Holly Tucker's Blog, page 33

May 2, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: The Animal Kingdom

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Generally on Wonders & Marvels, we chat about human history. Today we are going to look at the tale of our furry, and not so furry, friends (pun intended) . Since the dawn of time the game of predator and prey between men and animals has evolved, to the point where we consider some animals as mankind’s best friend. This week we will look at history of some remarkable animals, from extinct to domesticated.

Don’t Go the Way of the Dodo

We all now the story of the dodo bird, the strangely billed avian hunted to extinction by European explorers in the 17th century. However, you probably didn’t know that the Dodo bird almost went extinct 4,000 years earlier. What threat did the famous flock face? It’s own poop! Scientists researching the ancient lake, and fossil treasure trove, of Mare aux Songes in Mauritius have discovered that the feces mixed with the wetlands to create a deadly cocktail that almost killed off the Dodo amongst other animals.

That got us thinking about other species that “went the way of the Dodo”and what led to their extinction. Consider the great Wooly Mammoth, why didn’t it survive like it’s relative the elephant? Luckily for the W&M readers, scientists are closer to finding these answers. Recently scientists have examined the DNA of the Wooly Mammoth to find that genetic diversity amongst the population led to the animals decline, even before the end of the Ice Age.

That got us thinking about other species that “went the way of the Dodo”and what led to their extinction. Consider the great Wooly Mammoth, why didn’t it survive like it’s relative the elephant? Luckily for the W&M readers, scientists are closer to finding these answers. Recently scientists have examined the DNA of the Wooly Mammoth to find that genetic diversity amongst the population led to the animals decline, even before the end of the Ice Age.

From Man’s Best Friend, to Man’s Hero

Font-de-Gaume, France Cave Painting

If extinct species aren’t your thing, maybe you are more interested in the mammal sitting right next to you on the couch. The debate of cats vs. dogs may never be resolved, but it is a fact that the dog was the first animal that humans domesticated. So even if you don’t consider the canine man’s best friend, we could call him man’s oldest friend. Yet, until recently studies disagreed about exactly where and when dog domestication first occurred. Now an unprecedented cooperation between archaeologists and scientists is working together to solve this mystery. Read more about it in the recent issue of Science.

The domesticated dog is more than man’s oldest friend, these canine companions have often been man’s protector. A new exhibit at the Bishopsgate Institute celebrates the heroism of dogs in World War I. This collection, possibly the largest photo collection of dogs in the world, explores the role of dogs both as companions, workers, and heros from 1914-1918.

Flinders and Trinn

Don’t worry cat lovers, at W&M we are equal opportunity animal lovers. So is the Museum of Maritime Pets that is devoted to stories of the story of dogs and cats at sea. This online museum chronicles both the adorable and heroic seafaring companions. For example, it includes the tribute to 18th and 19th century explorer by Matthew Flinders for his cat Trinn, the first man-cat team to circumnavigate Australia. Read all about the museum at the Smithsonian’s website or visit the museum yourself: it’s only a click away!

If you are anxious to learn more about animal history, check out these recent stories:

No Scrubs: Breeding a Better Bull

Like books? Take advantage of our monthly book giveaways!

April 30, 2015

The First Baseball Speed Gun

By Joseph Wallace (Guest Contributor)

How fast does a baseball travel after being thrown by a major-league pitcher? A remarkable article in the December, 1912, issue of Baseball Magazine showed that the first accurate measurements were made decades before the invention of the modern-day radar gun.

How fast does a baseball travel after being thrown by a major-league pitcher? A remarkable article in the December, 1912, issue of Baseball Magazine showed that the first accurate measurements were made decades before the invention of the modern-day radar gun.

Titled “One Hundred and Twenty-two Feet a Second!”, the piece sought to measure the speed of the pitches thrown by future Hall of Famer Walter Johnson, widely considered the hardest thrower of his era. To do so, the magazine’s editors turned to unlikely source: the Remington Arms Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Remington had recently designed an elegant electrical apparatus to measure the speed of the bullets fired from their rifles. Baseball Magazine realized that the same device could measure hurled baseballs just as well.

