Holly Tucker's Blog, page 32

May 14, 2015

Feeling Swinish: Or the Origins of “Pandemic”

By Holly Tucker (Editor-in Chief)

And here I thought that regular bathing in Purell would spare me from H1N1. A quixotic illusion, it turns out, for someone who teaches and has a grade-schooler. In the midst of mild fever, I started thinking about the origins of the term pandemic…

The seventeenth-century physician Gideon Harvey (no relation to William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of blood) first coined the term “pandemic” in 1666. Writing in the wake of the cataclysmic Great Plague of London, Harvey used “pandemic” to define “death’s direct door to most English.” He was not talking about the bubonic plague, which claimed over nearly 20% of London’s population in just a matter of months. Instead, it was consumption, or what we now call tuberculosis.

The seventeenth-century physician Gideon Harvey (no relation to William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of blood) first coined the term “pandemic” in 1666. Writing in the wake of the cataclysmic Great Plague of London, Harvey used “pandemic” to define “death’s direct door to most English.” He was not talking about the bubonic plague, which claimed over nearly 20% of London’s population in just a matter of months. Instead, it was consumption, or what we now call tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis may not seem as flashy or dramatic as other scourges like the plague, cholera, and smallpox, but it was no less deadly in the early-modern era. The disease, which scholars say peaked in urban centers sometime in the eighteenth century, cut a swath of destruction across much of Europe and the rest of the world, killing millions of people.

Harvey explained that diseases of remarkable “malignity and catching nature” should be called “a Pandemick, or Endemick, or rather a Vernacular Disease.” Pandemic comes from the Greek pan (all) and demos (people). And in one sentence, Harvey captured the complexity of widespread illness. It menaces the world (pandemic), its nations (endemic), and local communities (vernacular).

For Harvey, tuberculosis indeed stretched across the world. Yet as the title of his treatise makes clear, his world was surprisingly small. Morbus anglicus [English Death]: the world began in England, and ended in England.

Harvey was not alone in his insistence on nation-centered cartographies of disease. The sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries had the “French Pox” and the “English Sweate.” And more recently, influenza names have staked their own claim on the world map: the Russian Flu (1889-1890), the devastating Spanish Flu (1918-1919), the Asian Flu (1957-1958), and the Hong Kong Flu (1968).

Interestingly, since 2005, there has been an important shift in the naming of pandemic strains of illness. The Avian Flu and the Swine Flu are not just novel viruses; they have had historically novel names, breaking as they do from national monikers. But they, too, follow along borders—species borders, that is.

The term Swine Flu stresses the non-human origins of the virus. It reinforces an idealized notion that, like independent nation-states, there can be a firm distinction between animals and humans. But as the melting-pot of DNA in this viral strain shows, the distinction may just have been illusory to begin with.

[image error] [image error] [image error]

May 13, 2015

Behind the Book: The Witch of Painted Sorrows

By M.J. Rose (Guest Contributor)

I was six when I took my first art class. It was at the Metropolian Museum of Art in New York City. And I’ve never stopped studying or wanting to be painter. When I visit a city the first place I go to is the musuem. I am more at home looking at paintings and sculpture than doing anything, including reading. Of every subject I am always drawn first to art and artists.

When I was in Paris, I visited an exhibition of a late sixteen century female painter, Artemisia Gentileschi. She was a rarity and an anomaly. A woman artist who succeeded despite enduring so much. While there was no suggestion she dabbled in the occult, her resilience and determination inspired me to create a woman named, La Lune. A sixteenth century courtesan, the muse of a great artist who becomes a great artist herself.

While she isn’t the main character in The Witch of Painted Sorrows, she is at its heart. It’s her descendent, Sandrine, who three hundred years later, comes to Paris and has to overcome society’s rules and mores in order to live out her passions — as a woman and an artist during one of the most exciting times in Frances’ history.

Belle Epoch Paris was a melange of many different styles of art and poetry and philosophies. The old guard still ran the salons. Impressionsim battled for wall space with symbolism. Cults sprang up around occultism, spiritism and inspired artists and writers.

Belle Epoch Paris was a melange of many different styles of art and poetry and philosophies. The old guard still ran the salons. Impressionsim battled for wall space with symbolism. Cults sprang up around occultism, spiritism and inspired artists and writers.

