Holly Tucker's Blog, page 35

April 8, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xvi

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Were you aware that yesterday, April 7th, was National Beer Day? Neither was I. This day devoted to brewskis got me thinking that there must be quite an interesting history surrounding beer in America, and across the globe. Not a fan of the “amber nectar”? Don’t worry this special edition of Cabinet of Curiosities is devoted to all forms of addictive and mood-altering libations.

How about a Cold One?

It is no wonder that Americans have a day devoted to beer when we consider the age of this brew. We often think of ancient societies drinking wine, but a recent archaeological dig in Tel Aviv uncovered an Ancient Egyptian Brewery dating back to the Bronze Age.

It is no wonder that Americans have a day devoted to beer when we consider the age of this brew. We often think of ancient societies drinking wine, but a recent archaeological dig in Tel Aviv uncovered an Ancient Egyptian Brewery dating back to the Bronze Age.

Since the Bronze Age, beer has certainly earned its place in modern culture. If you want to know more, you may want to take a look at Mark Hailwood’s new study on Alehouses and Good Fellowship in Early Modern England. Hailwood shows how the alehouse became a central social gathering place from 1550-1700.

Clearly, beer has proved popular across the ages, but what affect has this had on modern man? Medical Daily takes a look at the history of beer’s role in human health. The article traces beer from Ancient China, through the Middle Ages and prohibition to see how it affects us today.

Red or White?

For those of you who prefer to sip your alcohol from a stemmed glass, let us consider the history of the grape. Tom Oder’s article “How Grapes Changes the World” traces the history of wine and its impact on society, culture, and even religion.

For those of you who prefer to sip your alcohol from a stemmed glass, let us consider the history of the grape. Tom Oder’s article “How Grapes Changes the World” traces the history of wine and its impact on society, culture, and even religion.

Thirsting for more (pun intended) about how your favorite Bordeaux or Chardonnay was developed? Peruse VinePair’s illustrated timeline “How Wine Colonized the World” for fascinating images and facts about how wine conquered our palates and our cultures.

A Different Kind of Buzz

In the modern landscape of pumpkin-spice lattés and frappuccinos are Americans becoming more obsessed with their caffeine fix than alcoholic beverages? The decision is yours, but perhaps Thor Hanson’s recent article will sway you one way or the other. Hanson investigates the addictive nature of coffee and caffeine, from its origins in the 18th Caribbean to today.

These days we may be tempted to think that the alehouse has been replaced by the coffeehouse as social watering hole. Yet, coffeehouses have been culturally important institutions since their inception in European cities like Paris and Vienna. A recent short documentary by Orlando Gili explores the enduring appeal of the Vienna coffeehouses that are still an integral part of the city’s history.

These days we may be tempted to think that the alehouse has been replaced by the coffeehouse as social watering hole. Yet, coffeehouses have been culturally important institutions since their inception in European cities like Paris and Vienna. A recent short documentary by Orlando Gili explores the enduring appeal of the Vienna coffeehouses that are still an integral part of the city’s history.

For our friends “across the pond” we cannot forget that other caffeinated beverage, one so important to both Eastern and Western society that it sparked a revolution: Tea. NPR’s latest Tea Tuesday focuses on how tea and sugar shaped the British Empire. Take a look at this article and its lovely images, to see how tea and sugar shaped the global economy, and history as we know it.

Now that we have quenched your thirst about all sorts of elixirs, you may be getting hungry! Take a look at some of our recent posts on food and drink right here on Wonders & Marvels:

Work Should Be More Like a Café

Do you like to read? Do you like to read FREE books? Then, please enter our monthly book giveaway!

April 7, 2015

The Transfiguration of James Madison

By Thomas Fleming (Guest Contributor)

The most important years of short, slight James Madison’s life began in 1785 when he joined a worried ex-General George Washington on his sunny piazza at Mount Vernon, overlooking the broad Potomac River. Ex-Continental Congressman Madison was there to discuss how to create a stronger federal government. Soon there was a Constitutional Convention, then a fierce contest to ratify the results, followed by the election of Washington to a powerful new office, the presidency.

In all these dramas, these two very different men were amazingly effective partners. A recent insightful biographer has described Washington as a realistic visionary. Madison was the brilliant structural engineer who turned his vision into a working government. As two men grew closer, Washington began signing his letters to Madison with a rare (for him) word: “Affectionately.”

In all these dramas, these two very different men were amazingly effective partners. A recent insightful biographer has described Washington as a realistic visionary. Madison was the brilliant structural engineer who turned his vision into a working government. As two men grew closer, Washington began signing his letters to Madison with a rare (for him) word: “Affectionately.”

But another Virginian was soon competing for the ex-Congressman’s affections. When Thomas Jefferson had been governor of wartime Virginia (1779-81), Madison had been his favorite advisor. During the creative years of Madison’s partnership with Washington, Jefferson had been in France, serving as America’s ambassador. When he became Washington’s Secretary of State in 1790, it soon became apparent that the late arrival had a low opinion of the Constitution and the presidency. He saw no need for such a strong federal government. He was soon disapproving and dismissing almost everything the president was doing — and he turned Madison, by this time a prominent Congressman, into an almost shameless disciple.

