Holly Tucker's Blog, page 31

June 1, 2015

Roman Fascination with Amazons

by Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

When a Roman senator questioned Julius Caesar’s manhood, his unexpected retort was to compare himself to powerful Amazon warrior-queens. A few years earlier, in 61 BC, during his Triumph after the Mithradatic Wars, Pompey had displayed a troop of living Amazons, warrior women he captured in 65 BC in eastern Georgia. Romans were already very familiar with Amazons in ancient Greek literature and art. In Rome one could admire copies of classical Amazon statues from the great temple at Ephesus. Wearing short tunics with one breast undraped, they carry quivers, bows, spears, and crescent shields, and some are wounded. The women’s expressions are austere, beautiful, heroic, vulnerable, androgynous.

Many small copies survive of a magnificent Amazon astride a rearing horse by the Greek sculptor Strongylion, plundered from Ephesus by a Roman connoisseur. Her sensuous limbs inspired her nickname in Rome: “Lovely Legs” (from Euknemon, Greek for “beautiful knees”). The emperor Nero developed a crush on this bronze statue and confiscated it from the owner. From then on, Nero insisted that “Lovely Legs” was always carried by porters in his retinue. Nero also surrounded himself with an entourage of “Amazon” concubines with boyish haircuts in Amazon garb and brandishing battle-axes and light shields.

The emperor Commodus was another Amazon fetishist. He renamed the month of December “Amazonius” and sealed his letters with a signet ring depicting an Amazon. His marble portrait bust depicts Commodus dressed up like Hercules with two kneeling Amazons at the base. He called his girlfriend Marcia (“Warlike,” after the Roman war god Mars) and outfitted her like an Amazon to fight as a gladiator in the arena. Latin texts describe female gladiators playing the roles of Amazons in re-creations of the mythic duels between Greeks and Amazons in the Trojan War.

An amazing sculpted relief in the British Museum, found in Halicarnassus (Turkey) in 1846, shows a pair of bare-breasted female gladiators with greaves and shields fighting with short swords. The inscription gives their noms de guerre, “Amazon” and “Achillia.” We can imagine that these fighters were famous for impersonating Achilles and the Amazon queen Penthesilea. Some suggest that a bronze statuette of a topless female athlete with a bandaged knee depicts a gladiatrix in a victory pose (first century AD). A much older small bronze of two women in close combat (British Museum) from Erythrae (Turkey) is dated to the 6th century BC. In 2010, archaeologists excavating a Roman town in Herefordshire announced the discovery of what appear to be the remains of a female gladiator in an expensive coffin (2nd century AD).

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014).

May 30, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: History Goes Underground

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

When you think of underground history, you may imagine slaves escaping on the Underground Railroad, or other types of subterfuge and secrecy throughout history. For once, this week we are not speaking figuratively: we are literally uncovering stories about history underground.

Most people are familiar with London’s Underground transportation system, more commonly called the tube. Fewer people know about London’s other underground: the pneumatic railway. During the Victorian Age this air-propelled form of transport was vying with steam engines and cable systems to rule the transportation sector. Learn all about the lost pneumatic railway on London Reconnections.

Long before the Tube or the pneumatic railway, inhabitants of the British Isles were going underground. While performing road work, construction workers uncovered a 1,000 year old passageway in Caha Mountains of Ireland. This passage, called a “souterrain”, could have been used for storage, or refuge in times of strife.

Beneath the Gunfire

The image of the Great War fought from the trenches is one that lives on in photographs and on movie screens. In actuality, most of these trenches have long been covered with farms and hedgerows, as they were before World War I. Yet, there is one such trench that is perfectly preserved in the Belgium country overlooking Ypres. Now called Sanctuary Wood, this site privately owned by the Schier family gives visitors a feel about what it really meant to fight from the trenches.