All that diversity fascinated me. I spent a long time at the Gustav Moreau museum, looking not just at his masterpieces, but examining the hundreds of sketches hidden away. I searched out art nouveau buildings and visited museums to look at the work of the Nabis whose name itself which came from the Hebrew word for “prophet,” evoked both their mysticism and determination to develop a new artistic language.

M.J. Rose, NYT Bestseller (author of more than a dozen books) believes mystery and magic are all around us but we are too often too busy to notice… books that exaggerate mystery and magic draw attention to it and remind us to look for it and revel in it. Rose is a founding board member and co-president of International Thriller Writers and founder of AuthorBuzz.com

M.J. Rose, NYT Bestseller (author of more than a dozen books) believes mystery and magic are all around us but we are too often too busy to notice… books that exaggerate mystery and magic draw attention to it and remind us to look for it and revel in it. Rose is a founding board member and co-president of International Thriller Writers and founder of AuthorBuzz.com

May 12, 2015

Eliot Ness: Gangbuster Turned Union Buster

By Douglas Perry (Guest Contributor)

Early on the morning of July 26, 1937, dozens of steelworkers gathered at a union hall near the Corrigan-McKinney steelworks on Cleveland’s East Side. The men, on strike for two months, passed around cigarettes and black humor. They talked goals and strategy. Then they marched on the plant. By the time they came up on the complex’s massive gates, their numbers had grown into the hundreds – the largest strike demonstration yet in the city. Many of the strikers brought their wives or girlfriends. The women took up union songs, their strident sopranos cutting through the summer heat:

Comrades, slay me, for the coppers took my soul

Close my eyes, good comrades, for I played a traitor’s role.

The march had a triumphant, carnival atmosphere. Men waved placards and blew whistles. Women with children in their arms stood along the incline that overlooked the steel mill’s entrance. Watching the demonstration, they chanted slogans and bounced their babies.

As the strikers’ songs made clear, the union was wary of informers, but no one thought what had happened in Chicago on Memorial Day – ten union men shot dead by police – could happen here. Cleveland’s strikers had the public’s support. It seemed like the whole city had turned out on this beautiful morning to watch the demonstration. But then the women suddenly stopped chanting and shielded their children’s eyes. The crowd below them jerked, like drying laundry snapping in the wind. Men fell to their knees, some of them bellowing in pain. A phalanx of police officers had appeared, swinging clubs. Tear-gas guns popped. Eliot Ness, standing on the hillside with the young mothers, watched intently. He’d given the order.

Ness, the famed gangbuster, was also a union buster? When Ness posthumously became a pop-culture hero in the 1960s thanks to a network TV series about his Prohibition-era “Untouchables” squad, his controversial efforts to deal with labor strife in Cleveland fell out of his biography. After all, in the eyes of many participants, he was the bad guy in that tale.

Ness had become known across the country in the early 1930s for leading a special Prohibition Bureau squad – the Untouchables – against Al Capone’s Chicago mob. In 1935, four years after Capone was convicted of income-tax evasion, Ness arrived in Cleveland. It was the worst of the Great Depression, and the labor movement had become confrontational. After all, the world was falling apart, but a lot of the fat cats still seemed to be pretty fat. Unions, boosted by new federal laws that backed collective bargaining and other labor efforts, struck industries across the country.

They hit Cleveland’s steel companies hard. And management hit back just as hard, employing their own private armies to combat strike demonstrations. Ness was caught in the middle. Cleveland’s mayor, Harold Burton, was adamant that the city should remain neutral in labor conflicts, and Eliot believed that was the right call.

Inside the Labor Disputes

The labor dispute had started far from Cleveland. In March 1937, Pittsburgh-based U.S. Steel, the largest producer of steel in the world, did something unexpected, something revolutionary. It headed off a strike by signing a contract with the Committee for Industrial Organizations, guaranteeing workers a living wage and a forty-hour workweek. News of the deal quickly swept through Cleveland’s steelworkers’ community. Hundreds of men poured into their neighborhood bars to celebrate the new industry standard. They ended the night with a parade outside Republic Steel Corporation’s Corrigan-McKinney and Upson plants.

The celebrations were for nothing. Republic CEO Tom Girdler, the effective head of the collection of companies known as Little Steel, had no plans to follow Pittsburgh’s lead. “You can’t relax authority and hope to keep it,” he said. He declared he would never sign a contract with a union.

