Holly Tucker's Blog, page 39

February 5, 2015

The Chocolate Baby

By Christine A. Jones (Former W&M Regular Contributor)

One of the strangest anecdotes to emerge from the already larger-than-life annals of Louis XIV’s reign concerns a perfectly forgettable woman, the Marquise de Coëtlogon, who lives on in infamy because she (apparently) had a chocolate addiction and the famed letter-writer Madame de Sévigné found out about it.

One of the strangest anecdotes to emerge from the already larger-than-life annals of Louis XIV’s reign concerns a perfectly forgettable woman, the Marquise de Coëtlogon, who lives on in infamy because she (apparently) had a chocolate addiction and the famed letter-writer Madame de Sévigné found out about it.

As the epistolary paparazzi of her age, Sévigné caught on paper more extraordinary plots, rumors, oddities, triumphs, and scandals than any other courtier at Versailles. To be in her midst was to risk public exposure—although she wrote her sensational tales in letters to her daughter who lived far from court in the 1670s and 80s, they also circulated regularly to others. If she was nearby when a wedding was announced or a dinner party bombed, it went out with the evening post and could be trotted out for months to come when the perfect occasion presented itself. Such was the fate of the Marquise de Coëtlogon’s darkest day.

Her story began in simple aristocratic fashion: Péronelle-Angélique de la Villeléon, hier of the noble Bois-Feillet Manor in Brittany, grew up to marry René-Hiacinthe, the Marquis de Coëtlogon who served as Governor of Rennes in the ranks of Maréchal de France and descended from a family of 12th-century knights. Their proud houses were joined on July 3, 1664 and Péronelle-Angélique became a Marquise. In 1669, she conceived a child and, for reasons unknown, drank a lot of hot chocolate.

Then a new sensation in Paris, chocolate had arrived from Mesoamerica via Spain. From the early 1670s, chocolate attracted the attention of medical and mercantile communities that saw in it a potential goldmine. It was hailed in medical treatises as a potent drug whose biological effects could not be entirely separated from its foreignness. Presented as a sophisticated cure whose misuse could cause pain or worse, chocolate was tainted by concerns about excess and magical power. No wonder Paris eagerly sought it out. Before its effects on the body could be understood and fully separated from concerns about propriety, the high nobility self-medicated and enjoyed it with excited suspicion.

Madame de Sévigné talks several times about chocolate in her letters of 1671, and vehemently so during her daughter’s pregnancy, when she trots out the legend of Coëtlogon the Chocohaulic as a horrific cautionary tale:

“But what do you have to say about chocolate? Are you not afraid of how it can burn the blood? What if all the effects that appear miraculous mask some sort of diabolical combustion? What do your doctors say? In your fragile state, my dear child, I need your word [that you will not drink it], because I fear that you will suffer these problems. I loved chocolate, as you know. But I think it did burn me; and furthermore, I have heard many terrible stories about it. […] The Marquise de Coëtlogon drank so much chocolate when she was pregnant last year that she gave birth to a baby who was black as the devil and died.” (25 October 1671, translation mine)

Thus, the legacy of the ill-fated Marquise, about whom we know little else, was to have her greatest personal misfortune showcased in a story about the hazards of chocolate. The absurdity (not to mention latent racism) of the claim notwithstanding, Sévigné records a mentality that found thrill and danger in the exoticism of the foreign drink in the days before it became fashionable in Europe to overindulge in the pleasures of chocolate. In an odd twist of fate, Sévigné, who learned to love her hot cacao, was immortalized on the marquis of a maison de chocolat in 1898. Marquise de Sévigné chocolate shops still thrive in Paris today and her face circulates in silhouette on their signature morsels.

Christine A. Jones is Associate Professor of French and CLCS at the University of Utah.