Soon Madison was telling Congress that Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton’s brainchild, the Bank of the United States was dangerously similar to the Bank of England – proof that it was part of a Hamilton plot to create an American king. The Congressman joined Jefferson in lavishing praise on the French Revolution, even when radicals began massacring thousands of innocent people.

Madison helped found a newspaper that relentlessly attacked Hamilton — and President Washington. Madison wrote for the paper under various pseudonyms, denouncing the commercial republic Hamilton was creating, with Washington’s enthusiastic approval. Instead the Congressman was a fervent apostle of Jefferson’s vision of America as a nation of virtuous farmers.

Not without regret – Martha Washington was very fond of Madison’s wife, Dolley – the President stopped speaking to his former partner. The hostile feeling was reciprocated. When Washington died unexpectedly in 1799, Madison joined Jefferson in declining to attend his memorial service in the nation’s capital, Philadelphia.

With crucial help from Madison, Jefferson became president in 1801 and appointed his favorite supporter secretary of state. Madison became an even more devoted disciple. He made no objection when Jefferson did his best to make Washington’s presidency insignificant. He helped Jefferson create the illusion that Congress was all powerful and the president an agreeable supernumerary who merely made helpful suggestions. Madison’s reward was the 1808 nomination for president in his own right.

Madison soon discovered some of the problems a Jeffersonian style presidency could create if you were not a tall Virginian who had written the Declaration of Independence. Congress’s attitude toward “Little Jemmy,” as they called him was a barely concealed contempt. The congressman thought they were in charge of the country and acted that way. When the Bank of the United States tried to renew its charter in 1810, Congress repudiated it. Madison did not say a word in its defense.

With 99 percent of the British army fighting for survival against Napoleon in Europe, Congress thought Canada would be an easy conquest. In Monticello, ex-president Jefferson assured everyone that it would be “just a matter of marching.” Thus the War of 1812 began. President Madison’s army consisted of a few regulars and thousands of untrained militia. Jefferson assured everyone there was no need for regulars if these amateur patriots were properly led.

The war became a series of disasters. The handful of British regulars in Canada repeatedly routed Madison’s Jeffersonian army. Without the Bank of the United States, Madison discovered his government did not have enough cash to pay the salaries of their clerks. The climax was an invasion of Washington DC by some 4,500 redcoats, who torched every major building, including the White House. The air grew thick with calls for Little Jemmy’s impeachment. From Europe came news of Napoleon’s collapse, leaving the United States alone against Britain’s gigantic navy and veteran army. At Monticello ex-President Jefferson fell strangely silent.

Fortunately, a few Americans kept their heads. One was a general named Andrew Jackson. The other was a commodore named Thomas Macdonagh who commanded a fleet on Lake Champlain. A third was a diplomat named John Quincy Adams. Jackson smashed a key British ally, the Creek Indians, and did likewise to an army of British veterans in a battle for control of New Orleans and the Mississippi River. Macdonagh routed a British fleet escorting an army descending from Canada. In Europe, Adams’s canny combination of defiance and persuasion talked the British into a more than passable peace treaty, which President Madison instantly signed.

Madison found himself still president with a year of peacetime governing left in his term. He decided he should tell the American people what he had learned from his recent experiences. He began by repudiating a Jefferson-style war. He informed Congress that it was time for them to realize that “skill in the use of arms and the essential rules of discipline” – in short, a well-trained regular army – was crucial to the nation’s survival. Next he chartered a new Bank of the United States — and said it should be modeled on The Bank of England. Next President Madison called for tariffs to protect American industries, a move that signaled he was embracing the Hamilton/Washington idea of a commercial republic rather than the farming nation Jefferson envisioned.

Out of office, Madison managed to stay friendly with Jefferson and assist him in founding the University of Virginia. When Jefferson asked him to help put together a list of primary documents the students should read, Madison suggested George Washington’s Farewell Address, the landmark message he had published when he left the presidency. Madison knew, of course, that this document was not only rich in advice to the nation about the importance of the union and the danger of favoring a foreign nation above one’s native land. It was also a not very veiled attack on Thomas Jefferson. Madison was relieved to discover Jefferson had no objections. By this time he was ready to admit that the judgment of his former disciple was often superior to his own.

After Jefferson’s death in 1826, some politicians began arguing that a separation of the North and South was the answer to frequent sectional acrimony in Congress. They cited Jefferson’s claim that there was nothing wrong with “scission” – secession – to protect the basic rights of a state’s citizens from a too powerful federal government. The idea became wildly popular in South Carolina.

Madison was appalled. At first he tried to deny Jefferson ever made such a claim. But the would-be rebels were able to flourish those explosive words in Jefferson’s handwriting. Madison tried to tell the secessionists that Jefferson never meant such a step to be taken except as a last desperate extreme. The ex-president’s words were dismissed as the mumblings of an old man. A grim Madison advised President Andrew Jackson to end the crisis with the threat of an armed invasion of South Carolina. He did so and the rebels collapsed.

