Holly Tucker's Blog, page 36

March 19, 2015

Work Should Be More Like a Café

By W. Scott Haine & Jeffrey H. Jackson (Guest Contributors)

When Yahoo!’s president required employees to work from the office rather than home, she raised a fundamental question about where we generate our most innovative ideas. Do we need to work collaboratively to be inventive, or can we be inspired when we are alone?

When Yahoo!’s president required employees to work from the office rather than home, she raised a fundamental question about where we generate our most innovative ideas. Do we need to work collaboratively to be inventive, or can we be inspired when we are alone?

We suggest that in a creative economy, people need what we call “thinking spaces.” These sites offer two key elements: they provide time for individual thought, but they also encourage in-depth conversation. Innovation comes from a balance of both.

The original model for the “thinking space” was the café. Born in 17th century London, the modern café allowed thinkers to spend the day contemplating new ideas for the price of a drink. As hubs of human activity, patrons could also find others with whom to share and debate their thoughts. Cafés created the first “social networking sites” where innovators interacted in depth and in real time.

In the nineteenth century, cafés in cities like Paris, Vienna, Rome, and New York became famous for the cutting-edge artistic movements and fervent political ideologies generated there. Revolutionaries, philosophers, and artists all had their favorite haunts. Cafés were the incubators of “bohemianism,” the avant-garde practice of living on the edge for the sake of one’s highly idiosyncratic ideas even while trying to sell those ideas to a publisher or a gallery. Bohemian ingenuity was in many ways the origin point of the modern creative economy.

The innovations generated in cafés have shaped the world we live in. Cafés as thinking spaces continue to offer a model for how we can work in a creative economy where we’re all bohemians. Each of us needs privacy to cultivate our own unique voice and generate ideas, but we must refine those notions through conversation, brainstorming, and exchange with others. Without that balance, great ideas can suffer in silence or be subsumed in groupthink.

The innovations generated in cafés have shaped the world we live in. Cafés as thinking spaces continue to offer a model for how we can work in a creative economy where we’re all bohemians. Each of us needs privacy to cultivate our own unique voice and generate ideas, but we must refine those notions through conversation, brainstorming, and exchange with others. Without that balance, great ideas can suffer in silence or be subsumed in groupthink.

Ironically, despite the growing number of coffee shops in American cities and their historic role in creative exchange, cafés offering a blend of isolation and sociability have been replaced by sites where we are alone in public. Starbucks and many others have brought elements of the historic café tradition into the present, but most customers in these places cut themselves off from one another with earbuds and laptops. How many people truly discuss ideas with someone at Starbucks on a regular basis?

It doesn’t have to be this way. Cafés themselves can still offers inspiration, and encouraging interaction might be good for business. When one New Haven, Connecticut coffee shop banned laptops, business boomed as people came in for the human interaction rather than the wi-fi.

Local coffee shops provide a sign to place on the table inviting other people to sit down and talk. Nearly all university libraries and many office buildings offer a café where people gather. Meet-ups often happen in cafés and bars in order to bring people together and share new ideas. These new approaches to re-creating the café feeling represent a self-conscious effort to combat the tendency toward isolation and balance private thoughts with public conversation.

Business is emulating the café as well. Many offices, especially those in the high-tech sector, mimic important aspects of the café as a thinking space. Steve Jobs insisted that the corporate headquarters of Pixar allow random, spontaneous, serendipitous sociability. Such well-designed offices have proven to be some of the most creative places around.

The phenomenon of “co-working,” where freelancers or business travelers use a common space even though they are working on different projects or for different employers, is changing how many people conceive of the social nature of work. “Co-working” is based on the premise that we work best when we are in a community, even when our ideas are heading in different directions.

The phenomenon of “co-working,” where freelancers or business travelers use a common space even though they are working on different projects or for different employers, is changing how many people conceive of the social nature of work. “Co-working” is based on the premise that we work best when we are in a community, even when our ideas are heading in different directions.

An old-fashioned activity like talking is not efficient in modern technological terms, and itcertainly requires more than 140 characters or a status update. But as creativity increasingly becomes a necessity at work, the tried-and-true model of the café as a “thinking space” may provide a way to update an old idea for a new era.

W. Scott Haine teaches at the University of Maryland University College and Jeffrey H. Jackson is the J.J. McComb Professor of history at Rhodes College in Memphis. The authors are co-editors of the book The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy, and Vienna (Ashgate Press).

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in October 2013.

