Holly Tucker's Blog, page 25

August 18, 2015

The most remote layover in American aviation

By Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

On a world map, Shemya Island appears as the tiniest of specks, if it appears at all. Yet this mostly uninhabited part of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands chain has played an important role in the history of aviation, as I learned when I researched and wrote Non-Stop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

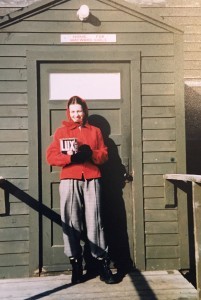

Northwest Airlines stewardess Phyllis Curry in front of the living quarters on Shemya Island, c. 1949

I first heard about Shemya from a retired stewardess named Phyllis Curry, who during the late 1940s worked on some of the earliest Northwest Airlines flights connecting the Continental United States with Asia. Using the “Circle Route” that went over the globe’s far northern reaches, these Northwest flights had to make several refueling stops. One was at Shemya, which must rank as the most remote and unlikely way station in the history of American commercial aviation.

Before Northwest’s use of the island, it had served the U.S. as a World War II military base. Set between the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea, the eight-square-mile island suffered from fog, strong wind, and desolation, but it allowed U.S. forces to combat Japanese incursions into Alaska and the North Pacific. After the war, Northwest took over the retired military facilities on the island.

During layovers to and from the Far East, stewardess Curry shared with other flight attendants a converted Quonset hut, which for a time bore a sign that read, “Home for Wayward Girls.” She recalled: “Because of all the snow, we couldn’t walk around, so [airline staff] would pick us up and drive us to meals which were given in another Quonset hut.” In their idle hours, employees played marathon poker games, hunted the Army’s garbage dump for souvenirs, and occasionally found stone tools from previous Inuit residents. They also kept track of a dog that had escaped from a Northwest passenger during a refueling stop and ran loose on the island for many years. “Whalebone sometimes washed up on the island…. I thought, “If only my mother could see me now,’” Curry said.

Later the U.S. military resumed use of Shemya and Northwest moved its refueling operation. Shemya’s military facilities, now called Eareckson Air Station, currently house early-warning radar equipment and are run under the management of a caretaker contractor.

Further reading

Bachman, Justin. “This Remote Island is the Last Place Pilots Want to Land a Plane.” Bloomberg.com, July 29, 2015.

August 14, 2015

The Plight of the Pigeon

By Thomas Parker (Regular Contributor)

In Stardust Memories (1980), Woody Allen referred to pigeons as “rats with wings,” and the moniker has stuck. But the pigeon’s reputation has not always been so low. Pigeons, or doves, another word for the same bird, appear with positive connotations in both the Old and New Testaments, and the ancient Greeks took them to be divine intercessors, interpreting their coos and flights around a sacred oak in Dodona as messages from Gaia, the goddess of the earth.

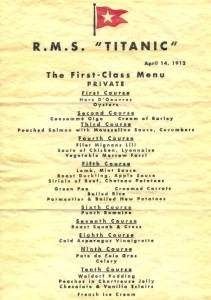

At the table, squab (baby pigeon) was a delicacy in ancient India, Egypt, and Rome. It was widely enjoyed throughout Europe from the Middle Ages on, and served as the seventh course on the Titanic.

That lofty reputation has plummeted in the last century as pigeon populations have flown from rural environs to invade our cities. We no longer focus on their godliness, nor even their juicy “squabness,” but rather their invasiveness as they cross the mental borders we construct to separate animal nature from human culture. The unseemliness of their droppings disgusts, their lasciviousness appalls, the males chasing the females around the park on two feet like ungainly bird rapists, and their scavenging of trashcans and gutters relegates them to the dregs of the animal world.

But, here again, though pigeons are gutter birds today, they once soared high in the collective spirits as an aristocratic animal, considered fine eating by nobles who invited the pigeon onto their estates by building grandiose dovecotes, some of which could house 2000-3000 pairs of pigeons.

Pre-Revolutionary France led Europe in the estimated 42,000 dovecotes it possessed, more than double the quantity of any other country. The dovecote provided a ready source of meat for nobles, but also served as a sort of accessory that announced the wealth, elegance, and prestige of the owner through the stateliness and intricacy of its architecture. Most of all, possessing a dovecote in itself was a privilege reserved by law to noble landowners.