The image of the Great War fought from the trenches is one that lives on in photographs and on movie screens. In actuality, most of these trenches have long been covered with farms and hedgerows, as they were before World War I. Yet, there is one such trench that is perfectly preserved in the Belgium country overlooking Ypres. Now called Sanctuary Wood, this site privately owned by the Schier family gives visitors a feel about what it really meant to fight from the trenches.

World War II was also fought from the trenches, but the Japanese planned to go even further underground if necessary. When the end of the war was nigh, a secret plan to relocate the capital and save the emperor was put in place. The scheme was to dig tunnels under Mt. Zozan in Nagano creating the Matsushiro Underground Imperial Headquarters. The nearly 5,900 meter long tunnel was meant to host government agencies and included a palace for the Emperor and his family.

Below Sea Level

You may enjoy visiting caves or catacombs turned museums, but how would you feel about exploring a museum underwater? Far from an aquarium or diving expedition, an archaeologist in Egypt is envisioning an underwater museum in Alexandria. After a powerful earthquake, the ancient city of Alexandria was submerged under the Mediterranean Sea and though archaeologists have recovered many antiquities and brought them to dry land, many priceless treasures remain at the bottom of the sea, quite literally. Would you brave the waters to get a glimpse of ancient Alexandria?

You may enjoy visiting caves or catacombs turned museums, but how would you feel about exploring a museum underwater? Far from an aquarium or diving expedition, an archaeologist in Egypt is envisioning an underwater museum in Alexandria. After a powerful earthquake, the ancient city of Alexandria was submerged under the Mediterranean Sea and though archaeologists have recovered many antiquities and brought them to dry land, many priceless treasures remain at the bottom of the sea, quite literally. Would you brave the waters to get a glimpse of ancient Alexandria?

If you enjoyed these new discoveries, take a look at some of our recent stories on Wonders & Marvels:

Female Samurai: Warriors and Otherwise

Want more to read? Don’t forget to register for our Monthly Book Giveaways!

May 28, 2015

The Cloister and Accounts Payable

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (Former Regular Contributor)

When I began doing research on early modern convents, one of my favorite finds in the archives was their account books. At first glance they were impenetrable. Only by spending hours paging through through them carefully did their internal logic reveal itself. There is no double-entry bookkeeping, for example. Expenditures are grouped together and then all sources of income are listed collectively. Once I got acclimated to their format, I realized that they were a treasure trove of information about convent life. Take, for example, the books from the convents of Santa Isabel and Santa María de las Huelgas, both located in the city of Valladolid.

Page from the archives of Santa Isabel de Valladolid

At the turn of the seventeenth century, the pages of these account books reveal that the nuns consumed meat, fish, wine, oil, and eggs with some regularity. “As was customary” the nuns of Santa Isabel were allowed to enjoy pastries at Sunday dinner. The nuns employed a variety of personnel to help them manage their properties and estates. Since normally women were prohibited from performing the sacraments they also had to hire and pay priests to perform these tasks [see my last post for interesting cases of when women could perform sacraments].

The nuns also had to maintain the liturgical life of the community. They purchased items like wax and missals. Music was central to their devotional life; the accounts record expenditures for bellows for an organ and strings for a harp.

Just like their secular counterparts, the nuns were constantly having to do maintenance on their physical plant: repairing a sewer; paying someone to pave a walkway, rebuilding chimneys, walls, and doors. They might also pay large sums of money to local artisans for more elaborate projects like repairs to an upper cloister or the commissioning of an altarpiece.

Yet perhaps the most intriguing insight that comes from the pages of these books is that convent officers were responsible for all of this activity and the bookkeeping and responsibilities that it generated. The books include the signatures of nuns who handled money and acted as stewards and accountants. Twice yearly, the abbess added her signature to the records. Despite the fact that their male contemporaries did not think them capable of rational administration, the evidence yielded by these weathered books makes clear that these women managed their resources efficiently and carefully.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She is currently at work on a project exploring the material culture of convents in early modern Europe.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in December 2011.

