Holly Tucker's Blog, page 29

July 1, 2015

Harvesting Bones at Waterloo

By Gareth Glover (Guest Contributor)

The 18th of June 2015 marks the two hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, which ended the career of Napoleon Bonaparte and brought relative peace to Europe for nearly a hundred years. But the human cost in the short campaign was very severe, with it is estimated over 20,000 dead and over 15,000 horses having to be destroyed as well. Carnage on such a vast scale caused huge problems and whilst the horses were burnt in huge pyres, the bodies of the soldiers were buried in mass graves, so shallow that visitors to the battlefield reported on the sponginess of the soil and that occasionally hands or feet were still visible above the soil!

The 18th of June 2015 marks the two hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, which ended the career of Napoleon Bonaparte and brought relative peace to Europe for nearly a hundred years. But the human cost in the short campaign was very severe, with it is estimated over 20,000 dead and over 15,000 horses having to be destroyed as well. Carnage on such a vast scale caused huge problems and whilst the horses were burnt in huge pyres, the bodies of the soldiers were buried in mass graves, so shallow that visitors to the battlefield reported on the sponginess of the soil and that occasionally hands or feet were still visible above the soil!

Even before they were buried, all the bodies were stripped of any valuables and clothing, making it impossible to identify friend from foe, all shared the same fate. But during the first days after the battle, other visitors arrived to remove other less obvious valuables from the corpses awaiting burial: their teeth! With the introduction of sugar into Europe and with poor understanding of the need to clean teeth, tooth decay was rife, with most over the age of thirty requiring numerous tooth extractions and therefore dentures to hide the damage. Teeth had regularly been supplied by the body snatchers, but these teeth were often already in a poor state when removed from the corpses.

A better source of good quality teeth was from the young men killed in battle and so many were collected at Waterloo that they were carted away in huge oak barrels. Indeed for many years afterwards, dentures were referred to as ‘Waterloo teeth’, although the practice of collecting them continued until after the American Civil War.

Once finally buried, their bones could not rest in peace! In the early nineteenth century it was discovered that bone was an excellent fertilizer and the great battlefields of Europe were dug up to extract the bones so that they could be ground up.

Once finally buried, their bones could not rest in peace! In the early nineteenth century it was discovered that bone was an excellent fertilizer and the great battlefields of Europe were dug up to extract the bones so that they could be ground up.

In 1822 a correspondent wrote that it was now clearly established that a dead soldier was worth more than a live one. He also pointed out that the farmers of Yorkshire were probably enjoying bumper crops with the very bones of their own sons.

For this reason, only one skeleton has been discovered on the battlefield over the last two hundred years, which was recently identified by this author as Private Friedrich Brandt of the King’s German Legion, a German unit in the British Army who died on 18 June 1815 but was buried alone by his colleagues and therefore was probably missed by the bone hunters.

Gareth Glover is an ex Royal Navy officer who has studied the Napoleonic Wars for some forty years. He is renowned as an expert on the archival material on the Battle of Waterloo and has published 6 volumes of this material entitled “The Waterloo Archive”, the new evidence from which has caused him to rewrite the history of the battle in ‘Waterloo, Myth & Reality’ and present his findings to a new audience in ‘Waterloo in 100 Objects’.

Gareth Glover is an ex Royal Navy officer who has studied the Napoleonic Wars for some forty years. He is renowned as an expert on the archival material on the Battle of Waterloo and has published 6 volumes of this material entitled “The Waterloo Archive”, the new evidence from which has caused him to rewrite the history of the battle in ‘Waterloo, Myth & Reality’ and present his findings to a new audience in ‘Waterloo in 100 Objects’.

June 30, 2015

Picturing Syphilis

By Maureen Gibbon (Guest Contributor)

My novel Paris Red is a fictional account of the relationship between artist Édouard Manet and his favorite redheaded model, Victorine Meurent, the woman who posed for Olympia and Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe. Since Manet died from the effects of untreated tertiary syphilis when he was fifty-one, it was important to me to understand something about the disease.

Syphilis was so widespread in the nineteenth century that one French syphilologist estimated 13 percent of Parisians were infected. Odds got better in New York City, where public health records indicate 5 percent of New Yorkers were syphilitic.

