Holly Tucker's Blog, page 21

December 7, 2015

Anti-Vaxxers Railed against the First Smallpox Inoculations, 1800s

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Smallpox was a devastating epidemic until Edward Jenner realized that milkmaids were immune to the disease. The “father of immunology” theorized that cowpox, a similar but less virulent disease contracted from cows, protected the milkmaids from smallpox. His hypothesis was tested successfully in 1796 and vaccinations began soon thereafter.

But great controversy and fear swirled around inoculations with cowpox. Opponents of vaccination spread scare stories about Jenner’s method.

The most sensational claim was that the introduction of material from cattle into humans would cause people to develop bovine features. A famous cartoon titled “The Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation” by the satirist James Gillray was published by the Anti-Vaccine Society in 1802. The scene at London’s St Pancras Hospital depicts vaccinated men and women with horns erupting on their foreheads and bulls, cows, and calves bursting out of their mouths, eyes, ears, noses, arms, and buttocks. A painting on the wall shows the Israelites worshipping the Golden Calf.

Dr. Benjamin Moseley, Royal College of Physicians, issued lurid warnings implying that the cowpox vaccine contained bovine venereal disease. “Can any person say what may be the consequences of introducing the Lues Bovilla [syphilis of oxen], a bestial humour, into the human” body? In Moseley’s 1800 anti-vaccination tract he also alluded to ancient Greek mythology, namely the stories of Pasiphae and the Minotaur. Pasiphae was a queen of Crete who formed a perverse desire to mate with a bull. In the myth, Pasiphae’s lust was satisfied and she gave birth to a monstrous infant with a bull’s head and a human body–the Minotaur. An ancient Greek vase painting depicts Pasiphae holding the baby Minotaur on her lap; she looks reluctant to nurse her son.

“Who knows,” continued Moseley, but that “the human character may undergo strange mutations” replicating the nature of cattle? Moseley went on to suggest that a vaccinated lady risked becoming a “modern Pasiphae to rival the fables of old,” and warned of vaccinated women wandering in cow pastures hoping to have sex with bulls. Another physician, Dr. Thomas Rowley, went so far as to claim that an “ox-faced baby boy” had actually been born to a vaccinated woman. A cartoon showed an alternative shock scenario, a midwife presenting a newborn calf with a baby’s horned head to the vaccinated mother.

By the 1840s Jenner’s vaccine had become widely accepted and his work is often said to have saved the lives of more people than any other medical discovery.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014), shortlisted for the London Hellenic Prize.

December 3, 2015

Anesthesia: Who Knew What When?

By Sarah Alger

Accounts by patients of surgery before anesthesia are harrowing, to say the least. Reading one description by a man who underwent an amputation in 1843—a scant three years before the first successful public demonstration of anesthesia—I wondered how bitter it must have tasted for him and others who, after millennia with no anesthesia, missed it by a hair’s breadth in time, left to remember the horror for the rest of their lives.

It’s only with the benefit of hindsight that we can ask: The clues were copious—why weren’t they seized upon sooner?

In the 1840s, a Hartford dentist named Horace Wells experimented with nitrous oxide, having seen the gas used as a party drug in public halls and observed that pain was dulled under its influence. In 1845, he led a public demonstration on a dental patient, which failed for reasons unclear, as I described here.

Harvard chemist Charles T. Jackson.

Though Wells was discouraged, his young apprentice, William T.G. Morton, was undeterred. He chose to work with another drug popular at “frolics” of the time period: ether. Morton made the acquaintance of a Harvard chemistry professor named Charles T. Jackson, who suggested that he use a high grade of sulfuric ether. Jackson, who was also trained as a physician, appeared to know that ether could prove useful in surgery, but seems not to have acted on this knowledge.

On October 16, 1846, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Morton successfully administered ether to a surgical patient in a public demonstration. As acclaim was heaped upon Morton, Wells unsurprisingly cried foul—but so did Jackson. A bitter dispute rose all the way to Congress, which formally credited Morton.

This was not the first time Jackson sought credit for a discovery. Perhaps the most publicized was his claim to the telegraph. In 1832, aboard a packet ship from France to the United States, Jackson made the acquaintance of Samuel Morse. Though they did discuss the possible use of electricity in communication, the extent of Jackson’s contribution will never be known.

Jackson never ceded his claim to anesthesia; his gravestone reads: “Through his observations of the peculiar effects of sulphuric ether on the nerves of sensation, and his bold deduction therefrom, the benign discovery of painless surgery was made.”

Several years before the dispute over ether, a Georgia physician named Crawford Long had been using the drug in his practice, but apparently not knowing the gravity of discovery, did not speak up until after the Boston demonstration.