February 3, 2015

Unhairing in the 1800s: Animal Processing and Personal Care

By Rebecca Herzig (Guest Contributor)

Prior to the mechanization of meat and leather production in the early nineteenth century, to strip a hide of hair was a gory and laborious process. Skins, covered with soil and blood, would be scrubbed clean of residual animal flesh. Hair was then softened and loosened by soaking the skin in urine, lime, or salt, and then scraped clean—“scudded”—by hand. The skin would then be pounded and kneaded, often with dung used as an emollient, and stretched and dried. Foul-smelling from the combination of urine, feces, and decomposing flesh, tanning operations were generally confined to the outskirts of towns, near moving water where waste could be dumped.

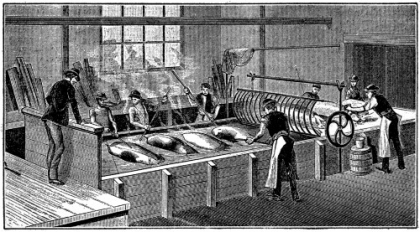

Pig Scalding

The increased rate of animal processing made possible by the advent of the “disassembly” line (a development recounted beautifully in Siegfried Giedion’s classic book, Mechanization Takes Command) prompted the need for faster, less labor-intensive techniques of “unhairing.” Many of the most effective new tools turned out to be chemical: alkalis such as lime (calcium hydroxide) and soda ash (sodium carbonate), and various combinations of sulfides, cyanides, and amines. Although noxious smelling and damaging to adjacent waterways, the novel chemical techniques of unhairing were hugely successful. By 1830, according to one agricultural journal, U.S. production of hides and skin was worth at least $30 million per year—roughly $3.5 million more than the country’s total cotton exports at the time.

The same chemical knowledge that advanced mass animal processing circulated among other early manufacturers, including the antebellum perfumers and druggists who bottled chemical depilatories for human application. As Andrew Ure’s influential industrial dictionary put it, compounds found to remove hair from hogs might equally strip hair from “the human skin,” and vice versa. Another antebellum technical manual, The Art of Perfumery, noted that the same packaged depilatories designed for “ladies” who consider hair on the upper lip “detrimental to beauty” would work equally well for “tanners and fellmongers” preparing hides and skins.

And, as commercial compounds increasingly displaced the homemade hair removers that women had long been making from ordinary kitchen ingredients, purchasers became increasingly unsure about just what they might be putting on their faces. Injuries were not uncommon. In 1804, one Boston weekly reported the case of a “dowager lady” who had rubbed a commercial depilatory around her mouth, removing the hairs yet “taking all the flesh with them.” The depilatory’s systemic effects damaged the woman’s eyes as well, which “obliged her, for some time, to use a black shade.” Other commentators warned about “the utmost risk to health, if not to life” posed by packaged hair removers. “Under all circumstances,” concluded the Journal of Health in 1831, “we believe it to be far better to put up with the deformity arising from the superfluous hair, than to endanger the occurrence of a greater evil by attempting its eradication.”

Although concern about the “evils” of corrosive or toxic depilatories persisted through the nineteenth century, commercial hair removers remained completely unregulated. Even today, debate over cosmetics regulation tends to focus on the health impacts on individual consumers, not on the more extensive ecological and social effects of cosmetics manufacture, distribution, consumption, and disposal. The history of hair removal illuminates some of those effects—the broad, unsettling consequences of seemingly insignificant acts of separating self from other.

Rebecca M. Herzig is the author of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal (New York University Press). Her previous books include Suffering for Science: Reason and Sacrifice in Modern America and, with Evelynn Hammonds, The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race from Jefferson to Genomics.

Rebecca M. Herzig is the author of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal (New York University Press). Her previous books include Suffering for Science: Reason and Sacrifice in Modern America and, with Evelynn Hammonds, The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race from Jefferson to Genomics.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on September 30 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

December Book Giveaways

Rebecca M. Herzig, “Plucked: A History of Hair Removal”

Michelle Moran, “Rebel Queen”

Seth Koven, “The Match Girl and the Heiress”

February 2, 2015

Parrots with Shocking Vocabularies

by Adrienne Mayor (regular contributor)

A great many exotic birds flocked to London in the seventeenth century, imported by the East India Company, retired sea captains, and sailors. The first mynah bird to reach England was a gift from the Company to the Duke of York in 1664. The Bengal mynah knew phrases in English and could neigh like a horse. Fashionable Londoners loved to stroll along Birdcage Walk in St James Park to admire the aviaries of hundreds of beautiful birds donated by the Company during the reign of Charles II.

