Contributor)

Following its War of Independence, the United States’ first international armed conflict was in North Africa. The security issue was interference with U.S. merchant shipping from pirates or corsairs who operated out of ports in the Barbary states. With tacit or explicit local political backing, the pirates seized cargo and captured crews and passengers, who could be held hostage or sold in the Ottoman slave market.

The threat was not new, but American commercial vessels in the Mediterranean had seldom been bothered due to treaties negotiated by the Crown and enforced by the Royal Navy. After 1783, however, any ship flying the Stars and Stripes was at risk. In that year alone, eleven U.S. commercial vessels were taken. The young democracy tried to arrange its own pacts with local Arab rulers, but these agreements proved unstable and subject to escalating demands from the other side.

With diplomacy seemingly going nowhere, recently elected President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 dispatched warships to the region to blockade strategic points along the North African coast and strengthen his bargaining position. A crisis occurred in 1803 when a U.S. man-of-war ran aground near Tripoli and its crew was imprisoned. A daring raid by American forces destroyed the frigate before it could be refitted by the pirates for their use. Combat operations ended with the Treaty of Tripoli in 1805, which secured the release of all remaining hostages and guaranteed free passage for American ships. But hostilities broke out again a decade later. The regional threat of piracy was not fully eliminated until France’s annexation of Algeria in 1834.

With diplomacy seemingly going nowhere, recently elected President Thomas Jefferson in 1801 dispatched warships to the region to blockade strategic points along the North African coast and strengthen his bargaining position. A crisis occurred in 1803 when a U.S. man-of-war ran aground near Tripoli and its crew was imprisoned. A daring raid by American forces destroyed the frigate before it could be refitted by the pirates for their use. Combat operations ended with the Treaty of Tripoli in 1805, which secured the release of all remaining hostages and guaranteed free passage for American ships. But hostilities broke out again a decade later. The regional threat of piracy was not fully eliminated until France’s annexation of Algeria in 1834.

Given the context, it is not surprising that Barbary captivity narratives had wide readership in early nineteenth-century America. There was already a large European literature on this topic, but two notable titles with American protagonists were History of the Captivity and Sufferings of Mrs. Maria Martin (1806), and The Captives, Eleven Years a Prisoner in Algiers (1899), a first-person account by James Leander Cathcart. Although the second book was published posthumously, the story was well-known at the time of the events. Barbary captivity narratives such as these both reflected and contributed to the political climate backing military intervention in North Africa. But were they true?

Given the context, it is not surprising that Barbary captivity narratives had wide readership in early nineteenth-century America. There was already a large European literature on this topic, but two notable titles with American protagonists were History of the Captivity and Sufferings of Mrs. Maria Martin (1806), and The Captives, Eleven Years a Prisoner in Algiers (1899), a first-person account by James Leander Cathcart. Although the second book was published posthumously, the story was well-known at the time of the events. Barbary captivity narratives such as these both reflected and contributed to the political climate backing military intervention in North Africa. But were they true?

Maria Martin writes vividly of her ship’s capture near the Rock of Gibraltar in 1800. “The corsair came along side, and in less than three minutes, more than half her crew boarded us, sword in hand…The barbarians were no sooner on board, than they began their favorite work, cutting, maming [sic] and literally butchering, all that they found on deck.” She was later sold as a slave, chained, imprisoned, fed a diet of bread and water, and eventually ransomed. This harrowing adventure, however, appears to have been made-up and largely plagiarized from an earlier and equally suspect narrative about a kidnapped Italian woman, The Captivity and Sufferings of Mary Velnet (1804).

Similarly sensational is James Cathcart’s Algerian journal. A junior officer, he was captured on the high seas by Barbary pirates in 1785 and subsequently enslaved. While kept in harsh conditions, he had relatively light duty in the palace of the ruler of Algiers caring for exotic animals in the palace zoo. Bright and adept at languages, Cathcart worked his way up to become a clerk in the local marine service. With his earnings, Cathcart purchased several taverns as well as a local residence with servants. He helped to arrange a treaty for the release of his shipmates, and in 1796 was able to acquire a ship and sail back to the United States with several of his fellow ex-slaves.

