Holly Tucker's Blog, page 27

July 23, 2015

Al Capone Never Shut-Up

By Jonathan Eig (Guest Contributor)

For a criminal, this was probably not such a good thing. But for me, as a Capone biographer, it was wonderful. It seemed that every time a reporter phoned or knocked at his door, Capone pulled up a chair and settled in for a chat. Sometimes he talked about his family, sometimes about his career; most of the time he seemed to be pleading for understanding. This took me by surprise.

For a criminal, this was probably not such a good thing. But for me, as a Capone biographer, it was wonderful. It seemed that every time a reporter phoned or knocked at his door, Capone pulled up a chair and settled in for a chat. Sometimes he talked about his family, sometimes about his career; most of the time he seemed to be pleading for understanding. This took me by surprise.

Here’s a snippet from one of my favorite interviews:

“What does a man think about when he’s killing another man in a gang war? Well, maybe he thinks that the law of self-defense, the way God looks at it, is a little broader than the law books have it. Maybe it means killing a man who’d kill you if he saw you first. Maybe it means killing a man in defense of your business, the way you make your money to take care of your wife and child. I think it does. You can’t blame me for thinking there’s worse fellows in the world than me.”

Other gangsters were horrified by Capone’s gabfests. They worked hard to keep their names and faces out of the newspapers. Why not Capone? I suspect several factors were at work.

First, he was a genuinely gregarious fellow (when he wasn’t in a murderous rage, anyway). Second, these were the 1920s, when men and women craved celebrity and considered it good for a person’s business prospects. And third, Capone convinced himself that he was, at least to an extent, a man providing the people with goods and services they desired.

He came of power during Prohibition, a wildly unpopular law, and he got rich by breaking that law. Almost everyone broke it, of course. Capone broke it in a much bigger way.

Still, you really can’t blame him for thinking there were worse fellows in the world than him.

Jonathan Eig is author of Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster

Jonathan Eig is author of Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster , and a former writer and editor for the Chicago bureau of The Wall Street Journal and the former executive editor of Chicago magazine. He is the author of two highly acclaimed New York Times best sellers: Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig and Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. Luckiest Man won the Casey Award for best baseball book of 2005 and Opening Day was selected as one of the best books of 2007 by the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Sports Illustrated.

, and a former writer and editor for the Chicago bureau of The Wall Street Journal and the former executive editor of Chicago magazine. He is the author of two highly acclaimed New York Times best sellers: Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig and Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. Luckiest Man won the Casey Award for best baseball book of 2005 and Opening Day was selected as one of the best books of 2007 by the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and Sports Illustrated.

July 21, 2015

The Business of America’s Native Spirit

By Reid Mitenbuler (Guest Contributor)

In 1964, Congress passed a resolution declaring bourbon whiskey “a distinctive product of the United States.” The legislation was rather boring, a simple act of trade protectionism that prevented foreigners from making a similar product and calling it by the same name. It basically meant that U.S. producers of this whiskey style, which was invented here, would have fewer competitors.

Nevertheless, the  marketing departments of booze companies decided to use the legislation to their advantage. They reimagined it as a loving tribute bestowed by lawmakers upon a humble drink embodying great American virtues, the same qualities found enshrined in the frontier iconography on so many bourbon labels. The dry language “a distinctive product of the United States” was upgraded to “America’s Native Spirit”—a misquote, but a spiffy one—and bourbon eventually ended up in the canon of American greats, alongside baseball and apple pie. It was mythmaking at its best: transforming a dull kernel of truth into something magical.

marketing departments of booze companies decided to use the legislation to their advantage. They reimagined it as a loving tribute bestowed by lawmakers upon a humble drink embodying great American virtues, the same qualities found enshrined in the frontier iconography on so many bourbon labels. The dry language “a distinctive product of the United States” was upgraded to “America’s Native Spirit”—a misquote, but a spiffy one—and bourbon eventually ended up in the canon of American greats, alongside baseball and apple pie. It was mythmaking at its best: transforming a dull kernel of truth into something magical.

But what is really meant by “America’s Native Spirit?” How does this embody the nation? I constantly asked these questions while writing Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey. The history of America’s whiskey industry is America’s larger history on a condensed scale: the frontier colony of an empire that eventually evolved into its own global empire. During the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, the spirit represented the dueling ideologies of Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson to define the soul of American business. During the Gilded Age, it was one of the most corrupt industries in the nation, mirroring the excesses of its time.

