Holly Tucker's Blog, page 30

June 16, 2015

What Happened to the Hanging Garden of Babylon?

By Stephanie Dalley (Guest Contributor)

Why could archaeologists not find the site of the fabled Hanging Garden of Babylon beside Nebuchadnezzar’s enormous palace at Babylon? Why did Nebuchadnezzer omit to mention that he had created a world wonder in his complete and detailed inscriptions? Why were the Greek accounts of the Hanging Garden written so many centuries later than the time when it was created?

These are some of the intriguing questions that impelled me to find out how to understand the tradition. Earlier scholars had sometimes despaired of a real historical Wonder, and suggested pure legendary fiction, but that was not satisfactory because all the other ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ were known to have been real monuments – the Egyptian pyramids, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Statue of Zeus of Olympia, and the temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

These are some of the intriguing questions that impelled me to find out how to understand the tradition. Earlier scholars had sometimes despaired of a real historical Wonder, and suggested pure legendary fiction, but that was not satisfactory because all the other ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ were known to have been real monuments – the Egyptian pyramids, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Statue of Zeus of Olympia, and the temple of Artemis at Ephesus.

While working on an inscription of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who reigned a century earlier than Nebuchadnezzar, I began to realize that details of his palace and garden at Nineveh matched some of the extraordinary details of the Hanging Garden described by the later Greek writers, not least the raising of water up the garden high up on the citadel mound, by means of an Archimedean screw long before the lifetime of Archimedes himself. Sennacherib described his palace with its garden as ‘a wonder for all peoples’.

At the top of the garden, Greek writers described a pillared walkway roofed with layers of matting and soil so that trees grew above it. A drawing made in the mid-nineteenth century, of a panel of sculpture now lost, showed just such a pillared walkway at the top of a garden. The drawing is preserved in the British Museum. The original panel was part of an Assyrian palace at Nineveh.

Water was conducted on to the citadel via canals and aqueducts from a gorge in mountains over 90 km away. This remarkable engineering work was studied between the two World Wars, and in recent times has been enriched by tracking from early satellite photos. Alexander the Great would have admired it when he camped nearby with his army before the Battle of Gaugamela. In 2013 I made a documentary for Channel 4 about that aspect of the World Wonder, which has been shown all over the world.

Sennacherib had inherited from his father rule over the city of Babylon, but after his son as regent was abducted by enemies, in his fury he removed the city’s gods to Assyria, so that Nineveh, his capital city, became as if a new ‘Babylon’. When the Assyrian empire came to an end, around 612 BC, Nineveh was not totally destroyed, as Hebrew prophets described with typical literary exaggeration. It continued to be inhabited, rising again to become the great city that Jonah found, and which was well known to historians of the Roman empire.

Stephanie Dalley is an Honorary Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford, a Member of Wolfson College, Oxford, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. With degrees in Assyriology from the Universities of Cambridge and London, her academic career has specialized in the study of ancient cuneiform texts and she has worked on archaeological excavations in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. She has written several books on the myths and culture of ancient Mesopotamia, with special reference to their impact on later civilizations, many of which have been translated into Arabic, Italian, and Japanese.

Stephanie Dalley is an Honorary Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford, a Member of Wolfson College, Oxford, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. With degrees in Assyriology from the Universities of Cambridge and London, her academic career has specialized in the study of ancient cuneiform texts and she has worked on archaeological excavations in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. She has written several books on the myths and culture of ancient Mesopotamia, with special reference to their impact on later civilizations, many of which have been translated into Arabic, Italian, and Japanese.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”

Laura J. Snyder, “Eye of the Beholder”

Stephanie Dalley, “The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon”

June 15, 2015

How to Order a Drink in Latin: Essential Conversation for Travelers

By Elizabeth Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Books about the art of conversation date back to Cicero, who outlined many of the principles that continue to be promoted in etiquette manuals today. Don’t interrupt, do remember people’s names, be sure to listen and be attentive (or at least pretend to be). In Renaissance Europe, conversation books were published that included actual model dialogues, to give readers an idea of how to talk in polite society.

But in the eighteenth century a new kind of conversation book appeared, this one aimed at travelers who just wanted to make themselves understood. The model dialogues in these books were based on practical problems – how to find a room for the night, how to ask for your favorite food at an inn. As early  tourists began to travel more widely, one of the most pressing problems was learning the essential vocabulary of a foreign language. An educated young Englishman doing the ‘Grand Tour’ in the mid-eighteenth century did not typically learn French, German, Italian, or Spanish in school. Nor would a young Frenchman study English, or a Spaniard German. They all studied Latin.

tourists began to travel more widely, one of the most pressing problems was learning the essential vocabulary of a foreign language. An educated young Englishman doing the ‘Grand Tour’ in the mid-eighteenth century did not typically learn French, German, Italian, or Spanish in school. Nor would a young Frenchman study English, or a Spaniard German. They all studied Latin.