May 26, 2015

Seeing the World from Home in the 19th Century

By Amy G. Richter (Guest Contributor)

One of the great ironies of American Victorianism was the way in which nineteenth-century Americans asserted the separation of public and private only to mingle the two spheres again and again. More than mere hypocrisy, this tendency to divide and recombine private and public reflected a faith in the power and meaning of home. The permeability of domestic spaces and the malleability the home ideal only increased home’s cultural significance.

Figure 1

For example, in 1816, Charles Lloyd’s Travels at Home and Voyages by the Fire-side for the Instruction of Young Persons invited families and friends to gather in their parlors and imagine themselves part of a traveling party. Despite the intended domestic setting for his work’s enjoyment, Lloyd carefully recreated the breathlessness of the tourist’s race to see as many sights as possible. He explained, “As we have but little time to stay in America, we cannot describe its numerous towns minutely…. We must set out and proceed hastily toward Quebec, which is yet at great distance.”

Why the hurry? The imagined inconveniences of travel no doubt enhanced the pleasure of an evening by the hearth. Lloyd’s readers viewed awe-inspiring natural wonders free of risk; wandered the streets of strange cities in safety; visited distant attractions amid perfect comfort. The juxtaposition of private space and public imaginings heightened the pleasures of vicarious travel. Indeed throughout the nineteenth century, domesticated travelers read guidebooks, played board games, and viewed stereographs, all the while touring the world from the privacy and contentment of home (Figure 1).

Figure 2: Bedroom of Marie Antoinette

Inverting this formula, the 1893 Columbian Exposition rendered touring the world as easy and accessible as a series of house visits. Planned in honor of the four hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing in America, the Exposition included forty-six countries and over two hundred buildings. In the context of the fair’s self-conscious cosmopolitanism, visitors who strolled through the neoclassical White City and the ethnological exhibits of the Midway Plaisance also took in displays of domestic spaces – a primitive cliff dwelling, the bedroom of Marie Antoinette (Figure 2), a Ceylon tearoom, a hunter’s cabin built by Theodore Roosevelt (Figure 3). Each “home” permitted Americans to imagine their place in the world, as domestic practices and spaces provided a recognizable vocabulary for comparing nations and peoples. (Who would live in a cliff? What was it like to live in such luxury? How unusual!)

Figure 3: Hunter’s Cabin

At home and in public, domesticity provided nineteenth-century Americans with the tools and vocabulary to make sense of the world. Exposition exhibits reminded fairgoers of the double meaning of “domestic,” denoting both home and nation. Photographs of domestic displays, preserved in souvenir albums for future armchair travelers, helped viewers rank nations and peoples; an appreciation for the private and comfortable American home provided all the necessary expertise. In the words of one tourist brochure: “Between the Hunter’s Cabin and Marie Antoinette’s bed-chamber in the French section there was a wide divergence.” What more need be said?

Amy G. Richter is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Higgins School of Humanities at Clark University. Her recent book At Home in Nineteenth-Century America: A Documentary History draws upon advice manuals, architectural designs, personal accounts, popular fiction, advertising images, and reform literature to offer a broad interpretation of home’s place in American culture, politics and daily life.

Amy G. Richter is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Higgins School of Humanities at Clark University. Her recent book At Home in Nineteenth-Century America: A Documentary History draws upon advice manuals, architectural designs, personal accounts, popular fiction, advertising images, and reform literature to offer a broad interpretation of home’s place in American culture, politics and daily life.

May 25, 2015

Female Samurai: Warriors and Otherwise

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

The powerful Tomoe Gozen. Shuntei Katsukawa. ca. 1804-1818

Female samurais are stock figures in modern anime, manga, western comic books, and fantasy novels: hard-fighting, often hard-drinking, badasses with swords and bows. The key word is fantasy.

In medieval Japan, samurai was a class distinction as well as a job description. Women who were born into the samurai class were samurais whether or not they were warriors. As members of the warrior class, they shared the martial code of loyalty and honor known as bushido. Many of them were trained to use the naginata–a deadly scythe-like weapon–and carried razor-sharp daggers on their belts. They shared the disgrace when their male relations failed on the battlefield, following them into exile and even death.

