Holly Tucker's Blog, page 47

October 7, 2014

Sex vs. God: How America Got Its Name

By Michael Blanding (Guest Contributor)

By Michael Blanding (Guest Contributor)

Everyone knows that Columbus “discovered” the New World in the 15th century. So why is our continent named America instead of Columbia? It might have to do with a universal truth: sex sells better than God.

When Italian explorer Christopher Columbus first arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, he thought that he had landed on the Indie islands off the coast of Cathay, and it was only a matter of time before he’d find the gold mines and pleasure palaces of the Kublai Khan. As he island-hopped for the next few months, however, none of the native inhabitants of the island seemed to know what he was talking about. On subsequent voyages between 1493 and 1504, Columbus became more and more desperate, insisting not only that he had found Asia, but also more grandiosely claiming he’d discovered the mythical Garden of Eden. He even declared himself a harbinger of the Second Coming of Christ and the End of the World, circulating his ideas in a book called the Book of Prophecies.

Sex Sells: Vespucci’s Pamphlet on America

At the same time Columbus’ book was making the rounds of Europe, another very different pamphlet was also circulating. This one, written by Columbus’ fellow Italian Amerigo Vespucci also claimed to have discovered a passage to Asia during voyages between 1497 and 1504. However, it went further to describe new lands in the Southern Hemisphere that had never been described before. Vespucci was particularly explicit about the native inhabitants of these lands—especially the women, whom he said “go naked and are exceedingly lustful,” adding tantalizingly, “I have deemed it best (in the name of decency) to pass over in silence their many arts to gratify their insatiable lust.” Of course, that only led readers to speculate further, causing the pamphlet to be in hot demand across Europe (even though today scholars debate whether Vespucci ever even made the voyages he claimed). Columbus’ increasing delusions of grandeur, meanwhile, alienated him from his peers; he died obscure and impoverished in 1506.

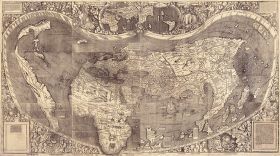

Thus, it makes sense that when German mapmaker Martin Waldseemüller produced the first map to show a separate continent in the Western hemisphere in 1507, he chose to name it after the person given credit for discovering it, feminizing Vespucci’s first name to call it “America.” As more doubts began to emerge about Vespucci’s story, Waldseemüller apparently thought better of the decision, taking the name off later maps, but by then it was too late. The name was adopted by other mapmakers including Gerard Mercator, who popularized it in his new Atlas—and the name America was forever cemented in history. So important was Waldseemüller’s map that centuries later the only remaining copy would become the most expensive map ever sold, bought by the U.S. Government for $10 million in 2003. It is now on permanent display at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., as the “birth certificate of America.”

Michael Blanding is the author of The Map Thief: The Gripping Story of an Esteemed Rare-Map Dealer Who Made Millions Stealing Priceless Maps (Gotham, 2014).

Michael Blanding is the author of The Map Thief: The Gripping Story of an Esteemed Rare-Map Dealer Who Made Millions Stealing Priceless Maps (Gotham, 2014).

October 6, 2014

A Young Lady’s Poem about the Queen of Amazons, 1680

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

The English poet Anne Killigrew died of smallpox, at age 25 in 1685. The poet John Dryden compared her to Sappho when her poetry was published after her death. Well educated in Greek myth and history, Anne was encouraged by a circle of intellectual early feminist writers who urged women to rebel against male domination.

Anne’s first poem, “Alexandreis,” was an ode to the meeting of Alexander the Great and an Amazon queen in 330 BC, an incident reported by the historians of Alexander’s campaigns. After a verse praising the young world conqueror (and two more declaring the modesty of her talents and calling on ancient Muses to aid her), the poem finally takes off with an arresting scene.

The sun rises in azure skies over the exotic Hyrcanian desert and suddenly illuminates a formidable army, a mirage of bright silver armor and scarlet plumes. Anne describes their splendid appearance: With crescent shields and panther-skin capes slung over their shoulders, bows and quivers “rattled by their sides” and each warrior carried a “well try’d Speare.”

Only then do we discover that these impressive soldiers are not men but women! –“Warlike Virgins” from the mythic Amazon homeland. The host is led by Thalestris, a formidable ruler seeking glory like her ancestor Penthesilea, the Amazon who came to the aid of Troy in the Trojan War. Alexander’s noble courage and magnificent triumphs fired Thalestris’s “soul,” filling her with longing to “see the Hero she so much admir’d.” She dispatches a messenger to Alexander’s camp.