This story sounds farfetched, but subsequent events suggest Cathcart may have had the talents needed to pull it off. He returned to North Africa as a special envoy in 1798. Four years later, he was appointed to the consulates in Tunis and Tripoli, where he participated in the negotiations to resolve the First Barbary War. Cathcart also served as Consul-General for the United States in Cádiz from 1807–17. He finished his career in the United States Treasury.

Arthur Goldsmith is Professor Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Boston. His current research interests are African politics, democratization, and international relations.

Additional reading: Paul Baepler, White Slaves, African Masters: An Anthology of American Barbary Captivity Narratives. (University of Chicago Press, 1999); Khalid Bekkaou, White Women Captives in North Africa: Narratives of Enslavement, 1735-1830 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

December 15, 2015

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., Inhales Ether and Experiences a Cosmic Revelation

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., was an American physician of the nineteenth century and a prolific man of letters whose namesake son went on to become a famed U.S. Supreme Court justice.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., in 1891

In his 1879 essay (originally a lecture) titled “Mechanism in Thought and Morals,” Holmes described what he called “certain exalted mental conditions” that could lead to profound thinking, or at least to the illusion of profound thought. He cited dreams of sleep in which the dreamer imagined ideas far better or more beautiful than could be consciously created. Samuel Johnson, for example, “dreamed that he had a contest of wit with an opponent, and got the worst of it: of course he furnished the wit for both,” Holmes observed.

In another instance that Holmes cited, the Italian composer Giuseppe Tartini dreamed that he heard the Devil playing supernaturally enchanting music on the violin, and Tartini wrote it down after he woke up. The music became Tartini’s “Devil’s Trill” Sonata in G Minor, now the composer’s most celebrated work.

Eager to experience some exalted mental conditions of his own, Holmes decided to inhale a full dose of ether (then commonly used as surgical anesthesia) “with the determination to put on record, at the earliest moment of regaining consciousness, the thought that I should find uppermost in my mind.”

He breathed the gas and fell into a drugged stupor. “The veil of eternity was lifted,” he remembered. “The one great truth which underlies all human experience, and is the key to all the mysteries that philosophy has sought in vain to solve, flashed upon me in a sudden revelation. Henceforth all was clear: a few words had lifted my intelligence to the level of the knowledge of the cherubim.”

When somewhat awake and able to move, Holmes dragged himself to a desk and scrawled on paper “the all-embracing truth still glimmering in my consciousness.” It was these words:

“A strong smell of turpentine prevails throughout.”

Later Holmes read the words with incredulity and speculated that the ether had briefly made him insane. What a letdown! There was no brilliance or genius here. As Holmes wrote, the experience cast into doubt “the value of our self-estimate, sleeping.”

Further Reading:

Holmes, Oliver Wendell Sr. “Mechanism in Thought and Morals.” 1879.

O’Toole, Garson. “Secret of the Universe: A Strong Smell of Turpentine Prevails Throughout.” The Quote Investigator blog, March 31, 2012.

December 14, 2015

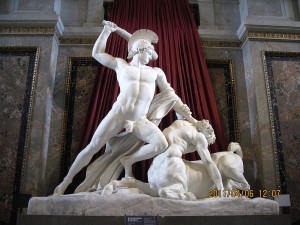

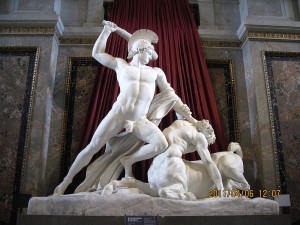

Can Centaurs Be Cuddly?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

My department’s blog this month features a Christmas special on gifts for classicists. I’ve been singled out as particularly weird because my choice was a teddytaur: a disturbing combination of teddy bear and horse. But I’ve been interested in mythical hybrids for a long time, and I reckon the teddytaur is a particularly satisfying example because the reassuring cuddliness of a soft toy may seem to sit painfully with the character traits of many centaurs in myth. And, as Lisa Maurice has recently reminded us, centaurs have long featured in children’s fantasy literature; to many children, they’re as familiar as a teddy bear.

It’s important to remember that there were different types of centaur in ancient myth, and most of them weren’t cuddly at all. Almost all were aligned with the bad side of humanity; the bestial side, which emerges after too much to drink. In another post on this site, Laura Auricchio pointed out that when the Marquis de Lafayette was depicted as a centaur, this was partly a way of saying he’d spent so long on his horse that the two had merged, but partly a way of showing him as a dangerous character.