A deeply troubled Madison decided to leave his own version of a farewell address. In a statement called “Advice to My Country” he summed up his thinking in words that George Washington might have written.

The advice nearest my heart and deepest in my conviction is, that the Union of the United States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened, and the disguised one as a Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise.

That profound warning marked the final transformation of James Madison. He had abandoned the divisive ideology that emanated from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and returned to the sunny porch of Mount Vernon as a partner of that realistic visionary, George Washington. It is a journey that every man and woman in America can and should take –now and in the future.

Adapted from The Great Divide: The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation by Thomas Fleming (Da Capo Press).

Thomas Fleming, a frequent guest on PBS, C-SPAN, and the History Channel, has written more than forty widely praised books on America’s past, including A Disease in the Public Mind. His new book, from which this piece is adapted, is The Great Divide: The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation. He lives in New York City.

Thomas Fleming, a frequent guest on PBS, C-SPAN, and the History Channel, has written more than forty widely praised books on America’s past, including A Disease in the Public Mind. His new book, from which this piece is adapted, is The Great Divide: The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation. He lives in New York City.

W&M is excited to have two (2) copies of The Great Divide this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on April 30th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

April Book Giveaways

Thomas Fleming, The Great Divide:The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation

Douglas Boin, “Coming out Christian in the Roman World”

Joan Dejean, “How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City”

April 6, 2015

Arab Warrior Queens

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Neo-Assyrian records of the eighth century BC name several queens who ruled Qedar, a confederation of nomadic Arab and Semitic tribes that ranged from the Syrian desert to the Nile. The Qedarites were also mentioned in the Old Testament and by Greek and Roman writers.

Neo-Assyrian records of the eighth century BC name several queens who ruled Qedar, a confederation of nomadic Arab and Semitic tribes that ranged from the Syrian desert to the Nile. The Qedarites were also mentioned in the Old Testament and by Greek and Roman writers.

Zabibi (her name means “raisin”) was “Sarrat qur Aribi” (Queen of the Arabs”) from 738-733 BC. Some have suggested that she was part of a dynasty of female rulers that included the Queen of Sheba, the mysterious queen who met King Solomon in the Old Testament. Zabibi ruled as a vassal who paid tribute to the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser III. Her successor was Samsi (Arabic, “sun”).

Queen Samsi made an alliance with Rakhianu, ruler of Damascus, and together they led a rebellion against Tiglath Pileser III in 732 BC. Arabian warriors, male and female rode horses and used bows and javelins. The decisive battle took place on the plain below Mount Sa-qu-ur-ri (site unknown) and Samsi’s army was defeated. According to Assyrian archives, Queen Samsi “fled into the desert like a wild she-ass.”

The Assyrian comparison was apt. The Syrian hemippe, an extinct species of small (about 3 feet at the shoulder) but very strong and swift onager that was once common in herds across the nomad territories of Syria, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Iran. The Syrian onagers were dark and tawny in summer and pale sand-colored in winter. Considered as beautiful as thoroughbred horses the asses were notoriously elusive and impossible to tame or domesticate. The last two wild Syrian onagers both died in 1927: one was shot in Jordan and the other died a captive in a zoo in Vienna.

Samsi surrendered and negotiated an agreement with Tiglath Pileser that allowed her to remain queen of the Qedar until 728 BC. She was succeeded by Queen Yatie.

Yatie joined the coalition of Chaldeans, Elamites, and Aramaeans to fight the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 703 BC for control of Babylon. Her successor was Te’el-hunu. Nothing is known of her except her name. The Qedarites also disappear from the historical record by the first century AD.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

April 2, 2015

Hobgoblin Classification in the Eighteenth Century

By Lisa Smith (Regular Contributor)

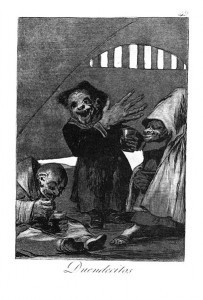

Goya, Duendicitos (elves), Los Caprichos, 1799.

The modern goblin might be mean and ugly, but early modern goblins were a different breed: helpful, if mischievous, creatures. The shift began in the eighteenth century when goblins went extinct.

Augustin Calmet, a Benedictine monk, included two chapters on goblins in his Dissertation (1746), where he provided evidence of goblins from “unexceptionable witnesses”.[1] Typical goblin behaviour included looking after horses, helping in the house, or working in the mines. John Brand (1777) also noted goblins’ helpfulness, “provided they were civilly used”.[2]

Goblins could be naughty. Pliny the Younger, Calmet tells us, had a household goblin. A freed man, who slept with a younger brother, dreamed once that someone was cutting his hair. On waking, the freed man discovered that his hair had been cut and scattered around the room. A few nights later, a young boy in the household—who slept in a room with several others—had the same thing happen.