So, the earliest conversation manuals published for travelers provided sample conversations in Latin, the common language of educated people. As the author of Le Guide du voyageur put it, his little book would be of use not only to educated travelers, but also to innkeepers, tradesmen, and even “soldiers who find themselves in foreign lands unable to make themselves understood when they ask for the simplest things.”

Here’s a sample of some of the useful topics and phrases provided in the first chapter of this guide, published in 1758:

Here’s a sample of some of the useful topics and phrases provided in the first chapter of this guide, published in 1758:

Arriving at the Inn

Innkeeper, do you have good beds? We do not want to feel any fleas or lice. Heus, suntne in diversorio tuo lecti molles? Pulices, cimicesque aversamur.

Have our pistols and trunks taken to our room; and bring us the wine to taste. Jube saccos saccinarios atque sclopetos ad cubile nostrum; & vinum nobis ministrari.

Will we find carriages to rent nearby? Suntne in proxime rhedae conducticiae?

At Supper

What do you think of this wine? Quid tibi hoc vinum placet?

These pigeons are big and fat: take a whole one. Columbi isti sunt corpulenti & pingues: unum ex iis ministra tibi.

No, I’ll give half to my neighbor, pass your plate. Minime, dimidiam partem vicino meo praebebo: orbem porrigere velis.

Taste these sausages. Ede ex istis botellis.

Is this a rabbit pâté? Estne confectum ex lepore?

In Case of Illness

I had a very bad night; I had a fever; I ache all over. Inquietam noctem egi; febri laboravi; dolent universae corporis partes.

You will need to take a remedy. Have you been bled? Clysteribus ciendus est alvus. Justissine sanguinem tibi detrahi?

Departure

Is the road nice? Plana est ne via? Is the road dangerous? Via est ne tuta ab insidis? Do they say there are robbers in the woods? Rumor est latrones in saltu pervagari?

Where is my whip? Ubinam est flagellum meum?

Other sections cover such topics as conversation on a promenade, shopping for meat, discussing the weather, getting good quills and paper for writing letters, getting a shave, caring for horses, playing cards, getting your boots cleaned, and (repeatedly) eating and drinking.

I wonder if these books were ever used as conversation manuals for pupils learning Latin. I understand that current education reforms underway in France are likely to eliminate Latin from the high school curriculum. Maybe Le Guide du voyageur should be put back into circulation!

I wonder if these books were ever used as conversation manuals for pupils learning Latin. I understand that current education reforms underway in France are likely to eliminate Latin from the high school curriculum. Maybe Le Guide du voyageur should be put back into circulation!

For further reading: Le Guide du voyageur, ou, dialogues en français et en latin. A l’usage des militaires et des personnes qui voyagent dans les pays étrangers. Paris: Guillyn, 1758.

June 12, 2015

Storms of the Past: The Making of Modern Meteorology

By Peter Moore (Guest Contributor)

Sketch by Thomas Forster

In the year 1800 the sky remained an unknowable blue wilderness. No one knew how far up the atmosphere went or how clouds remained suspended in the air. People had not explained how a storm operated or where dew came from or why the sky was blue. In all, meteorology remained a strange and obscure science, little advanced from the time of Aristotle and his concept of “meteors”.

Yet in just seventy years there was a revolution in the subject. Once so fraught with mystery that it was considered by many to be the graveyard of a philosophic reputation, in a few decades meteorology reinvented itself as a modern science. In 1803 names were assigned to the clouds for the first time by Luke Howard, a London chemist. In 1806 a sailor called Francis Beaufort jotted down a quantifiable scale for wind which has survived to this day.

In America theorists like William C. Redfield and James P. Espy developed revolutionary new ideas to explain the movement of storms up the vulnerable eastern coast. By the 1840s all these ideas were knitted together by a revolutionary new technology: Samuel Morse’s Electo-Magnetic Telegraph. Soon meteorology was in vogue. In London John Ruskin wrote that the science was “full of the soul of the beautiful”.