Inevitably, workers voted for a national strike against Little Steel, which was made up of Republic, Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, and Inland Steel Corporation. Violence came quickly and often, most notably the deadly Memorial Day bust-up of Republic picketers in Chicago, followed by the “Women’s Day Massacre” in Youngstown. Ohio Gov. Martin Davey called out the National Guard, which allowed the mills across the state to get up and running again with “scab” workers – and left strikers feeling more aggrieved than ever. When the Guardsmen left ten days later, Cleveland strike leaders declared that the city’s steelworks would not remain calm.

Cuyahoga County Sheriff Martin O’Donnell, a former Republic shift supervisor, deputized and armed a couple hundred Republic security officers for strike duty. Girdler effectively turned Corrigan-McKinney and Upson into armories, bringing in weapons and ammunition in huge trucks. Ness saw that a massacre worse than in Chicago was a very real possibility. He warned O’Donnell to keep his security officers in check, but he knew Republic wanted a fight and was going to find a way to get it.

The strikers, of course, wanted a fight, too. The women singing in front of Corrigan-McKinney’s big front gates on July 26 may have had peaceful intentions, but up on Dille Road, at the choke point leading to the mill’s entrance, not one of the men had a song in his heart. Strikers threw bricks and chunks of concrete at cars easing their way through. They pulled a man out of his car – a scab worker, they believed – and severely beat him. Seeing this, O’Donnell threw open the plant’s gates and sent his army into battle. More than a hundred company enforcers, wearing white armbands so they could identify one another, swarmed out of the mill with truncheons, pick handles and baseball bats. They arced through the crowd in a tight formation, battering everyone within reach.

That was when Eliot decided to take emergency measures. He had sympathy for the strikers. He believed their demands were fair. He knew that most of them had grown up in poverty and easily could have become criminals instead of working for a living. But none of that mattered right now. His crowd-management efforts simply weren’t working, and he had no other choice but to get tough. He sent the police into action.

Caught in the open between the Republic bruisers and a sudden wave of advancing police, the union men panicked. The company toughs cheered and shook hands as the strikers rushed out of the valley. The police told the enforcers to go back inside the gates and stay there.

Later in the day, Eliot reiterated to reporters that the city was staying neutral in the fight, that the police were just maintaining law and order. But as far as the strikers were concerned, Ness had sided with management and allowed scab workers to keep the mills running. That would prove to be a fatal blow to the strike, and the union blamed the safety director.

Ness enjoyed great success as Cleveland’s safety director: he reformed the corrupt police department, ran the mob out of town and made the roads less dangerous. But the Little Steel strike would dog Ness for the rest of his tenure in the working-class city. Public perceptions about the strike even contributed to his loss when he ran for mayor in 1947. It would take a popular network TV series after his death, a show that focused on his early career in Chicago, to make Clevelanders forget his role in the labor upheavals of the Depression years.

Douglas Perry is the author of The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the Beautiful Killers Who Inspired Chicago. Perry is an award-winning writer and editor whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, The San Jose Mercury News, The Oregonian, Tennis, and many other publications. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Douglas Perry is the author of The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the Beautiful Killers Who Inspired Chicago. Perry is an award-winning writer and editor whose work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, The San Jose Mercury News, The Oregonian, Tennis, and many other publications. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

May 11, 2015

Catch! Attacking Your Enemy with Words as well as Weapons

by Helen King

British Museum object reference 1851,0507.11

Twice in the last few days I’ve seen this picture of a lead sling-shot from the fourth century BC, found in Athens and in the collections of the British Museum (1851,0507.11). The first time the image was circulated on social media; I glanced at it but didn’t have time to think about it properly. The second time was at a conference on health in the ancient world, held at the University of Gothenburg, when one of the speakers, Professor Julie Laskaris, showed this same image as part of her keynote lecture on military medicine. The word on it is DEXAI, Greek for ‘Catch’!

I’m interested in what this suggests about literacy in ancient armies – the use of words on weapons could imply that the recipient is supposed to get the message, or at least that one’s fellow soldiers will be amused and encouraged by it before it is sent. Does it have some sort of power to make the slingshot more effective? Here, I think of Galen’s comments on amulets with words and/or images on them – namely, that the power resides in the material from which the amulet is made, not in what is written on it.

I went back to the social media reference to find out more. It turns out that a whole range of things could be written on slingshots. You could write the name of your general, or of a god. Or you could add something that would help your missile find its target: ‘Strike!’ or ‘Don’t miss!’ But other messages were far more jokey. One translates as ‘Here’s a sugar-plum for you!’