In the twentieth century, the industry was pursued relentlessly by a Justice Department suspicious of monopolization, making the whiskey trade a perfect microcosm of the many American industries funneling their power into the hands of a few. It’s a good thing it had hired Madison Avenue to put the picture in soft focus.

“America’s Native Spirit” boils down to capitalism: a word beautiful to some and dirty to others. The tale isn’t black or white, but gray. It is both enchanting and exasperating.

The evolution of bourbon’s recipe is a tale of innovation and ingenuity: frontiersmen converting leftover grains into a valuable product they could trade; learning to age it in wooden barrels made it more valuable and tasty. But the people behind it were both craftsmen and criminals: some were focused on refining an art form while others made swill adulterated with poisons and marketed with lies. In any case, the crimes helped spur landmark reform regulations, such as the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

The evolution of bourbon’s recipe is a tale of innovation and ingenuity: frontiersmen converting leftover grains into a valuable product they could trade; learning to age it in wooden barrels made it more valuable and tasty. But the people behind it were both craftsmen and criminals: some were focused on refining an art form while others made swill adulterated with poisons and marketed with lies. In any case, the crimes helped spur landmark reform regulations, such as the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

The history of American whiskey is one of those great stories with an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other. Even the 1964 resolution was product of a man with a mixed record: Lewis Rosenstiel, a corporate titan who at one point owned a majority of all the aged whiskey in the country. He got his start in organized crime during Prohibition—indicted, although never convicted—but later went legitimate and donated over $100 million to charity, stopping along the way to lobby Congress for legislation that would help him become one of the richest men in the country.

But that was before Rosenstiel lost his business in a hostile corporate takeover. Nevertheless, stories like Rosenstiel’s illuminate the term “America’s Native Spirit” and give life to all the mythic labels on the bottles: a multibillion-dollar industry built around a commodity able to both enchant and intoxicate. The story of a nation, for better and for worse.

Reid Mitenbuler is the author of Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Slate, Salon, and Whisky Advocate, among other publications. He lives in Brooklyn

Reid Mitenbuler is the author of Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Slate, Salon, and Whisky Advocate, among other publications. He lives in Brooklyn

July 20, 2015

The Duchess Mazarin, Runaway Woman and Travelling Corpse

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith, Regular Contributor

When Cardinal Mazarin, prime minister of France died in 1660, on his deathbed he settled a marriage contract for his 15-year-old niece Hortense Mancini. Her betrothed was a religious fanatic over twice her age, whose only passion other than prayer and zealotry was a jealous possessiveness of his beautiful young wife. The Cardinal bequeathed a fortune and also his name to the couple, leaving Hortense, in her own words, “the richest heiress and the unhappiest woman in Christendom.”

When Cardinal Mazarin, prime minister of France died in 1660, on his deathbed he settled a marriage contract for his 15-year-old niece Hortense Mancini. Her betrothed was a religious fanatic over twice her age, whose only passion other than prayer and zealotry was a jealous possessiveness of his beautiful young wife. The Cardinal bequeathed a fortune and also his name to the couple, leaving Hortense, in her own words, “the richest heiress and the unhappiest woman in Christendom.”

During the 7 years that she remained with her husband, the young Duchess Mazarin produced 4 children and submitted to Armand’s jealous rages, as he dragged her along with him on trips to his distant properties and then locked her up at home when they returned to Paris. Then she decided to try to obtain a legal separation. Failing in that attempt, she ran away, leaving her children behind. From the day she hit the road in June 1667, she was a celebrity. Her escapades and travels were followed with great interest by readers of the news gazettes that were then popping up all over Europe. It was assumed that she had taken a lover, for why else would a woman leave such wealth behind? (Leaving the children didn’t inspire much commentary.) The exiled courtier Bussy-Rabutin, famous for his running observations on court intrigue, wrote that “no cuckold has ever been so deserving of the title as the Duke Mazarin, and every day of his life gives me more admiration for his wife, who prefers to take to the road rather than suffer his presence any longer.”