Some goblin tricks were troubling. In one 1745 case, a French soldier stationed in Flanders complained three times to his captain, Count Despillers, about being unable to sleep. Despillers only took him seriously when the soldier, “no fool” and known for bravery, threatened to desert. The Count decided to spend the night in the room, but ended up leaving shortly after midnight, confused by the noises in the room… and the bed that had been overturned with both men in it. The next morning, the soldier had a new room.

Calmet also wanted to define what sort of creature goblins were. One story from Johannes Trithemius (d. 1516) showed what happened when a goblin was unappreciated. Hecdekin (spirit in a cap) lived in Hildesheim, Saxony, where he worked in the Bishop’s kitchen. After another servant offended him, Hecdekin complained to the head cook who proceeded to ignore him. Hecdekin “thought it proper to do himself justice”: strangling the servant, tearing him into pieces, and boiling him. This got everyone’s attention, who drove Hecdekin away by exorcism.

Calmet stressed goblins’ helpfulness and lack of malevolence, which meant that they were not devils. They only became dangerous when angered, like Hecdekin. But neither were they angels, their “waggish tricks” lacking dignity. Goblins were somewhere in between.

Brand classified the goblins linguistically. They were the same as Brownies in Scotland, related to fairies, and “a Kind of Ghost”. Brand believed that ‘goblin’ came from ancient Greek, meaning ‘house spirit’, and that hobgoblins were a species known for hopping on one leg. The name ‘Brownies’ referred to their swarthy colour, which came from their hard labour. The origin of the belief itself, Brand suggested, was Persia or Arabia. However, since Samuel Johnson had noted that no one had spoken of Brownies “for many years”, Brand thought they were extinct.

Goblin beliefs were, indeed, changing. Calmet might have dismissed the existence of vampires, but he believed in goblins because of good eyewitness accounts. William Bourne in 1725—and Brand who agreed with him—would have seen this as Calmet’s popish credulity. Goblins only flourished “in the benighted Ages of Popery, when Hobgoblins and Sprights were in every City and Town and Village”. These were stories told around winter fires that added “to the natural Fearfulness of Men, and makes them many times imagine they see Things”. Goblin extinction, then, was a move from superstitious excess (as Bourne and Brand saw it) towards reason. The classification of goblins was a way of putting them in their place.

Some of these stories are easily explained: a prankster in Pliny’s house, a murder in Hildesheim, a literary trope about terrified soldiers. All the same, if you should ever receive unexpected help around the house, remember to say thank you. Just in case.

[1] Augustin Calmet, Dissertation upon the apparitions of angels, demons, and ghosts, London, 1759. (Original French, 1746.)

[2] John Brand republished and added a commentary to William Bourne’s 1725 work on popular antiquities: Observations on popular antiquities: including the whole of Mr Bourne’s Antiquitates Vulgares, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1777.

Lisa Smith (@historybeagle) is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and teaches on medicine, natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in October 2013.

March 30, 2015

The Secret History of Cheese

By Gastropod (Regular Contributor)

This is the story you’ll often hear about how humans discovered cheese: one hot day nine thousand years ago, a nomad was on his travels, and brought along some milk in an animal stomach—a sort of proto-thermos—to have something to drink at the end of the day. But when he arrived, he discovered that the rennet in the stomach lining had curdled the milk, creating the first cheese. But there’s a major problem with that story, as University of Vermont cheese scientist and historian Paul Kindstedt told Gastropod: the nomads living in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East in 7000 B.C. would have been lactose-intolerant. A nomad on the road wouldn’t have wanted to drink milk; it would have left him in severe gastro-intestinal distress.

Kindstedt, author of the book Cheese and Culture, explained that about a thousand years before traces of cheese-making show up in the archaeological record, humans began growing crops. Those early fields of wheat and other grains attracted local wild sheep and goats, which provide milk for their young. Human babies are also perfectly adapted for milk. Early humans quickly made the connection and began dairying—but for the first thousand years, toddlers and babies were the only ones consuming the milk. Human adults were uniformly lactose-intolerant, says Kindstedt. What’s more, he told us that “we know from some exciting archaeo-genetic and genomic modeling that the capacity to tolerate lactose into adulthood didn’t develop until about 5500 BC”—which is at least a thousand years after the development of cheese.

The real dawn of cheese came about 8,500 years ago, with two simultaneous developments in human history. First, by then, over-intensive agricultural practices had depleted the soil, leading to the first human-created environmental disaster. As a result, Neolithic humans began herding goats and sheep more intensely, as those animals could survive on marginal lands unfit for crops. And secondly, humans invented pottery: the original practical milk-collection containers.

In the warm environment of the Fertile Crescent region, Kinstedt explained, any milk not used immediately and instead left to stand in those newly invented containers “would have very quickly, in a matter of hours, coagulated [due to the heat and the natural lactic acid bacteria in the milk]. And at some point, probably some adventurous adult tried some of the solid material and found that they could tolerate it a lot more of it than they could milk.” That’s because about 80 percent of the lactose drains off with the whey, leaving a digestible and, likely, rather delicious fresh cheese.