Thanks to the wonders of digitisation, we can all read the article in the Canadian Journal for 1864 in which the Revd John McCaul described the ancient inscribed slingshots that had been shown at various antiquarian societies’ meetings. Revd McCaul was a Church of Ireland minister who was then called to Canada as a college principal. A keen antiquarian himself with another publication on Romano-British inscriptions, he was not so keen as modern commentators are to discuss the inscriptions he calls ‘very coarse’. When Octavian’s army besieged Perugia in 40/41 AD, with Mark Antony’s wife and brother in the city, both sides wrote on the shot they used. One particularly choice example from Octavian’s army reads ‘Lucius Antonius the bald, and Fulvia, open up your ass’ (L[uci] A[ntoni] calve, Fulvia, culum pan[dite]). From the other side, one simply states ‘Seeking Octavian’s ass****’.

Coarse, indeed. But perhaps not unique to the ancient world. Bomb messages were used during the first Gulf War. My colleague Emma Bridges, whose current research project is on ancient military wives and is a former military wife herself, has seen pictures of bombs to be dropped by fighter jets during the second Gulf War carrying graffiti saying things like ‘Don’t bother using lube’. In Canada, Revd McCaul was known for ‘his skill at finding apt quotations from the Greek and Roman classics’. However, I suspect none of these quotations would have been taken from the world of the slingshot!

May 9, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Stranger Than Fiction

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

At Wonders & Marvels we pride ourselves on bringing you the untold, unusual, and unbelievable side of history. This week’s Cabinet of Curiosities is devoted to stories that prove that the truth is stranger than fiction.

What could be stranger than the afterlife of a poet’s hair? Yes, you read that right, a poet’s hair, or Edgar Allan Poe’s hair to be more precise. A Tennessee woman cleaning out her grandfather’s home discovered a lock of hair attached to a photograph which turned out to belong to the Father of the Detective Story himself. Not only was this Poe’s hair sample, it was a posthumous clipping taken after his death, but you will have to read the whole hairy tale for yourself.

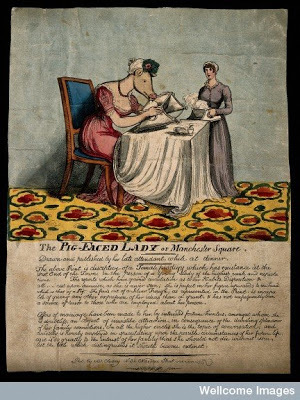

Imagine saying “One train ticket to the City of the Dead please!”. Well, in nineteenth-century London, you could have actually said those word, though your passenger would be traveling in a coffin rather than a first class seat. Opening on November 13, 1854, the London Necropolis Railway Station ferried over 200,000 bodies from London to the Brookwood Cemetery in order to help deal with overcrowded cemeteries in the city.

Imagine saying “One train ticket to the City of the Dead please!”. Well, in nineteenth-century London, you could have actually said those word, though your passenger would be traveling in a coffin rather than a first class seat. Opening on November 13, 1854, the London Necropolis Railway Station ferried over 200,000 bodies from London to the Brookwood Cemetery in order to help deal with overcrowded cemeteries in the city.

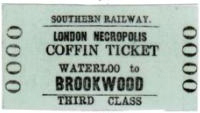

Experimental Medicine and the Ancient World

Most people have a healthy fear of undergoing surgery, even “routine procedures”. Now consider going under the knife without anesthesia…in the Ancient World. Just mentioning surgery in the Ancient World is enough to terrify this writer, but April Holloway’s article on Eight Impressive but Terrifying Cases of Ancient Surgery takes it to another level. Yet, some lucky patients even survived brain surgery in Siberia and others were willing to go under the knife for beauty’s sake. Even today’s rappers would be jealous of this bejeweled grill!

Most people have a healthy fear of undergoing surgery, even “routine procedures”. Now consider going under the knife without anesthesia…in the Ancient World. Just mentioning surgery in the Ancient World is enough to terrify this writer, but April Holloway’s article on Eight Impressive but Terrifying Cases of Ancient Surgery takes it to another level. Yet, some lucky patients even survived brain surgery in Siberia and others were willing to go under the knife for beauty’s sake. Even today’s rappers would be jealous of this bejeweled grill!