Charles II, however, preferred to keep a tame British starling with an impressive vocabulary in his bedchamber. Samuel Pepys, the great diarist of the British aristocracy in the 1660s, later acquired the royal starling. Pepys exclaimed in his journal that “the king’s starling doth talk and whistle finely, which I am mighty proud of.”

Pepys also enjoyed his bevy of canaries, given to him by a sea captain, while his wife loved her garrulous parrot. “For talking and singing,” marveled Pepys, “I never heard the like!” Pepys was amazed when his neighbor’s parrot immediately recognized a new servant named Mingo, whom he’d known from a previous household. Pepys also described a bad-tempered parrot that almost pecked out the eye of a different friend.

Yet another parrot of Pepys’ acquaintance belonged to Lord Batten who “hath brought it from the sea.” Batten’s parrot often entertained guests at dinner parties. When Pepys visited the parrot was well behaved: “It speaks very well and cries Poll so pleasantly,” wrote Pepys. But Lady Batten and her mother detested Poll. It seems that Poll’s seafaring days had influenced its vocabulary in a vulgar manner–a typical problem with talking birds in general.

A similar case was described by Reverend Samuel Wesley of Epworth Rectory. This parrot lived in Billingsgate, the crowded, noisy street of fish markets frequented by sailors and fishermen notorious for their foul language. The parrot naturally developed a vast vocabulary of filthy phrases, cheerfully squawking out offensive insults and dirty slang to passersby. The owners, hoping to reform the bird, sent the him away to live in a genteel tea room across town. In less than a year the parrot’s bawdy expressions were replaced with inoffensive tea room chatter, along the lines of “What’s new?” and “Please bring another cup of coffee.”

Thus converted, the parrot was allowed to return home to Billingsgate. “But within a week,” the minister reported, “it had got all its wicked cursings and swearings down as pat as ever.”

Another cursing parrot appeared in a poem by George Crabbe (1809). In this tragic tale, a parrot lost his mistress’s favor and his life when he “was heard to speak / such frightful words as tinged his lady’s cheek.” The parrot, now stuffed, was replaced by a “clipped French puppy.”

At Andrew Jackson’s funeral in 1845, his pet parrot was hustled out for cussing. Then in New York City in 1938 a seafaring parrot named Popeye caused an uproar during a radio contest for talking birds. Some 1,200 contestants were judged on vocabulary, diction, and originality of expression. Entrants included an Italian fruit vendor’s African grey parrot who called out fruits in English; a 90-year-old Boston parrot who recited the Lord’s Prayer; and an Omaha parrot named Theodore Metcalf who barked, mewed, groaned, and gurgled. Popeye, who was sponsored by the NY Seaman’s Church Institute, was immediately disqualified for his salty vocabulary–despite his excellent diction and originality.

About the author: A research scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

January 31, 2015

Cabinet of Curiosities: xiii

By April Stevens (W&M Editorial Assistant)

Burned Scroll

“There is nothing new under the sun.” So they say, but in today’s rapidly changing times, some may question this biblical adage. Maybe our historical tidbits this week may help us to solve this conundrum.

Everyone knows the story of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, and after 2000 years, it’s old news, right? Wrong! Recently Italian Researchers discovered they could read the words on an ancient scroll discovered in Herculaneum with x-rays. Although they have only been able to make out a few words, the handwriting has given clues to the author’s identity and the team has hopes of reading more of the text using a more powerful x-ray machine.

Viking House in Hedeby

Perhaps you consider the issue of pollution to be a modern dilemma. Well, Danish researchers have found that fires used for cooking and heating in Viking-era homes would have caused significant indoor air pollution. High carbon monoxide levels could have give Vikings health issues such as chronic bronchitis and persistent headaches.

