Holly Tucker's Blog, page 42

December 15, 2014

The Amazing Adventures of Marie Mancini’s Bed

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

The age of tourism started in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when improved roads, communications systems, and comfortable carriages began to make it possible for people of means to contemplate traveling for pleasure, and to see the sights of famous cities outside of their own countries. Rome was a big destination. Guidebooks began to appear in print, instructing enthusiastic young travelers on what was not to be missed on a visit to the holy city. In addition to some of the destinations like the Coliseum and the Vatican, early guidebooks directed young voyagers to the homes of prominent citizens. While they were paying their respects, they were advised to ask to see some of the more spectacular items in the house.

Furniture Tourism

In late seventeenth-century Rome, one such destination was the Palazzo Colonna, the home of the Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna and his wife Marie Mancini Colonna. The couple were important art patrons in Rome. They commissioned works by the best artists, including the famous sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini, to decorate their home. When in 1662 Marie became pregnant with her first child, her husband went to Bernini’s workshop to order a new bed, where his wife could lounge and receive visitors before and after the childbirth.

In late seventeenth-century Rome, one such destination was the Palazzo Colonna, the home of the Prince Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna and his wife Marie Mancini Colonna. The couple were important art patrons in Rome. They commissioned works by the best artists, including the famous sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini, to decorate their home. When in 1662 Marie became pregnant with her first child, her husband went to Bernini’s workshop to order a new bed, where his wife could lounge and receive visitors before and after the childbirth.

In her memoirs, Marie described the resulting marvel of furniture design that became a tourist destination almost as soon as it was unveiled:

In her memoirs, Marie described the resulting marvel of furniture design that became a tourist destination almost as soon as it was unveiled:

“The novelty as well as the magnificence of this bed filled everyone with admiration: it was a sort of seashell which seemed to float in the middle of an artfully represented sea, which served as a base for it. It rested on the hindquarters of four sea horses mounted by mermaids; the whole thing was admirably sculpted … Ten or twelve little cherubs served as attachments for curtains of a very rich gold brocade … “.

The Fallen Amazon

Travel guides written in the late 1600s and early 1700s continued to advise travelers to go and look at the bed, and engravings of it circulated like postcards. But the bed became famous in ways that Lorenzo Colonna could not have anticipated, when his wife, in 1672, ran away from her husband and her unhappy marriage to begin a life on the road, never to return. In taking this scandalous and extraordinarily bold step Marie also left behind her three sons, who were never permitted to join her, despite her repeated pleas to her husband to let them leave Rome to be with her.

Though the runaway mother eventually reestablished contact with her sons, they must have felt some resentment toward her that they never could overcome. Filippo, the eldest, inherited the Roman family palazzo along with its lavish contents, including the bed where he had been born. The bed made a famous reappearance on the stage in the great hall of the family residence in 1689, when Filippo and his wife hosted the performance of a new opera. The opera, called ‘The Fall of the Reign of the Amazons’ , featured a scene where the Amazon queen reclined on a fabulous bed, the bed of Filippo’s mother Marie Mancini. A new generation of tourists came to see the opera and the famous piece of furniture that was its centerpiece.

Though the runaway mother eventually reestablished contact with her sons, they must have felt some resentment toward her that they never could overcome. Filippo, the eldest, inherited the Roman family palazzo along with its lavish contents, including the bed where he had been born. The bed made a famous reappearance on the stage in the great hall of the family residence in 1689, when Filippo and his wife hosted the performance of a new opera. The opera, called ‘The Fall of the Reign of the Amazons’ , featured a scene where the Amazon queen reclined on a fabulous bed, the bed of Filippo’s mother Marie Mancini. A new generation of tourists came to see the opera and the famous piece of furniture that was its centerpiece.

A lounge for a hermit

Later editions of guidebooks to Rome in the eighteenth century continue to mention the bed, but only to say that it seemed to have fallen in disrepair and was no longer able to be viewed. Travelers continued to try to catch a glimpse of it, though, as they toured the Colonna Palace. Speculation was that it’s skeletal remains could be found in another decorative corner of the residence, a private retreat designed as an escape from the busy pressures of socializing. Now the bed was just a simple wooden structure decorating this room called a ‘hermitage’ within the palace, a peaceful corner where the wealthy residents could hide from the pressures of the world.

There is nothing left of the famous bed today, but travelers to Rome may still visit the Colonna Palace on designated weekend hours, to admire the magnificent home that is still a private residence, now occupied by Marie and Lorenzo’s descendants.

The Memoirs of Hortense and Marie Mancini, edited and translated by Sarah Nelson (2007).

Elizabeth C. Goldsmith, The Kings’ Mistresses: The Liberated Lives of Marie Mancini, Princess Colonna and her Sister Hortense, Duchess Mazarin (2012).

Joan DeJean (on ‘furniture tourism’), The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual and the Modern Home Began (2009).