Fans of science fiction and fantasy, think Harry Potter, are used to all sorts of interesting medical cures, but even they might blink at some ideas of medieval medicine. Would you try rubbing the slime of a live snail on a burn? Or using the guts of a fat cat, the grease of a hedgehog, and the fat of a bear for a throat infection? Give me some lemon and honey please!

Rather than these cures, today we rely on tested and effective antibiotics, even for treating art. The famous frescoes of Pompeii were recently treated to kill bacteria living in the Dionysiac frieze. Turns out amoxicillin cures more than ear infections!

Like our name states, we are full of historical Wonders & Marvels, so for more eccentric stories, check out these recent articles:

Scythian Tatoos in Ancient Chinese Histories

The Fur Trapper Who Became an Accountant

Are you an avid reader? Then you will want to register for our monthly book giveaways!

May 8, 2015

The Royal Mommy Factor

By Rachel Mesch (Guest Contributor)

News sites from around the globe have been consumed this month with photos of the newest member of the British royal family—Princess Charlotte Elizabeth Diana, daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. It’s perhaps not surprising that images of the proud parents beaming over their baby’s puckered new face are nearly identical to the on es that circled the internet when Charlotte’s big brother George was born two years ago—but what about their striking similarity to images that consumed an international public over a hundred years ago?

Empress Eugenie with her son in 1862

In fact, royals were among the first celebrities in the nineteenth century, and this was especially so in France, where photography and mass culture interacted early and often in what was a highly productive (and profitable) synergy. By the turn of the century, you could collect images of your favorite international icons through postcards, posters, or the shiny new photographic magazines that were flying out of Parisian kiosks and into the homes of hungry readers by the thousands. In addition to performers like Sarah Bernhardt and Cléo de Mérode, favorite early celebs included the exotic Spanish-born Empress Eugénie (the wife of Napoleon III), who was often pictured with her beloved only son, and the lovely long-haired Empress Elisabeth of Austria.

The rapid and widespread circulation of celebrity images, and the narrative arc that these early magazines now supplied around them, created a new sense of intimacy with the happy few, inviting readers into their homes, and into the illusion of sharing, in some small way, in their lives. As a result, after admiring these dazzling figures, as one early French women’s magazine described, you might return temporarily comforted to your own more modest existence.

Royal motherhood played a special role in the psychological process that fed the burgeoning of celebrity culture: seeing monarchs engaged in intimate family moments brought readers closer to an alluring world they could never hope to inhabit, while mitigating that potentially alienating distance through the shared experience of motherhood. That we know the feel of a baby in our own arms helps us to forget how far we are in truth from a certain princess’s fame and fortune. This is what Richard Shickel calls “intimate strangers” in his history of celebrity in the US, but the phenomenon goes farther and deeper than mid-twentieth century America.

A story from the September 1907 issue of La Vie Heureuse (literally, the happy life), a precursor to Vogue, Elle and People all rolled up in one, assembles royal babies from across a tumultuous globe—Spain, England, Norway, and Russia—and notes how much they have in common when domesticity is on display rather than foreign policy. Next to their babies, writes the author, and far from politics, “queens are only young women, watching tenderly over those frail, sacred heads.” Members of the royal court are just mothers, who admire their little ones “like the most simple of their subjects.”

A story from the September 1907 issue of La Vie Heureuse (literally, the happy life), a precursor to Vogue, Elle and People all rolled up in one, assembles royal babies from across a tumultuous globe—Spain, England, Norway, and Russia—and notes how much they have in common when domesticity is on display rather than foreign policy. Next to their babies, writes the author, and far from politics, “queens are only young women, watching tenderly over those frail, sacred heads.” Members of the royal court are just mothers, who admire their little ones “like the most simple of their subjects.”

So why are we still unable to tear our eyes away from those pictures of the impeccable Kate Middleton with her darling new addition, just as Belle Epoque readers devoured images of baby czars and their mothers? Perhaps because they allow us to momentarily forget the less-than-glamorous aspects of motherhood, and to believe that the Duchess of Cambridge, in her generic human way, is someone we might resemble: the royal mommy celebrity as our best self.

Rachel Mesch is the author of Having it All in the Belle Epoque: How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman and The Hysteric’s Revenge: French Women Writers at the Fin de Siècle. She serves as an associate editor of Nineteenth-Century French Studies and teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York.