Anne imagines their meeting, imbued with suspense. A “great cloud of Dust” and “Loud Neighings of Steeds and Trumpets” herald Alexander’s arrival at the head of his own splendiferous army of “Burnisht Gold.” The two troops, one silver and the other gold, come to a halt and face each other respectfully and expectantly. As they gaze in amazement at each other, a pregnant hush falls over the scene.

In the next verse, the “Heroick Queen” Thalestris advances boldly. “And thus she spake.”

But here Anne’s poem breaks off: A note explains: “This was the first Essay of this young Lady in Poetry, but finding the Task she had undertaken hard, she laid it by till Practice and more time should make her equal to so great a Work.”

The unfinished poem is an eloquent evocation of male and female equality. Why did Anne never complete the poem? We might venture a guess. Despite her sophisticated education, spelling out Thalestris’s scandalous mission might have been a challenge for a young lady in the court of James II. According to all the ancient historical accounts, the Amazon invited Alexander to have sex so that she could bear his child. Alexander agreed and devoted a fortnight to impregnating Thalestris.

Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University and the author of “The Poison King: Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award, and The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014).

October 3, 2014

The Pickelhoube: How a World War I Helmet Turned into Caricature

By Peter Doyle (Guest Contributor)

+ A Giveaway

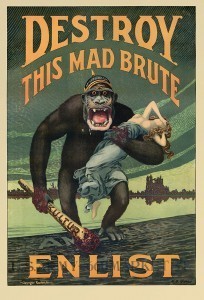

In 1914, all armies were equipped with some form of uniform cap or ceremonial helmet; but it is the German pickelhaube that is the pre-eminent example of the type: gaudy, impractical and affording little protection from either the elements or from shell fragments and bullets. This style of headdress was adopted in 1842, and with its long history, the pickelhaube became a prominent part of the military imagery of the Prussian state, and, later, of Germany itself. The image of the strong German soldier in a spiked helmet was a striking one; with military fashion following the victors spiked helmets emerged at the expense of French-style kepis in the late nineteenth century armies of many countries, the United States included.

In 1914, all armies were equipped with some form of uniform cap or ceremonial helmet; but it is the German pickelhaube that is the pre-eminent example of the type: gaudy, impractical and affording little protection from either the elements or from shell fragments and bullets. This style of headdress was adopted in 1842, and with its long history, the pickelhaube became a prominent part of the military imagery of the Prussian state, and, later, of Germany itself. The image of the strong German soldier in a spiked helmet was a striking one; with military fashion following the victors spiked helmets emerged at the expense of French-style kepis in the late nineteenth century armies of many countries, the United States included.

All-in-all, the helmet was expensive to make, complex and used many important war materials. In an army that grew rapidly, its production was unsustainable. Ersatz or replacement materials were quickly utilized: steel, felt even, to create the complex helmet shell. The example illustrated was introduced in June 1915. Gone were the shiny brass fittings, a metal much in demand to serve the munitions industry. In their place were oxidized steel fittings, cheaper to produce and less visible. The helmet spike was also removable.

Pickelhaubes helped define the image of the German soldier as an aggressor, particularly with its prominent spike. The alien appearance of the pickelhaube made it the target of Allied propaganda, and the helmet appeared in images intended to invoke national hatred. The spiked headgear was worn by snarling beasts, inhuman ravishers of women and despoilers of Europe’s cultural heritage: political cartoonists such as Louis Raemakers had a field-day with its ungainly image. It was destined to be replaced in 1916 by the Stahlhelm or steel helmet: and with it, fatalities from head wounds declined dramatically. With the passing of the pickelhaube came the birth of industrialized warfare; there was little room for the ceremonial in the killing fields of Flanders, Artois or the Argonne.

Pickelhaubes helped define the image of the German soldier as an aggressor, particularly with its prominent spike. The alien appearance of the pickelhaube made it the target of Allied propaganda, and the helmet appeared in images intended to invoke national hatred. The spiked headgear was worn by snarling beasts, inhuman ravishers of women and despoilers of Europe’s cultural heritage: political cartoonists such as Louis Raemakers had a field-day with its ungainly image. It was destined to be replaced in 1916 by the Stahlhelm or steel helmet: and with it, fatalities from head wounds declined dramatically. With the passing of the pickelhaube came the birth of industrialized warfare; there was little room for the ceremonial in the killing fields of Flanders, Artois or the Argonne.

