Holly Tucker's Blog, page 23

October 11, 2015

Hairs of Hippocrates?

by Helen King

Engraving of marble bust of Hippocrates

Credit: Wellcome Library

Did Hippocrates develop a remedy against baldness because he was worried about his own hair loss? As readers of my previous posts here will know, normally when Hippocrates gets dragged into a modern medical discussion it’s to validate whatever the writer is trying to sell; for example, watercress. But in the discussions of baldness, the message is a different one; not that we should look to Hippocrates, but that despite the ‘fact’ that even Hippocrates couldn’t find a cure for it, there may be one now.

The cure for baldness?

I started looking into this because the Wikipedia article on Hippocrates currently contains a claim that ‘The most severe form of hair loss and baldness is called the Hippocratic form.’ The source given is a dead web link, to ‘The dilemma of balding solve by father of medicine Hippocrates”. Healthy Hair Highlights News. 15 August 2011’. Going through the article’s history shows that the sentence was added to the article on 1 October 2011. The original link was reported as dead in April 2012, but I think it’s reasonable to suppose that it originally went to a story that’s very common on the internet to the effect that:

Hippocrates had a personal interest in finding a cure for baldness as he suffered from hair loss. He developed a number of different treatments including a mixture of horseradish, cumin, pigeon droppings, and nettles to the scalp. This and other treatments failed to work and he lost the rest of his hair.

This version comes from a story posted 17 September 2012 on ‘Alopecia World’.

Portrait of Hippocrates, 1665. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Was ‘Hippocrates’ bald?

Clearly this has a lot in common with other myths about the historical Hippocrates, in that it tries to create a person and a story. Hippocrates’ hair was not, however, a fixed point in the long tradition of trying to imagine what he looked like. Sometimes, as here from an image of 1665, he was shown with a full head of hair.

D. Le Clerc, The history of physick…

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

But because one of the texts in the ‘Hippocratic corpus’, The Physician, describes how a doctor should look healthy, one image that probably originated in the late third century BC represented him to match this text, as ‘a well-fed, confident, partly bald elderly man’ (Pinault, p.17). Indeed, sometimes he was shown with his head covered, to hide his baldness, a story taken from one of the earliest attempts to create a biography for Hippocrates, section 12 of the Vita Hippocratis Secundum Soranum. He was shown like this in 1699 by Daniel Le Clerc.

In his 1806 lecture ‘On the opinions and modes of practice of Hippocrates’, Benjamin Rush represented him with plenty of hair, but didn’t specify whether this was on top of his head as well, writing that Hippocrates was Mild in his appearance, and dignified in his deportment, with gray hairs loosely flowing over his shoulders…

So, did the remedy work?

But back to those modern manifestations of the myth of Hippocrates’ baldness. Here, sometimes the remedy is simply a failure. For example, from a 2012 version online, he

personally grappled with male pattern baldness. He prescribed himself and fellow chrome domes a topical concoction of opium, horseradish, pigeon droppings, beetroot and spices. It didn’t stop anyone’s hairline from receding

or from a more recent site which is telling the same story:

Hippocrates himself was plagued by male pattern baldness and concocted a potion which he believed would cure the problem. Containing beetroot, horseradish, pigeon droppings, spices and opium, it was an abject failure.

But the remedy may be even worse than a failure. In some versions, the remedy is not only presented as ineffective, but also as positively harmful. For example, from a hair loss forum in 2005, he:

recommended a putrid mixture of cumin, pigeon droppings, horseradish and beetroot as a cure for baldness. However, the concoction proved disastrous. Hippocrates became ever balder, so much so that, even now, extreme cases of hair loss are referred to as “Hippocratic baldness”.

So, don’t try this yourselves… The story is regularly retold to preface any apparent breakthrough in treating male pattern baldness. For example, in 16 May 2007 The Times described Hippocrates’ remedy as a blend of pigeon droppings, cumin, horseradish and beet-root. Interestingly, an earlier story on the same topic in the same newspaper – ‘Then and now: Baldness’ – instead had Hippocrates slapping on a mixture of opium, horseradish, pigeon droppings and beetroot. It didn’t work. He got so sparse that hairlessness became called “Hippocratic baldness”.

This is just one example of how opium replaces cumin in many of the retellings of the story. For example, Hippocrates used an ointment of opium and essence of roses. His hair failed to grow back. He then tried a formulation of acacia oil and wine. Again, no luck, a version which featured in Charles Vallis, Hair Transplantation for the Treatment of Male Pattern Baldness (1982) as opium with the essence of lilies or roses, mixed with wine and olive oil.

Whose remedy was it anyway?