Syphilis was so widespread in the nineteenth century that one French syphilologist estimated 13 percent of Parisians were infected. Odds got better in New York City, where public health records indicate 5 percent of New Yorkers were syphilitic.

Some of the individuals making up that New York statistic may have been patients of Manhattan doctor George Henry Fox and the unwitting stars of his pioneering 1881 book of medical photographs, Photographic Illustrations of Cutaneous Syphilis.

Even though the book features portraits of New Yorkers and not Parisians, it helped me picture the disease that affected Manet. In addition, George Henry Fox had his own Paris connection: in 1872 he studied at l’Hôpital Saint-Louis with Alfred Hardy, editor of the first medical journal to use photographs. Perhaps Fox passed Manet on the street one day.

Back in America, Fox learned to visually diagnose his patients at the Northwestern Dispensary, a medical facility for New Yorkers who could not afford private doctors. He believed so vehemently that photography could aid physicians that he declared, “The study of skin diseases without cases or colored plates is like…the study of geography without the maps.”

Fox had to rely on commercial photographers like E. K. Hough, who had a studio around the corner at 487 Eighth Avenue, or borrow photos from others involved with medical photography, like Oscar G. Mason, also known as O.G. Mason, the medical photographer at Bellevue Hospital. After amassing a collection of vivid images, Fox decided to display the best at the office of the Medical Journal Association.

Fox had to rely on commercial photographers like E. K. Hough, who had a studio around the corner at 487 Eighth Avenue, or borrow photos from others involved with medical photography, like Oscar G. Mason, also known as O.G. Mason, the medical photographer at Bellevue Hospital. After amassing a collection of vivid images, Fox decided to display the best at the office of the Medical Journal Association.

That’s where publisher E. B. Treat saw the show. Treat invited Fox to put his photographs together for publication in what turned out to be two volumes: Photographic Illustrations of Skin Diseases, first published in 1880, and Photographic Illustrations of Cutaneous Syphilis, published in 1881.

Fox was democratic in his beliefs about syphilis, stating that the disease was universal, occurring “in every rank of society, from the prince to the pauper.” Yet he probably wasn’t treating princes at the Northwestern Dispensary, located at 511 Eighth Avenue. The Northwestern and other New York City dispensaries relied on a combination of city, state and private monies, and they operated so close to their bottom lines that they sometimes ran out of containers for medicine.

In addition to aiding me in my understanding of the disease, I used several photos from Fox’s book as inspiration for characters in Paris Red, including the highly perfumed “jasmine woman.” Fox helped me see an intimate part of life in the nineteenth century.

Maureen Gibbon is the author of the novels Paris Red, Thief and Swimming Sweet Arrow. Visit www.maureengibbon.com to learn more.

Maureen Gibbon is the author of the novels Paris Red, Thief and Swimming Sweet Arrow. Visit www.maureengibbon.com to learn more.

W&M is excited to have one (1) Hardcover copy of Paris Red and one digital download for an Audio version of Paris Red in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on July 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

June 27, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: On Pins and Needles and High Heels

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

From helmets, to hairstyles, to high heels, style over the centuries is about so much more than function. This week we are taking a look at some intriguing reads about style history, quite literally from head to toe.

Head over Heels

Head over Heels

As history buffs we are quite familiar with the work of archaeologists, but what about a hairdo archaeologist? Janet Stephens, a hairdresser, found herself taking this unusual path when she became enamored with images of intricate ancient Greek and Roman hairstyles. Other experts believed these must be wigs, but Janet used her research, both historical and practical to show that these elaborate hairstyles were possible with a person’s hair when using a sewing technique. Read all about the fascinating research journey of this hairdresser turned published historian. You can even watch some of Janet’s YouTube videos that show how she recreates the ancient hairstyles, like this one featuring the hair of Rome’s Vestal Virgins.

Women may have adorned their heads with intricate hairstyles for centuries, but men also adorned their heads: with helmets. More than just functional, Ancient and Medieval helmets were also a beautiful expression of culture. From simple and functional to elaborately carved, a recent article aptly titled A Head for War gives us a look at some of the most impressive head protection. My personal favorite is the Mycenaean helmet made entirely of boar’s tusk (pictured left), but the Murmillo Gladiator helmet embossed with battle scenes is also a sight to behold.