But here too, the pigeons’ flight pattern led to their disrepute. The birds infuriated the serfs, peasants, and country farmers by winging forth from their noble abodes to feed on commoners’ fields, fattening the lord at the expense of the everyman. At the hour of the Revolution, pigeons became a symbol for the noblemen themselves, inciting such anger, that legislative action was taken against the bird.

The first decree stipulated that all people, no matter what their class, should be able to possess dovecotes. But that was not enough: the rage against the nobles was so great that commoners sought revenge, storming the country, destroying dovecotes and murdering the birds en masse. Their moral disgust for the bird did not entirely translate into a physical disgust for its meat, but the net effect was a drastic reduction of the amount of pigeon served on nineteenth-century French tables.

All of this brings us back to flight patterns. If the pigeon’s movements were equated with nature in antiquity, in modernity, the bird’s invasion into human culture and agriculture has led to its plight, relegating it from divine exaltation to earthly execration.

All of this brings us back to flight patterns. If the pigeon’s movements were equated with nature in antiquity, in modernity, the bird’s invasion into human culture and agriculture has led to its plight, relegating it from divine exaltation to earthly execration.

August 13, 2015

How Wind Power Won the American West

By Carol Clark (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

There is something both comforting and mournful about the creak of an old windmill coming to life in a breeze. The metal skeletons and pinwheel faces of windmills tower over the loneliest of places, totems to the people who staked a claim on vast, empty plains, where they stayed attuned to the slightest shifts of weather.

Growing up in northeast Texas, I’d occasionally catch glimpses of these whirling relics silhouetted in the distance, as our car rushed through the scraps of rural landscape separating suburbs and cities. But I didn’t fully appreciate windmills until I went to the annual meeting of the Society of Environmental Journalists last October, held in the West Texas town of Lubbock.

Lubbock is set in the Southern High Plains, where the economy is fueled by oil, gas, agriculture and wind. This year’s SEJ conference was themed: “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over.” Several hundred writers, scientists and policy makers descended on the town. We broke into groups for field trips, moving like flocks of flightless birds across the plains, baked by the relentless sun and scoured by the gritty wind. We learned about the hard-scrabbled history, recent record drought, and possible future scenarios of this remote, yet influential, region.

One of the highlights for me was the story of the humble windmill’s key role in settling parts of America where surface water is scant, including the Southern High Plains.

In 1854, American Daniel Hallady invented a self-governing windmill, which automatically turned to face whichever way the wind blew. Weights allowed the wooden blades to swivel in a way that also controlled the speed of operation, to reduce wear and tear on parts and the chance of breakage in strong winds. It was simple, streamlined and affordable for pioneer families who wanted to tap underground sources of water. Larger windmills sprouted up every 20 miles or so along railroad lines, where they were needed to pump water for steam engines.

A visit to Lubbock’s American Wind Power Center drove home the importance of the windmill to opening up the West. The center’s collection of vintage wind machines gives you an idea of the high regard, and even affection, people must have felt for them. Their makers branded them with romantic names like “Iron Man,” “Eclipse,” and “Star.” Windmill weights entered into the realm of folk art, taking on whimsical shapes of squirrels, horses and roosters.

Wandering beneath the gently whirring blades, I imagined how soothing the sound must have been to people who relied on windmills for their water.

The windmill helped power a sustainable way of life for decades across the Southern High Plains. Things tilted out of balance during the Great Plow Up. The U.S. government artificially raised the price of wheat and encouraged farmers across the Plains states to rip out deep-rooted native grasses and ramp up crop production to feed the troops in World War I. The result was the environmental catastrophe known as the Dust Bowl. During the 1930s, the wind churned up all that loose dirt and spun it into dark, boiling clouds that suffocated toddlers, obliterated the sun and swept away livelihoods.

The dust had scarcely settled when the main lesson of that disaster was largely forgotten: Excess comes at a heavy price.

By the 1950s, advances in electrical pumping technology had made the windmill nearly obsolete. Farmers and ranchers from Nebraska to West Texas could now exploit their underground water supply, known as the Ogallala Aquifer, to an extent never before possible.

