Holly Tucker's Blog, page 34

April 21, 2015

The Fur Trapper Who Became an Accountant

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

History stories hide in the most unexpected places. I was recently out walking in my neighborhood and stopped at one of those Little Free Libraries, which are small public repositories at which anyone can place an unwanted book or pick one up. I saw a title that caught my attention: Six Months in the Wilderness: The Adventures of a Young Trapper in Northern Minnesota by Michael W. Raihala.

Michael W. Raihala, who spent six months in the wilderness

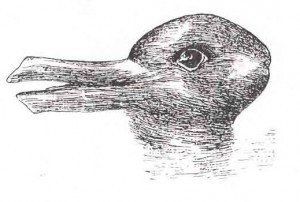

I pulled out the book and turned to the author’s photo on the back cover, anticipating someone who looked like Kit Carson. Instead, I saw the portrait that accompanies this post. This was the young trapper? This man spent six months in the wilderness?

As I learned from paging through this book, which was issued by the vanity publisher Exposition Press in 1955, here was a history tale. Mr. Raihala was a retired banker and accountant who made a discovery while going through his possessions in storage. On the back side of an old roll of wallpaper, he found a diary he had kept as a teenager. In barely decipherable writing, it described a trip he had taken into the woods as a 16-year-old in the company of a weathered trapper named Joe. Together they hunted, trapped, and camped in the wilderness. The experience deeply influenced the boy and gave him a fierce love of the outdoors, but poor health forced him to abandon his dreams of living in the wilderness. Instead, he moved to Duluth as an adult and went into desk work. I Googled the author and learned that he died in 1961.

Only after bringing the book home did I notice that Mr. Raihala had signed my copy on the title page under the handwritten inscription, “To Gracie, Don and David, from Pops.” I’d love to find out how this book ended up discarded in a box along my afternoon walk.

Further reading

Raihala, Michael W. Six Months in the Wilderness: The Adventures of a Young Trapper in Northern Minnesota. Exposition Press, 1955. [Good luck finding a copy!]

Urban Wonders: How Paris Became Paris

By Joan Dejean (Guest Contributor)

Today’s tourists would never consider a visit to Paris complete unless it included a stop on one of its famous bridges to admire the city from a perspective unlike any other. When they do so, they are taking part in a ritual now four centuries old.

Today’s tourists would never consider a visit to Paris complete unless it included a stop on one of its famous bridges to admire the city from a perspective unlike any other. When they do so, they are taking part in a ritual now four centuries old.

In this image from the 1630s, two men are standing on Paris’ then newest bridge, the Pont Neuf. As modern tourists still do, they are gazing out over the Seine marveling at the beauty of the river and of the city’s built fabric extending out into the distance.

The view from Paris’ bridges is justly fabled today – it’s hard to imagine how remarkable it must have seemed in the early 17th century, when it was brand-new, as was the case when the original river tourists, such as the two pictured here, took up their perch. François Bernier, world traveler and one of the most influential travel writers of the 17th century, rated the vista from the Pont Neuf “the most beautiful and the most magnificent view in the world.”

Perhaps the panorama’s most remarkable aspect is the fact that every bit of it – from the bridge to the notable architecture that can be admired when standing on it – was not only very recent construction, but it had all been constructed in record time.

Perhaps the panorama’s most remarkable aspect is the fact that every bit of it – from the bridge to the notable architecture that can be admired when standing on it – was not only very recent construction, but it had all been constructed in record time.

In 1600, roughly a half-century before Dutch artist Hedrick Mommers painted this view of the Pont Neuf and the panorama of Paris, none of it yet existed. The city was still emerging from decades of war between Protestants and Catholics. Its cityscape, like its economy, was in ruins. But by 1650 all that destruction had been put firmly in the past, as Mommers’ canvas clearly shows. In the course of a mere century, Paris was transformed. By the end of the 17th century, Paris had become a city people dreamed of visiting and had acquired the reputation it has enjoyed ever since: that of being an almost magical place.

