Holly Tucker's Blog, page 26

August 5, 2015

High on Fragrance: The Nineteenth-Century Perfume Launcher

By Cheryl Krueger (Guest Contributor)

By Cheryl Krueger (Guest Contributor)

Multi-million dollar advertising campaigns attest to a thriving perfume industry in North America and the European Union. An average of three new perfumes per day were released in 2011 alone. But not everyone is high on perfume. The International Fragrance Association (IFRA) adheres to a self-regulatory Code of Practice (perfume enthusiasts liken it to Hollywood’s Hays Code, and regularly introduces restrictions to protect consumers and the environment from potential perfume-induced dangers. France’s fragrance industry battles constant proposals from the European Commission to restrict or ban materials like natural oak moss and coumarin, longtime cornerstones of classic French perfumery. In North America especially, there is a growing movement toward fragrance-free zones, and legislation protecting office workers from the imposing, even toxic sillage of their colleagues.

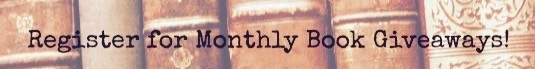

An 1896 Alfred Mucha poster advertising the Rodo perfume launcher.

This love-hate relationship with perfume is not a new phenomenon. As the modern French perfume industry boomed in the nineteenth-century, perfumers found themselves defending the safety of natural and synthetic materials in fragrant cosmetics. These included face powders, lotions, bath milks, pastes, pomades, and liquid perfumes. Concerns about the danger and abuse of perfume were expressed not by regulatory committees, but in manuals of beauty, etiquette and hygiene, the popular press, and medical treatises dealing with nervous disorders and hysteria.

Though warnings of perfume’s moral and biological toxicity were often overstated, there was one product that may have lived up to the hype: the Lance-parfum Rodo.

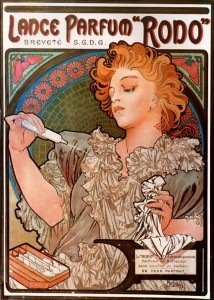

Other print ads for perfume in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries emphasized handkerchiefs, one of the many accessories that served as vehicles for personal perfuming.

Other print ads for perfume in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries emphasized handkerchiefs, one of the many accessories that served as vehicles for personal perfuming.

In fact, perfumers’ manuals show that liquid perfume (parfum liquide) was synonymous with handkerchief perfume (parfum pour le mouchoir).

So what was unique about the lance-parfum Rodo?

It happens that the device was as much a pharmaceutical product as a fragrant accessory.

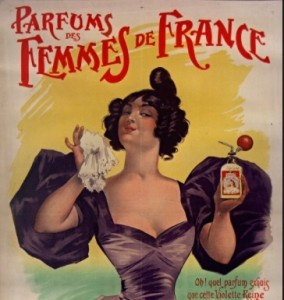

How to use the Kélène to insure speedy delivery.

Patented in 1897 by chemical manufacturer la Société Chimique des Usines du Rhône, the lance-parfum Rodo was the serendipitous reincarnation of an ethyl chloride dispenser called the Kélène lance chlorure d’ethyle, which preserved ethyl chloride in portable, single-use glass or metal tubes for use as local and general anesthesia.

The Société Chimique des Usines du Rhône manufactured both pharmaceuticals and synthetic perfume ingredients. One day violet fragrance spilled into ethyl chloride, and an idea was born. Like its medical prototype, the lance-parfum was a portable projection system for (now perfumed) ethyl chloride, released automatically when the seal was broken. When liquid ethyl chloride meets warm air, it vaporizes. This is good news for linens and white handkerchiefs.

The Lance-parfum Rodo was manufactured in a variety of scents, including heliotrope, hyacinth, lily-of-the-valley, and Peau d’Espagne. Still, the gadget is absent from popular manuals by perfumers such as Septimus Piesse, whose works were reissued in French and English throughout the nineteenth century. A column in the August 1911 issue of the trade manual La Parfumerie moderne summarizes the chemistry and mechanics of generic “lances-parfums,” emphasizing the refreshing sensation produced by solvents including ethyl chloride, but also deeming the gadgets dangerous because they are highly flammable (“Recettes et Procédés Utiles”107-108).

A Rodo perfume launcher from the author’s collection.

The lance-parfum was heavily marketed at the Rio Carnival, where users reportedly suffered intoxication, hallucinations, and cardiac trouble. Due to deaths related to lance-parfum abuse, the product was finally outlawed in the 1960s.