Ortensia Mancini, as Aphrodite

On the road she encountered bandits, avoided pursuers, crossed paths for awhile with other runaway women, and learned to exploit the anonymity of a system of public conveyance via postal coach, newly introduced in France. She took refuge with sympathetic noblemen such as the powerful Duke Charles-Emmanuel of Savoy, who was enchanted with her and cared little for threats coming from France and Italy demanding that she be returned to her husband. When she was forced to leave Savoy after Charles-Emmanuel’s death in 1675, she traveled – in winter! – through Switzerland, Germany, and Holland. She narrowly escaped shipwreck in the English channel and made her way to London, where her second cousin, Mary of Modena, was wife to the king’s brother. She immediately attracted the notice of King Charles I and became his mistress.

Meanwhile her morose French husband had lost none of his jealous desire to make her come back to him. In 1689, over twenty years after his wife had left him, the Duke Mazarin brought suit against Hortense to force her to give up her libertine lifestyle and return to France to resume conjugal life. He may have thought the time propitious – Hortense had lost the pensions that had been awarded to her by King Charles II, who had died in 1685. The decision of the law court came down in favor of the Duke, but Hortense stayed in London and refused to change her habits or reject her epicurean friends. She remained in England for another nine years, heavily indebted, until her death in 1699.

As a runaway wife in exile, Hortense had always been in the news, and in death her very moveable body continued to receive attention. Some of her creditors, hoping to recover their losses from her family in France, successfully laid claim to her corpse and demanded payment. And after all those years of refusing to send her money and trying to force his indigent wife’s return, the Duke Mazarin decided to pay up. He negotiated a settlement, delivering the sum in person to London.

But while it was expected that he would bring his wife home to a family sepulcre, crazy Armand had other ideas. He paraded her body around France, from Alsace to Brittany, to precisely those properties that she had so detested visiting in the early years of their marriage. Was he carrying out his revenge on Hortense’s celebrated ability to travel where and when she pleased? Slowly and ceremoniously he transported the casket to each of his provincial estates before finally, four months later, allowing himself to be persuaded to bury her.

For further reading:

The Memoirs of Hortense and Marie Mancini, edited and translated by Sarah Nelson (2007).

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her Sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin (2012).

July 19, 2015

How I Write History…with Dronfield and McDonald

An Interview with Jeremy Dronfield and Deborah McDonald (Guest Contributors)

Wonders & Marvels: Both of you have written books on your own as the sole author, but most recently you have collaborated on A Very Dangerous Woman: The Lives, Loves, and Lies of Russia’s Most Seductive Spy. How does working with a co-author change your writing process? How did you divide the work?

Deborah McDonald: In our case I initiated the work, did the research, organized the material, wrote the book and then sent it off to my agent. He liked it and began sending it to potential publishers but a couple of them rejected it as they felt it was too dry and ‘academic’. So my agent introduced me to Jeremy who took on the task of making it a more exciting read in the course of which he became intrigued with Moura’s life himself and did his own exploration of the subject and added to the book. It thus became a truly collaborative work.

Deborah McDonald: In our case I initiated the work, did the research, organized the material, wrote the book and then sent it off to my agent. He liked it and began sending it to potential publishers but a couple of them rejected it as they felt it was too dry and ‘academic’. So my agent introduced me to Jeremy who took on the task of making it a more exciting read in the course of which he became intrigued with Moura’s life himself and did his own exploration of the subject and added to the book. It thus became a truly collaborative work.

Jeremy Dronfield: I first approached the project as a consultant, to give Deborah some input on how best to bring Moura’s story to life. But as soon as I looked at the manuscript, I knew that there was a really special story here. Viewing it as a novelist, I saw a narrative with a natural plot which would rival most dramatic romances; viewing it as an academic (I’m a trained researcher with a PhD in archaeology), I saw the light that Moura’s story casts on the history of the Russian Revolution – its politics, intrigues, and the effect it had on the lives of Russian aristocrats.

Jeremy Dronfield: I first approached the project as a consultant, to give Deborah some input on how best to bring Moura’s story to life. But as soon as I looked at the manuscript, I knew that there was a really special story here. Viewing it as a novelist, I saw a narrative with a natural plot which would rival most dramatic romances; viewing it as an academic (I’m a trained researcher with a PhD in archaeology), I saw the light that Moura’s story casts on the history of the Russian Revolution – its politics, intrigues, and the effect it had on the lives of Russian aristocrats.