Rece ntly, laughing gas has been in the news headlines because it is now being offered to mothers during childbirth, but did you know laughing gas has a long history outside the dentist’s chair? Learn more about how laughing gas has been used in its 240 year history in Linda Rodriguez’s article “The Surprising History of Hippy Crack”.

ntly, laughing gas has been in the news headlines because it is now being offered to mothers during childbirth, but did you know laughing gas has a long history outside the dentist’s chair? Learn more about how laughing gas has been used in its 240 year history in Linda Rodriguez’s article “The Surprising History of Hippy Crack”.

What about the discussion of gender identity in our culture today, surely that is new? Sorry, but questions of gender identity have long been news items. Linton Weeks studies women who dressed, posed, and lived as men in 19th century in his article “‘Female Husbands’ in the 19th Century”.

So Readers, I leave the final verdict up to you: is there anything new under the sun? Please let us know your thoughts in the Comments below!

Still craving more history? Check out some of our recent posts:

The Incident of the Fly Swatter

Don’t forget to register for this month’s Book Giveaway here!

January 29, 2015

Start the New Year Off Right: Book Giveaway

Was one of your New Year’s resolutions to read more? It is not too late to get started! You still have until January 31st to sign up for our Monthly Book Giveaway.

This month we are excited to giveaway David Konstan’s Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. This book explores the contested concept of beauty, seeking answers to the question: what does it mean to say something is beautiful? This exploration of ancient Greek notions of beauty sheds light on modern esthetics.

This month we are excited to giveaway David Konstan’s Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. This book explores the contested concept of beauty, seeking answers to the question: what does it mean to say something is beautiful? This exploration of ancient Greek notions of beauty sheds light on modern esthetics.

Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on January 31st to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

December Book Giveaways

David Konstan, “Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea”

“We’re Still Here!”: Slang of the Roaring Twenties

By Joseph Wallace (Guest Contributor)

[image error]When you’re writing a historical novel, there’s one simple but crucial rule: Make sure the language rings true. Don’t , and your readers will be fleeing for the exits, laughing at you as they go.

Early on in researching my 1920s-set novel, Diamond Ruby, I learned that the slang of the era was extremely rich and risqué. People said, “Cash or check?” for “Do I kiss you now or later?” and “Bank’s closed” when the answer was a categorical no. A convertible car was a breezer, and a struggle buggy was a car with a back seat, where you…struggled.

Unsurprisingly, in the age of Prohibition, slang words for being drunk were everywhere. You weren’t merely tipsy, you were spifflicated, canned, corked, tanked, zozzled, owled, ossified, or fried to the hat.

So the source material was abundant (you can see more expressions here). The problem was using it. Every time I tried, it came across as stilted, silly, fake. As if each use carried invisible quotation marks.

I finally figured out why: Because 1920s slang did come with invisible quotation marks. It wasn’t an organic language. It was an invention, created by people whose goal was to forget the past and remake themselves.

The Roaring Twenties was, at heart, a child of the 1910s. All its wildness, the outlandish flapper fashions and headline-grabbing gangster capers and days-long parties were a reaction to two cataclysms of the previous decade: the long, brutal slog of World War I and the great influenza epidemic of 1918.

Those who survived both knew how lucky they’d been – and how fragile life was. Slang was just one small but crucial part of the frenetic seize-the-day spirit that followed.

This insight – that all this wonderful slang was created as a way of saying, “We’re still here!” – gave me the key to writing Diamond Ruby in the truest voice I could. In an essential way, it even allowed me to understand the madcap, tragicomic spirit of the time.

Joe Wallace has been fascinated by the Roaring Twenties since he first decided he wanted to go there and meet James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. He got to explore that world when he researched and wrote his first novel, Diamond Ruby, which is set in a 1920s New York City teeming with gangsters, rum-runners, and other colorful characters. He is currently at work on a Ruby sequel and an apocalyptic thriller definitely not set in that era.