Was lance-parfum swooning similarly rampant in fin-de-siecle France? If so, not for long. Though other French companies applied for patents, the threat of the Great War brought most marketing plans to an early halt. (1) It is possible, though, that the presence of ethyl chloride-based perfumes helped to fuel less convincingly substantiated reports of eccentric fin-de-siècle perfuming, such as subcutaneous perfume injection, perfume drinking, and the unusual case of a scent-huffer getting high on Guerlain’s groundbreaking 1889 Jicky perfume. (2)

[1] For a detailed review of the development and patent history of the lance-parfum, see Raynal, Cécile and Thierry Lefebvre, “Le Lance-parfum. Un matériel médical devenu accessoire de carnaval.” Revue d’histoire de la pharmacie 56.357 (2008): 63-79.

[2] Reported in Antoine Combe’s Influence des parfums et des odeurs sur les névropathes et les hystériques (Paris: A. Michalon): 1905.

Cheryl Krueger is Associate Professor of French at the University of Virginia. You can read more about alleged fin-de-siècle perfume abuse in her article Decadent Perfume: Under the Skin and Through the Page.

Any questions about Bric-a-brac-o-mania, W&M’s new column about nineteenth-century cultural artifacts and more? Contact Rachel Mesch, rachel.mesch@gmail.com.

August 4, 2015

Rascals & Rogues & Oily Hucksters

By Matthew P. Mayo (Guest Contributor)

For as long as I can recall I’ve been inordinately intrigued by the nefarious deeds of ne’er-do-wells. As a lad I reveled in reading books about sleazy people and the vicious circumstances their willful actions instigated. Years later I find myself writing books about dire situations, daring exploits, and oily hucksters of the lowest order. And I’m having the time of my life.

My latest book (out today, in fact) is Hornswogglers, Fourflushers & Snake-Oil Salesmen: True Tales of the Old West’s Sleaziest Swindlers. I spent more than a year in the company of the weasels who populate its pages, researching their misdeeds and finding myself more amazed with each stack of notes I jotted.

As I pieced together their stories, I wondered once more why I am so amazed by the exploits of these rogues. Is it their brazen attitudes? The confidence they exude? Their lack of remorse? Likely, it’s a combination of those traits and many others.

It’s too easy to say that the moral compasses of these men and women were warped by an off-kilter magnetic force that drove them to depraved depths. The real reasons are legion and more complex than simple explanation will allow. That said, they all shared certain traits.

Chicago millionaires Albert and Bessie Johnson with “Death Valley Scotty.”

These bad seeds dared to risk so much of their lives—more than most law-abiding folks could ever dream of risking—to achieve their ends, ends that most often involved amassing power and money, one often leading to the other. But the thing that made me want to write about them is the very thing that marks them as swindlers—their intentional duping of others.

Take Death Valley Scotty, for instance. He was as charismatic and likable a rogue as you were likely to meet. He was also famous for being a trick rider in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show long before he hit on the idea of bilking millionaires out of copious sums of cash as seed money in gold mines that never existed. And his biggest investor continued subsidizing Scotty’s lavish life even after he found out he was being conned.

Death Valley Ranch

Incredibly, the man he bilked more than any other, Chicago millionaire Albert Johnson, and his wife, Bessie, were so taken by the con man, and by Death Valley itself, that they built Death Valley Ranch (left), more commonly known as Scotty’s Castle. They even allowed Scotty to tell visitors they were his hired help.

And then there was Soapy Smith, who bilked and cheated his way for years from the southwest through Colorado and on up to Alaska. There his thieving misdeeds eventually instigated gunplay that resulted in his death, albeit years too late to save thousands of suckers from his swindling schemes.

“Clark’s Snake Oil Liniment” sold like gangbusters.

And let us not overlook Clark Stanley, the self-proclaimed “Rattle-Snake King,” and the man for whom the term “snake-oil salesman” was coined. His greasy dealings resulted in a fortune for himself and bottles filled with useless mineral oil for his victims, er, customers.

While writing the book, I realized that every one of the dozens of rascals I profile (a mere sliver of those plying the flimflam trade in the US West of the 19th and early 20th centuries) would not find themselves out of place or, more to the point, out of work, were they operating today. Indeed, we all wade in morally murkier waters today than ever before.

My windy point? Nothing changes. I doubt there’s a cure. It’s the never-ending cycle of predator versus prey. The best we can do is keep a sharp eye on our backtrail, and trust that the good, hardworking folks outnumber the sleazeballs among us.

Speaking of … I have this book, see, and it’s a corker! A real humdinger! So step right up, folks—for a few meager bucks, get yourself a copy of Hornswogglers, Fourflushers & Snake-Oil Salesmen: True Tales of the Old West’s Sleaziest Swindlers before they’re all gone!