Peter Doyle is a military historian and geologist, specializing in battlefield terrain, and the author of World War I in 100 Objects (Plume Books.) He has appeared on television as a contributor on television and in documentaries including WWI Tunnels of Death, The Big Dig, and Battlefield Detectives. He is currently Visiting Professor at University College London.

Peter Doyle is a military historian and geologist, specializing in battlefield terrain, and the author of World War I in 100 Objects (Plume Books.) He has appeared on television as a contributor on television and in documentaries including WWI Tunnels of Death, The Big Dig, and Battlefield Detectives. He is currently Visiting Professor at University College London.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Peter Doyle’s new book World War I in 100 Objects for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”

October 1, 2014

The Fairest Maiden of Them All: Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham

How Edward might have looked in disguise: a well dressed little girl (far right) in Hans Memling’s Donne triptych. (Image courtesy of Hans Memling’s website.)

By Susan Higginbotham (Guest Contributor)

“Edward? Good Lord, you did dress him as a girl!”

“Aye . . . He bore his womanhood like a man, you might say.”

Edward Stafford, the third Duke of Buckingham (1478-1521), is mainly known today for finding out the hard way that offending Henry VIII could cost someone his head. Less well known is the episode when the five-year-old Edward—dressed as a girl—was hidden from Richard III’s agents.

Edward’s adventures in cross-dressing began in October 1483 when Edward’s father, Henry Stafford, the second Duke of Buckingham, joined the ill-fated uprising against Richard III known as Buckingham’s rebellion. The enterprise proved fatal to Henry, who died on the scaffold at Salisbury. Before he was captured and executed, however, he had entrusted Edward to Richard Delabeare, who had close ties to the Stafford family. Richard Delabeare later married his servant Elizabeth Mors, whose recollection of this episode was found in the Stafford family papers.

With Henry dead, Richard III began searching for Edward, who proved to be elusive, thanks to Elizabeth. She shaved the lad’s forehead and dressed him in a “maiden’s raiment.” At one point when a search party arrived, Elizabeth fled to a park with Edward, sitting with her no doubt squirming charge for four hours until the danger was past. After that, Elizabeth took Edward to Hereford. Edward made the journey as would a young lady of quality: “rydinge behynde Willm ap Symon asyde upon a Pillowe like a gentelwoman ridde in gentelwomans apperell.” Rather sweetly, Elizabeth concluded her story, “And I wisse he was the fearest gentelwoman and the best that ever she hadd in her Daies.”

Nothing more is heard of Edward’s whereabouts during Richard III’s reign, but in Henry VIII’s reign, Edward was noted for his sartorial splendor, such as in 1513, when he appeared in an outfit “full of Spangles, and little Belles of golde, marueylous costly and pleasant to behold.” One wonders if on such occasions, the duke ever thought back to his long-ago disguise in 1483.

Susan Higginbotham’s new novel, The Stolen Crown , set during the Wars of the Roses, tells the story of Edward’s parents, Henry, Duke of Buckingham, and Katherine Woodville. Susan is working on a novel about Margaret of Anjou.

, set during the Wars of the Roses, tells the story of Edward’s parents, Henry, Duke of Buckingham, and Katherine Woodville. Susan is working on a novel about Margaret of Anjou.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 19 March 2010.

September 30, 2014

Those Saucy Grimms’ Fairy Tales That Your Mother Never Told You: The Original First Edition of 1812/15

By Jack Zipes (Guest Contributor)

By Jack Zipes (Guest Contributor)

+ A Giveaway

When Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published their famous Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales) in 1812, followed by a second companion volume in 1815, they had no idea that such stories as “Rapunzel,” “Hansel and Gretel,” and “Cinderella” would become the most celebrated in the world. Nor did they ever think that their collected tales would eventually be considered great children’s literature. Clearly, if they were living today, they would be shocked to discover how their tales have been misread and hyped and spread throughout the world in all sizes and shapes, not to mention in films and TV programs that might make them shudder.

Warning: Fairy Tales Not Meant for Children

Yet, despite their great fame, or perhaps because of their fame, few people today are actually familiar with the original tales of 1812/15. This is in part due to the fact that the Grimms published six other editions during their lifetime, each extensively revised and expanded in content and style, up until the final edition of 1857. From then on this so-called definitive edition has been translated into over 120 languages and often translated into English with illustrations geared to charm children.