It took 12 million years for rain to seep down and fill the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the world’s largest underground water systems. During the past 50 years, we’ve emptied half of it, mainly through intensive irrigation.

So what does the future hold, for West Texas and the rest of us, as the climate warms, the population booms, and the demand for fuel, food, water and other consumer goods keeps growing?

It depends on how you spin the story.

Oil and agriculture boosters downplay the looming questions surrounding our heavy reliance on fossil fuels and industrial-scale irrigation. And West Texans can now boast about renewable energy, since the region produces more wind power than any other state. The old-fashioned windmills have morphed into sleek, high-tech wind turbines. So what if they lack charm: Utility-scale wind turbines, some with blades as long as 120 feet, can generate massive amounts of electrical power.

The “whump-a-whump” of a giant wind turbine in full bore has been compared to heavy sneakers tumbling in a dryer. That’s the sound of progress. And how comforting, to be reminded that we can harness the wind and generate electricity to rapidly dry our latest pairs of designer sneakers.

Carol Clark is Senior Science Communicator at Emory University, where she edits the Web site eScienceCommons.

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in November 2011.

August 12, 2015

Museum Mysteries: Your Brain on Laughing Gas

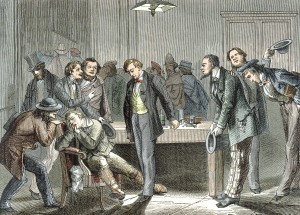

Figuier L. Les Merveilles de la Science ou Description Populaire des Inventions Modernes. Paris, 1868.

By Sarah Alger (Regular Contributor)

While in the dentist’s chair on a recent morning, I contemplated the fact that the mystery of what exactly happened one day in 1845 might in fact be a mystery about the human brain.

On January 21 of that year, Boston’s Daily Evening Transcript ran an ad by a gentleman who “wishes to introduce a new system of Surgery having especial reference to the Extracting of Teeth, by which nearly or quite all the pain which is usually caused by the operation may be avoided. The Doctor proposes to explain his theory to an audience at some public hall, and then proceed to perform operations in extracting teeth for those who will consent to undergo the operation.”

This Doctor, there is little doubt, was Horace Wells, a dentist from Hartford, Conn. His proposition, pain-free dentistry, was revolutionary. His system was the administration of nitrous oxide (laughing gas), with which he had successfully experimented on himself and some of his patients.

The details of his trip to Boston are unclear. He did end up recruiting a medical student to undergo tooth extraction in a public place, but the date and venue remain unconfirmed. Accounts differ about the demonstration itself; some witnesses did not notice any discomfort on the patient’s part, while others claimed he cried out in pain or did show discomfort, and as a result, declared the event a “humbug.” We do know that Wells thought perhaps he had stopped administering the gas too soon, and that he felt dejected, so much so that he returned to Hartford the next day.

My colleague and Massachusetts General Hospital archivist Jeffrey Mifflin notes that the young patient and his friends were planning to inhale nitrous oxide for fun after the demonstration. The patient, high on laughing gas and already in the party mood, might have cried out for the amusement of his friends, Jeff posits.

It was a year later that Wells’s former apprentice William T.G. Morton was responsible for the first successful public demonstration of anesthesia, using ether on a surgical patient at Massachusetts General Hospital (more on that story another time). Thus the field of anesthesia was officially born. Though the past 169 years have yielded refinements in anesthesia drugs and dosing, much remains to be understood about the brain under anesthesia.

Mass General anesthesiologist Emery Brown has spent much of his career pursuing this question, and last month, he published a paper that offers another possible explanation for Wells’s failure. In modern surgery, various types of ether are still in use, and patients are often switched from an ether to nitrous oxide toward the end of the surgery, allowing them to be more easily awakened.

In the paper, published in Clinical Neurophysiology, Brown and colleagues describe monitoring the EEG readings of 19 patients undergoing surgery. High doses of nitrous oxide cause patients to exhibit brain waves similar to those of deep sleep, yet for reasons still unknown, these waves are transient and return to a shallower, more easily rousable state. Wells might very well have administered enough gas; it might have been the patient’s brain that spoiled the fun.

August 11, 2015

The Fair and Gentle Sex or Outlaws?