December 11, 2014

The Emperor and the Ape

By Lars Brownworth (Guest Contributor)

On the night of December 24, 820 the furious emperor Leo V sentenced his old drinking buddy to death and started in motion one of the most bizarre events in Roman history. The 45-year-old emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire- dismissively labeled ‘Byzantine’ by later historians- had good reason to be upset. It was Christmas Eve and instead of attending a comfortable banquet in the palace he was stuck in an audience chamber listening to evidence that his best friend was plotting to assassinate him. Not quite believing the news, he had the man in question- Michael the Amorian- dragged in front of him, and was stunned to hear a full confession.

As disbelief turned to rage, the emperor screamed out his sentence. Mere execution was too good for this traitor; he had to be humiliated in the process. Michael was to be tied to an ape and hurled into the furnace that heated the imperial palace.

Much to the ape’s relief, a night in the dungeon was enough to focus Michael’s supporters. Early Christmas morning they snuck into the palace chapel dressed as monks, and when Leo arrived to celebrate the Mass they rushed at him. The emperor managed to grab a heavy metal cross and give a good account of himself, but the struggle was soon over. Michael was hastily brought up from the dungeons and- in what was surely the most undignified coronation in history- crowned with the iron chains still on his legs.

Though time has not been kind to the Byzantines, you can still see the spot where Michael was crowned today. It’s in the cavernous cathedral of the Hagia Sophia, a building by itself well worth a trip to Istanbul, Turkey. Marked out by a geometric design in the polished marble floor, the spot offers a brief glimpse at the splendor that awaited a successful claimant of the throne.

That is of course if you could survive the attempt.

Lars Brownworth is the author of Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization , is a former history and political science teacher at Stony Brook High School in Long Island, NY, a speaker and a broadcaster. He is also the creator, along with his brother Anders, of the genre-defining top 50 podcast, 12 Byzantine Rulers: The History of the Byzantine Empire. He currently resides in Maryland with his wife. Read more about Lars here.

, is a former history and political science teacher at Stony Brook High School in Long Island, NY, a speaker and a broadcaster. He is also the creator, along with his brother Anders, of the genre-defining top 50 podcast, 12 Byzantine Rulers: The History of the Byzantine Empire. He currently resides in Maryland with his wife. Read more about Lars here.

IMAGE: The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 September 2009.

December 9, 2014

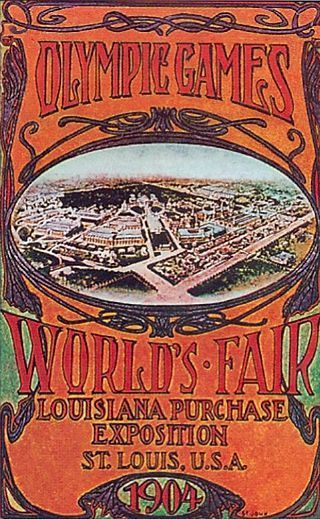

How St. Louis Stole the 1904 Olympic Games

By Matthew D. Plunkett (Guest Contributor)

“Everything settled. You have Olympic Games.”

Baron Pierre de Coubertin sent this telegram in February 1903 and awarded the city of St. Louis the right to host the 1904 Olympic Games. Yet nearly two years earlier, in May 1901, Coubertin and the International Olympic Committee voted to award the same Olympic Games to Chicago.

Somehow St. Louis stole the Olympics.

Although Chicago won the original bid, St. Louis immediately set out to undermine its planning efforts. Already slated to host the 1903 World’s Fair, St. Louis’ ambition grew, and it quickly made the decision to steal the Olympics.

After securing $6 million in funding and delaying the opening of the World’s Fair for one year, St. Louis set out to persuade James Sullivan and the Amateur Athletics Union (AAU) to hold its national track and field championships in St. Louis in the summer of 1904. Founded prior to the NCAA, the AAU was the premier athletic association in the country and held tremendous sway over its athletes.

After securing $6 million in funding and delaying the opening of the World’s Fair for one year, St. Louis set out to persuade James Sullivan and the Amateur Athletics Union (AAU) to hold its national track and field championships in St. Louis in the summer of 1904. Founded prior to the NCAA, the AAU was the premier athletic association in the country and held tremendous sway over its athletes.

Dubbed “America’s first sports czar,” Sullivan’s cooperation was essential. An IOC member once described Sullivan as “…a man whose great faults are those of his birth and breeding, but he…..holds the organized athletes of the clubs in the hollow of his hand.” If Sullivan collaborated with St. Louis, Chicago would lose the centerpiece of its Olympics because America’s best athletes would be in St. Louis. Given that Sullivan viewed Coubertin as “a powerless, pathetic figure in charge of an inept committee,” the decision to cooperate with St. Louis was most likely an easy one.