In the experiment, Johnson was enlisted to throw a baseball through a delicate wire mesh suspended in a wooden frame. After brushing through the mesh, the ball would strike a sturdy steel plate bolted to the wall beyond.

Attached to both the wires and the steel plate was the apparatus, which measured the two impacts and the time elapsed between them. Knowing the distance between the mesh and plate allowed the editors to determine the speed of Johnson’s throw.

Walter Johnson’s fastest measured traveled 122 feet per second – or, as we measure pitches today, 83 miles per hour. As the awestruck editors hastened to point out, this was far faster than the speedy Twentieth Century Limited railroad train traveling at a mile a minute…and fully half the speed of one of Remington’s deadly bullets.

Important addendum: As baseball fans know, most pitchers today can throw a baseball more than 90 miles per hour. The reason Johnson’s pitches were so much slower? It took him many tries before he finally guided the ball through the small mesh framework, by which time he was far more concerned with accuracy than speed!

This speed machine – and the Baseball Magazine article – play important roles in Diamond Ruby. During the section of the novel when Ruby is working on Coney Island (in a sideshow challenging men to “outthrow the girl pitcher”), it is Remington’s electrical apparatus that allows pitching speeds to be compared….and the real-life article that tells Ruby and her girls that such a device exists.

Joseph Wallace has been a writer of popular history for more than twenty years, covering subjects ranging from science and natural history (A Gathering of Wonders: Behind the Scenes at the American Museum of Natural History) to baseball (The Autobiography of Baseball). His first novel, Diamond Ruby, set in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and inspired by a photograph he found at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library, was published in May by Touchstone. He is currently at work on a sequel.

Joseph Wallace has been a writer of popular history for more than twenty years, covering subjects ranging from science and natural history (A Gathering of Wonders: Behind the Scenes at the American Museum of Natural History) to baseball (The Autobiography of Baseball). His first novel, Diamond Ruby, set in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and inspired by a photograph he found at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library, was published in May by Touchstone. He is currently at work on a sequel.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in January 2011.

April 28, 2015

Stafford Cripps: The Man Who Challenged Churchill

By Jonathan Schneer (Guest Contributor)

In May 1940 the Nazis rolled like thunder through Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg and France. No one could stop them. In Britain the appeaser Neville Chamberlain stepped down as Prime Minister, and the pugnacious Winston Churchill stepped up. He knew he must form an all-party coalition to confront the emergency, and so brought into his government Labour Party socialists, Liberals, fellow Conservatives, representatives of two smaller parties that no longer exist, and even men who belonged to no political party at all. He called his team “the Grand Coalition.”

“The Grand Coalition” constituted as high-powered, ambitious and determined a group of hard men as has ever governed Britain. Yet even as they fought the common foe, they argued amongst themselves and maneuvered against each other – and against their leader. Eighty years after Abraham Lincoln did it, Winston Churchill had assembled his own “team of rivals.”

“The Grand Coalition” constituted as high-powered, ambitious and determined a group of hard men as has ever governed Britain. Yet even as they fought the common foe, they argued amongst themselves and maneuvered against each other – and against their leader. Eighty years after Abraham Lincoln did it, Winston Churchill had assembled his own “team of rivals.”

One member of the team believed he could lead better than Winston Churchill. This was Stafford Cripps, whom the Labour Party expelled in 1939 for advocating cooperation with Communists in a popular front against fascism. Cripps was a patriot, a militant socialist, a militant Christian, a vegetarian, a teetotaler. Really he was a charismatic Puritan, with extraordinary capacity for work and organization. Churchill appointed him ambassador to Russia in June 1940. Cripps wanted to play a larger role – at home. He returned in January 1942. Churchill still wanted to take advantage of his great abilities, but understood that Cripps saw himself as an alternative Prime Minister. How Winston Churchill dealt with Stafford Cripps provides insight into how he kept his own “team of rivals” working together in a war that Britain had to win.

The first move was to partially fulfil Cripps’s ambitions by bringing him into the War Cabinet as Leader of the House of Commons. The role of the Leader is to interpret Government policy to House Members, and House opinion to the Government. Cripps was unsuited for the job both temperamentally and politically, as Churchill knew. Cripps never went to the House bar because he did not drink. He was man without a party, and so had no claque of supporters among Labour Members, his natural constituency in the House. He had stepped into a trap.