March 18, 2015

From Village Life to Palace Life

By Michelle Moran (Guest Contributor)

Delving into my characters’ lives by traveling to the places they visited and lived is one of the most rewarding aspects of writing historical fiction. For each of my books I’ve been lucky enough to be able to travel to the locations where my protagonists spent their lives. In some cases, little remains of where they lived. But in others, the monuments they built are still in existence. In the case of Sita, the narrator of my sixth book, Rebel Queen, the locations I visited while in India were incredibly varied.

Rani Laksmi, Queen of Jhansi

Unlike most women in the queen’s Durga Dal, an elite group of female guards hired to protect the Queen of Jhansi, Sita wasn’t born in a city. She was born in a village. Anyone who has visited a village in India knows that not much has changed in the hundred plus years since Sita’s birth.When I first arrived in my husband’s ancestral village of Itaara, it was like stepping back in time. The roads were unpaved, the houses made of both mud and brick, and the streets were lined with temporary shrines, each one tenderly fashioned from cow dung to honor the local gods. The women there covered their heads with scarves, called dupattas in Hindi, and when I fell violently ill after eating food cooked in the house we were visiting, I was told it was because one of the villagers had given me the evil eye.

Yes, there were satellite dishes protruding from the brightly painted walls of the houses, but inside, life wasn’t much different from the life Sita experienced. The villagers still slept on charpai, beds made of tightly woven rope (and the origin of the expression, sleep tight). And cow dung was still used to fuel fires. Contrast this with the life Sita experienced when she first became a member of the queen’s Durga Dal and you can see how varied research trips can be when trying to piece together a character’s world.

It’s impossible to know what Sita felt when she arrived in the city of Jhansi in order to become one of Rani Lakshmi’s guards, but she probably would have been as impressed as I was passing through gates built to accommodate the maharaja’s elephants. Although Jhansi’s former glory has been diminished by war and neglect, you can still see Rani Lakshmi’s palace today and visit the queen’s audience chamber where the most famous woman in India once held court. Her numerous temples, courtyards, and stables have been preserved, even her elaborately painted halls punctuated by windows that were covered in the summer with fragrant kusha grass.

It’s impossible to know what Sita felt when she arrived in the city of Jhansi in order to become one of Rani Lakshmi’s guards, but she probably would have been as impressed as I was passing through gates built to accommodate the maharaja’s elephants. Although Jhansi’s former glory has been diminished by war and neglect, you can still see Rani Lakshmi’s palace today and visit the queen’s audience chamber where the most famous woman in India once held court. Her numerous temples, courtyards, and stables have been preserved, even her elaborately painted halls punctuated by windows that were covered in the summer with fragrant kusha grass.

Coming from a village where her bed was made of rope and her only experience with bathing was a bucket, Sita would have been overwhelmed by the rani’s elaborate furniture and vast baths. From the exquisite gold jewelry to the stunning silk saris which even the queen’s guards were expected to wear, everything would have appeared dazzling to her.

It’s always fascinating to write about a character whose life changes radically. Sita’s transition from a village girl to a palace guard was great fun to research, and I hope readers will enjoy reading about it as much as I enjoyed writing it!

Michelle Moran is the international bestselling author of six historical novels, including Madame Tussaud, and her newest Rebel Queen.

Michelle Moran is the international bestselling author of six historical novels, including Madame Tussaud, and her newest Rebel Queen.

March 17, 2015

Laughing at French Smiles and Dentures

By Colin Jones (Guest Contributor)

T homas Rowlandson’s ‘Six Stages of Mending a Face’ (1792) shows the startling transformation of an ululating, toothless old harridan (in the top right of the image) into the coyest and smiliest young miss (bottom left). This savagely humorous image was – ironically no doubt – ‘dedicated with respect to the Hon.ble Lady Archer’. Lady Sarah Archer was one of London’s fast set which was notorious for their gambling habits. Rowlandson was thus reflecting the values of the growing campaign at this time targeting gambling as a solvent of aristocratic solvency and morals. A gender issue was also at play: the domestic ideology then emergent held that women belonged not at the gaming table but at the hearth.

homas Rowlandson’s ‘Six Stages of Mending a Face’ (1792) shows the startling transformation of an ululating, toothless old harridan (in the top right of the image) into the coyest and smiliest young miss (bottom left). This savagely humorous image was – ironically no doubt – ‘dedicated with respect to the Hon.ble Lady Archer’. Lady Sarah Archer was one of London’s fast set which was notorious for their gambling habits. Rowlandson was thus reflecting the values of the growing campaign at this time targeting gambling as a solvent of aristocratic solvency and morals. A gender issue was also at play: the domestic ideology then emergent held that women belonged not at the gaming table but at the hearth.

But there is a French influence here too which has escaped detection. Rowlandson was a regular visitor to Paris. On his most recent prior visit there in 1787, he is likely to have seen the ‘Self-Portrait’ that Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun displayed at the Louvre that year. The smiling portrait shocked connoisseurs within French high society and created quite a stir. Portraying a respectable woman opening her mouth to smile while revealing white teeth broke every rule in Western art’s book of convention. Rowlandson may well have been similarly critical. British travellers to eighteenth-century Paris noted (and often bemoaned) a propensity to smile as a national characteristic of the French. And indeed, examined closely, the woman in the ultimate stage of Rowlandson’s transformation scene bears a more than passing ressemblance to the Vigée Le Brun painting. Smile, teeth, tilt of the head, big hair, vaguely oriental headgear, graciously-draped left forearm – all suggests a deliberate satire of a notorious image.

But there is a French influence here too which has escaped detection. Rowlandson was a regular visitor to Paris. On his most recent prior visit there in 1787, he is likely to have seen the ‘Self-Portrait’ that Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun displayed at the Louvre that year. The smiling portrait shocked connoisseurs within French high society and created quite a stir. Portraying a respectable woman opening her mouth to smile while revealing white teeth broke every rule in Western art’s book of convention. Rowlandson may well have been similarly critical. British travellers to eighteenth-century Paris noted (and often bemoaned) a propensity to smile as a national characteristic of the French. And indeed, examined closely, the woman in the ultimate stage of Rowlandson’s transformation scene bears a more than passing ressemblance to the Vigée Le Brun painting. Smile, teeth, tilt of the head, big hair, vaguely oriental headgear, graciously-draped left forearm – all suggests a deliberate satire of a notorious image.

One wonders too whether in his stay in Paris in 1787, Rowlandson also got to hear of the experiments being undertaken by Nicolas Dubois de Chémant to create the world’s first porcelain dentures? Marketed from 1788, they crossed the Channel, and by 1792, when Rowlandson composed his print, were on sale in London, from Dubois’s Soho outlet. Were the denture-set that ‘Miss Archer’ was inserting into her aristocratic mouth one of Dubois de Chémant’s finest? Beneath the anti-aristocratic and gendered politics of the image – produced just as France were embarking on the revolutionary Wars – there lurks a Francophobia that was a distinguishing feature of the Golden Age of British Caricature.

Colin Jones is Professor of History at Queen Mary University of London. His latest book, The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris, was published by Oxford University Press.

Colin Jones is Professor of History at Queen Mary University of London. His latest book, The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris, was published by Oxford University Press.

W&M is excited to have three (3) signed copies of The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on March 30th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaway

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

March Books

Charles Spencer “Killers of the King: The Men who Dared to Execute Charles I”

James McGrath Morris, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne the First Lady of the Black Press”

Colin Jones, “The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris

March 16, 2015

Travel, Letters, and Old Road Maps

by Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

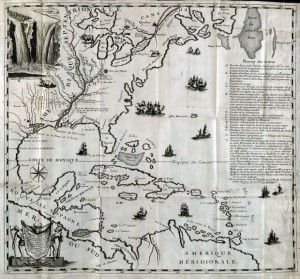

Maps have always captivated the imagination as well as providing guidance for travelers. Early explorers sent home maps of their ‘discoveries’ and these were widely circulated in printed atlases and pamphlets. Even armchair travelers could imagine themselves sharing the adventures that they read about in travel accounts, a form of literature that by the eighteenth century had become more popular than novels.

Maps have always captivated the imagination as well as providing guidance for travelers. Early explorers sent home maps of their ‘discoveries’ and these were widely circulated in printed atlases and pamphlets. Even armchair travelers could imagine themselves sharing the adventures that they read about in travel accounts, a form of literature that by the eighteenth century had become more popular than novels.

By the end of the seventeenth century, even unambitious travelers could plan a road trip. With the introduction of centralized postal systems in France and England, new roads were built linking the postal stops and these roads began to be policed by government agents. For the first time travelers could ride in coaches as paying passengers, using the scheduled stops to plan their itinerary.

These improvements in infrastructure led to more road trips for people who would have been more hesitant to travel before the age of the postal routes. Anyone could move about independently and even anonymously, using a public coach. Women no longer felt obliged to disguise themselves in men’s clothes or learn to ride a horse or obtain an  escort in order to travel in safety. Almost as important as the availability of road maps for planning a trip, was the fact that these maps began to include symbols that indicating possible resting places. Finding a safe place to stay overnight could be a challenge. Early road maps indicate the location of monasteries and convents, which often functioned as hotels. The maps were decorated with images showing enticing views of cities that the traveler would pass through.

escort in order to travel in safety. Almost as important as the availability of road maps for planning a trip, was the fact that these maps began to include symbols that indicating possible resting places. Finding a safe place to stay overnight could be a challenge. Early road maps indicate the location of monasteries and convents, which often functioned as hotels. The maps were decorated with images showing enticing views of cities that the traveler would pass through.

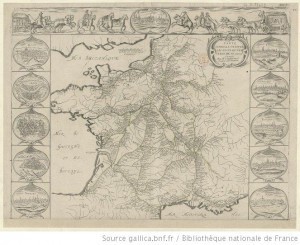

Maps helped those who were left behind, too. Having a map meant you could follow the route of a loved one, and feel closer to them as they moved away from you or track them as they made their way home. Madame de Sévigné kept in close contact with her beloved daughter by letter following the young woman’s move from Paris to Provence with her new husband. Her mother was thrilled to obtain a road map of France after her daughter’s departure in February 1671.

“I am still with you,” she wrote. “I see that carriage still moving, and nevermore approaching me. I am on the road and I am sometimes afraid that it will overturn; the recent rains put me in despair and the Rhone gives me a strange fear. I have a map in front of me; I know all the places where you will be staying, tonight you are in Nevers, on Sunday you will be in Lyon, where you will receive this letter.”

“I am still with you,” she wrote. “I see that carriage still moving, and nevermore approaching me. I am on the road and I am sometimes afraid that it will overturn; the recent rains put me in despair and the Rhone gives me a strange fear. I have a map in front of me; I know all the places where you will be staying, tonight you are in Nevers, on Sunday you will be in Lyon, where you will receive this letter.”

Despite the sad memory of her daughter’s departing carriage and her anxiety at being able to visualize the dangers of the route, she is relieved to be able to picture the whole voyage, and delighted by a reliable postal system.

March 14, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Women in History

By April Stevens (W&M Editorial Assistant)

Traditionally known as the “finer sex”, this week we are looking at the real role strong women have played in history. In honor of International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month we are highlighting women from all walks of life who flouted convention, and took charge of their own history.

Taking Control of the World’s Oldest Profession

Prostitution is typically (and rightfully) considered an exploitation of women, but in “History’s 10 Most Famous Brothel Madams” Ash Richter shows another side to the world’s oldest profession. This article highlights Madams who took control of their own financial freedom by running some of the world’s most infamous houses of ill-repute. Learn about these “entrepreneurs” like Elizabeth Needleman who ran London’s famous Park Place house and was immortalized by Alexander Pope’s poems and William Hogarth’s drawings (pictured here).

Do you want to know more about some of the “less well-known awesome females” in English history? Take a look at the first part of Sam Kinchin-Smith’s series on inspirational women from history who “made it happen”. To whet your appetite, consider Blanche Arundell who refused to surrender Old Wardour Castle to the roundheads, and held off 1300 soldiers with a handful of men and women from her household.

Perhaps you prefer to learn about “The 6 Most Badass Women in History You’ve Never Heard of Before”, though with the savvy readers we have at Wonders & Marvels, you may be reacquainting yourself with old friends. Ever heard of Nana Ama’u? Learn more about this 18th century Nigerian advocate for educating women in the article.

Beyond the Amazons: Warrior Women

As St. Patrick’s Day approaches, we pay tribute to the Ireland’s women warriors and feminists, both mythical and real. Read about figures like the legendary Gráinne, a clan chief, alleged pirate, and Irish rebel leader.

Clamoring for more? Check out some of our recent posts featuring inspiring women:

Lives of the Obscure: The Letters of a Cockney Match Factory Girl

Finding Freedom in Paris: African American Women in the Jazz-Age

Don’t forget to sign up for this month’s book giveaways, some of which also feature fascinating women.

Monthly Book Giveaway

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

March Books:

Charles Spencer “Killers of the King: The Men who Dared to Execute Charles I”

James McGrath Morris, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne the First Lady of the Black Press”

Colin Jones, “The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris

March 12, 2015

Juana of Castile’s Baggage

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (Former Regular Contributor)

Imagine being known to history as Juana “la Loca” or Juana “the crazy one.” That is heavy baggage to carry forward from the sixteenth century into the postmodern era. Before she was Juana la Loca, she was Juana of Castile (1479-1555), the eldest surviving heir of the famous monarchs Isabel of Castile (r. 1474-1504) and Fernando of Aragon (r. 1474-1516). When her mother died in 1504, earlier marriage capitulations made it impossible for her father to inherit the throne, making Juana the rightful sovereign of Castile.