By Robert Barr Smith (Guest Contributor)

The Fair Sex, the Gentle Sex: women have been called by those fine names throughout history. Unsung for the most part, they built the vast western United States, working alongside their men, bearing their children – and losing some – making homes in the wild new country. And, generally speaking, the ladies were accurately called “fair” and “gentle.”

Belle Starr

But then, there were the others.

Take Joyce Turner, for instance. She didn’t much like her husband Alonzo, nothing unusual for the married state. But she did something about it after complaining about Alonzo to a couple of girl friends. One of them suggested a remedy, and finally said, “Well, are you going to do it or not?”

So Joyce went home and did it, blowing a fatal hole in Alonzo as he slept. Joyce got a life sentence, but still had the panache to tell a reporter:

Alonzo always told me that he wanted

to die in bed. I simply arranged it.

You’ve got to admire Joyce’s way with words.

But there were other ladies who had even fewer admirable qualities, and some who had no trace of decency at all. A good many of the women who turned bad were poisoners; some of those poisoned wholesale. Their victims were not only husbands and boyfriends, their natural prey, but sadly other family members, even their own small children.

Others swung axes, as Lizzie Borden is said to have done; some preferred knives. Some were swindlers or thieves, robbers of banks and stagecoaches. Some were only “molls” in the language of the ‘20s and ‘30s. Some were members of horrendous family murder machines, like the Benders of Kansas, who made travelers disappear.

None of them were loveable; many were downright vile. Maybe the queen of those was Belle Gunnes, whose victims numbered as many as forty or fifty people, including some of her own children.

And since female outlaws were not the usual stuff of the news of crime, the newspapers loved them, cranking out reams of purple prose about their exploits. Those daring deeds were often exaggerated, and their effect was to create more than a few legends. Overdone, occasionally even phony, nevertheless the stories sure did sell papers, and later on, lots of movie tickets.

Some outlaw women were portrayed far beyond their real importance, rather like the Wizard of Oz. Belle Starr is a good example, in fact simply a lady of flexible morals transmogrified into “The Bandit Queen,” as the papers were fond of calling her. Belle helped some, having her picture taken regularly on big horses, or packing a heavy revolver or two.

The ladies of young America were a hardy, courageous breed. But sometimes, one of them proved there was some truth in Kipling’s poem:

The female of the species is more deadly than the male.

Robert Barr Smith is a retired U.S. Army Colonel, Professor Emeritus, University of Oklahoma College of Law. Author or co-author of seventeen books on law and western and military history, he lives today in Missouri’s Ozark Hills.

Robert Barr Smith is a retired U.S. Army Colonel, Professor Emeritus, University of Oklahoma College of Law. Author or co-author of seventeen books on law and western and military history, he lives today in Missouri’s Ozark Hills.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Outlaw Women in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on August 27th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

August Book Giveaways

Schechner, Ulrich, Gaskell, Carter, van Gerbig, “Tangible Things: Making History through Objects”

Matthew P. Mayo, “Hornswogglers, Fourflushers & Snake-Oil Salesmen”

Robert Barr Smith, “Outlaw Women: America’s Most Notorious Daughters, Wives, and Mothers”

August 10, 2015

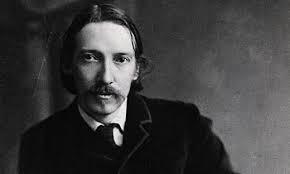

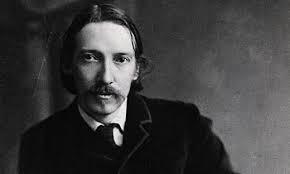

Food For the Soul, If Not the Body: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Trip to California

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

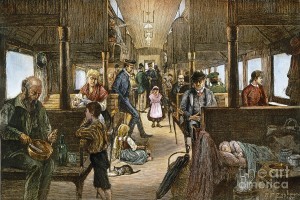

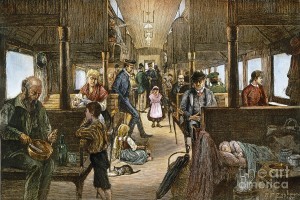

One of the most beautiful and detailed travel accounts of a trip by railroad from the East to the West Coast in the nineteenth century was written by Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1879, the future author of Kidnapped and Treasure Island undertook his own adventurous voyage, from Scotland to San Francisco, in a romantic quest to join the lady of his dreams. Stevenson had met Fanny Osbourne in France and the two had fallen in love, despite obvious obstacles to the relationship – she was married, and ten years his senior. But when Stevenson received a letter from her