Only a few samurai women became samurai warriors, but their stories form a constant thread through Japanese history. The most famous was the twelfth century warrior Tomoe Gozen, who fought alongside Minamoto Kiso Yoshinaka in the Gempei War* and collected enemy heads as battle trophies just like one of the guys. Her story became the subject of songs and a popular Noh play. But Tomoe was not the only female samurai to fight in Japan’s seemingly interminable internal wars. Tsuruhime, known as the sea princess of Omishimia, defended that island against expansionist threats from the Japanese mainland in 1541. Thirty-six years later, Ueno Tsuruhime led thirty-three other women in a suicidal charge against the army of a rival warlord–preferring to die in battle than commit the ritual suicide prescribed by her husband. (The tactic failed. The besieging samurai proved reluctant to kill women who fought back.) Near the end of the Amakusa rebellion in 1589-90, the wife of the castle commander of the largely Christian stronghold at Hondo and several hundred other women cut off their long hair, tied up the hems of their kimonos, armed themselves with weapons and rosaries, and sortied from the broken castle gate in a final desperate attack.

Even in nineteenth century, when the world of the samurai was coming to an end, some women from samurai families joined their fathers, husbands, and brothers on the battlefield against the forces of the Meiji emperor. In Daughters of the Samurai, Janice Nimura tells the story of one young woman who tried to take a more active role in the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877. With her family stronghold under siege, “the teenager scavenged pieces of discarded armor, chopped off her hair, pulled down the corners of her mouth in a classic samurai grimace, and announced that she was off to join the fighting.” In this case, the samurai value of obedience won out over the samurai value of courage–when her mother forbade her to leave the castle she stayed put. But other women, old enough or stubborn enough not to be controlled by parental commands, chose to fight rather than fulfill more traditional roles related to the defense of a stronghold or commit ritual suicide. In one extraordinary case, Kawahara Asako decapitated her mother-in-law and daughter to save them from dishonor at the hands of the enemy before she took up her naginata and joined the fight against the imperial army.

With the exception of Tomoe Gozen, who appears to have fought because she was good at it, these stories share common themes of defense and desperation. A far cry from their modern pop culture descendants.

*In which two samurai clans–the Taira and the Minamoto–duked it out for control of Japan. The Gempei War ended with the Minamoto’s victorious establishment of the first shogunate–a form of government by military dictatorship in the name of a puppet emperor that would last in various forms from 1192 to 1867. In case you were curious.

May 21, 2015

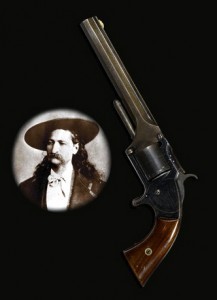

It Didn’t Save Wild Bill

By Caroline Lawrence (Guest Contributor)

While researching my second Western Mystery for kids, P.K. Pinkerton and the Petrified Man (AKA The Case of the Good-looking Corpse), I discovered a fascinating fact: very few gunfights played out like the iconic Western movie “showdown”. Two antagonists rarely faced each other like self-moderating duelists on Main Street, one honorably waiting for the other to “draw”. More often one man would “throw down” on another without warning, sometimes even shooting from behind through a window or door.

While researching my second Western Mystery for kids, P.K. Pinkerton and the Petrified Man (AKA The Case of the Good-looking Corpse), I discovered a fascinating fact: very few gunfights played out like the iconic Western movie “showdown”. Two antagonists rarely faced each other like self-moderating duelists on Main Street, one honorably waiting for the other to “draw”. More often one man would “throw down” on another without warning, sometimes even shooting from behind through a window or door.