It’s important to remember that there were different types of centaur in ancient myth, and most of them weren’t cuddly at all. Almost all were aligned with the bad side of humanity; the bestial side, which emerges after too much to drink. In another post on this site, Laura Auricchio pointed out that when the Marquis de Lafayette was depicted as a centaur, this was partly a way of saying he’d spent so long on his horse that the two had merged, but partly a way of showing him as a dangerous character.

In classical myth the Centauromachy, or Lapith Wedding (a label which, for Game of Thrones fans, will recall the infamous Red Wedding episode, which starts with what IMDb euphemistically calls ‘considerable tension between the two families’), happens when the Thessalian king Pirithous and his people, the Lapiths, celebrate his marriage to Hippodamia. The centaurs, invited to the party, don’t behave in a civilized way. One gets drunk and tries to abduct the bride, and the party degenerates into a riot. The hero Theseus, a friend of Pirithous, manages to drive off the centaurs. Why invite the centaurs in the first place? Because they’re family, related by blood to Pirithous. We’ve probably all been to weddings where existing family tensions got a little out of control under the influence of alcohol!

But there’s another side to centaurs. It’s not exactly cuddly, but it’s positive. In ancient Greek myth, a particular centaur called Chiron was associated not with violence, but with healing. He is supposed to have educated many of the Greek heroes, and he taught the use of medicine to Asklepios himself. Unlike the other centaurs, he was born immortal, and again unlike them, he is shown wearing human clothing.

Who’s the daddy?

Why were these centaurs so different? Well, part of it relates to their parentage. While the centaurs at the Lapith Wedding were descended from Ixion, after he attempted to rape Hera but instead landed on an unfortunate cloud which resembled this goddess, Chiron’s father was Chronos and his mother was a nymph who’d been having sex with him but was caught in the act by Chronos’s wife Rhea; Chronos turned himself into a stallion in the hope Rhea wouldn’t recognize him. However, in an even less benign version of the myth, the horse element comes from the nymph turning herself into a mare to avoid Chronos’s lusts. Other centaurs too are associated with rape; for example, Nessus, who tries to rape Herakles’ wife Deianeira.

My own favourite version of the centaurs – other than teddytaur – has to be the Xena Warrior Princess episode ‘Is there a doctor in the house?’. Here, Xena helps an Amazon married to a centaur – a great marriage, two anomalous figures of ancient myth united – to give birth, to a baby centaur. In a particularly fine mixture of anachronisms, both Hippocrates (5th c BC) and Galen (2nd c AD) work at the same healing shrine of the god Asklepios although, as Marquis Berrey has pointed out, Galen is on record as writing that centaurs were impossible.

Centaurs: dangerous reminders of the bestial side of the human race, or wiser than us because of their combination of two identities in one body? Two natures, with all the uncertainties of which is dominant, or a perfect merger which is a source of power? Other half-human, half-animal creatures of myth gain their power by bridging various divides. They are guardians of treasure, able to live in both land and sea, wardens at the boundary of life and death, sometimes seductive (think mermaids), sometimes repulsive (think harpies). Teddytaur’s cuddly but disturbing mix of the soft fur and friendly face of a favorite toy with the body – and hooves – of a horse just takes it all one step further. Is he the perfect guardian for a small child? Or is he a step too far?

More reading:

Helen King, ‘Half-Human Creatures’ in John Cherry (ed.), Mythical Beasts (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 138-167.

Lisa Maurice, ‘From Chiron to Foaly: The Centaur in Classical Mythology and Fantasy Literature’ in Lisa Maurice (ed.), The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 139-168.

Can centaurs be cuddly?

By Helen King (monthly contributor)

My department’s blog this month features a Christmas special on gifts for classicists. I’ve been singled out as particularly weird because my choice was a teddytaur: a disturbing combination of teddy bear and horse. But I’ve been interested in mythical hybrids for a long time, and I reckon the teddytaur is a particularly satisfying example because the reassuring cuddliness of a soft toy may seem to sit painfully with the character traits of many centaurs in myth. And, as Lisa Maurice has recently reminded us, centaurs have long featured in children’s fantasy literature; to many children, they’re as familiar as a teddy bear.