But wait! For a few dollars more you’ll be sent a deed, suitable for framing, to shares in a diamond mine. It should prove out any day now….

Matthew P. Mayo is an award-winning author of thirty non-fiction books and novels, and dozens of short stories. His 2013 novel, Tucker’s Reckoning, won the Western Writers of America’s Spur Award for Best Western Novel. Matthew and his wife, photographer Jennifer Smith-Mayo, also run Gritty Press (GrittyPress.com) and rove the world in search of hot coffee, tasty whiskey, and high adventure. Stop by his website for a chinwag.

Matthew P. Mayo is an award-winning author of thirty non-fiction books and novels, and dozens of short stories. His 2013 novel, Tucker’s Reckoning, won the Western Writers of America’s Spur Award for Best Western Novel. Matthew and his wife, photographer Jennifer Smith-Mayo, also run Gritty Press (GrittyPress.com) and rove the world in search of hot coffee, tasty whiskey, and high adventure. Stop by his website for a chinwag.

W&M is excited to have five (5) copies of Hornswogglers, Fourflushers, and Snake-Oil Salesmen in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on August 27th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

August Book Giveaways

Schechner, Ulrich, Gaskell, Carter, van Gerbig, “Tangible Things: Making History through Objects”

Matthew P. Mayo, “Hornswogglers, Fourflushers & Snake-Oil Salesmen”

Robert Barr Smith, “Outlaw Women: America’s Most Notorious Daughters, Wives, and Mothers”

August 3, 2015

Dinosaurs with Native American Names

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

The most well known scientific name for a dinosaur derived from Native American culture is Brontosaurus, a tremendous 60-foot long sauropod described by Othniel Marsh in 1879. The name means “Thunder Lizard,” in honor of the Sioux fossil scouts who showed Marsh the colossal skeletons of extinct creatures they called “Thunder Beasts.”

The most well known scientific name for a dinosaur derived from Native American culture is Brontosaurus, a tremendous 60-foot long sauropod described by Othniel Marsh in 1879. The name means “Thunder Lizard,” in honor of the Sioux fossil scouts who showed Marsh the colossal skeletons of extinct creatures they called “Thunder Beasts.”

Native Americans led many paleontologists to world-famous deposits of dinosaur and other prehistorical animals in the American West, beginning in the 19th century. The guides explained their tribes’ mythology and knowledge of the strange, gigantic beings that once flourished and then vanished, leaving their stony remains in the ground.

This historical cultural exchange resulted in numerous American Indian myths, names, legends, and lore about dinosaurs and other extinct species commemorated in scientific nomenclature for fossils. Sioux languages are well represented. Examples include Iguanodon lakotaensis (a Cretaceous dinosaur); the large rodents Manitsha tanka, Campestrallomys siouxensis, and Hitonkala; the hippo-like anthracothere Kukusepasutanka, and the fossil mammal Ekgmoiteplecela. Paleontologist J. Reid MacDonald bestowed Lakota Sioux designations on several Oligocene mammals of the White River Badlands, such as Sunkahetanka, “dog with large teeth.” The name Ekgmowechashala for the primate fossil discovered near Wounded Knee, Pine Ridge Reservation, is Sioux for “monkey” or “little cat man.” A new species of Jurassic apatosaur was discovered in 1994 in Wyoming, the first sauropod dinosaur with a complete set of “belly ribs.” The paleontologists named the dinosaur Yahnahpin because they noticed that the ribs bear a striking resemblance to Lakota Sioux warriors’ chest armor, mah-koo yah-nah-pin (“chest necklace”).

In 1873, Joseph Leidy named a fossil carnivore Sinopa, the Blackfeet word for “small fox.” In 1989 in northern Montana, R. Lund named a new petalodontiform chondrichthyian fossil Siksika (“black foot”) for the Blackfeet nation.

Quetzalcoatlus, the giant pterosaur, was named after the Aztec Feathered Serpent god. The pterosaurs Tupuxuara and Tapejara are names of spirits in Tupi mythology of Brazil. The theropod dinosaur Ilokelesia of Patagonia comes from Mapuche words ilo (flesh) and kelesio (lizard), and the tyranosauroid Megaraptor namunhuaiquii is Mapuche for “foot lance.”

Douglas Wolfe dubbed the new horned dinosaur Zuniceratops to honor the Zuni on whose land the fossils were discovered. A Cretaceous marsupial of the Southwest is named Kokopelia after the familiar flute-playing figure Kokopeli in Navajo rock art. Two hadrosaur dinosaurs of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, Naashoibitosaurus and Anasazisaurus, are part of the taxonomic nomenclature associated with Kritosaurus navajovius, named by Barnum Brown in 1910.