One night in 1876 in a Deadwood saloon, a famous gunfighter with silky golden locks was shot in the back of the head while playing poker. The shooter, a certain Jack McCall, fled. Hurdy girls screamed and other gamblers recoiled in horror. Wild Bill Hickok, already a legend in his own time, was dead. The reputed inventor of the “fast draw”, Hickok usually took a seat in a corner of a saloon or against wall, so nobody could sneak up on him. But on that fatal night he sat with his back exposed. Perhaps he was feeling tired of life. He was an alcoholic who rubbed mercury on his skin to alleviate the symptoms of venereal disease. This poisonous treatment made him drool and start to lose his sight. According to Deadwood author Pete Dexter, it often took him twenty minutes to empty his bladder.

As Hickok slumped onto the table, the five cards in his hand fell on the floor, spattered with drops of blood. Legend has it that he held two pair – black aces and a pair of black eights – that would later come to be know as the ‘Dead Man’s Hand’. He did not even have time to reach for his own weapon.

That weapon was an old-fashioned revolver – a Smith & Wesson number two six-shooter – which had first gone into production more than fifteen years before. Unlike fiddly cap and ball revolvers, which required the user to combine the ingredients for a bullet in each chamber of the cylinder, the Smith & Wesson had powder, ball and charge encased in a single cartridge. Protected by this rimfire “bullet”, the powder would never grow damp, the ball would never fall out and the charge would never misfire. You could just put a new cartridge into the cylinder. You could even pop out an entire used cylinder and put in a new one with six cartridges pre-loaded in.

In Roughing It, Mark Twain’s account of his days in the Wild West, he describes his own pistol. “I was armed to the teeth with a pitiful little Smith & Wesson’s seven-shooter,” he writes, “which carried a ball like a homoeopathic pill, and it took the whole seven to make a dose for an adult.” The Smith & Wesson Number 1 took seven .22 caliber cartridges. The new improved Number 2 took six cartridges rather than seven, and they each held a bigger .32 caliber ball, (i.e. the diameter of the ball was about a third of an inch.) Like the Number 1, the Number 2 had a spur trigger which only popped out when you cocked it. This new improved second-edition was so popular that Smith & Wesson had to stop taking orders at one point of production until they could catch up with demand.

Hickok’s Smith & Wesson Number 2 had a pretty rosewood grip and blued steel barrel. Sheriff Seth Bullock took it from Hickok’s cooling body and sold it to help pay off the gunfighter’s debts. It then passed from one generation to the next, one of the best documented firearms ever to go on sale.

Yes, on Monday 18 November 2013 this famous revolver will go up for auction in San Francisco, and is expected to fetch as much as half a million dollars… maybe more.

Until then it will be on show along with other early pistols and items of armour at Bonham’s auction house on 220 San Bruno Avenue in the Mission District. Viewing is free to the public and starts at high noon on Friday 15 November. If you are in San Francisco, come along and have a look at a famous piece of Western history. I might see you there!

[Update on Tues 19 November 2013: The famous revolver failed to meet the reserve price and bidding stalled at $220,000… so you might have another chance to see it.]

Caroline Lawrence is a children’s author who won the Classical Association Prize for her Roman Mysteries series. In 2011 Caroline launched a second historical detective series, the Western Mysteries, staring P.K. Pinkerton: a 12-year-old doubly orphaned detective.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in November 2013.

May 19, 2015

How Does Your Book Collection Compare with the Hoard of Bibliomaniac Richard Heber?

By Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

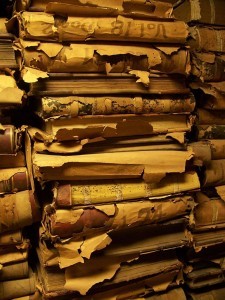

It’s safe to bet that if you’re a Wonders & Marvels visitor, you love reading and may have a sizeable book collection. But how does your fondness for books stack up against the obsessive hoarding of one of history’s most formidable bibliomaniacs, Richard Heber?

