Holly Tucker's Blog, page 28

July 10, 2015

Digging the Dirt in French and California Wines

By Thomas Parker (Regular Contributor)

In vino veritas means “in wine there is truth.” Most of us take that to be a truth about ourselves and not wine, but imagine if by drinking wine you could taste truth literally, unlocking some mystery transmitted to the grapes from the soil they grew in. Now imagine if standing between you and that truth there was a cloying, syrupy mound of sweetness, enveloping it like a shroud, so that you had to lift it away to get at it.

That was at the essence of a recent article in the New York Times Magazine, entitled the “Wrath of Grapes,” which described how Rajat Parr and a group of like-minded California winemakers are bucking the practice of producing fruity, alcoholic wines.

These nonconformists harvest grapes that are less ripe with lower sugar, claiming to make wines lower in alcohol and more balanced than those of their neighbors. These wines, as their logic goes, avoid the blasting doses of fruit that would overshadow a wine’s more subtle aspects.

As s uch, the products are more representative of the land, or the “terroir” that they are produced on. Terroir, a French word derived from the Latin terra for “earth”, is used by enthusiasts to describe the effect that the geographic origin of a food or wine (and the quantity of sunlight, qualities of soil, rainfall, drainage, etc.) have on its flavors. If there is similarity between the expectations for the flavors typically produced in a specific place and the actual flavors produced by a wine or food, the latter is thought to be a pure, natural, and authentic expression of the terroir it was grown on.

uch, the products are more representative of the land, or the “terroir” that they are produced on. Terroir, a French word derived from the Latin terra for “earth”, is used by enthusiasts to describe the effect that the geographic origin of a food or wine (and the quantity of sunlight, qualities of soil, rainfall, drainage, etc.) have on its flavors. If there is similarity between the expectations for the flavors typically produced in a specific place and the actual flavors produced by a wine or food, the latter is thought to be a pure, natural, and authentic expression of the terroir it was grown on. The conversation comparing ripe, fruity wines to more subdued terroir wines is interesting in itself but also demonstrates how arbitrary such terms as “pure and “authentic” have historically been in the context of food appreciation. Going back three hundred and fifty years in France to the court of Louis the XIV, for example, things were much different. Instead of constituting purity, terroir was the term used to designate “impurity.” It was a blemish of the earth conveyed by the imperfections of a particular place that a food came from.

The conversation comparing ripe, fruity wines to more subdued terroir wines is interesting in itself but also demonstrates how arbitrary such terms as “pure and “authentic” have historically been in the context of food appreciation. Going back three hundred and fifty years in France to the court of Louis the XIV, for example, things were much different. Instead of constituting purity, terroir was the term used to designate “impurity.” It was a blemish of the earth conveyed by the imperfections of a particular place that a food came from.

Connoisseurs sought out foods that did not smell of terroir, and built their reputations on being able to detect flaws in foods “corrupted” by the terroir of their origin. Food smelling of the terroir was not a positive trait, as Parr would have it, but an imperfection, contaminating the essence of the fruit.

This anecdote shows how historically bounded characterizations such as “pure” and “natural” are in terms of food, but even more surprising how these terms often originate outside the world of cuisine all together. In the above example, seventeenth-century French food customs evolved from a reflection on the purity of the French language and the broader structures of political and social power that shaped it. Within the prestigious ranks of Louis XIV’s court society, people sought to speak without a provincial accent. Those who betrayed provincial origins were said to be unrefined interlopers in the court, “smelling of the terroir.”

This anecdote shows how historically bounded characterizations such as “pure” and “natural” are in terms of food, but even more surprising how these terms often originate outside the world of cuisine all together. In the above example, seventeenth-century French food customs evolved from a reflection on the purity of the French language and the broader structures of political and social power that shaped it. Within the prestigious ranks of Louis XIV’s court society, people sought to speak without a provincial accent. Those who betrayed provincial origins were said to be unrefined interlopers in the court, “smelling of the terroir.”

The attitude toward language became reflected in tastes in food and wine. People attempted to demonstrate their personal refinement and purity by s eeking out the so-called “purest,” most neutral, and most “natural” foods: those showing only unadulterated fruit, untainted by any characteristic of the terroir.

eeking out the so-called “purest,” most neutral, and most “natural” foods: those showing only unadulterated fruit, untainted by any characteristic of the terroir.

Let us compare this phenomenon to the stigma placed on regional accents today in the United States. Mostly, people don’t wish to possess a Brooklyn accent, a Jersey accent, a Southern accent or a Midwestern accent. People don’t want their spoken tongues to reflect the terroir and, until recently, most didn’t ask for that in the taste of their wines either.

Thomas Parker is our newest Regular Contributor at Wonders & Marvels. He teaches French and Francophone literature at Vassar College, and has an extensive background in wine. He took a year off to work in Champagne, France while in college, and then worked for an importer while managing a wine store before going back to graduate school. His latest book, Tasting Terroir: The History of an Idea (University of California Press, Berkeley), was published in 2015.