Interestingly, the Grimms, who were great philologists, never intended their original edition to be read by children, for it contains scholarly prefaces and notes and blunt and bizarre tales such as “How Children Played at Slaughtering,” “Riffraff,” fabulous animal stories, farces, and fragments about toads and spiders. Moreover, the Grimms did not shy away from erotic and scatological tales or from depicting gruesome family conflicts. So, Rapunzel is impregnated by a prince, and Snow White’s mother wants to murder the innocent girl not her stepmother. Lovers betray one another. Animals are more humane than humans. Many of the tales were recorded in dialect. Most of them did not have fairies, and almost all of them can be traced to European, Middle Eastern, and Asian sources.

For the very first time, Princeton University Press will be publishing the first complete English translation, The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, this autumn. All 156 stories from the 1812/1815 edition will be made available in one beautiful book, accompanied by sumptuous illustrations by Andrea Dezsö. From strange tales such as “The Hand with the Knife,” “Herr Fix-It-Up” to “Princess Mouseskin” and “The Golden Key,” wondrous worlds unfold in this new collection — heroes and heroines are rewarded, weaker animals triumph over the strong, and simple bumpkins prove themselves not so simple after all. These unusual and startling tales resonate with diverse voices, rooted in oral traditions, that are absent from the Grimms’ later, more embellished editions of tales. While the tales in this first edition cannot be considered the “authentic” Grimms’ tales because they originated in different regions of Europe, they are beguiling because they enable us to see how the Brothers worked as scholars and storytellers, using their knowledge and imagination to transform and create striking narratives that have influenced millions of readers.

For the very first time, Princeton University Press will be publishing the first complete English translation, The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, this autumn. All 156 stories from the 1812/1815 edition will be made available in one beautiful book, accompanied by sumptuous illustrations by Andrea Dezsö. From strange tales such as “The Hand with the Knife,” “Herr Fix-It-Up” to “Princess Mouseskin” and “The Golden Key,” wondrous worlds unfold in this new collection — heroes and heroines are rewarded, weaker animals triumph over the strong, and simple bumpkins prove themselves not so simple after all. These unusual and startling tales resonate with diverse voices, rooted in oral traditions, that are absent from the Grimms’ later, more embellished editions of tales. While the tales in this first edition cannot be considered the “authentic” Grimms’ tales because they originated in different regions of Europe, they are beguiling because they enable us to see how the Brothers worked as scholars and storytellers, using their knowledge and imagination to transform and create striking narratives that have influenced millions of readers.

Jack Zipes is professor emeritus of German at the University of Minnesota. In addition to his scholarly work on folk and fairy tales, he is an active storyteller in public schools. Some of his more recent publications include: The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films (2010), The Irresistible Fairy Tale (2012), and The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales (2013). He has just published The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition (2014).

Jack Zipes is professor emeritus of German at the University of Minnesota. In addition to his scholarly work on folk and fairy tales, he is an active storyteller in public schools. Some of his more recent publications include: The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films (2010), The Irresistible Fairy Tale (2012), and The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales (2013). He has just published The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition (2014).

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Jack Zipes’s new book The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”

September 29, 2014

The Golden Spoon

By Gastropod

Chances are, you’ve spent more time thinking about the specs on your smartphone than about the gadgets that you use to put food in your mouth.

But the shape and material properties of forks, spoons, and knives turn out to matter—a lot. Changes in the design of cutlery have not only affected how and what we eat, but also what our food tastes like. There’s even evidence that the adoption of the table knife transformed the shape of European faces.

To explore the hidden history and emerging science of cutlery for our brand new podcast, Gastropod spoke to Bee Wilson, food historian and author of Consider the Fork, and Zoe Laughlin, co-founder of the Institute of Making at University College London. Below are some of our favorite stories from those conversations.

One of the earliest forks in Britain (made between 1587 and 1606), found by archaeologists excavating the site of the Elizabethan-era Rose Theater. Called a sucket fork, it was used for eating sweetmeats, such as dried and candied fruits. Later versions had a spoon at the other end, like a proto-spork.

The Evolution of the Fork

First, some history. Consider the Fork is one of our favorite food books: in it, Bee Wilson takes readers on a fascinating journey through the evolution of kitchen technology and its impact on our lives. It’s packed with astonishing details that gave us a whole new appreciation for humble appliances such as the can opener and the kitchen timer. Wilson ranges across human history, from the sixteenth-century adoption of the enclosed oven (before then, chefs often worked naked or just in underpants, to avoid catching their clothes on the open flames) to the 1994 “invention” of the Microplane grater, which took place when Canadian housewife Lorraine Lee borrowed a carpentry rasp from her husband’s hardware store to zest orange for a cake.