I wrote How Paris Became Paris because I wanted all those who love Paris today to know that so many of its characteristic wonders and marvels were introduced not in the 19th century by Baron Haussmann as is now so often said, but a full two centuries earlier. By 1700, Paris had already become Paris.

Joan Dejean is Trustee Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of ten books on French literature, history, and material culture, including The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual and the Modern Home Began and The Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour.

Joan Dejean is Trustee Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the author of ten books on French literature, history, and material culture, including The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual and the Modern Home Began and The Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of How Paris Became Paris in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on April 30th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

April Book Giveaways

Thomas Fleming, The Great Divide:The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation

Douglas Boin, “Coming out Christian in the Roman World”

Joan Dejean, “How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City”

April 20, 2015

Women and Shipwrecks: Surviving ‘The Medusa’

by Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Shipwrecked women were popular in early fiction and drama. Stories of women washed up on foreign shores fascinated early modern readers. In painting, the image of a barely clothed female figure tossed up on a beach was also a favorite subject. Unlike their male counterparts who were often depicted stunned but alive and staggering toward some kind of future, shipwrecked women were usually unconscious or dead, as in the painting The Storm by Théodore Géricault.

Shipwrecked women were popular in early fiction and drama. Stories of women washed up on foreign shores fascinated early modern readers. In painting, the image of a barely clothed female figure tossed up on a beach was also a favorite subject. Unlike their male counterparts who were often depicted stunned but alive and staggering toward some kind of future, shipwrecked women were usually unconscious or dead, as in the painting The Storm by Théodore Géricault.

Perhaps the world’s most famous painting of survivors of a real shipwreck is another one by Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa (1819). The wreck of the frigate off the coast of Senegal on July 2, 1816 became a huge media event back home in  France. Bestselling accounts were written by two of the male survivors, Sauvigny and Corréard. Stories of the crew who abandoned the passengers, and then selectively killed off many who had managed to board the life raft caused great outcry in France. The disaster became a political scandal, as well, when it became known that the inexperienced captain had been given his command as the result of corrupt connections with the Bourbon regime.

France. Bestselling accounts were written by two of the male survivors, Sauvigny and Corréard. Stories of the crew who abandoned the passengers, and then selectively killed off many who had managed to board the life raft caused great outcry in France. The disaster became a political scandal, as well, when it became known that the inexperienced captain had been given his command as the result of corrupt connections with the Bourbon regime.

In the political storm that followed, people lost sight of the fate of some of the ordinary passengers who had survived the disaster. One of these was a young woman named Charlotte Picard, an 18-year-old who had been travelling on the Medusa with her family, accompanying her father who was going to Africa to serve as a clerk in the French colonial administration. Of the nine family members onboard the doomed ship, only four survived the wreck and the immediate months that followed.

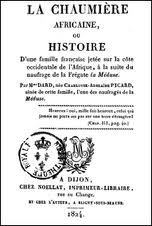

In 1824 Charlotte decided to publish her own account of the events and her family’s subsequent life on an island off the west coast of Africa, titled La Chaumière africaine (The African Cottage). In it she made sure to correct details that had previously circulated. Her rendering of the female survivors is anything but pathetic. The accounts written by Sauvigny and Corréard had lingered over descriptions of the female victims who had been lost to the waves, and boasted about the ones who they personally had been able to save. Charlotte tells her own extended story of terror and adventure on the small boat that her father managed to board with his family, after they were all turned away from the life raft. When they at last approached a shore their boat capsized, and all were washed up on the beach.

In 1824 Charlotte decided to publish her own account of the events and her family’s subsequent life on an island off the west coast of Africa, titled La Chaumière africaine (The African Cottage). In it she made sure to correct details that had previously circulated. Her rendering of the female survivors is anything but pathetic. The accounts written by Sauvigny and Corréard had lingered over descriptions of the female victims who had been lost to the waves, and boasted about the ones who they personally had been able to save. Charlotte tells her own extended story of terror and adventure on the small boat that her father managed to board with his family, after they were all turned away from the life raft. When they at last approached a shore their boat capsized, and all were washed up on the beach.

Charlotte Picard and her little band of relatives lived in Senegal for two years, confronting illness and starvation. They managed to keep themselves going until 1820, when she returned to France. Her version of the famous disaster went beyond the shipwreck story, showing how a woman was able to pick herself up and walk off the beach, making a new life for herself and those who remained with her.

For further reading:

Charlotte (Picard) Dard, La Chaumière africaine ou histoire d’une famille française jetée sur la côte occidentale de l’Afrique à la suite du naufrage de la frégate “La Méduse”, ed. Doris Y. Kadish. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2005.

Jonathan Miles, The Wreck of the Medusa. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007.

April 18, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xviii

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Here at Wonders & Marvels, we are big supporters of the Digital Humanities (we are a blog after all!). It seems that every day people are coming up with new ways to illuminate the past using the most modern technologies. This week we are happy to share a few of the newest and best digital innovations.

There’s an App for That

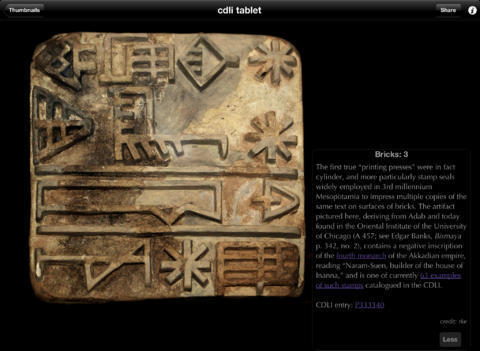

History is going mobile! With an increasing number of us glued to our phone and Ipad screens, there are an increasing number of apps that help you explore history. But which ones are the most useful? Luckily, Kate Wiles has already done the testing for us in History Today’s list of The Best History Apps. This list highlights something for everyone from the Cdli Tablet’s virtual exploration of ancient Mesopatamia to the Braginsky Collection that holds eight centuries of Jewish manuscripts and texts.

History is going mobile! With an increasing number of us glued to our phone and Ipad screens, there are an increasing number of apps that help you explore history. But which ones are the most useful? Luckily, Kate Wiles has already done the testing for us in History Today’s list of The Best History Apps. This list highlights something for everyone from the Cdli Tablet’s virtual exploration of ancient Mesopatamia to the Braginsky Collection that holds eight centuries of Jewish manuscripts and texts.

Another app that caught our eye takes full advantage of the mobility today’s tech offers. Women on the Map works with Google’s Field Trip app will buzz when you are close to a place where a woman made history. With the goal of narrowing the gender gap in history, the app has already researched 100 women who made history around the world and continue to add to the collection.

There’s a Map for That

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a good map could be worth even more. Charting history is easier than ever with new cartographic innovations.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a good map could be worth even more. Charting history is easier than ever with new cartographic innovations.

A huge benefit of the internet age for historians is the accessibility of documents from all over theworld. One impressive collection, the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection has recently added more than 2,000 new pictoral maps to its online collection. These gorgeous pictorial maps, like the map visualizing the tea trade on the left, help researchers and readers alike envision history in a myriad of ways.

It is oft en hard to visualize the magnitude of historical events, but with digital maps historians can easily illustrate history’s movements. The Bomb Sight Project’s new map helps historians to visualize the impact of World War II by seeing where bombs fell in London during the war. The result is astounding: a vision of London practically covered in red bombs.

en hard to visualize the magnitude of historical events, but with digital maps historians can easily illustrate history’s movements. The Bomb Sight Project’s new map helps historians to visualize the impact of World War II by seeing where bombs fell in London during the war. The result is astounding: a vision of London practically covered in red bombs.

If this has whetted your appetite to dig into some history, take a look at our recent posts:

Even though we love all things digital, we are a fan of hard-copy books too! Sign up for our giveaways!

April 17, 2015

Hiding in Plain Stripe

Dazzle Ship, Tobias Rehberger, 2014. Image credit – Chris Wainwright

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor) and Margaret Walker

Anyone wandering along London’s South Bank since July 2014 will have noticed the remarkable ‘graffiti’ed ship docked across the river opposite the Tate Modern. The ship is one of three surviving First World War naval vessels, HMS President (1918). It was painted by the German artist Tobias Rehberger in the “dazzle style” invented during the First World War to camouflage merchant vessels and protect them from torpedo attacks.

Razzle Dazzle

After the declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany in January 1917, the British navy was acutely aware of the need for camouflage to protect ships crossing the Atlantic and the Channel with supplies. Attempts to make the ships less visible proved unsuccessful, and the artist Norman Wilkinson, then serving in the Navy, instead proposed the “Dazzle” technique. The premise behind Dazzle was that bold patterns and stripes could create optical illusions that would trick the human eye, and disrupt the ability of the German torpedo operator –viewing from a periscope—to predict where to shoot. (Operators had to estimate size, speed, direction of travel, and distance from the target ship to calculate where it would be when the torpedo reached it, and consequently perception was crucial to an effective strike). Wilkinson worked with a team of five designers and 11 female art students in a workshop in the Royal Academy in London to create small wooden prototypes, and a miniature periscope through which to view them, as King George V did when he visited the studio in 1918.

Into the Vortex

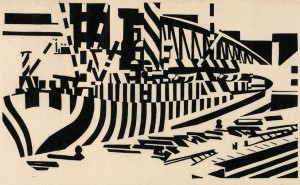

In Dry Dock 1918. Woodcut paper. Wadsworth, Edward Alexander (ARA) (1889 – 1949) http://www.1418now.org.uk/commissions...

Once the British Admiralty chose to adopt the Dazzle technique for merchant vessels in October 1917, Wilkinson appointed the artist Edward Wadsworth to oversee the painting in the shipyards in Liverpool and Bristol. Wadsworth had been a major figure in the Vorticist avant-garde art movement, and the similarity of Vorticism to the Dazzle designs is striking, suggesting that Wadsworth’s influence on the Dazzle ships was substantial. Margaret Walker has argued that Wilkinson not only hired Wadsworth based on his familiarity with Wadsworth’s pre-war artwork, but that the Dazzle ship’s Vorticist-looking designs played a central role in the “mainstreaming” of modernist visual culture in Great Britain. The modernism of the Dazzle ships was certainly not lost on educated contemporaries: one New York journalist quipped in reference to Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase” (1912) that the Dazzle Ship rather resembled “A Drunken Sailor Falling down a Hatchway.” The Dazzle camouflage technique was employed by American merchant vessels too, and was known in the USA as “Razzle Dazzle.” Although it is now most closely associated with ships, it was applied in other contexts too.

“A Flock of sea-going Easter Eggs”

© IWM (Art.IWM ART 4030) NORMAN WILKINSON image: A view of a distant convoy of ‘dazzle’ painted camouflaged ships at sea. By day, the ships are obviously visible, though from a distance the ‘dazzle’ effect stills works to confuse the number and outline of the different ships in the convoy. Imperial War Museum, Art Section commission

Rehberger’s South Bank dazzle ship is striking enough alone, but the technique was considered most effective for convoys, functioning like the stripes on a herd of zebra to confuse a predator and make individuals hard to identify and target. A convoy of dazzle ships in dock must have been a remarkable sight: a contemporary journalist described a group as a: “a flock of sea-going Easter Eggs.” Data collected by the British Navy suggested that Dazzle was only modestly successful at protecting convoys, but the practice was continued for reasons of morale, and by the end of the war, there were 2,300 dazzle ships in service, each with a unique Dazzle design.

Margaret Walker’s MSc thesis at the University of Edinburgh is entitled “Art of Illusion: Vorticism, Dazzle Ships and the Mainstreaming of Modern Art in Britain during the Great War” (August 2013)

On the history of camouflage, see: Roy R. Behrens, Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage (Bobolink Books, 2009)

Tobias Rehnberger’s Dazzle Ship will be docked opposite the Tate Modern until July 2015:

http://www.1418now.org.uk/commissions/dazzle-ship-london/

Margaret Walker is the art curator assistant at the Vanderbilt Fine Arts Gallery. Before gaining her MSc in History of Art, Theory and Display at Edinburgh University, she studied History at Princeton University.

April 16, 2015

America’s First Pop Psychologist

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels Contributor

When Joseph Jastrow died in 1944 at age 80, he was almost a forgotten figure in American psychology and certainly an irrelevant one to many minds. Decades earlier he had given up full-time work in academe, and his most recent writing, an analysis of the psychology of Adolf Hitler, had been ignored.

Joseph Jastrow (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet for many years he had been America’s preeminent pop psychologist, finding ways to explain and interpret psychological ideas to lay audiences interested in bringing the wisdom of this new science into their daily lives. Drawn away from experimental psychology by personal tragedies, he wrote popular books and contributed to Harper’s Monthly and other consumer magazines. The Polish-born Jastrow was thus a predecessor of such recent pop psychologists as Joyce Brothers, M. Scott Peck, Wayne Dyer, and “Dr. Phil” McGraw.

Short and bespectacled, Jastrow was the first American to receive a doctorate in psychology, in 1883. He joined the faculty of the psychology department at the University of Wisconsin. There he built the first psychology laboratory that specialized in investigations of the senses. He examined involuntary movement, stereoscopic vision, deception, hypnosis, the mental acuity of conjurers, reasoning processes, and the formation of judgments. His studies of optical and psychological illusions carried his name around the world, and several of his illusions — still known as Jastrow Objects — continue to appear in psychology textbooks.

By 1900, his passion for experimental psychology had run dry and the stresses of his career brought him a mental breakdown and the need to seek medical care. (A newspaper headlined a story on Jastrow’s troubles as “Famous Mind Doctor Loses His Own.”) After a year away from academics, he focused his attention on popularizing psychology rather than continuing to labor in the laboratory. Later, the death of his son in World War I and his wife’s death added to Jastrow’s depression. He now tapped his talent for presenting psychology to the public, a skill he had cultivated years earlier at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. At that public gathering — the same one at which the serial killer H.H. Holmes found his victims — Jastrow created an exhibit that included participatory activities, including psychological tests that visitors could take on the spot. One of his test-takers was the teenaged Helen Keller, who received from Jastrow the first thorough examination of her sensory faculties.

The Rabbit-Duck Illusion, one of the best known Jastrow Objects. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1901 Jastrow wrote Fact and Fable, the first of his many popular books on psychology. One of his favorite topics was the deceptive performances of mediums and psychics, and he joined with the stage entertainer Harry Houdini in jousting with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and others who believed in the supposed talents of spiritualists. Meanwhile, although Jastrow came off as boring and incomprehensible in the classroom, he developed into an entertaining speaker on the popular lecture circuit. He gained fame for his lectures on “the will to believe,” his phrase for our tendency to let authority and sensationalism persuade us even when scientific evidence suggests we shouldn’t.

Toward the end of his life, Jastrow became a well known media personality. Soon after resigning from his teaching position at the University of Wisconsin, from which he had grown distant, Jastrow began writing a syndicated newspaper column, “Keeping Mentally Fit,” in 1927, and during the 1930s he refashioned his topics for radio audiences. His final books bore such titles as Piloting Your Life, Effective Thinking, and Sanity First — early entries in today’s self-help category. His last volume, Hitler: Mask and Myth, never found a publisher. By the end, audiences viewed his style as old-fashioned and formal, but he introduced countless people to the illuminating potential of the study of human behavior. “There was no exploiting just for the sake of sales or publicity,” one of his eulogists concluded. “Jastrow always left a dignified impression of psychology and did nothing to bring the science into disrepute.” Not all of today’s pop psychologists can claim the same.

Sources:

Behrens, Peter J. “War, Sanity, and the Nazi Mind: The Last Passion of Joseph Jastrow.” History of Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 266-284.

Blum, Deborah. “Mind Tricks for the Masses.” On Wisconsin Magazine, Summer 2010.

Pettit, Michael. “Joseph Jastrow, the Psychology of Deception, and the Racial Economy of Observation.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 43(2), pp. 159-175.

Pillsbury, W.B. “Joseph Jastrow, 1863-1944.” The Psychological Review, Vol. 51, No. 5, pp. 261-265.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in October 2012.

April 14, 2015

“The Christians” Party in Rome

By Douglas Boin (Guest Contributor)

The birthday party was over, but the hangover was fierce.

On April 21st, 248 A.D., the Emperor Philip had celebrated Rome’s 1,000th anniversary. Exotic elk, hippopotami, giraffes, lions, and tigers were put on parade in the Circus (or put to death in the Colosseum). It was a fête befitting the citizens of a diverse empire. And then Philip, tragically, was killed. Unity would not come easy in the years that followed. When Emperor Decius, in 250 A.D., announced a Mediterranean-wide campaign asking citizens to gather in their cities, participate in local sacrifices, and share in the banquet that followed, some citizens balked. They worshipped Jesus the Messiah, they said. They couldn’t be expected to do what other citizens were doing. “Christians” were different.

It’s a compelling way to tell the story: Christians fought the tyranny of persecution, and they eventually won the free right to practice their faith as they wished. Only history’s a little more complicated.

As I show in my new book, Coming Out  Christian in the Roman World, many Christians did exactly the thing generations of historians have assumed they did not do. They participated in Roman festivals and civic banquets. We know because many of their own peers vilified them for it. Curiously, though, we’ve never tried to see history from their perspective. And that’s where the story gets really interesting.

Christian in the Roman World, many Christians did exactly the thing generations of historians have assumed they did not do. They participated in Roman festivals and civic banquets. We know because many of their own peers vilified them for it. Curiously, though, we’ve never tried to see history from their perspective. And that’s where the story gets really interesting.

In Roman Spain, two men in particular—their names are Martial and Basilides—were at the forefront of an outreach campaign showing their friends and neighbors that they could be Christian and Roman at the same time. Martial and Basilides both attended the emperor’s call for sacrifice in 250 A.D. Martial himself probably took part in sacrifices regularly as part of his commitment to a local Roman social club, called in a Latin a collegium, or guild. Archaeological remains of these guilds have been identified all throughout the Mediterranean. The city of Ostia, the harbor town of Rome, offers several examples. Guilds usually had rooms for banquets and, more importantly, temples where the club’s patron gods were worshipped.

Martial was a member of one of these organizations. He was also a Christian bishop. He lived a hyphenated life. Martial’s ability to build bridges with people in town—by attending “pagan” sacrifices and participating in Roman civic life—also did not sit well with other Christians. One bishop in North Africa even considered his compromise, like Basilides’, a sign that “the end of the world” was coming.

History, however, is not just an account of who shouted the loudest. It also includes the quieter voices we might have overlooked. And that’s why Martial and Basilides are so important to the history of the Roman Empire. Many people assume that Christians were incapable of living as citizens in the Roman world and that, when the followers of Jesus eventually moved into the palace, they finally succeeded in “Christianizing” it. The evidence I’ve collected in my book suggests a much different picture. Many Christians didn’t need to “Christianize” anything, and their lives change how we tell Roman history.

Douglas Boin is an archaeologist and a historian of the ancient Mediterranean world who teaches at Saint Louis University. In his research and public writing, he explores how ancient texts and artifacts can help us reconstruct relations between Jews, Christians, and non-Christians throughout the Roman Empire. He is the author of Ostia in Late Antiquity and, most recently, a general history book, Coming Out Christian in the Roman World: How the Followers of Jesus Made a Place in Caesar’s Empire, available from Bloomsbury Press.

Douglas Boin is an archaeologist and a historian of the ancient Mediterranean world who teaches at Saint Louis University. In his research and public writing, he explores how ancient texts and artifacts can help us reconstruct relations between Jews, Christians, and non-Christians throughout the Roman Empire. He is the author of Ostia in Late Antiquity and, most recently, a general history book, Coming Out Christian in the Roman World: How the Followers of Jesus Made a Place in Caesar’s Empire, available from Bloomsbury Press.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Coming out Christian this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on April 30th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

April Book Giveaways

Thomas Fleming, The Great Divide:The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation

Douglas Boin, “Coming out Christian in the Roman World”

Joan Dejean, “How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City”

Image: Getty Open Content Program. Unknown, “Fragment of a Fresco Panel with a Meal Preparation,” Roman, 100 – 150 A.D., Fresco, 69.5 x 127 x 3.5 cm (27 3/8 x 50 x 1 3/8 in.), 79.AG.112.

April 13, 2015

When Agnodice Became a Handbag…

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

I am always interested in how the past is used in advertising. Whether that’s in a trade name (when I grew up, ‘Vim’ was used for scrubbing all sorts of surfaces and it was fun when I started to study Latin and found out it meant ‘Force’) or in an image (Greek columns as signifying a ‘classy’ if not a classical product), the ancient world is never far away. There’s a security firm in Vienna called Sparta,  for example – which has all the right sense of living a simple life, being careful with your money, being strong…

for example – which has all the right sense of living a simple life, being careful with your money, being strong…

As readers of this blog know, I have a bit of a thing about the mythical ancient figure, Agnodice. I’ve written half a book about her. In the only ancient source in which she features, she appears in a story about how ‘the ancients had no midwives’ until she came along – but the rest of the story is about her disguising herself as a man and learning not midwifery, but medicine in general. At various points in the story, generations of readers have translated the Latin differently according to whether they want her to be the ‘first midwife’ or the ‘first female physician’. That second label is not straightforward – if she is supposed to be the first woman who becomes a physician, then what sort of physician does she become? A woman who can treat any patient, or a woman who can only treat her fellow women?

Like any scholar today, I’ve set up some Google alerts to let me know when key words from my research interests pop up on the web. I don’t get a lot for ‘Agnodice’. But one day recently I did – and it’s a great one. Because now you can buy a handbag called Agnodice!

In designing this bag with its ‘elegance and savoir-fair’, Porsche Design seem unaware of Agnodice’s main claim to fame: her willingness to lift up her clothes to prove she is a woman, a gesture she first does to a female patient who doesn’t want to discuss her medical problems with a man, and then repeats when brought to court on a charge of gaining her popularity as a physician by seducing women patients. But never mind. The company is quite up-front about why they picked the name. It’s not just the high-class nature of the product, with its ‘outstanding craftsmanship, luxurious leather and amazing brass metal details’. Rather, it’s the capacious nature of the bag; the design ‘is reminiscent of a traditional doctor’s bag and was inspired by the Greek physician Agnodike’.

So, in the long history of the debate over whether Agnodice was a midwife or a physician, Porsche Designs comes down on the side of a physician. And I have to say that I agree with them. The story gives every sign of being about a woman learning medicine and treating other women for a range of medical conditions.

The quality of the product is intended to ‘make Agnodice your perfect companion’. At 1790 €, however, much as I like Agnodice, I don’t think I can afford friends like that!

April 11, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xvii

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Medical headlines have captured our attention for the past year. To vaccinate or not to vaccinate? How do we stop the Ebola epidemic? Despite the global health challenges we still face, healthcare today would be considered modern marvel by our ancestors. Yet, the problems we face today are not so different from the issues they faced.

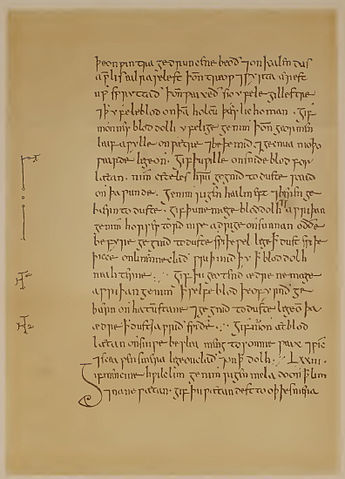

Bald’s Leechbook

Not-So-New Problems, Ancient Solutions?

Antibiotics have saved many lives, but an unintended result of the prevalent use of these treatments are so called antibiotic-resistant “superbugs”. Could ancient remedies be the answer to these new superbugs? Researchers at the University of Nottingham hope so! An Anglo Saxon remedy of onion, garlic, cow bile, and wine derived from Bald’s Leechbook has shown to be effective against some of these superbugs in early trials. Turns out garlic is useful for more than warding off Vampires!