Thomas Parker is our newest Regular Contributor at Wonders & Marvels. He teaches French and Francophone literature at Vassar College, and has an extensive background in wine. He took a year off to work in Champagne, France while in college, and then worked for an importer while managing a wine store before going back to graduate school. His latest book, Tasting Terroir: The History of an Idea (University of California Press, Berkeley), was published in 2015.

July 9, 2015

Ibn Who?

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

Ibn Khaldun on the Tunisian 10 dinar note. Image courtesy of http://www.banknotes.it

If you spend any time studying history in a serious way–whether in school and/or as a dedicated history nerd–you end up with a list in your head of Great Historians of the Past: Herodotus, Thucydides, Tacitus, the Venerable Bede, Gibbon, Macaulay, Prescott. Even after their historical works were revised or even rejected by later scholars, they remain as monuments of thought, analysis, and masterful story telling.

I had finished my graduate school coursework and was well into my dissertation before I added fourteenth century Arab historian and social observer ibn Khaldun to my personal list of history all-stars.

Ibn who? I thought you’d never ask.

Ibn-Khaldun is sometimes seen as the last great scholar of the Islamic golden age, now considered by those in the know as one of the founders of modern historiography, sociology, and economics. He was born in Tunis in 1332 to an Andalusian family of scholars and officials who had fled Spain after Seville fell to Ferdinand of Castile in 1248. ( NOT the Ferdinand of Ferdinand and Isabella. The Christian reconquest of Spain took several centuries. ) When he was seventeen, his parents and teachers died in the Black Death, as did almost half the population of Europe and Asia.

Like many others caught in the chaos that followed the Black Death, ibn Khaldun left his home in search of something: stability, a career, adventure, a life. He was well educated and had no trouble finding work in the courts of North Africa and Islamic Spain. Although he claimed that he wanted to devote his life to scholarship, he repeatedly became entangled in court intrigues thanks to either bad luck or bad judgment.

In 1375, after he failed to save a friend who was tried and executed for heresy, ibn Khaldun withdrew to the Castle of ibn Salamah, near Oran in Algeria, to immerse himself in his books and try to make sense of his experiences. During his years of retreat, he completed what would be his best-known and most original work: the Muqaddima, or Prolegomenon. Intended as the first volume of history of the Arab peoples, the Muqaddima is an introduction to the writing of history and a discussion of the nature of the state and society. In it, he explores the idea that writing history is an act of interpretation and suggests a rigorous process of fact checking as a necessary part of the work.

The most important part of the book is the Islamic equivalent of Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Drawing on his personal and family experience and the history of the Arab world, ibn Khaldun analyses how civilizations breed their own decline, moving from strength to luxury to moral laxity and decay. Historian Arnold Toynbee, himself the author of a twelve-volume study of the rise and fall of civilization, described the Muqaddima as “undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever yet been created by any mind in any time or place…the most comprehensive and illuminating analysis of how human affairs work that has been made anywhere.”

After four calm years at the Castle of ibn Salamah, ibn Khaldun needed conversation and a research library so he could work on the main body of his history. He returned to Tunis, where he was immediately sucked into the usual morass of academic, religious and political intrigues. He escaped Tunis under the pretext of going on the hajj, only to fall into similar turbulence in Cairo. Over the course of twenty-five years, the sultan appointed him as a judge and subsequently dismissed him six times.

In 1400, ibn Khaldun was given another chance to help write history, this time as a source. The sultan of Cairo insisted that he join a delegation to Damascus to negotiate with the renowned Mongol conqueror, known in the west as Tamurlane. When the delegation received word of the rebellion back in Cairo, they returned to the west, leaving ibn Khaldun behind in the besieged city of Damascus. The historian was determined to meet with the renowned conqueror. Since the gates of the city were locked, he had himself lowered over the walls in a basket. Ibn Khaldun met with Timur several times over the course of the month, enjoying wide-ranging conversations about history, North African culture and Timur’s conquests. Ibn Khaldun recorded those conversations, as well as a first hand account of the siege of Damascus in his autobiography, now a major resource for anyone writing about Timur.

Ibn Khaldun returned in Cairo in 1401 and resumed the cycle of appointment and dismissal. He died there five years late.

A version of this post previously appeared in History in the Margins

Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change. She is the author of Mankind: The Story of All of Us–a companion book to the History Channel series.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in November 2012.

July 8, 2015

Museum Mysteries: The Mummy in the OR

By Sarah Alger (Regular Contributor)

When, in the early 1800s, a patient was brought into the surgical amphitheater at Massachusetts General Hospital, he or she was likely blinded by the terror of undergoing surgery fully conscious. Yet had the patient looked around, while being lashed to a chair, he or she might have taken in the cupola and louvered windows admitting the morning sun; a gathering of physicians, medical students and other onlookers in the tiered seats; the surgeon preparing his instruments; and a pair of upright glass-fronted cases, one containing an Egyptian mummy coffin, and the other, the mummy himself.

Padihershef and his inner coffin underwent extensive conservation in 2013.

How did the mummy come to be there? In 1823 he was given by a Dutch merchant to the city of Boston, which in turn gave him to the hospital for fundraising purposes. The hospital duly shipped out the mummy for a tour of the Eastern seaboard, reaching as far south as Charleston. People paid 25 cents to see the mummy, the first complete Egyptian burial ensemble in the United States. In 1824 he returned to the hospital, where the trustees deemed him “an appropriate ornament of the operating room.”