It’s important to remember that there were different types of centaur in ancient myth, and most of them weren’t cuddly at all. Almost all were aligned with the bad side of humanity; the bestial side, which emerges after too much to drink. In another post on this site, Laura Auricchio pointed out that when the Marquis de Lafayette was depicted as a centaur, this was partly a way of saying he’d spent so long on his horse that the two had merged, but partly a way of showing him as a dangerous character.

It’s important to remember that there were different types of centaur in ancient myth, and most of them weren’t cuddly at all. Almost all were aligned with the bad side of humanity; the bestial side, which emerges after too much to drink. In another post on this site, Laura Auricchio pointed out that when the Marquis de Lafayette was depicted as a centaur, this was partly a way of saying he’d spent so long on his horse that the two had merged, but partly a way of showing him as a dangerous character.

In classical myth the Centauromachy, or Lapith Wedding (a label which, for Game of Thrones fans, will recall the infamous Red Wedding episode, which starts with what IMDb euphemistically calls ‘considerable tension between the two families’), happens when the Thessalian king Pirithous and his people, the Lapiths, celebrate his marriage to Hippodamia. The centaurs, invited to the party, don’t behave in a civilized way. One gets drunk and tries to abduct the bride, and the party degenerates into a riot. The hero Theseus, a friend of Pirithous, manages to drive off the centaurs. Why invite the centaurs in the first place? Because they’re family, related by blood to Pirithous. We’ve probably all been to weddings where existing family tensions got a little out of control under the influence of alcohol!

But there’s another side to centaurs. It’s not exactly cuddly, but it’s positive. In ancient Greek myth, a particular centaur called Chiron was associated not with violence, but with healing. He is supposed to have educated many of the Greek heroes, and he taught the use of medicine to Asklepios himself. Unlike the other centaurs, he was born immortal, and again unlike them, he is shown wearing human clothing.

Who’s the daddy?

Why were these centaurs so different? Well, part of it relates to their parentage. While the centaurs at the Lapith Wedding were descended from Ixion, after he attempted to rape Hera but instead landed on an unfortunate cloud which resembled this goddess, Chiron’s father was Chronos and his mother was a nymph who’d been having sex with him but was caught in the act by Chronos’s wife Rhea; Chronos turned himself into a stallion in the hope Rhea wouldn’t recognize him. However, in an even less benign version of the myth, the horse element comes from the nymph turning herself into a mare to avoid Chronos’s lusts. Other centaurs too are associated with rape; for example, Nessus, who tries to rape Herakles’ wife Deianeira.

My own favourite version of the centaurs – other than teddytaur – has to be the Xena Warrior Princess episode ‘Is there a doctor in the house?’. Here, Xena helps an Amazon married to a centaur – a great marriage, two anomalous figures of ancient myth united – to give birth, to a baby centaur. In a particularly fine mixture of anachronisms, both Hippocrates (5th c BC) and Galen (2nd c AD) work at the same healing shrine of the god Asklepios although, as Marquis Berrey has pointed out, Galen is on record as writing that centaurs were impossible.

Centaurs: dangerous reminders of the bestial side of the human race, or wiser than us because of their combination of two identities in one body? Two natures, with all the uncertainties of which is dominant, or a perfect merger which is a source of power? Other half-human, half-animal creatures of myth gain their power by bridging various divides. They are guardians of treasure, able to live in both land and sea, wardens at the boundary of life and death, sometimes seductive (think mermaids), sometimes repulsive (think harpies). Teddytaur’s cuddly but disturbing mix of the soft fur and friendly face of a favorite toy with the body – and hooves – of a horse just takes it all one step further. Is he the perfect guardian for a small child? Or is he a step too far?

More reading:

Helen King, ‘Half-Human Creatures’ in John Cherry (ed.), Mythical Beasts (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 138-167.

Lisa Maurice, ‘From Chiron to Foaly: The Centaur in Classical Mythology and Fantasy Literature’ in Lisa Maurice (ed.), The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 139-168.

December 11, 2015

Sweet Calas in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans Streets

By Thomas Parker (regular contributor) and Ashley Rose Young (guest contributor)

If you passed by the French Market in nineteenth-century New Orleans, you would have heard street vendors calling out with musical voices, “Calas, belles calas, tout chaud!”

Calas were a popular Creole street food made from a batter of day-old rice, eggs, sugar, and wild yeast transformed into a deep-fried delicious pastry covered with powdered sugar and sometimes dusted with cinnamon and other aromatic spices. Calas were most often sold in the streets by either enslaved women or free women of color, advertising their wares with cries what were later qualified as “enchanting songs.”