Women may have adorned their heads with intricate hairstyles for centuries, but men also adorned their heads: with helmets. More than just functional, Ancient and Medieval helmets were also a beautiful expression of culture. From simple and functional to elaborately carved, a recent article aptly titled A Head for War gives us a look at some of the most impressive head protection. My personal favorite is the Mycenaean helmet made entirely of boar’s tusk (pictured left), but the Murmillo Gladiator helmet embossed with battle scenes is also a sight to behold.

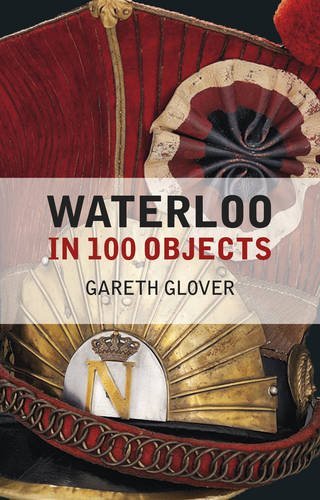

The Agony of Being Well-heeled

Like the helmet, shoes were conceived as a way to protect fragile human bodies, in this case the feet. Over the time this form of protection actually inflicted more pain in the name of style. In “The History of Shoes Has Been Frivolous, Ridiculous and Extreme” we learn about the lengths, or rather heights, people will go to for the sake of fashionable feet. The article highlights some of the more extreme shoes men and women have subjected their feet to, including the chopine a 16th century Venetian platform, that isn’t too different from many platform shoes seen on the runways today (pictured right).

Like the helmet, shoes were conceived as a way to protect fragile human bodies, in this case the feet. Over the time this form of protection actually inflicted more pain in the name of style. In “The History of Shoes Has Been Frivolous, Ridiculous and Extreme” we learn about the lengths, or rather heights, people will go to for the sake of fashionable feet. The article highlights some of the more extreme shoes men and women have subjected their feet to, including the chopine a 16th century Venetian platform, that isn’t too different from many platform shoes seen on the runways today (pictured right).

For even more on the extreme nature of sole style, take a look at London’s Victoria and Albert Gallery new exhibit Shoes: Pleasure and Pain. If you’re in London, this unique exhibit arranged around the effect shoes make, such as status or height, is worth a visit. If you can’t make the jaunt in person, or your feet are just to sore to traipse about London, take a look at the virtual presentation the museum offers.

Wishing you had more to read? No problem! Check out these recent posts:

The Unheraled Co-Author of “The Count of Monte Cristo”

What Happened to the Hanging Garden of Babylon?

June 25, 2015

Childbirth as a Spectator Sport

By Catherine Delors (Guest Contributor)

At Versailles, not only the Queen, but princesses of the royal blood were required to give birth in public. Why? To prevent any substitution of the infant in case he was destined to reign. I say “he” by design, because France’s unwritten constitution prevented women to step unto the throne in their own right, though they could, and often did govern the Kingdom as Regents.

Marie-Antoinette’s First Laying In

In the case of Marie-Antoinette, her first laying-in was all the more eagerly awaited that she had been married for eight years without presenting her husband with an heir. For a Queen, this was a glaring failure. Her sister-in-law, the Comtesse d’Artois, married to the King’s youngest brother, had already been delivered of two healthy little boys. Marie-Antoinette had attended the deliveries, as required by the etiquette, and deeply felt the political and personal humiliation of her own childlessness.

Now at long last she herself was pregnant. The stakes could not be higher: if the child were stillborn, or a girl, the heir to the throne would remain the Comte de Provence, another brother of Louis XVI. The Comte de Provence was cunning, ambitious, and probably the most dangerous enemy of the royal couple. Every year that passed without Marie-Antoinette giving birth to a Dauphin brought him closer to the throne (to which he would eventually ascend, decades later, under the name of Louis XVIII.)

Let us listen to what Madame Campan, First Chambermaid to Marie-Antoinette, tells us in her irreplaceable Memoirs: “The Queen’s laying-in approached; Te Deums were sung and prayers offered up in all the cathedrals. On December 11, 1778, the royal family, the Princes of the royal blood, and the Great Officers of State spent the night in the rooms adjoining the Queen’s Bedchamber.” This, by the way, was days ahead of time because the child would not be born until the 19th of December.