Head surgeon and hospital co-founder John Collins Warren was the first of many at the hospital to explore the mummy’s mysteries. In the operating room before a crowd, Warren cut away the wrappings around the head, but chose to go no further, instead visually inspecting the rest of the body and the inner and outer coffins, and going on to publish a detailed description in the Boston Journal of Philosophy and the Arts. Warren surmised that the man had been a priest, but much mystery remained.

It was not until 1960, when an Egyptologist at the Museum of Fine Arts examined the coffins’ hieroglyphics, that the mummy’s name was revealed: Padihershef, meaning “gift of the god Hershef.”

As imaging technology came into existence and advanced, so it was applied to Padihershef. He was first X-rayed in 1931, then in 1976. During that later session, radiologists discovered some neck vertebrae missing, leading them to wonder how the mummy’s head was staying on. In 2013, when Padihershef underwent extensive conservation and CT imaging, it was discovered that a broom handle was holding his head on, a fix attributed to a conservator in 1984 at another museum, where Padihershef resided for a while.

Egyptologist Jonathan Elias analyzed Padi after the 2013 conservation, and though his report holds a number of fascinating observations, perhaps the most evocative one is about Padihershef’s occupation. He was not a priest, but rather, according to the hieroglyphics, a stone mason:

“On balance, our general interpretation of his occupation must move away from heavy manual activity in the field of ‘stone masonry,’ and any images conjured up by that term. We should begin to view Padihershef instead as a sort of prospector amongst the tombs in western Thebes, and as the kind of person who would scramble up and down the rocky slopes of the Theban necropolis in an effort to identify opportunities to carve out fresh burial space amidst the myriad empty chambers, crags and crevices.”

It is now this image I’ll hold when I regard Padihershef, who still watches over our original operating room.

Sarah Alger is our newest Regular Contributor at Wonders & Marvels and she will be writing our new column Museum Mysteries. She is the director of the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital. She is also senior editor of Proto, a Mass General-sponsored magazine that covers new ideas in basic and clinical research, health policy and technology the world over. She tweets as @slodoena.

July 7, 2015

History is Sometimes Made by Great Men (and Women)

By Matthew Cobb (Guest Contributor)

Writing history is always weird, because we know the way that things happened. And there were lots of ways in which events could have taken off in a different direction. Random events can be the hinge of fate, as Churchill put it.

The history of science is even odder than ‘ordinary’ political, military or social history. Not only did the history of a particular discovery only take one route, but because science is – or at least claims to be – progressive and coherent, building on previous discoveries, it is tempting to think that the way great scientific discoveries took place was more or less pre-determined and inevitable.

And the history of science, perhaps even more than other forms history, is full of Great Men (they normally are men) and their doings.

As a result, the history of science – especially when written by scientists – tends to be a tale of brilliant individuals pitting their intelligence against some major problem and then eventually cracking it, thereby changing the way we view the world.

When writing my new book on the history of the race to crack the genetic code, Life’s Greatest Secret, I found myself torn between two approaches. On the one hand, I wanted to show how the way we think about genes and heredity was changed not only be discoveries, but above all by ideas.

When writing my new book on the history of the race to crack the genetic code, Life’s Greatest Secret, I found myself torn between two approaches. On the one hand, I wanted to show how the way we think about genes and heredity was changed not only be discoveries, but above all by ideas.

So the starting point was a sentence written by Jim Watson and Francis Crick in a paper they published in Nature in May 1953, in which they stated ‘the sequence of the bases is the code that carries the genetic information’. To any modern student of biology, this looks completely obvious – genes contain information, that is represented by a code made of by a sequence of chemicals in DNA called bases.

But in May 1953, no one had ever strung those ideas together before. No one had ever spoken of ‘genetic information’, and although the idea of a genetic code had been around for 10 years, it had not been taken seriously by geneticists.

I had to trace the origin of these ideas, and found them not in biology but in the history of computing and mathematics and cybernetics, in the work of Norbert Wiener, Alan Turing and Claude Shannon.

This social context shows where the ideas came from, but it does not explain how they were melded together into such a pithy phrase.

And that turned into the second thread of the book, as I described the work done by a huge network of scientists in the period 1953-1967 as they collaborated and competed in the race to crack the genetic code.

One name kept on popping up, that of Francis Crick. As I carried out the research and wrote the book, Crick’s incisive mind repeatedly amazed me. His insights, his boldness, his intuitions drove forward our understanding of the genetic code, and acted as a thread running through the book.

One name kept on popping up, that of Francis Crick. As I carried out the research and wrote the book, Crick’s incisive mind repeatedly amazed me. His insights, his boldness, his intuitions drove forward our understanding of the genetic code, and acted as a thread running through the book.

Naively, I had initially wanted to write a social history of the genetic code, showing the interactions between different ways of thinking about the world. But I had to introduce the human factor – the individuals who did the work, their hopes and their fears, their sometimes scandalous behavior. And through all this, Francis Crick’s intelligence shone and enthralled me.

The history of the genetic code could easily have taken place in a different way. Had Crick been run over by a bus in 1950, the code within the double helix would still have been discovered – Rosalind Franklin appreciated its significance, even as she and Maurice Wilkins were both scooped by Watson and Crick.

But the way that the code was cracked, the ideas that swirled around this research in the 1950s and 1960s, that would have been very different, and almost certainly poorer.

If readers wish to know more about the Crick/Watson/Franklin/Wilkins double helix story (which is not the focus of the book), they can read this article:

Matthew Cobb is a Professor of Zoology at the University of Manchester, where he works on insects and on the history of science. He lives in Manchester, England.

Matthew Cobb is a Professor of Zoology at the University of Manchester, where he works on insects and on the history of science. He lives in Manchester, England.

W&M is excited to have five (5) copies of Life’s Greatest Secret in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on July 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaway

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

July Book Giveaways

Maureen Gibbon, “Paris Red”

Matthew Cobb, “Life’s Greatest Secret”

July 6, 2015

The Many Lives of the Dartford Manor Gatehouse

By Nancy Bilyeau (Guest Contributor)

In the town of Dartford, a 40-minute train ride south of London Charing Cross, stands a building called the Manor Gatehouse. Inside you will find a registration office to record the births, marriages, and deaths that occur in Kent. This handsome red-brick building, fronted by a garden, is also a popular place to throw a wedding reception.

But as I looked at the Gatehouse one day, I thought about who stood on this same piece of ground five centuries ago. Because it was then a Catholic priory—a community of women who constituted the sole Dominican order in England before the dissolution of the monasteries. And the priory is where I chose to tell the story of my novels.

But as I looked at the Gatehouse one day, I thought about who stood on this same piece of ground five centuries ago. Because it was then a Catholic priory—a community of women who constituted the sole Dominican order in England before the dissolution of the monasteries. And the priory is where I chose to tell the story of my novels.

There are all sorts of ways to write historical fiction. The books can range from reimagined stories of famous people of the past, such as novels written by Philippa Gregory and Conn Iguldden, to tales of purely imagined characters in a different time, such as Cold Mountain and The Historian (although Dracula may at this point seem as familiar to us as Great-Uncle Vlad, he was never alive—or undead!).

In my trilogy, the main character, Sister Joanna Stafford, is fictional. As are Geoffrey Scovill, Brother Edmund, Brother Richard, Sister Agatha and many more of the secondary characters. But Lady Margaret Bulmer, whose burning at the stake for treason begins The Crown, did exist. So did Bishop Stephen Gardiner; Sir William Kingston; Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and his children, Mary Howard, Dowager Duchess of Richmond, and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey; Dartford’s Prioress Elizabeth Croessner; Malmesbury’s Prior Roger Frampton; Henry and Gertrude Courtenay, the Exeters; Sir Walter Hungerford; Hans Holbein the Younger; and let’s not forget Thomas Cromwell. And then comes the A-list of the Tudor court: Katherine of Aragon and her daughter Mary, Anne and George Boleyn, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard, and of course, the rock star himself, Henry VIII. They’re very much in the mix of my three novels.

Why did I not confine myself to imaginary creations of the late 1530s and early 1540s? The truth is because as much as I loved crafting my own characters, the real people were irresistible. I’ve been reading about them and thinking about them since I was a teenager. So when the time came for me to write my books, there was just no way that they wouldn’t be invited to the party.

In 2012 I spent a week in London and Dartford. It took me five years to research and write the first novel in the series, The Crown. I worked away in New York City, where I’ve lived for a long time. I often sought inspiration in the Cloisters Museum of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But nothing can substitute completely for the real place, even if the “real” place existed centuries ago.

I spent nearly every waking hour running around London. You have only to take a tour of the Tower of London given by a dry-witted yeoman warder or peek into the Tower gift shops (yes, plural; I counted three) to know that this is a place that mines its history well. The Tudors, the Plantagenets, the Stuarts, the Hanovers and the present House of Windsor… the gang’s all here, each with a fascinating—if a trifle well worn—story to tell.

My day in Dartford awakened different emotions. The priory was a vital part of the town’s life for 180 years. It was torn down after its prioress reluctantly surrendered to the will of King Henry VIII, who destroyed the abbeys and priories of England in his break from Rome. That dissolution is a key part of the plot to my books.

My day in Dartford awakened different emotions. The priory was a vital part of the town’s life for 180 years. It was torn down after its prioress reluctantly surrendered to the will of King Henry VIII, who destroyed the abbeys and priories of England in his break from Rome. That dissolution is a key part of the plot to my books.

The Gatehouse you see today, the one that today offers charming wedding packages, did not exist during the time of the nuns. It was raised shortly after the sisters were expelled. King Henry VIII demolished the priory and built a very expensive manor house for himself. He never slept there, although his least troublesome ex-wife, Anne of Cleves, did. Years later, Anne’s stepdaughter, Elizabeth I, did too. It was exciting to see it and I pleaded with the woman who runs the registration office to snap my picture in front of the Gatehouse’s main entrance.