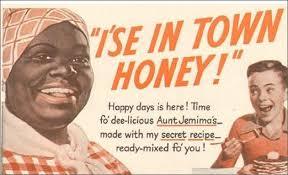

A “marchande des calas” (calas vendor) from an 1886 edition of Century Magazine

Preparation of the batter began days in advance, allowing natural yeasts to ferment and give the rice batter a slightly sour taste akin to the sourdough breads of Europe. Similar fermented flavors were popular in West Africa. Such dishes, as culinary historian Jessica B. Harris notes, include the buttermilk-like lar and tchiakri of Senegambia, which are allowed to ferment and take on a similarly sour taste.

Sundays were the largest food marketing days in New Orleans, a day that slaves normally had “free” in order to observe the Catholic Sabbath. Enslaved people, however, did not divest themselves of work on a day that was defined by rest and religious observation. Instead, they harvested fresh fruits and vegetables from their gardens or prepared foods to sell in the street in an attempt to make a little money. After attending to their spiritual lives in church, a diverse body of New Orleanians flocked to the city’s markets for a different, sweeter kind of solace.

The flavors and images of calas were as alluring as the sounds of the vendors cries were captivating. Indeed, the gustatory and visual imprint on the collective imagination of New Orleans’ market landscape in the nineteenth century were almost second in importance to the sound, and all of them together created an enticing mix of the familiar and exotic. Calas vendors reinforced images of comfort and tasty goodness. Yet, they were also widely construed as possessing a foreign, exotic (Créole), and sometimes sexualized voice.

The call of calas vendors, as described in travel narratives, novels, and folklore compendiums, came to symbolize all that was foreign (e.g. not American) about New Orleans. Black women’s voices were therefore part of a set of sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures employed primarily by white male authors to cast New Orleans as distinctly different from other American port cities and their food cultures.

Calas have today disappeared from the New Orleans streets, but were a part of the NOLA landscape well into the twentieth century, playing an important role in the city’s food history, as well as its history of social justice.

The revenues from the calas allowed women to support their families, and sometimes buy freedom, but also led to their marginalization. By bringing sweetness to whites, the women became associated with images of the black mammy figure, a woman who tirelessly cared for the children of white families in the old South. Seemingly innocuous, the stereotypical images of smiling black women—not unlike the Aunt Jemima that would later be used to sell maple syrup—erased the intense labor and the incredible culinary ingenuity demonstrated by New Orleans’ African and African American food entrepreneurs.

One might say that the road to freedom through calas sales came at a price. As women worked to liberate themselves and their family members through the sale of calas, successive generations of clients nostalgic for olden times reinforced a two-dimensional stereotypical identity of the women steeped in romanticized images of the pre-Civil War slaving South. The history of this sweet street food is not entirely sweet.

Click here for a calas recipe

December 10, 2015

A Bout of Dickensian Anxiety

By Beth Dunn (Former Regular Contributor)

At first glance, the tale of Charles Dickens’ rise to fame and fortune would seem to be one of unhalting advances towards the pinnacle of success that he had achieved by the end of his life. But even the mighty Boz suffered from serious doubts about his skills as a novelist, and his ability to support himself purely by the labor of his pen.

And what do writers do when we think the well has run dry?

We panic.

Charles Dickens had already seen early success — and lots of it — as the author of The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, A Christmas Carol, and Barnaby Rudge, along with assorted other bits and pieces.

Bleak House, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, Little Dorrit, and Our Mutual Friend still lay ahead of him, though of course he couldn’t know that.

All he knew was that he had a large and constantly growing family to support, and he was suffering increasingly frustrating bouts of writers block. In the midst of writing Dombey and Son (never heard of it? there’s a reason for that), Dickens was so uncertain of his future prospects as a novelist that he took on a job he almost certainly knew he would hate from the start — editor in chief of The Daily News.

Oh, sure, he had been an editor and contributor to various journals from time to time. And he had started his writing career as a sort of beat reporter in Parliament, winning the job largely on the merits of his impressive skills at taking notes by shorthand. And he had always been a crusader against what he recognized as the vast social injustices of the day, which the Daily News promised to rail against until Something Was Done.