And some 40 years before him, renowned chemist and inventor Humphry Davy published a treatise on nitrous oxide, noting: “As nitrous oxide in its extensive operation appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place.”

December 2, 2015

Paris, A (Researcher’s) Love Story

By Rachel Mesch

It’s a scene any tourist will recognize: along the picturesque quais of the Seine, vendors with their green, rectangular boxes line the sidewalks, peddling colorful postcards and souvenirs, knick knacks and paintings, a little piece of Paris to bring home.

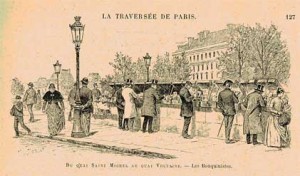

For the scholar, on the other hand, these traditional booksellers, with their used books and old magazines, offer a key to the past. The bouquinistes (pronounced boo-kee-neest), as they are known, bring our archives out of the dark quiet of rare book rooms and display them in the midst of the bustling Parisian cityscape. Without call numbers or catalogs, we weave through the thick rope of tourists and scan from stand to stand, looking for the telltale fraying leather covers of timeworn texts, or the mastheads of old newspapers and magazines.

For the scholar, on the other hand, these traditional booksellers, with their used books and old magazines, offer a key to the past. The bouquinistes (pronounced boo-kee-neest), as they are known, bring our archives out of the dark quiet of rare book rooms and display them in the midst of the bustling Parisian cityscape. Without call numbers or catalogs, we weave through the thick rope of tourists and scan from stand to stand, looking for the telltale fraying leather covers of timeworn texts, or the mastheads of old newspapers and magazines.

For the dix-neuviémiste, the scholar of nineteenth-century French literature, it is rare that a librarian at the Bibiliothèque Nationale de France will hand us an actual book t hese days.

hese days.

Nineteenth-century printers moved from using cotton and linen to wood pulp for their paper, and due to the high acidity of this new material, the pages of these books now crumble easily at the slightest touch. As a result, the national library has scanned these texts, and we are forced to read them through a screen. What a thrill, then, to find a long out of print nineteenth-century novel hidden on the shelf of the bouquiniste! For five, ten, fifteen Euros, one can carefully study an obscure text on the terrace of a neighboring café instead of the solitude of the microfilm chamber.

If the bouquinistes seem as old as Paris itself, it’s because they nearly are. Dating back to the sixteenth century, these vendors increased steadily over the periods that followed. During the French Revolution, they further multiplied, circulating high demand political brochures and newspapers; their numbers swelled again during the Paris Worlds Fairs, or Expositions Universelles, at the end of the nineteenth century, as millions thronged the city to see its new iron skyscraper. Now mini Eiffel towers populate the shelves of certain vendors alongside the used books, or bouquins, that they are named for, in standard sized wooden vestibules regulated by the government.

The bouquinistes of the Quai Saint Michel in the nineteenth century.

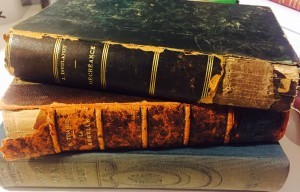

As a scholar trained in literary studies, encountering copies of books central to my research has been exhilarating, as it brings the notion of material culture to life. Holding an original copy of a book you are trying to situate historically and contextually puts you, quite literally, in touch with this very history and context. If you are lucky, the previous owner has left some trace of his or her presence–a signature, an oily fingerprint–a sign of the book having been owned, read, handled.

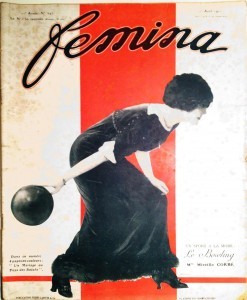

And then, if you are even luckier, you might fall in love. It was on the quais of the Seine that I first purchased a copy of Femina, the first photographic women’s magazine published in France. Launched in 1900 by entrepreneurial journalist Pierre Lafitte, who had an important intuition about female market share, the magazine was a cross between Vogue and Ladies Home Journal, consciously aimed at the Belle Epoque female reader who wanted to take on modern roles without abandoning her femininity.

And then, if you are even luckier, you might fall in love. It was on the quais of the Seine that I first purchased a copy of Femina, the first photographic women’s magazine published in France. Launched in 1900 by entrepreneurial journalist Pierre Lafitte, who had an important intuition about female market share, the magazine was a cross between Vogue and Ladies Home Journal, consciously aimed at the Belle Epoque female reader who wanted to take on modern roles without abandoning her femininity.

Shopping at the bouquinistes in 1900.