Finally, before noon, it became certain that the birth was imminent. “The etiquette,” continues Madame Campan, “allowing all persons indiscriminately to enter at the moment of the delivery of a queen was observed with such exaggeration that when the obstetrician said aloud: “The Queen is going to give birth!” the persons who poured into the chamber were so numerous that the rush nearly killed the Queen. During the night the King had taken the precaution to have the enormous tapestry screens which surrounded Her Majesty’s bed secured with cords; but for this they certainly would have been thrown down upon her. It was impossible to move about the chamber, which was filled with so motley a crowd that one might have fancied himself in some place of public amusement. Two chimney-sweeps climbed upon the furniture for a better sight of the Queen.”

Marie-Antoinette fainted. Was it simply pain? The body heat created by the crowd packed in the bechamber? The feeling of being exposed to strange eyes in a circus scene? Or the pressure to give birth to a boy? Apparently Marie-Antoinette and her friend the Princesse de Lamballe, Head of the Queen’s Household and member of the royal family, had agreed on a sign the Princesse would make to inform Marie-Antoinette of the child’s gender as soon as it became apparent. Normally that announcement would have been made more formally minutes later, and Marie-Antoinette wanted to know right away. And the child turned out to be a girl! Maybe the disappointment was enough to make the Queen lose consciousness.

The obstetrician decided that the patient needed to be bled (indeed what patient wasn’t in need of a good bloodletting in the 18th century?). More sensibly by modern standards, he called for the windows to be opened wide.

The King sprung to action. The windows had been stopped up (Versailles has always been notoriously drafty) and he rushed to force them open. Let us not forget that Louis XVI was a man of unusual height and strength.

The Court’s head surgeon then seized his lancet and bled the Queen. Whether thanks to his ministrations or more likely the rush of fresh air in the stifling room, she opened her eyes. At this moment the Princesse de Lamballe, who was much given to what was then called “nervous spasms,” added to the general confusion by fainting herself. She had to be carried through the crowd “in a state of insensibility.” Only then was it deemed necessary to empty the room of all idle onlookers. “The valets,” writes Madame Campan, “dragged out by the collar such inconsiderate persons as would not leave the room.”

“This cruel custom,” continues Madame Campan, “was abolished afterwards. The Princes of the family, the Princes of the blood, the Chancellor, and the ministers are surely sufficient to attest the legitimacy of a prince.”

Certainly it was an improvement, but that still left a few dozen people to attend every royal birth…

Catherine Delors is author of Mistress of the Revolution. She also keeps a fascinating blog on all things royal during the eighteenth century.

Catherine Delors is author of Mistress of the Revolution. She also keeps a fascinating blog on all things royal during the eighteenth century.

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in March 2009.

June 23, 2015

Prognosticating the Past

By Nancy Goldstone (Guest Contributor)

Nostradamus, the celebrated sixteenth century prophet, has a reputation that any modern day pollster, hedge fund manager, or bookie would envy. His mysterious verses have been credited with predicting an astonishing array of future events, including 9/11 and the death of Princess Diana. Only the Arthurian Merlin, (who had the unsporting advantage of being a wizard and living backward) could claim a better record for infallibility.

Catherine de Medici

But how accurate were Nostradamus’s forecasts in his own lifetime, and what was the effect of having so great a seer available for private consultation on the landmark developments of the day? To answer these questions it is necessary to examine the influence of Catherine de’ Medici, queen mother of France, amateur occult enthusiast, and Nostradamus’s most important sponsor, on the great man’s body of work.

It is not an exaggeration to say that without Catherine, Nostradamus’s famous prognostications might well have been consigned to the dustbin of history. It was she who plucked him from obscurity, singling him out from the multitude of other would-be soothsayers gripped by visions (medication was not an option in the sixteenth century); she who dragged some eight hundred members of the royal court all the way from Paris to Nostradamus’s home in Provence so that she could question him directly and hear the wisdom of the ages from his own lips; she who acted upon and broadcast his augurs to her fellow sovereigns around the world, thus ensuring his enduring celebrity.