In the warm environment of the Fertile Crescent region, Kinstedt explained, any milk not used immediately and instead left to stand in those newly invented containers “would have very quickly, in a matter of hours, coagulated [due to the heat and the natural lactic acid bacteria in the milk]. And at some point, probably some adventurous adult tried some of the solid material and found that they could tolerate it a lot more of it than they could milk.” That’s because about 80 percent of the lactose drains off with the whey, leaving a digestible and, likely, rather delicious fresh cheese.

Cheese Changed the Course of Western Civilization

With the discovery of cheese, suddenly those early humans could add dairy to their diets. Cheese made an entirely new source of nutrients and calories available for adults, and, as a result, dairying took off in a major way. What this meant, says Kindstedt, is that “children and newborns would be exposed to milk frequently, which ultimately through random mutations selected for children who could tolerate lactose later into adulthood.”

In a very short time, at least in terms of human evolution—perhaps only a few thousand years—that mutation spread throughout the population of the Fertile Crescent. As those herders migrated to Europe and beyond, they carried this genetic mutation with them. According to Kindstedt, “It’s an absolutely stunning example of a genetic selection occurring in an unbelievably short period of time in human development. It’s really a wonder of the world, and it changed Western civilization forever.”

Tasting the First Cheeses Today

In lieu of an actual time machine, Gastropod has another trick for listeners who want to know what cheese tasted like 9,000 years ago: head to the local grocery store and pick up some ricotta or goat’s milk chevre. These cheeses are coagulated using heat and acid, rather than rennet, in much the same way as the very first cheeses. Based on the archaeological evidence of Neolithic pottery containers found in the Fertile Crescent, those early cheeses would have been made from goat’s or sheep’s milk, meaning that they likely would have been somewhat funkier than cow’s milk ricotta, and perhaps of a looser, wetter consistency, more like cottage cheese.

“It would have had a tart, clean flavor,” says Kindstedt, “and it would have been even softer than the cheese you buy at the cheese shop. It would have been a tart, clean, acidic, very moist cheese.”

So, the next time you’re eating a ricotta lasagne or cheesecake, just think: you’re tasting something very similar to the cheese that gave ancient humans a dietary edge, nearly 9,000 years ago.

Camembert Used to be Green

Penicillium camemberti growing in a petri dish in Ben Wolfe’s lab. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Those early cheese-making peoples spread to Europe, but it wasn’t until the Middle Ages that the wild diversity of cheeses we see today started to emerge. In the episode, we trace the emergence of Swiss cheese and French bloomy rind cheeses, like Brie. But here’s a curious fact that didn’t make it into the show: when Gastropod visited Tufts microbiologist Benjamin Wolfe in his cheese lab, he showed us a petri dish in which he was culturing the microbe used to make Camembert, Penicillium camemberti. And it was a gorgeous blue-green color.

Wolfe explained that according to Camembert: A National Myth, a history of the iconic French cheese written by Pierre Boisard, the original Camembert cheeses in Normandy would have been that same color, their rinds entirely colonized by Wolfe’s “green, minty, crazy” microbe. Indeed, in nineteenth-century newspapers, letters, and advertisements, Camembert cheeses are routinely described as green, green-blue, or greenish-grey. The pure white Camembert we know and love today did not become the norm until the 1920s and 30s. What happened, according to Wolfe, is that if you grow the wild microbe “in a very lush environment, like cheese is, it eventually starts to mutate. And along the way, these white mutants that look like the thing we think of as Camembert popped up.”

In his book, Boisard attributes the rapid rise of the white mutant to human selection, arguing that Louis Pasteur’s discoveries in germ theory at the start of the twentieth-century led to a prejudice against the original “moldy”-looking green Camembert rinds, and a preference for the more hygienic-seeming pure white ones. Camembert’s green origins have since been almost entirely forgotten, even by the most traditional cheese-makers.

Listen to this week’s episode of Gastropod for much more on the secret history and science of cheese, including how early cheese bureaucracy led to the development of writing, what studying microbes in cheese rinds can tell us about microbial ecology in our guts, and why in the world American cheese is dyed orange. (Hint: the color was originally seen as a sign of high quality.) Plus, Gastropod will help you put together the world’s most interesting cheese plate to wow guests at your next dinner party. Listen here for more!

March 26, 2015

Lenin’s Lamps

Arkady Shaikhet’s “Lenin’s Lamp” (1925)

By Eric Laursen (Regular Contributor)