This book tells the stories of the little, individual experiments. There is John Constable, the landscape painter, on Hampstead Heath straining to sketch the passing clouds. There is James Espy in Fairfax County, Virginia, setting fire to a pine forest in a bid to make rain. Out in the grounds of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, a young scientist called James Glaisher lies flat in the grass at night measuring the growth of a drop of dew.

A Map of Air Masses from The Weather Book by Robert Fitzoy

Meanwhile in the Caribbean Islands a man watches as the atmosphere shifts. The skies have turned a fierce, lurid red. Olive clouds scud overhead, a swell stirs in the harbour, the breeze freshens. He watches his barometer dip. A storm is on its way.

These are the little experiments. And drawn together they combine to create what I had come to think of as a generational experiment. The hypothesis of this might be: “That the atmosphere is not chaotic beyond understanding, that it can be measured and understood and even predicted.” This, therefore, becomes “The Weather Experiment” and prediction is at the heart of the story as it became one of the dilemmas of the age.

If a scientist knows that a storm – or worse – is on the way, then do they not have a duty to warn people? This scientific conundrum shadows the story, which ends with one of the great controversies of Victorian science: Robert FitzRoy’s first forecasts of the 1860s.

Peter Moore is an English historian. He lives in London and teaches non-fiction creative writing at City University. He has published two books, an acclaimed history of a double murder, Damn His Blood, and his most recent The Weather Experiment.

Peter Moore is an English historian. He lives in London and teaches non-fiction creative writing at City University. He has published two books, an acclaimed history of a double murder, Damn His Blood, and his most recent The Weather Experiment.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of The Weather Experiment in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”

Laura J. Snyder, “Eye of the Beholder”

Stephanie Dalley, “The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon”

June 11, 2015

Muffin Man

By Beth Dunn (Guest Contributor)

Were George Handel and a buttered muffin inadvertently responsible for the creation of the British Museum?

Were George Handel and a buttered muffin inadvertently responsible for the creation of the British Museum?

Well, probably not.

But honestly? I wouldn’t rule it out, either.

So you know the British Museum. First public secular museum, established in 1753 when Sir Hans Sloane passed away and left his absurdly large and varied collection of rare books, antiquities, and just downright oddities to the British Crown.

Sloane was a wildly successful London doctor, one who counted Samuel Pepys and Queen Anne among his patients, and who had amassed a cabinet of curiosities so large that he had to buy the house next door just to give him enough shelf space for it all.

Distinguished visitors would come from all over to peer at his whatnots, to marvel at his whoosits.

Then he passed away and left it all to the nation, who responded with characteristic ingratitude, a great deal of Parliamentary wrangling, and no small amount political corruption that eventually resulted in the creation of the British Museum.

What’s odd about this story is that it is hardly possible to research the early days of the British Museum without coming across the following story with what one can’t help but notice is alarming frequency:

Sloane’s house was visited by numerous people. Among them was the composer Handel, who is said to have outraged his host by placing a buttered muffin on one of his rare books.

For the life of me, I cannot stop thinking about that damn buttered muffin.

What kind of muffin was it? Was it more extravagantly buttered than most? Exactly what sort of baked good was called a muffin back in the 18th century, anyway?

Was Handel some sort of countrified rube, who simply thought that rare books made excellent substitutes for plates and saucers, or was he trying to make some kind of point? What book was it?

Was it this near catastrophe that convinced Sloane that his collection needed the protection of the British Crown, once he himself was no longer around to protect his books from the menace of butter-laden muffins, crumpets, and scones?

Even more intriguingly, is there in some dim and dusty corner of the British Library (where all the books of the British Museum eventually found a home) an old, rare book with one very faded, but barely discernable circular grease stain on it?

These are the sorts of questions that leads one to investigate, late at night and into the early morning hours, the history of the English Muffin, and to discover (to one’s great delight) that the muffin was in fact a highly fashionable foodstuff in the 18th century.

Which would explain why it was being served to distinguished visitors to what one has to assume was one of the more exclusive drawing rooms in London at the time.

Muffins were huge. They were a tremendous fad, catching on among the snacking classes with such fervor that scores of muffin factories soon popped up all over London. Jane Austen even mentioned muffins in her novel Persuasion, and not merely as a particularly apt way of describing the hot, buttery Captain Wentworth.

Did Sloane realize the peril his collection might be in, if left open to the slings and arrows of outrageous baked goods?

Or was Handel just a bit of a jerk?

Hard to say.

But in the midst of this deeply appealing line of research, I suddenly remembered another buttered muffin story, this time about one of the American founding families. I got very excited for a few minutes, imagining that the tale of the buttered muffin was some sort of universal flood story, found in one form or another in all known cultures, varying only in the shape and size of the muffin, or in the amount of butter involved.