But it was the chapter on cutlery that really caught our attention. Although it’s hard to imagine life without them now, forks are a relatively recent addition to the table—and they weren’t a big hit at first. In the sixteenth century, as aristocratic Italians began to replace their single-pronged ravioli spears with a multi-tined fork, the rest of Europe still saw the fork as “this bizarre, weird, slightly fetishistic device,” Wilson explained. “Why would you want to put metal prongs into your mouth along with the food? It just didn’t seem like a natural way to eat.” Indeed, when a Englishman, Thomas Coryate, adopted the fork habit after traveling to Italy at the start of the seventeenth century, his friends—including the playwright Ben Jonson and the poet John Donne—teasingly called him “furcifer,” which meant “fork-holder” but also “rascal.”

[image error]

Pages from the 1910 Gorham Buttercup pattern silver catalog (left) and the 1898 Gorham Strasbourg pattern silver catalog (right), which together list more than 100 different items of cutlery, including the relish fork, asparagus fork, tomato serving fork, lemon fork, pickle fork, sardine fork, vegetable fork, and beef forks shown above. The full Buttercup pattern also included the infamous ice cream fork. Via Eden Sterling.

It wasn’t until a century later, in the early 1700s, that eating with a fork was accepted across Europe—in part, Wilson explains in the book, due to the transition from bowls and trenchers, whose curves were better suited to spoons, to flatter china plates. That was followed, another hundred years later, by an explosion in fork shapes and a corresponding wave of “fork anxiety.” As Wilson described it, the transition to serving meals in a succession of courses, each with a fresh set of cutlery, rather than just laying all the dishes on the table for diners to help themselves, led to the development of specialized “forks for olives, forks for ice-cream, forks for sardines, forks for terrapins, forks for salads”—even forks for soup, though that was rapidly condemned as “foolish,” and the soup spoon was restored.

The Search for the Golden Spoon

But, if forks have a complicated history, the future of spoons may well be golden. Literally. Zoe Laughlin, who confessed to being driven, in part, by a childhood obsession with finding the perfect spoon, has been conducting scientific research into the sensory properties of materials. Working out of the Institute of Making, a London-based cross-disciplinary research club, she started exploring the different tactile and aural sensations of metals. Next, she wondered how metals taste. Scientists had researched this question before, by having people swish metal salts around in their mouth. To Laughlin, that methodology made no sense. We put metal in our mouths every day, in the form of cutlery—why not just do a spoon taste test?

Before long, she had volunteers lining up to suck on a set of seven spoons that were identical in shape and size, but plated with different metals. Her results showed that different metals really do taste different—the atomic properties of each metal affects the way the spoon reacts with our saliva, and so, for instance, copper is more bitter than stainless steel.

From left to right: copper-, gold-, silver-, tin-, zinc-, chrome-, and stainless steel-plated spoons. Photograph by Zoe Laughlin.

Her next step was to figure out how the taste of different metals affects the flavor of food. Working with a top chef, she hosted a spoon-and-food pairing dinner party, in which food writers and scientists discovered the curious affinity of tin for lamb and pistachio. One spoon ruled them all, however: as Laughlin put it, “The gold spoon is just sort of divine. It tastes incredibly delicious and it makes everything you eat seem more delicious.” After tasting mango sorbet off a gold spoon, Laughlin told us, with a note of regret in her voice, “I thought, I can’t believe I’m ever going to eat off anything other than gold ever again. Sadly, of course, I do.”

Bee Wilson and Zoe Laughlin are guests on the first episode of Gastropod, the new podcast hosted by award-winning science journalist Cynthia Graber and Edible Geography author Nicola Twilley. Listen to the first episode, The Golden Spoon, for many more shocking cutlery revelations, and tune in every two weeks for a new

September 28, 2014

How I Write History…with David Laskin

[image error]An Interview with David Laskin (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: What role did history play in your relationship with your family?

David Laskin: Growing up, I always assumed history happened to other families not ours – families whose ancestors had fought at Gettysburg or had crossed the Atlantic in chains in the holds of slave ships. It wasn’t until I began researching The Family that I understood that history made and broke my family as well. I came to realize that my relatives, who had always struck me as tense people with accents who got together at holidays to eat too much and talk too loudly, embodied the three great currents of 20th century Jewish history: immigration to the US, the founding of the state of Israel, and the Holocaust.