Heber, born in London in 1773 or 1774 into the family of a wealthy clergyman, was already a longtime habitué of bookshops and auctions by the time he enrolled at Brasenose College, Oxford. Despite his family’s efforts to curb his habit, Heber’s book purchases spiraled him into debt and filled his rooms with old and rare volumes. Unlike some sufferers of bibliomania, Heber actually did read some of the books he compulsively acquired, and he built a middling reputation as a scholar of English and classical literature.

After his father died and left Heber a fortune, all financial fetters were gone. “It seemed as if he wanted to own every book that ever was, and not just one copy of each,” John Michell wrote in Eccentric Lives and Peculiar Notions. “He used to say that every gentleman needed at least three copies of a book, one for his country house library, one for reading, and one to lend to friends.” His acquaintances characterized his hunger for books as insatiable and compared his lust for printed material to the yearnings of drunkards and opium addicts. In an era of difficult travel, Heber would journey hundreds of miles for a book he had targeted, and he sometimes bought books several thousand at a time. Only once did he contemplate marriage, and he and the woman he courted regarded the union primarily as a merger of book collections. In the end, Heber stayed single and their libraries remained separate.

In 1833, Heber died a recluse in the London house where he kept much of his gigantic collection hidden from the eyes of others. (One of his final acts had been to place an order with a bookseller.) When news spread of Heber’s death, a chronicler of bibliomania named Thomas Frognall Dibdin rushed to the house to view the legendary stash. “I had never seen rooms, cupboards, passages, and corridors, so choked, so suffocated, with books…. Up to the very ceiling the piles of volumes extended; while the floor was strewn with them,” Dibdin wrote. And Heber had jammed his seven other residences across Europe with uncountable additional books.

Years earlier, Heber’s book fixation had inspired the Scottish physician and poet John Ferriar to write and publish a long set of verses, titled The Bibliomania. It begins by questioning

What wild desires, what restless torments seize

The hapless man, who feels the book-disease,…

Heber undoubtedly had multiple copies of Ferriar’s book in his collection.

Further reading

Dibdin, Thomas Frognall. Bibliomania: or Book-Madness, a Bibliographical Romance. Henry G. Bohn, publisher, 1842.

Michell, John. Eccentric Lives and Peculiar Notions. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002.

Defiant Dressing: What Joan of Arc Wore

By Helen Castor (Guest Contributor)

Joan of Arc is an icon so familiar that her image is immediately recognizable: a short-haired girl in shining armor, brandishing a sword and a silken banner.

Joan of Arc is an icon so familiar that her image is immediately recognizable: a short-haired girl in shining armor, brandishing a sword and a silken banner.

It’s an image rooted in history as well as iconography. Sword, banner and armour can all be traced in the historical record; her sword was found, we’re told, in the church of Sainte-Catherine-de-Fierbois, and her banner and armour made specially for her before she was sent to fight at Orléans in 1429.

But what did Joan wear when she was not riding with her troops? And how did contemporaries react to what we would call her cross-dressing?

At first, Joan’s decision to wear male clothes seems to have been a practical one. She faced a 250-mile journey through enemy territory from her home in Lorraine to the Dauphin’s court at Chinon, with six men-at-arms for company. The people of the town where her journey began gave her a tunic, doublet, breeches and hose, all in black and grey, to replace her rough red dress – a disguise that offered advantages of speed, because she would be able to ride astride, and some measure of protection against sexual assault, in the form of the cords that tied hose and breeches to doublet.

By the time she reached Chinon, however, Joan’s distinctive appearance seems to have been absorbed into her sense of her mission. We don’t know for certain if she ever put on a dress at court before her victory at Orléans, but afterwards, when the duke of Orléans made her a gift of a fine outfit, it was male garments that the tailor was ordered to prepare – so our image of the historical Joan should include the Maid dressed in silks and satins like the debonair gentlemen of the royal household.