Alas, it was a more prosaic tale that that. Something about a young lad who was named after Benjamin Franklin, and who took it upon himself to instruct First Lady Dolley Madison in the art of properly buttering your muffin. If you’ll excuse the expression.

‘Why, you must tear him open, and put butter inside and stick holes in his back! And then pat him and squeeze him and the juice will run out!’

Which seems a very sensible way to eat a buttered muffin, if you ask me.

What’s truly excellent about this story is that it is a reminiscence of Thomas Jefferson’s great-granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Harrison. And that the story took place at Monticello.

Buttered muffins. Present at the creation of so many great things.

Perhaps now you, like me, wish to know just how Thomas Jefferson ate his muffins.

Very well, I shall tell you.

To a quart of flour put two table spoonsfull of yeast. Mix . . . the flour up with water so thin that the dough will stick to the table. Our cook takes it up and throws it down until it will no longer stick [to the table?] she puts it to rise until morning. In the morning she works the dough over . . . the first thing and makes it into little cakes like biscuit and sets them aside until it is time to back them. You know muffins are backed in a gridle [before?] in the [fire?] hearth of the stove not inside. They bake very quickly. The second plate full is put on the fire when breakfast is sent in and they are ready by the time the first are eaten.

Who’s hungry?

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, and gets pretty worked up sometimes about baked goods.

Image by foonus

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in January 2012.

June 10, 2015

They’re Alive!

By Laura J. Snyder (Guest Contributor)

Are they really alive? Antoni Leeuwenhoek was stupefied.

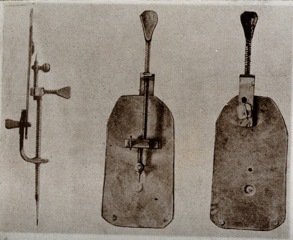

It was a bright day in the summer of 1674, and Leeuwenhoek was sitting in his study in the small Dutch town of Delft. A cloth salesman turned microscope maker, Leeuwenhoek had closed up the shutters, leaving only a small hole through which a beam of light entered the room. He picked up one of his devices: a brass oblong about two and a half inches long and one inch wide, with a tiny bead of glass in its center. Attached to the back of the device was a glass tube the width of a human hair. Leeuwenhoek filled the tube with a drop of water taken from the Berkelse Mere, a lake two hours by foot from Delft.

Leeuwenhoek Microscope, Wellcome Library, London

Lifting the microscope to his eye Leeuwenhoek peered upwards into the light, as if looking at the stars through a telescope. He gazed at the water in the tube, focusing the device by turning this way and that a tiny screw attached to it. Perhaps he was expecting to see tiny “globules” in the water, like those he had recently observed in his own blood. Minuscule shadows began to come into view. Leeuwenhoek continued to focus the device. Then, suddenly, something appeared that was so incredible his hands began to shake, nearly spilling the water in the tube.

He rested the microscope on the desk for a moment, took a deep breath, and began again. His eyes were not deceiving him. They saw not tiny globules, but particles of different shapes—round, oval, snake-like—some larger and other smaller. Most fantastically, these shapes were moving themselves by means of minuscule fins and legs and wings. They were living creatures! As Leeuwenhoek later related to the Royal Society of London, “the motion of these little animals in the water was so swift, and so various, downwards, and round about, that I confess I could not but wonder at it.”

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, By Johannes Verkolje, ca. 1686, Wellcome Library

Leeuwenhoek had just discovered microscopic life. For the first time, someone realized that there was a world of tiny creatures invisible to naked vision—that in the universe there was more than meets the eye. This discovery would transform biology, anatomy, medicine, even, eventually, Delft’s brewing industry, in the period we call the “scientific revolution.”

Leeuwenhoek was not the only genius working with lenses in Delft. At the same time, across the Market Square, a man born the same week as Leeuwenhoek was also using lenses and optical devices to see what no one else had seen before. The artist Johannes Vermeer was making his own optical experiments to understand how light works to help us see, and to paint the most luminous works ever beheld.

Eye of the Beholder tells the story of the intersecting lives of Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, and the remarkable transformation they wrought in how we see the world—a transformation that lives with us today.

Laura J. Snyder is a Fulbright scholar and the author of Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. Her previous book, The Philosophical Breakfast Club, was a Scientific American Notable Book, winner of the 2011 Royal Institution of Australia poll for Favorite Science Book, and an official selection of the TED Book Club. To learn more about Laura and her books see laurajsnyder.com.