Yet her ambitious father and her husband, Philip the Fair (1478-1506), sought to break this neat line of succession and push her off the political stage. In part, they used rumors of her instability to discredit her authority. When Philip died unexpectedly in the city of Burgos in 1506, Juana’s behavior unfortunately fueled the flames of her detractors. She insisted upon accompanying her husband’s funeral cortege across the Iberian peninsula from Burgos to his final resting place in Granada. Fernando presented this act of wifely devotion and other emotional outbursts as evidence of mental illness and advanced his own claims to the throne. He eventually forced her seclusion in a convent in the small town of Tordesillas.

Yet her ambitious father and her husband, Philip the Fair (1478-1506), sought to break this neat line of succession and push her off the political stage. In part, they used rumors of her instability to discredit her authority. When Philip died unexpectedly in the city of Burgos in 1506, Juana’s behavior unfortunately fueled the flames of her detractors. She insisted upon accompanying her husband’s funeral cortege across the Iberian peninsula from Burgos to his final resting place in Granada. Fernando presented this act of wifely devotion and other emotional outbursts as evidence of mental illness and advanced his own claims to the throne. He eventually forced her seclusion in a convent in the small town of Tordesillas.

Fernando died in 1516, leaving behind Juana and her son, Charles I (1500-1558), as his heirs. Despite her confinement, Charles continued to consult with her and maintained the pretense of joint rule with his mother. A group of urban leaders who were dissatisfied with Charles’ long absences from Castile and reliance on foreign advisers even appealed to Juana during a revolt they staged in 1520-21. Some clearly believed she could still exercise independent sovereign power.

But in the end, later generations would immortalize her for her presumed, but never proven, insanity. Juana’s plight captured the attention of nineteenth century Romanticists, for example, who sentimentalized her devotion to Philip in paintings like this one above by Francisco de Pradilla, produced in 1877. This haunting portrait speaks volumes about history’s distorted image of a misunderstood queen. In 2001 a Spanish movie, “Juana la Loca,” (translated for English-speaking audiences as “Mad Love”) perpetuated this interpretation of Juana’s instability.

Recent scholarship has sought to investigate the true character of Juana’s personality and exercise of political authority (see, for example, Bethany Aram, Juana the Mad: Sovereignty and Dynasty in Renaissance Europe, 2005). It reveals that she often rejected the power that she was entitled to, but she was not insane. At some moments she worked vigorously to assert her sovereignty and her control over her royal household. Only time will tell if interpretations like this are enough to rid Juana of the weighty baggage of being portrayed as a mentally unstable queen.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

March 9, 2015

Going Over the Edge: The Allure of Nature

by Helen King

I’m currently visiting Oregon, and my host took me to see the huge waterfalls at Silver Falls State Park. I’ve seen Niagara Falls, and while the Oregon ones are clearly not in that league, they are very beautiful, not least because of their temperate rainforest setting.

But why do I find them ‘beautiful’? As I bent down to pass under the overhanging rock – lava, from the volcanic past of this region – I was also aware of the risk of rock falls, of slipping and falling into the cold water underneath tons of water gushing down with enormous force. When does something in wild nature become attractive rather than terrifying?

This is a historical question. Wild nature has not always been beautiful. It has been argued that the ancient Roman interest in killing wild animals in the arena was all about showing their control over nature. Nature was there to be defeated, or to be managed, but not to be enjoyed. The controlled wilderness of the eighteenth-century park shows further how the environment can be tamed, domesticated. It was the Romantic movement, strongest in the first half of the nineteenth century, which led us to see nature in a different way. The range of emotions conjured up by confronting nature – including fear and awe – were presented as an alternative to reason as a way of understanding the world. And just what counted as acceptable parts of nature also shifted.

The perfect example is the Grand Canyon. I’m lucky enough to have been there too, but it was not on my ‘bucket list’ at all – and it was so much more impressive than I could have expected, not least because of the weird sensation of one part of my mind saying ‘this is real, it’s 3D’ while another part was refusing to compute that, and kept making me see it as a painted 2D back-cloth.

But it was only in the late nineteenth century that the Canyon came to be seen as a ‘wonder’. Before that, it was a gap, rather than a view, a wound in the earth, an obstacle rather than a destination, a threat not an adventure. Due to going down rather than up, it was not even obvious to European explorers that there was anything there, until they were very close to it. In the mid-nineteenth century it was mapped by the government. When J.C. Ives explored it in 1857 he announced that it would remain an unvisited and ‘profitless locality’. It finally became a national monument only in 1908. Officially announcing it as such, President Roosevelt called it ‘this great wonder of nature’ and spoke of its ‘grandeur, sublimity and loveliness’.

The shift in perception of the Canyon was helped by art. The artist Thomas Moran and the photographer William Henry Jackson did much to bring the Canyon to people’s attention. Moran had already painted the Yellowstone Canyon, and in 1874 produced a companion piece, ‘The Chasm of the Colorado’. Like his Yellowstone painting, it was sold to Congress. The coming of the railway made the site more accessible, and other artists came to paint it. The director of the Santa Fe Railroad company gave them a free trip, in return for their paintings which were then reproduced on calendars so that the fame of the site spread. The canyon was attractive to artists partly because it represented such a challenge – was it even possible to capture it in a painting? It was attractive to business as a marketing opportunity.

Like his Yellowstone painting, it was sold to Congress. The coming of the railway made the site more accessible, and other artists came to paint it. The director of the Santa Fe Railroad company gave them a free trip, in return for their paintings which were then reproduced on calendars so that the fame of the site spread. The canyon was attractive to artists partly because it represented such a challenge – was it even possible to capture it in a painting? It was attractive to business as a marketing opportunity.

The challenge of these extreme sites has also led to a range of individual attempts to ‘conquer’ them. At Niagara Falls the performances of people such as Charles Blondin, in the second half of the nineteenth century, included a range of stunts while crossing it on a tightrope. A nd even the relatively ‘mild’ Silver Falls had their own performer, ‘Daredevil Al’ Faussett, who in 1928 went over one of the waterfalls in a canoe, with a cable rigged up to guide the canoe into the rather small area of water at the bottom of the falls. The cable malfunctioned but somehow Al survived. The exhibition at the Falls includes a film of him going over the edge, and ends with him sitting up in bed in the hospital, drinking a cup of tea and looking somewhat manic. Maybe nature is bad for one’s health!

nd even the relatively ‘mild’ Silver Falls had their own performer, ‘Daredevil Al’ Faussett, who in 1928 went over one of the waterfalls in a canoe, with a cable rigged up to guide the canoe into the rather small area of water at the bottom of the falls. The cable malfunctioned but somehow Al survived. The exhibition at the Falls includes a film of him going over the edge, and ends with him sitting up in bed in the hospital, drinking a cup of tea and looking somewhat manic. Maybe nature is bad for one’s health!

Do you feel the urge to conquer nature? Do you like to explore it, or stay away from it, and do you find it dangerous, or beautiful, or both?

Going over the edge: the allure of Nature

by Helen King

I’m currently visiting Oregon, and my host took me to see the huge waterfalls at Silver Falls State Park. I’ve seen Niagara Falls, and while the Oregon ones are clearly not in that league, they are very beautiful, not least because of their temperate rainforest setting.

But why do I find them ‘beautiful’? As I bent down to pass under the overhanging rock – lava, from the volcanic past of this region – I was also aware of the risk of rock falls, of slipping and falling into the cold water underneath tons of water gushing down with enormous force. When does something in wild nature become attractive rather than terrifying?

This is a historical question. Wild nature has not always been beautiful. It has been argued that the ancient Roman interest in killing wild animals in the arena was all about showing their control over nature. Nature was there to be defeated, or to be managed, but not to be enjoyed. The controlled wilderness of the eighteenth-century park shows further how the environment can be tamed, domesticated. It was the Romantic movement, strongest in the first half of the nineteenth century, which led us to see nature in a different way. The range of emotions conjured up by confronting nature – including fear and awe – were presented as an alternative to reason as a way of understanding the world. And just what counted as acceptable parts of nature also shifted.

The perfect example is the Grand Canyon. I’m lucky enough to have been there too, but it was not on my ‘bucket list’ at all – and it was so much more impressive than I could have expected, not least because of the weird sensation of one part of my mind saying ‘this is real, it’s 3D’ while another part was refusing to compute that, and kept making me see it as a painted 2D back-cloth.