One of the most beautiful and detailed travel accounts of a trip by railroad from the East to the West Coast in the nineteenth century was written by Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1879, the future author of Kidnapped and Treasure Island undertook his own adventurous voyage, from Scotland to San Francisco, in a romantic quest to join the lady of his dreams. Stevenson had met Fanny Osbourne in France and the two had fallen in love, despite obvious obstacles to the relationship – she was married, and ten years his senior. But when Stevenson received a letter from her  indicating that she was about to be divorced, he decided to make the strenuous voyage to join her in California. His parents refused to pay, so he bought cheap passage on a boat to New Jersey and then a ticket on an “emigrant train” headed for the West Coast. By the time he reached America he was sick and exhausted. The remaining two-week trip to California almost killed him.

indicating that she was about to be divorced, he decided to make the strenuous voyage to join her in California. His parents refused to pay, so he bought cheap passage on a boat to New Jersey and then a ticket on an “emigrant train” headed for the West Coast. By the time he reached America he was sick and exhausted. The remaining two-week trip to California almost killed him.

Conditions on emigrant trains were difficult. The train made regular stops, three times a day, for food, but this meant that passengers had to rush to whatever eating establishment was closest to the train station and get back to the train car before it departed. Emigrant passengers were rarely given warning of the departing train. This meant that many often went without food, either from lack of money or lack of time.

But Stevenson, remarkably, does not dwell on the punishing conditions of his voyage. Each time he does mention a missed meal or a paltry choice of inedible food, he seems to follow with a description of something beautiful. After reporting a day passed with no food at all, he switches to a description of the amazing richness of place names in America, and how they provide a writer with food for the imagination. “None can care for literature in itself who do not take a special pleasure in the sound of names; and there is no part of the world where nomenclature is so rich, poetical, humorous, and picturesque as the United States of America … The names of the states and territories themselves form a chorus of sweet and most romantic vocables: Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, Florida, Dakota, Iowa, Wyoming, Minnesota, and the Carolinas; there are few poems with a nobler music for the ear.”

But Stevenson, remarkably, does not dwell on the punishing conditions of his voyage. Each time he does mention a missed meal or a paltry choice of inedible food, he seems to follow with a description of something beautiful. After reporting a day passed with no food at all, he switches to a description of the amazing richness of place names in America, and how they provide a writer with food for the imagination. “None can care for literature in itself who do not take a special pleasure in the sound of names; and there is no part of the world where nomenclature is so rich, poetical, humorous, and picturesque as the United States of America … The names of the states and territories themselves form a chorus of sweet and most romantic vocables: Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, Florida, Dakota, Iowa, Wyoming, Minnesota, and the Carolinas; there are few poems with a nobler music for the ear.”

The vast plains of Nebraska were the least able to offer nourishment for his thoughts. The unchanging dullness of this landscape overwhelmed him: “Our consciousness, by which we live, is itself but the creature of variety. Upon what food does it subsist in such a land? What livelihood can repay a human creature for a life spent in this huge sameness?”

At the end of his voyage, Stevenson tells an anecdote that seems to sum up the strange mixture of brutality and nourishing hope that he had come to see as characterizing the experience of a newcomer to America. Seated at the end of a stifling railcar, he had propped the door open with his leg to get some air. A newsboy, annoyed by the encumbrance, kicked him and repeatedly jostled him as he continued to pass back and forth. Robert was feverish, and depressed by the lack of civility. “But suddenly I felt a touch upon my shoulder, and a large juicy pear was put in my hand. It was the newsboy, who had observed that I was looking ill and so made me this present out of a tender heart.”

Thomas Hill, Mount St Helena, Napa Valley

Fanny Osbourne later wrote that her lover arrived in California barely alive. But she was the prize that assured his survival. They were married in San Francisco in May 1880. The newlyweds spent the summer, while Robert recovered his health, in a cabin in the abandoned Silverado mining camp, on the slope of Mount St. Helena.

For Further Reading:

Robert Louis Stevenson, From Scotland to Silverado. Ed. James D. Hart (Harvard University Press, 1966).