You may by now be wondering: where does this remedy come from? It is, indeed, from the Hippocratic corpus. But it has noting to do with male pattern baldness, let alone with Hippocrates himself.And it doesn’t include opium. Instead, it’s from the gynecological treatise, Diseases of Women 2.189. Laurence Totelin translates this recipe for hair loss in women as If she loses hair, apply as a cataplasm: cumin or excrement of pigeons, or crushed radish, or with crushed onion, or beet, or nettle (p. 262). Historically, the use of irritant substances – usually combined with something to make the whole thing smell more appealing, as in the lilies and roses in some versions – has been standard for hair regrowth remedies across the ages, whether for men or for women.

Hairs of Hippocrates? No. Nothing to do with the historical Hippocrates, the repetition of this recipe for hair loss rules the internet, and acts as a useful warning that nothing should be taken at face value where Hippocrates is concerned!

Further reading:

Benjamin Rush, Sixteen introductory lectures, to courses of lectures upon the institutes and practice of medicine, with a syllabus of the latter. To which are added, Two lectures upon the pleasures of the senses and of the mind, with an inquiry into their proximate cause, Philadelphia: Bradford and Innskeep, 1811, Lecture 12 pp. 274-294.

Jody Rubin Pinault, Hippocratic Lives and Legends (1992)

Laurence Totelin, Hippocratic Recipes: Oral and Written Transmission of Pharmacological Knowledge in Fifth- and Fourth-Century Greece (2009)

October 9, 2015

What an American Pest did to French Taste and “Terroir”

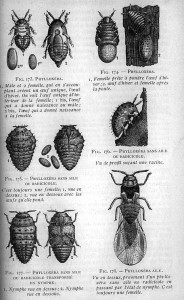

This insect altered the perception of wine

An American louse that annihilated three quarters of French vineyards in the nineteenth century can also claim credit for helping shape the way wine is perceived today.

When phylloxera, an aphid-like insect, was inadvertently introduced to France in the 1860s, it quickly destroyed up to seventy-five percent of the country’s vines, sucking sap from their roots while simultaneously poisoning them. It took awhile to isolate the cause of the dying vines since the insects had always moved on when the roots of the dead plant were pulled up and inspected. It took even longer to ascertain that the insect had been transported from the United States where, ironically, most American vine rootstock was resistant to the insect’s ravages.

As France’s wine stock disappeared, and its winemakers went belly-up, a number of solutions were proposed and implemented. These ranged from aggressive chemical treatments in the vines, to releasing flocks of aphid-eating chickens in the vineyards, to placing toads under the vines to biologically terminate the menace. Nothing worked. France, a country whose very identity was tied to wine, not only faced a dry spell in its daily consumption, but also catastrophic economic consequences.

Finally, it was discovered that by grafting American rootstock to French vines, one could replant vineyards capable of withstanding phylloxera’s attacks. By the last quarter of the century the plan was in widespread implementation, and the country was on the route to a vinous recovery.

Still, there were doubters. The “Chimistes,” proponents of a chemical attack, squared off with the “Américanistes,” proponents of using American rootstock, who, among other things, appeared unpatriotic in the eyes of the former. It seemed like sacrilege to create Frankenstein-like vines, tarnishing the purity of France’s national beverage with rootstock from the very country that caused the disaster

Still, there were doubters. The “Chimistes,” proponents of a chemical attack, squared off with the “Américanistes,” proponents of using American rootstock, who, among other things, appeared unpatriotic in the eyes of the former. It seemed like sacrilege to create Frankenstein-like vines, tarnishing the purity of France’s national beverage with rootstock from the very country that caused the disaster

Debates ensued on how American roots would change French wines. Some reports stated that the American rootstock produced grapes with more sugar and higher acid. Others contested these findings. Myriad other concerns included grape yields and how the longevity of wines would be affected. Most of all, producers and drinkers alike worried that American rootstock would affect the taste of the wines. Might it be that French wines would no longer taste entirely French?

Scientific authorities attempted to allay concern, reassuring the public that it was predominantly the “terroir”- that is, the soil and the geographic specificity of the vineyard – not the grape varietal or root type that gave wines their flavor. They promised that the inimitable flavor of France’s best wines would not be compromised. French wines would remain just as French as ever, notwithstanding the use of American varietals.

What is interesting to note is that, though the notion of terroir had already been around for hundreds of years, the French began to think of their wines in evermore terroir-specific terms in the years and decades following the attack of phylloxera. Flavors were increasingly correlated with the soil and its regional particularities (e.g. the different characteristics of the micro-regions of Burgundy) rather than, say, the grape type (e.g. Pinot Noir), which continues to be an essential identifying characteristic in the United States.

In other words, an American louse is in all likelihood partially responsible for the cultural construction of terroir in the French imagination, and the way wines are tasted today.

A handful of French producers currently experiment with native French rootstock called “Franc de Pied.” The vines succumb to phylloxera quickly unless they are planted in sandy soils, and even then have a short lifespan. The wine flavors, however, are startlingly different than those planted on American rootstock.