May 7, 2015

Ruff-ing It and the Politics of Fashion

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (Former W&M Regular Contributor)

Writing in 1637, the Marquis of Careaga deplored the “delicate and womanly” fashions that enraptured Spanish men. He warned that these indulgences “overthrew their spirits, unnerved their determination, weakened their energy, and diminished their manly vigor.”

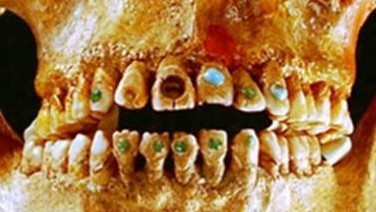

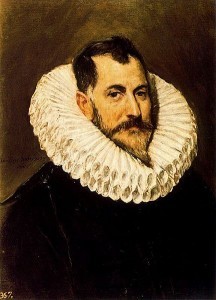

We might wonder what sort of fashions could inspire such vitriol. A particular item stood at the heart of his comments and those of other moralists: a ruff. Specifically, a Spanish variation on the ruff known as the cuello. The cuello, represented here in a portrait by El Greco, had become an object of excess. This collar was several inches high, tinted with powders, and often decorated with fancy threads. And it had to be washed and starched daily to maintain its appearance. By the early seventeenth century, some tried to elevate their cuellos even further, using an undergirding support known as an alçacuello. Thus, the cuello came to embody a host of moralizing complaints that ranged from foreign policy to the economy to fears of compromised masculinity.

We might wonder what sort of fashions could inspire such vitriol. A particular item stood at the heart of his comments and those of other moralists: a ruff. Specifically, a Spanish variation on the ruff known as the cuello. The cuello, represented here in a portrait by El Greco, had become an object of excess. This collar was several inches high, tinted with powders, and often decorated with fancy threads. And it had to be washed and starched daily to maintain its appearance. By the early seventeenth century, some tried to elevate their cuellos even further, using an undergirding support known as an alçacuello. Thus, the cuello came to embody a host of moralizing complaints that ranged from foreign policy to the economy to fears of compromised masculinity.

To begin with, the dyes used to tint them were imported from Spain’s enemy, the Dutch. Many argued that the nobility’s ducados would benefit Spain more if they were spent locally. Finally, the cuello violated the prevailing code of virtuous virility that prized moderation, control, and a sense of effortlessness in matters of style. If anything, the cuello screamed excess and effort. Everyone knew how labor-intensive their care and presentation was. Men who indulged in this fashion were often characterized as effeminate. Their inability to dress with moderation compromised their masculinity. At a time when Spain was engaged in military conflict across the globe, the “manly vigor” of its male citizens had serious political consequences.

The crown, in fact, vigorously legislated against them. As early as 1594 it forbid the adornment of cuellos, specified a particular width for them, and that any decorative elements be white. Again, in 1600 it issued orders regarding the width of cuellos. Yet the fashion endured. Ultimately, rather than modify their appearance, the crown abolished them completely in 1623. It presented as an alternative the low, flat collar of the valona. Even the king himself was not above this new rule as we can see here in Velázquez’ portrait of Philip IV (1621-1665). Not unlike today, seventeenth-century fashion was intensely political.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in April 2012.

May 6, 2015

The Civilian Toll of the Lusitania

By Diana Preston (Guest Contributor)

At 2.10 pm on 7 May 1915 off the southern Irish coast the German submarine U-20 fired a single torpedo at the British Cunard liner RMS ‘Lusitania’. Eighteen minutes later the 30,000 ton vessel slid beneath the waves with as one survivor recalled ‘a long, lingering moan’. Among the  1198 killed were 128 citizens of the still neutral United States. Their deaths in an attack illegal under international maritime law and which the ‘New York Nation’ condemned as ‘a deed for which a Hun would blush and a Barbary pirate apologise’ soured already strained relations between the German and the United States governments and fueled bitter diplomatic exchanges about the German campaign of attacking merchant shipping without warning. In April 1917 these culminated in the United States’ declaration of war.

1198 killed were 128 citizens of the still neutral United States. Their deaths in an attack illegal under international maritime law and which the ‘New York Nation’ condemned as ‘a deed for which a Hun would blush and a Barbary pirate apologise’ soured already strained relations between the German and the United States governments and fueled bitter diplomatic exchanges about the German campaign of attacking merchant shipping without warning. In April 1917 these culminated in the United States’ declaration of war.