In Arkady Shaikhet’s photograph “Lenin’s Lamp” (1925) two peasants examine a light bulb hanging from a cord that appears to be strung through the portrait of Mikhail Frunze, Bolshevik and son of a peasant. Electricity seems to be directed from Frunze’s mind and into the hands of the unenlightened peasant, whose traditional haircut and clothing contrast sharply with Frunze’s and point to the intended modernizing influence of the electrification campaign. In the early Soviet period, showing the light-bulb–nicknamed “Lenin’s lamp”–to the peasants became a demonstration of technology that Lenin claimed would “show the population, especially the peasants, that we have [. . .] broad plans which aren’t taken from fantasies, but supported by technology grounded in science.” The image showed up on posters, lacquered boxes, and even in a children’s cartoon. The light-bulb may seem a strange choice of evidence to prove that communism is not “fantasy,” but as seen in Shaikhet’s often-reproduced photograph, the light-bulb is endowed in Soviet propaganda with the significance of a religious artifact that merely needs to be touched or seen in order to work wonders. The peasant is presented in Bolshevik propaganda about electrification as a scapegoat for everything regressive in post-revolutionary Russia; Lenin writes: “[Electrification] will enable us to fully and decisively defeat that backwardness, that fragmentation, disintegration, the darkness of the countryside, that is to this point the main cause of all stagnation, all backwardness, all oppression.” Lenin presents electricity as a high-tech adhesive that could mend the “fragmentation, disintegration” of the countryside and meld the dark fragments into one cohesive brightly-lit whole, lighting up the darkness both literal and figurative. The primitive, flickering light of the peasant home and work-place would be replaced by Lenin’s lamps: “Cheap light energy from mighty regional electrical stations spreads around the whole country, goes right up to village huts with their wood-splinter torches and other home-grown means of illumination, overthrowing the coarse backwardness of village life.”

[image error]

“Electrification and Counterrevolution” (1921)

Repeatedly, Bolshevik propaganda argued that electricity would defeat capitalism, religion, hierarchy and exploitation. In the 1923 poster “Electrification and Counter-revolution” an enormous hand holds up one of Lenin’s lamps, and a group of stereotypical counterrevolutionaries representing the evils of the class system try to extinguish its light. To the left of the light bulb a fat capitalist crouches on his hands and knees so that a White general and an Orthodox priest can climb up on his back with a fire hose; to the right a fashionable gentleman fetches a bucket of water; and in the center a foreign diplomat attempts to blow out the light bulb with a small bellows. The tiny figures each wear identifying markers of the exploiting class—clerical garb, gold epaullettes, a top hat, a gentleman’s straw boater, and a monocle. They also wear technological ignorance and backwardness on their well-tailored sleeves. Under the electric light of the proletariat they become comic buffoons, motivated by fear and greed and fighting the progress of technology with the ineffectual weapons of a more primitive age. Embodied in the electrification campaign is the promise that with technological superiority comes moral purity. The proletarian hand, like the right hand of God, gives humanity the light of truth, guiding followers to the bright future and illuminating the technologically ignorant exploiters of humankind, so that they can be seen as cartoon figures, easily defeated by the mighty–electrified–Soviet hand.

[image error]

Cover of “We Build” (1929)

As we can see in the cover of the November 7, 1929 issue of We Build, a Soviet journal dedicated to construction photography, after his death in 1924, Lenin’s image became inextricably linked to the lamps that carried his name and that fought the darkness of ignorance. Here Lenin’s head is enclosed in an enormous light bulb, a fusion of human and technology that gives new meaning to the term “Lenin’s lamp.“ Below the disembodied Lenin’s lamp, we see one of the massive hydroelectric dams envisioned by the electrification campaign and the constructions enabled by their power. A power tower is pictured in the upper right-hand corner. Moving diagonally down the page and separating the picture of the construction site from the picture of the electric tower is a series of letters forming steps that spell out: “XII October is a New Step toward Socialism,” in large font in Russian and in smaller letters in German and English–to show the triumph of Soviet construction over the leading industrialized countries of the world. In this tribute to the twelfth anniversary of the October revolution and the first five-year plan, Lenin’s head becomes a source of light for everything contained in the picture; and, by implication, in the journal issue that follows. The power goes both ways. The lines connecting the base of the light-bulb to the tops of cranes and the roofs of factories also charge up the light-bulb and by implication the memory of Lenin, who “lived, lives, and will live” in memorials like this one that help the Soviet people move up the stairway to socialism. According to the circular logic displayed in the image, each year after the revolution takes another “step toward socialism” through the human energy that accomplishes monumental construction feats, and it also produces energy for revolutionary enlightenment that will push the Soviet people up one more step. The cult of Lenin and technology that is powered by the head in the light bulb is an energy loop of propaganda and construction, each of which feeds energy to the other.

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in February 2013.

March 24, 2015

Late Admission: California High Court Corrects 125-Year-Old Wrong

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

On March 16, 2015, a lawyer won admission to the California State Bar, as thousands of attorneys do every year. In this case, however, the newly admitted lawyer had petitioned for entry 125 years earlier and died in 1926.

Hong Yen Chang

Justice moved slowly for Hong Yen Chang, a naturalized U.S. citizen of Chinese origin, but it did eventually move. This month the Supreme Court of California gave Chang the license to practice law that state and federal legislation denied him during the nineteenth century.

Chang first arrived in the U.S. in 1872, at the age of 13, as part of a Chinese cultural and educational mission. He studied at Andover, Yale, and Columbia Law School before overcoming multiple obstacles to gain entry to the New York State Bar in 1888. What hindered his admission was the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred Chinese immigrants from receiving U.S. citizenship, a requirement of bar membership. Only after the New York Assembly specially exempted him from the Act and permitted his naturalization would the state bar accept him.