October 8, 2015

Early Surgery and Cautery: Or How to Boil a Puppy

By Holly Tucker (Editor)

How did early surgeons control bleeding? Many of you can guess the answer. For as horrific as it sounds, cautery with hot metal instruments and boiling oil were the methods of choice in the 16th and 17th centuries.

What is less well-known, however, is that the practice was thoroughly critiqued by Ambroise Pare, one of the most prominent French surgeons of the early-modern period.

In his First Discourse Upon Wounds Made by Gunshot (published in English in 1617), Pare experimented with salves as a way to avoid causing his patients the intense pain that comes–understandably–with pouring boiling oil on open wounds.

“I observed the method of the other Chirgurians in the first dressing of [gunshot] wounds, which was by the application and infusion of the Olye as hot as they could suffer it…:wherefore I became embolded to do as they did. But in the end, my oyle fayled me, so that I was constrained to use in steede thereof, a digestive made of the yolke of an Egge, Oyle of Roses and Terebinth. The night following, I could hardly sleepe at mine ease, fearing lest that for want of cauterizing, I should find my Patients on whom I had not used the aforesayed Oyle, dead and impoysoned; which made mee to rise earely in the morning to visit them: where beyond my expectation, I found those on whom I had used the disgestive medicine, to feele but little paine, and their wounds without inflammation or tumor, having resting well all that night.

The rest, on whom the aforesaide Oyle was applyed, I found them inclining to Feavers, with great pain, tumor, and inflammation about their Woundes: then I resolved with myselfe never to burn so cruelly the wounded Patients by Gunshot anymore.”

Pare continued to pursue his studies on post-surgical balms. Not long after, he went to Paris and met with the King’s surgeon. This high ranking surgeon gave Pare the “receipt” for his own balm. And, I should add here my history of medicine students cry out in protest when I remind them that “whelps” mean puppies…

RECIPE

“He sent me to fetch him two young whelpes, one pound of earth-wormes, two pounds of the oyle of Lillies, six ounces of the Terebinth of Venice, and one ounce of Aqua-vitae: and in my presence he boiled the whelpes alive in the saide Oyle, until the flesh departed from the bones. Afterward, he tooke the wormes (having before killed and purified them in white wine, to purge themselves of the earth which they have always in their bodies) being so prepared, he boyled them also in the said Oyle till they became dry, this he strained through a Napkin, without any great expressions, that done, he added thereto the Terebinth, and lastly, the Aqua-vitae, and called God to witnesse, that this was his Balme which is used in all wounds made by Gunshot.”

I’ll stick with neosporin, bactine, and my favorite hand lotion…Thanks.

Image: Ambroise Pare, De la methode curative des playes, et fractures de la teste humaine (1651). Wellcome Library, London

This post was originally published on Wonders & Marvels in February 2009.

October 7, 2015

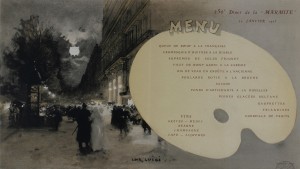

Memorable Meals

By Michael Garval, Guest Contributor

When my father died in 1995, my mother gave me a small, rectangular box containing a miniature Torah scroll tied round with a white silk ribbon. It was my father’s 1949 bar mitzvah menu, with information on the Newark, New Jersey venue; insets of the Ten Commandments, five on each side; a black and white photo of Dad at 13, serious in his suit jacket and floral tie; and haphazardly-spelled items like “hors d’ouveres” or “Baked Ontario Whitefish a l’Espagnole,” homey “Stuffed Derma” amid the fancified French offerings, and “Cafe Noir,” a classy, kosher way to end the meal in a pre-Coffee-Mate era.

A commemorative menu by Luigi Loir for the 250th dinner of “La Marmite,” a Parisian literary-artistic association. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

As it turns out, my heirloom was an emblematic example from the tail end of an international illustrated menu vogue that began in the nineteenth century. Capitalizing on the collecting craze that accompanied this vogue, menus were often designed as keepsakes, reminders of special occasions and family milestones.

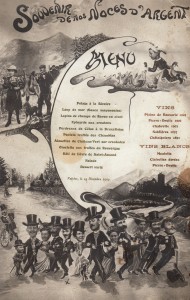

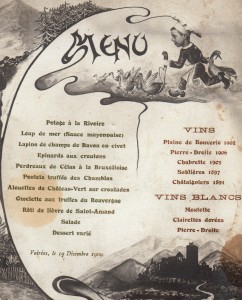

An illustrated menu from 1909 provides an intriguing example. Printed on what looks like a postcard, it commemorates a silver anniversary celebration in Valréas, a small town in the Vaucluse. Comic vignettes surrounding the bill of fare depict the local landscape, as a little scullion chases fowl with a big knife or, in the foreground, the elegant couple and their friends dance with arms joined. Most of the illustrated material is drawn, but with photographs of the figures’ heads inserted. While the guests gaze outward, the husband and wife look lovingly at each other.