The enormous marine reptiles Tylosaurus nepaeolicus and Liodon nepaeolicus, described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1874, were found in the gray shale of the Solomon River in Kansas. The species name comes from “Nepaholla,” the Pawnee name for the Solomon River.

NOTE. Thanks to all my paleontologist friends who supplied examples of Indian languages preserved in fossil species’ scientific names. For the history of Native American discoveries and interpretations of dinosaur and other fossils, see my book “Fossil Legends of the First Americans” (2005).

August 1, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Pop Culture’s Past

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Summer is beginning to wind down for many, but we are trying to hold onto some summer fun here at Wonders & Marvels. So this week we are focusing on a little more frivolous but very fun stories of yesteryear!

Let’s consider the tattoo: the ultimate symbol of rebellion from societal norms. Getting “inked” may be more common than ever, but we still hear the voices of past generations saying “back in my day…”. Well it turns out, that back in their day the tattoo was already making its mark (pun intended). A new book, 100 Years of Tattoos reveals vintage images of head-to-toe tattoos from as early as the 1920’s. So next time grandma complains about your ink, share some of these throwback photos to make your case!

Many of these tattooed ladies toured the carnival circuit where you would also find lots of daredevils risking their necks in various pursuits, like the classic roller coaster. It turns out that the roller coaster started with Russian daredevils who created flying mountains for sledding in the 1600’s. The French adapted this to include a track and wheels in 1804, much more closely resembling the modern coasters. To learn more about the history of this vintage ride, check out From Russia with Love: The History of the Roller Coaster.

Many of these tattooed ladies toured the carnival circuit where you would also find lots of daredevils risking their necks in various pursuits, like the classic roller coaster. It turns out that the roller coaster started with Russian daredevils who created flying mountains for sledding in the 1600’s. The French adapted this to include a track and wheels in 1804, much more closely resembling the modern coasters. To learn more about the history of this vintage ride, check out From Russia with Love: The History of the Roller Coaster.

As American as Apple Pie

Roller coasters are synonymous with summer fun, but perhaps your idea of fun is more along the lines of picnicking by a gurgling stream. If so, you will enjoy the depiction of a 19th century American boyhood found in the Nelson archive at Amherst College. This rare collection features photographs along with writing a nd drawings by the Nelson children from a typical American farm family. This rare glimpse at rural childhood will have you longing for apple pie in the sunshine.

nd drawings by the Nelson children from a typical American farm family. This rare glimpse at rural childhood will have you longing for apple pie in the sunshine.

Fast forward a few years and imagine 1950’s suburban America. Your vision of the housewife, neat home, and manicured lawn may also feature one more icon: the pink flamingo. Invented in 1957 the plastic pink flamingo perched on two metal legs has become the ultimate symbol of “kitsch”. However, a recent Time article reveals how much more this flamboyant feathered friend says about popular culture and class in America.

For more fun reads, take a look at these recent articles on Wonders & Marvels:

Talking to the Beyond through the Luminiferous Ether

Lincoln’s Funeral was a Letdown

The Duchess Mazarin, Runaway Woman and Traveling Corpse

July 31, 2015

Tortoises Sail the Sea

By Sara J. Schechner (Guest Contributor)

The dome-shaped shell was once a walking signboard. Graffiti cut by sailors into the shell reads “SHIP ABIGAIL / 1835 B[en]j[amin] Clark / MASTER.” Now the Galapagos tortoise specimen R-11064 belongs to Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

She came from an archipelago of volcanic islands that Herman Melville considered spellbound and cursed. “Take five-and-twenty heaps of cinders dumped here and there in an outside city lot; imagine some of them magnified into mountains and the vacant lot the sea; and you will have a fit idea of the general aspect of the Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles,” Melville wrote in 1854. “Little but reptile life is here found….No voice, no low, no howl is heard; the chief sound of life here is a hiss.”

Whaling crews, however, found the Galapagos a welcome source of refreshment. The Abigail of New Bedford, a ship under the command of Captain Benjamin Clark, reached the islands in May 1834 and took onboard 140 tortoises. Able to survive without food or water for as long as a year, the creatures provided fresh meat to the crew for many months. They were piled among the barrels of sperm whale oil in the hold or allowed to roam the decks as pets. This specimen was likely eaten near the end of the voyage and so made it back to Massachusetts as a souvenir in June 1835.

Charles Darwin ate his share of tortoise meat when the Beagle visited the Galapagos that same year. Nine months later he began to consider the distribution of tortoises of diverse sizes and shapes among the islands as possible evidence for the instability of species and the influence of environment on their diversification.