Food for the Soul, if not the Body: Robert Louis Stevenson’s trip to California

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

One of the most beautiful and detailed travel accounts of a trip by railroad from the East to the West Coast in the nineteenth century was written by Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1879, the future author of Kidnapped and Treasure Island undertook his own adventurous voyage, from Scotland to San Francisco, in a romantic quest to join the lady of his dreams. Stevenson had met Fanny Osbourne in France and the two had fallen in love, despite obvious obstacles to the relationship – she was married, and ten years his senior. But when Stevenson received a letter from her

One of the most beautiful and detailed travel accounts of a trip by railroad from the East to the West Coast in the nineteenth century was written by Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1879, the future author of Kidnapped and Treasure Island undertook his own adventurous voyage, from Scotland to San Francisco, in a romantic quest to join the lady of his dreams. Stevenson had met Fanny Osbourne in France and the two had fallen in love, despite obvious obstacles to the relationship – she was married, and ten years his senior. But when Stevenson received a letter from her  indicating that she was about to be divorced, he decided to make the strenuous voyage to join her in California. His parents refused to pay, so he bought cheap passage on a boat to New Jersey and then a ticket on an “emigrant train” headed for the West Coast. By the time he reached America he was sick and exhausted. The remaining two-week trip to California almost killed him.

indicating that she was about to be divorced, he decided to make the strenuous voyage to join her in California. His parents refused to pay, so he bought cheap passage on a boat to New Jersey and then a ticket on an “emigrant train” headed for the West Coast. By the time he reached America he was sick and exhausted. The remaining two-week trip to California almost killed him.

Conditions on emigrant trains were difficult. The train made regular stops, three times a day, for food, but this meant that passengers had to rush to whatever eating establishment was closest to the train station and get back to the train car before it departed. Emigrant passengers were rarely given warning of the departing train. This meant that many often went without food, either from lack of money or lack of time.

But Stevenson, remarkably, does not dwell on the punishing conditions of his voyage. Each time he does mention a missed meal or a paltry choice of inedible food, he seems to follow with a description of something beautiful. After reporting a day passed with no food at all, he switches to a description of the amazing richness of place names in America, and how they provide a writer with food for the imagination. “None can care for literature in itself who do not take a special pleasure in the sound of names; and there is no part of the world where nomenclature is so rich, poetical, humorous, and picturesque as the United States of America … The names of the states and territories themselves form a chorus of sweet and most romantic vocables: Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, Florida, Dakota, Iowa, Wyoming, Minnesota, and the Carolinas; there are few poems with a nobler music for the ear.”

But Stevenson, remarkably, does not dwell on the punishing conditions of his voyage. Each time he does mention a missed meal or a paltry choice of inedible food, he seems to follow with a description of something beautiful. After reporting a day passed with no food at all, he switches to a description of the amazing richness of place names in America, and how they provide a writer with food for the imagination. “None can care for literature in itself who do not take a special pleasure in the sound of names; and there is no part of the world where nomenclature is so rich, poetical, humorous, and picturesque as the United States of America … The names of the states and territories themselves form a chorus of sweet and most romantic vocables: Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, Florida, Dakota, Iowa, Wyoming, Minnesota, and the Carolinas; there are few poems with a nobler music for the ear.”

The vast plains of Nebraska were the least able to offer nourishment for his thoughts. The unchanging dullness of this landscape overwhelmed him: “Our consciousness, by which we live, is itself but the creature of variety. Upon what food does it subsist in such a land? What livelihood can repay a human creature for a life spent in this huge sameness?”

At the end of his voyage, Stevenson tells an anecdote that seems to sum up the strange mixture of brutality and nourishing hope that he had come to see as characterizing the experience of a newcomer to America. Seated at the end of a stifling railcar, he had propped the door open with his leg to get some air. A newsboy, annoyed by the encumbrance, kicked him and repeatedly jostled him as he continued to pass back and forth. Robert was feverish, and depressed by the lack of civility. “But suddenly I felt a touch upon my shoulder, and a large juicy pear was put in my hand. It was the newsboy, who had observed that I was looking ill and so made me this present out of a tender heart.”