Who were they? Their formal attire, the refinement of the dinner, plus the expense of this elaborately-wrought souvenir, indicate a couple of some means. And the exuberant art nouveau type used for the titles, like the swirling lines framing the bill of fare, suggest style and sophistication.

These folks and their pals also knew how to have fun. Flashing smiles, they carouse and relish inside jokes: a fellow at far left, striped jersey beneath his evening coat, leans against a bicycle and sticks out his tongue; another, at far right, teeters as he tries to fish his fallen top hat with a walking stick. The vignette at upper left adds a multi-layered verbal-visual gag. Whimsical provisioning scenes abound in illustrated menus, like the little chef chasing birds, and here the couple returns from hunting with a rabbit and wolf, presumably for the anniversary feast. Like M.F.K. Fisher we might wonder “how to cook a wolf,” but a pun provides the answer, as the bill of fare includes both rabbit and sea bass—in French, loup de mer or “sea wolf.” These animals could also signify sexual initiation and reproduction: in French “to see the wolf” alludes to a girl’s loss of virginity, and rabbit is a symbol of fertility. So perhaps the hunting trip acts out the couple’s conjugal journey from wedding night through parenthood.

There are no clues, however, about people’s identities, save a little cross, marked in pen beneath one figure, referencing a handwritten message on the back:

Guillou Engraver

at Le Portalou

near Postman Rouhet

in St. Jean

beneath the ✗ Louis Guillou, Jr.

This raises more questions than it answers. The first part looks like an old-fashioned, rural address, but the card was never sent (no stamp, no postmark), nor was the otherwise blank, undivided back made for sending (post-1905 backs were divided, and titled “Postcard,” with sub-headers indicating spaces for “Correspondence” and “Address”). Why was young Guillou at the party, or at least depicted there? Next to the bride, their arms linked, he seems a close friend or relative. Perhaps the couple’s apparent ties to the Guillou family and print shop facilitated or even prompted their choice of a fancy—and fanciful—illustrated menu? Or maybe Guillou wasn’t there but, Renaissance style, inserted a self-portrait in the scene, like Botticelli in The Adoration of the Magi. Whether present or not, Guillou might have used the menu as an improvised business card, noting his contact information for someone interested in a similar order.

What about the meal? Belle Epoque banquets probably procured many items locally, but it wasn ‘t yet fashionable to highlight their local provenance. In the age of Escoffier, menus as ambitious as this also favored generically French national fare, a bias only mitigated somewhat after World War I by rising interest in regional cuisine. So it’s all the more remarkable to find here a resolutely local approach to food and wine. Whether larks from Château-Vert, hare from the Saint-Amand ridge, or truffles from Le Rouvergue, the featured ingredients come from within 120 km., many from within 20. Instead of the holy trinity of Burgundy-Bordeaux-Champagne de rigueur elsewhere, the wines all come from small local producers, identified by domain names, save one white designated by local varietal, “clairette dorée,” better known as bourboulenc. And, while we can’t know how the food and wine tasted, the menu does exhibit relics from the meal—a grease stain over the food listing and, at far right, beneath the VINS BLANCS section, a red wine stain—inadvertent but tangible reminders of the festivities.

‘t yet fashionable to highlight their local provenance. In the age of Escoffier, menus as ambitious as this also favored generically French national fare, a bias only mitigated somewhat after World War I by rising interest in regional cuisine. So it’s all the more remarkable to find here a resolutely local approach to food and wine. Whether larks from Château-Vert, hare from the Saint-Amand ridge, or truffles from Le Rouvergue, the featured ingredients come from within 120 km., many from within 20. Instead of the holy trinity of Burgundy-Bordeaux-Champagne de rigueur elsewhere, the wines all come from small local producers, identified by domain names, save one white designated by local varietal, “clairette dorée,” better known as bourboulenc. And, while we can’t know how the food and wine tasted, the menu does exhibit relics from the meal—a grease stain over the food listing and, at far right, beneath the VINS BLANCS section, a red wine stain—inadvertent but tangible reminders of the festivities.

The high seriousness of my dad’s bar mitzvah menu befits both a young person’s ritual passage into adulthood, and his family’s striving toward middle-class respectability. In contrast, the Valréas anniversary menu displays a light-heartedness consonant with an established middle aged couple marking a quarter century of marriage, with all its joys and tribulations, confident enough in who they are to horse around in their Sunday finery, and serve local food and wines rather than more aspirationally national cuisine. But the two menus share a common purpose. Each is doubly commemorative, a family memento masquerading as another sort of collectible, either a faux postcard or an ersatz sacred scroll. Souvenirs of memorable meals, these are artifacts to be cherished.