January 26, 2015

The Incident of the Fly Swatter

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

(This post is the first on a series on the French in Algeria now up at History in the Margins.)

Shortly after the Charlie Hebo killings, I received an e-mail from a friend and regular reader of History in the Margins suggesting I write a post about the long, complex, and often difficult relationship between France and its Muslim citizens, hoping it would give her/you a context for the killings and their aftermath. I will admit that I hesitated. I’m a historian, not a political commentator.

But in fact, I feel strongly that the West in general and Americans in particular need to know more about the history of other parts of the world in order to understand how we got to where we are today, and more importantly to understand that no single perspective of the past is universally shared.

This is exactly the type of moment where some historical context might be useful. That said, I’m not going to give you a pundit-style analysis of current events. Instead, over the next several blog posts I’m going to tell you some stories about the French in North Africa and Muslim resistance to their presence, with perhaps a few detours that catch my attention. These are not intended as explanation for the recent events in France. They are simply pieces of the past that are part of the shared French and North African experience.

Let’s start at the beginning:

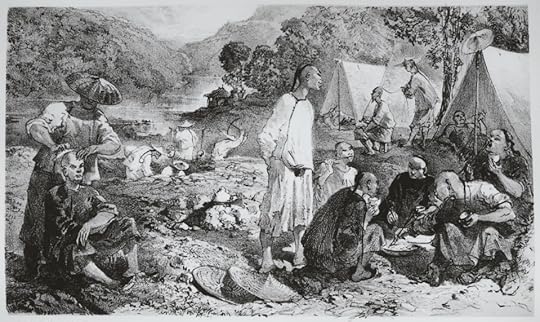

Anon. French illustration. I’d love to see its Algerian counterpart. Anyone?

In 1795, revolutionary France bought 8 million francs* of Algerian grain to feed its army. The French Republic failed to pay its debt, as did the French empire which succeeded it. When Napoleon was overthrown in 1815, the newly restored Bourbon monarchy disavowed the debt. From the French perspective, the matter was done but the Algerians weren’t willing to let it go. Not surprisingly, given the amount of money involved.

Despite ongoing negotiations, the matter was still unresolved by April, 1827 when a meeting between the Ottoman regent of Algiers, Hussein Dey, and the French consul, Pierre Duval, turned ugly Reportedly, when Hussein Dey pressed for an answer, Duval told him that France didn’t discuss money with Arabs. (!!!) The governor hit Duval in the face with the fly whisk that formed part of his regalia. The French press dubbed the incident “the affair of the fly-swatter”–a term that magnified the insult.

Charles X demanded an apology for the insult to his representative. When no apology was forthcoming, he sent French ships to blockade the harbor of Algiers–a”cut off your nose to spite your face” technique that limited French access to much needed Algerian grain for almost three years.

In June, 1830, tensions between Charles X and French republicans were coming to a head. The French king attempted to distract his detractors by accelerating tensions in Algeria. On June 12, 1830, using a plan originally developed by Napoleon, 34,000 French troops landed in Algeria. Three weeks later, Dey had fled into exile and the French military found itself the occupying power in coastal Algeria. France’s decades- long struggle to conquer North Africa had begun.

The invasion did nothing to help Charles X, who was forced to abdicate on July 30.

*How much is that in today’s money? Good question, and not easily answered. The short answer is billions, if not gazillions.

If anyone knows of a good resource for translating 18th century francs to 21st century dollars, let me know. I spent way too much time chasing this down the rabbit hole. Eventually I found a site that gave me a conversion rate between francs and pounds sterling in the 1780s (1 pound =23 livres and a bit), then a site that gave me a rate for converting pounds to dollars in 1795 (1 pound=$4.53), and finally a site that gave me the relative worth of American dollars from 1795 and 2013. The answer ranged from $28,200,000 to $68,900,000,000–depending on the measures you use. (If you’re interested in the possibilities, I refer you to MeasuringWorth.com.) And that’s not even taking into account my own questionable methodology in sliding from 1780s values to 1795.