W&M: What are some of the rewards and challenges of writing family history?

David Laskin: When you write family history, one fundamental question always gnaws away at the back of your mind: why would anyone care about my family? Making your own family story universal – and widely compelling – is the great challenge of this genre. This is also one of the great rewards since the deeper you delve into your ancestors’ stories, the more you see how historically significant their lives were. Ordinary people live and make history – our task as family historians is to connect the dots between their daily lives and the epoch-making events of the day. When we do our work well, we create the most accessible, compelling portals into the past

W&M: Can you tell us about your major resources and sources of information?

David Laskin: My primary resources for the narrative nonfiction books I write are family stories – either revealed to me in interviews or recounted in letters, diaries, journals, court records, police files, etc. In my previous two books The Children’s Blizzard and The Long Way Home, I had to make a big, time-consuming investment at the start in tracking down families who had lived through the historic events I was writing about (a killer winter storm in the former; the immigrant experience in the First World War in the latter). I advertised in local newspapers and solicited stories through the immigrant press. I delved into archives all over the country. I followed up promising leads from friends and acquaintances. But with The Family I had a big running start since my cast of characters (my mother’s family) was already in place. In fact, in the course of my research, I discovered many wonderful relatives I had never met before.

W&M: What is the most unexpected thing you’ve learned as a writer?

David Laskin: I know this sounds corny, but I wrote the final pages of The Family with tears in my eyes because I had come to feel so close to my ancestors. I am descended from a long line of scribes – back to my great-great-great grandfather and probably farther – and I came to realize that I am a kind of scribe as well, even though the texts that I write and redact are not sacred. This realization filled me with pride and wonder.

W&M: What is the most important piece of advice you have for researchers or new scholars beginning a new project?

David Laskin: The Internet is a fantastic resource and our work as historians is incomparably easier because of it – but your computer is only the beginning, not the end of historical research. There is a ton of fantastic material out there that has not yet been digitized, starting with the stories told around kitchen tables or whispered in cafes or the back of churches or synagogues. Wonderful as Google mapping has become, there is no substitute for walking the walk in the places you are writing about. Travel with your eyes and ears open, talk to as many people as you can, do your homework (along with your online surfing) – but then get out there and see and feel what you are writing about.

David Laskin writes suspense driven narrative nonfiction about the lives of ordinary people caught up in the crises of history. His recent titles include The Children’s Blizzard (Harper Perennial, an award-winning national bestseller), The Long Way Home: An American Journey from Ellis Island to the Great War (Harper Perennial, winner of the Washington State Book Award) and The Family: A Journey into the Heart of the 20th Century, just out in Penguin paperback.

David Laskin writes suspense driven narrative nonfiction about the lives of ordinary people caught up in the crises of history. His recent titles include The Children’s Blizzard (Harper Perennial, an award-winning national bestseller), The Long Way Home: An American Journey from Ellis Island to the Great War (Harper Perennial, winner of the Washington State Book Award) and The Family: A Journey into the Heart of the 20th Century, just out in Penguin paperback.

September 25, 2014

The History of Nail Polish

By Angus Trumble (Guest Contributor)

Brightly colored synthetic nail polish first crash-landed in the field of cosmetics in Paris in the 1920s, and for several decades encountered much resistance. The use of color at the fingertips was thought to conceal some sinister hint of racial impurity, or else to conceal the humble origins or grittily obscure shop-floor activities of certain female stars in the Hollywood constellation.

Pioneering advocates for African-American rights felt at first that colored women either didn’t need to use nail polish, or should avoid it on grounds of dignity. Psychiatrists attacked it as a form of self-mutilation; there were objections to color, to color and texture, to the risk to one’s health, even to the extravagant cost, which after all was not all that extravagant—hence its huge success as a global fad.

Twenty years ago the international cosmetics business was worth approximately $20 billion worldwide. Last year it was worth $250 billion. Nail polish and related products—which now include fake nails, ground coats, top coats, stenciled and other decorations, glitter, frosting, and so on—account for a significant proportion of that huge figure, while the constantly growing number of available brands, colors and textures employ ever more improbable names. “Innocent nude,” “I’m not really a waitress,” “Catherine the grape,” and “vixen” are by no means unusual, as any seasoned shopper will attest.