Another challenge facing our increasingly digitized healthcare system is how to keep a safe and accurate healthcare record. As it happens, keeping medical records is no new challenge. Turkish historians recently discovered a medical consent form dating back to 1524. The consent form to relieve a bladder stone (a painful and dangerous procedure) is the oldest known documentation of that provides consent for a procedure, and relieves the physician of any legal responsibility should something go wrong (pictured below).

Sometimes modern medicine appears to focus on trivial breakthroughs like botox and viagra. Actually, the search for viagra started long before researchers stumbled on it. It turns out, medieval men were looking for a solution to erectile dysfunction over 1000 years prior to viagra’s invention. Ninth-century physician Ahmed Ibn al-Jazzar wrote on the origin of this issue and homeopathic ways to treat the condition.

A more serious issue that receives increasing attention today is mental illness. Unfortunately, the way that mental illness has been treated in the past is not really a model for our future. All Day’s recent feature covers the “horrible history” of Bedlam, the world’s most famous mental asylum. This article, filled with images of Bedlam like Hogarth’s “A Rake’s Progress”, traces the degeneration of Bedlam after the government overtook, and poorly managed, this infamous mental institution.

A more serious issue that receives increasing attention today is mental illness. Unfortunately, the way that mental illness has been treated in the past is not really a model for our future. All Day’s recent feature covers the “horrible history” of Bedlam, the world’s most famous mental asylum. This article, filled with images of Bedlam like Hogarth’s “A Rake’s Progress”, traces the degeneration of Bedlam after the government overtook, and poorly managed, this infamous mental institution.

Are you fascinated by medical history? Take a look at a few more posts on the topic right here on Wonders & Marvels:

Also, don’t forget to sign up for our monthly book giveaways!

April 9, 2015

Let’s Drink Like a Pope!

By Roger Collins (Guest Contributor)

Not long after his death in 1342 Benedict XII had his life written by a French monk, who took the precaution of remaining anonymous, as what he had to say about the pope was not flattering. ‘Hard’, ‘mean’, ‘hating friars’ and thinking all of his cardinals were liars, were just some of the accusations made. Our author also said that Benedict drank so much wine that he gave rise to the popular toast Bibamus papaliter, or ‘Let’s drink like a pope’!

Not long after his death in 1342 Benedict XII had his life written by a French monk, who took the precaution of remaining anonymous, as what he had to say about the pope was not flattering. ‘Hard’, ‘mean’, ‘hating friars’ and thinking all of his cardinals were liars, were just some of the accusations made. Our author also said that Benedict drank so much wine that he gave rise to the popular toast Bibamus papaliter, or ‘Let’s drink like a pope’!

This was not the first time that this particular pope had received a bad press. Before he was unanimously elected in 1334, he had been bishop of Pamiers, near Toulouse in south-western France, and there had led the inquisition in its investigation of Cathars or Albigensians in his diocese, most notably in the village of Montaillou. His detailed records of these interrogations, partly preserved in his own notebook now in the Vatican Library, provided the material for the famous French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie to reconstruct so much of the life and thought-world of that community in his book Montaillou of 1975.

Unsurprisingly, some of those who appeared before Bishop Jacques Fournier, as he then was, felt he was ‘the spirit of evil’, and ‘a demon infesting the land.’ One of them wished he ‘would fall into a precipice.’ For historians today, however, Benedict XII is a an austere reformer, who resisted the temptation to reward his own relatives in the way so many of his immediate predecessors and successors did, and who tried to impose higher standards of conduct in the Church; for example reproving the ‘infinite’ number of Spanish priests said to be living openly with their mistresses. Other contemporary authors, who shared his ideals, reported sadness at his death and miracles at his tomb. But his successor, who became Clement VI, was far more generally popular, as he quickly showed that his nature lived up to his name.

Roger Collins is author of Keepers of the Keys of Heaven: A History of the Papacy[image error]Keepers of the Keys of Heaven: A History of the Papacy (Basic Books).

Image: Pope Leo X, courtesy of Basic Books

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in March 2009.