Fanny Osbourne later wrote that her lover arrived in California barely alive. But she was the prize that assured his survival. They were married in San Francisco in May 1880. The newlyweds spent the summer, while Robert recovered his health, in a cabin in the abandoned Silverado mining camp, on the slope of Mount St. Helena.

Fanny Osbourne later wrote that her lover arrived in California barely alive. But she was the prize that assured his survival. They were married in San Francisco in May 1880. The newlyweds spent the summer, while Robert recovered his health, in a cabin in the abandoned Silverado mining camp, on the slope of Mount St. Helena.

Thomas Hill, Mount St. Helena, Napa Valley

For Further Reading:

Robert Louis Stevenson, From Scotland to Silverado. Ed. James D. Hart (Harvard University Press, 1966).

What Women Know about Sex (and Eggs)

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

One of the best-known stories from the ancient Greek medical texts tells of a slave entertainer who became pregnant but didn’t know what to do about it. In one of the versions that survived, from the Hippocratic treatise On Generation/Nature of the Child, she realized she was pregnant and told her owner, who in turn called in the writer of the story, a physician.

How did the girl know she was pregnant? Other Greek texts say that women know because they feel a very special sensation, that of the mouth of the womb shutting. Here, though, we are told that the girl had heard other women say that you know you are pregnant because the man’s seed doesn’t run out after sex.

There’s a fascinating reference in this same treatise to the belief that a woman can choose to expel the seed emitted both by her and by her partner ‘when this is what the woman intends’. What is that about? And if it’s so easy, why didn’t the slave just expel the seed? Perhaps she tried, but failed. Or maybe she’d not heard about this technique.

The Lacedaimonian Leap

So what happened? What did the physician advise? Something that later historians have labeled ‘the Lacedaimonian leap’, a pleasingly alliterative name referencing Lacedaimonia, the area around ancient Sparta, and recalling ancient accounts of the women of Sparta as both athletic and independent. What this writer in fact suggests is that the girl should jump up and down with her heels touching her buttocks on each leap; after seven of these leaps (perhaps a significant total, in terms of beliefs about the power of certain numbers), the seed comes out with a noise, and has the appearance ‘as if someone had removed the external shell of a raw egg, and the fluid part inside was visible through the internal membrane’ (tr. Potter). In the middle there is something that appears to the writer to be an umbilical cord ‘and through this the movement of breath in and out first took place’.

Seeds and Eggs

The writer confidently describes this as a seed ‘on the sixth day’. Clearly, it isn’t. But the reference to an egg is really tantalizing. In ancient Greece, some writers thought that both men and women contributed ‘seed’ to make a baby; others thought that the man’s seed mixed with the raw material of the woman’s blood; and others seem to have thought that the man plants his seed in a woman’s body, without any female contribution other than the ‘soil’. Nobody talks about women having ‘eggs’. And of course this writer doesn’t, either; instead he draws an analogy with the gestation of a chick. Elsewhere in this treatise, he recommends looking at hen’s eggs, opening one per day to observe how the chick develops, because humans grow in just the same way, starting with a speck of blood which is the umbilicus, and then, through taking in ‘breath’, this speck inflating until it forms a recognizable living being.

And hens and women connect on a number of levels. The ancient Greek medical texts also describe how the process of labor is about the baby pecking its way out of the womb like a chick out of an egg. Here, the womb is passive, and there’s nothing for the woman giving birth to do except wait for the baby to work its way out. So human conception, gestation and birth all resemble those processes in hens. However, I don’t think there are any references to hens doing the ‘Lacedaimonian leap’, either with, or without, the seal of approval from a physician!

Reference:

Potter, Paul (transl.) Nature of the Child, Hippocrates, vol. X, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

August 7, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Westward Ho!

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Wonders & Marvels is headed West! We have just kicked off our Adventures in the American West series exploring the American frontier as it expanded ever westward over time. To celebrate this series, Cabinet of Curiosities is also exploring American frontiers.

Ever Westward We Go

Let’s go back to the very beginning, before America was even America. Everyone has heard of Christopher Columbus, but what about Francisco Hernandez? He may not be a household name, but Hernandez made important discoveries traveling Mexico in the 1570s and documenting thousands of new species. Learn all about Hernandez’ contributions to science and how Galileo himself helped rescue these discoveries from obscurity in the University of Oklahoma’s new exhibit “Galileo’s World“.