To some extent, through the twentieth century, nail polish went head-to-head with the declining glove trade, but not always. Rather like the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties in Britain just now, the two modes—brightly colored fingernails and a bewildering array of styles of glove—managed, via the fashion literature, very effectively to bolster each other, though it was gloves that eventually bit the dust.

I’m not sure that the new Prime Minister need worry too much about this; Queen Elizabeth II remains committed to the wearing of gloves.

Angus Trumble was born and raised in Melbourne, Australia, and is the youngest of four brothers. Formerly the Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, he is now Director of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in Canberra, Australia. He is the author of The Finger: A Handbook

Angus Trumble was born and raised in Melbourne, Australia, and is the youngest of four brothers. Formerly the Senior Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, he is now Director of the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in Canberra, Australia. He is the author of The Finger: A Handbook and Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century.

and Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 May 2010.

September 23, 2014

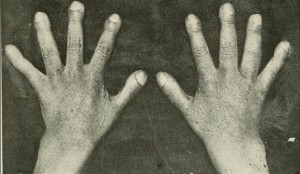

The Murderer’s Thumb: A Short History

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

A few years ago, my teenage daughter announced that she had a malformation of her hands. “It’s called murderer’s thumb,” she said, producing the digits in question. I had previously noticed that that her thumbs were small and stubby with shortened nails, although I never considered that a malformation. But she told us that people with this thumb condition have banded together to start a community page on Facebook — perhaps encouraged by the news that the actress Megan Fox was a fellow member.

Hands with clubbed thumbs

Murderer’s thumb — also called shovel thumb, toe thumb, Dutch thumb, hammer thumb, stub thumb, and potter’s thumb — goes by the medical appellation brachydactyly type D (BDD). It’s not terribly rare, appearing in around 0.4 percent of the population in the U.S., and in slightly higher frequencies in some other parts of the world. It’s an inherited trait that graces the thumbs of women more often than men.

BDD is completely harmless and even provides unexpected benefits in keyboard typing, video gaming, piano playing, and thumb-war battling. Some people, especially parents, find it cute.

In past centuries, though, the condition acquired a sinister reputation. The nineteenth-century European and American passion for categorizing racial groups and personal character through physical manifestations — physiognomy, craniometry, and phrenology are among these pseudo-scientific fields — branded the BDD thumb as a mark of primitive disposition, a sign of impulsive and unsophisticated thinking. Writers of popular detective novels sometimes scattered their stories with suspects with BDD to hint at criminal inclinations.

Palmists weigh in

In later decades, practitioners of palmistry took up the cause against BDD with even greater enthusiasm. Palm readers brought the term “murderer’s thumb” into the mainstream. In his 1901 manual The Laws of Scientific Hand Reading, William George Benham warns that clubbed thumbs are “dangerous companions…not to be trifled with at any time.” He further declares that “[m]any murderers have had clubbed thumbs…. Their brutal instincts being strong, jealousy most often has led them to fits of violent rage, and the terrible qualities of the clubbed thumb have given them passion and determination strong enough to take human life.”

Nine years later, the palmist Cheiro (a pseudonym of Louis Hamon) writes of people with murderer’s thumb: “If they are opposed they fly into ungovernable passions and blind rages. They have no control over themselves, and are liable to go to any extreme of violence or crime during one of their tempers.” Fortunately, says Cheiro, the owner of such a thumb cannot “plan out or premeditate a crime, for he would not have the determined Will or power of reason to think it out.”

As recently as 2011, in the book Practical Palmistry, Narayan Dutt Shrimal claims to have read the palms of 400 killers and “discovered that all had one common sign on their hands, that the murderer’s thumb was small and the tip of the thumb was flat, also that the nail of the thumb was small and more or less round in shape.”

Shrimal describes to perfection the thumbs of my daughter, who to the best of my knowledge has never killed in a fit of passion and years ago became a vegetarian out of compassion for the suffering of animals. Yet she is proud of her murderer’s thumbs.

Further reading:

Benham, William George. The Laws of Scientific Hand Reading. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1901.

Castriota-Scanderberg, Alessandro and Bruno Dallapiccola. Abnormal Skeletal Phenotypes: From Simple Signs to Complex Diagnoses. Springer, 2005.

Cheiro (Louis Hamon). Palmistry for All. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910.