But the only physical evidence left of the house of Dominican nuns is the stone wall that ran along the property’s perimeter. On a cloudy July afternoon I walked it as the cars whizzed by, and I felt humbled. I had researched priory life, with the help of many books and articles and the guidance of the wonderful staff at Dartford Borough Museum, located near the center of the town. I knew something of the ritual of their daily lives.

Joanna Stafford may not be real. But nuns and novices and prioresses and friars took vows at Dartford, they lived and worshipped and sang and laughed and suffered and died on the other side of this 600-year-old wall. There are no mugs bearing their faces on sale at any gift shop. But their lives were significant all the same. I paid them silent homage in my solitary walk.

And I hope in my small way I’ve done them justice.

Nancy Bilyeau, author of The Crown and The Chalice—an O, The Oprah Magazine pick in 2012 and a 2014 RT Book Reviews Best Historical Mystery respectively—is a writer and magazine editor who has worked on the staffs of InStyle, Rolling Stone, and Good Housekeeping. She is currently executive editor of DuJour magazine. A native of the Midwest, she graduated from the University of Michigan and now lives in New York City with her husband and two children.

Nancy Bilyeau, author of The Crown and The Chalice—an O, The Oprah Magazine pick in 2012 and a 2014 RT Book Reviews Best Historical Mystery respectively—is a writer and magazine editor who has worked on the staffs of InStyle, Rolling Stone, and Good Housekeeping. She is currently executive editor of DuJour magazine. A native of the Midwest, she graduated from the University of Michigan and now lives in New York City with her husband and two children.

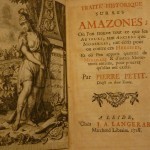

Proving the Existence of Amazons, 1685

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Were Amazons real or imaginary? If warrior women did exist in antiquity, was their society exclusively female? In 1685, the French scholar-physician Pierre Petit (b. 1617) set out to prove the reality of warrior women, known as Amazons. Petit’s treatise was published and reprinted in French and Latin, 1685-1718. I had the good fortune to consult a French edition of “Traité historique sur les Amazones” in the Getty Museum’s rare book collection. Petit’s subtitle of “Historical Treatise on the Amazons” explains that he “considers all the authors, ancient and modern who have written for or against the existence of these heroines, and presents many ancient coins and artworks as evidence to prove that they did exist.”

Were Amazons real or imaginary? If warrior women did exist in antiquity, was their society exclusively female? In 1685, the French scholar-physician Pierre Petit (b. 1617) set out to prove the reality of warrior women, known as Amazons. Petit’s treatise was published and reprinted in French and Latin, 1685-1718. I had the good fortune to consult a French edition of “Traité historique sur les Amazones” in the Getty Museum’s rare book collection. Petit’s subtitle of “Historical Treatise on the Amazons” explains that he “considers all the authors, ancient and modern who have written for or against the existence of these heroines, and presents many ancient coins and artworks as evidence to prove that they did exist.”

Petit’s approach was practical and rigorous, based on all the literary and archaeological evidence available in the 17th century. He included maps and numerous woodcuts of medals, coins, and statues of Amazons. Some of the medallions he believed to be authentic Greek antiquities were neo-classical fakes, however, especially those showing Amazons with only one breast, something that no ancient artist depicted.

Petit began by gathering all the known Greek and Latin sources describing Amazons. Logic, he declared, requires that the sheer number of ancient reports and images of various warrior women in barbarian lands should be taken seriously. Next he dismissed the idea one must assume that Amazons were a society of women only. It was this false notion, he wrote, that had led people to reject the existence of Amazons. He cited the description by Hippocrates (5th century BC) of steppe nomad women who rode, shot bows, and made war alongside their men. Petit also remarked that contemporary European travelers had observed warlike women in modern cultures.

Petit then addressed the 1st century BC geographer Strabo’s skepticism, in which he compared the notion of Amazons to an impossible inversion, in which “men would have to be women and women would become men.” But, as Petit pointed out, Strabo’s doubts were grounded in biological determinism and arose from what we would call gender bias.

Indeed, Petit’s arguments and conclusions are surprisingly modern. “Who can deny,” he wrote, “that women have the same nature as men? Since we cannot deny this natural equality, it follows that God endowed both sexes with the same ability to reason and act.” Therefore, he concluded, women, like men, are capable of giving counsel, making decisions, governing, and fighting.

July 4, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Picture This!

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Those of us who teach, write, or research history are always looking for ways to bring the past to life, whether for our students, readers, or ourselves. This week we are looking at some wonderful and wacky high and low-tech ways to visualize history.

It’s Visual Dude!

If you think the exclamation “Dude!” is a modern, or semi-modern, form of slang, think again. This fun video by Arika Okrent details the etymology and evolution of the word “dude” with live illustrations of dude’s various meanings. From Hipsters of the 1880s to the perhaps overused emotive dude of the new millennium, this video makes historical linguistics more accessible to every dude than ever before.

Do you wish you could walk through the most beautiful archaeological sites in the world in a matter of minutes? From Cambodia to the Sudan with one click, it is possible to visit sites like the Nubian pyramids with the drone tours of Ancient sites. The relatively small size of the drones allows viewers to experience both the aerial view and up-close details of these world wonders in a matter of minutes.

July 3, 2015

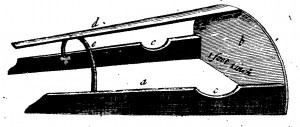

Saving Babies the Arcutio Way

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

Parents of infants are obsessed with sleep. Is the baby a good sleeper? Will the parents ever sleep again? But in particular, the spectre of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome) haunts all new parents… causing panic when the baby finally does sleep through the night. Although the campaign to have babies sleep on their backs has led to a significant decline in cases since the 1990s, a more controversial recommendation by many health authorities is that parents not sleep with their infants to prevent suffocation or over-heating; but if they do, the bed should be firm and free of pillows and heavy bedding. Supporters often discuss bed-sharing as a natural activity or the historical norm, but the debate over bed-sharing—and the discourse of what is natural—goes back a long way.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Bills of Mortality tallied the weekly causes of death in London. One classification was “overlaying”, which referred to the wetnurse or mother rolling on to a sleeping baby or the baby suffocating under the bedclothes. The numbers did not remain constant. To give just two examples: in one November week in 1719, there were no overlaying deaths, but in one December week in 1726, there were sixty-seven.

By 1731, there was a growing interest in preventing these deaths. Oliver St. John wrote to the Philosophical Transactions with a suggestion:

When I consider how many are charged overlaid in the Bills of Mortality, I wonder that the Arcutio’s, universally used at Florence, are not used in England. This would prevent infants from being smothered by bedclothes, even if they were completely covered over.

The Arcutio. Source: The Art of Nursing, 1733 (Eighteenth-Century Collections Online).

The device even had hollows for the nurse’s breasts, allowing her to breastfeed (c). Resting on a bar of wood (d) would keep her from falling onto the child and provide support. The arcutio could safely allow nurses and mothers to follow their natural preference to breastfeed in bed.

According to St. John, every nurse in Florence was obliged to use one, under pain of excommunication. This assertion was corrected in an article on “The Arcuccio” in the British Medical Journal (10 August 1895). Italian priests did encourage their parishioners to use the devices, the author wrote, but “the use of the arcuccio is enforced partly by public opinion, which would judge very severely any mother whose child lost its life owing to failure to use a well recognised precaution.” Perhaps in an attempt to build up similar public support in England, St. John’s article was soon after reprinted as general advice towared the end of The Art of Nursing (1733).

Discussions of the arcutio as a solution largely disappeared until the nineteenth century, although it made an appearance in John Jones’ Medical, Philosophical and Vulgar Errors, of Various Kinds, Considered and Refuted (1797). Jones addressed the question of whether a white mother in the West Indies “must shew a great want of Affection” to let her child be suckled by a black wetnurse on the grounds that the nurse’s milk would be of poor quality. Jones believed that black wetnurses had excellent milk, but he suggested that because “they are more careless and less affectionate than the white,” they should always be encouraged to use arcutios.

A woman breast feeding her child. Stipple engraving, 1810. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Authors of eighteenth-century infant-rearing manuals provided contradictory advice about the threat of overlaying. In The Nurses Guide (1744), Thomas Dawkes insisted that infants should never sleep in the same bed as the mother or nurse “for fear of overlaying it, (a caution, I am afraid, not so often observ’d as ought to be).” Clearly many women continued to sleep with their babies rather than put them in cradles.

William Moss was an adamant supporter. In his Essay on the Management and Nursing of Children (1781), he claimed that young babies needed the warmth of “a common bed” for health and development, especially in the cold northern climate. That young children “will frequently make surprising efforts and attempts, when in bed with the nurse, to get near her” surely meant “it can be no other than an instinctive requisite, [which] ought to be indulged.” He dismissed the fear of overlaying:

if she has been accustomed to sleep with children; and is an accident that scarcely happens once in an age with those who have not been accustomed.

Moss contradicted the contemporary medical focus on strengthening constitutions by cold-bathing and exposure to cold air, but his advice tapped into the widespread midwifery practice of keeping new mothers and babies warm, as well as the eighteenth-century belief that nature always knew best.

The question of “natural” practices has long been at the centre of debates on bed-sharing. For Moss, overlaying rarely happened because bed-sharing was so natural: babies instinctively snuggled for heat and carers managed to avoid rolling on them. The arcutio was depicted as a useful device both in terms of overcoming nature (the carelessness of black wetnurses, according to Jones) and aiding it (ordinary breast-feeding behaviour, according to St. John). As the concern over saving babies the arcutio way reveals, although bed-sharing was a historical norm, the desirability of following one’s nature was no more clear than it is today.

July 2, 2015

Pompeii Myth-Buster

By Caroline Lawrence (Guest Contributor)

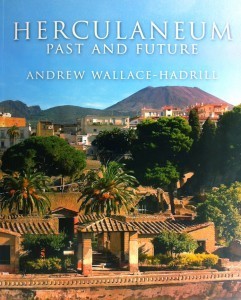

Pompeii buffs beware! If you go on a tour with Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill your world will be rocked as surely as the Pompeians were rocked on several occasions leading up to that fateful day in 79 CE when Vesuvius erupted. Wallace-Hadrill is director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project and author of Herculaneum: Past and Future. Some people call him “Professor Herculaneum”, because few people know Pompeii’s smaller, richer sister-city better.

Pompeii buffs beware! If you go on a tour with Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill your world will be rocked as surely as the Pompeians were rocked on several occasions leading up to that fateful day in 79 CE when Vesuvius erupted. Wallace-Hadrill is director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project and author of Herculaneum: Past and Future. Some people call him “Professor Herculaneum”, because few people know Pompeii’s smaller, richer sister-city better.

When Cambridge Alumni Travel in conjunction with Andante Travels offered a once-in-a-lifetime chance to visit ruins on the Bay of Naples with Wallace-Hadrill I jumped at the chance. I had visions of him telling us things no book would reveal and taking us places no tour guide would have access to. I was right. He did get us into places the other tours didn’t reach. But he also demolished some long-accepted facts about the famous eruption of Vesuvius and the ruins it left.

By the end of our first hour with Andrew Wallace-Hadrill I realized he was a Myth Buster extraordinaire. Like all great historians and archaeologists, he does not accept facts just because they’ve been repeated in print a bazillion times. He has a knack for looking at things with fresh eyes and reinterpreting the evidence if necessary.

Here are ten of my most cherished beliefs: BUSTED!

Myth #1 – Vesuvius Did Not Erupt on 24 August AD 79. Everybody confidently quotes this as the date of the eruption, but everybody is probably wrong! At the turn of the 20th century, everybody claimed the eruption occurred in November. But Wallace-Hadrill thinks late September or early October is a likelier date. His clue is a lot of ripe pomegranates found near a buried villa at a place called Oplontis between Pompeii and Herculaneum. (This villa is known as the Villa Poppea or Villa Poppaea because it was owned by Nero’s wife Poppaea.) In Italy, pomegranates ripen in late September/early October. The problem is not with Pliny the Younger, whose famous letters tell us the date of the disaster, but with the monks who interpreted his dates as they copied his manuscripts.

Myth #2 – Villa Poppea Not Owned by Nero’s Wife. The Villa at Oplontis probably wasn’t called the Villa Poppea and it probably wasn’t owned by Nero’s wife Poppaea. (Though both things might be possible.) Furthermore, the town where it’s located wasn’t called Oplontis. Or maybe it was. We just don’t know.

Myth#3 – Population of Herculaneum. Guide books often say the population of Herculaneum was 4,000 people. We simple do not know! Those who hung around were probably vaporized by the first pyroclastic surge. This explains why so few bodies have been found in the town at the foot of Vesuvius. The only bodies we’ve found at Herculaneum were those sheltering deep underground or in the vaulted boat-houses facing the waterfront. But wait…

Myth #4 – Not Boat-houses. The famous bone-filled “boat-houses” in Herculaneum probably weren’t boat houses. Yes, they were by the sea but they probably had a double function as foundations for the Suburban Baths and storehouses for various goods, (but probably NOT for boats.) Wallace-Hadrill thinks the dozens of skeletons found there were those of people sheltering from what they believed was just another earthquake. He believes there were dozens of earthquakes in the run-up to the eruption, starting with the big one in 62 CE. But wait…

Myth #5 – The Earthquake of 62. The famous earthquake of 62 CE was almost certainly in 63 CE. Scholars got the dating wrong. Tacitus tells us who the consuls were and this allows us to date it precisely.

Myth #6 – Buried Under Hot Mud! Herculaneum was NOT buried by hot mud as all the guidebooks tell you. It was buried under alternating layers of tufa (hardened ash) and lapilli (light aerated pebbles of volcanic matter). You can see it before your very eyes if you just look.

Myth #6 – Don’t Call it a Thermopolium. The Romans called those fast-food places popinae or tabernae. The word thermopolium only occurs once in Plautus (a 3rd century BC Roman comic playwright). It was probably a joke word. Wallace-Hadrill, the Myth-Buster, called this a “dubious term”.

Myth #7 – Don’t Call it the Decumanus Maximus. Romans did not call the main road through town the Decumanus Maximus. That is a term invented by modern scholars. They probably called it Venus Street. Or Street of the Fishmarket, or similar.

Myth #8 – Don’t Call it a Lararium. They might have worshipped Hercules or Diana there, rather than the Lares of the household. Call it a shrine, an aediculum in Latin.

Myth#9 – So-called Discovery of Pompeii. Pompeii was not really “discovered” in the 18th century. They knew it was there but just weren’t interested or were discouraged by the church from investigating too deeply.

Myth#10 – The Erect Male Member is Not Always Apotropaic. In Pompeii, guides will tell you that phalluses point the way to brothels. Experts tell you the erect member was a symbol of good luck, used against the “evil eye”. But to bust a busted myth: sometimes the phallus DID point the way to a brothel. (see picture at top, of a phallus on a paving stone of the Via dell’Abbondanza, Pompeii’s main drag.)

The main thing I learned from our time with Professor Herculaneum was this: There’s a lot we don’t know. Don’t believe things just because you’ve read them or heard them. Always check the primary sources in conjunction with the archaeological evidence and make up your own mind.

The main thing I learned from our time with Professor Herculaneum was this: There’s a lot we don’t know. Don’t believe things just because you’ve read them or heard them. Always check the primary sources in conjunction with the archaeological evidence and make up your own mind.

For those of you not lucky enough to travel to the Bay of Naples with Andrew Wallace-Hadrill as a tour guide, don’t despair. His lavishly-illustrated and clearly-written book, Herculaneum Past and Future, is now out in paperback. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Caroline Lawrence has written a 17-book series of history-mystery books for children called the Roman Mysteries. Three of the books are set on the Bay of Naples during and after the eruption of Vesuvius: The Secrets of Vesuvius, The Pirates of Pompeii and The Sirens of Surrentum. Find out more at her website: www.carolinelawrence.com

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in February 2013.

July 1, 2015

Introducing Bric-a-brac-o-mania

By Rachel Mesch (Regular Contributor)

In novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans’ 1884 Against the Grain (À Rebours), the world-weary aristocratic protagonist Jean des Esseintes suffers from an acute case of fin-de-siècle ennui. He thus retreats into his estate on the outskirts of Paris, determined to live a solitary life of aesthetic contemplation.

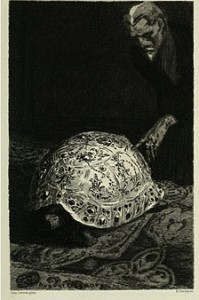

Des Esseintes has little trouble keeping himself entertained in his home, which is filled with well-chosen objects and custom décor: in addition to an extensive book collection in French and Latin and a caged cricket to remind him of his childhood, he has a built-in aquarium whose water’s colors can be altered to suit his aesthetic predilections, and a “liquid organ” that synesthetically matches tasty liquers to musical symphonies. In one of the novel’s most memorable episodes, the tortoise that Des Esseintes had purchased fails to sufficiently awaken the hues of the oriental carpet that the creature was meant to throw into relief. Frustrated, he has it glazed with gold and then with rare gems, only to discover, hours later, that the animal has died from the unnatural weight imposed upon his bejeweled carapace.

Illustration of the bejeweled tortoise from A. Ferroud’s 1920 edition of A Rebours

An eccentric character? Certainly. The product of a hyperactive literary imagination? No doubt.

But Des Esseintes’ sensual passion for decorative objects and interior design was actually so familiar to late nineteenth-century life that numerous of Huysmans’ colleagues were credited with being the inspiration for the fictional character—including Charles Baudelaire (whose poetry adorns the character’s bedroom). Certain descriptions of Des Esseintes’ home were likely based upon the residence of dandy extraordinaire Robert de Montesquiou, whose own abode had a “moon room” meant to inspire new sensations, a spider garret, and a peacock themed library (although Huysmans had apparently never met the man personally). (1)

Robert de Montesquiou and his cat

In other words, Huysmans’ eccentric protagonist wasn’t exactly one of a kind. During a time when making one’s own life into a work of art had become a veritable (anti?) social movement, his behavior was very much on trend.

It’s not hard to see, from these descriptions, why a penchant for purchasing pricey knick-knacks might place one at the precarious boundaries of psychological health in nineteenth-century France. In the 1890s, Husymans’ friend Edmond de Goncourt described this excessive collecting as bric-a-brac-o-mania (a term that Balzac had actually first used in the 1846 novella Le Cousin Pons). Goncourt noted that this passion now preoccupied “nearly an entire nation”—all those fellow troubled souls working against the “sadness of contemporary life and the uncertainty of tomorrow.” (2) Goncourt equated the pleasures of purchasing power with the best lovers; he embraced the “disease” as central to a decidedly modern artistic identity—one well-suited to this brave new era of immediate gratification.

Over a hundred years later, scholars of this time period are left not so much with the sadness of troubled souls but rather the intriguing remnants of early consumer culture. This new monthly column at Wonders & Marvels will be zooming in on some of those fascinating objects. We will explore how they inform research on the borders of nineteenth-century French literature, history, material, and visual cultures. As we examine various forms of archival bric-a-brac—from magazines to postcards to perfume bottles to books—we’ll look into the stories around them that drive innovative new research projects. We’ll also reflect on our scholarly penchants for collecting, and the modern tools that allow us to indulge our own bric-a-brac-o-mania, twenty-first-century style. Stay tuned!

1. For more about Robert de Montesquiou, as well as lots of juicy details about his home and those of many other writers, see Elizabeth Emery’s beautifully illustrated and highly informative study, Photojournalism and the Origins of the French Writer House Museum (1881-1914), published by Ashgate in 2012.

2. Edmond de Goncourt, La Maison d’un artiste. 2 vols. Paris: G. Charpentier, 1881.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York. You can hear her speak about her most recent book, Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman, on the New Books in French Studies podcast or see some of the fun images in this photo essay from Slate.com. She is also the author of The Hysteric’s Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle and serves as an Associate Editor of Nineteenth-Century French Studies.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York. You can hear her speak about her most recent book, Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman, on the New Books in French Studies podcast or see some of the fun images in this photo essay from Slate.com. She is also the author of The Hysteric’s Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle and serves as an Associate Editor of Nineteenth-Century French Studies.