Michael Garval, Professor of French and Director of the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Program at North Carolina State University, also serves as Associate Editor of the journal Contemporary French Civilization. The author of “A Dream of Stone”: Fame, Vision, and Monumentality in Nineteenth-Century French Literary Culture and Cléo de Mérode and the Rise of Modern Celebrity Culture, he is working on a book about the origins of the celebrity chef in post-revolutionary France.

October 5, 2015

Drink Snake Venom–If You Have a Steel Mustache

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Can one drink snake venom and live to tell the story, as in an ancient tale from the Caucasus?

Snake bite and venoms were much dreaded in classical antiquity. Scythian archers of the Caucasus region and steppes north of the Black Sea were notorious for deadly arrows dipped in snake venom and other noxious substances. Recipes for Scythian arrow poison called for venom, rotted viper corpses, human blood, and animal dung mixed in a leather pouch and allowed to putrefy. Even a scratch contaminated with such a concoction of venom and pathogens would cause a fatal suppurating wound.

King Mithradates VI of Pontus on the Black Sea was celebrated for his universal antidote, said to make him immune to all poisons and venoms. The recipe is lost but venom and minced viper were among the reported ingredients in his Mithridatium. Mithradates demonstrated his immunity by drinking snake venom with no ill effects. Mithradates understood that snake venom can be ingested safely as long as it does not enter the blood stream, through abrasions in the mouth, throat, or the digestive tract (see http://www.wondersandmarvels.com/2012...)

Drinking snake venom figures in some interesting ancient tales from Circassia and Abkhazia (between the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea) recently translated by John Colarusso in Nart Sagas from the Caucasus. In one saga, foes plot to kill a powerful hero by placing seven poisonous snakes in a large drinking horn. Another story features Narjkhyaw, a superhero with a mustache of steel. His enemies offer him a cup of wine mixed with a soup of venom, blood, and flesh of two poisonous snakes, one from the mountains and one from the seashore, both red. The Caucasian viper (Vipera kaznakovi), Black Sea viper (Vipera pontica), and Orlov’s viper have dark red and black patterns.

In the tale, Narjkhyaw compels two of his enemies to drink first and they die horribly. But when he drains the cup, his steel mustache strains out the poisons. Setting down the cup, he casually picks the snake bones out of his mustache and “his stomach did not even rumble.” The story suggests that the venom was digested harmlessly while the decomposed snake flesh, infected with lethal bacteria, was filtered out by the hero’s metal mustache.

Further reading: Adrienne Mayor, The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy; Adrienne Mayor, Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs; John Colarusso, Nart Sagas from the Caucasus (Princeton University Press, 2002 paperback forthcoming 2016)

September 28, 2015

From Confucius to Air Traffic Control

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

In 130 BCE, the Chinese emperor Han Wudi came up with a new idea for how to choose government bureaucrats. He established a civil service of Confucian scholars, known in English as mandarins, who earned their positions by passing a standardized examination. The system still favored those from privileged families who could afford to give their sons a formal education. But at least in theory, getting a government job in imperial China now depended on what you knew instead of who you knew or what family you were born in.

In 130 BCE, the Chinese emperor Han Wudi came up with a new idea for how to choose government bureaucrats. He established a civil service of Confucian scholars, known in English as mandarins, who earned their positions by passing a standardized examination. The system still favored those from privileged families who could afford to give their sons a formal education. But at least in theory, getting a government job in imperial China now depended on what you knew instead of who you knew or what family you were born in.

In Wudi’s day, the examinations tested candidates’ understanding of the tenets of Confucian moral and ethical thought on which Han dynasty government was based–the equivalent of asking candidates for jobs in the United States government to pass a test on the Magna Carta, the Constitution, and the Federalist papers. Over time, the examinations became more and more divorced from the realities of government. By the Manchu dynasty of the seventeenth century, candidates were tested on their knowledge of Chinese history, their ability to compose poetry, and the quality of their calligraphy.

Wudi’s civil service exams controlled who got a government job in China from the seventh century CE through 1905, when the system was abolished in response to pressure from a new western-educated elite. The west didn’t adopt the concept until the nineteenth century. In 1853, the British East India Company was the first European power to use competitive examinations as a means of reforming an increasingly corrupt system, one in which positions were acquired through patronage and purchase. The East India Company consciously copied the Chinese exam system, creating a class of “new Mandarins”.

Other western governments, faced with the hazards of civil service based on “who you know”, thought Wudi’s idea that government employees should pass a test proving their fitness for government service was a good one. The United States entered the game in 1883, after a disgruntled would-be federal employee assassinated President James Garfield. Civil Service exams controlled who got a job in the United States civil service until 1978, when the general civil service examination was abolished. Today, civil service exams are still required for jobs requiring a specific set of skills, such as air traffic controllers and intelligence agency linguists.

September 21, 2015

Sakala: A Cultural Exchange Gone Bad

by Harvey Blustain, Guest Contributor

We take it for granted that cultural exchanges invite understanding and harmony among different peoples. But those exchanges don’t always go according to plan, and sometimes they turn disastrous. Such was the case of the first Congolese boy brought back to Belgium for an education.

Lieutenant Liévin Van de Velde first arrived in the Congo in 1881. Like many officers sent to establish King Leopold’s personal empire in the vast river basin, he had to assume many roles. He built trading stations, fended off native sieges, negotiated treaties with the chiefs, and mapped the unknown terrain. As head of the station at Vivi, he organized supplies and provisioned the stations upriver. And like his compatriots, he was convinced that the European civilizing mission was “a generous idea, a glorious goal.”

Lieutenant Liévin Van de Velde first arrived in the Congo in 1881. Like many officers sent to establish King Leopold’s personal empire in the vast river basin, he had to assume many roles. He built trading stations, fended off native sieges, negotiated treaties with the chiefs, and mapped the unknown terrain. As head of the station at Vivi, he organized supplies and provisioned the stations upriver. And like his compatriots, he was convinced that the European civilizing mission was “a generous idea, a glorious goal.”

But Van de Velde was unusual in his empathy for the natives. When smallpox broke out, Van de Velde constructed a sanitarium for the sick Africans and then spent six dangerous weeks caring for them. He persuaded some tribes to discontinue the practice of human sacrifice. Recognizing that the treaties, which granted the Belgians full sovereignty, made the chiefs apprehensive and suspicious, he argued that chiefs should retain their crown rights.

Illness forced Van de Velde back to Belgium in 1883 but he returned to the Congo in 1885 with the mission of suppressing crimes being committed against Africans in the lower Congo. This assignment, according to the entry on Van de Velde in Belgian Colonial Biography, “permitted him to engage in a study of the native mind (mentalité indigène); he drew near the blacks to better understand them, to initiate them into our civilization.” His journal from that trip, serialized after his death in Le Congo Illustré, contains innumerable observations on native culture, diseases, languages, food, political organization, religion, taboos, law, calendar, counting system, costume, tattoos, kitchen tools, houses, greetings, weapons, diplomacy, marriage, and funerals.

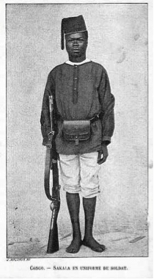

As further evidence of his ethnographic bent, Van de Velde was the first Belgian to bring a Congolese boy to the mother country for an education. His young ward was Sakala, the son of king Mambuco near Vivi on the lower Congo. When he arrived in Belgium in 1885, Sakala was the object of curiosity and lavish attention. Receptions in his honor were held throughout Flanders. His image was sold on post cards, such as that reproduced here. Van de Velde gave many lectures about the Congo and often brought Sakala with him, a kind of living show-and-tell. In 1888, following Van de Velde’s death in Africa from fever, the citizens of Ghent built a memorial to him in a public in park: a rock grotto topped by a statue of Sakala.

As further evidence of his ethnographic bent, Van de Velde was the first Belgian to bring a Congolese boy to the mother country for an education. His young ward was Sakala, the son of king Mambuco near Vivi on the lower Congo. When he arrived in Belgium in 1885, Sakala was the object of curiosity and lavish attention. Receptions in his honor were held throughout Flanders. His image was sold on post cards, such as that reproduced here. Van de Velde gave many lectures about the Congo and often brought Sakala with him, a kind of living show-and-tell. In 1888, following Van de Velde’s death in Africa from fever, the citizens of Ghent built a memorial to him in a public in park: a rock grotto topped by a statue of Sakala.

After two years in Belgium, Sakala returned to the Congo. Major Charles Liebrechts, who was in the Congo at the time, claimed that Sakala’s stint in Belgium had spoiled him rotten and taught him to regard Europeans with disdain. Referring to Sakala as a “pseudo-prince” and the “self-styled son of a great king,” Liebrechts reports that back in the  Congo, Sakala refused to obey Europeans and encouraged insubordination among other Africans. When Van de Velde became fatally sick, Sakala “did not provide a moment of care” and when Van de Velde died Sakala orchestrated the pillage of his baggage. Sakala was later found guilty of theft and during the Arab Wars betrayed the Belgian state. “And that,” concludes Liebrechts, “was the story of the first Congolese native to be socialized by a stay in Europe.” It was an early experiment in international living, and it ended very badly.

Congo, Sakala refused to obey Europeans and encouraged insubordination among other Africans. When Van de Velde became fatally sick, Sakala “did not provide a moment of care” and when Van de Velde died Sakala orchestrated the pillage of his baggage. Sakala was later found guilty of theft and during the Arab Wars betrayed the Belgian state. “And that,” concludes Liebrechts, “was the story of the first Congolese native to be socialized by a stay in Europe.” It was an early experiment in international living, and it ended very badly.

Harvey Blustain is the author of Ambition: A Natural and Cultural History. A retired anthropologist and consultant, he lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Harvey Blustain is the author of Ambition: A Natural and Cultural History. A retired anthropologist and consultant, he lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Photos: Portrait of Van de Velde from Le Congo Illustré: Voyages et Travaux des Belges dans l’Etat Indépendant du Congo, Vol. I, No. fasc. X. 1892. Copy on microfilm in Special Collections & University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, Oregon.

Postcard portrait of Sakala from Albert Chapeaux, Le Congo: Historique, Diplomatique, Physique, Politique, Économique, Humanitaire & Colonial. Brussels, 1894.

Memorial in Ghent to the Van de Velde Brothers.

September 18, 2015

Silent Cinema Flashbacks

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

Audiences in the twenty-first century are very familiar with the filmic convention of the “flashback.” Most often, flashbacks serve to fill the viewer in on a character’s past, and sometimes form an integral part of the structure of the narrative (in series like Lost and Orange is the New Black, for example). In the psychological domain, however, “flashbacks” are usually associated with negative experiences and suppressed memories that return uninvited. In many films –war films especially—both types of flashback are combined: hazy, point-of-view shots take us inside the mind of a traumatized protagonist and offer us a film-within-a-film, a visual representation of their internal rewind and replay.

Kador Cliffs

The association between film and memory is as old as cinema, and the silent film director Léonce Perret’s movies offer a particularly intriguing early example. Perret (1880 – 1935) was trained as a theatre actor, but was quick to recognize the potential of cinema and is praised today for his innovative shot composition and editing. In more than one film, he explored the potential of film to capture and restore memory in traumatic circumstances. This trope is most pronounced in the film he directed in 1913 for Gaumont, Le mystère des roches de Kador, marketed in English-speaking countries as Kador Cliffs.

After the attempted murder of her lover by her villainous uncle and a narrow escape on boat, the heroine of the film, Suzanne, collapses and awakes traumatized with no memory of the events that transpired. In an attempt to help cure her, Suzanne’s lover Jean consults “Dr. Williams” (Anglophone in the original French intertitles too), who agrees to film and screen a reconstruction for the amnesiac heroine in order to restore her memory. As the doctor speaks to a white-coated assistant, Jean casts his eyes to Williams’ publication, and the audience sees the close-up of a printed text that exclaims, of cinema: “The wonderful invention recently adopted in mental medicine is of extreme importance.”

Jean-Martin Charcot’s legacy

In a scene remarkably redolent of Charcot’s clinic, we see the disorientated Suzanne – in a long white gown, with her dark her loose– approach the screen depicting the incidents at Kador Cliffs (the film within the film). She is drawn towards it, illuminated by the light of the screen. After obvious emotional turmoil, she turns and collapses into the arms of the observing medical attendants. She then comes to and recognizes Jean, her memory fully restored. The climax of the film is resolved by a film.

What is striking about this early “flashback” scene, aside from its imagery, is that the “flashback” is external to Suzanne. Cinema had a special relationship to memory through its physiological, hypnotic effect rather than through its psychological content. This reflects a conviction about the bodily nature of emotion that was central to the contemporary understanding of both trauma and film at the outbreak of the First World War. Flashbacks in silent cinema encapsulated the medical and cultural attitudes of their time, and have evolved as a filmic and narrative device along with attitudes to trauma.

For more on Léonce Perret and his work, see:

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret. Cinématographiste (Niort: Association “Cinémathèque en Deux-Sevres”, 2006)

September 15, 2015

The Nazi Poet: Baldur von Schirach in Nuremberg Prison

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels regular contributor

A few years ago, while researching my book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII (PublicAffairs, 2013), I received exclusive access to the papers of one of my subjects, US Army psychiatrist Douglas M. Kelley. Among the many unexpected documents I found in the archival collection kept by the Kelley family was a handwritten manuscript of poetry.

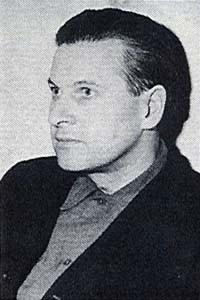

Baldur von Schirach at Nuremberg Prison

Its author was Baldur von Schirach, the longtime leader of the Hitler Youth movement and a former governor-general of Vienna. At 38, he was the youngest of the 22 top German leaders and high-ranking military officers held by the Allies at the end of World War II for trial by the International Military Tribunal on charges of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity. More than most of the other defendants, in Kelley’s judgment, Schirach seemed remorseful for his role in the Nazi atrocities and capable of rehabilitation.

While in prison, Schirach turned to his hobby of writing poetry as an escape from boredom and depression. Sometime during the fall of 1945 he submitted for Kelley’s review a poem entitled “Dem Tod” (“To Death”). It sufficiently impressed Kelley to keep it among his personal papers. Here it is in English translation:

To Death

Your dark eye I have so often seen

That you have become like an old friend to me.

When the bullets scourged, you stood at the mark

And looked at me. To the left and right fell

My neighbor. Yet you turned away.

I greeted each grave later, all alone.

When the bombs burst from the sky,

You drew to me, the house’s silent guest.

Yet you have not done your work on me.

I know, my friend, that your eye is on me.

Although perhaps a self-absorbed work, it undoubtedly conveys meaning and feeling. Many of the captive German leaders had inflated literary pretensions — particularly Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg, and Albert Speer — but Kelley believed that Schirach’s poetry showed more merit than the writerly works of his colleagues.

In the end, the Nuremberg judges dealt Schirach a more lenient sentence than some of his fellow defendants. He served 20 years in Spandau Prison, was released in 1966, and died eight years later at the age of 67.

Further reading:

Eastwood, Margaret. “Lessons in Hatred: The Indoctrination and Education of Germany’s Youth.” The International Journal of Human Rights, 2011, Vol.15(8), p.1291-1314.

Kater, Michael H. Hitler Youth. Harvard University Press, 2006.

September 14, 2015

Peeing like a horse?

by Helen King (monthly contributor)

I was watching Peter Greenaway’s movie The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) again last week. Set at the end of the seventeenth century, it opens with a series of landed gentry types gossiping, often aiming to shock. After telling them a story from her childhood, one of the beautifully-dressed women states confidently “I used to pee like a horse. I still do.”

If you look up “pee like a horse” or “piss like a horse” you’ll find various statements about just how spectacularly a horse can urinate. But knowing rather too much for my own good about the history of medicine, I started to wonder whether this was all there was to her claim. Greenaway’s women are often pretty highly-sexed individuals and this one is no exception. Perhaps there’s something here about her body being more open, more free, than that of a respectable woman should be.

Peeing like a virgin?

The sixteenth-century physician Laurent Joubert published two collections of what he called “popular errors” – beliefs that were held widely in his native France but which he wants to show are mistaken. One which he reports is the notion that, because she has a narrower urinary channel, a virgin can “piss straight and far” in an “unfettered and clear” manner which is a “beautiful mark of maidenhood”. Is this about quantity, or style? Another is that giving a virgin dock leaves to smell will make her urinate immediately.

These popular beliefs went back to various medieval medical treatises. De secretis mulierum, once wrongly attributed to Albertus Magnus, is a medieval Latin text which was translated into German and French. It says that virgins’ urine is clear and sparkling, but once they have had sex their urine becomes muddy because it contains blood and sperm. Golden urine is a dangerous sign because it means the virgin is heating up with sexual desire. Why do physicians need to look at urine? Because women can conceal the truth of their sexuality so “a man must turn to their urine”. The writer also states that true virgins will urinate the moment that they smell, not dock leaves, but the fruit of a lettuce.

The gardens of Adonis

Lettuce is an interesting vegetable here. In ancient Greece, at the height of summer, women would plant little pots of seeds of lettuce, wheat, barley and fennel in pots and baskets on their roof-tops in honour of the god Adonis. These “gardens of Adonis” would spring to life quickly in the hot summer sun, but shrivel up and die just as rapidly. The classicist Marcel Detienne saw here an analogy with the life and death of Adonis; sexually precocious, he died before his prime, gored by a boar, his body found in a bed of lettuce. There’s a reference to the rapid growth of the seeds in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 1:

Thy promises are like Adonis’ garden/That one day bloomed and fruitful were the next.

The image on the right shows a Victorian painting in which the women hold the gardens of Adonis over their heads as they run to the sea. In this ritual and in the myth behind it, lettuce is highly sexual.

The sound of urine

So is Greenaway’s character revealing her sexual experience, or claiming a lack of it? The movie is not without its classical references. There’s a significant section near the end where the lady of the house retells the story of Hades, Persephone and the pomegranate: symbol of fruitfulness (all those seeds) but also of death, a point graphically made in this scene, when its blood-like juice is squeezed out.

Perhaps that reference to peeing like a horse contains some modern ‘popular error’ that the way a woman urinates reveals her level of sexual experience. And it’s not just the volume: it’s also the sound. Albertus Magnus’ contemporary William of Saliceto says a virgin ‘urinates with a very delicate hiss and indeed takes longer than a boy’ because her body is ‘tighter’ than that of a sexually experienced woman. If a virgin is expected to pee in a delicate way, then Greenaway’s character is certainly not a virgin!

Marcel Detienne (1977) The Gardens of Adonis: Spices in Greek Mythology (Princeton University Press; French original 1972)