In Cripps’s first speech to the House he characteristically condemned dog racing, horse racing, boxing matches and personal extravagance, unwittingly insulting members of all parties at once. A whispering campaign against him commenced. Soon afterwards, Cripps noticed Members leaving for lunch while the Prime Minister was speaking. He chastised the House: “I do not think that we can conduct our proceedings here with the dignity and the weight with which we should conduct them unless Members are prepared to pay greater attention to their duties.” Everybody condemned him again.

Deeply crestfallen Cripps offered his resignation. Churchill accepted it and appointed him Minister of Aircraft Production, where he had wanted Cripps in the first place, but which Cripps had thought beneath his dignity. Cripps had a seat in the Cabinet but not in the smaller, more exclusive and more powerful War Cabinet. He would finish out the war there, making a useful contribution, but never again appearing as a rival to the Prime Minister.

Winston Churchill is rarely portrayed as a shrewd manager of men, but in fact as I discovered when researching my book, he was a master manager of men. Churchill’s “team of rivals” was deeply riven by conflicting personal ambitions, ideologies, and personalities, as the episode with Stafford Cripps reveals, but the Prime Minister held the group together until the war was won.

Jonathan Schneer teaches Modern British History at Georgia Tech. He is the author of seven books including London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis, The Thames: England’s River, and The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, which won a National Jewish Book Award in 2010. He lives in Decatur GA.

Jonathan Schneer teaches Modern British History at Georgia Tech. He is the author of seven books including London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis, The Thames: England’s River, and The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, which won a National Jewish Book Award in 2010. He lives in Decatur GA.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Ministers at War in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on May 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

May Book Giveaways

Jonathan Schneer, “Ministers at War: Churchill and His War Cabinet”

Henry Hemming, “The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy”

Helen Castor, “Joan of Arc: A History”

Diana Preston, “Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy”

April 27, 2015

Who Was The Most Successful Pirate in History

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

[image error]

Any guesses? Edward Teach, commonly known as Blackbeard? Captain Kidd? Captain Morgan? Grace O Malley, aka the Pirate Queen? Sir Francis Drake?

None of them are even close, though Drake has the distinction of capturing what may well have been the largest prize taken in a single raid: the Spanish galleon Cagafuego. The title goes to Cheng I Sao (aka Hsi Kai Ching, Ching Shih, Lady Ching, or Mrs. Ching depending on the vintage and quality of the account you read.), who terrorized the South China Seas in the first half of the nineteenth century–a time when many Chinese women were literally hobbled by bound feet.

Piracy was a family business in nineteenth century China. Pirate clans lived on their boats–some of them lived their entire lives without setting foot on land. Within the world of the pirates. some women held rank, commanded ships, and fought shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts. Cheng I Sao took female participation in the family business to a new level.

According to popular accounts, Cheng I Sao was a Canton prostitute who married the successful pirate Cheng I in 1801 and soon became his partner in building a successful confederation of pirates from competing clans. When Cheng I died in 1807, his widow took over. She avoided succession struggles by appointing her adopted stepson as her second in command and later marrying him.

At the height of her success, Cheng I Sao controlled 1500 ships and more than 70,000 men, organized in six fleets, each with its own flag and commander. (Talk about a pirate queen!) Her fleets attacked ships of all kinds, from small traders to imperial war ships, and ran a protection racket along the coast.

By 1809, Cheng I Sao was powerful enough to threaten the port city Canton (now Guangzhou). The Chinese government turned to the European powers for help, leasing the 20-gun ship HMS Mercury and six Portuguese men-of-war. Big guns were not enough to defeat the pirate admiral’s fleet. In 1810, the Chinese changed tactics and offered the pirates amnesty.

Cheng I Sao decided it was in her best interests to negotiate peace terms with the Chinese empire. She proved to be as effective at the bargaining table as she was on the deck of a ship: the Chines granted her pirates universal amnesty, the right to keep the wealth they had accumulate, and jobs in China’s military bureaucracy. Cheng I Sao retired in Canton, where she reportedly lived a peaceful life until her death at 69 “so far as was consistent with the keeping of an infamous gambling house.” (What? You expected her to take up knitting and mahjong?)

April 26, 2015

How I Write History…with Heather Webb

An Interview with Heather Webb (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: When did you know you wanted to be a writer? How did you decide on historical fiction?

Wonders & Marvels: When did you know you wanted to be a writer? How did you decide on historical fiction?

Heather Webb: I’ve carried books around with me since I was five years old. I journaled most days by age eight, and dabbled in a short story or two by age thirteen. I won a few essay contests in high school and was copy editor of my college newspaper and yet, I still never considered being a writer. It didn’t seem like a plausible thing to do—few jobs, little money, no guarantees. So I worked toward a degree in French. Now there’s a great career move! I adored it, but there’s not exactly a ton of money and stability in French either. High school teaching was a blast though, and I still miss the kids. They made me laugh every day.

It wasn’t until I gave up teaching to raise children that I realized how much I truly adored books—reading them, critiquing them, and finally, writing them. The first days I put the proverbial pen to paper, I felt as if I had stepped into a new, yet strangely familiar skin. As if it had been waiting for me all along. Writing had always been a part of my identity though I wasn’t conscious of it. I’ll never ignore that little voice again.

As for writing a historical novel, it chose me. After years of teaching high school, I was very drawn to young adult fiction, and I even started a novel, but quickly abandoned it. Josephine Bonaparte came to me in a dream (my first novel’s subject) and her voice pestered me weekly. I couldn’t let her go. Now I’m hooked. I’ve always been a bit of a history buff anyway.

W&M: Your newest novel, Rodin’s Lover, is based on the life of French artist Camille Claudel. How do you use historical sources to enrich your writing?

Heather Webb: Travel, artifacts, letters, biographies, cultural and political studies, linguistics, foods—these are all aspects of an era I delve into to enrich the base of my novels.

For Rodin’s Lover, I studied the artists’ pieces visually and read about the inspiration behind them before I began writing. Once I had plotted the novel, I looked for ways to emphasize themes in the book with individual works. It was a bit like fitting pieces of a puzzle together.

Heather’s sitting and standing desks she uses alternately.

W&M: What is the most challenging part about writing a fictional tale based on a real historical figure?

Heather Webb: Balancing a historical figure’s negative traits with those that are sympathetic. There are times you really don’t like something about a person/character, but in order to accurately portray them, you have to “go there”. In both of my novels I faced this challenge. Yet, don’t we also love a fallible character? What is so endearing to us as readers is the character’s struggle to be better, not necessarily their perfections.

W&M: What advice do you have for writers who are writing fiction for the first time?

Heather Webb: Read as often as possible with a studious eye, especially in your genre, but also widely. It’s the single most helpful tool a writer can use to expand their understanding of fiction. Respect and trust your process. You may write quickly or slowly—this doesn’t matter. What matters is practice and growth. And finally, take the time to connect with other writers. They can not only become part of your support network, they become critique partners and guides in an ever-shifting and difficult industry.

April 25, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Let’s Talk Fashion!

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Let’s talk fashion! Something as seemingly frivolous as what a person wears or how they style their hair actually tells us a lot about a culture. What we think of as self-expression today, has traditionally been a highly charged form of cultural, religious, and even political expression. This week articles take a look at style from ancient shopping habits to today.

For United States teenagers, April means one thing: prom. You are probably picturing ladies decked out in sequins, puffy sleeves, and ball gowns, but what about a lady in a tux? Unconventional? Sure, but not that shocking in 2015. Think again. A woman in a tux still stirs up controversy at your local high school; yet, daring dames have been wearing tuxes for over 100 years. SheWired takes a look at the history of women who wore tuxes whether society approved or not.

Imagine the hero of a historical novel: strong, handsome, intelligent…and decked out in lace and high heels. These days, lace and high heels are staples of women’s fashion; but, historically men were just as likely to be seen sporting these classic style statements. The English History Authors Blog recently took a look at how costume affects characters in historical fiction. Spoiler alert: men couldn’t walk in high heels either!

Owls and Jowls

Have you ever considered Iron Age fashions? Me neither. However, a recent find on a Danish Island has us pondering Iron Age style. A stunning bronze brooch in the shape of an owl, complete with enamel accents dated to 100-250 AD was found in a settlement. It turns out that this accessory, while a sign of prestige, was part of a trend of nature inspired clasps during the period.

Fu manchu. Goatee. Soul patch. Muttonchops. Men’s facial hair has a wide variety of colorful names to describe its many variations. But, did you ever consider the simple sideburn? It may be a less provocative name than some of the recent monikers, yet, it has a fun history. Find out the tale behind this now commonplace term here.

Retail Therapy in Ancient Rome

Of course, no discussion of fashion would be complete with out a little history on shopping. Where better to start than the cosmopolitan epicenter of the Ancient World: Rome. Poet Martial once said Rome resembled one big shop with the sellers of all sorts of wares lining the streets. To get all the details on Rome’s shopping habits, and the ones that we still follow, read Claire Holleran’s Handbook to shopping in Rome.

Want to know more about the history of fashion and style? Check out some of our recents posts:

When Agnodice Became a Handbag

Unhairing in the 1800s: Animal Processing and Personal Care

Love to read? There are still a few days to sign up for our book giveaways!

Cabinet of Curiosities: xix

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Let’s talk fashion! Something as seemingly frivolous as what a person wears or how they style their hair actually tells us a lot about a culture. What we think of as self-expression today, has traditionally been a highly charged form of cultural, religious, and even political expression. This week articles take a look at style from ancient shopping habits to today.

For United States teenagers, April means one thing: prom. You are probably picturing ladies decked out in sequins, puffy sleeves, and ball gowns, but what about a lady in a tux? Unconventional? Sure, but not that shocking in 2015. Think again. A woman in a tux still stirs up controversy at your local high school; yet, daring dames have been wearing tuxes for over 100 years. SheWired takes a look at the history of women who wore tuxes whether society approved or not.

Imagine the hero of a historical novel: strong, handsome, intelligent…and decked out in lace and high heels. These days, lace and high heels are staples of women’s fashion; but, historically men were just as likely to be seen sporting these classic style statements. The English History Authors Blog recently took a look at how costume affects characters in historical fiction. Spoiler alert: men couldn’t walk in high heels either!

Owls and Jowls

Have you ever considered Iron Age fashions? Me neither. However, a recent find on a Danish Island has us pondering Iron Age style. A stunning bronze brooch in the shape of an owl, complete with enamel accents dated to 100-250 AD was found in a settlement. It turns out that this accessory, while a sign of prestige, was part of a trend of nature inspired clasps during the period.

Fu manchu. Goatee. Soul patch. Muttonchops. Men’s facial hair has a wide variety of colorful names to describe its many variations. But, did you ever consider the simple sideburn? It may be a less provocative name than some of the recent monikers, yet, it has a fun history. Find out the tale behind this now commonplace term here.

Retail Therapy in Ancient Rome

Of course, no discussion of fashion would be complete with out a little history on shopping. Where better to start than the cosmopolitan epicenter of the Ancient World: Rome. Poet Martial once said Rome resembled one big shop with the sellers of all sorts of wares lining the streets. To get all the details on Rome’s shopping habits, and the ones that we still follow, read Claire Holleran’s Handbook to shopping in Rome.

Want to know more about the history of fashion and style? Check out some of our recents posts:

When Agnodice Became a Handbag

Unhairing in the 1800s: Animal Processing and Personal Care

Love to read? There are still a few days to sign up for our book giveaways!

April 24, 2015

Savor Flavor: The History of Artificial Flavoring

By Gastropod (Regular Contributor)

Why does grape candy taste so fake? What on earth is blue raspberry, anyway? And what is the difference between natural and artificial, at least when it comes to flavor?

Throughout human history, if you wanted to make a dish taste like strawberry, you had no choice but to add a strawberry. But in the 19th century, scientists began to understand how to synthesize flavor chemicals, whether from plants or from byproducts of coal processing, to evoke familiar flavors. While the technology to evaluate the flavor molecules of a particular food have become increasingly sophisticated in the past century, the basic concept of synthetic flavor has remained unchanged. Until now. In this episode of Gastropod, molecular biologists explain how they’re designing yeasts to ferment the tastes of the future.

Natural vs. Artificial

Let’s start with a graham cracker. Just like Sylvester Graham back in 1829, if you’re baking at home, you’d probably use coarse-ground whole-wheat flour, wheat bran, and wheat germ. These, along with some honey for sweetness, would give your graham crackers their distinctive toasty, malty, and slightly nutty flavor. If you’re making them by the billion, however, at a Nabisco or Keebler factory, the ingredients list looks a little different. That extra wheat germ and bran contain natural oils with a tendency to go rancid—but, when you cut them out to gain shelf-life, you lose the flavor.

Fortunately, there’s an easy solution: you can add all that flavor back with just a touch of a light yellow, crystalline powder called 2-acetylpyrazine. This is an aromatic, carbon-based chemical, known by flavorists as the “graham-cracker” flavor. It occurs naturally in nuts and toasted grains; as the vital ingredient giving factory-made graham crackers their signature flavor, it can either be extracted from a plant or synthesized using petrochemical derivatives.

The major difference is that 2-acetylpyrazine produced by performing chemical reactions on plant matter costs about $25 per lb—compared to the $5 or $6 per lb it costs to produce the kind whose raw ingredients come in a drum.

However, using the cheap version comes with another, increasingly significant cost: it means you have to include the words “artificial flavor” on your graham cracker ingredients list. Under FDA rules, if the raw material to make your flavor chemical comes from a plant, animal, or edible yeast, it’s “natural,” for the purposes of labeling. If it comes from anything else, it’s artificial. And consumers increasingly don’t want to buy things that are “artificial.” In fact, Michelle Hagen, a senior flavorist at Givaudan, the world’s largest fragrance and flavor company, told Gastropod that, despite the cost savings, she hasn’t used a single artificial chemical in her flavorings for the past four years—because the soda companies she mostly works with know that customers are turned off when they see that word on a label.

However, using the cheap version comes with another, increasingly significant cost: it means you have to include the words “artificial flavor” on your graham cracker ingredients list. Under FDA rules, if the raw material to make your flavor chemical comes from a plant, animal, or edible yeast, it’s “natural,” for the purposes of labeling. If it comes from anything else, it’s artificial. And consumers increasingly don’t want to buy things that are “artificial.” In fact, Michelle Hagen, a senior flavorist at Givaudan, the world’s largest fragrance and flavor company, told Gastropod that, despite the cost savings, she hasn’t used a single artificial chemical in her flavorings for the past four years—because the soda companies she mostly works with know that customers are turned off when they see that word on a label.

Enter the (Genetically Engineered) Yeast

Until recently, the natural flavors that Hagen uses would, for the most part, have been extracted from a plant; a handful of rarer ingredients, more often used in perfumery, would have come from animal sources. Today, advances in genetic engineering, combined with the growing consumer demand for natural flavors, are creating an intriguing new option for the world’s flavorists. In the past, the mention of “edible yeast” in the FDA definition of natural flavors typically referred to savory yeast extracts; now, designer yeasts are beginning to pump out vanilla, saffron, and even grapefruit flavors.

For this episode, Gastropod visited Ginkgo BioWorks, one of a new wave of companies redesigning yeasts to produce fragrance and flavor chemicals. As Christina Agapakis, a scientist, writer, and artist who recently joined Ginkgo’s staff, explained, the biology behind genetically modifying microbes to produce other, useful chemicals is not new. More than three decades ago, in 1978, biotech companies successfully inserted genes into bacteria to produce human insulin, meaning that diabetics need no longer depend on a close-enough version extracted from pig pancreases. In 1990, the FDA approved rennet made by inserting cow genes into E. coli bacteria; today, more than 90 percent of all cheese in the U.S. and U.K. is made using this bio-engineered product, rather than natural rennet found in the stomach linings of calves.

What is new, Agapakis told Gastropod, is “the ability to create flavors.” Rather than inserting the single gene that codes for the insulin protein, she explained, “to make a flavor, you might need five or ten different enzymes that are creating a whole pathway and are really shifting the metabolism of the yeast.” Fitting all those genes together so that what works in a plant to produce flavor also works in a yeast cell is challenging. Ginkgo has been developing its first yeast-fermented ingredient—a rose oil for the fragrance industry—for a couple of years now.