The bigger geopolitical story with its background of intrigue, spying and code breaking and – after the sinking – cover-up of the true facts by both the British and German governments fascinated me. However, it was small details in my research which helped me understand just a little of the human tragedy of the victims and their families. Among such poignant detail was a notice placed by an anxious mother in the window of a house in Cobh where survivors were landed:

‘Missing, a baby girl, 15 months old. Very fair curly hair and rosy complexion. In white woollen jersey and white woollen leggings. Tries to walk and talk. Name Betty Bretherton. Please send any information to Miss Browne, Queen’s House.’

Track of Lusitania by William Lionel Wyllie

Wading into the sea near Cobh at the same time of year as the sinking, I found the water at 2oF very cold. Within five minutes I was shivering, within ten feeling numb and within fifteen back on the beach thinking about the traumatized people shivering in the water for three hours, clinging to wreckage.

Tipping buttons and small pieces of clothing cut from the garments of unidentified victims from dusty boxes in the Cunard archives in Liverpool and reading letters in the same boxes from passengers’ families seeking information and describing birthmarks, moles and scars to aid identification truly moved me, bringing home that these were real people just like myself.

What a large part luck (bad) can play in a disaster also struck me. If the morning of 7 May 1915 hadn’t been foggy, the ‘Lusitania’ would have been past Cobh and out of danger by early afternoon. If her captain hadn’t decided to take a four point bearing to fix her position accurately she wouldn’t have been travelling slowly in a straight line when attacked.

Also, the run time of the torpedo – with the diameter of a steering wheel and longer and heavier than an automobile – was only thirty-five seconds. Given the Lusitania’s speed, if the missile had been fired just five seconds earlier or twenty seconds later it would have missed entirely and the liner would have sailed serenely on. Instead it struck one of her most vulnerable points, near a major bulkhead, ripping a hole in the longitudinal starboard bunker. Arcing helplessly out of control and continuing to make way, the ‘Lusitania’ ploughed into the sea.

All these details impressed upon me the abiding significance of the simple Gaelic inscription on the monument to the disaster in Cobh: ‘Peace in God’s name.’

Diana Preston is an acclaimed historian and the author of A Higher Form of Killing, Before the Fallout: From Marie Curie to Hiroshima (winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for History), The Boxer Rebellion, and The Dark Defile: Britain’s Catastrophic Invasion of Afghanistan, 1838-1842, among other works of narrative history.

Diana Preston is an acclaimed historian and the author of A Higher Form of Killing, Before the Fallout: From Marie Curie to Hiroshima (winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for History), The Boxer Rebellion, and The Dark Defile: Britain’s Catastrophic Invasion of Afghanistan, 1838-1842, among other works of narrative history.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on May 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

May Book Giveaways

Jonathan Schneer, “Ministers at War: Churchill and His War Cabinet”

Henry Hemming, “The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy”

Helen Castor, “Joan of Arc: A History”

Diana Preston, “Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy”

May 5, 2015

The Ingenious Mr. Pyke

By Henry Hemming (Guest Contributor)

There’s a moment towards the end of an otherwise heavy-going military conference in Quebec, in August 1943, when a senior Allied commander pulled out a pistol in a room containing some of the most powerful men on earth, took careful aim and pulled the trigger. Stranger still was what he had in his sights. It was a block of ice – at least that’s what it appeared to be.

Mountbatten

The man with the pistol was Lord Louis Mountbatten, grandson of Queen Victoria and Commander of Combined Operations. He’d just fired at a block of ‘Pykrete’, a revolutionary material made out of nothing more than water and sawdust mixed together before being frozen. Its name came from its inventor, Geoffrey Pyke, and concrete, for this unusual icy compound had the tensile strength of reinforced concrete.

Mountbatten had fired at the Pykrete and to the astonishment of his audience his target did not disintegrate in a hail of icy splinters. Instead it stood firm. More worrying, however, was that the bullet ricocheted off in the direction of the man who had fired the gun. Accounts of what happened next vary.

Winston Churchill, seated in the front row, saw the bullet fly past him and miss Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal by a matter of inches. In another account the bullet nicked Fleet Admiral King, Commander-in-Chief of the US Fleet; one man thought it landed in Mountbatten’s stomach; another remembered it taking a lump out of the wall. Towards the back of the room General Sir Leslie Hollis was seen to dive under the nearest table where he ‘collided, skull to skull, with [Field Marshal] Alan Brooke, approaching from the opposite direction’.