But the sight of a girl dressed as a boy was challenging as well as distinctive. After all, the Old Testament Book of Deuteronomy described a woman in men’s clothing as ‘an abomination unto the Lord’. For Joan’s supporters, this transgression could be excused because of her heaven-sent mission, but for her enemies it was proof that she communed not with God but the Devil. The prosecutors at her trial in 1431 saw her clothes as the visible manifestation of her heresy – and they were equally symbolic for Joan herself. Throughout her interrogation she refused to give up her male attire until at last, terrified by the imminent prospect of the flames, she capitulated and acknowledged her guilt. Three days later, unable to live with what she had done, she signaled her renewed defiance by dressing once again as a man.

Which leaves us with one last question about Joan’s clothes. Once she had agreed, as a repentant heretic, to put on a dress, who left her male outfit in her cell? If Joan was determined to die for her mission, it seems that some of her captors, at least, were happy to help her on her way.

Helen Castor is a historian of medieval England, and a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. Her first book, Blood and Roses, was long-listed for the Samuel Johnson Prize in 2005 and won the English Association’s Beatrice White Prize in 2006. Her last book, She-Wolves, was selected as one of the books of the year for 2010 in the Guardian, Times, Sunday Times, Independent, Financial Times and BBC History Magazine. She lives in London with her husband and son.

Helen Castor is a historian of medieval England, and a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. Her first book, Blood and Roses, was long-listed for the Samuel Johnson Prize in 2005 and won the English Association’s Beatrice White Prize in 2006. Her last book, She-Wolves, was selected as one of the books of the year for 2010 in the Guardian, Times, Sunday Times, Independent, Financial Times and BBC History Magazine. She lives in London with her husband and son.

W&M is excited to have two (2) copies of Joan of Arc: A History in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on May 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

May Book Giveaways

Jonathan Schneer, “Ministers at War: Churchill and His War Cabinet”

Henry Hemming, “The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy”

Helen Castor, “Joan of Arc: A History”

Diana Preston, “Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy”

May 18, 2015

Dying of Homesickness, from San Francisco to Versailles

by Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

The word ‘homesick’ entered the English language sometime in the eighteenth century. In French the phrase is ‘mal du pays,’ and before the nineteenth century, the phrase to indicate homesickness was ‘maladie du pays’, indicating something closer to physical sickness. In fact, until the twentieth century, homesickness was thought to be a potentially fatal ailment. The medical term for the disease was simply ‘nostalgia’.

The word ‘homesick’ entered the English language sometime in the eighteenth century. In French the phrase is ‘mal du pays,’ and before the nineteenth century, the phrase to indicate homesickness was ‘maladie du pays’, indicating something closer to physical sickness. In fact, until the twentieth century, homesickness was thought to be a potentially fatal ailment. The medical term for the disease was simply ‘nostalgia’.

In America, not surprisingly, the immigrant population was particularly susceptible to this disease, caused by yearning for the old country. Newpapers reported on individual cases and minor epidemics. An article in the San Francisco Evening Examiner (August 12, 1887) described the demise of one Father J. M. McHale under the headline “Victim of Nostalgia: A Priest Dies Craving for a Sight of His Motherland.”

People who felt sick for home were often advised to avoid experiences likely to trigger nostalgia. Music could be especially dangerous. In his Dictionary of Music, Jean-Jacques Rousseau tells us that at the palace of Versailles in the eighteenth century, it was forbidden to sing or play a tune called “Le Ranz des vaches.” This was because soldiers in the Swiss Guard were deserting their posts after hearing it. The melody was traditionally played on the horn by Swiss herdsmen as they drove their cattle to or from the pasture. When the soldiers heard the familiar mournful tune, some of them were overcome with sadness and longed to return to Switzerland. Others became physically ill with

People who felt sick for home were often advised to avoid experiences likely to trigger nostalgia. Music could be especially dangerous. In his Dictionary of Music, Jean-Jacques Rousseau tells us that at the palace of Versailles in the eighteenth century, it was forbidden to sing or play a tune called “Le Ranz des vaches.” This was because soldiers in the Swiss Guard were deserting their posts after hearing it. The melody was traditionally played on the horn by Swiss herdsmen as they drove their cattle to or from the pasture. When the soldiers heard the familiar mournful tune, some of them were overcome with sadness and longed to return to Switzerland. Others became physically ill with  the dreaded ‘maladie du pays’, while still others simply abandoned their posts and went home. Perhaps, looking out over the perfectly tended gardens of Versailles, they yearned for a more natural landscape.

the dreaded ‘maladie du pays’, while still others simply abandoned their posts and went home. Perhaps, looking out over the perfectly tended gardens of Versailles, they yearned for a more natural landscape.