Chang’s real problems began two years later, when he decided to move his law practice to California to assist the large number of Chinese immigrants there. When he applied to join the California Bar and presented his New York credentials, he was turned away. In 1890 the Supreme Court of California issued a notorious ruling that found Chang’s New York naturalization invalid and declared him ineligible for bar membership on account of his race.

Chang never did practice law in California, although he went on to pursue an illustrious career in diplomacy and banking before he died at age 67 in Berkeley.

In unanimously overturning its 125-year-old decision, the California Supreme Court observed that “it is past time to acknowledge that the discriminatory exclusion of Chang from the State Bar of California was a grievous wrong.” Chang’s belated admission was made possible by a petition that students in the Asian Pacific American Law Students Association at the University of California-Davis had filed with the state court.

Further reading:

Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. Viking, 2003.

Farkas, Lani Ah Tye. Bury My Bones in America: The Saga of a Chinese Family in California, 1852-1996. Carl Mautz Publications, 1998.

Princess Sophia the Suffragette

By Anita Anand (Guest Contributor)

I am often asked how I found Sophia but honestly, she found me. I was on maternity leave in 2010 when one morning, a local magazine landed on my mat. As I turned the pages I became transfixed by a single image – a brown-skinned woman dressed as an Edwardian lady, selling copies of a militant suffragette newspaper. She looked Indian.

I am a political journalist of Indian origin, so naturally found myself drawn. I tugged on a thread and an avalanche of a story fell. Princess Sophia Duleep Singh would take me on one of the greatest journalistic adventures of my life.

I am a political journalist of Indian origin, so naturally found myself drawn. I tugged on a thread and an avalanche of a story fell. Princess Sophia Duleep Singh would take me on one of the greatest journalistic adventures of my life.

Princess Sophia Jindan Alexandrovna Duleep Singh was a dispossessed Princess of one of the greatest and most defiant empires of the Indian subcontinent. Her grandfather was a one eyed warrior King who united northern India and terrified the British.

After his death in 1843, Sophia’s father, Maharajah Duleep Singh took the throne aged just 5. Sensing the chance for a land grab, the British befriended the boy and then betrayed him. Duleep was exiled, and ended up in Britain, where he enjoyed great favour from Queen Victoria. She adored him and gladly became Sophia’s godmother when she was born in 1876.

The relationship turned toxic however, when the Maharajah tried and failed to take back his Kingdom. His obsession caused him to discard Sophia and her mother. Queen Victoria appointed guardians who cared for the little girl, left crippled by the insecurity of her abandonment. Together, they and the Queen rebuilt her. Sophia was given a home at Hampton Court Palace, and filled newspapers with her trend setting fashion sense. She became quite the girl about town.

From Girl About Town to Suffragette

A prohibited trip to Punjab at the turn of the century, however, changed everything. She came to understand just how much had been taken from her family and from India. With a burning sense of injustice, Sophia sailed back to Britain and found an outlet for her rage.

Sophia became an ardent and committed member of Emmeline Pankhurst’s army. She drove carts of Suffragette newspapers through London, embarrassing former friends at Buckingham palace. She fought with police, battling in the midst of violent riots, even throwing herself at the Prime Ministers car. She refused to pay her taxes, daring the authorities to arrest her, longing to go on hunger strike like her sister suffragettes.

The one-time darling of the establishment was now denounced from the highest orders. This is the story of her life and transformation.

Anita Anand has been a radio and television journalist for almost twenty years. She is the presenter of Any Answers on BBC Radio 4. During her career, she has also presented Drive, Doubletake and the Anita Anand Show on Radio 5 Live, and Saturday Live, The Westminster Hour, Beyond Westminster, Midweek and Woman’s Hour on Radio 4. On BBC television she has presented The Daily Politics, The Sunday Politics and Newsnight. She lives in west London. This is her first book.

Anita Anand has been a radio and television journalist for almost twenty years. She is the presenter of Any Answers on BBC Radio 4. During her career, she has also presented Drive, Doubletake and the Anita Anand Show on Radio 5 Live, and Saturday Live, The Westminster Hour, Beyond Westminster, Midweek and Woman’s Hour on Radio 4. On BBC television she has presented The Daily Politics, The Sunday Politics and Newsnight. She lives in west London. This is her first book.

March 23, 2015

Sita Sings The Blues

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

The Ramayana is one of the classic Indian epics. Ascribed to the great Sanskrit poet-sage, Valmiki, it’s a love story, a moral lesson, and/or a foundation myth, depending on what kind of reader you are. Boy gets girl. Boy loses girl to demon king. Boy rescues girl with the help of monkey-god. Boy worries that girl’s virtue has been smirched and puts her to ordeal by fire. Girl comes through ordeal triumphantly. Boy bows to public pressure and banishes girl to the forest, where she gives birth to twin sons. Boy finds girl again and they live happily ever after.

The story has had an enormous impact on art and culture in India. It has inspired poets in almost every Indic language, most notably the version by 16th century poet Tulsidas. The folk play Ramlilla is performed all over India and the Hindu diaspora as part of the Dusshera festival. Rama and Sita are the romantic leads in countless Hindi movies. And in almost every case, the story focuses on Prince Rama–it is after all the Rama-yana.