Geoffrey Pyke

Even if we can’t be sure where that bullet landed, this episode clearly woke everyone up and prepared them perhaps for the radical use to which Pykrete was to be put.

At this point I’m going to come over all coy. Rather than reveal what that use was I’ll leave it for my account of Pyke’s life. Suffice to say that it was another radical idea from one of the great innovators of the 20th century, a little-known Englishman called Geoffrey Pyke whose genius lay not so much in a single invention but the dizzying range of his ideas. To name a few, he invented a pre-school inspired by Freudian psychoanalysis, escaped from a German concentration camp, made a fortune on the metals market and towards the end of his life he pioneered the maverick military unit seen today as the precursor to the US and Canadian Special Forces.

Yet for me his most radical idea can be found in his response to those who called him a genius. He rejected this label, saying instead that he had an intellectual technique. It could be learned by anyone. It could be applied to anything. It was reading this which finally convinced me to write Pyke’s biography, if for no other reason than to bring to life this man’s extraordinary approach to the world.

Henry Hemming is the author of five works of non-fiction and among others has written for The Sunday Times, The Economist and The Washington Post. He lives in London with his wife and daughter.

Henry Hemming is the author of five works of non-fiction and among others has written for The Sunday Times, The Economist and The Washington Post. He lives in London with his wife and daughter.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of The Ingenious Mr. Pyke in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on May 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

May Book Giveaways

Jonathan Schneer, “Ministers at War: Churchill and His War Cabinet”

Henry Hemming, “The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy”

Helen Castor, “Joan of Arc: A History”

Diana Preston, “Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy”

May 4, 2015

Scythian Tattoos in Ancient Chinese Histories

By Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

Archaeologists have found artistic representations in archaeological sites of the Shang to Han Dynasty periods (1500 BC to AD 220) reflecting tattooing practices. It is interesting that the earliest Chinese word for writing, wén, referred to tattoos. Evidence of tattooing customs among the nomadic steppe cultures of Central Asia–known to the ancient Greeks as Scythia–also appears in many Chinese chronicles.

Several Chinese sources described tattoos as common body adornments among the “barbarian” nomads of the Northern and Western Wilderness, beyond the imperial borders of China. For example, in the Warring States and early Han period (about 475 BC to 87 BC), the Liji (“Record of Rites,”) reported on the “wild” tribes of mounted archers of Inner Asia: they ate meat, wore animal skins, and tattooed their foreheads. In the third to first centuries BC, the Zhan Guo Ce (“Intrigues of the Warring States”), stated that the Western horse-archers engraved their left shoulders with tattoos. The Nan Shih (“History of the Southern Dynasties”) of AD 630 refers to the steppes as the “Land of the Tattooed.” These “uncivilized” people marked themselves “with stripes and spots like wild beasts.” It also noted that Siberian peoples of “gigantic” stature wore tattoos that signified their courage and signaled their marital status.

The powerful confederation of nomad tribes of the West became known to the Chinese as Xiongnu. A Han history by Sima Qian (Shiji, “Records of the Historian,” 147-85 BC) recounts the emperor’s negotiations with the aggressive Xiongnu who exerted continuous pressure on China’s Western frontier. The nomads held the upper hand in the fifth to third centuries BC. To mollify them, Chinese rulers sent lavish tributes and Han princesses as wives to seal treaties. When Chinese ambassadors arrived with gifts, however, the nomad leaders demanded that the envoys be tattooed (me [mo] ch’ing, “to tattoo with black ink”) before they could meet the Shan-yu (“The Greatest,” chieftain).

The Chinese, like the ancient Greeks and Romans, considered tattooing a form of punishment, the mark of a slave or criminal. Even so, ancient Greek vase painters portrayed beautiful barbarian women decorated with tattoos. Permanent body markings evoked ambivalence. Likewise, the lines between tattoos that were shameful marks, heroic badges of honor, and beautiful decorations began to blur for the Chinese as their dealings with steppe nomads increased and some of steppe customs–such as riding warhorses and wearing trousers–began to influence Chinese culture. Acceptance of tattoos became more common, especially among Chinese travelers, traders, explorers, and envoys who interacted and lived among the nomads. “The Mission to the West” in the Han Shu by Zhang Qian (Chang K’ien), records that some Chinese envoys, for example Wang Wu, who was himself a northerner familiar with Xiongnu customs, readily agreed to receive tattoos in order to meet with nomad leaders.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).