Eventually, in preparation for the book that I would write on the topic, I devoured the whole print run of Femina in bound library volumes and, yes, microfilm readers. But the project was launched by that first physical contact with someone’s old copy discovered in the shadows of a green wooden box. Excitement stirred in me as I thumbed through its outsize pages, with advertisements for hair products and furniture alongside gorgeous portraits of women writers (some of whose novels I had purchased previously from other bouquinistes…) and other women achieving in fabulous and daring new ways; more than a window onto a past era, the magazine offered direct contact, as I caught a weight loss advertisement slip from its pages, a card announcing an upcoming lecture, the occasional copy of a lithograph by a popular artist. Being able to buy my own copies of Femina not far from the kiosks where Parisian women would flock to purchase them in the 1900s set the project in motion from a place of passion and connection.

That place is Paris, where even research can be romantic. #LifeLoveParis

A selection from the author’s collection.

___

For a brief history of the bouquinistes, see “Histoire des bouquinistes des quais de la Seine” on Paris ZigZag. For a bit more detail, see the Bouquinistes de Paris’s own website.

To see how little has changed in the past century, check out these amazing images starting from 1900.

November 23, 2015

A Spy in the Spice Trade

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

You know the beginning of this story. In the fifteenth century, Portugal under the leadership of Prince Henry the Navigator (a misnomer applied to him by nineteenth century British historians for nineteenth century British reasons) began maritime exploration along the coast of Africa. More or less a hundred years later, a Portuguese fleet commanded by Vasco da Gama reached India. After a certain amount of bumbling around, Portugal transformed itself as a maritime empire with a lock on the spice trade.

You know the beginning of this story. In the fifteenth century, Portugal under the leadership of Prince Henry the Navigator (a misnomer applied to him by nineteenth century British historians for nineteenth century British reasons) began maritime exploration along the coast of Africa. More or less a hundred years later, a Portuguese fleet commanded by Vasco da Gama reached India. After a certain amount of bumbling around, Portugal transformed itself as a maritime empire with a lock on the spice trade.

For almost a hundred years, the Portuguese successfully protected their control over the sea routes to the Indian Ocean. Foreign ships caught sailing to the Indies were seized and their crews sentenced to a lifetime in the galleys. Suspected spies were arrested and shipped back to Lisbon for trial; those from the Protestant countries of England and the independent northern Netherlands were charged with heresy as well as espionage.*

Things changed in 1580, when Phillip II of Spain** conquered Portugal and united the two countries. The enemies of Spain became the enemies of Portugal, especially England and the Netherlands. The two Protestant countries could no longer buy spices from Portugal. Suddenly free trade was a religious as well as a political issue. The English took the direct approach and attacked Portuguese ships as they returned from the Indies. The Dutch preferred to trade rather than raid, but establishing trade with the Indies would require information they didn’t have.

Dutch merchants sent a spy overland to the Indies. Before he returned they received all the information they wanted from a source they didn’t expect: a Dutch spy who worked right under the nose of the Portuguese.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten was a Dutch Catholic, born in the Netherlands in 1563. When he was seventeen, he went to Lisbon to work for a merchant. In 1583, he traveled to Portugal as secretary to the new Archbishop of Goa, the Portuguese capital in India.

Linschoten worked in Goa from 1584 to 1589. As secretary to the Archbishop he had access to protected information regarding trade routes and sailing conditions. He questioned any European traveler who came through “golden Goa” about the countries further east. When the Archbishop died in 1589, Linschoten began a four-year-long voyage home to the Netherlands, learning even more about the Portuguese trading empire on the way.

Back in the Netherlands, Linschoten wrote Voyages to the East Indies, an account of everything Dutch merchants needed to know if they wanted to trade in the Indies. He described the sea routes to the east, including where to get fresh water and vegetables and what time of year the weather was best for safe sailing. He explained that they would need silver to buy spices because the Asians weren’t interested in European products. He described the countries and customs of Asia from India to Japan. He even provided up-to-date maps. Most important, Linschoten revealed that the once powerful Portuguese army, which had defended the trade routes with blazing guns in the past, was no longer so powerful. The sea routes to the east were open to anyone who dared take them.

In 1595, Dutch ships sailed for Java, with a copy of Linschoten’s Voyages aboard as a guide. Portuguese control of the spice trade was over.

*A serious matter in the days when the Spanish Inquisition was more than Monty Python routine.

**He’s the guy who was married to Queen Mary Tudor from 1554 until her death in 1558, tried unsuccessfully (and illegally) to marry her sister, Queen Elizabeth II, and sent the equally unsuccessful Spanish Armada against England in 1588. He was also one of the most powerful rulers in Europe at the time.