January 22, 2015

Los Angeles Chinese Massacre, 1871

By Scott Zesch (Guest Contributor)

A typical 19th century Chinese Mining Camp

The word “massacre” usually brings to mind lonely American landscapes such as Wounded Knee, Mountain Meadows and Sand Creek—not a busy metropolis like Los Angeles. Yet that city’s first race riot, dating back all the way to 1871 and largely forgotten today, came to be known as the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre.

At the time it occurred, Los Angeles was a Wild West town of only 6,000 residents. Most people outside of California had never heard of it. Californians knew about the place mainly because it had the state’s highest per capita murder rate and largest number of lynchings.

Shortly before sundown on October 24, 1871, a gunfight broke out between members of rival Chinese factions. Angelenos ran to Chinatown to see what was happening. A reckless white rancher discharged his revolver into a Chinese store and was killed by return fire. Within a short time, an angry crowd of about 500 Anglos and Latinos gathered in the streets of Chinatown, surrounding the low adobe buildings. As darkness fell, the Chinese were trapped inside their homes and shops. After a three-hour standoff, the mob broke into the Chinese headquarters, seized random victims, and dragged them off to be hanged. Eighteen Chinese men were murdered that night.

This half-hour killing spree was the bloodiest attack on Chinese immigrants the country had experienced at that time. The Chinese Massacre was also the first event to draw nationwide attention to Los Angeles. It was a public relations disaster for the small but growing town, whose civic leaders were careful not to mention the atrocity in a local history they published five years later. Today, a small plaque near the Hollywood Freeway is all that commemorates the city’s first deadly racial uprising and one of America’s worst hate crimes.

Scott Zesch is the author of The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 (Oxford University Press). His previous book, The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier, won the TCU Texas Book Award.

January 20, 2015

Five Tips on Giving a Talk about History

By Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Over the past twenty years, I’ve given talks about history — usually on topics connected to the subjects of my books — throughout North America and in Europe. Most of my talks have taken place in undergraduate and graduate-level academic settings, although I’ve also addressed medical and history conferences, schoolchildren, business audiences, book clubs, and cultural groups.

Booker T. Washington addresses an audience in Carnegie Hall, New York City, 1906

Talking about history is an acquired skill. I’ve grown adept at making quick adjustments for the needs and interests of the audience as well as for the quirks of the setting. For those of you contemplating a history talk, I offer these five tips:

Arrive early — not just to avoid being late, but also to take in what’s preceding your talk. If other speakers are giving talks before yours, you’ll do your audience a service if you can link your topic with those of the earlier speakers. Much of understanding history, after all, is about connecting the dots. Help your audience make illuminating connections.

Don’t read. Book authors often believe that they must read out loud from their pages, but doing so puts people to sleep. Audiences, who are often as interested in learning about you as your writing, want to understand your historical obsessions. Let the book speak for itself and give the audience an intriguing story about your path to writing it. When I talk about The Nazi and the Psychiatrist , I often tell the tale of how I found the documents upon which I based the book.

Avoid unclear language. The study of history is full of jargon favored by specialists or indicative of lazy thinking. Don’t use it. I make a point of eliminating from my talks the terms I call “The Evil I’s” — the various forms of the words impact, inform, and issue — in the interests of clarity and directness. You can form your own hit list of terms.

Customize your talk. Speaking to a conference of neurosurgeons about my book The Lobotomist , for example, I focus on the historical developments in brain surgery that accompanied lobotomy. Business audiences are intrigued by the speculations of Dr. Douglas M. Kelley — the central figure in The Nazi and the Psychiatrist — on the similarities between the Nazi leadership hierarchy and the organization of corporations.

Let your audience teach. We all know to ask for questions from the audience, but a skilled history speaker will go further by directing questions to the audience. A standard feature of my talks about The Lobotomist and the history of psychosurgery is my call for stories from the audience about their experiences with psychiatric surgery. People have risen to give the most amazing personal accounts — many of which I wish I could have included in my book — and one person even displayed a set of lobotomy tools she had brought with her. (Her father was a psychosurgeon.)