Laura J. Snyder is a Fulbright scholar and the author of Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. Her previous book, The Philosophical Breakfast Club, was a Scientific American Notable Book, winner of the 2011 Royal Institution of Australia poll for Favorite Science Book, and an official selection of the TED Book Club. To learn more about Laura and her books see laurajsnyder.com.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Eye of the Beholder in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”

Laura J. Snyder, “Eye of the Beholder”

Stephanie Dalley, “The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon”

June 9, 2015

A Very Dangerous Woman: Baroness Moura Budberg

By Jeremy Dronfield (Guest Contributor)

Spy, seductress, aristocrat, Baroness Moura Budberg was a mystery to everyone who knew her, even her closest friends and her children.

In London in the 1950s, she was a renowned saloniste; nobody else had the magnetic charm or the air of danger and mystery that surrounded Baroness Budberg, and her soirées attracted Graham Greene, Laurence Olivier, Guy Burgess, Bertrand Russell, David Lean, E. M. Forster, Peter Ustinov – all came to drink gin and vodka and be enchanted.

saloniste; nobody else had the magnetic charm or the air of danger and mystery that surrounded Baroness Budberg, and her soirées attracted Graham Greene, Laurence Olivier, Guy Burgess, Bertrand Russell, David Lean, E. M. Forster, Peter Ustinov – all came to drink gin and vodka and be enchanted.

In her prime she had been the mistress of both Maxim Gorky and H. G. Wells, both obsessed with her. Wells, whose proposals of marriage she turned down repeatedly, thought her the most compellingly attractive woman alive, and he wasn’t the only one.

There were always rumours about her: a spy, a double agent in the service of British and Russian intelligence… She knew everybody who was anybody, and knew everything about them. People entering her circle were warned to watch their step and their tongues – Moura knew all, saw all, and had powerful, dangerous connections. But hardly anyone could resist her company.

She was a figure made partly out of fables and lies – some of her own invention. She had spied for the Germans in the First World War; had spied for and against the British and the Russians and the Ukrainians; had worked as an agent for the terrifying Bolshevik secret police during the Red Terror of the Revolution; was the mistress of a British agent who plotted to bring down Lenin; had been the trusted agent of Stalin; and might even have committed murder.

Moura’s greatest adventure was her first – her intense love affair with the British diplomat and secret agent Robert Bruce Lockhart in revolutionary Russia, and her entanglement in his plot to bring down the Bolshevik government, which led to her sacrificing herself to save his life.

In her later life, publishers tried to persuade her to produce an autobiography, but although she took and spent the advance money, not a word was written, and most of her papers were burned shortly before she died in 1974. Several biographies were attempted, but most came to nothing for lack of source material, or were tissues of invention. Since then, more material has come to light: the archives of letters to Gorky, Wells, and Lockhart, and the file kept on her by MI5 from 1920 to 1951. With new research into the “Lockhart Plot” to bring down Lenin, it’s now possible to piece together the full story of Moura’s incredible life, and uncover some startling facts.

It’s tempting to be cynical about Moura’s lies, which were really no more dramatic than the truth. Whatever she did, she was intent on creating an “artistic truth” for herself. During her intimacy with Maxim Gorky, when she delved into the mind of a literary creator, she tried to sum up how Gorky converted life experience into narrative drama – “Artistic truth is more convincing than the empiric brand, the truth of a dry fact.”

Where Gorky created literary art out of people’s lives, Moura tried to create – in the act of living – an artistically “true” life for herself. Whether it was a romantic farewell in a night-time train station, a vow to love unto death, a noble valediction on a mountain crag, or sacrificing herself to the murderous secret police, Moura invariably played her part to the full.

Moura Budberg, Preface to Gorky, Fragments, p. ix.

Jeremy Dronfield is a biographer and novelist. His books include the novels The Locust Farm and The Alchemist’s Apprentice, and most recently, Beyond the Call, the true story of a US pilot’s secret rescue mission on the Eastern Front in World War II, written for the son of the book’s hero. He lives in Cambridgeshire, England. His coauthor of A Very Dangerous Woman, Deborah McDonald is also the author of Clara Collet 1860-1948: An Educated Working Woman and The Prince, His Tutor and the Ripper: The Evidence Linking James Kenneth Stephen to the Whitechapel Murders. She lives on the Isle of Wight, England.