Here is a link to “Le Ranz des vaches” on youtube. Judging from some of the comments, it still has the power to provoke homesickness. If you are Swiss and living abroad, be forewarned!

May 15, 2015

Why Caucasian is a Dirty Word

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

When a form requires that I identify my “ethnicity” and offers a “Caucasian” checkbox, I make a point of checking “Other” (and writing “White”, where that option exists). Some pollsters have reacted with confusion at my insistence and pointed out that it means the same thing. Like Romeo, they object: “What’s in a name?”

In the case of “Caucasian”, quite a lot.

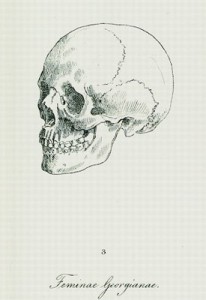

The perfect skull

The term “Caucasian” was first used by Christoph Meiners in 1785, but it was broadly legitimized and popularized by the doctor and early advocate of craniometry, Johan Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840). Blumenbach argued firmly that all humans were of the same species (a contested notion at the turn of the nineteenth century), but divided the human species into five main types, based on skin color and on measurements of the skulls in his collection. Although he believed that all five types had the potential for comparable achievement, he did consider the four non-white types to be degenerated forms of white humans. He called the white type “Caucasian” because the most beautiful, symmetrical skull in his collection was that of a Georgian female, from the Southern slope of the Caucasus.

To many champions of scientistic racism in the nineteenth century, Blumenbach’s medical anthropology became the foundation for arguments of white supremacy. The term “Caucasian” and the notion of a “pure” origin undergirded the claim to the elevated status of white humans.

Quite aside from the arbitrary association with the Caucasus Mountains, posited in 1795, the historical connotations of the term are fundamentally racist, implicitly associating whiteness with superiority.

Skin-deep

Yet does the origin of the term really matter? Historical background notwithstanding, the meaning of the word has changed in the intervening centuries (my harried pollster might cry). After all, very few people who use the term are aware of its history: today, “Caucasian” is just a synonym for white-skinned. So, why the quibbling?

Here, more recent history is illustrative. Since the 1980s, “Caucasian” has come to be used as a genteel, slightly embarrassed companion to the term “African American.” The history of the term “African American” is comparably complex and much more contested, but the term is also frequently used as a euphemism, for all black-skinned people, including those who identify as neither American nor African (as a mistaken characterization of the Dominican baseball player, David Ortiz, for example). Unlike with the term “African American,” however, there has never been a claim to a distinct “Caucasian” culture or history (pace Stuff White People Like). In that regard, “Caucasian” betrays the euphemistic nature of the most common use of both terms in bureaucratic contexts, which is as a label of appearance.

Not only does this euphemism mask the superficiality of the category (why not just write “white” or “black” if it is a question about skin color?), but it also endows the category of ethnicity with a false legitimacy. Race is real, but it is fueled by perception, not genetics. Its most substantive consequences have had much more to do with social beliefs than geographical origin (actual or invented, like the Caucasus Mountains).

—-

I first learned about the history of the term “Caucasian” during an undergraduate lecture at the University of Cambridge by the perspicacious and kind Michael O’Brien (1948-2015).

For more on Blumenbach and the history of the word, see:

Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (W.W. Norton, 2010)

Raj Bhopal, “The beautiful skull and Blumenbach’s errors: the birth of the scientific concept of race” BMJ 2007; 335: 1308