November 17, 2015

The FBI Investigates a Case of “Spontaneous Human Combustion”

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

During the summer of 1951, the St. Petersburg (Florida) Police Department needed help. On July 2, 67-year-old woman named Mary Hardy Reeser had burned to death in her apartment, and the police did not know how or why. A fire of unknown origin had reduced her body to fine ashes — except for her skull (“shrunken to the size of a teacup”), a small section of backbone, and her left foot, which still wore a shoe.  A chair, end table, and small rug had been incinerated, and the ceiling was darkened by smoke, but otherwise the apartment appeared little affected by the intense heat necessary to transform a human body into cremains.

A chair, end table, and small rug had been incinerated, and the ceiling was darkened by smoke, but otherwise the apartment appeared little affected by the intense heat necessary to transform a human body into cremains.

Stalled in his department’s investigation, police chief J.R. Reichert asked for the FBI’s help and shipped to Washington several pieces of evidence, including clothing fibers, glass fragments found in Reeser’s ashes, particles of her bones, an unburned section of the rug (“heavily soaked with greasy substance”), chair springs, and the shoe. He asked the FBI to investigate these items and to provide “any information or theories that could explain how a human body could be so destroyed and the fire confined to such a small area and so little damage done to the structure of the building and the furniture in the room not even scorched or damaged by smoke.”

Many people had speculated that Reeser’s death was an example of spontaneous human combustion (SHC), a phenomenon that had occurred in novels of Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, and Frederick Marryat, and also in unverified factual cases around the world in which people appeared to have caught fire without a known source of ignition. Could SHC explain Reeser’s fiery death?

The FBI scrutinized the evidence and thought not. Its analysts speculated that an outside source, such as a burning chair or clothing, had set Reeser aflame. “Once the body starts to burn there is enough fat and other inflammable substances to permit varying amounts of destruction to take place,” the FBI noted. “Sometimes this destruction by burning will proceed to a degree which results in almost complete combustion of the body.” The heat from the burning body rises, possibly leaving intact most of the smoldering fire’s surroundings.

The Reeser case continued to receive press attention for years, and citizens sent to the police and FBI their own theories on her death. These attributed the cause of the deadly fire to the use of an oxy-acetylene torch, a murderer who cremated Reeser elsewhere but moved her remains back to her apartment, a form of cancer that creates high temperatures in the body, and of course SHC, among other speculations.

The St. Petersburg Police concluded that Reeser had fallen asleep while smoking, accidentally igniting her rayon nightgown and the chair on which she was sitting. They closed the case soon after receiving the FBI analysis.

Further reading:

The FBI’s file on the Reeser case.

Nickels, Joe; Fischer, John F. (March 1984). “Spontaneous Human Combustion.” The Fire and Arson Investigator 34 (3).

November 16, 2015

Two Sisters at Waterloo, June 1815

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

I have been spending the last few weeks working at the wonderful Chawton House Library in Hampshire, England, exploring their collection of women’s travel narratives from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of these that most amazed me is by Charlotte Waldie Eaton, originally published anonymously, in 1815. In June of that year the young Charlotte, age 26, and her sister Jane, age 21, were visiting Belgium with their brother. Charlotte was an aspiring writer. Jane was a painter. Both were enjoying a trip that they hoped would inspire them to produce interesting accounts and sketches of their travels.

The little party arrived in Brussels on June 15. The city was exciting, filled with international travellers and soldiers on leave. Charlotte wrote that “There could not be a more animated and holiday scene; everything looked gay and festive, and everything spoke of hope, confidence, and busy expectation.” After settling into a hotel on the Place Royale, they spent the rest of the day visiting the sights. The city was the temporary headquarters for the Duke of Wellington and his army, who were anticipating a confrontation with Napoleon somewhere in France in the coming weeks.

But Napoleon had moved northward from Elba much more quickly than the English had anticipated. In the middle of the night Charlotte and Jane were awakened by bugles sounding in the streets. “Is that a call to arms?” Charlotte exclaimed, and both sisters laughed excitedly. Then came the drums and the Highland bagpipes. The Place Royale was suddenly filled with “officers looking in vain for their servants, servants running in pursuit of their masters, baggage wagons loading, trains of artillery harnessing.” Word came that the French army was advancing on Brussels. Within hours, explosions could be heard that told them a battle was taking place just a few miles from the city. “We listened in a state of terrible uncertainly and suspense, and thought with horror, in the roar of every cannon, that our brave countrymen were every moment falling in agony and death.” Going into the streets, the young women were greeted by riders coming back from the direction of the battle, each one with a report of events that contradicted the last. “Nobody could tell us where our army was engaged, nor under what circumstances, nor against what force …”. The confusion was absolute, while the sound of cannon fire continued unabated. By the time the sisters and their brother decided that they should flee the city, it was impossible to find horses and a carriage. Wagon loads of wounded began to arrive. Charlotte felt sick as she watched. Their little group finally managed to find a carriage that could take them away from the city. They left, still not knowing if the English had lost the battle and if the French army was moving in behind them. “All Brussels seemed to be running away.” Bloodied soldiers were everywhere on the road, moving in both directions. They took two of the most severely wounded into their carriage, and headed for Antwerp.

Wagon loads of wounded began to arrive. Charlotte felt sick as she watched. Their little group finally managed to find a carriage that could take them away from the city. They left, still not knowing if the English had lost the battle and if the French army was moving in behind them. “All Brussels seemed to be running away.” Bloodied soldiers were everywhere on the road, moving in both directions. They took two of the most severely wounded into their carriage, and headed for Antwerp.

There they joined a city full of fugitives and waited desperately for reliable news of the battle. When at last the news came directly from the front that the French had been defeated, Charlotte was ecstatic. But at the same time the horror of the fighting was only becoming worse for her and others who had watched from a distance. The siblings stayed in the city as the cartloads of dead and wounded poured in. Charlotte reports on horrifying interviews with survivors, including an 18-year-old boy returned from the battlefield, who had just had the “soul-harrowing experience” of searching among the dead bodies for a lost friend. She learns the truth of the crushing defeat of the French, hears the speculation about numbers of dead on both sides, comments on the inability of military reports to capture the awful reality of forty-two thousand lives lost and many more destroyed. “Of 130, 000 Frenchmen who had marched yesterday morning to battle, flushed with all the hopes and confidence of victory, no trace, no vestige now remained; they were all swept away; they were scattered by the whirlwind of war over the face of the earth.”

On July 15, one month later, Charlotte and Jane returned with their brother to Brussels and visited the field of Waterloo. The stench of corpses and putrifying limbs was still in the air. “The road between Waterloo and Brussels was one long interrupted charnel-house: the smell, the whole way through the forest, was extremely offensive, and in some places scarcely bearable. Deep stagnant pools of red water, mingled with mortal remains, betrayed the spot where the bodies of men and horses had mingled in death. “ Arriving at the field itself, they stared in shock at endless rows of freshly dug graves. The women left their carriage and walked on the grass, trying to reconstruct the battle manoeuvers as they had heard of them, and trying to bear the horrible spectacle of hastily dug pits with pieces of bone and flesh still exposed to the air. “The whole field was literally covered with soldiers’ caps, gloves, belts, shoes, and scabbards. Broken feathers battered into the mud, remnants of tattered scarlet or blue cloth, bits of fur and leather, black stocks and havresacs, buckles, packs of cards, books, and innumerable papers of every description …”

From one of the graves Charlotte writes, “I gathered the little wild blue flower known by the sentimental name of “Forget me not!” which to a Romantic imagination might have furnished a fruitful subject for poetic reverie or pensive reflection.” Jane, meanwhile, sat down to sketch. What she produced to accompany her sister’s narrative is a stunning panorama of the landscape. But it is cleansed of all visible sign of violence. It is reproduced in the book as a wide fold-out.

(Photo courtesy Chawton House Library)

(Photo courtesy Chawton House Library)

This is not the battlefield as the two sisters actually saw it, covered with refuse and human remains. It is how the poet Byron would see it, when he visited Waterloo in May of 1816. Perhaps he had read Charlotte’s description and seen Jane’s illustration of the place, so ‘fruitful for a Romantic imagination’. He does not describe the field as a grand scene of battle, as many other artists by then had depicted it. His description, in canto 3 of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, is of a place of beauty, sadness, and monstrous waste:

As the ground was before, thus let it be; –

How that red rain hath made the harvest grow!

And is this all the world has gained by thee,

Thou first and last of fields! king-making Victory?

For further reading:

Charlotte Anne (Waldie) Eaton, The Battle of Waterloo … By A Near Observer. Edinburgh: John Booth, 1816 (9th Edition).

November 13, 2015

Presto! Colored Eggs and Hidden Hens in Molecular Gastronomy

When a dish produced by molecular gastronomy arrives at the table, the atmosphere of attention, expectation, and surprise rivals that of when a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat. The most exciting culinary trend of the 2000s showcases chefs well known by enthusiasts of the likes of Ferran Adrià, Heston Blumenthal, and Grant Achatz of Chicago’s Alinea restaurant. But what’s behind the molecular magic?