And of course, the queen mother of France wasn’t much interested in the tragic car accident that would take the life of the divorced wife of the Prince of Wales five hundred years in the future. Catherine wanted to know what was going to happen now—or rather, then. So he told her.

He told her that her fourteen-year-old son Charles IX, king of France, would marry Elizabeth I, seventeen years his senior, and live to be ninety. Elizabeth I demurred, and Charles died at twenty-four.

He told her that in two years there would be world peace, and that the kingdom of France would be particularly tranquil. The Netherlands rebelled against the Spanish, prompting a bloody conflict that involved most of Europe. At the same time, horrific violence between Protestants and Catholics, known as the Wars of Religion, broke out in France.

He told her that all four of her sons would be kings, a prophecy that drove Catherine’s foreign policy. Yet her youngest still went to his deathbed only a duke.

Luckily for him, Nostradamus died soon after making these predictions, so he never had to explain what went wrong. Judging by his experience, it would seem that accuracy in the past has very little to do with renown in the future!

Nancy Goldstone‘s latest book, The Rival Queens: Catherine de’ Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois, and the Betrayal That Ignited a Kingdom, will be published in June by Little, Brown and Company.

Nancy Goldstone‘s latest book, The Rival Queens: Catherine de’ Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois, and the Betrayal That Ignited a Kingdom, will be published in June by Little, Brown and Company.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of The Rival Queens in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”

Laura J. Snyder, “Eye of the Beholder”

Stephanie Dalley, “The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon”

June 22, 2015

Blown Away: The Mongol Invasions of Japan

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

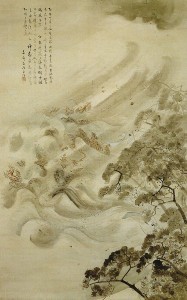

Mongol fleet destroyed in a typhoon, Kicuchi Yosai, 1847

Japan had expected the Mongol invasion for years.

In 1266, Kublai Khan, the new Mongol emperor of China, sent envoys to Japan with a letter addressed to the “King of Japan”–a title guaranteed to offend the Japanese emperor. The letter itself was equally unpalatable. The Great Khan “invited” Japan to send envoys to the Mongol court in order to establish friendly relations between the two states–code for the tributary relationship China habitually imposed on its neighbors. The letter ended with an implicit threat: “Nobody would wish to resort to arms.” Both the largely symbolic imperial court at Kyoto and the military government at Kamakura, which had controlled Japan since the late twelfth century, chose to ignore the khan’s overtures.

For several years Kublai Khan was distracted by more immediate concerns: subduing the newly conquered province of Korea and his war against the Song dynasty of southern China. It was 1274 before the Mongol emperor turned his attention to Japan once more. On November 2, a fleet of 900 ships sailed from Korea with over 40,000 men, including Chinese, Jurchen, and Korean soldiers and a corps of 5,000 Mongolian horsemen. The invasion forces landed first at the islands of Tsushima and Iki, where the local samurai were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of their attackers.

With the intervening islands secured, the Mongols moved on to the Japanese mainland, landing at Hakata Bay on November 19. The Japanese were waiting for them, alerted by the news from Tsushima and Iki. When the Mongols landed, the twelve-year-old grandson of the Japanese commander-in-chief fired the shot that was the traditional opening in a samurai battle: a signaling arrow with a perforated wooden head that whistled as it flew to draw the attention of the gods to the deeds of bravery about to be performed. The Mongols responded with raucous laughter.

It was an omen of how the day’s battle would proceed. Both armies depended on their archers, but their fighting styles were dramatically different. The Japanese were accustomed to fighting in small-group or individual combat, seeking out worthy opponents by shouting a verbal challenge. They fired single arrows aimed at specific targets. The Mongols advanced in tightly knit formations and fired their arrows in huge volleys. Their movements were accompanied by roaring drums and gongs, which frightened the Japanese horses and made them difficult to control. When the Mongol forces pulled back, they fired paper bombs and iron balls that exploded at the samurais’ feet–something the Japanese had not seen before.

Seriously outnumbered and baffled by the invaders’ tactics, the Japanese were not able to hold the beaches. By nightfall, they had retreated several miles inland. Instead of pressing forward, the Mongolian forces returned to their ships for the night. A successful attack the next day seemed inevitable, but that evening an unseasonable storm struck the Mongol fleet, dashing its ships against the rocks. With their ships smashed and about one-third of their force dead, the Mongols withdrew. The Japanese hailed the storm as a divine wind (kamikaze), sent by the gods to protect them.

Seven years later, Kublai Khan tried again. The Mongols launched a two-pronged attack against Japan, with a combined fleet of almost 4,000 ships and 140,000 men. The Eastern Army sailed from Korea on May 22; the Southern Army sailed from southern China on July 5. The two fleets were to meet at Iki and proceed together against mainland Japan. The Eastern Army subdued Tsushima and Iki in early June. Instead of waiting for the Southern Army to arrive, they moved on to Hakata Bay.

Japan had used the intervening years to build earth and stone fortifications along the coast of Hakata Bay. When the Mongols arrived, Japanese defenders repulsed the attack from a secure position behind the defensive walls. When the Mongols retreated, the Japanese took the war to them, using small boats to attack the Mongosl at night. After a week of fierce fighting, the Eastern Army retreated to Iki Island to await the arrival of the Southern Army.

The two Mongol forces rendezvoused in early August. On the evening of August 12, the Japanese attacked, using the “little ships” tactic that had been successful before. The Mongols responded by linking their ships together to create a defensive platform. The battle continued through the night. At dawn, the exhausted Japanese retreated, expecting a decisive attack and the subsequent invasion of the mainland. Instead the Mongol ships, still linked together, were caught in a typhoon that dashed the ships against each other and the shore. When the typhoon subsided, the surviving ships headed out to sea, leaving thousands of stranded soldiers behind them to be massacred by the Japanese.

Japanese chroniclers cited the winds as proof that the gods themselves protected the island. The idea of “divine winds” (kamikaze) that protected Japan against invasion remained an important element in Japanese political mythology as late as the Second World War.

June 20, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Ancient Animal Tales

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

When tracing the history of mankind, we inevitably find the history of other animals intertwined with our own. This week we are highlighting stories about how man and animal changed each other’s course of history.

Fluffy Bunnies Responsible for Early Man’s Downfall?

Fluffy Bunnies Responsible for Early Man’s Downfall?

Scientists may finally have the answer to why Neanderthal’s became extinct: the rabbit. Well, the rabbits, who were quite plentiful at the time, are actually just a clue about the Neanderthal’s demise. Neanderthal’s didn’t feast on these fluffy friends, not because of their adorable long ears, but because they couldn’t catch these quick, hopping prey. Read why this was so problematic in the study from Bournemouth University.

Feline Mummies, Canine Catacombs, and Elite Pets

If you have felt sorry for those mummified cats that were mummified with their Egyptian owners, this story will lay some of your worries to rest. Recent scans of mummified cats and birds at the Manchester Museum reveal that there are no skeletal remains in about a third of these mummified animals. Instead of true mummies, these are more like offerings that Egyptians purchased.

But before all the animal lovers rejoice too much, we must tell you that another recent story on the canine catacombs of Ancient Egypt has a less comforting conclusion. Approximately 8 million mummies of dogs and jackals sacrificed to the jackal-headed god Anubis have been found in tunnels in the ancient capital of Memphis. Even more disturbing for modern dog lovers is that many appear to be puppies bred purely for sacrificial purposes.

But before all the animal lovers rejoice too much, we must tell you that another recent story on the canine catacombs of Ancient Egypt has a less comforting conclusion. Approximately 8 million mummies of dogs and jackals sacrificed to the jackal-headed god Anubis have been found in tunnels in the ancient capital of Memphis. Even more disturbing for modern dog lovers is that many appear to be puppies bred purely for sacrificial purposes.

Domestic dogs and cats weren’t the only ones who suffered due to the social and religious mores. Skeletons of so called “elite pets”, such as baboons and elephants, which demonstrated power and wealth in Egyptian society show evidence of beatings and injuries. As sad as these findings are, later skeletons and mummified remains of baboons that do not show signs of mistreatment illustrate that Egyptians did learn how to subdue and keep these “pets” more humanely over time without harsh beatings.

Stork Tales

We cannot end our post on such a sad note, so we bring you one last  story that may help restore your faith in man’s relationship with animals. Bulgarian archaeologists have discovered the oldest toy known to man, a late bronze age Thracian toy stork. Though not sure of its use, this bronze and silver stork with carnelian eyes does show early appreciation of the animals beauty and form. The simple little stork even has a head that can be made to “drink water”.

story that may help restore your faith in man’s relationship with animals. Bulgarian archaeologists have discovered the oldest toy known to man, a late bronze age Thracian toy stork. Though not sure of its use, this bronze and silver stork with carnelian eyes does show early appreciation of the animals beauty and form. The simple little stork even has a head that can be made to “drink water”.

If you are looking for more on ancient or animal history, check out these recent posts on Wonders & Marvels:

Feeling Swinish: Or the Origins of a Pandemic

Roman Fascination with Amazons

June 19, 2015

Cultural Amnesia

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

I had originally prepared a different piece for this month, on silent cinema and amnesia, but it feels somehow inappropriate to post it today into an internet-media world awash with reactions to the violent act of terror committed in Charleston, SC. I lack the expertise to write on the cruel history of attacks on the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the complex meaning of the Confederate flag or the flaws of US media coverage. As a European living in the South, however, I do have a personal response to the slightly relieved distance with which Europeans describe racism and its history in the US South: namely, discomfort at the cultural amnesia about European history that sense of distance betrays.

Antebellum Tourism

When I first visited Charleston, SC in 2012 (my first visit south of the Mason-Dixon line), I was equally guilty of this presumed cultural innocence. I quietly upbraided the house tours which failed to recognize either the contributions of enslaved builders and servants or the cruel source of the wealth that funded them, and remember being particularly piqued that the preserved plantation house Drayton Hall offered a separate, unsubscribed African-American history tour rather than including that history in the default tour every visitor took. It seemed deeply problematic that the romance of the antebellum South could be celebrated by tourists without inextricable reminders of the exploitation that undergirded it, or of the history of alternative cultures which emerged away from the white elite.

After sharing this observation with a few friends, however, I thought back to earlier visits to Liverpool and Bristol, both built –like Charleston—almost entirely on wealth generated by the slave trade. Neither they, nor areas of London financed by imperial wealth like Knightsbridge, counter their architectural grandeur with frank reflections on the vast human costs of the economies that financed them. Certainly not to the extent that I demanded of Charleston when I visited. Which is not to say that the presentation of antebellum history in the South is unproblematic, but rather that Europeans should hold themselves to the same standards. As should those who curate the history of the US North: I don’t remember much discussion of African American history at the New England Cotton Mills I visited either, for example.

A Retreat from Triumphalism?

The reason this matters is that self-awareness could prevent the subtle, almost imperceptible triumphalism that such condescension to the US South sometimes masks. Pride in the new South does not necessarily equate to nostalgia for the old South, or with racism, but the refusal of outsiders to recognize this nuance can lead white Southerners to mistakenly cling to hateful symbols like the confederate flag that only tear at multiple wounds. In short, racist violence is not just a Southern problem, and it does not serve the women and men who were murdered on Wednesday to indulge in any shade of self-righteous distancing.

[Next month, I will retreat from personal opinion and return to carefully researched topics in the European history of medicine, science, film, photography and war.]

June 18, 2015

The Dangers of a Mycenaean Childhood

By Katharine Beutner (Guest Contributor)

My novel narrates the life of a Mycenaean queen named Alcestis, who is famed for choosing to die in her husband’s place. Most versions of her story say nothing about her time in the underworld. When I began my novel, I knew that Alcestis needed something to drive her exploration of the underworld—something, or someone, to search for. Callous as it sounds, I had to kill someone she loved.

As a young princess of Iolcus, Alcestis spends nearly all of her time in the women’s quarters with her two older sisters. The middle sister, Hippothoe, cares for Alcestis after their mother dies giving birth to her. I needed to find an illness to inflict upon poor gentle Hippothoe, and I wanted that illness to be familiar enough to modern readers that they would instantly recognize its dangers.

As a young princess of Iolcus, Alcestis spends nearly all of her time in the women’s quarters with her two older sisters. The middle sister, Hippothoe, cares for Alcestis after their mother dies giving birth to her. I needed to find an illness to inflict upon poor gentle Hippothoe, and I wanted that illness to be familiar enough to modern readers that they would instantly recognize its dangers.