Using the combination of its financial backing and its willingness to use America’s athletes as leverage, St. Louis outflanked and outmaneuvered its northern rival. Chicago had only three choices: continue with the Olympics as planned but without America’s best athletes; transfer the Games to St. Louis; postpone the Olympics until 1905. Meekly, Chicago asked Coubertin to make the final decision.

Baron de Coubertin read the writing on the wall. In February 1903, he alerted Chicago of his decision. With two words, Coubertin wiped out two years of planning: Transfer accepted.

Whereas prior Olympics were covered by newspapers only in the northeast, the drama surrounding the transfer of the 1904 Olympics was covered far and wide. Readers’ interest in the story spurred further coverage even after the location of the Games was settled. As a result, Americans came to learn about the modern Olympic movement, its roots in antiquity and the prospect of the Olympics taking place on American soil. The intrigue surrounding the 1904 Olympics laid the groundwork for the popularity of the Games in America today.

And while Chicago continues to dominate the Midwest in population, economic output and cultural relevance, St. Louis can always recall when it swiped the Olympics from its big brother to the north.

Sources:

Mark Dyreson, Making the American Team: Sport, Culture, and the Olympic Experience, University of Illinois Press, 2008.

George R. Matthews, America’s First Olympics: The St. Louis Games of 1904, University of Missouri Press, 2005.

John J. McAloon, This Great Symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games, Routledge, 2007.

Stephen Pope, Patriotic Games: Sporting Traditions in the American Imagination, 1876-1926, Oxford University Press, 1997.

“Born From Dilemma: America Awakens to the Modern Olympic Games, 1901-1903,” by Robert Knight Barney, Olympika: The International Journal of Olympic Studies, Vol. I, 1992, pp. 92-135. http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/Olympika/Olympika_1992/olympika0101f.pdf.

“Coubertin and Americans, Wary Relationships, 1889-1925,” by Robert Knight Barney. In Norman Mueller (ed.), Coubertin and Olympism: Questions for the Future. Report of the Congress at the University of Le Havre, September 17-20, 1997. Lausanne: Comite International Pierre de Coubertin.

http://www.coubertin.ch/pdf/PDF-Dateien/112-Barney.pdf

“Chicago Loses the 1904 Olympics,” by John E. Findling, Journal of Olympic History, Journal of Olympic History, 12(October 2004)3, pp. 24-29. http://www.isoh.org/articles/16-chicaco-loses-the-1904-olympics/.

“Olympians Games for Chicago.” The New York Times, March 25, 1901

“St. Louis Gets Olympic Games.” The New York Times, February 12, 1903

“Front Page-No Title.” The New York Times, August 25, 1896

Matthew D. Plunkett is a history teacher and writer living in New York City. In addition to his historical writing, Matthew is currently working on a project about the Sunderland Football Club of the Barclay’s Premier League.

December 8, 2014

The Glory that was Greece?

by Helen King

Crespi, Amore e Psiche

Beneath the most quoted lines, there can be a surprising story…

When we study the ancient Greeks and Romans, we are always having to tread a fine line between familiarity and distance. If they are people just like us, then we feel that we can easily understand the nuance of a line of poetry, or appreciate an image on a vase: but if they are totally different from us, then how can we ever claim to understand them at all?

Historically, western culture has identified very strongly with the Greco-Roman world; ‘the glory that was Greece’, in particular, has been appropriated as the origin of much that is familiar to us now, including science, philosophy, democracy, art and architecture, poetry and drama. But other aspects of the classical world have not been greeted with the same enthusiasm. From polytheism and animal sacrifice to gladiatorial combat, and from infanticide to slavery, some features of Greek and Roman society now feel very alien, and if we choose to focus on these then the Greeks and Romans may look to the modern viewer more like the dangerous Other than our honored ancestors.

There’s an interesting phrase that resonates through the history of studying the classical world: ‘the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome’. Mary Beard and John Henderson, in their useful book Classics: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), attribute the lines to the original version of Edgar Allan Poe’s 1831 poem To Helen. But in fact the original version had the rather less gripping wording, ‘the beauty of fair Greece, and the grandeur of old Rome‘.

What was this poem To Helen about? It imagines the beauty of Helen of Troy, as you may expect, but was written for a real woman: Jane Stanard, the mother of one of Poe’s friends, who died in 1824. She encouraged his early work, and Poe later described her as ‘the first, purely ideal love of my soul’ (Mabbott, 1978: 164).

The poem became well-known through its inclusion in the Oxford Book of English Verse. The story of that collection of poetry is itself very interesting (and timely for the year of the anniversary of the outbreak of WW1). It was edited by the classically-trained Arthur Quiller-Couch, whose son Bevil fought in the war, survived the trenches, including such terrible battles such as those of Mons and Ypres, but died in the influenza pandemic on 6 February 1919.

In their familiar form, these lines in fact come from a revision of the poem made in 1843. In a further example of our changing evaluations of the past, Beard and Henderson label the poem ‘dreadful and forgotten’ whereas for Poe’s 1941 biographer Arthur Hobson Quinn it was not only ‘oft-quoted’ but ‘one of the most exquisite tributes ever paid by man to woman’.

In the poem, Jane is not only compared to Helen, but also to Psyche. In myth, Psyche was loved by Eros, but he came to her in darkness so she did not know who her lover was. One night she waited until he was asleep, then lit a lamp to reveal that her lover was in fact a god, as you’ll see in the image at the top of the page (personally I think Eros’ wings would have given Psyche a clue, if she’d thought about it…). In the myth, Psyche is very much the innocent – it seems like a reversal of the situation with the boy Edgar and his friend’s mother Jane. What do you think? Is this a poem about intellectual ‘beauty’ or something physical? Does Edgar have a serious crush on Jane? Is he in love with her, or with the ‘Holy Land’ which here represents ancient Greece and Rome?

Here’s the complete poem:

HELEN, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicæan barks of yore,

That gently, o’er a perfumed sea,

The weary, wayworn wanderer bore

To his own native shore.

On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs, have brought me home

To the glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.

Lo! in yon brilliant window-niche

How statue-like I see thee stand,

The agate lamp within thy hand!

Ah, Psyche, from the regions which

Are Holy Land!

To find out more:

The best place to start thinking about our approach to the ancient Greeks and Romans remains Paul A. Cartledge, The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993)

For Poe, see Thomas O. Mabbott, Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978): http://www.eapoe.org/works/mabbott/to...

and Arthur Hobson Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1941)

The glory that was Greece?

by Helen King

Crespi, Amore e Psiche

Beneath the most quoted lines, there can be a surprising story…

When we study the ancient Greeks and Romans, we are always having to tread a fine line between familiarity and distance. If they are people just like us, then we feel that we can easily understand the nuance of a line of poetry, or appreciate an image on a vase: but if they are totally different from us, then how can we ever claim to understand them at all?

Historically, western culture has identified very strongly with the Greco-Roman world; ‘the glory that was Greece’, in particular, has been appropriated as the origin of much that is familiar to us now, including science, philosophy, democracy, art and architecture, poetry and drama. But other aspects of the classical world have not been greeted with the same enthusiasm. From polytheism and animal sacrifice to gladiatorial combat, and from infanticide to slavery, some features of Greek and Roman society now feel very alien, and if we choose to focus on these then the Greeks and Romans may look to the modern viewer more like the dangerous Other than our honored ancestors.

There’s an interesting phrase that resonates through the history of studying the classical world: ‘the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome’. Mary Beard and John Henderson, in their useful book Classics: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), attribute the lines to the original version of Edgar Allan Poe’s 1831 poem To Helen. But in fact the original version had the rather less gripping wording, ‘the beauty of fair Greece, and the grandeur of old Rome‘.

What was this poem To Helen about? It imagines the beauty of Helen of Troy, as you may expect, but was written for a real woman: Jane Stanard, the mother of one of Poe’s friends, who died in 1824. She encouraged his early work, and Poe later described her as ‘the first, purely ideal love of my soul’ (Mabbott, 1978: 164).

The poem became well-known through its inclusion in the Oxford Book of English Verse. The story of that collection of poetry is itself very interesting (and timely for the year of the anniversary of the outbreak of WW1). It was edited by the classically-trained Arthur Quiller-Couch, whose son Bevil fought in the war, survived the trenches, including such terrible battles such as those of Mons and Ypres, but died in the influenza pandemic on 6 February 1919.

In their familiar form, these lines in fact come from a revision of the poem made in 1843. In a further example of our changing evaluations of the past, Beard and Henderson label the poem ‘dreadful and forgotten’ whereas for Poe’s 1941 biographer Arthur Hobson Quinn it was not only ‘oft-quoted’ but ‘one of the most exquisite tributes ever paid by man to woman’.

In the poem, Jane is not only compared to Helen, but also to Psyche. In myth, Psyche was loved by Eros, but he came to her in darkness so she did not know who her lover was. One night she waited until he was asleep, then lit a lamp to reveal that her lover was in fact a god, as you’ll see in the image at the top of the page (personally I think Eros’ wings would have given Psyche a clue, if she’d thought about it…). In the myth, Psyche is very much the innocent – it seems like a reversal of the situation with the boy Edgar and his friend’s mother Jane. What do you think? Is this a poem about intellectual ‘beauty’ or something physical? Does Edgar have a serious crush on Jane? Is he in love with her, or with the ‘Holy Land’ which here represents ancient Greece and Rome?

Here’s the complete poem:

HELEN, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicæan barks of yore,

That gently, o’er a perfumed sea,

The weary, wayworn wanderer bore

To his own native shore.

On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs, have brought me home

To the glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.

Lo! in yon brilliant window-niche

How statue-like I see thee stand,

The agate lamp within thy hand!

Ah, Psyche, from the regions which

Are Holy Land!

To find out more:

The best place to start thinking about our approach to the ancient Greeks and Romans remains Paul A. Cartledge, The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993)

For Poe, see Thomas O. Mabbott, Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978): http://www.eapoe.org/works/mabbott/to...

and Arthur Hobson Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1941)

December 7, 2014

How I Write History…with Jack El-Hai

An Interview with Jack El-Hai (Regular Contributor)

An Interview with Jack El-Hai (Regular Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: Two of your books, including your newestThe Nazi and the Psychiatrist, delve into medical history. Do you find that writing medical history differs from other histories you have written?

El-Hai: Stories from the history of medicine are often high-stakes narratives — they’re tales of life and death. And medical stories are inherently dramatic. Will the patient get better? Will the physician succeed? What is the cause of the medical problem, and which treatments might work? Just as important to me are these questions: What motivates the physician/investigator? Which of the physician’s passions and shortcomings will affect the investigation? The answers are, with luck, the stuff of tragedy and comedy.

Writing about medical history is different from other kinds of historical writing in one important way. I often find myself considering various aspects of patient privacy. If my research turns up the medical record of, say, a lobotomy patient from the 1950s, should I include in my writing that patient’s name and other identifying information? I’ve long struggled with this sort of situation, and I’ve discussed such matters matters of medical privacy with physicians, lawyers, and other writers. My conclusion, at least for now, is that I will not shrink from including identifying information on patients if it contributes to the narrative and the reader’s understanding of the story, and if I have determined that the patient is dead. If anyone is interested in reading more of my thoughts on this problem, see my recent article in Aeon.

W&M: What kinds of sources do you rely on when writing medical history? How do you find these sources?

Materials belong to the family of Dr. Douglas M. Kelley.

El-Hai: I’m a big archive hound and a worshiper of archivists. I have learned that so much of the best research material for nonfiction history stories awaits a lucky finder in government, academic, or other institutional archives. Generally, the best sources are not digitized or otherwise available online. When I’m considering a topic for a book, one of the first things I’ll do is go to archivegrid.org to see if any institution has collected manuscripts and other materials connected to my topic.

But that doesn’t mean I rely exclusively on materials in public archives. My book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist — which is about a U.S. Army psychiatrist’s examination of the top German leaders held for trial after World War II — is based on a unique collection of Dr. Douglas M. Kelley’s manuscripts, photos, and artifacts that his family has kept out of view for more than 60 years. I was astonished to learn of its existence and to dig deeply into it, because a great deal of its contents clearly are historically precious, flabbergasting, and revealing. I found the collection after a long and difficult search for Dr. Kelley’s remaining family members.

Interviews, when possible, are also essential to my research. I was very lucky to have tracked down the last two living people who worked with Dr. Kelley and the imprisoned German leaders at the Nuremberg jail. Both in their nineties, they gave wonderful interviews full of detail and vivid impressions of their work. Web searches led me to both men.

W&M: Can you tell us a little bit about the process you use to turn various primary sources into a reader-friendly historical account?

El-Hai: It’s more an approach than a process. I take a literary interest in historical events, which means that I’m compelled to focus on the people involved in history (we can call them characters) as well as their motivations. I’d never write a book about World War II, for instance, but I have written a book about a small group of people active in the war and the psychiatrist who studied them. One of my central questions is usually about what made the characters do what they did. Once I have developed two or three central questions, I build a story around the examination of the questions. How will I unspool the events in a way that intriguingly addresses my questions? What is the best factual tale I can construct to satisfyingly bring the reader to the final scenes?

I treat letters, journals, and other manuscripts as sources of thoughts, feelings, and motivations. Even business records and other seemingly dry manuscripts can contribute to character development. Throughout it all, I never fictionalize, invent thoughts, create composite characters, rearrange events, or write anything that cannot be supported by my sources and survive a thorough fact checking. One of my reasons for including extensive endnotes in my books is to send readers the message that I have not made anything up.

W&M: As a writer with different interests, how do you decide which stories you want to tell?

W&M: As a writer with different interests, how do you decide which stories you want to tell?

El-Hai: I keep a queue of ideas in my head, on my computer, and in my file cabinets. Most of the story ideas I like areconcerned with historical characters who have psychological conflicts or exhibit seemingly inexplicable behavior. These ideas can percolate for a long time until essential sources appear, I find a compatible buyer, or I come to understand what the narrative is really about. The Nazi and the Psychiatrist went 11 years from idea to book. I conceived my previous book, The Lobotomist, nine years before I wrote it.

I am patient and persistent because the passage of time only improves most of the stories that interest me. There’s no reason to rush. I’m not like a newspaper reporter who may feel pressure to break a story.

I know a story’s time has come when I grow obsessed by it, the sources have fallen into place, and I can explain the outline of the story to other people in a sentence or two. My mind then fills with its possibilities and my wife and children get sick of hearing me talk about it.

There’s one history narrative that I’ve been researching and developing since 1988. I came upon the story in a footnote. Everyone I interviewed for my research is now dead. This story isn’t a book yet, but I hope its time will soon come.

Jack El-Hai is a writer of books and articles who covers medicine, science, and history. His books include The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Dr. Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII (PublicAffairs Books, 2013; optioned for screen and stage by Mythology Entertainment), Nonstop: A Turbulent History of Northwest Airlines (University of Minnesota Press, 2013), The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness (Wiley, 2005), and many volumes of regional and business history.

December 4, 2014

The Party that Changed the World

By David King (Guest Contributor) Wouldn’t it be nice to have a clock that would slow down in times of pleasure and speed up in times of trial? That was once a wish of Austrian Emperor Francis I, who could certainly have used such a device in the autumn of 1814 when he opened his palace to a veritable royal mob who would never seem to agree, or leave. The occasion was the Congress of Vienna, a glittering peace conference at the end of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Wouldn’t it be nice to have a clock that would slow down in times of pleasure and speed up in times of trial? That was once a wish of Austrian Emperor Francis I, who could certainly have used such a device in the autumn of 1814 when he opened his palace to a veritable royal mob who would never seem to agree, or leave. The occasion was the Congress of Vienna, a glittering peace conference at the end of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

For a time, Vienna became the capital of Europe, the site of a massive victory celebration, and home to the most glamorous gathering since the fall of the Roman Empire. Never before have more kings, queens, and princes lived in the same place for such a long period of time.

Catering to the whims of these houseguests would sometimes be exasperating. Vienna wits soon poked fun at the early impressions made by the crowned heads who would so readily accept Emperor Francis’s generosity:

The Emperor of Russia: He makes love for everyone.

The King of Prussia: He thinks for everyone.

The King of Denmark: He speaks for everyone.

The King of Bavaria: He eats for everyone.

The King of Württemberg: He eats for everyone.

The Emperor of Austria: He pays for everyone.

In the end, after nine months of negotiations, celebrations, and intrigues, the Congress of Vienna would finally wrap up, drastically reconfiguring the balance of power and ushering in a modern age.

David King is author of Vienna 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War, and Peace at the Congress of Vienna and Finding Atlantis: A True Story of Genius, Madness, and an Extraordinary Quest for a Lost World.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 4 December 2008.

December 2, 2014

Shell Shock Hypnosis

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

War wounds take various forms, psychological wounds no less than disabilities resulting from obvious physical injury or amputation. During the First World War, many soldiers without detectable physiological damage nonetheless presented with physical symptoms, their bodies trembling, jerking or contorted as a consequence of “traumatic” experiences. In Britain, this condition became known as ‘shell shock.’

War wounds take various forms, psychological wounds no less than disabilities resulting from obvious physical injury or amputation. During the First World War, many soldiers without detectable physiological damage nonetheless presented with physical symptoms, their bodies trembling, jerking or contorted as a consequence of “traumatic” experiences. In Britain, this condition became known as ‘shell shock.’

Hypnotic cures

Treating and curing these conditions in order to return soldiers to effective service was a challenge taken up on both sides of the conflict by psychiatrists and neurologists eager to establish the reputation of their fledgling professions. For treatment, these doctors relied on a mish-mash of old techniques and experimental methods. In Britain and Germany, medical experts largely converged on the conviction that only psychological methods could treat conditions that resulted from emotional wounds.

One of the more controversial methods employed to treat shell shock was hypnosis. The Hamburg neurologist Max Nonne was the most prominent proponent of hypnosis treatment for war neurosis; although he was aware of the psychoanalytic approaches of colleagues in Vienna, his own motivation for hypnotizing patients was quite different from Sigmund Freud’s. Nonne did not wish to expose and release his patients’ inner unconscious, but rather to use hypnosis to take control of his patients’ bodies and restore them to health, like the inverse of a music-hall hypnotist who might convince a subject that they could not use their right leg, or that their hands were stuck together. Nonne was quite explicit about his use of medical power to discipline and impress his patients with his authority. In an article he wrote after the war, he admitted, “I always had patients undress to complete nakedness, since I found that one could thereby increase their feeling of dependence and helplessness.”

Shell Shock Cinema

A remarkable film was made of Max Nonne’s practice of curing patients through hypnosis, in Hamburg Eppendorf Hospital in 1916/17. It shows Nonne’s assistant stroking and manipulating the limbs of a series of hypnotized patients, re-enacting their earlier war neurosis symptoms. The film, ‘Funktionell-motorische Reiz- und Lähmungs-zustände und deren Heilung durch Suggestion in Hypnose,’ is approximately eleven minutes long, and shows a series of fourteen patients, both before and after treatment (the inter-titles inform the viewer), beginning with a patient suffering from severe stutter, through paralyses, to more spectacular walking disorders, in the case of the final patient, complete with full-body tremors and erratic head-jerking motions. In the film, each patient appears against a black background, dressed only in white underpants, and, with the exception of the first shot, which is a close-up of the head and shoulders of a patient with a serious stutter (presumably to highlight his stutter, as the film is silent), the patient’s entire body is shown.

The dominant figure in the film is the physician, who appears in each case, stroking and tapping the affected limbs, speaking to the patient, and occasionally, once the symptoms have disappeared, looking briefly into the camera, as if in triumph. The effect of the physician as a magician or puppeteer is heightened by a number of details, whether intentional or not, it is impossible to judge: firstly, the white coat the doctor is wearing is extremely long, making him appear improbably tall and seem to float against the black background, his hands ‘disappearing’ when his arms fall to his sides. Due to the way the film is edited, he also occasionally ‘pops’ into the picture and often appears from different sides of the screen in quick succession, adjusting and manipulating his patient’s limbs. Finally, the most striking scene in the film features the doctor supporting a patient by his arms, while the patient pedals round him in a circle with his one functioning leg, making the two appear like macabre, mismatched dance partners, led by the erect, white-coated doctor.

The full film was recently made available online by the German Federal Archive and can be viewed here:

Further Reading:

I write extensively about this and other ‘war neurosis’ films, about the legacy of Jean-Martin Charcot and Albert Londe, and about the connection between hypnosis/suggestion and cinema, in my forthcoming book.

For more on Max Nonne, his film and the German approaches to ‘shell shock’ in WWI, see Paul Lerner’s Hysterical Men: War, Psychiatry, and the Politics of Trauma in Germany, 1890–1930 (Cornell UP, 2003). On the medical response to war neurosis in Austria-Hungary, see Hans-Georg Hofer, Nervenschwäche und Krieg: Modernitätskritik und Krisenbewältigung in der österreichischen Psychiatrie (1880-1920) (Böhlau, 2004).

December 1, 2014

The Golden Fleece and the Argonauts

The origins of the oral traditions about the voyage of Jason and the Argonauts across the Black Sea to the land of golden treasure (ancient Colchis, modern Georgia) are uncertain. The tale evolved into an epic poem sometime before Homer (8th century BC). While the epic sailing expedition to find the Golden Fleece is an imaginary adventure set in the Bronze Age and features several magic and other mythic episodes, the story also contains many nuggets of historical, ethnographic, geographic, and natural realities. Greek travelers reached the far shores of the Black Sea at a very early date, since names from the languages of Colchis and the Caucasus are preserved in archaic Greek myths and appear in inscriptions on ancient Greek artifacts. For example, Apsyrtos, Medea’s brother, has an Abkhazian name, and Circe, the seductive sorceress in Homer’s Odyssey) means “The Circassian.”

WHAT WAS THE GOLDEN FLEECE?

The Golden Fleece sought by the Argonauts has been taken by scholars to merely symbolize the wealth of Colchis. But the true identity of the Golden Fleece was already recognized in antiquity, by the the natural historian Pliny. The meaning of the Golden Fleece was also understood by the geographer Strabo, a native of Pontus who had probably traveled to neighboring Colchis.

Appian (Roman historian born ca. AD 95), gives the fullest explanation of the local tradition that explains the Golden Fleece. People of western Colchis (Svaneti) submerged ram’s fleece in streams and rivers to collect gold grains and flakes carried down from the mountains. This ancient technique is still used by local mountain villagers in Svaneti. It is plausible that it was employed in the Bronze Age. Geologists today report that gold is still suspended in rivers of western Colchis. The fact that gold adheres to the fleece would have been discovered serendipitously when people washed new lambskins in rushing streams that contained plentiful gold flakes.

When Greek adventurers sailed to Colchis and reported on its golden treasures in archaic times, they may have repeated vague rumors about the mysterious “Golden Fleece,” as something unknown associated with the fabulous gold treasures of Colchis. Later Greek travelers heard explanations of the technique and then observed it firsthand. By the 7th century BC, Greeks had established trade colonies along the coast of Colchis in order to obtain the famous Scythian and Caucasian gold. Archaic Greeks were fascinated by the romance and mystery of “golden fleece” before they understood the technology.

This fleece technique was mystery to the Greeks because it only works in certain geographic/geological conditions, where rivers and streams are laden with gold sand eroding from high mountains bearing igneous rock with rich veins of gold. In the famous Scythian gold fields of the Central Asian deserts, for example, Bronze Age prospectors could not use the fleece method; they sifted sand for placer gold, brought down by erosion into dry gullies along the silk route below from the Altai (“gold”) Mountains.

GOLDEN FLEECE ARTIFACT

Among the small gold and bronze artifacts of rams of Colchis are what scholars describe as a curious “ram-bird” figurine (see image above), supposedly combining a ram’s head with a bird’s tail. But it seems obvious that this figure is not meant to depict a hybrid ram-bird. Instead it resembles a ram’s hide with the head attached, a common way to display and identify hides (think bearskin rugs with head attached). The texture on the hide indicates gold particles. The so-called ram-bird figurines likely represent the Golden Fleece.