I quickly got much more closely involved, and it became a collaboration. Working from Deborah’s draft – in which she had painstakingly mapped out the course of Moura’s complex and elusive life – and from the source materials (mainly Moura’s fascinating letters to her secret agent lover, Lockhart), I began drafting the book as a fully realized dramatic narrative, at the same time further consolidating the historical foundations. The end result, I hope, is a book that has the storyline and pace of a novel and the factual rigor of an academic biography.

W&M: What are the benefits to working with a partner on a writing project of this magnitude? What are the challenges?

Deborah McDonald: The benefits have been that the book has been rewritten in a way that will appeal to a much wider audience. It enabled us to find a good publisher. The additional material Jeremy added has made the book more rounded and complete.

Jeremy Dronfield: For me, the greatest benefit of working in this way is that the huge task of primary research is already done! I’m in the privileged position of being able to come on board with an expert who has already done most of the hard work.

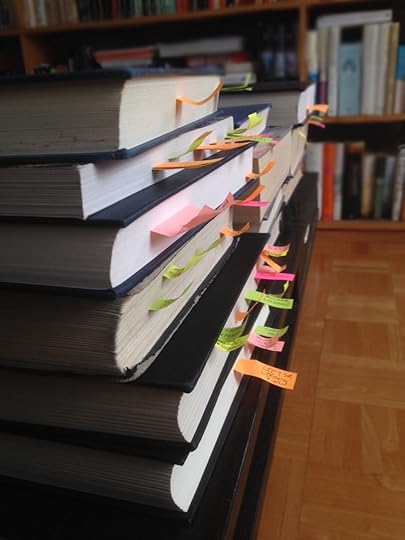

Some of the books Jeremy read to research A Very Dangerous Woman

The obvious challenge with this kind of collaboration is the risk that you won’t get on with your co-author. I’ve been fortunate in this respect, and have never had that problem. The next challenge is that I have to adapt myself to an author’s style of working with their material – how they’ve organized the source documents, their way of thinking about a subject, and so on. They also have to get used to my way of doing things! In the end it’s a compromise.

Then comes the challenge of quickly mastering the material. In the case of A Very Dangerous Woman, I had to get on top of a mountain of historical material about the Revolution, and find my way (with Deborah’s invaluable guiding hand) through the primary documents, and (again with Deborah to guide me) get to grips with the complexities of Moura’s life. Along the way, we discovered new insights into Moura’s character and the events in which she was involved. This is one of the benefits of having two pairs of eyes and two minds working on a subject – you notice things that one person alone might not.

W&M: What advice would you have for others who are considering working with a writing partner?

Deborah hard at work writing.

Deborah McDonald: Be prepared to work as a team and occasionally make compromises.

Jeremy Dronfield: Deborah is right – it has to be a team effort, and compromises may be necessary. Two writers dealing with the same subject are unlikely to always think the same way – they have different perspectives and different views of what makes a character tick. In some cases this can lead to quite long and heated debates, but happily Deborah’s and my visions of Moura’s character and motivations were pretty much in sync all the way through, so the compromises weren’t painful for either of us.

The ideal is if you can complement each other, if each of you is dominant in a complementary sphere. In writing A Very Dangerous Woman, Deborah dominated the structural, life-story side of things – the pattern and course of Moura’s life – and was the expert in the source materials, while I dominated the writing and how the story should be told. But at the same time, each of us contributed significantly to both spheres. That, I think, is the best – and perhaps the only viable – kind of balance to have if you want to achieve a successful collaboration.

If you enjoyed learning about Jeremy and Deborah’s writing collaboration, check out their recent post on Wonders & Marvels, and take a look at their wonderful book A Very Dangerous Woman: The Lives, Loves, and Lies of Russia’s Most Seductive Spy.

If you enjoyed learning about Jeremy and Deborah’s writing collaboration, check out their recent post on Wonders & Marvels, and take a look at their wonderful book A Very Dangerous Woman: The Lives, Loves, and Lies of Russia’s Most Seductive Spy.

July 18, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: Good as Gold

By April Stevens (Managing Editor, W&M)

Every society has a “golden age” in history celebrating its art, culture, and prosperity. Here at Wonders & Marvels, we think that every age is golden in one way or another. Here are a few stories from around the web that celebrate some of those golden moments in different eras.

Bronze Beauties and Golden Oldies

When you think about the Bronze Age in the future, starting thinking gold! Golden spirals that is. Over 2000 delicate golden spirals were recently unearthed in Denmark. Though the purpose of these spirals is not known, some archaeologists speculate they were part of kings or priests or attire or they may have had some sacred meaning.