The first usage of the word “asthma” (άσδμά) occurs in the Iliad, where it refers to a short inhalation—the word derives from the Greek infinitive “aazein.” Classical-era Greek physicians describe the symptoms we now know as asthma, and there’s some evidence that the Egyptians also recognized it as a distinct disease.

I researched contemporary homeopathic remedies for asthma to find methods that might have been available to the Mycenaeans and settled on two liquid remedies: diluted honey and garlic tea. As an adult, Alcestis remembers Hippothoe’s garlic-and-honey smell and recalls going to the kitchens in the middle of the night to prop her sister up over a steaming kettle. Modern readers who have suffered from asthma or watched a family member or friend struggle to breathe will understand the helpless frustration Alcestis feels as she watches her sister endure an asthmatic attack. Even now, with our remarkable advances in medical treatment, the human experience of illness connects us to the Bronze Age.

Katharine Beutner‘s debut novel, Alcestis, has just been published by Soho Press. She holds an MA in fiction from the University of Texas at Austin, where she is now a doctoral candidate in English literature.

IMAGE: Hercules Fighting Death to Save Alcestis, By Frederic Lord Leighton, c 1869-71

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in February 2010.

June 16, 2015

The Unheralded Co-Author of “The Count of Monte Cristo”

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

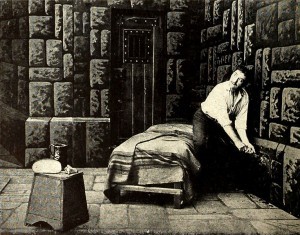

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas appears on many lists of the greatest novels, and twice I have attempted to read it. The first time, about ten years ago, I devoured the opening third of the book, which covers the framing and unjust imprisonment of young Edmond Dantès on charges of treason against the post-Bonapartist French government of 1815, along with his exciting and elaborately planned escape from confinement. I ran into trouble during the remainder of the book, however, which concerns Dantès’s efforts to exact revenge upon the people who sent him to prison. The hero’s search for vengeance struck me as sour, predictable, and unworthy of the man who so cleverly and bravely had foiled his jailers, and I gave up the book half-way through.

James O’Neill as Edmond Dantès in the 1913 silent film adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo

Three years ago, I again tried reading The Count of Monte Cristo. This time I made it to the end of the book, but again I found the concluding half far less engaging than the opening. It seemed as if two different authors had written this novel: one who told a tale of spellbinding adventure, and a second who wrote turgidly of the angst of a damaged and unappealing man.

As it happens, some literary scholars now believe that two writers did compose The Count of Monte Cristo (as well as many other works solely credited to Dumas, including The Three Musketeers), although the co-authors did not divide the novel in the way I had envisioned.

Dumas’s collaborator was Auguste Maquet, who was born in Paris in 1813 and received academic training as a historian. Unsuccessful in publishing his own historical novels, Maquet met Dumas in 1838 and began a close literary partnership with the well-known writer that lasted nearly twenty years. Maquet researched history, outlined plots, and sketched characters, while Dumas wrote dialogue, filled in events, provided lovely language and embellishment, and built upon the skeletons that Maquet offered him. Dumas got the byline and recognition; Maquet received a share of the royalties.

Maquet seems to have seen his collaborator as the real genius in the enterprise, and he regarded himself as more of a craftsman. Late in their partnership, Maquet tried to wrest from Dumas public acknowledgment of his contributions, but he failed in court. Several of Maquet’s own novels were published under his name during his life, including such now-forgotten titles as Debts of the Heart, Beautiful Gabrielle, and Madame de Limiers.

Maquet outlived Dumas by eighteen years and died in 1888, but his heirs kept an eye on the royalty statements. During the early years of the twentieth century, family members successfully sued in French court to recover money still owed them from sales of Dumas’s novels.

A film released in 2010, The Other Dumas, stars Gerard Depardieu in an examination of the relationship between Dumas and Maquet.

Further reading:

Dumas, Alexandre (with Auguste Maquet). The Count of Monte Cristo. P.F. Collier, 1846.

Schopp, Claude. Alexandre Dumas: Genius of Life. Franklin Watts, 1988.