Starting in 1824, the tortoises throughout the archipelago were described by zoologists as a single species, Testudo nigra, and the ship Abigail specimen was identified as the holotype—i.e., the specimen used by scientists to define this species. More recently, DNA analysis has concluded that there are fifteen known species (Geochelone spp.), three of which are extinct.

Old museum records indicated that the Abigail specimen had been collected on Charles Island, although it was not the native type found there. Scientists speculated that it had floated to Charles after being cast overboard by buccaneers clearing their decks before a battle. The scientific riddle was solved by historical research. According to the Abigail’s logbook preserved in the New Bedford Free Public Library, the tortoise was actually caught on Porter’s Island where it was the native type.

In the early 1840s, Melville was fascinated by the tortoises that nightly trudged along the deck of his whaling ship in the Pacific. His recollections were so vivid that he fancied he spied them in the corner shadows of candle-lit old mansions in Massachusetts, “slowly emerging from those imagined solitudes, and heavily crawling along the floor, the ghost of a gigantic tortoise, with ‘Memento * * * * *’ burning in live letters upon his back.”

So how do we classify this tortoise marked “SHIP ABIGAIL ”? As the most fundamental of scientific specimens, dinner scraps from the world of whaling ships, a message written large on an Ecuadorian reptile, or an enchanted muse for our time?

Sara J. Schechner is the David P. Wheatland Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at Harvard University, where is she is part of the history of science department and has taught museum studies. She recently received the Joseph H. Hazen Education Prize (2008) of the History of Science Society for a career of innovative and diverse object-based teaching. She lives in a historic house on the National Register and has an archaeological site in her back yard. She is one of the authors of Tangible Things: Making History through Objects, along with Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Ivan Gaskell, Sarah Anne Carter, and Samantha van Gerbig.

Sara J. Schechner is the David P. Wheatland Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at Harvard University, where is she is part of the history of science department and has taught museum studies. She recently received the Joseph H. Hazen Education Prize (2008) of the History of Science Society for a career of innovative and diverse object-based teaching. She lives in a historic house on the National Register and has an archaeological site in her back yard. She is one of the authors of Tangible Things: Making History through Objects, along with Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Ivan Gaskell, Sarah Anne Carter, and Samantha van Gerbig.

July 30, 2015

The Busy Posthumous Life of Genevieve

By David Powell (Guest Contributor)

In November 1793, the oldest victim of the Reign of Terror went quietly to her fate. She had already been dead for nearly thirteen centuries, but that did not mollify the revolutionaries who had exhumed Saint Genevieve of Nanterre from the crypt beneath the Parisian abbey that bore her name.

In November 1793, the oldest victim of the Reign of Terror went quietly to her fate. She had already been dead for nearly thirteen centuries, but that did not mollify the revolutionaries who had exhumed Saint Genevieve of Nanterre from the crypt beneath the Parisian abbey that bore her name.

Her ornate, early medieval reliquary, gilded in gold and silver and encrusted with diamonds and other gems, was taken to the city mint over the protest of hundreds of the saint’s admirers. There, behind locked doors, assayers valued the ancient coffin at 23,800 livres. They then dismantled it.

Within, wrapped in white linen, they found “the bones of a cadaver and a head on which there were many deposits of gypsum or plaster.”

They also found a tiny piece of ancient parchment with an inscription: Hic jacet humatum corpus sanctae Genovefae. “Here lies buried the body of holy Genevieve.”

It was an undignified end for the patron saint of Paris. Genevieve was a shepherdess from nearby Nanterre who, as the governing apparatus of the Roman Empire receded from 5th century Gaul, gained widespread fame for her piety and charity. When Attila the Hun, the “Scourge of God,” threatened Paris in 451, a prayer vigil led by Genevieve was credited with saving the city from his wrath.

After her death, she was interred atop the hill that would later be home to the city’s Latin Quarter. Her shrine, just east of the town’s disused Roman forum, quickly became a pilgrimage site. Even in death, she remained active. In the centuries to come, as Paris bloomed around her, every grave threat to the city was met by a procession featuring her sarcophagus: war, plague, famine…even high water. The Marquise de Sevigny described a 1675 procession meant to end a series of flooding rainstorms:

“Monks of every order walk in it, and all the parish clergy and the canons of Notre-Dame, his Grace the Archbishop, in pontifical robes, on foot, and blessing the people right and left all the way to the cathedral. However he walks only on the left side. On the right walks the Abbot of Sainte-Genevieve, barefooted, preceded by 150 monks, also barefooted …The Parliament in red robes and all the higher guilds follow the shrine, which sparkles with precious stones, and is carried by twenty-two barefooted men clad in white. The head of the merchant guilds and five councillors are left as hostages at the Abbey of Sainte-Genevieve until the return of [the saint’s relics].”