Let’s go back to the very beginning, before America was even America. Everyone has heard of Christopher Columbus, but what about Francisco Hernandez? He may not be a household name, but Hernandez made important discoveries traveling Mexico in the 1570s and documenting thousands of new species. Learn all about Hernandez’ contributions to science and how Galileo himself helped rescue these discoveries from obscurity in the University of Oklahoma’s new exhibit “Galileo’s World“.

When you imagine the American frontier, you don’t necessarily picture slaves. Yet, slavery was an important component of the frontier economy in places like Louisiana and Mississippi, which were once frontier states. In Slate’s fifth podcast from their History of American Slavery series, Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion explore so of the important slave uprisings real and imagined.

East Meets West

East Meets West

Which animal do you associate with the American West? Maybe the buffalo. How about the camel? That’s right, the camel generally associated with Africa and the Middle East was once considered the solution to settling the west. In 1855 Congress approved allocating $30,000 for the purchase of camels “to be employed for military purposes.” Whatever happened to this now obviously ill-fated plan? Check out the Smithsonian’s article on this surprising frontier settlement strategy.

What did explorers and adventures eat on the frontier during the Gold Rush? Sushi! Not just a modern fad, the sushi was an increasingly popular import after the Gold Rush sent Americans westward to seek their fortunes. An Eccentric Culinary History gives us the whole story about sushi’s arrival and increased popularity in the United States and the Great Sushi Craze of 1905.

What did explorers and adventures eat on the frontier during the Gold Rush? Sushi! Not just a modern fad, the sushi was an increasingly popular import after the Gold Rush sent Americans westward to seek their fortunes. An Eccentric Culinary History gives us the whole story about sushi’s arrival and increased popularity in the United States and the Great Sushi Craze of 1905.

Ready to explore more of the West? Take a look at these other posts from the series:

Rascals & Rogues & Oily Hucksters

August 6, 2015

Mark Twain’s Bloody Hoax

By Roy Morris, Jr. (Guest Contributor)

When Samuel Clemens arrived for his first day of work as a cub reporter on the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise in the autumn of 1862, veteran reporter Dan De Quille gave him a valuable piece of advice. “Get the facts first,” said Dan, “then you can distort them as much as you like.”

When Samuel Clemens arrived for his first day of work as a cub reporter on the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise in the autumn of 1862, veteran reporter Dan De Quille gave him a valuable piece of advice. “Get the facts first,” said Dan, “then you can distort them as much as you like.”

The neophyte young reporter took the advice to heart. After all, Dan De Quille had recently written a story about an unfortunate inventor who froze to death in Death Valley after his self-designed suit of “solar armor”—a sort of primitive portable air conditioner—had malfunctioned, leaving him covered with frost, a foot-long icicle hanging from his nose.

A few months later, under his new pen name, Mark Twain published an even grislier story about a local resident who, wrote Twain, went crazy one night and massacred his entire family. “Hopkins dashed into Carson [City] on horseback, with his throat cut from ear to ear, and bearing in his hand a reeking scalp from which the warm, smoking blood was still dripping,” Twain reported. “The long red hair of the scalp…marked it as that of Mrs. Hopkins.” The bodies of their six children were discovered butchered in their beds.

It was a terrible story, although not particularly rare in the West, where men and women routinely went on abrupt killing sprees after cracking under unendurable frontier hardships. There was only one problem—it wasn’t true. When readers pointed out that the Hopkinses were still walking around, hale and hearty, Twain published a follow-up story the next day in the Enterprise. It read, in full: “I take it all back.”

Roy Morris, Jr., is the editor of Military Heritage magazine and the author of five well-received books on the Civil War and post-Civil War era, including biographies of Walt Whitman and Ambrose Bierce. His latest book is Lighting Out for the Territory: How Samuel Clemens Headed West and Became Mark Twain . A former newspaper reporter himself, he resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

. A former newspaper reporter himself, he resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

IMAGE:The Virginia City Territorial Enterprise (seen in later years) was the best newspaper between St. Louis and San Francisco. Its young, rollicking staff quickly welcomed the neophyte Sam Clemens into its ranks. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in April 2010.