What is new, Agapakis told Gastropod, is “the ability to create flavors.” Rather than inserting the single gene that codes for the insulin protein, she explained, “to make a flavor, you might need five or ten different enzymes that are creating a whole pathway and are really shifting the metabolism of the yeast.” Fitting all those genes together so that what works in a plant to produce flavor also works in a yeast cell is challenging. Ginkgo has been developing its first yeast-fermented ingredient—a rose oil for the fragrance industry—for a couple of years now.

In fact, as organism designer Patrick Boyle explained, the main reason that the Ginkgo “foundry” is filled with liquid-handling robots and high-tech machines is to help him and his colleagues rapidly run through all the tweaked yeasts that don’t work. “Failure is usually not very dramatic,” he told Gastropod. “It’s just that we end up with a yeast that looks a lot like the yeast we started with.”

Still, a Swiss company called Evolva has recently brought the first of these “cultured flavors” to market: vanillin, the main ingredient in the world’s most popular flavor. Ginkgo’s rose oil smells pretty sweet, and the Boston-based company has half a dozen more flavor ingredients in the pipeline. And scientists in Austria just announced that they have successfully tweaked yeast to produce the key flavor chemical in grapefruit.

The Future of Flavor

Redesigning yeast to create flavor molecules offers some potential benefits. For starters, fermentation requires none of the harsh chemicals that are often used to extract essential oils from plants or react with petrochemical precursors. Engineered yeast also offers the possibility of democratizing rare, expensive flavors, like saffron, and, Patrick Boyle points out, it can “relieve some of the supply issues that come from using really rare plants.”

But the main attraction of this new technology for food companies is that the resulting flavors can legally be labelled as “natural”—they are produced by a yeast, after all. What’s more, because there is no yeast left in the final product, cultured flavors actually don’t contain genetically modified organisms.

Still, companies are nervous—Michelle Hagen at Givaudan told Gastropod that she hadn’t worked with any of these cultured flavors yet, and both Nestlé and General Mills responded to pressure from Friends of the Earth by pledging not to use cultured vanillin. In a press release, Friends of the Earth argued that using yeast to produce vanillin would threaten the livelihood of vanilla bean farmers in Madagascar, as well as the continued existence of the rainforest in which the vanilla orchid grows. But, as Patrick Boyle pointed out, the world demand for vanillin far outstrips the quantity of vanilla beans grown each year, and the synthetic and real vanilla industries have already managed to co-exist for more than a century.

Debates over natural vs. artificial aside, perhaps the most interesting aspect of these designer yeasts is the potential they offer for creating entirely new flavor experiences. For Christina Agapakis, the opportunity to learn more about the genes and pathways that plants use to express flavor will, she hopes, lead to productive collaborations with fruit and vegetable breeders—and increased deliciousness in the field as well as in the lab.

Listen to this episode to understand how the flavor industry got started and how designer yeasts could one day allow us to get closer to the taste of extinct, long-forgotten species—or even a Paleo flavor palette of pre-domestication plants and animals.

Gastropod is a new podcast hosted by award-winning science journalist Cynthia Graber and Edible Geography-author Nicola Twilley.

April 23, 2015

Posh Prisoner

By Daisy Hay (Guest Contributor)

In the first decades of the nineteenth century Surrey Gaol in south London was one of the largest prisons in England. It held a mixture of common criminals and debtors, who lived in and around the gaol with their families. Its governor, Mr Ives, ran his establishment as a flourishing business, charging prisoners fees for ale, the services of prostitutes, the removal of chains, and even for release on acquittal by a court.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century Surrey Gaol in south London was one of the largest prisons in England. It held a mixture of common criminals and debtors, who lived in and around the gaol with their families. Its governor, Mr Ives, ran his establishment as a flourishing business, charging prisoners fees for ale, the services of prostitutes, the removal of chains, and even for release on acquittal by a court.