Jeremy Dronfield is a biographer and novelist. His books include the novels The Locust Farm and The Alchemist’s Apprentice, and most recently, Beyond the Call, the true story of a US pilot’s secret rescue mission on the Eastern Front in World War II, written for the son of the book’s hero. He lives in Cambridgeshire, England. His coauthor of A Very Dangerous Woman, Deborah McDonald is also the author of Clara Collet 1860-1948: An Educated Working Woman and The Prince, His Tutor and the Ripper: The Evidence Linking James Kenneth Stephen to the Whitechapel Murders. She lives on the Isle of Wight, England.

W&M is excited to have two (2) copies of A Very Dangerous Woman in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”

June 8, 2015

Vesalius – The Ultimate Wedding Present?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

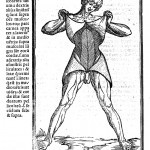

L0021650 A. Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

It’s still ‘Vesalius year’. The great anatomist was born in 1514, but so many places want to honor him on his 500th anniversary that conferences and exhibitions are still going on to the end of 2015. I’m just back from one in Padua and have also been to one in Leuven – it’s useful that he is linked to so many interesting cities in Europe!

But the enthusiasm for holding a Vesalius party is not restricted to those places where he trained or worked. When I was in Padua, we were told about the exciting plans for an exhibition later this year being put on by the Rare Books people at Duke University, who already have an excellent record for making medical history accessible with their exhibition on ‘Animated Anatomies’. In the USA alone, there are still over 60 copies of the first edition of Vesalius’ great work, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), the vast majority of these in libraries rather than private collections. The stories about these copies are themselves amazing.

Here, for example, from Joffe and Buchanan’s recent census of the copies in the USA, is Dr W.G. MacCallum writing to the librarian at the New York Academy of Medicine in July 1939:

“In 1903 I was walking toward a bridge over the river in Rome & saw a blacksmith shop with the blacksmith in a shower of sparks hammering on the anvil – through the shower I saw a bench covered with old books. I went in and found the first edition of Vesalius’ Fabrica 1543 and bought it. On my return I gave my copy to Harvey Cushing as he was so greatly interested in Vesalius. Sometime afterward Dr. O. [William Osler], who had three, I believe, gave one to Barker as a wedding present, one to Cushing and took mine and sent it to McGill. From there it was sent to your library”.

Both Padua and Leuven are going beyond books in their representations of Vesalius. In the Leuven Museum M the description of ‘Vesalius. Imagining the Body’ warns: “Be amazed by the ‘living’ dead who candidly reveal what is concealed under their skin”. This is a reference to an extraordinary piece in which a video projection from four projectors is made on to a life-size model of a naked man. It is very disturbing because the projection gives the impression that this is a man who is alive, moving and breathing – until he raises his right hand and starts to draw a line on his chest which then extends to other parts of his body which apparently open up so that he ‘dissects himself’,until his flesh falls off to reveal his bones. In Museum M, this was shown in a reconstructed sixteenth-century anatomy theater. A few years before it was shown in an actual (although more recent) anatomy theater in the city. There’s a film of this – Vesalius Revisited – available. Those of a nervous disposition may be reassured by the fact that at the end of the ‘dissection’, the process is reversed.

The video artist here is the Leuven-based Filip Sterckx. His self-flaying man is a clear reference to early modern images, whether these are the highly accomplished full-body figures in Vesalius or the cruder, rather cheerful figures who helpfully open up their abdomens for us.

The video artist here is the Leuven-based Filip Sterckx. His self-flaying man is a clear reference to early modern images, whether these are the highly accomplished full-body figures in Vesalius or the cruder, rather cheerful figures who helpfully open up their abdomens for us.

L0013262 Muscles – Berengarius 1521, Credit: Wellcome Library

In Padua, at MuSME, they have a far more than life-size version of Sterckx’s installation. When we were there, before the official opening of this new museum, the projections on to the body were not of a dissection in progress, but of a range of historical images of the body, including some taken from Vesalius.

But the best news of all is that you don’t need to travel to see the work of Vesalius. The Turning the Pages project at the National Library of Medicine provides a selection of illustrated pages from this amazing book. Celebrate the anniversary by having a look!

June 6, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: The Historical Listicle

By April Stevens (W&M Managing Editor)

Are you familiar with the listicle? No, that isn’t a word I just created. According to the Oxford English Dictionary a listicle is “an article on the Internet presented in the form of a numbered or bullet-pointed list”. Even if you weren’t familiar with this term, you are probably quite familiar with the listicle itself. This week we are sharing some of the recent and engaging historical listicles.

That’s Simply Medieval!