By 1793, her fame had become a liability. Her bones were tried for treasonous collaboration with the Bourbon royal family, found guilty, and burned at the Place de Grève (now the Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville). The few remaining fragments of her body were later reburied at the Church of St. Stephen, where they remain today. Nearby, the city’s Pantheon stands on the former site of her shrine and is the final resting place of Voltaire and other secular titans of France. The building’s intended purpose remains visible, however, in the murals that decorate its vaulted interior, which depict the life of a shepherd girl from Nanterre.

David P. Powell studies ancient and medieval Europe in the graduate history program at Villanova University. When the urge seizes him, he writes about the topic at his blog, Studenda Mira.

Further reading:

Bitel, Lisa. Landscape with Two Saints: How Genovefa of Paris and Brigit of Kildare Built Christianity in Barbarian Europe. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Sluhovsky, Moshe. Patroness of Paris: Rituals of Devotion in Early Modern France. Brill, 1998.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in March 2010.

July 28, 2015

Lincoln’s Funeral was a Letdown

By Martha Hodes (Guest Contributor)

Awe-inspiring, somber, sorrowful: That’s how mourners imagined the forthcoming funeral of President Abraham Lincoln, in the terrible hours and days after the nation’s first presidential assassination. The Union had just won the Civil War when the aggrieved actor, John Wilkes Booth, fired his pistol at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865.

T he funeral would begin on April 18, with three days of rituals in the capital. Lincoln’s body would then travel north and west on an extravagant funeral train, to be removed for elaborate services in ten cities along the way. After two weeks and nearly 1700 miles, the slain president would be laid to rest in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois.

he funeral would begin on April 18, with three days of rituals in the capital. Lincoln’s body would then travel north and west on an extravagant funeral train, to be removed for elaborate services in ten cities along the way. After two weeks and nearly 1700 miles, the slain president would be laid to rest in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois.

For many spectators, it was as profound and magnificent as they had envisioned. But not for everyone. Letters and diaries from the spring of 1865 reveal another side of the experience. Mourners “roasted in the sun,” fainted in the crowds, and were “jammed almost to death,” as guards ruthlessly rushed them past the open coffin. Those who managed to linger a moment beside the body saw a face rapidly decomposing, unprotected by rudimentary embalming techniques.

The mobbed processions caused consternation, too. Pickpockets helped themselves to cash and watches. Men groped women. Drenching rain occasioned the lifting of thousands of umbrellas. Descending darkness obscured the majestic catafalque, and the bands played too softly for many to hear the music.

Nor did all mourners behave as other mourners wanted them to. “There was nothing solemn or touching in the whole thing,” a New York City viewer scoffed, noticing “gaily dressed” women with “smiling faces.” People laughed at dawdling marchers. Boys cheered when the presidential carriage finally came into view. For a woman watching the Philadelphia procession, it was “entirely ludicrous,” the whole thing a “superficial, irreverent farce.”

Bigger troubles intruded, too. Officials tried to block African Americans from joining the parades, and guards directed black people to the ends of lines. Irish mourners fought with African Americans, and Protestants ridiculed Catholics and Jews.

Nor did the shocking assassination bring together Union and Confederate. Vanquished southerners who read about the funeral train in the newspapers found the whole display disgusting, all “gas & bombast,” with Yankees hauling Lincoln’s “miserable old carcass” all over the country. In turn, many of Lincoln’s mourners looked beyond Booth to hold the entire Confederate leadership and the institution of slavery responsible for the crime.

Far from uniformly awe-inspiring, the disappointments of President Lincoln’s funeral portended tremendous conflicts for the newly reunited, but utterly unreconciled, post-Civil War nation.

Martha Hodes is a Professor of History at New York University, and the author, most recently, of Mourning Lincoln. Her other books include The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth-Century and White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the Nineteenth-Century South.

Martha Hodes is a Professor of History at New York University, and the author, most recently, of Mourning Lincoln. Her other books include The Sea Captain’s Wife: A True Story of Love, Race, and War in the Nineteenth-Century and White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the Nineteenth-Century South.

July 27, 2015

“Closing” Japan

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

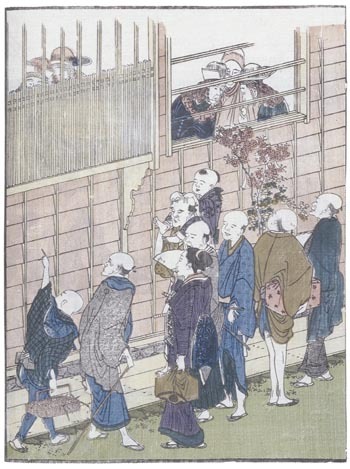

Curious Japanese watching Dutchmen on Dejima Island

In 1853 , Commodore Matthew Perry and his squadron of four “black ships of evil mien” opened Japanese ports to trade with the United States, a literal example of “gunboat diplomacy”. Most historically literate Americans are aware of Perry’s expedition in broad terms, even if they don’t know any of the details. Western accounts of Perry’s success treat it as a major step for both the United States and Japan’s development as modern powers, a triumph of modernity over traditional culture, a triumph of free trade over protectionism. Popular accounts of Japanese history treat it as the first step in the Meiji Restoration.

These accounts generally slide over the question of how, when, and why Japan was “closed”–itself an interesting episode in early east-west relationships.

As in India, the first Europeans to reach Japan were the Portuguese, who reached the islands by accident when a ship was blown off course in a storm in 1543. Soon Portuguese merchants were trading Western firearms and Chinese silk for Japanese copper and silver . At the same time, Portuguese and Spanish missionaries converted hundreds of thousands of Japanese, including at least six feudal lords, to a form of Catholicism that was filtered through Buddhist concepts.

The arrival of Europeans to Japan coincided with a period of political upheaval in Japan, known as the period of the Warring States. In 1600, the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated his rivals, using modern Western weapons such as cannon and muskets. He declared himself shogun, the first of the dynasty of Tokugawa shoguns who would rule in the name of puppet emperors for more than two hundred years.

Ieyasu immediately moved to consolidate his power. He disarmed the peasants and decreed that only members of the samurai warrior class would be allowed to carry swords. More important in terms of Japan’s relationship with the outside world, he ordered the country closed to Europeans. Christianity was outlawed and the missionaries were expelled. Tens of thousands of Japanese Christian converts were killed.* Trade with Europe was limited to the Dutch East India Company, which was allowed to dock once a year at the man-made and closely guarded island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor. After 1639, no Japanese were permitted to go abroad, Japanese ships were forbidden to sail outside Japanese waters and any Japanese sailor caught working on a foreign ship was executed.

Closing the ports against “contamination” by Western ideas is often presented as evidence of Japanese backwardness. After all, the Japanese missed the Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the rise of the middle class. On the other hand, during much of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan enjoyed a period of peace and order, secure from being taken over by Western powers. And as we’ll see in a future post, once the doors were open, Japan was quick to catch up.

*This was not a simple case of martyrdom, nor is it parallel to the Roman response to Christians. In 1637, Japanese peasants in Shimbara Peninsula rebelled against heavy taxation and abuses by local officials. Because most of the peasants in the region had converted, the Shimbara Rebellion soon took on Christian overtones. In one of the ironies with which history is rife, the Japanese government called in a Dutch gunboat to blast the rebel stronghold.

July 25, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Weird History of the Written Word

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

It is an undisputed fact that the written word and its many innovations and incarnations have repeatedly changed the course of history. So today’s Cabinet of Curiosities is devoted to the history of the written word in all its forms from the handwritten letter, to the printed book, and even the modern text message.

From Stone Mail to Snail Mail

If you had to carve your letters in stone, you would probably be a little more selective in what messages you sent. Imagine how angry the writer of the world’s oldest customer complaint letter must have been! Dating from 1750 BC, the complaint carved in stone came form an unsatisfied copper ore customer named Nanni who had sent messengers through a war zone looking for a refund. Now that’s one dissatisfied client!

If you had to carve your letters in stone, you would probably be a little more selective in what messages you sent. Imagine how angry the writer of the world’s oldest customer complaint letter must have been! Dating from 1750 BC, the complaint carved in stone came form an unsatisfied copper ore customer named Nanni who had sent messengers through a war zone looking for a refund. Now that’s one dissatisfied client!

What can rival a customer complaint etched in stone? A letter from the enemy might give it a run for its money. The letter in question is probably not what you are imagining. In 1922, the grieving mother of a fallen WWI pilot, Sallie Maxwell Bennett, received a letter from a German officer who had fought against her son. The unexpected letter recounts Louis Bennett’s extraordinary bravery and skill up until his death, and expresses uncommon admiration from his former foe.

Like many historians, you may wonder how today’s prevalent yet abridged emails and text messages will change how future generations understand our history. Playing on this idea, The New Yorker has imagined how some famous historical exchanges might have been different with smartphones. If you’re in the mood for a chuckle take a look at these humorous historical rewrites, such as how Paul Revere’s message might have gone wrong in the texting era.

Like many historians, you may wonder how today’s prevalent yet abridged emails and text messages will change how future generations understand our history. Playing on this idea, The New Yorker has imagined how some famous historical exchanges might have been different with smartphones. If you’re in the mood for a chuckle take a look at these humorous historical rewrites, such as how Paul Revere’s message might have gone wrong in the texting era.

The Bastion of the Written Word

Humankind has recognized the importance of writing since early on, and the need to protect and disseminate it. Hence, the library was born. Bibliophiles worry that the library is an institution doomed by the digital age, but where did libraries come from in the first place? A new tongue-in-cheek article 8 Weird Facts From the History of the Library gives us some highlights of the development of the library. For example, did you know the first public library was probably started by “one of Plato’s trashier students” (their words, not ours!).

Once you open a resource to the public, one of the chief concerns is how to protect it. Today we have barcodes and RFID tags, but how did they protect the precious commodity of books in the Middle Ages? The title of Medieval Books recent article Chain, Chest, Curse: Combatting Book Theft in Medieval Times gives you an idea. Books were so valued and so expensive to replace, that Medieval libraries literally had books chained to the shelves, or chests. However, the curses against thieves written inside many tomes served as a second line of defense.

Once you open a resource to the public, one of the chief concerns is how to protect it. Today we have barcodes and RFID tags, but how did they protect the precious commodity of books in the Middle Ages? The title of Medieval Books recent article Chain, Chest, Curse: Combatting Book Theft in Medieval Times gives you an idea. Books were so valued and so expensive to replace, that Medieval libraries literally had books chained to the shelves, or chests. However, the curses against thieves written inside many tomes served as a second line of defense.

If you have enjoyed reading a bit about the history of the written word, check out some similar recent posts on Wonders & Marvels:

How I Write History…with Dronfield and McDonald

July 24, 2015

Talking to the Beyond through the Luminiferous Ether

By Natasha Pulley (Guest Contributor)

Clairvoyance today is a bit unfashionable. In the nineteenth century, though, it was booming. Seances weren’t only the province of circus attractions and little stripy side tents at fairs but of the great stages and salons of London, something we still often see portrayed in fiction.

But it sounds like an odd sort of thing to happen — especially considering that some of the people who believed in it all most fervently were some of the cleverest and most analytical in the world. Arthur Conan Doyle believed it; Oliver Lodge, one of the first BBC science broadcasters, believed it. There was a Society for Psychical Research. It’s easy to think that perhaps, with all the baffling new science going on in ordinary life, people wanted a way to escape. In fact it was part of the new science.

But it sounds like an odd sort of thing to happen — especially considering that some of the people who believed in it all most fervently were some of the cleverest and most analytical in the world. Arthur Conan Doyle believed it; Oliver Lodge, one of the first BBC science broadcasters, believed it. There was a Society for Psychical Research. It’s easy to think that perhaps, with all the baffling new science going on in ordinary life, people wanted a way to escape. In fact it was part of the new science.

It really began with Newton, who said in his Optics that light must have a medium to move through — exactly like sound and air. This medium was the luminiferous ether. If you had an ether vacuum, you would have a patch of total darkness. Since there’s nowhere light-resistant, it follows that ether is everywhere, an all-permeating, immensely subtle substance that transports light at hundreds of thousands of times the speed of sound. Everything: space, stars at the far end of the universe, inside the human brain.

Newton was using the idea to explain light diffraction, but it came under intense focus again in the nineteenth century, fueled by new studies in electromagnetism. Although the mathematical models of the universe fluxed a great deal during this period, one of the few things they all agreed on was that the luminiferous ether must exist.

These models of an ether-seeped universe proved that clairvoyance could be real. The ether was everywhere and could go through anything. Things moving through it — light waves for a start — moved incredibly fast. There was nothing to say that it could not also transport the impulses of human thoughts beyond the human cranium. For the first time, science had provided a medium through which the thoughts of the dead, thoughts of the living, and perhaps other things altogether, might have been preserved.

In 1887, two scientists in America, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, conducted an experiment to prove the existence of ether. It was one of the most significant failures in scientific history, though it did provide important findings about the speed of light. But while it was a blow to ether theory, their experiment by no means destroyed it.

Mathematical models continued to use ether right up to 1905, when Einstein’s special theory of relativity negated the logical need for it. Einstein, though, never shouted about it. His mentor was a great proponent of ether theory. The idea isn’t quite gone even today; we still talk about things floating about in the ether.

Natasha Pulley studied English Literature at Oxford University and earned a creative writing MA at the University of East Anglia. Pulley lives near Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. The Watchmaker of Filigree Street is her first novel.

Natasha Pulley studied English Literature at Oxford University and earned a creative writing MA at the University of East Anglia. Pulley lives near Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. The Watchmaker of Filigree Street is her first novel.