In Sita Sings the Blues, American cartoonist and animator Nina Paley turns the spotlight on Sita. Her animated version of the story is colorful, complex and edgy. Using multiple animation styles, Paley interweaves a straightforward, if Sita-centric, version of the Ramayana with commentary on the story by a trio of modern Indians (represented by Indonesian shadow puppets), a modern-day story of a relationship gone wrong, and musical numbers that are part Bollywood and part 1920s jazz singer. The result is an engaging, often hysterical, feast for eyes, ears, and mind.

(A word of warning: My Own True Love was not familiar with the story of the Ramayana and found the action a little hard to follow. If you’re in his shoes, you might want to read this quick plot summary before you view.)

For those of you who subscribe by e-mail, click through to the blog home page if you want to see the trailer for the film, posted at the top of the page.

March 20, 2015

Of Cows and Men

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

“The deviation of Man from the state in which he was originally placed by Nature seems to have proved to him a prolific source of Diseases. From the love of splendour, from the indulgences of luxury, and from his fondness for amusement, he has familiarised himself with a great number of animals, which may not originally have been his associates.

The Wolf, disarmed of his ferocity, is now pillowed in the lady’s lap. The Cat, the little Tyger of our island, whose natural home is the forest, is equally domesticated and caressed. The Cow, the Hog, the Sheep and the Horse, are all, for a variety of purposes, brought under his care and dominion.”

Edward Jenner, “A Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae” (1798)

This might appear an unusual introduction to a scientific paper, but Edward Jenner’s lyrical description of Man’s domestication of animals was written in anticipation of the horror he knew his innovation would evoke. His “vaccine” against smallpox, proposed in 1798, was so-called because it involved infecting humans with cowpox in order to protect them against the much more dangerous human disease: vacca is the latin word for cow.

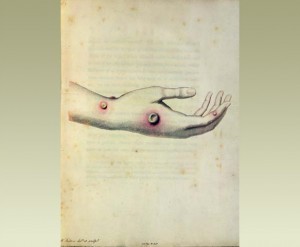

Jenner’s vaccine proved highly effective, and is considered to have saved countless lives in the course of the nineteenth century, when its introduction consistently reduced the smallpox mortality rate by 90% (the introduction of compulsory vaccination cut smallpox deaths by another third, on average). Yet Jenner was sufficiently anxious about the reception of his technique that he chose to publish his results himself, rather than submit them to the Royal Academy of Science. He knew that infecting humans with an animal disease would prove especially controversial. In fact, rather than directly infect a human for his experiments, he used the pus from the sore a milkmaid who had already contracted cowpox naturally, Sarah Nelmes. The boy he vaccinated with this matter later had almost no reaction to inoculation with smallpox, indicating that the cowpox vaccine had indeed conferred immunity. Inoculation (deliberately giving a healthy individual a mild case of smallpox to generate immunity) was already widespread by the late 18th century, but it carried the risk of potentially spreading smallpox, which is why Jenner’s cowpox method was so lauded.

Resistance

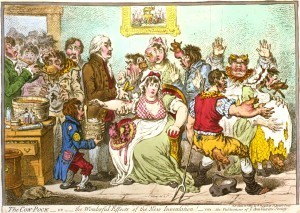

The vaccine did not meet with universal acclaim, however, and as Jenner anticipated, the association with animals was the cause of particular disdain and disapproval. James Gilray’s caricature “The Cow Pock, or the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation!” (1802) mocks this reaction, showing recipients of the vaccine developing bovine features and sprouting miniature cow heads.

The “unnatural” mingling of human and beast continued to distress anti-vaccinators a century later:

The “unnatural” mingling of human and beast continued to distress anti-vaccinators a century later:

“Vaccination is a loathsome disease of uncertain origin, artificially transmitted, through various beasts and capable of setting up a variety of repulsive, dangerous, and even fatal affections.” (The Vaccination Enquirer, 1914)

While Charles Dickens was a prominent advocate of compulsory vaccination, George Bernard Shaw described it as “a particularly filthy piece of witchcraft.”

State of Nature

Jenner’s opening passage is intriguing, because it alludes to both the hypothetical “state of nature” of natural rights theory and to the Fall of Man in Genesis. Through his dominion over animals, Jenner explains, Man is responsible for their “degeneration” and for diseases that result from domestication. Female sensuality and concupiscence is especially to blame: it is in the “lady’s lap” where the wolf has been “disarmed,” as Eve’s congress with the serpent led to the expulsion of Man from Eden.

Writing for a largely Christian audience whose hesitation towards vaccination was motivated by faith too, Jenner cleverly employed these biblical allusions in order to place the use of cowpox to treat humans within the norms of the modern –albeit fallen – world.

For Jenner’s full text, see Edward Jenner, “A Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae” (1798)

On the history of smallpox, see Ian and Jennifer Glynn, The Life and Death of Smallpox (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004)