It seems every other day you hear about a new poll that talks about the mounting stress and anxiety westerners face over any number of issues: work, money, family. Far from a new dilemma, worrying spans the ages. History Extra presents the Top 9 things that Medieval Londoners worried about. Not surprisingly, health, money and relationships make the list, but some items may surprise you.

Add to that list of Medieval concerns: serial killers? They may not have been called serial killers at the time, but murder and psychopaths have existed since the dawn of time. Listverse (a website devoted to listicles!) gives us the fearsome 10 Forgotten Serial Killers from the Middle Ages, including Peter Stumpp, a cannibal killer called the “Werewolf of Bedburg”. Some figures on this list may admittedly be more fantasy than fact, like Christman Genipperteinga who allegedly murdered 984 people between 1568-1581, and likely represent multiple killers who became legend.

Wh at is the solution to Medieval serial killers? Why, Medieval Superheroes of course! Marvel Comics isn’t the only one spreading tales of magical rescues and superhuman abilities, in fact, some modern superheroes may be borrowing from their Medieval counterparts! In Medievalist.Net’s Top Ten Superheroes of the Middle Ages, we are introduced to “superheroes” like Golem of Prague, an invisible stone creature that could be animated with prayers. Or consider, Seigfried, the hero of a German epic whose body is invincible and is armed with his cloak of invisibility. Sound familiar?

at is the solution to Medieval serial killers? Why, Medieval Superheroes of course! Marvel Comics isn’t the only one spreading tales of magical rescues and superhuman abilities, in fact, some modern superheroes may be borrowing from their Medieval counterparts! In Medievalist.Net’s Top Ten Superheroes of the Middle Ages, we are introduced to “superheroes” like Golem of Prague, an invisible stone creature that could be animated with prayers. Or consider, Seigfried, the hero of a German epic whose body is invincible and is armed with his cloak of invisibility. Sound familiar?

That’s Just Plain Crazy!

Napoleon Bonaparte: emperor, egomaniac, romance novelist? Yes, Napoleon was also something of a writer, of short stories at least. Considered a bit of an eccentric historical figure by many, the listicle 10 Wild Stories about Napoleon shares even more strange tales. Did Napoleon shoot off the sphinx’s nose? Did he poison his wounded? Read the listicle to find out!

Napoleon waged some successful wars but also suffered some bitter defeats. Imagine if alcohol was to blame for these losses? The emperor’s army didn’t suffer this fate, but according to the list 7 Times Alcohol Decided the Course of Battle other armies did fall to the temptation of fire water. Read amusing tales about the samurai that partied so hard they didn’t realize they were being attacked or the Ottoman sultan who lost his entire navy for some casks of wine in the listicle.

Want to read more surprising history? Check out these recent posts on Wonders & Marvels:

How Does Your Book Collection Compare with the Hoard of Bibliomaniac Richard Heber?

Dying of Homesickness, from San Francisco to Versailles

Need even more reading material? Make sure to register for our Monthly Book Giveaways!

June 4, 2015

King of the Lobby

By Kathryn Allamong Jacob (Guest Contributor)

The ring–a five-carat sapphire surrounded by 42 glittering diamonds–flashed each time Sam Ward gestured to emphasize a point, and he had many points to make. The ring’s fire distracted members of the House Ways and Means Committee trying to concentrate on this lively witness’ testimony in January 1875. The congressmen didn’t want to miss a word of what Ward had to say. Already within the first few minutes, he had made them laugh so hard that the stenographer was obliged to insert “[laughter]” into the official transcript.

The ring–a five-carat sapphire surrounded by 42 glittering diamonds–flashed each time Sam Ward gestured to emphasize a point, and he had many points to make. The ring’s fire distracted members of the House Ways and Means Committee trying to concentrate on this lively witness’ testimony in January 1875. The congressmen didn’t want to miss a word of what Ward had to say. Already within the first few minutes, he had made them laugh so hard that the stenographer was obliged to insert “[laughter]” into the official transcript.

This hearing was supposed to be a serious affair. The committee was investigating the latest scandal to rock the second Grant administration. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company had allegedly pried out of Congress a subsidy to carry the mail to the Orient only after greasing the skids (and several palms) with what one newspaper claimed was the extraordinary sum of one million dollars. Sam Ward’s name turned up on a list of men who profited by the deal.

The witnesses who preceded him sweated through their testimony. Not Sam Ward. Five-feet eight-inches tall, with a perfectly cut suit, shiny bald head, and precisely trimmed Van Dyke beard, one reporter claimed he “fairly gleamed with good living” as he strode into the chamber with a self-assured air. His regal bearing was no surprise. Sam Ward was known to everyone in the room and far beyond Capitol Hill as “The King of the Lobby.”

Combining delicious food, fine wines, and excellent conversation, he had perfected a new type of lobbying–social lobbying. While most Washington banquets were big, dreary affairs, guests called his intimate dinners “the climax of civilization.” His art was to guarantee that the congressmen he entertained never focused on the purpose that lurked beneath his perfectly cooked poisson.

Kathryn Allamong Jacob, author of King of the Lobby, is curator of manuscripts at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

IMAGE:After lecturing a House committee on the hazards of lobbying and the importance of dining well, Sam Ward told a parable about a cook, the king of Spain, and a meal of pigs’ ears. In this newspaper cartoon, he cooks up a pot of $1,000 pigs’ ears himself. (New York Daily Graphic, December 20, 1876.)

This post first appeared on Wonders & Marvels in January 2010.

June 2, 2015

Good Time Girls

By Carol Dyhouse (Guest Contributor)

Who or what was ‘a good time girl’? A closer look at the way this term was used during the 1950s can tell us a lot about women’s history.

In the 1950s, the popular image of a good time girl centred on the female body: prominent and often very pointy breasts, a wasp-like waist and generous hips. A good time girl was a ‘glamour puss’, with rouged lips and peroxide-blonde hair. She posed with an inviting, come-and-get-me-look, a representation which played around the boundaries of soft porn.

In the 1950s, the popular image of a good time girl centred on the female body: prominent and often very pointy breasts, a wasp-like waist and generous hips. A good time girl was a ‘glamour puss’, with rouged lips and peroxide-blonde hair. She posed with an inviting, come-and-get-me-look, a representation which played around the boundaries of soft porn.

In Britain this image was embodied by film-star Diana Dors, a woman who relished scandal and celebrity, and who both exploited and was exploited by the male-dominated media of her day. As a sixteen year girl, Diana Dors had played the part of a troubled teenager in the British film, Good Time Girl (1948). The film was presented as a cautionary tale, warning young girls against a life of pleasure. Even so, it caused immense controversy, and there were sustained – though unsuccessful – attempts to get it banned.

Descriptions of the good time girl appeared in unlikely places. In 1946, the British Medical Journal drew attention to the figure, and to the social problems laid at her door. Many adolescent girls showed precocious physical development, the writer argued, especially in the breast and hips. They were cunning, and targeted good-looking men with money. ‘They spend a great deal of time on making up their faces and adorning themselves’, the article continued, ‘though they often do not trouble to wash and are sluttish about their undergarments’.

Descriptions of the good time girl appeared in unlikely places. In 1946, the British Medical Journal drew attention to the figure, and to the social problems laid at her door. Many adolescent girls showed precocious physical development, the writer argued, especially in the breast and hips. They were cunning, and targeted good-looking men with money. ‘They spend a great deal of time on making up their faces and adorning themselves’, the article continued, ‘though they often do not trouble to wash and are sluttish about their undergarments’.

Good time girls were seen as a social problem, wayward and out of control. But only the thinnest of dividing lines separated the folk-devil from the sex object, pouting her lips for male delectation. If the men were confused, where did this leave the women? No wonder some of them brazened it out.

Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women (Zed Books, 2014) tells the story of the challenges and opportunities faced by young women growing up in the twentieth century, and the pop-hysteria and moral panic that has so often accompanied their progress.

Carol Dyhouse has spent most of her career in academia, researching, writing and teaching about the history of women in modern Britain. She is currently a professor (emeritus) of history at the University of Sussex. Carol has written extensively on the subjects of girls’ schooling and women in higher education. Her most recent books are Glamour: Women, History, Feminism, (Zed Books, London, 2010), and Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women (Zed Books, 2014).

Carol Dyhouse has spent most of her career in academia, researching, writing and teaching about the history of women in modern Britain. She is currently a professor (emeritus) of history at the University of Sussex. Carol has written extensively on the subjects of girls’ schooling and women in higher education. Her most recent books are Glamour: Women, History, Feminism, (Zed Books, London, 2010), and Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress in the History of Young Women (Zed Books, 2014).

W&M is excited to have two (2) copies of Girl Trouble in this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on June 29th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

June Book Giveaways

Carol Dyhouse, “Girl Trouble”

Dronfield and McDonald, “A Very Dangerous Woman”

Nancy Goldstone, “The Rival Queens”

Peter Moore, “The Weather Experiment”