On paper, it seemed like the perfect fit. The fledgling newspaper’s financial backers wanted a prominent editor who would drive up sales and help their new project compete against the very popular — and very right-wing — Morning Chronicle. And Dickens, who was suffering a serious bout of nerves, wanted a steady paycheck.

You know, in case this whole writing thing didn’t pan out.

Within a matter of days, he knew he had made a dreadful mistake.

Eventually, he convinced his best friend (John Foster, who did have a background in journalism) to take over as editor. Dickens had almost from the start hated the daily grind of the paper, hated the pressure, hated being pulled in so many different directions by so many competing interests, hated the corruption of the press in general, of which he was now a part.

So he quit, after only a few weeks.

But the experience was not without its upsides.

First, Dickens had realized that his occasional bouts of writers block were largely due to his absence from the city streets of London. He’d been traveling abroad with his family in recent months, and the quiet countryside was doing nothing for his concentration. When he was free to prowl London’s dark and sooty streets at night, he was in his element again at last, and he was back to his old prolific self.

Second, he had finally found decent occupation for his father, a bit of an unrepentant sponge and perennial debtor on whom Dickens would later base his Mr. Micawber. John Dickens had been installed as head of the newsroom at the Daily News, and had taken to it, quite to everyone’s surprise, extraordinarily well. He showed up, he managed people, he got the job done. It was really quite remarkable, and even his son acknowledged that he’d finally found his niche.

And finally, perhaps most importantly, Charles Dickens had learned the lesson that so many writers have to learn the hard way.

We’re just not really fit for much else, when it comes right down to it.

So we had better just get down to it.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, and makes a habit of reading far too much into the life stories of her 19th century literary heroes.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in December 2011.

December 9, 2015

Museum Mysteries: When the Artifact You Have is Not the Artifact You Thought

By Michelle Marcella (Guest Contributor)

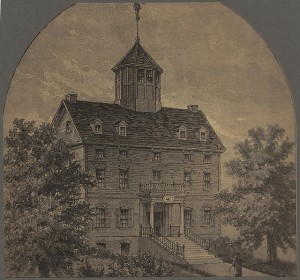

Boston’s Province House. Courtesy the Boston Public Library.

When the Massachusetts General Hospital was chartered by the Massachusetts Legislature in 1811, little thought had been given to just where in Boston the hospital might be housed. To remedy this, the Commonwealth deeded the colonial Province House to the newly minted Mass General for use as it saw fit. Although deemed unusable as a hospital, the trustees leased the Province House. It became the cornerstone of an endowment, one that would require almost seven years of growth before shovel was put to ground in 1818.

Built as a mansion for a wealthy London merchant in the late 17th century, the Province House eventually became the seat of the British government, housing a succession of royal governors. It was filled with artifacts that would become symbols of colonialism, including the royal coat of arms of the reigning monarch. The last of those would be King George III, whose rule would start a revolution.

When the Province House passed into MGH’s hands, a number of these artifacts—including the coat of arms and the building’s copper weathervane in the shape of a Native American archer—came with it. Many of these relics found their way into the collection of MGH surgeon John Collins Warren, who was quite the magpie for items odd and unusual. This was a man who kept a fully assembled skeleton of a mastodon in the front parlor of his Beacon Hill home.

The royal coat of arms: of Queen Victoria, not King George III.

Warren died in 1856, and much of his collection, including his own skeleton, became part of the Warren Museum at Harvard Medical School. Other items, such as the mastodon, would make their way to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. His papers, some family artifacts and the Province House weathervane went to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Other items came back to the MGH; many assumed this included the coat of arms.

Indeed, for many years a royal coat of arms has been part of the hospital’s special collections. Hand carved from hardwood and vibrantly painted, it is a spectacular piece of art. Until recently, many believed it to have hung in the Province House. Unfortunately, it did not: In fact, it displays the heraldry not of George III but of Queen Victoria, whose reign began some 17 years after George III, and a year before the hospital opened its doors to patients.

A look at the archives provides some details. Correspondence informs us that the coat of arms in the MGH collection came to the hospital in 1939 under the mistaken impression that it was the Province House original. It wasn’t until earlier this year that the hospital discovered—through an inquiry about it status—that its coat of arms was not the Province House original. Rather, the original is on display at the Old State House in Boston, and is part of the original Warren collection that was donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Michelle Marcella is the operations and finance manager at the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital.