Holly Tucker's Blog, page 24

September 11, 2015

Are You an Opsophagist? Ruminating on Ancient Greek Table Ethics

By Thomas Parker (Regular Contributor)

Do you feel real resentment when somebody takes a bite of your sandwich and surgically removes the meat? Or are you the meat remover? Why is it bad form to eat cheese without bread in France? Is it just a question of taste or is more at stake?

If Plato and the Ancient Greeks were to chime in, they would make these ethical questions. We distinguish simply between the categories of “food” and “drink,” but the Ancient Greeks had three categories: sitos, opson, and oinos. The first, sitos, was the staple. It was usually bread made from wheat, but sitos could consist of barley or other grains, beans, or pulses. The second, opson, was the relish. It was typically meat, fish, or cheese, but it could be anything that flavored the sitos. The third, oinos, was wine.

Meat was the most prestigious opson, but was relatively rare in antiquity. Meat eating was special. It was highly ritualized, and always preceded by sacrificing a part of the animal to the gods. In general, meat was consumed more by the wealthy, and thought most fitting for heroes, warriors, and athletes, establishing food-based class and gender hierarchies early on.

Conversely, eating meat was also the sign of the barbarian. He shared with the hero a prodigious consumption, but was imagined showing his savagery by eating meat like an animal, usually raw with reckless abandon. Fish, though not a ceremonial food, became the opson most associated with conspicuous consumption, enjoyed by wealthy gourmets and gourmands.

Yet, sitos-based society was not as virtuous and democratic as it might sound- at least not by our modern standards. The ancients possessed a grain hierarchy that placed wheat on the top. Gluten was one key to wheat’s prestige. It provided structure and facilitated the wondrous form and fluffy texture. Barley did not have the leavening power of wheat, and was more flat.

The texture and color counted too. More highly processed white bread—the lighter, the better— was generally held in higher esteem than coarser dark breads, mashes or porridges. The Roman physician Galen categorized black breads as “dirty,” noting that they were typically consumed by the poor.

Sitos set itself apart from opson in other ways. Ovens and mills were necessary for bread. Fields had to be plowed and tended, and bread required an elaborate infrastructure premised on set methods and stability. So much was this the case that the “milled life” came to mean “civilized order” in Greek.

But that “civilized order” was also labor intensive. So much so that it subordinated women and slaves to complete the disproportionate amount of work it brought with it. Indeed, women’s identities became so rooted in cereal production that ancient marriage ritual reinforced the role of women as the processors of grain (Wilkins and Hill, 2006, 118). Though agriculturalists pointedly derided the less advanced pastoralists, hunters, and fisherman who lived more on opson, sitos ultimately encouraged inequity and the need for forced labor in ways primitive opson eaters did not.

September 9, 2015

Museum Mysteries: The Missing Cornerstone

By Sarah Alger (Regular Contributor)

“When in distress, every man becomes our neighbour.” So wrote Drs. James Jackson and John Collins Warren in a letter they circulated to their Beacon Hill community in 1810. The physicians’ aim: to build a general hospital for Boston. They sought to appeal to wealthy citizens’ charitable nature (hence this line, still often quoted here at Massachusetts General Hospital) and to their pragmatism in building a world-class city: Harvard Medical School needed a place for students to train.

“When in distress, every man becomes our neighbour.” So wrote Drs. James Jackson and John Collins Warren in a letter they circulated to their Beacon Hill community in 1810. The physicians’ aim: to build a general hospital for Boston. They sought to appeal to wealthy citizens’ charitable nature (hence this line, still often quoted here at Massachusetts General Hospital) and to their pragmatism in building a world-class city: Harvard Medical School needed a place for students to train.

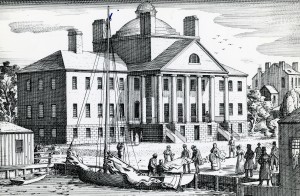

In 1811, the Massachusetts legislature granted a charter for what would become Massachusetts General Hospital (also the McLean Asylum). The following year’s eponymous war marked a slowdown in fundraising, but progress was made. A prime plot of land, Prince’s Pasture (so named not for royalty, but a surname of Prince) was found right next to the Charles River, so that patients could access the hospital both by land and water. The architect Charles Bulfinch, who had already designed the Massachusetts State House, was retained to create a building of granite. State Prison inmates got to work hammering the stone.

It was not until July 4, 1818, that the cornerstone of the building was laid. Under the stone were placed coins and a silver tablet with an inscription, and the ceremony was conducted with Masonic pageantry by the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. Grand Master Francis J. Oliver, addressing the master builder, noted: “…this building is not to be a temporary pavilion for the display of opulence, splendor, and pride, but a temple dedicated to humanity, a lazar-house built by enlightened Compassion, where CHARITY and PHILOSOPHY are to walk a perpetual round to alleviate misery, and to combat with and destroy disease and pain.”

Over the next few years, what rose from the spot was an imposing four-story Greek Revival building, topped by a dome. In 1821, the hospital was finally ready to receive patients. Who was the first to set foot in this temple dedicated to humanity? A saddler with syphilis (which he had contracted in New York, the record notes).

Now, 197 years later, space is at an extreme premium; nearly every inch of Prince’s Pasture has been built upon, and Bulfinch’s creation is surrounded by taller buildings. Both of the Bulfinch Building’s wings were extended, and the back of the building is now hemmed in by other structures.

No records exist to tell us the exact location of the cornerstone, so lavishly dedicated in 1818. Were those present that day to see what has grown up around it, no doubt they would marvel at the sight.

September 7, 2015

King George V’s Parrot

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

George V (1865-1936) owned an African grey parrot from the Congo named Charlotte. George obtained her in Port Said, Egypt, when he was a young midshipman in the Royal Navy in the 1880s (although some say Charlotte was a pink-grey parrot and a gift from his sister Victoria). Charlotte attended the king’s Privy Council meetings. Perched on His Majesty’s shoulder as he read through the royal “red boxes,” the parrot cast a critical eye over state papers and confidential documents, shouting “What about it?” in a stentorious voice.

When the king fell seriously ill, Charlotte spent hours pacing and muttering “Where’s the Captain?” During his convalescence, she was the first visitor the king requested. Charlotte flew to his shoulder and danced and bobbed, exclaiming “Bless my buttons! Bless my buttons! All’s well!”

African greys are very intelligent, easily bored, and can be known for behavioral problems. By all reports, Queen Mary despised the bird (she also loathed pigeons–filthy “rats with wings” she called them). But Charlotte’s only documented misbehavior was to make breakfasting with the king a bit stressful for guests. She insisted on digging heartily into everyone’s boiled eggs. Raw eggs are harmful for parrots but hard-boiled or poached eggs provide a treat. The eggshells and crumbs she scattered across the tablecloth were swiftly hidden from the queen’s notice by George, who would discreetly slide plates over them.

A photo of about 1930 shows the king’s grand-daughter Princess Elizabeth, about 4 years old, chasing Charlotte on the gravel drive, while Queen Mary, a Cairn Terrier, and a butler look on.

About the author: A research scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

September 3, 2015

Why I Fell In Love With Sarah Royce, Pioneer Woman of the Gold Rush

By Steve Boggan (Guest Contributor)

One of the great legacies of the 1849 Gold Rush is that many personal accounts of wondrous journeys and fabulous gold finds have survived, but nearly all of them were penned by men.

The exception that stands head and shoulders above many of these in its evocation of courage, fortitude and compassion was written by Sarah Royce, a young woman whose life was turned upside down the day her husband, Josiah, announced they were headed for the California gold fields.

One moment she was a homemaker raising a two year old daughter, Mary, the next she was waving goodbye to her farm in Iowa and heading west with tens of thousands of other hopefuls. And while the prospect was thrilling, it was also frightening – Sarah had never camped out before.

‘No house was in sight,’ she wrote as darkness fell at the end of her first day on the road. ‘Why did I look for one? I knew we were to camp; but surely there would be a few trees or a sheltering hillside against which to place our wagon? No, only the level prairie stretched on each side of the way. ‘

‘No house was in sight,’ she wrote as darkness fell at the end of her first day on the road. ‘Why did I look for one? I knew we were to camp; but surely there would be a few trees or a sheltering hillside against which to place our wagon? No, only the level prairie stretched on each side of the way. ‘

The overland 49ers took variations of what became known as the Oregon-California Trail, which wound through what today we call Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Oregon and Nevada. This took the travellers over swamp and river, desert and mountain, and to make it into California, you had to cross the Sierra Nevada Mountains before winter set in.

The Royces set off dangerously late and found themselves in a race to cross Forty Mile Desert in Nevada – the last obstacle before the mountains – before it was too late. They took advice from a fellow traveller on where to find water before embarking on the deadly 40-mile trek – but they missed a turning and were forced to turn back; if they couldn’t find this water they would die.

‘Turn back!’ wrote Sarah. ‘What a chill the words sent through one. Turn back, on a journey like that; in which every mile had been gained by most earnest labour, growing more and more intense, until, of late, it had seemed that the certainty of advance with every step, was all that made the next step possible.’

The Royces found their water and, with the help of some US soldiers sent to help stragglers like them, they made it over the Sierra by the skin of their teeth on October 19 1849.

The Royces found their water and, with the help of some US soldiers sent to help stragglers like them, they made it over the Sierra by the skin of their teeth on October 19 1849.

The first gold camp they settled in was in Weaverville, west of Redding, but after failing at prospecting, she and Josiah set up a makeshift store. Describing their customers, she wrote: ‘The majority of them were men of ordinary intelligence, evidently accustomed to life in an orderly community where morality and religion bore sway.

‘They very generally showed a consciousness of being somewhat the worse for a long, rough journey, in which they had lived semi-barbarous lives, and for their continued separation from the amenities and refinements of home.

‘But, mingled with these better sorts of men who formed the majority, were others of a different class – roughly-reared frontier-men almost as ignorant of civilised life as savages. Reckless bravados, even when under the restraints imposed by policy.’

Sarah and Josiah flitted from gold find to gold find for five years before settling in Grass Valley, not with a makeshift tent for a home, but in a proper house. Her strength and fortitude had kept her family safe and over the years she brought up four children as well-educated and staunch Christians.

Number 207 Mill Street, Grass Valley, where the Royces used to live, is now a municipal library named the Royce Branch after their son, Josiah Jr, who went on to become a renowned scholar and one of the greatest philosophers of his day.

Sarah died fulfilled and happy in 1891.

Steve Boggan is an investigative journalist and the author of GOLD FEVER: One Man’s Adventures on the Trail of the Gold Rush. He lives in London.

Steve Boggan is an investigative journalist and the author of GOLD FEVER: One Man’s Adventures on the Trail of the Gold Rush. He lives in London.

September 2, 2015

Clothes Make the (Wo)man? Pants Permits in Nineteenth-Century Paris

By Rachel Mesch (Regular Contributor)

On November 7, 1800, the prefecture of police for the city of Paris issued an order prohibiting women from wearing men’s clothing in public. Noting that many women cross-dress but not for (excusable) health-related reasons, and that this behavior was a danger to themselves and others, the city order declared that “any woman who wishes to dress as a man,” (toute femme désirant s’habiller en homme) must present herself to the prefecture for authorization. In order to do so, she would need the notarized signature of a health official declaring the medical necessity of this change in wardrobe—the only accepted criteria for such permission—as well as signatures of government officials. Henceforth, any cross-dressing women without proper documentation risked being arrested.

This law remained in effect in Paris for 213 years.

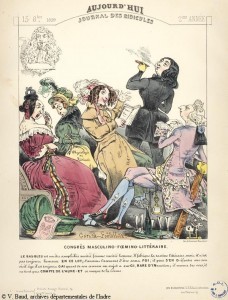

1848 caricature of George Sand as “half woman half man”

In the first instance, female revolutionaries, who had demanded freedom of dress and the right to wear pantaloons, likely prompted the need for the ordinance—which was dated as “16 brumaire of the year IX,” in the idiom of the short-lived Republican calendar (created to erase any traces of the ancien régime and abandoned upon Napoleon’s defeat). But as the century progressed, the targets of this law shifted, while the policing of gender transgressions remained real. In 1853, as writer George Sand was regularly caricatured for her manly attire, a law against cross-dressing was added to the Penal Code, forbidding cross-dressing at balls and public spaces; in the 1880s, as young women entered increasingly public roles, the police issued circulars and reminders that the law against wearing pants was in still in place; in a loosening of the law in 1909, women “holding by hand bicycles or the reins of a horse” were granted special permission to go out in public “en culotte.”

It’s unclear exactly how many women secured the permit over the course of the century. As historian Christine Bard has documented, the archives of the Parisian prefecture are frustratingly idiosyncratic, making it difficult to come to any general conclusions. But the documents therein are hardly uninteresting.

The health requirement seems to have been loosely defined at best. The first permit—from 1806—allowed Catherine-Marguerite Mayer to wear pants in order to ride her horse. A certain Mademoiselle Foucaud acquired the permit a few decades later in order to get a printing job reserved for men, which she had discovered paid better. A clipping from a 1911 newspaper preserved in the archive suggests that she was not alone: several women had permits allowing them to pass as men professionally. Indeed, in addition to the increased comfort and agility that pants allowed (the alternative, especially in the second half of the century, being the waist-squeezing corset), wearing men’s clothing paid dividends: not only could women hold men’s jobs, but they saved money on clothing that was less expensive and lasted longer. While financial necessity seemed to inspire some requests, others were granted to women whose appearance had a naturally “masculine look.” Allowing them to wear pants was seen as protecting them from the prying eyes of an unsympathetic public.

Rosa Bonheur in her garden

Hardly a trace can be found in these archives of the most famous female pants-wearers of nineteenth-century Paris—those who wore pants without permits (George Sand)—nor those we know to have procured them: the writer Rachilde, the explorer Jane Dieulafoy, or the painter Rosa Bonheur. Fortunately, they left behind other clues to their sartorial challenges.

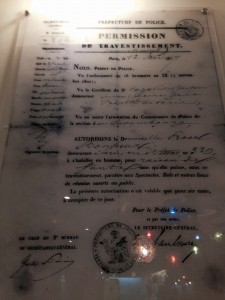

Rosa Bonheur’s “permission de travestissement,” under glass at the Café Rosa Bonheur in Paris

The café named for Bonheur in Paris’s nineteenth arrondissement—a trending Parisian hot spot tucked in the Buttes de Chaumont park where a campy chorus sings each Sunday evening—displays her permit on the wall. Citing the original ordinance, it authorizes Bonheur to “dress as a man” as of May 12, 1857, to be renewed every six months. The form lists “health reasons” in the appropriate slot (interesting in itself, suggesting that there were reasons allowed beyond medical ones) and notes that this release does not apply to “shows, balls, and other meeting events open to the public.” And there were health reasons of sorts: Bonheur wore pants and heavy boots to navigate the farms where she painted the animal tableaux that gained her fame. But her pants-wearing was also linked to a progressive gender expression, matching her closely cropped hair. She lived on a farm with her lover Nathalie Micas, whose family had taken her in as a young girl. A beloved figure, in 1865 Bonheur was awarded the Legion of Honor for her acclaimed work, and is widely considered the most influential woman artist of the nineteenth century.

While we don’t have her actual permit, we do have Rachilde’s letter of application, in which she claimed that she needed to wear pants to practice as a journalist (as writing books, she lamented, don’t pay the rent). But the plea for pants is not a request to be allowed to pass as a man; rather, she wanted to be able to stand out, because “in journalism, originality is a must.” In the letter (which, incidentally, was unsuccessful, but a permit was later granted), Rachilde reminds the prefect that she is the author of the scandalous novel Monsieur Vénus. In that novel, cross-dressers abound, as protagonists Raoule de Vénérande and Jacques Silvert delight in switching gender roles in order to shock and confound friends and family. Already in the 1880s, Rachilde understood gender as performance; she also shifted her own performance of gender and stopped wearing pants after her reputation as an “original” had been secured by the 1890s and she married fellow writer Alfred Valette.

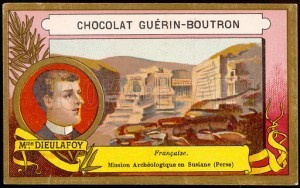

Jane Dieulafoy on the cover of a chocolate wrapper.

Finally, one of the most famous cross-dressers of the century’s close was the intrepid archaelogist-explorer-writer Jane Dieulafoy, who had begun wearing pants when she rose to battle with her husband Marcel during the Franco-Prussian war. She resumed this practice on her travels with him to Persia and later to Baghdad, and secured the required permit when they settled in Paris in the 1890s. Dieulafoy never wore women’s clothing again, and was frequently mistaken for a man. Like Bonheur, she was a beloved figure, awarded the Legion of Honor and considered a testament to the very honor of France.

Taken together, these brief portraits suggest that the ways in which women expressed their gender in nineteenth-century France—a time of rigid gender bifurcation—could be unexpectedly diverse, and that women’s motivations to dress in non-traditional ways were multiple and fluid. Women wore pants in the nineteenth century to earn better wages, to participate fully in certain activities, to hide from sight, to attract attention, to express their sexuality, to advocate for feminist rights, to rebel, to shock: in other words, to express themselves. And as the examples of Bonheur and Dieulafoy demonstrate, not all of these women were shunned—though many were.

In 2013, the law of 1800 was finally repealed. The minister for Women’s Rights, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, who headed the initiative, described the law as incompatible with French values of equality, concluding: “The document is nothing but a museum piece.” It’s worth noting, though, that if you google Vallaud-Belkacem, you will find far more about her own fashion choices than you will about this important work in closing an unfortunate chapter in the policing of French women’s clothing.

Further reading:

Bard, Christine. “Le ‘DB58’ aux Archives de la Préfecture de Police,” in Bard and Nicole Pellegrin, ed. Femmes travesties: un “mauvais” genre. Spec. issue of CLIO. Histoires, femmes et sociétés 10 (1999): 1-20.

Hawthorne, Melanie. Rachilde and French Women’s Authorship: From Decadence to Modernism. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2001.

September 1, 2015

From Scholar to Archive Thief

By Lisa Moses Leff (Guest Contributor)

I first heard of Zosa Szajkowski (1911-78) as a student of French Jewish history. Szajkowski is a founding father of the field, author of almost two hundred academic studies. And yet, if you mention his name in the archives, you will probably hear a disturbing story: while doing his research, he also raided public archives and private synagogues across France, taking thousands of the documents that interested him back to New York. There, he used the material for his articles, and eventually sold much of it to libraries in the United States for a tidy profit.

The results of the thefts and sales are staggering. Most of the vast holdings of French Jewish papers that are now held in American Jewish research libraries—tens of thousands of pages in all—seem to have been purchased from Szajkowski in the 1950s and 60s. But if these facts are well known today, the motives are less so. What led this respected historian to become an archive thief?

The results of the thefts and sales are staggering. Most of the vast holdings of French Jewish papers that are now held in American Jewish research libraries—tens of thousands of pages in all—seem to have been purchased from Szajkowski in the 1950s and 60s. But if these facts are well known today, the motives are less so. What led this respected historian to become an archive thief?

Szajkowski first felt the lure of the archives as a young Polish immigrant living in Paris in the 1930s. Among Yiddish-speaking intellectuals in interwar Europe, collecting old papers that documented the Jewish past was part of an increasingly important nationalist project. Migration and modernization were transforming Jewish life beyond recognition, and in 1925, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research was founded to preserve Jewish culture through scholarship. Szajkowski was inspired by YIVO’s project, and devoted himself to gathering material for its archives.

When World War II came, Szajkowski escaped to New York and joined the U.S. Army. As a soldier, distraught with what he saw, he grew more passionate than ever about collecting for YIVO, hoping the papers would help Jewish intellectuals make sense of what had happened and rebuild. He sought out rare documents about the persecution, sending everything he could to YIVO in New York. Even though much of his collecting was technically against Army regulations, he was treated as a hero in New York for rescuing these remnants from the wreckage of European Jewish life.

But then, after the war, this rescuer became a thief. What had started as a passion to collect became a compulsion to steal, as the psychologically unbalanced and financially strapped historian sought to make his way in America. Lacking a PhD and even a high school degree, he was never able to get an academic job, but he remained as dedicated to scholarship as ever. His buyers were eager for the rare documents he sold, seeking to help the struggling scholar and also to build their collections.

Szajkowski’s story is by turns heroic and sordid, and only makes sense when considered in light of the Holocaust and its aftermath. It reveals the powerful ideological, economic, and psychological forces that made the Jewish scholars of his era care so deeply about preserving the remnants of their past.

Lisa Moses Leff is author of The Archive Thief: the Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford, 2015). She is Associate Professor of History at American University in Washington, D.C. For more information, see http://www.american.edu/cas/faculty/leff.cfm

Lisa Moses Leff is author of The Archive Thief: the Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford, 2015). She is Associate Professor of History at American University in Washington, D.C. For more information, see http://www.american.edu/cas/faculty/leff.cfm

August 27, 2015

Fred Harvey and His Bird’s Eye View of History

By Stephen Fried (Guest Contributor)

When I set out to write a book about Fred Harvey–who all but invented the American hospitality industry at his trackside restaurants and hotels between Chicago and Los Angeles along the Santa Fe–I thought I’d be writing a business biography set in the late 1800s, with some nice historical touches of the Wild West. It didn’t occur to me until about six months into the process that the story would actually have to extend two generations beyond Fred—all the way through the 1940s (when the physicists from Los Alamos used the Fred Harvey hotel, La Fonda, as their regular Santa Fe watering hole for successes and setbacks.) So instead of a historical biography, the book would need to be, for lack of a better term, a biographical history (which is why it took six years and not the two I promised my publisher.)

When I set out to write a book about Fred Harvey–who all but invented the American hospitality industry at his trackside restaurants and hotels between Chicago and Los Angeles along the Santa Fe–I thought I’d be writing a business biography set in the late 1800s, with some nice historical touches of the Wild West. It didn’t occur to me until about six months into the process that the story would actually have to extend two generations beyond Fred—all the way through the 1940s (when the physicists from Los Alamos used the Fred Harvey hotel, La Fonda, as their regular Santa Fe watering hole for successes and setbacks.) So instead of a historical biography, the book would need to be, for lack of a better term, a biographical history (which is why it took six years and not the two I promised my publisher.)

Fred, his son Ford, their top managers and the generations of their beloved waitresses, the “Harvey Girls” were afforded a birds-eye view of an enormous number of events in U.S. history that we often take for granted, and sometimes learn about pretty dryly. So I decided to recreate as many of the events that Fred and his employees experienced as I could, based on a new reading of original newspaper accounts (some on microfilm others, mercifully, now available on ProQuest) and then cross-referenced with the cache of never-before-seen Harvey family datebooks, correspondence and business files, as well as Santa Fe railroad archives.

From the manhunt for the escaped “Billy the Kid” in 1881 (a local celebrity in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where Fred had two restaurants and two hotels, which Billy sometimes patronized), to the Oklahoma Land Rush in 1889 (which left from the Arkansas City, Kansas Harvey House and Santa Fe depot), to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 (for which Fred helped cater the biggest lunch in American history for the opening ceremonies and parade).

There’s also the Rough Riders reunion in 1899 (held at the new Fred Harvey resort hotel, La Castañeda, in Las Vegas), and the development of the Grand Canyon as an international tourist attraction (Fred’s son Ford ran all the hotels at the canyon, and was a major player in the development of the national park system).

And, we can’t forget Teddy Roosevelt’s famed environmental address at the Canyon edge (which turns out to have been prompted, in part over a fight concerning the placement of the Harvey hotel there), or the first transcontinental air flights in 1929 (Fred’s grandson Freddy, a WWI pilot, was an original partner with Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, Glenn Curtiss and others in the company that became TWA; the first transcontinental air passenger meals were Harvey meals), or the Kansas City Massacre in 1933 (which took place in the Union Station where the Harvey company was headquartered, with bullets flying over the heads of Harvey Girls), … well, the list really does go on.

Probably my favorite historical recreation was Albert Einstein’s 1930 visit to America, which was highlighted by the day he came to the Grand Canyon, and was greeted by Hopi Indians he thought just liked him—and didn’t realize they worked for Fred Harvey. They wanted to make him an honorary chief—as they did for all visiting dignitaries—but they didn’t know who he was.

“What’s his business?” they asked their boss, Herman Schweizer, who ran the famed Harvey Indian art business.

“He invented the Theory of Relativity,” he replied.

“All right,” they said, “we’ll call him ‘Great Relative.’”

Stephen Fried is an award-winning investigative journalist and essayist, and an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s graduate school of journalism. He is the author of the highly praised books Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia, Bitter Pills: Inside the Hazardous World of Legal Drugs, The New Rabbi, and Husbandry: Sex, Love & Dirty Laundry—Inside the Minds of Married Men. A two-time winner of the National Magazine Award–the Pulitzer Prize of magazine writing–Fried has been a prolific writer of feature stories and personal essays for various other publications. His new book, Appetite for America: How Visionary Business Man Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West

Stephen Fried is an award-winning investigative journalist and essayist, and an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s graduate school of journalism. He is the author of the highly praised books Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia, Bitter Pills: Inside the Hazardous World of Legal Drugs, The New Rabbi, and Husbandry: Sex, Love & Dirty Laundry—Inside the Minds of Married Men. A two-time winner of the National Magazine Award–the Pulitzer Prize of magazine writing–Fried has been a prolific writer of feature stories and personal essays for various other publications. His new book, Appetite for America: How Visionary Business Man Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West , is available now (Bantam). To read more about the book and the author, please click here.

, is available now (Bantam). To read more about the book and the author, please click here.

IMAGE: Albert Einstein at the Grand Canyon with Fred Harvey employees, courtesy of El Tovar Studio, Fred Harvey Collection, Grand Canyon National Park

August 25, 2015

Beyond Blazing Saddles: The African-American West

By Michael K. Johnson (Guest Contributor)

A former slave, Irvin Smith, travelled up the Missouri River and eventually landed in 1880 in White Sulphur Springs, Montana Territory, where he owned and operated a blacksmith shop for twenty years.

Millie Ringold came to frontier Montana after the Civil War as a servant, but soon set off on her own to the town of Yogo, where she discovered a sapphire in a goose that she was preparing for dinner. She quickly staked a claim and became something of a rarity in the American West: an African American woman prospector.

Oscar Micheaux

Nat Love wrote an autobiography about his life and adventures as a cowboy. Era Bell Thompson wrote about her experiences as a member of one of the few African American families homesteading in North Dakota, and Oscar Micheaux wrote about his homesteading experience in South Dakota.

When I tell people that my primary research interest is the African American West, the response is usually surprise. Even though African Americans currently live in all areas of the American West, and even though people of African descent have participated in every frontier expansion (from a 1528 Spanish expedition that included the slave Esteban to the Oklahoma land rush), we seem to have trouble including black people in the histories of and the stories we tell about the American West.

When I tell people that I’m particularly interested in the African American West in literature, film, and television, they’re really surprised. “You mean, like Blazing Saddles?”

Well, yes, and more recently, Django Unchained, but, as I explore in my book Hoo-Doo Cowboys and Bronze Buckaroos, those two relatively recent films are just a small sample of a wide range of African American westerns and other stories of black life in the West. The birth of African American independent filmmaking took place in the West and emphasized western stories: Noble Johnson’s The Realization of of a Negro’s Ambitions (1916) and Oscar Micheaux’s (based on his memoir) The Homesteader (1919). Throughout the “race film” era (films made specifically for black audiences in segregated theaters), filmmakers often returned to the American West as a setting—culminating in a series of all-black-cast sound westerns featuring Herb Jeffries as singing cowboy Bob Blake (and including films such as The Two-Gun Man from Harlem and The Bronze Buckaroo).

Well, yes, and more recently, Django Unchained, but, as I explore in my book Hoo-Doo Cowboys and Bronze Buckaroos, those two relatively recent films are just a small sample of a wide range of African American westerns and other stories of black life in the West. The birth of African American independent filmmaking took place in the West and emphasized western stories: Noble Johnson’s The Realization of of a Negro’s Ambitions (1916) and Oscar Micheaux’s (based on his memoir) The Homesteader (1919). Throughout the “race film” era (films made specifically for black audiences in segregated theaters), filmmakers often returned to the American West as a setting—culminating in a series of all-black-cast sound westerns featuring Herb Jeffries as singing cowboy Bob Blake (and including films such as The Two-Gun Man from Harlem and The Bronze Buckaroo).

African American characters were frequently featured in the first sound-era westerns of the 1930s, and as westerns came to dominate the television landscape of the 1960s and early 1970s, series westerns such as The Rifleman, Rawhide, Bonanza, and Gunsmoke offered episodes that focused on African American characters (played by stars such as Sammy Davis Jr., Woody Strode, and Louis Gossett Jr.).

And there’s a literary tradition of African American writers telling western and frontier stories that stretches from John Marrant’s 1785 captivity narrative to Percival Everett’s novel Wounded (2005).

Hoo-Doo Cowboys and Bronze Buckaroos takes a journey of discovery into the African American West, exploring the fascinating range of ways black western experience has been imagined, represented, and performed.

Michael K. Johnson is Professor of American literature at the University of Maine at Farmington. He is the author of Black Masculinity and the Frontier Myth in American Literature (University of Oklahoma Press) and Hoo-Doo Cowboys and Bronze Buckaroos: Conceptions of the African American West (University Press of Mississippi).

August 24, 2015

Closing the Border

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Concerns that immigrants flooding across the border threaten the nation’s basic institutions. Construction of armed posts to defend the border. Passage of new, more restrictive immigration laws. Sound familiar? Welcome to Mexico in 1830.

The story began when Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821. At first the newly independent country welcomed settlers from the United States. The government signed contracts with immigration brokers, called empresarios, who agreed to settle a set number of immigrants on a set piece of property in a set amount of time. In exchange for the right to buy land, settlers agreed to obey Mexican law, become Mexican citizens, and convert to Catholicism. At the same time, the US Congress passed a new land act that made emigration to Mexico even more appealing. Public land in the US cost $1.25/acre*, for a minimum of eighty acres and could no longer be bought on credit. Public land in Mexico cost 12 1/2¢/acre and credit terms were generous. Not a hard choice for anyone who was cash-poor and land hungry.

Some empresarios brought in groups of settlers from France or Germany. More, including Stephen Austin,** brought in settlers from the southern United States. Most new colonists settled in new communities east of modern San Antonia. By the mid-1830s, Anglo settlers outnumbered native Tejanos by as many as 10 to 1 in some parts of Texas. These settlers brought the culture of the American South with them, including slaves and slavery.*** In addition, many Anglo settlers traded (illegally) with Louisiana rather than with Mexico.

Concerned about growing American economic and cultural influence in the region, the Mexican government passed a law banning immigration into Texas from the United States on April 6, 1830. They also assessed heavy customs duties on all US goods, prohibited the importation of slaves, built new forts in the border region and opened customs houses to patrol the border for illegal trade.

The law didn’t have the intended affect. Instead of re-gaining control over Texas, Anglo colonists and the Mexican government were in constant conflict. The law was repealed in 1833, too late to staunch the wound. The first shots in what would become the Texas War of Independence were fired on October 2, 1835.

*$31.44 in today’s currency. Still a bargain.

** Hence Austin, Texas. (I don’t know about you, but I’m always curious as to how a town got its name.)

***Outlawed in Mexico is 1829–so much for obeying the laws.

August 20, 2015

Bonanza Denied by Pickax and Jackass

By Caroline Lawrence (Former W&M Contributor)

In 1849 two good-looking, well-educated brothers from Pennsylvania joined the surge of young men travelling westward to “make their pile” in California gold.

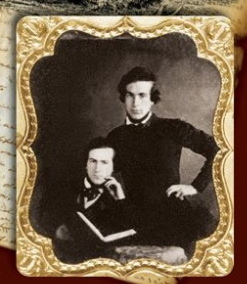

ambrotype of Allen and Hosea Grosh

Allen and Hosea Grosh endured hunger, cold, toothache, scurvy, rheumatism and so much dysentery that they had to learn to spell the word diarrhea for their letters home. After a few unproductive years in California, the Grosh brothers crossed the mountains to seek better luck in the territory that would one day be called Nevada.

Allen and Hosea weren’t mere placer miners – scraping at the surface or dabbling in streams – they were chemists and inventors. In between working on a perpetual motion machine they worked out the best ways of extracting silver from the stubborn quartz, for they were among the first to realise Nevada might be richer in silver than in gold. One of their letters home to their father mentions a “monster ledge”. Were they about to discover the massive silver deposit that would later be known as the Comstock Lode and would make Bonanza! a household word?

We will never know, for a few days later the younger brother Hosea put a pickaxe into his foot on the “inner side just under the instep”. At first it seemed like a minor wound but then the wound began to fester and the foot to swell. A poultice of bread and soda was not working fast enough, so Hosea asked for a different poultice of Indian meal. That didn’t work, so a local man recommended a poultice of “fresh cow dung.”

Grosh marker in Nevada with replica pickax

Then occurred the mishap that “sent Hosea out of this world”. While Allen was waiting for a man to bring medical supplies, “the cat jumped on the bed, and in doing so lit with all his weight on poor Hosea’s sore foot. It caused him intense pain.” The next day he died. His devoted older brother stayed long enough to bury him and settle their debts, then he set out for California.

But Allen’s diligence delayed his departure and it was now November. He was travelling with a young Canadian named Bucke, and they might have made it over the Sierra Nevada if not for a troublesome jackass that kept straying from camp at night. The time wasted looking for their pack animal caused the two men to get caught in blizzards on the same mountains that had trapped the Donner Party ten years before. Their matches got wet and their food supply was soon exhausted. Eventually they killed and ate the problematic donkey. Confused by snow, they went up the wrong peak and had to retrace their steps.

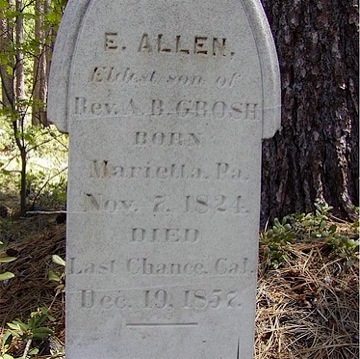

Allen’s tombstone in Last Chance

Once again without food or fire, they buried themselves in snow at night to keep warm. With their feet now badly frostbitten they finally managed to make it to a mining camp called Last Chance, literally crawling the last half-mile or so. Bucke let the doctor amputate his feet and he survived, but poor Allen died on 19 December 1857, three months after his younger brother. A poignant letter to their father records that “Mr. Grosh was buried very gently today at ½ past four o’clock.”

The editors of the letters think the Grosh brothers were based too far down the mountain to have discovered the actual Comstock Lode, but if they had lived a few years longer their expertise in chemistry and mining would surely have brought them the wealth and success they longed for.

But their dreams ended in tragedy, all because of the slip of a pickax and the wanderings of a jackass.

The Gold Rush Letters of E. Allen Grosh and Hosea B. Grosh edited by Ronald M James and Robert E Stewart are available in hardback and Kindle formats.

My own historical fiction book for kids also mentions the Grosh Brothers and gives more background to some of the colorful characters who lived on the Comstock in the early 1860s, including Mark Twain. The Case of the Deadly Desperados is out now.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in October 2012.