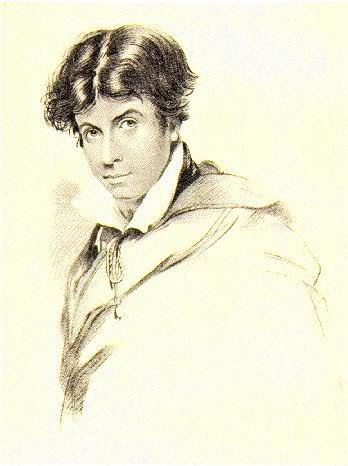

When the liberal journalist Leigh Hunt arrived at Surrey Gaol in 1813 to start a two year sentence for libelling the Prince Regent, he posed the prison authorities with a problem. Since he was writing about his incarceration every week in his newspaper, The Examiner, they couldn’t keep him in the spartan conditions endured by other prisoners. So they allocated him two rooms in the old infirmary, and allowed him to summon the decorators. Hunt installed crowded bookshelves and a piano, screened the barred windows with venetian blinds and covered the walls with rose-patterned wall-paper. Six weeks after the beginning of his sentence, he was ready to receive visitors.

His friends made their way through the dirty London streets and the prison’s dark corridors to find him settled in a riot of colour and comfort. He sat in splendidly appointed rooms, a fairy-tale king holding court in a bower of his own creation. His cell became an unlikely literary salon, and a refuge – for both the prisoner and his visitors – from the cares of the world.

Daisy Hay lives in London. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation

Daisy Hay lives in London. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest Generation

is her first book.

Image: Leigh Hunt, Engraved by H. Meyer from a drawing by J. Hayter

April 22, 2015

Olmstead, the Environmentalist

By Justin Martin (Guest Contributor)

In researching my latest biography, Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted, I was struck by the extent to which the celebrated landscape architect was also a pioneering environmentalist. Best known for crafting urban spaces – New York’s Central Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace – Olmsted was also deeply involved in saving wild places.

Helping preserve Yosemite is one of his greatest accomplishments. Beginning in 1864 – at a time when only a few hundred non-Native Americans had ever set foot in the valley – Olmsted made a series of visits. He was awestruck by the epic scenery, but also recognized how easily the place could be spoiled.

Helping preserve Yosemite is one of his greatest accomplishments. Beginning in 1864 – at a time when only a few hundred non-Native Americans had ever set foot in the valley – Olmsted made a series of visits. He was awestruck by the epic scenery, but also recognized how easily the place could be spoiled.

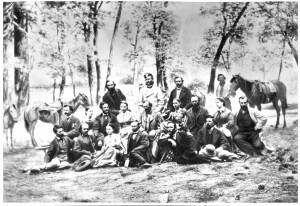

In 1865, Schuyler Colfax, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, embarked on a cross-country journey with a visit to Yosemite slated as the highlight. Speaker Colfax was accompanied by a number of journalists. As it happens, Olmsted saw a mention in a paper about Colfax’s planned Yosemite visit. He arranged to meet up with the party to act as a guide. Olmsted also drafted an 8,000-word treatise about Yosemite.

The Colfax party (Olmsted is front row, second from left in the photo) hiked and swam. They sang rollicking Civil War anthems such as “John Brown’s Body.” And one evening, with everyone gathered around the campfire, Olmsted gave a “spontaneous” reading of his treatise. It was filled with unique ideas, such as the need for an enlightened government to protect natural wonders. Remember, this was 1865, decades before a national park system even existed. “The establishment by the government of great public grounds for the free enjoyment of the people [is a] political duty,” Olmsted told the gathering.

Of course, the assembled journalists produced accounts of their visits to Yosemite. Several even wrote books. Invariably, their writings were full of ideas – Olmsted’s ideas – about the need to preserve wild places and the vital role government should play.

In 1906, Yosemite became a national park, thanks to the tireless efforts of naturalist John Muir. But Olmsted gets credit for being one of the first people to call for the valley’s preservation. Olmsted, the pioneering environmentalist, also helped preserve Niagara Falls and the vast Pisgah forest in North Carolina.

Justin Martin is a journalist and the author of several biographies. He was married in Central Park, Olmsted’s masterpiece. He lives in Forest Hills Gardens, NY, a neighborhood designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.

Justin Martin is a journalist and the author of several biographies. He was married in Central Park, Olmsted’s masterpiece. He lives in Forest Hills Gardens, NY, a neighborhood designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.