When you think about the Bronze Age in the future, starting thinking gold! Golden spirals that is. Over 2000 delicate golden spirals were recently unearthed in Denmark. Though the purpose of these spirals is not known, some archaeologists speculate they were part of kings or priests or attire or they may have had some sacred meaning.

Another trove of golden treasure was discovered in a Scythian burial mound near Strovopol, Russia. More than just beautiful, these golden vessels have traces of cannabis and opium on their surfaces. These finds seem to confirm tales of drug-fueled rituals that were chronicled by the Greek historian Herodotus. Take a peek at these elaborately carved vessels and let your imagination do the rest.

Golden Concrete?

Concrete probably isn’t your first thought when the Roman Empire is mentioned, but consider the colosseum. Recent research by geophysicists reveals that the legendary concrete which has really stood the test of time may actually be inspired by volcanic chemistry. Scholars now believe that the Romans may have observed natural activity in Pozzuli that helped them to create the concrete need for the colossal scope of the colosseum.

Concrete probably isn’t your first thought when the Roman Empire is mentioned, but consider the colosseum. Recent research by geophysicists reveals that the legendary concrete which has really stood the test of time may actually be inspired by volcanic chemistry. Scholars now believe that the Romans may have observed natural activity in Pozzuli that helped them to create the concrete need for the colossal scope of the colosseum.

When you say Roman and volcanic in the same breath, most people automatically imagine Pompeii and its famously preserved frescoes. Well Pompeii, you now have some competition. A new full mural of frescoes has been discovered in Arles, France. While most Roman frescoes remaining today are fragments, the recent discovery in Arles has 11 images with vibrant colors showcasing the wealth of the region in Roman times.

When you say Roman and volcanic in the same breath, most people automatically imagine Pompeii and its famously preserved frescoes. Well Pompeii, you now have some competition. A new full mural of frescoes has been discovered in Arles, France. While most Roman frescoes remaining today are fragments, the recent discovery in Arles has 11 images with vibrant colors showcasing the wealth of the region in Roman times.

Interested in more golden moments in history? Read a few of our recent posts:

What Happened to the Hanging Garden of Babylon?

Vesalius- The Ultimate Wedding Present

July 17, 2015

Trading with the Enemy

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

Copyright Duke Riley http://www.dukeriley.info/projects/tr...

Last month was reader appreciation month at Wonders & Marvels, and today’s piece fits with that theme by connecting to an earlier, popular post about pigeon photography:

http://www.wondersandmarvels.com/2014/10/every-pigeon-tells-a-story.html

The artist Duke Riley, whose work is currently being exhibited at the 21C Hotel in Bentonville, AR, describes himself as an “artist and a patriot.” I have long been intrigued by the use of carrier pigeons for surveillance and aerial photography, and was consequently particularly taken by his project, Trading with the Enemy, for which he trained 50 pigeon collaborators and outfitted them with special handmade harnesses.

Smuggling Cigars

Copyright Duke Riley http://www.dukeriley.info/projects/tr...

The hotel’s resident curator Dayton Castleman explained that Riley was struck by the story about President John F. Kennedy ordering 1,200 Cuban cigars before signing the trade embargo in 1962. Riley was also fascinated by the role that smuggling has played in the culture of Key West, FL throughout its history and was inspired to enlist pigeons in an exploration of cigar smuggling, pop culture and political subversion, stitching individual cigar harnesses for 50 pigeons that were trained to return to a purpose-built pink loft in Key West. He also prepared 50 harnesses for filmmaker-pigeons, each embroidered with the name of a politically controversial film director.

The pigeons were released in Havana in 2013, loaded with with cigars and cameras. Not all of them made it back to Key West, but those who did carried some extraordinary footage that Riley includes in the exhibit, alongside replicas of the harnesses, the smuggled cigars encased in resin and the loft itself, currently inhabited by some local AR pigeons.

The Installation

The experience of wandering through the exhibit with Dayton Castleman as a guide was exhilarating, as the connections between the apparently disparate pieces in the installation came into focus and the story of the smuggling pigeons emerged. Aside from the playfulness of the project, Riley’s respect and affection for his winged collaborators came across strongly. As with any good story-telling installation, one has to visit to fully appreciate how the components come together.

The museum at Bentonville 21C is free and open to the public. I highly recommend the free tour at 5pm.

For more photographs and videos, and more on Duke Riley, see:

July 16, 2015

The Twice-Bought Head of Cardinal Mezzofanti

By Colin Dickey (Guest Contributor)

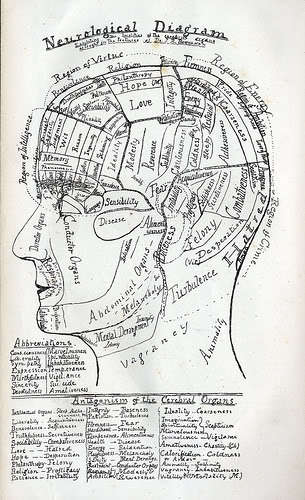

At the height of the phrenology craze, phrenologists were constantly in search of noteworthy heads that displayed specific traits or characteristics: a great military leader’s skull might be exhibited to demonstrate “combativeness,” or a renowned lover’s head might be prized for proof of the “amative” ridge. And when it came to the “language” bump, no one was more sought after than Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti.

At the height of the phrenology craze, phrenologists were constantly in search of noteworthy heads that displayed specific traits or characteristics: a great military leader’s skull might be exhibited to demonstrate “combativeness,” or a renowned lover’s head might be prized for proof of the “amative” ridge. And when it came to the “language” bump, no one was more sought after than Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti.

Mezzofanti (1774-1849) was a renowned polyglot, who read and spoke fluently thirty-eight languages and forty dialects, even though he never left his native Italy. Late in his life a phrenologist approached him, asking if he might buy the Cardinal’s skull, and exhibit it after Mezzofanti’s death as illustrative of the organs of language.

Cardinal Mezzofanti was not himself a phrenologist, and dismissed this request outright, but just after the phrenologist left, a destitute woman arrived at the Cardinal’s door, asking for assistance. Mezzofanti had no money to give, but was moved by her pleas, and called back the phrenologist, agreeing, after all, to sell him his skull, saying “On second thoughts I am inclined to treat with you for my skull, but it will be dear. I am not sure that there is such another in the world.” The price being agreed on, Mezzonfanti gave the proceeds from his skull-sale to the impoverished woman.

However, the Cardinal (according to one source) “tired of carrying on his shoulders a head belonging to another person,” and subsequently bought it back from the phrenologist, so that it could be buried with the rest of his remains in Rome.

Nevertheless, after his death rumors began to circulate that phrenologists had indeed made off with his head, and in 1885 his body was exhumed, to double-check that his skull was still attached.

It was.

Colin Dickey is a writer living in Los Angeles and the author of Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius

This post was first published on Wonders & Marvels in November 2009.

July 14, 2015

America’s First Gold Rush

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

The California Gold Rush is famous for launching an army of wealth seekers toward the West Coast and establishing an important American presence on the Pacific. Between 1848 and 1855, panners and miners unearthed tens of billions of dollars in gold (in today’s dollars) in California and swelled the population of the region by 300,000.

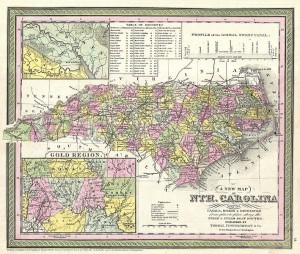

An 1850 map of North Carolina, showing the gold regions of the state.

Few know, however, that a half-century earlier and 3,000 miles away, a young boy’s fishing expedition started America’s first gold rush.

It began in 1799 in Mecklenburg (now Cabarrus) County in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, when 12-year-old Conrad Reed looked into Little Meadow Creek on his family’s property and saw an odd, shiny yellow rock. When he carried home the 17-pound chunk, his father, a Hessian veteran of the American Revolution named John Reed, thought it fit for nothing better than a doorstop. A few years later, though, the farmer took his son’s catch to a jeweler in Fayetteville, who shrewdly asked Reed how much he wanted for it. Reed naively proposed $3.50, and the bargain was made. The hunk of gold was actually worth nearly a thousand times more.

Reed soon learned he’d been hoodwinked, and he determined to find more gold on his property. He set up a mining operation on Little Meadow Creek that frequently turned up additional specimens of gold. The unearthing of a 28-pound nugget attracted gold hunters and the curious from far and wide. (President Thomas Jefferson arrived in 1804 to investigate the promise of a plentiful supply of gold.) Other successful mines sprang up in the surrounding counties, some of them venturing underground as well as along river beds, and the large local resource of gold inspired the U.S. government to open the first federal mint in nearby Charlotte in 1837.

A family legal dispute eventually idled the Reed Mine, but not before the semi-literate and relatively unskilled John Reed had become a wealthy man. North Carolina led the nation in gold production until 1848, when California took the lead. Not long after the California Gold Rush began, the Reed and its neighboring mines finally shut down. The Reed mine is now a North Carolina historic site where visitors can pan for gold, walk the abandoned mine tunnels, and explore Little Meadow Creek, whose ripples show little of the gold-seeking tumult that once roiled its waters.

Further reading:

Crayon, Porte. “The Gold Region.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, August 1857.

Hairr, John and Joey Powell. Gold Mines in North Carolina. Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

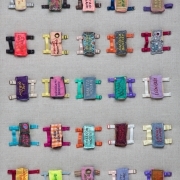

Dressing up Your Identity

By Pravina Shukla (Guest Contributor)

Every one of us gets dressed in the morning, every day of our lives. We dress to accommodate social and environmental factors, and to reflect our personal aesthetics and identities. Sending meaningful messages through dress is one way in which people engage in a daily artful endeavor, participating in what folklorists call “creativity in everyday life” or “artistic communication in small groups.”

Daily dress reflects personal identity; what we wear is affected by our body, age, gender, socio-economic class, personality, and style. Dress is who we are. Costume is often described as the clothing of who we are not. Costume is thought to be the clothing of others, of the people we are pretending to be.

Marquis de Lafayette at Colonial Williamsburg

In this book, I show that costume – like dress – is the clothing of who we are, but it signals a different self, one other than that expressed through daily dress.

Costume is set apart from dress in its rarity, cost, and elaborate materials, trims and embellishments, and in its pronounced silhouette, or exaggerated proportions. It is not meant to be ordinary, but, rather, evocative, urging the daily further along an artistic trajectory that leads to heightened communication and often culminates in a spectacle for public consumption. There is an implicit alternative persona that the costume permits its wearer to assume.

We all have multiple identities, and some of these are only expressed by means of a costume. Through particular case studies and rich ethnographic data, I will show how costume always functions to express identity.

Many of the examples of costume in this book are characterized by their wearers as transformative, as changing the wearers and the beholders somehow, taking them to mythical places, emotional depths, and off on magical journeys. In costume, people are engaged in some sort of performance, inhabiting one of the stages or dreams of their lives. They choose their clothing to fit the aim of their performance, its audience, and their own intention of meaningful communication. Like ritual, costumed events are distinct from daily existence, and therefore they allow for extreme forms of dress to aid in the formation of an alternative identity.

The book starts in Brazil where race, politics, and resistance are communicated through carnival costumes. Next it goes to Sweden where the folk costume is used as an expression of heritage. The following three chapters focus on historical awareness and education: the amateur garb of the Society for Creative Anachronism, the recreated military uniforms of Civil War reenactors, and the professional costumes of interpreters at Colonial Williamsburg. The next chapter centers on folk drama and the theatre stage.

All clothing is chosen to meet the personal and social needs of the self, and a study of costume helps refine our understanding of the function of all dress in life. In As You Like It Shakespeare’s Jacques says:

“All the world’s a stage,

“And all the men and women merely players;

“They have their exits and their entrances,

“And one man in his time plays many parts,”

The first two lines are often quoted, but the last two lines are the ones that hold particular importance for this book; throughout our lives we play many parts. Daily dress is the clothing for some of those parts, but costumes enable other parts to be played on the various stages that life slides beneath our feet.

Pravina Shukla is Associate Professor in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, at Indiana University. She is the author of The Grace of Four Moons: Dress, Adornment, and the Art of the Body in Modern India (Indiana University Press, 2008), winner of the Milia Davenport Award of the Costume Society of America and of the Coomaraswamy Book Prize of the Association for Asian Studies. She is also the co-editor of The Individual and Tradition: Folklorist Perspectives (Indiana University Press, 2011).

Pravina Shukla is Associate Professor in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, at Indiana University. She is the author of The Grace of Four Moons: Dress, Adornment, and the Art of the Body in Modern India (Indiana University Press, 2008), winner of the Milia Davenport Award of the Costume Society of America and of the Coomaraswamy Book Prize of the Association for Asian Studies. She is also the co-editor of The Individual and Tradition: Folklorist Perspectives (Indiana University Press, 2011).

July 13, 2015

What is it About the Pangolin?

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

British trains now commonly have posters encouraging travelers to text a small donation to a charity. This could be a charity supporting people, or one helping animals. Yesterday, however, I saw a poster for what was a new cause for me: a charity aiming at preventing pangolins from becoming extinct.

It’s a long time since I’ve even heard the word ‘pangolin’. The Goodies, a British TV comedy show from my distant youth, featured ‘The Terrapin Song’, which included the line “You can depend on a pangolin to get them rolling in the aisles”. But I first encountered these mammals when I was studying social anthropology at university, and they were definitely not regarded as a joke there – instead, they were a key part of Mary Douglas’ classic work Purity and Danger (1966), an important book on classification systems as a way of making sense of the world. Maybe the most famous quotation from the book is ‘Dirt is matter out of place’ – in other words, it all depends on where you think the proper place should be, as with that fine line between what counts as a weed, and what counts as a garden plant.

In this book Douglas returned to the Lele people of Zaire; she’d first written about them in 1955. Like us, they categorised animals into which they considered edible and those they did not eat. Also like us, the Lele classified some animals as part of human society – domesticated chickens for example. Anything in that category was seen as just as inedible as your family members. Just think here of the horror many of us feel at the idea of eating cats or dogs, or of the range of views in Europe on whether horses are edible or not.

The interesting thing about any classification system is what you do with things that don’t fit neatly into the categories with which you are operating. One of the most anomalous animals for the Lele is the pangolin. It’s also known as the scaly anteater, which tells you at once why it doesn’t fit: it has scales but it’s not a fish. It produces only one offspring at a time – like humans do, most of the time. So it’s sort of part-fish, part-human. As well as looking like something that should be in the water, it also climbs up trees towards the sky. And, the Lele claimed, it bows its head in the presence of its mother-in-law, as a man does! As it doesn’t fit anywhere in the classification system, it is regarded as inedible.

But specific Lele religious cults held that the in-betweenness of the pangolin makes it powerful so that eating it conveys fertility. Only a man who had produced both a son and a daughter could join the main pangolin cult. Mary Douglas, brought up a Catholic, gave an explicitly Christian analysis of some of the myths and rituals around the pangolin, for example one in which the corpse of the pangolin is carried round the village as if it were a chief. For her the pangolin was the kingly victim who, by dying, releases a power for good. Like the ram in the thicket in the story of Abraham it was also a willing victim, offering itself for sacrifice. In many other cultures, too, the ideal sacrifice is one which agrees to dying.

The importance of Douglas’ analysis is such that the image of the pangolin has been picked up across a wide range of subjects beyond anthropology. For example Iver Neumann labels Russia as ‘Europe’s main pangolin’ – it doesn’t fit, but it is still an important part of the system.

Subsequent studies of the Lele have argued that it is not so much the pangolin’s lack of fit into classification systems which is key to their role in ritual; instead, it’s due to a belief that they can tell the future, and even change it. So, for example, they feature in rain-making ceremonies. It’s clear that different groups across central Africa hold different beliefs about them and about how they should be treated. And there’s more than one kind of pangolin – in other parts of the world, too, these scaly mammals exist but are under threat.

So why is there such a threat to the pangolin today? The belief that the animal has some sort of special power has led to various types of pangolin being used in medical remedies across the world: and the focus is often precisely on those anomalous scales which can be claimed as the cure for stomach ulcers, sexually-transmitted diseases, stroke or mental illness. And it’s not just the scales. Pangolin eyes are used to treat kleptomania, apparently because the pangolin is thought to be a shy animal. The danger here is that traditional medicine is not concerned with sustainability of the plant and animal substances it uses. The demand for pangolins is such that many countries have listed them as endangered species. But people’s appetite for cures is such that the pangolin is now in serious danger of being destroyed. This strange looking mammal is at risk because of the very same features that led to it becoming a staple of undergraduate anthropology courses.

References:

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (1966)

Iver B. Neumann, ‘Europe’s post-Cold War remembrance of Russia: Cui bono?’ in Jan-Werner Mueller (ed), Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past (2002)