But it was only in the late nineteenth century that the Canyon came to be seen as a ‘wonder’. Before that, it was a gap, rather than a view, a wound in the earth, an obstacle rather than a destination, a threat not an adventure. Due to going down rather than up, it was not even obvious to European explorers that there was anything there, until they were very close to it. In the mid-nineteenth century it was mapped by the government. When J.C. Ives explored it in 1857 he announced that it would remain an unvisited and ‘profitless locality’. It finally became a national monument only in 1908. Officially announcing it as such, President Roosevelt called it ‘this great wonder of nature’ and spoke of its ‘grandeur, sublimity and loveliness’.

The shift in perception of the Canyon was helped by art. The artist Thomas Moran and the photographer William Henry Jackson did much to bring the Canyon to people’s attention. Moran had already painted the Yellowstone Canyon, and in 1874 produced a companion piece, ‘The Chasm of the Colorado’. Like his Yellowstone painting, it was sold to Congress. The coming of the railway made the site more accessible, and other artists came to paint it. The director of the Santa Fe Railroad company gave them a free trip, in return for their paintings which were then reproduced on calendars so that the fame of the site spread. The canyon was attractive to artists partly because it represented such a challenge – was it even possible to capture it in a painting? It was attractive to business as a marketing opportunity.

Like his Yellowstone painting, it was sold to Congress. The coming of the railway made the site more accessible, and other artists came to paint it. The director of the Santa Fe Railroad company gave them a free trip, in return for their paintings which were then reproduced on calendars so that the fame of the site spread. The canyon was attractive to artists partly because it represented such a challenge – was it even possible to capture it in a painting? It was attractive to business as a marketing opportunity.

The challenge of these extreme sites has also led to a range of individual attempts to ‘conquer’ them. At Niagara Falls the performances of people such as Charles Blondin, in the second half of the nineteenth century, included a range of stunts while crossing it on a tightrope. A nd even the relatively ‘mild’ Silver Falls had their own performer, ‘Daredevil Al’ Faussett, who in 1928 went over one of the waterfalls in a canoe, with a cable rigged up to guide the canoe into the rather small area of water at the bottom of the falls. The cable malfunctioned but somehow Al survived. The exhibition at the Falls includes a film of him going over the edge, and ends with him sitting up in bed in the hospital, drinking a cup of tea and looking somewhat manic. Maybe nature is bad for one’s health!

nd even the relatively ‘mild’ Silver Falls had their own performer, ‘Daredevil Al’ Faussett, who in 1928 went over one of the waterfalls in a canoe, with a cable rigged up to guide the canoe into the rather small area of water at the bottom of the falls. The cable malfunctioned but somehow Al survived. The exhibition at the Falls includes a film of him going over the edge, and ends with him sitting up in bed in the hospital, drinking a cup of tea and looking somewhat manic. Maybe nature is bad for one’s health!

Do you feel the urge to conquer nature? Do you like to explore it, or stay away from it, and do you find it dangerous, or beautiful, or both?

March 8, 2015

How I Write History…with Paul Strohm

An Interview with Paul Strohm (Guest Contributor)

An Interview with Paul Strohm (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: Your latest book Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury tackles a very well known historical figure and literary work. What are the challenges and benefits on writing about such a famous topic?

Paul Strohm: As for benefits, you get a certain uptake with a known figure. This is especially true in the UK, where there’s a more established audience for historical biography and related subjects. (My book has been reviewed by most major newspapers and relevant periodicals in the UK, though it has had much less consistent coverage in the US.) The challenge of writing about a well-known figure is, of course, to have your own purpose and rationale. A couple of good “whole life” biographies are already out there, and part of my idea was to write about a particular, defining episode in Chaucer’s life. My American publisher has aptly called it a “microbiography.” This has meant that I’ve been able to work from the historical records and “life records” in a detailed way, and I think I’ve come up with some interesting and rather revisionary conclusions.

W&M: Chaucer’s Tale is your first attempt at biography, or, as you say, “microbiography.” Did you approach the writing of biography any differently than your other historical works?

Paul Strohm: Writing a life-narrative took me in an entirely new and somewhat unexpected direction. Narrative itself, and the construction of narrative, forces you to make decisions. You can’t endlessly say, was it this way or was it that way: Was Chaucer thrown out of his Aldgate apartment or did he leave as a matter of personal choice? Was he pushed out of his job in Customs or did he jump? My previous, more academic, writing allowed me to hesitate over such questions, or even to build a certain indecision into subject-matter of what I was writing. Whereas biographical writing–a kind of story-telling, actually–demands that you choose, and these choices are cumulative and irreversible. The act of narration itself can be a powerful discovery-procedure, can lead to insights you wouldn’t otherwise have had. But, compared with more supple kinds of analysis, it can lead you in directions you didn’t quite forsee or didn’t quite want to choose.

Paul’s frequent research home.

W&M: You have had a long and successful career as an academic and a writer. Have technological advancements changed your research and writing process? If so, how?

Paul Strohm: I’ve done lots of journalism, so I started out composing on a typewriter and the switch to a computer keyboard was an easy one for me. But it’s a fringe benefit that I want to hail: the chance to cut-and-paste. In my view, good writing is advanced by bold revision: not just tinkering with a word or two, but really reshaping and moving things around. And cut-and-paste facilitates revision without all that retyping, and I’m endlessly grateful for it. Some labor-saving stuff leaves me cold, though. All that internet searching and kindred mechanisms. I went into this because I like the labor: going to the library, looking things up, doing my own indexing, things like that. I’m not interested in finding myself estranged or alienated from the hands-on aspects of what a writer-researcher does.

W&M: Over the span of your writing career, what is one thing that you have learned about writing history that you feel is particularly important for new writers to know?

Paul Strohm: I’ve become more and more sensitive to what might be called the “multiplicity of time,” the sense in which historical time doesn’t just march along but proceeds unevenly so that different temporalities potentially co-exist. Each of us lives not only in the present moment, but also with fragments of unresolved past and intimations of uncertain future. This sense–that no moment in time is ever wholly unitary or present to itself, but rather inherently fractured and inconsistent–has a kind of “post-modern” edge to it, but it is actually quite venerable. No view of the subject has ever influenced me so much as Augustine’s meditation on time in Book 11 of his Confessions. But this is a view that you don’t just “adopt,” that each person has to rediscover, to work out for himself or herself.

Paul Strohm is Garbedian Professor of the Humanities, Emeritus, at Columbia University. His Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury was published November 2014 by Viking Press.

Paul Strohm is Garbedian Professor of the Humanities, Emeritus, at Columbia University. His Chaucer’s Tale: 1386 and the Road to Canterbury was published November 2014 by Viking Press.

March 5, 2015

The Scientist Pope

By Nancy Marie Brown (Guest Contributor)

Sylvester II, pope from 999 to 1003, was a wizard. He had sold his soul to the devil.

Sylvester II, pope from 999 to 1003, was a wizard. He had sold his soul to the devil.

So, at any rate, said the official Lives of the Popes written in the late 1200s by Martin the Pole, a Dominican friar, and referenced for hundreds of years.

Friar Martin wasn’t making this up. He had good sources.

Pope Sylvester was “the best necromancer in France, whom the demons of the air readily obeyed in all that he required of them by day and night,” wrote Michael the Scot earlier that century.

In the 1120s, William of Malmesbury claimed Pope Sylvester spent his time in Rome practicing “the black arts.” He owned a “forbidden” book stolen from a Saracen philosopher. After “close inspection of the heavenly bodies,” he made himself a talking statue that would answer any yes-or-no question.

Then in 1602, the papal librarian Cardinal Baronius came across a collection of Pope Sylvester’s letters and concluded he “was nothing but a learned man who was ahead of his time. Those who want to efface his name from the catalogue of popes are ignorant fools.”

What did the cardinal read in those letters? About Pope Sylvester II’s abacus, or counting board.

Pope Sylvester II was the first Christian known to teach math using the nine Arabic numerals and zero, as a 10th-century manuscript found in 2001 reveals. His abacus introduced the place-value system of arithmetic and mimics the algorithms we use today for adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing. It has been called the first counting device in Europe to function digitally – even the first computer. In a chronology of computer history, Gerbert’s abacus is one of only four innovations mentioned between 3000 B.C. and the invention of the slide rule in 1622.

Pope Sylvester II wasn’t a wizard. He was a geek.

Nancy Marie Brown writes about science, history, and sagas. She is the author, most recently, of The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages (2010). Her previous books include The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman and Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist Looks at Genetically Modified Food, which was named one of the Best Sci-Tech Books for General Readers for 2004 by Library Journal.

Nancy Marie Brown writes about science, history, and sagas. She is the author, most recently, of The Abacus and the Cross: The Story of the Pope Who Brought the Light of Science to the Dark Ages (2010). Her previous books include The Far Traveler: Voyages of a Viking Woman and Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist Looks at Genetically Modified Food, which was named one of the Best Sci-Tech Books for General Readers for 2004 by Library Journal.

This post was originally featured on Wonders & Marvels in 2012.