A Forgotten Scroll, An Unforgettable Crime

By Eric Jager (Guest Contributor)

By Eric Jager (Guest Contributor)

In the 1660s, a curious parchment scroll was discovered at an old château in the south of France. It was a police report on the 1407 murder of Louis of Orleans, brother of the insane king, hacked to death one night in a Paris street. In it was an autopsy report, detailed notes on the case, and numerous witness statements taken by investigators. The scroll had been compiled by the city provost or chief of police, Guillaume de Tignonville. After thirty feet, it abruptly ended. Guillaume had sprung a trap eliciting a confession from a member of the royal family. He was now in danger, and the nation was headed for civil war.

A Rare Look into Medieval Investigations

The scroll, compiled in the turbulent days after the crime, reads like a police procedural, detailing how Guillaume and his officers closed the city gates, examined the crime scene, scoured Paris for evidence, and summoned dozen of ordinary Parisians to give statements. It offers a rare inside look at a medieval crime investigation, letting us hear the voices of long-dead Parisians caught up in great events and otherwise lost to history. We hear, for example, the vivid testimony of Jacquette Griffard, a shoemaker’s wife who watched in horror from her window as the band of masked assassins attacked Louis in the street below:

I saw the great lord on his knees in the middle of the street, in front of the door of the house of Marshal Rieux. His head was bare, and he was surrounded by seven or eight men. They all had masks — I couldn’t see their faces — and they were holding swords and axes. I couldn’t see the horses anymore. The men began striking the lord with their weapons. He raised his arm once or twice over his head, saying, “What is this? What are you doing?” No one answered.

Soon the lord fell down in the street and lay there, while the men kept hitting him with their swords, cut and thrust, as hard as they could, as if they were beating an old mattress.

I yelled out as loudly as I could: “Murder! Murder!”

One of the men in the street looked up and shouted: “ Shut up, you damned woman! Shut up!”

Along with Jacquette, more than three dozen witnesses were summoned — clerks, barbers, shopkeepers, and other housewives. Through their testimony we see the bustling neighborhood of the Marais before the crime, the moonless night of the murder, and the immediate aftermath as the assassins galloped away through the darkened streets. But these and other details were nearly lost when the scroll went missing at some point after the events. It was recovered years later largely by accident.

A Serendipitous Discovery

In the 1660s, Jean de Doat, a government official, directed a vast project to preserve thousands of old manuscripts scattered among archives and abbeys in southern France. With the support of Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Doat hired dozens of copyists who crisscrossed the land in search of France’s forgotten patrimony.

One of the manuscripts found by the scribes was the 1407 scroll. It turned up in Pau among the papers of Charles d’Albret, Constable of France at the time of Louis’s murder and the official who first alerted Guillaume to the crime. In 1666, a scribe made a copy that was sent to Paris for safekeeping but soon fell into obscurity. In the 1730s, the Doat collection was absorbed by the royal library. The copy, like the original, was nearly forgotten.

But someone had noticed it. In the 1740s, the royal librarian, the Abbé Sallier, mentioned the copy to a scholar named Pierre Bonamy, who had been looking for records of old houses in Paris. Retrieving the document, Bonamy was amazed to find that it contained long-lost details of Louis’s murder and the provost’s investigation. Like a torch suddenly ignited in the dark, new light fell on an infamous crime. (Imagine finding the Zapruder film of JFK’s assassination decades later in a drawer!)

Bonamy presented a paper to the Royal Academy in 1748, including excerpts from Guillaume’s report. One of the eyewitness accounts he read aloud was that of Jacquette, the shoemaker’s wife, bringing her voice back to life after centuries of silence. When Bonamy’s paper was printed six years later, the hidden history of Louis’s murder, at least in part, became available to the world.

Originals, Copies, and Textual Survival

But back in the south of France, the original scroll had fallen back into obscurity. Not until the 1860s did it come to light again, when Paul Raymond, a curator at the archives in Pau, stumbled upon it while cataloguing the Albret family papers. Like Bonamy more than a century earlier, Raymond recognized his stupendous find and promptly published a full transcript.

Thanks to Guillaume, one of history’s first detectives, we have the original scroll. And thanks to Doat, Bonamy, and Raymond, we have a transcript in Paris and another in print — and online. Anyone around the world can look it up and time-travel back to Paris six centuries ago. Who knows what else modern sleuths will discover there?

Eric Jager teaches medieval literature at UCLA. He is the author of four books, including Blood Royal and The Last Duel, a story of trial by combat in medieval France.

Eric Jager teaches medieval literature at UCLA. He is the author of four books, including Blood Royal and The Last Duel, a story of trial by combat in medieval France.