Exemplary history talks:

Roach, Mary. 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Orgasm.

Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

For the Love of Art

By Heather Webb (Guest Contributor)

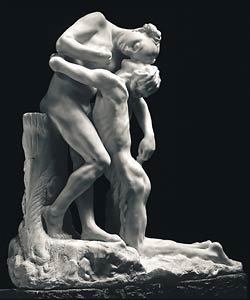

Sakantula

Being a female artist in Belle Époque France was a challenge to say the least, yet young sculptor Camille Claudel would carve out a name for herself—at all costs. Attending proper art school with nude models was frowned upon, and in most cases forbidden, as was wearing trousers to do the intense lifting, scrubbing, and chiseling that came with being a sculptor. To make matters worse, women seldom won the coveted positions at the Champs-Elysée Salon. On the rare occasion a female artist was nominated for her work, she garnered lesser awards, leaving the prestigious Salon prizes for their male counterparts—allegedly the most creative and intelligent of the sexes.

Yet Camille managed all of these feats. Not only did she work with live, nude models, but she received commissions for her work, as well as a prominent award for her sculpture Sakuntala; a depiction of an Indian woman resting her head atop her lover’s, who pleaded for her forgiveness. Still, Camille’s sensual work was deemed indecent by many, and her Sakuntala (among other pieces) was not accepted everywhere.

The Wave

On one occasion in 1895, Camille sold an Alexander Harrison painting she owned to a museum in Châteauroux to support herself—buying stone, clay, and tools for sculpting, never mind rent for her atelier that cost a small fortune, and she, among other artists struggled to make ends meet. Camille was so relieved by the museum’s purchase that she donated a copy of Sakuntala to the museum as a thank you. Delighted, the art committee featured her work in the main hall.

Camille visited the museum to view how they displayed her piece, and received a warm welcome, prompting the committee to submit an article praising her work in the town newspaper. Once again, Camille met strife. Several conservative bourgeois from the town were shocked—as other critics in Paris had been—by the sensual nature of her work. They pushed back against her and the art committee, ridiculing her skills and making both sexual jokes about the Hindu legend she had depicted, as well as mocking the committee for their choice in showing it. One article even suggested hiding the sculpture behind a curtain.

Clotho

Luckily for Camille, she had gained the support of a few well-known critics who came to her defense. Gustave Geoffroy said, “Those who saw [Sakuntala] retain in their memory…the anatomical science and the passionate expression of these two figures.” Rodin, Camille’s collaborator, teacher, and lover, offered his unfailing support of her as well.

In my novel Rodin’s Lover, I explore the politics of art, the tumultuous affair between the famed Auguste Rodin and his volatile, yet brilliant student Camille Claudel, and the fine lines between obsession and madness.

For those interested in seeing some of Camille’s works, a few of my favorites are: The Waltz, The Wave, Maturity, The Gossips, and Clotho. I have photos on my website under FOR FUN, as well as a Pinterest board packed with photos of her work as well as Rodin’s.

Heather Webb is the author of historical novels Becoming Josephine, Rodin’s Lover, and A Fall of Poppies: An Anthology of Armistice Day to be released from HarperCollins in 2016. In addition, she is a freelance editor and contributor to award-winning writing sites WriterUnboxed.com and RomanceUniversity.org. Heather is a member of the Historical Novel Society and the Women’s Fiction Writers Association.

Heather Webb is the author of historical novels Becoming Josephine, Rodin’s Lover, and A Fall of Poppies: An Anthology of Armistice Day to be released from HarperCollins in 2016. In addition, she is a freelance editor and contributor to award-winning writing sites WriterUnboxed.com and RomanceUniversity.org. Heather is a member of the Historical Novel Society and the Women’s Fiction Writers Association.

Do you like free books? Don’t forget to sign up for our monthly book giveaway. Please keep in mind that we can only ship to US addresses at this time.

Monthly Book Giveaway

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

December Book Giveaways

David Konstan, “Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea”