Holly Tucker's Blog, page 45

November 6, 2014

Rasterschlüssel 44: The Stencil on Steroids

By Justin Yeh (Guest Contributor from Vanderbilt University)

An Allied cryptanalyst intercepts the message, “JDNTOENVIPDJ,” during World War II and attempts to decrypt it. He assumes it was encrypted using the German Enigma machine and performs the standard cryptanalysis, resulting in the message “PQNXLATIDNW.” He is completely baffled…the Allies had already broken the Enigma, so why was this message indecipherable?

An Allied cryptanalyst intercepts the message, “JDNTOENVIPDJ,” during World War II and attempts to decrypt it. He assumes it was encrypted using the German Enigma machine and performs the standard cryptanalysis, resulting in the message “PQNXLATIDNW.” He is completely baffled…the Allies had already broken the Enigma, so why was this message indecipherable?

The Germans had invented a new cryptographic weapon.

The Germans’ new cipher, the Rasterschlüssel 44, was introduced in 1944. Ironically, the origins of this new German cipher can be traced to British cryptography (Rijmenants). The cipher was used in the field, mainly by police forces and the army (Cowan 2004) instead of by diplomatic officials. The Rasterschlüssel 44 (RS 44) was a hand cipher, meaning that it could be implemented with pencil and paper, unlike the German Enigma, which required a machine to encipher and decipher a message. Like all hand ciphers, the RS 44 needed to balance security strength and convenience. The cipher had to be complicated enough to withstand decryption efforts, but not so complicated as to be difficult to use.

Even though the RS 44 is a relatively unknown cipher, it still played a substantial role in WWII. The Allies had already broken the Germans’ previous field cipher, the Double Playfair cipher, and all of the messages enciphered with the Double Playfair were being read (CryptoDen). The RS 44 allowed the German military and field troops to communicate securely without fear of revealing critical military strategies to the Allies. Had the RS 44 failed to secure German communications, the Allies would have gained a tremendous tactical advantage. Cowan (2004) lists translated messages sent on February 3rd, 1945 that were enciphered with the RS 44:

“An additional 16 cubic metres Otto fuel have been allocated from Muerlenbach delivery #IS20 to enable 3rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment to be brought up more rapidly.”

“Combat elements of II Battalion have set-off on foot. I Battalion will leave tonight by truck.”

The Allies were too slow in decrypting these messages to be able to react to this information, but these messages provide examples of the subject matter and importance of the content enciphered using the RS 44.

Mechanics

The method by which the RS 44 encrypts a message can be seen in the cipher’s name; “Rasterschlüssel” means “grid key” in German. The basic principle of the RS 44 is that the plaintext (the message being enciphered) is horizontally written into a grid, and then the ciphertext (the scrambled message) is obtained by vertically reading the columns from top to bottom and writing out the letters. This method of scrambling letters is called columnar transposition.

Here is an example:

“plaintext message”

Resulting ciphertext: ptee les axs ita nmg

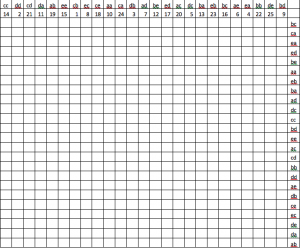

The grid scrambles up the letters so that the message can no longer be read. The RS 44 takes a basic grid and adds in a few tricks. First, the RS 44 uses a much larger 25×24 grid. The 25 columns are labeled with the numbers 1-25 in a random order. Each column is also randomly labeled with one of the 25 following pairs of letters:

aa ba ca da ea

ab bb cb db eb

ac bc cc dc ec

ad bd cd dd de

ae be ce de ee

Each of the 24 rows is also labeled with one of the 25 pairs (one pair is unused).

So a possible grid might look like this:

(Click on the image to see a larger version.)

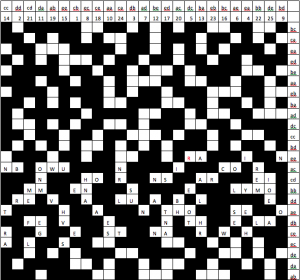

The rows and columns are labeled as previously specified, but the grid is not complete. In each row, 15 of the cells are randomly blacked out, leaving only 10 white spaces in each row. Here is an example:

The grid pictured above resembles a crossword puzzle gone horribly wrong, but it is actually a finished stencil for the RS 44. Now that the grid is complete, the plaintext message can be inserted into the stencil. In our example, the plaintext message will be:

“Rainbow unicorn horns are immensely more valuable than those of even the largest narwhals.”

A hypothetical German cryptographer encrypting this important, nonsensical wartime message would begin by choosing any white cell in the grid. In this example, let’s say he chooses the cell in column “dc” and row “ee.” He would then write the message horizontally, putting one letter in each blank space and continuing to the next row when he reaches the end of one row. Once he finishes, the grid would look like this:

Now that the letters are inserted into the rows, the cryptographer obtains the ciphertext by reading down the columns, similar to the example with the “plaintext message” in the first figure above. However, instead of starting with the leftmost column and reading to the rightmost column, the RS 44 uses the numbered columns to determine the order in which the columns are read.

The cryptographer will choose a column based on the time the message is written and the length of the message: in this example, the column is “ec,” also numbered “8”. This column only contains the letters: “h,” “n,” and “a,” so those are the first three letters of the ciphertext. The next column is “bd,” which is labeled “9.” The remaining ciphertext is obtained by reading the columns from top to bottom in increasing numerical order. After all the columns are read, the ciphertext message reads:

“HNANOESONMEGNANAALHRNTRAUHVSCWSTNAOAWVIBHMEFLREMLRNRLTIOEAEEBRSUIYEHREOTOLSEN”

However, our cryptographer is not finished. In order to indicate the cell in which he started writing his plaintext, he uses a 5×5 matrix of letters. The coordinates of the starting cell can be written as “dcee,” and he substitutes letters from the matrix, resulting in the letters “rvhp.” This substitution must be attached to the beginning of the message before it can be sent. In addition, the time that the message was written (16:21) and the message length (76) must also be included. This extra information is written as 1621-76-rvhp.

Finally, the message is ready to be sent:

1621-76-rvhp HNANOESONMEGNANAALHRNTRAUHVSCWSTNAOAWVIBHMEFLREMLRN RLTIOEAEEBRSUIYEHREOTOLSEN

Breaking the RS 44

The strength of the RS 44 lies in the randomness of the stencil. Accounting for repeat configurations and configurations that would not scramble the message, the number of stencil possibilities is still 2.06×10185 (Rijmenants). An Allied cryptanalyst that knew the dimensions of the stencil faced the impossibility of actually guessing the configuration of the stencil.

Despite the astronomical number of stencil possibilities, the RS 44 is not infallible. The number of possible stencils only protects the cipher from random guessing. However, the Allied cryptanalysts used other methods to break the cipher. They used captured stencils to decipher messages, but they had actually cracked the RS 44 without using a stencil. The enciphering technique of the RS 44 was secure; however, the Allies exploited the cipher’s improper implementation. Cryptographers using the stencil were prone to many mistakes, which required some messages to be sent more than once. The Allies used these similar messages to determine the plaintext and derive the stencil. Despite being broken, the RS 44 was still a relative success. The strength of the RS 44 was not that it was unbreakable, but that it was unbreakable in a short time frame. By the time the Allies had decrypted a message enciphered with the RS 44, the message was no longer relevant. Unlike Enigma, which was meant to be unbreakable, the RS 44 only had to be unbreakable for a given period of time. The fastest decryption of the RS 44 by the Allied cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park was ten days, but most messages took longer (Cowan 2004).

Weaknesses of the RS 44

As mentioned earlier, the cryptographers who enciphered messages with the RS 44 made many mistakes. This was due to the difficulty of using the stencil. Cryptographers placed tracing paper on the stencil and wrote on the tracing paper. Errors in counting occurred and the cipher was almost impossible to use in wet conditions (Cowan 2004). The mistakes in enciphering resulted in the decipherment of gibberish, which required a second message to fix the mistake. The resending of faulty messages greatly aided the Allies and their decryption efforts. The rules for enciphering a message were given in a 20-page instruction manual, but some cryptographers were still confused about the process (CryptoDen).

Another weakness of the RS 44 was the manufacture of the stencils. The pattern of the blacked out cells in each row was constructed using a rod. The Germans initially only had 36 rods to choose from, which meant that the millions of possible arrangements of black cells in each row was reduced to 36. If the Germans used a greater variety of rods, and therefore a greater variety of stencils, then the RS 44 would have been more secure. A wartime shortage of materials prevented the mass manufacture of different rods and stencils. In addition, the stencil used for enciphering messages had to be replaced daily. To produce a month’s supply of stencils, a book of 31 stencils had to be assembled and distributed to every unit that communicated using the RS 44. The strain on German supplies was significant; the RS 44, with its stencils and tracing paper, required 30 tons of paper per month (Cowan 2004).

Final Thoughts

Overall, the RS 44 succeeded in securing German messages. The Allied forces did manage to break the cipher and discover the mechanics, but not in a reasonable time frame. The RS 44 stencil provided a sufficient variability and number of possibilities to maintain the security of the message. However, difficulties in its application ultimately led to its decryption, and limited supplies inhibited its effectiveness. The true value of the RS 44 lies in the fact that scrambling a message using a grid with a few added layers of complexity can stump cryptanalysts but does not even require advanced technology, just paper and a pencil.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University. This post was originally published inFebruary 2013. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. The essays are shared here, in part, to give the students an authentic and specific audience for their writing. For more information on this cryptography seminar, see the course blog.

If you enjoyed this piece please come back the week of November 17th-21st for our week devoted to Cryptography!

Works Cited

Cowen, M. J. (2004). Rasterschlüssel 44 – the epitome of hand field ciphers. Cryptologia, 22(4), 115-148.

CryptoDen. (n.d.). Rasterschluessel 44 (RS 44): Introduction. Retrieved from http://www.cryptoden.com/index.php/21...

Rijmenants, D. (n.d.). Rasterschlüssel 44. Retrieved from http://users.telenet.be/d.rijmenants/...

Image: “Goal setting,” Justin See, Flickr (CC)

November 4, 2014

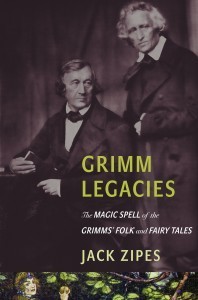

The Golden Casket: The Global Impact of the Grimm Legacies

By Jack Zipes (Guest Contributor)

From the beginning of their work as folklorists Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were very much aware of the never-ending process of storytelling and collecting folk tales. They knew there was a rich abundance of stories which they had yet to discover and which other people should also seek. Throughout their lives, the Grimms had encouraged friends, colleagues, and strangers to gather and share tales that emanated from an oral tradition.

The Golden Casket

By the time that they stopped collecting tales, they had fully realized the profound and prophetic quality of their simple last tale about a mysterious golden casket. In fact, they had opened the golden casket so wide that thousands if not hundreds of thousands of wonderful folk tales came pouring out into books throughout Europe and have kept coming. They had looked and found the right key that has opened up a worldwide cultural legacy that is unfathomable.

In the centuries before the Grimms produced the Kinder-und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales) the literate people of Europe had generally ignored or looked down upon the stories of the common people. Ironically, these were the tales with which they had also been raised. It was not until the end of the eighteenth century and beginning of the nineteenth century when nation-states were being formed that their attitudes toward history and national identity changed and led to a “romantic” rediscovery of fairy tales and other short genres such as animal stories, legends, humorous anecdotes, witch and ghost stories, and so on.

Setting the Standard in Folklore

The Grimms were not the first scholars to turn their attention to folk tales which they considered gems of German culture, relics that needed preservation. But they played a significant part in a widespread cultural trend and set high standards for collecting folk tales that marked the work of most European and American folklorists up through the twentieth-first century.

In fact, their long-term, scholarly investigation of narratives from all parts of Europe was a direct or indirect inspiration for philologists, collectors, writers, and translators of tales. As a result of the Grimms’ prodigious and timely influence, scholars in one country after another utilized folklore as a vehicle to promote a national language, literature, history, and mythology. The result is that the Grimms have left many legacies behind them not just one.

From the nineteenth century to the present the Grimms came to play a pivotal and unusual role in the evolution of western folklore and in the history of the most significant cultural genre in the world, the fairy tale. In the end, what the Grimms sought to bestow upon the German people has now become a global heritage.

Jack Zipes is professor emeritus of German at the University of Minnesota. In addition to his scholarly work on folk and fairy tales, he is an active storyteller in public schools. Some of his more recent publications include: The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films (2010), The Irresistible Fairy Tale (2012), and The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales (2013). He has just published Grimm Legacies (2014) which covers topics such as the transformation of the Grimms’ tales into children’s literature, the Americanization of the tales, the Grimmness of contemporary fairy tales, and the utopian impulse of fairy tales.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Grimm Legacies for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00 pm EST on November 30th to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that at this time we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms’ Folk and Fairy Tales”

Sigrid MacRae, “A World Elsewhere: An American Woman in Wartime Germany”

Jerry Brotton, “Great Maps”

November 3, 2014

The God of Fear versus Amazons and Persians

Phobus mosaic

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

In Greek myth, the capture of the Amazon Antiope by the Athenian king Theseus ignited the great war between Athens and the Amazons. Enraged by the hostile aggression of the Greek heroes led by Heracles and Theseus, in which the Amazon queen Hippolyte was killed for her war belt, the fierce warrior women of Pontus vowed revenge. They amassed a huge army and invaded Greece, breaking through the city walls and threatening to destroy Athens.

Seizing the high ground, the Amazons occupy the craggy Hill of Ares, pitching their tents in sight of the sacred Acropolis. All seems lost for the Athenians. But Theseus rallies his forces who take up positions in the battle to save Athens.

The fierce Amazon warriors own the upper hand. For seven days there is a stand-off. Tensions are high; the beleaguered Athenians are trembling before the grave danger they face.

In this crisis, Theseus consults an oracle. The oracle advises a sacrifice to Phobus. This advice underscores the Athenians’ desperate situation. Phobus is the god of fear and military rout, the personification of the terror of war. Our word “phobia” derives from his name.

The Sacrifice to Fear

We have a vivid picture of how the Sacrifice to Fear was carried out, thanks to a scene from the ancient tragedy Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus.

Soldiers carry out a large black shield and set it on the grass like a huge dish. A black bull is led to the spot and its neck held over the bowl of the shield. Cutting its throat, Theseus plunges his hands into the gore pouring into the shield. He calls out to Phobus, beseeching the god to lift the paralysis that grips the Athenian soldiers. Theseus begs Phobus to sow panic and terror among the Amazon warriors instead.

The next morning, confident that Phobus is on their side, Theseus orders the first assault on the Amazon strongholds. The bloody war lasts four months, but ends with the Athenian victory–Athens’ finest hour in the city’s mythic past.

The next time the Greeks sacrificed to Phobus, God of Fear, it occurred in a historical battle. As in the mythic Battle for Athens, the outnumbered Greeks were pitted against a powerful barbarian army of the East. The year was 331 BC, when Alexander the Great’s army faced Darius’s imposing Persian forces at Gaugamela. On the eve of that battle, Alexander sacrificed to Phobus, praying for the god to help him rout the Persians. Against all odds, Alexander was victorious and King Darius fled in terror from the battlefield.

A Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University, Adrienne Mayor is the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World” (2014).

November 2, 2014

How I Write…with Sarah Werner

An Interview with Sarah Werner (Guest Contributor)

An Interview with Sarah Werner (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: At what age did you really become interested in history? At what point did you begin writing about it?

Sarah Werner: It’s funny—up until recently, I never really categorized what I was interested in as history. But a lot of the literature I loved was from the past. It was reading Paradise Lost as a first-year college student that started me on the path to being an early modernist, and when I lived in London as a graduate student, it was devouring Victorian novels that helped me make sense of the city. It’s a little odd, I suppose, that my interest in the historical London led me to reading novels rather than any of the histories written about the city. But for me, Mrs Gaskell’s accounts of the tensions between northern and southern England is more engaging and gives me a view into the shifting identities of the nineteenth century than reading straight history would. All this shows why I got my PhD in English, not history!

Similarly, I never really thought about what I write as being about history up until very recently. In 2009, I had the delightful honor of being awarded the (now defunct) Cliopatria prize for best new history blog. But even as I was delighted, I was taken aback by the idea that what I was writing qualified for a history award. I was writing about books, not history! Even now, while I do identify with being a book historian, somehow I think of that as being different from being a historian. It’s not a disdain of history of my part that stops me from identifying more fully as a historian, but a respect for the discipline. Thinking as a historian is different than thinking as a literature scholar, it seems to me. The question of whether someone who is not a historian can write about history is, of course, a different matter: history is not the purview solely of historians, although anyone who writes about the past would be well served by reading up on the work of historians as they do so!

W&M: When it comes to your own writing projects, what are the benefits and challenges of working at the Folger?

Sarah Werner: There are so many benefits to being a staff member at the Folger for the sort of work I’m interested in. If I’m confused about the varieties and uses of 17th-century almanacs, I can call up examples from the vaults and look at them myself. Not sure about how the mise-en-page of incunable bibles might have reflected and shaped reading practices? Take a look at a few! And there’s the huge range of my colleagues’ expertise that I can draw from. If I’ve a question about the paper used in manuscripts, I can pop down and ask Heather Wolfe, the Curator of Manuscripts. If I’m not sure how to describe a physical characteristic in a book I’m looking at, there’s a whole room of catalogers I can chat with.

The challenge is that most of my work takes the form of administrative projects, and so there’s not nearly enough time to be able to go into the reading rooms and work with rare materials. Unlike for many standing faculty, being an active scholar is not part of my job description, and while there is certainly no stigma to pursuing research projects, there’s also only limited support for such work. It’s something I do in addition to my job, not as part of my job, but research is something I was trained to think of as part of my life. And so it can be frustrating when I see friends and colleagues in the Library on fellowships and sabbaticals and to know that I don’t have access to the same research funds and leave. The Folger does provide for the possibility of 3-month sabbaticals every 4 years and up to 4 weeks of annual research leave, and that’s certainly more than many other libraries allow. But both of my jobs at the Library have been one-woman shows, and there’s not funds provided for leave replacements—if I want to take a sabbatical, everything I’m responsible for grinds to a halt, and it’s not always easy to work out how to make that possible. Still, it’s a lot easier for me to sneak in small chunks of time than it can be for folks who do not work on the premises of a special collection and there are many, many jobs out there that do not include active research as part of their descriptions.

W&M: Can you tell us a bit about your writing space or your writing process? (i.e. what are the necessary components of a successful writing or research day)

Sarah Werner: A successful writing day for me is when I discover something that I really need to say. I don’t necessarily need to finish saying it that day—just the discovery of the motivation and the start of fleshing it out can be enough. I’ve not worked out what the difference is that makes me think “I need to tell someone this” rather than the less inspiring “This is interesting.” The former gets me writing, the latter makes me tuck the idea away. Sometimes ideas I tuck away come back and turn into impetus; if it’s something for The Collation or for my handbook, I’ll often note the idea (I find Workflowy perfect for this) in the hopes that it’ll eventually turn into something. The prompt of finding something cool and wanting to share it is a typical impetus for me, although sometimes I get a bee in my bonnet about something and that’s what drives me.

Sarah’s Writing Space

Writing space certainly matters. I can write in my office at the Folger, but not well—it’s slow and there are too many distractions. My desk at home is more my style. There I’m surrounded by books and objects I love and that helps give me the confidence to write. I keep my childhood books on a shelf in front of me, as well as a collection of old cameras that used to be my father’s, my youngest child’s former favorite stuffed animal, loads of photos, and a growing collection of books that are interesting physical objects. All of that lifts me up. And since writing does not always come easily, that buoying of spirits really helps!

W&M: What is the most unexpected thing you’ve learned as a writer? (about yourself, about writing and research, or even just a cool find from the archives).

Sarah Werner:Most of the writing I do these days is blogging—and the best thing about that is that it’s let me rediscover how much I love writing. When I was growing up, I was scribbling all the time: poetry, my journals, letters. And then the more academic writing I started to do, the less I connected with it. I took a lot of satisfaction from it, but it didn’t experience it as joyfully as I used to. And now, with blogging, I’ve remembered that writing can be fun. I’m hoping that some of that fun can rub off on the non-blogging writing projects I have in front of me. I think it will!

Sarah Werner is Digital Media Strategist at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Most of her history writing can be found either on her personal blog, Wynken de Worde (http://sarahwerner.net/blog), or on the blog she founded and runs for the Folger, The Collation (http://collation.folger.edu). She is also the author of Shakespeare and Feminist Performance and is currently writing a handbook on early modern printing practices.

October 30, 2014

A Queen’s Anger

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (Guest Contributor)

In the summer  of 1474 (only a few months after the acclamation ceremony I described in my earlier post), King Fernando met with miserable failure on the battlefield. Upon returning to the court, according to the chronicler Juan de Flores, his wife, Queen Isabel, delivered a scathing harangue: “Using the courageous words of a man rather than those of a fearful woman,” she upbraided Fernando. She said that as news reached her of the outcome she “had sat in the palace, with an angry heart, gritted teeth and clenched fists.” She berated his temerity and weakness.*

of 1474 (only a few months after the acclamation ceremony I described in my earlier post), King Fernando met with miserable failure on the battlefield. Upon returning to the court, according to the chronicler Juan de Flores, his wife, Queen Isabel, delivered a scathing harangue: “Using the courageous words of a man rather than those of a fearful woman,” she upbraided Fernando. She said that as news reached her of the outcome she “had sat in the palace, with an angry heart, gritted teeth and clenched fists.” She berated his temerity and weakness.*

Despite the fact that there are at least five contemporary chronicles of the monarchs’ reign, this account of the queen’s anger only appears in the one by Juan de Flores. Only one other comments on Isabel’s emotional state, saying simply that she was saddened by the loss.

We should ask ourselves, then, what image of the queen does Flores’ account create? At first blush we might think that he is criticizing her. What right did she have to speak to her husband like that? Conduct manuals of the day cautioned wives—even powerful ones—to be silent, circumspect, and obedient. Curiously, Flores may thwart this dilemma by endowing her with manly attributes. And he doesn’t limit himself to descriptions of Isabel. In fact, this assertive Isabel is consistent with his portrait of another forthright personality of Isabel’s day, Beatriz de Bobadilla. Beatriz, due to her husband’s illness, had periodically administered the city of Segovia. According to Flores, she performed the necessary tasks “like a very discrete man and woman” and with a “shrewdness more intense than women customarily possess.” Like Isabel, Beatriz conducts herself in a masculine fashion.

Flores’ contemporaries would have seen in his portrayals of Isabel and Beatriz familiar images of what they called a mujer varonil or manly woman. It was also how a fifteenth-century Spanish biography described the cross-dressing warrior Joan of Arc. This gender-bending category praised women not for feminine virtue, but for the transcendence of their womanly nature (perceived as weak) and the assumption of male qualities. Thus, Isabel’s anger is not a liability, but rather an indication of her strength.

* All translations are my own taken from Flores’ Crónica incompleta de los Reyes Católicos.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in Europe between 1400 and 1700 with an emphasis on Spain, queens, and convents.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 27 October 2011.

October 28, 2014

The Blue Books: Guides to the New Orleans Red Light District

By Gary Krist (Guest Contributor)

By Gary Krist (Guest Contributor)

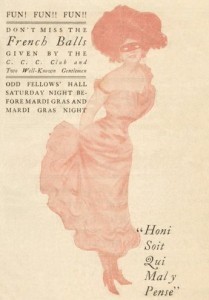

Reformers aren’t typically in the business of abetting prostitution. But when the reform-minded aldermen of New Orleans voted in 1897 to create a legally tolerated red-light district in the city, their intentions were impeccably upright. They recognized that any attempt to abolish prostitution entirely would be doomed to failure (at least in a worldly place like the Crescent City), and hoped instead to restrict the trade to a single neighborhood. Sidney Story, the alderman who wrote the relevant ordinance, designated an 18-block area located just behind the French Quarter and stipulated that prostitution would be illegal everywhere in the city except in this one neighborhood. The idea was to tuck vice and depravity away in a part of town where few “respectable” people would have to come into contact with it.

Guides to the Shopping Mall of Sin

So much for good intentions: The city’s new creation—which eventually came to be known as “Storyville,” much to the alderman’s annoyance—proved to be anything but low-profile. In fact, Storyville was soon elevating the oldest profession to new heights of visibility in the city. Within a few years of its creation, the restricted district had become world-famous as a virtual shopping mall of sin, offering debaucheries for every taste. And this shopping mall came with its own directory—the so-called Blue Books, which became the essential guidebooks for anyone hoping to visit the infamous neighborhood.

Published in numerous editions from 1900 to 1915, the Blue Books typically contained an alphabetical listing of the district’s better class of prostitutes (the “Tenderloin 400,” as one edition playfully called them). Each practitioner was conveniently identified by “race”—w for white, c for colored, J for Jewish, and oct. for octoroon—while the names of brothel madams appeared in boldface or all caps. Some editions also included pictures and descriptions of the major brothels, along with advertisements for whisky, beer, cigars, “cures” for venereal disease, restaurants, drugstores, lawyers, and, once, even a piano tuner.

The Sporting Man’s Savvy Local Friend

The Blue Books (which were sometimes red or green, since “blue” described the books’ racy contents, not their physical color) were distributed at train stations, barbershops, bars, restaurants, and by newsboys on street corners. Aimed principally at male tourists, they styled themselves as the itinerant Sporting Man’s savvy local friend: “Go through this little book,” the preface to one edition stated, “and when you go on a ‘lark’ you will know the best places to spend time and money…secure from hold-ups, brace games, or other illegal practices usually worked on the unwise in Red Light districts.”

The closing of the Storyville district in 1917 meant the end of open advertisement of prostitution in New Orleans. The last edition of the Blue Books was published in 1915. And although thousands of copies had been printed over the years, today the guides are very rare collector’s items, sometimes fetching thousands of dollars when sold at auction—a small price to pay, apparently, for a Baedeker to a colorful world long-gone.

Sources:

Arceneaux, Pamela D. “Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville.” Louisiana History 28, Fall 1987.

Landau, Emily Epstein. Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013

Long, Alecia P. The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865-1920. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004

Rose, Al. Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District. University of Alabama Press, 1974; Paperback edition, 1979.

Gary Krist is the bestselling author of City of Scoundrels and The White Cascade, as well as several works of fiction. His new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, has just been published.

Gary Krist is the bestselling author of City of Scoundrels and The White Cascade, as well as several works of fiction. His new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, has just been published.

W&M is excited to have five (5) copies of Gary Krist’s’s new book Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”

October 27, 2014

Traveling The Silk Roads

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

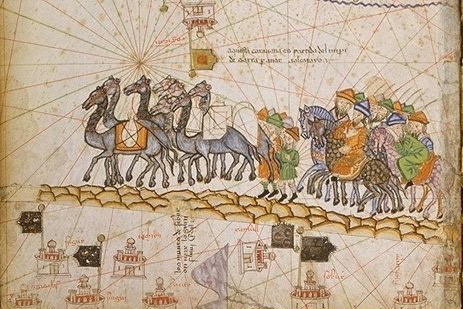

Caravan on the Silk Road 1380

We tend to use the phrase “the Silk Road” as if it were the Route 66 of East-West commerce. In fact, it is a metaphor. German geographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen (1833-1905) invented the name in the late nineteenth century, long after the overland luxury routes between Asia and the West had been supplanted by the sea trade. Instead of a single “Silk Road”, trade between China and the West traveled over a network of hazardous routes that led from China across Central Asia and then over the Iranian plateau to Baghdad and Damascus, or through the Syrian desert to the Mediterranean. The routes shifted as empires and markets rose and fell or stretches were rendered unsafe by armed nomads, bandits, war, disease, or tax collectors.

Ancient Roads

The Chinese had produced silk for several thousand years and traded with Central Asia for about a century when Rome discovered silk and what we think of as the Silk Road began. Rome first encountered silk in 53 BC in a battle with the Parthians outside of Carrhae. According to Plutarch, the Romans were blinded when the Parthians unfurled their embroidered banners, “shining with gold and silk.” Within sixty years of the defeat at Carrhae, the Roman Senate passed sumptuary laws forbidding men to wear silk. Roman critics grumbled about the effects of silk on Rome’s morals–and its trade balance. Romans paid for unwoven Chinese silk in gold, weight for weight; Pliny the Elder estimated that Rome lost 45 million sesterces a year to the silk trade. (To put this in context, a loaf of bread cost about half a sesterce. Forty-five million is a lot of sandwiches.)

Goods traveled all the way from Asia to Europe and from Europe to Asia; traders did not. First the Parthians, then the Sassanians and finally the Islamic kingdoms of Central Asia, blocked direct trade between China and the West–something that both the Chinese and the Romans complained about bitterly. The wealth of the silk trade created thriving cities and prosperous kingdoms throughout Central Asia. Well aware of the importance of the merchant caravans, Central Asian rulers built networks of caravansaries along the roads that linked the major cities: fortified inns that offered secure accommodations for merchant caravans that might include as many as 1,000 camels.

Under the Mongols

In the thirteenth century, the major routes of the East-West trade came under the control of the Mongols. Markets and producers that had been separated by hostile powers since the fall of Alexander the Great’s short-lived empire were once again linked under a single government. The Mongols boasted that a young woman could walk from one end of the empire to the other carrying a pot of gold on her head without being molested.* For the first time, merchants like Marco Polo were able to travel the entire length of the trading routes from Europe to China and back, though not many did.

The death of the Mongol ruler Timur** in 1405 was the beginning of the end of the Silk Roads. His successors were not able to hold together the vast Mongol empire. The Khanates disintegrated into a handful of warring Central Asian states, unable to control or protect the East-West trade.

China, too, was in a period of upheaval. The death of the last Mongol ruler of China is 1386 was followed by the rise of an ethnically Chinese ruling dynasty for the first time in centuries. The Ming rulers wanted to cleanse China of the corruption of foreign rule and restore traditional Chinese values.*** In 1426, the Ming Emperor Yongle closed China’s borders to the northwest.

The End of the Line

China’s borders were closed, but caravans continued to travel west for another hundred years. The Silk Roads met their end when European discoveries in navigation and shipbuilding opened up the sea route to India. The sea route was faster and less expensive. The caravans that traveled the Silk Roads were no longer needed to bring silk and spices from the East to the markets of Europe. Slowly the Silk Roads withered until only the romance remained.

* I have my doubts.

**You may know him as Tamurlane, the Anglicized version of a jeering nickname given him by his enemies– Timur-i-lang, Timur the Lame.

*** [political rant redacted]

October 22, 2014

Girl Warrior Fantasies, c. 1700

By Christine A. Jones (Regular Contributor)

Chic girl pirate Anne Bonny

Fairy tales are how we imagine the unimaginable. Beans can be magic and grow to the heavens. Frightening beasts turn out to be great princes in disguise. And girls are saved from annoying home lives by fairies and talking animals. Crazy things can happen.

Fairy-tale history contains some really juicy stuff, not all of which made it into the Mother Goose canon. For instance, how about a girl who shows up at court dressed as a knight and becomes the queen’s lover? Crazy indeed! Well, during the 1690s three French women authors thought up an ingenious plot for fairy tales where girls did their fighting for themselves. They showed up at court dressed as soldiers and did battle for the king. In each case, in fact, they became the kingdom’s best warriors. They were valiant, but also gentle and kind, and knew how to fold laundry. A rare combination, to be sure. And in the longest and most famous of these stories, by Marie Chatherine d’Aulnoy, the cross-dressed heroine has to fend off the queen’s advances with all her might.

Okay, the girl warrior and the queen never become lovers, but the love triangle among the queen (who loves the knight), the knight (who loves the king), and the king (who loves the knight but cannot figure out why) makes up the entire plot of the story. Historically, there had been woman warriors in France by the seventeenth century, but none of them had had quite this much fun at court. Read d’Aulnoy’s story, “Belle-Belle or the Chevalier Fortunate”, in Jack Zipes, Beauties, Beasts and Enchantments: Classic French Fairy Tales (New York: New American Library, 1989).

Christine A. Jones is co-editing a fairy tale anthology and writing a book on early porcelain experiments in France. She is Associate Professor of French and Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at the University of Utah.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 12 December 2009.

October 21, 2014

Novels in Shorthand

By Jack El-Hai (Regular Contributor)

A century ago, hundreds of thousands of people around the world regularly used shorthand. Secretaries, stenographers, court reporters, journalists and others depended on the elaborate shorthand systems that Isaac Pitman and John Robert Gregg developed in the nineteenth century, and countless schools and publishers seized the business opportunity to train them. Talented practitioners could write at speeds up to 280 words per minute.

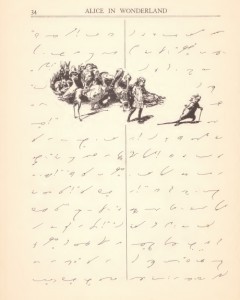

A page from the Gregg edition of Alice in Wonderland.

Two distinct skills comprised shorthand proficiency. One was the ability to quickly and accurately set down spoken words using the shorthand systems, and the other was mastery of the translation of passages of shorthand into standard written or spoken language. To teach the second skill, publishers produced printed shorthand texts that students could use to practice translation.

These texts grew increasingly complex, and apparently so did their uses. In 1903, the publishers of the Gregg method released the first novel entirely rendered in shorthand — an 87-page edition of Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son by George Horace Lorimer, a longtime editor of The Saturday Evening Post. Little read today, the novel unfolds in epistolary style, a comfortable format for students used to taking down correspondence. But few students would have required such a long exercise in translation, suggesting that some may have read this novel in shorthand for edification or pleasure (or to show off).

Ten years later, a couple of shorthand short stories, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” by Washington Irving and “The Great Stone Face” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, appeared in print. Then, starting around 1918, additional literary editions came out, including shorthand versions of Alice in Wonderland, The Sign of the Four, and such short stories as “The Diamond Necklace” by Guy de Maupassant, “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens, and “A Descent into the Maelström” by Edgar Allan Poe.

Because Gregg shorthand is a phonetic system in which the strokes represent sounds and don’t correspond with letters or words, consuming a novel from the squiggles and lines on the page must have offered a unique reading experience. The strokes for the word raise, for example, are the same as the strokes for raze.

New technologies of the past 75 years — dictation machines, audio recorders, and personal computers — have decimated the ranks of shorthand users, and the various systems might now qualify as endangered languages. (The Gregg system has not been updated since 1988.) In libraries and digitized collections, however, shorthand novels live on. Even though few people can now read them, these literary translations display a strange and persistent beauty.

Further reading:

Carroll, Lewis. Alice in Wonderland (Gregg shorthand edition). The Gregg Publishing Company, c. 1918.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Sign of the Four (Gregg shorthand edition). The Gregg Publishing Company, c. 1918.

Price, Leah. “Diary” [essay on the history of shorthand]. London Review of Books, December 4, 2008.

Lafayette the Centaur

By Laura Auricchio (Guest Contributor)

By Laura Auricchio (Guest Contributor)

The Marquis de Lafayette, French hero of the American Revolution, was a man of many names. In 1757, a rural curate honored a host of heavenly saints and earthly ancestors by baptizing him Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette. From the 1770s through the 1830s, grateful Americans came to know him as the Hero of Two Worlds, the Apostle of Liberty, or – in affectionate shorthand – simply The Marquis. During the French Revolution, though, less flattering nicknames accrued to Lafayette. Royalists denounced him as a traitor; radicals termed him a coward; and, in 1791, at least one caricaturist friendly to the monarchy depicted Lafayette as a centaur – a monstrous man-horse hybrid.

On one hand, the caricature mocks Lafayette’s uncommon attachment to his steed. From July 1789 to July 1791, Lafayette cut a conspicuously equestrian figure on the streets of Paris. As Commander of the National Guard, he was so often seen atop a majestic white horse that newspapers and gossip sheets described man and beast as inseparable. According to some reports, the two fused so thoroughly in the popular imagination that at one event in 1790s Lafayette’s admirers nearly smothered both man and mount with warm embraces.

But in eighteenth-century France, where every learned man knew his Greek mythology, picturing Lafayette as a centaur implied something darker. Centaurs were dangerous beings whose base and disorderly natures threatened the very foundations of civilization. So, the caricature implies, was Lafayette, seen here galloping past the severed heads of royalists.

Staunch monarchists held Lafayette responsible for the downfall of Louis XVI, but Lafayette, who wanted to reform, not abolish, the Bourbon throne, considered himself blameless. “The Blameless One” – Le Sans Tort – is the title of the caricature. It is no coincidence that, in French, “Le Sans Tort” sounds precisely like “the centaur.”

Laura Auricchio is Associate Professor of Art History and Dean of the School of Undergraduate Studies at The New School for Public Engagement. Her newest book The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered offers a visually-informed biography on the Marquis de Lafayette.

Laura Auricchio is Associate Professor of Art History and Dean of the School of Undergraduate Studies at The New School for Public Engagement. Her newest book The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered offers a visually-informed biography on the Marquis de Lafayette.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Laura Auricchio’s new book The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”