The preparation of the plates is at once scientific, architectural, often jaw-droppingly beautiful, and completely improbable. Foams, spheres, gels, and gases take food presentation to new levels as chefs combine succulent ingredients with scientific method and equipment, using dehydrators, sous-vides, centrifuges, enzymes, emulsifiers, and protein binders to sculpt foods and transform flavors.

Notwithstanding the glitz, molecular gastronomy has been met with some pushback from food purists like Alice Waters of the Slow Food movement. Waters, advocating for simple, natural ingredients and traditional techniques, has referred to molecular chefs as “mad scientists.” But Hervé This, the father of the molecular gastronomy in France, points out that there is really nothing new or unnatural about their preparations. Bringing science into the culinary tradition has existed since nineteenth-century French author Brillat-Savarin advocated for the use of physics and chemistry in the kitchen. Moreover, in some ways, molecular gastronomy is more natural than anything else, since it is premised on understanding and respecting the (natural) laws of science.

Besides, as its proponents never fail to claim, the food is just better. Knowing, for example, the exact temperature at which proteins denature, allows for making the juiciest, most tender meat. And there is safety: you wouldn’t feel comfortable crossing a bridge that engineers hadn’t inspected. Why is it not better to have a chef who understands the scientific principles of cooking making your food?

But even if the flavors are fabulous, the appearance awesome, and the science sound, questions persist. Molecular gastronomy, seen from its worst angle, has been termed misogynist, elitist, and anthropocentric. Harvard Science and Technology scholar, Sophia Roosth has pointed out that molecular gastronomy, whose chefs are mostly men, tend to rethink the same recipes that women have been making successfully for generations (such as the simple pot roast), correcting these women and their methods with science. The subtext is: It took a man armed with reason to correct the follies of women, even in the kitchen.

In terms of class, issues of accessibility have been raised. Any aspiring cook can use Alice Waters’s cookbook to turn out a dish bearing at least a distant resemblance to those in her San Francisco restaurant Chez Panisse. But often times the cost of equipment used by molecular gastronomy chefs, much like the price of eating in their restaurants, amounts to hundreds, if not thousands of dollars. Not exactly democratic eating.

Lastly, but perhaps not least, when the rabbit is pulled from the hat and appears on the plate, eaters are so impressed with the magic they sometimes forget to ask about the rabbit. The energy and confidence of the best scientist-chefs is infectious, but critics argue that the prestidigitations of the laboratory sometimes elide the natural world. In his book, Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor (Columbia University, 2008), Hervé This gets granular on cooking the perfect hard-boiled egg. He writes about time, temperature, egg verticality versus horizontality, lipids, proteins, and so on. Nowhere in his instructions, however, does he stress the importance of where the egg was sourced, how the chicken was treated, and what it ate before laying the egg.

Yet, surely the nature of the proteins in the food consumed by the hen on the farm is as important and relevant as the temperature at which the chef denatures them in the kitchen…

“Of Foams and formalisms: Scientific Expertise and Craft Practice in Molecular Gastronomy,” American Anthropologist, Vol. 115, No. 1, pp. 4-16, 2013.

November 12, 2015

Before Pepper Spray: The First Crowd-Control Weapons

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Have you ever been pepper-sprayed or tear-gassed? You can create the experience on a small scale by frying fiery-hot jalapeños in oil and then fleeing your smoke-filled kitchen. Oleoresin capsicum inflames eyes, nose, and throat, causing searing pain, restricted airways, and temporary blindness. Tear gas, a volatile solvent invented in the 1920s, has the same incapacitating effects. These two “non-lethal” chemical agents wielded for crowd control are both prohibited in warfare by the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention.

Have you ever been pepper-sprayed or tear-gassed? You can create the experience on a small scale by frying fiery-hot jalapeños in oil and then fleeing your smoke-filled kitchen. Oleoresin capsicum inflames eyes, nose, and throat, causing searing pain, restricted airways, and temporary blindness. Tear gas, a volatile solvent invented in the 1920s, has the same incapacitating effects. These two “non-lethal” chemical agents wielded for crowd control are both prohibited in warfare by the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention.

As our stovetop experiment demonstrates, the ability to create a choking cloud of smoke is available to anyone with access to chilis scoring high on the Scoville Heat Index (units measuring Capsicum fire power). Imported from the New World to Asia by the Spanish, hot peppers became indispensable to local cuisines. But peppers could also be weaponized, as the Conquistadors learned. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Caribbeans and Brazilians set fire to hot pepper seeds and let the wind envelop their enemies in clouds of pungent smoke.

Asphyxiating chemical fumes were devised in antiquity, anticipating pepper spray and tear gas by 2,500 years. The Spartans deployed deadly sulfur dioxide gas in 429 BC. In 80 BC, the Roman commander Sertorius defeated rebels holed up in impregnable limestone caverns with an ancient version of tear gas. Noticing that his horse kicked up clouds of caustic lime dust, Sertorius piled up heaps of the white powder in front of the caves. As the prevailing north wind gathered force, the Romans stirred the mounds, raising great clouds that blew directly into the caves. Like tear gas, limestone or gypsum dust becomes extremely corrosive on contact with moist mucus membranes. The rebels surrendered.

A peasant revolt in China was suppressed in AD 178 with the same chemical agent, now delivered by new technology. The emperors’ forces manned “lime chariots” equipped with bellows to blast caustic lime powder “according to the wind” into the crowds of protestors.

All three ancient examples depended on friendly winds to avoid blowback, a perpetual problem for those who resort to biochemical weapons. Before the invention of gas masks, kerchiefs soaked in vinegar neutralized noxious fumes, an ancient technique still used by experienced demonstrators facing tear gas and pepper spray today.

November 9, 2015

Constipation in History

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

Feces are in the news again, with a further story pointing to the potential benefits of fecal transplants in a range of bowel conditions. The internet includes DIY advice along with suggestions of banking our own poo so that we can reboot our digestive system from it if anything goes wrong.

Feces are in the news again, with a further story pointing to the potential benefits of fecal transplants in a range of bowel conditions. The internet includes DIY advice along with suggestions of banking our own poo so that we can reboot our digestive system from it if anything goes wrong.

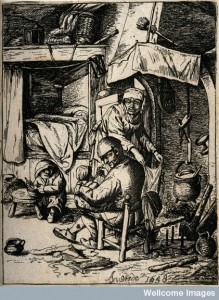

Examining the patient’s bodily products, as in this 1826 image, has long been a part of medicine. But that’s examining, not inserting. As I’ve explained elsewhere, when it came to animal excrement, ancient Greek and Roman medicine was pretty relaxed about its possible curative powers, although Galen notoriously offered a remedy for white odor-free dog dung suitable for those of a nervous disposition. In the history of medicine, poo has been just one of the wide range of possible substances that can effect change in the body.

The importance of ‘being regular’

But what if it’s producing the poo that is itself the problem? When I was working on women’s diseases in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I came across some extreme expressions of the view that constipation is the root of all evil. Like menstrual retention, it was thought to show weak muscles or ‘sluggishness’: like menstrual blood or semen which, if kept in the body, Galen thought were like snake venom, stale feces were also thought to act as a poison. If in doubt, get it out.

Ever since the time of Galen, excretion has been seen as one of the aspects of the body requiring careful control to safeguard health, but James Whorton suggested in his 2002 book, Inner Hygiene, that from the mid-nineteenth century improvements in public health and the rise of the factory led to an increased medical concern with the body’s own waste disposal system.

Auto-intoxication?

By around 1900–20, medicine had gone further in its ideas of poison in the body and had come up with the theory of ‘auto-intoxication’, leading to an absolute obsession with avoiding constipation. A key figure here was the late-nineteenth century figure, Sir Andrew Clark, who had suggested that ‘auto-intoxication by faecal products’ would cause bad breath, irregular appetite, wind and pain. Never one to mince his words, in 1887 Clark described ‘the faeces, usually scanty, hard, dark, and lumpy, occasionally consist of showers of scybalous masses, embedded in an offensive mucus swarming with bacteria’. Yuk! And, for Clark, that response forms part of the problem.

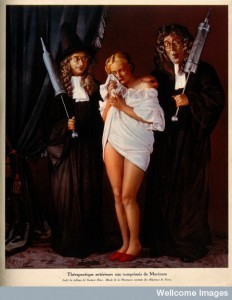

A scared beautiful young woman standing between two physicians holding clysters illustrating a treatment for constipation.

He argued that women’s constipation was likely to be worse because their sense of modesty meant they ignored the urge to open their bowels. Other physicians of the day thought that women were more likely to suffer because of a more sedentary lifestyle, or because of wearing corsets which, they thought, put pressure on the colon and made it sluggish.

So older themes, such as the weakness of the female sex, their vanity, and their coquetry, were implicated in constipation too. Alongside these traditions, the medical enemies of constipation came up with some new, and extreme, treatments that make fecal transplant sound relatively pleasant. In 1909 Arbuthnot Lane recommended removing the colon as the cure for constipation and all its attendant ills. That seems to be a step too far.

References

Clark, Sir Andrew (1887) ‘Observations on the anaemia or chlorosis of girls, occurring more commonly between the advent of menstruation and the consummation of womanhood’, Proceedings of the Medical Society of London 11, 55–66

Lane, Sir William Arbuthnot (1909) The Operative Treatment of Chronic Constipation, London: James Nisbet & Co.

Whorton, James C. (2000) Inner Hygiene: Constipation and the pursuit of health in modern society, New York: Oxford University Press.

November 5, 2015

The Unmanly Art of Breastfeeding in the Eighteenth Century

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

What if men could breastfeed?

There have certainly been medical cases of lactating men, such as when an illness causes a hormonal imbalance. Men do, after all, have the necessary equipment and with the right hormones, it could happen. It’s possible, if difficult, to induce lactation in adoptive mothers, so in theory, a nurturing father might be turned into a nursing father. Stranger things have happened. Even today, we hear occasional tales about fathers nursing infants after the mother has died, usually in desperation to comfort the crying child.

Portrait of Bishop Robert Clayton (1695-1758) with his wife Katherine. c. 1740. James Latham. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A letter by the Bishop of Cork to the Earl of Egmont was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1739-41). In the letter, the Bishop described his recent strange encounter with a seventy-year-old man who claimed that he had breastfed his child.

The tale begins when the Bishop was approached on his doorstep in Inishannon by the elderly man, a French Protestant refugee (Huguenot). The Huguenot had worked industriously, “by all accounts”, as a gardener until age “deprived [him] of his Strength ”. After the Bishop gave him half a Crown, the man left and the Bishop returned into the house.

Soon after, he “heard a Noise at the Door”. Apparently “out of Gratitude”, the Huguenot had returned to show him a curiosity: his own breasts, which he had used to suckle his child. The Bishop was sceptical, thinking that this was a ploy to obtain more money, but the physical evidence intrigued him.

According to the man, hist wife had

died when the Child was about Two Months old: The Child crying exceedingly while it was in Bed with him, he gave it his Breast to suck, only with an Expectation to keep it quiet; but, behold, he found that the Child in time extracted Milk; and he affirmed, that he had Milk enough afterwards to rear the Child.

The Bishop examined the old man’s breasts, which were unusually large for a man. The nipples, even more impressively, “was as larger or larger than any Woman’s I ever saw.” Unfortunately, this is all we know, because

Some Ladies were then passing by; so I sent him off in Haste, and have not seen him since.

I picture, here, a rather flustered Bishop shooing away the elderly beggar, panicked at the thought of being caught out closely examining another man’s nude chest–even if there was even a long religious tradition that depicted Jesus as a nursing mother. Curiosity and respectability were not always happy companions.

But I could not help comparing the Bishop’s anxious reaction to other instances of extraordinary breastfeeders, including aged grandmothers. It was certainly acceptable for eighteenth-century women to expose their lactating breasts in public, even breastfeeding grandmothers. For example, one sixty-eight-year-old woman who breastfed her grandchildren had such a quantity of milk “that, to convince the Unbelieving, she would frequetly spout it above a Yard from her” (Philosophical Transactions, 1739).

Gloria Steinem once wondered what the world would be like “If men could menstruate”. Steinem argued that menstruation would suddenly become a mark of male superiority: “[w]hatever a ‘superior’ group has will be used to justify its superiority, and whatever the ‘inferior’ group has will be use to justify its plight.” This certainly holds true—at least a bit—for early modern men who were seen as having menstrual-like flows: haemorrhoids or other regular bleeding. Such a flow did not undermine male authority and, in fact, could be a cultural marker of positive qualities, such as wealth and learnedness.

A father feeding his infant whilst the mother attends to domestic jobs and a small child plays with its food. Etching after A. van Ostade, 1648. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Male lactation… well, that was a bit more problematic. Menstrual-like flows might happen to many men (particularly those who indulged too much in the good life), but male breastfeeding remained uncommon. The Huguenot used to be a good father and hard worker, but his masculine status was complicated by his old age, foreigness and dependency. All of these categories undermined his manhood. Only certain types of male bodies could take on feminine characteristics without undermining manliness—and the Huguenot’s was not one of them.

If (all) men could breastfeed, lactating would be a (slightly damp) badge of superiority. But when (only some) men could breastfeed, it remained a curiosity and unmanly.

For the Bishop, examining another man’s nipples–particularly when they were no longer even producing milk–must have been uncomfortably intimate. No wonder the Bishop’s instinct was to send the Huguenot away… probably, no doubt with some version of “cover up, love” or “put them away, dearie” upon his lips.

Lisa Smith is a Lecturer in Digital History at the University of Essex. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800), as well as teaches a course on “Defining Boundaries: Natural and Supernatural Worlds in Early Modern Europe”. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. Follow her on Twitter, where she tweets as @historybeagle.