About the author: A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014).

November 29, 2014

Ancient Fungi and the Future of Food

By Gastropod

Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past couple of years, you’ve probably heard about the human microbiome .

Research into the composition, function, and importance of the galaxy of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that, when we’re healthy, live in symbiotic balance in and on us has become one of the fastest moving and most intriguing fields of scientific study. But it turns out that plants have a microbiome too—and it’s just as important and exciting as ours.

In this episode of Gastropod, we look at the brand new science that experts think will lead to a “Microbe Revolution” in agriculture, as well as the history of both probiotics for soils and agricultural revolutions. And we do it all in the context of the crop that Bill Gates has called “the world’s most interesting vegetable”: the cassava.

We now know that we humans we rely on bacteria in our gut to help us digest and synthesize a variety of nutrients in our food, including vitamins B and K. There’s a growing body of evidence that the different microbial communities we host—in our guts, on our skin, in our mouths, and deep inside our bellybuttons—help protect us against disease and may even play a role in regulating mental health.

Mycorrhizal fungi growing on a petri dish in Alia Rodriguez’ lab. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, plants, including all the ones that we rely on to provide grains, vegetables, and fruit for our tables, have an equally tight relationship with microbes. And, as in humans, the symbiotic partnership between a plant and the microbes that lives on its leaves and roots and in the soil around it is utterly essential to the plant’s continued existence and health. Indeed, the very plant-ness of plants—their photosynthetic ability to harness light and transform it into food—comes from an ancient microbe that plants came to depend on so closely that they incorporated it into their own cells, transforming it into what we now know as a chloroplast.

But, despite its importance to their (and thus our) survival, the plant microbiome is perhaps even less well understood than its human equivalent. The main way in which scientists study such tiny creatures is by growing colonies of a particular microbe on a petri dish in a lab. But researchers estimate that only about 1 percent, the tiniest sliver of the plant world’s microbial citizens, can be cultured that way.

High-tech tools such as metagenomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics help researchers take a snapshot of the genetic diversity of life in a given bit of soil. But it’s still incredibly difficult to tease out exactly which bacteria or fungus performs what function for a given plant. Janet Jansson, whose lab at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is studying the role of soil microorganisms in the cycling of carbon, calls this great unknown “the earth’s dark matter.” She’s part of a new venture called the Earth Microbiome Project, an international collaboration of scientists working to understand microbial communities in soils all around the world.

While researchers scramble to map and analyze the plant and soil microbiomes, companies have sensed that there’s money to be made. When it comes to the human microbiome, processed food giants have started adding probiotics and prebiotics to everything from frozen yogurt to coconut water. In the field, scientists, small biotech companies, and agricultural behemoths such as Monsanto are all racing to develop probiotics for plants: learning from bacteria and fungi to develop supplements that can help crops grow better, using less fertilizer and pesticide, even in challenging environmental conditions.

Mycorrhizal fungi. Photo courtesy of Ian Sanders.

In this episode, Gastropod hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley focus on one particular kind of microbe: mycorrhizal fungi. These are ancient fungi that are believed to have lived on plant roots ever since plants first moved onto land, and they still co-exist with and support 80 percent of all plant species on the plant. We meet British scientist Ian Sanders, whose career has been devoted to studying mycorrhizal fungi genetics. Sanders’ latest big idea is that, by breeding better mycorrhizal fungi, he can help plants grow more food. He’s been working with agronomist Alia Rodriguez to test this theory in the cassava fields of Colombia, and we join him to find out his astonishing, as yet unpublished, results. Can the Microbe Revolution live up to its promises, out of the lab and in the field?

Along the way, we discuss other research into plant microbes, some of which has already been commercialized. For example, Rusty Rodriguez, head of a company called Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, has scoured extreme environments to find fungi that can help plants survive heat, cold, drought, and floods. During trials, AST’s new product, BioEnsure, which was released onto the market this fall, enabled crops planted during the 2012 drought in the American Midwest to produce 85 percent more food than untreated ones.

With early results like these, microbes are being called the next big thing in agriculture. There’s plenty of hype: Monsanto’s BioAg Alliance claims to be “rewriting agricultural history,” the American Academy of Microbiology recently issued a report titled “How Microbes Can Help Feed the World,” and even normally sober scientists have declared that this research may well “precipitate the second Green Revolution.”

But the first Green Revolution has plenty of critics, and the process of translating promising science into food on tables is never without its challenges. Listen in to this episode of Gastropod for the scoop on the history and potential impact of the Microbial Revolution.

Gastropod, a new podcast hosted by award-winning science journalist Cynthia Graber and Edible Geography-author Nicola Twilley.