Holly Tucker's Blog, page 46

October 20, 2014

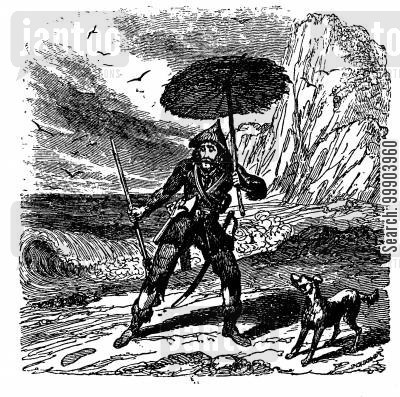

Robinson Crusoe and the Footprint in the Sand

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

Lately I’ve been researching old travel narratives from the 17th and 18th centuries, and rereading Robinson Crusoe. Then the other day I was watching The Apartment, Billy Wilder’s wonderful 1960 movie about corporate America. I was struck when Jack Lemmon says to Shirley MacLaine: “I used to live like Robinson Crusoe; I mean, shipwrecked among 8 million people. And then one day I saw a footprint in the sand, and there you were. ”

That got me thinking about that famous footprint-in-the-sand episode, when Crusoe first stumbles upon a sign of human habitation on his island. How many different ways has it been depicted and interpreted over the past 300 years? In the book, and in the illustration to the first editions, Crusoe is shocked, thrown off balance and appalled at the sight:

That got me thinking about that famous footprint-in-the-sand episode, when Crusoe first stumbles upon a sign of human habitation on his island. How many different ways has it been depicted and interpreted over the past 300 years? In the book, and in the illustration to the first editions, Crusoe is shocked, thrown off balance and appalled at the sight:

“I stood as one thunderstruck, or as if I had seen an apparition. … I came home not feeling, as we say, the ground I went on, but terrified to the last degree, looking behind me at every two or three steps …”

Imagining what type of person he might be about to encounter (cannibals?), Crusoe calms himself and tries to stave off nightmares by thinking that the footprint might in fact have been his own. But then, knowing that to be impossible, he decides that any fellow human is bound to at least resemble him in some way. When Friday finally appears in the flesh, Crusoe will quickly make him over into a loyal servant and shadow of himself.

Contemplative Crusoe

Subsequent illustrations of the episode have reflected a change in the way different generations of readers have approached it – Crusoe is no longer depicted as terrified, only curious, sometimes on bended knee like an explorer or tracker, examining the evidence more closely before deciding what to do. And modern editions of the story as presented to young readers seem to emphasize the humanity of the moment. Crusoe is lonely, longing for a friend, and Friday will become one. We no longer see images of the scene where Crusoe places his foot on the neck of the kneeling Friday, signifying the Englishman’s mastery over the black man whose footprint had frightened him.

Shipwrecked in Hawaii?

The script writers for the popular TV series Mad Men might have been playing around with Defoe’s iconic moment in an episode where Don Draper takes a trip to Hawaii. He comes back with an idea for an ad showing footprints in the sand, next to the discarded clothing of a businessman. Are the footprints those of another person? Or has this modern traveler decided to go native? Don’s clients reject the ad idea, saying the image is too ambiguous, and even potentially depressing, suggestive not of the liberation of the castaway, but of a suicide.

October 18, 2014

A Quest for Flavor

By Gastropod (Regular Contributor)

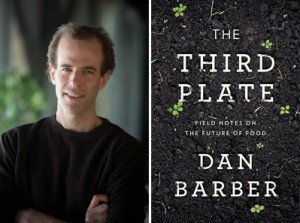

In this latest episode of Gastropod, chef and author Dan Barber takes listeners on a journey around the world in search of great flavor and the ecosystems that support it, from Spain to the deep South. You’ll hear how a carefully tended landscape of cork trees makes for delicious ham, and about a squash so cutting edge it doesn’t yet have a name, in this deep dive into the intertwined history and science of soil, cuisine, and flavor.

Ecosystem Cuisines

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time before refrigerators, before long-distance trucks and ships. Most people had to survive on food from their immediate surroundings, no matter how poor the soil or challenging the terrain. They couldn’t import apples from New Zealand and potatoes from Peru, or rely on chemical fertilizer to boost their yields.

From within these constraints, communities around the world developed a way of eating that Dan Barber calls “ecosystem cuisines.” Barber, the James Beard-award-winning chef of Blue Hill restaurant and author of the new book The Third Plate, spoke to Gastropod about his conviction that this historically-inspired style of cuisine can be reinvented, with the help of plant-breeders, his fellow chefs, and the latest in flavor science, in order to create a truly sustainable way to eat for the twenty-first century.

From within these constraints, communities around the world developed a way of eating that Dan Barber calls “ecosystem cuisines.” Barber, the James Beard-award-winning chef of Blue Hill restaurant and author of the new book The Third Plate, spoke to Gastropod about his conviction that this historically-inspired style of cuisine can be reinvented, with the help of plant-breeders, his fellow chefs, and the latest in flavor science, in order to create a truly sustainable way to eat for the twenty-first century.

Ecosystem cuisines, as Barber explains , survived in often harsh landscapes for hundreds or even thousands of years, because the local farmers cultivated a mutually beneficial community of plants and animals that grew well together, supported soil fertility, and could be combined in ways that still taste utterly fantastic today.

Barber became famous for his farm-to-table cooking—a style of cuisine that prioritizes serving local, seasonal food, and that has become increasingly popular across America as a sustainable, delicious way to eat. But, as he began to understand how ecosystem cuisines incorporated all the ingredients of a healthy landscape, he realized that the typical farm-to-table chef’s approach of only showcasing a region’s very best local products isn’t really sustainable at all.

For example, Barber told us that  the world-famous jamon iberico de bellota, Spain’s mouth-watering Iberian ham, simply could not exist if the local community didn’t also value, maintain, and consume the entire ecosystem around it. This landscape, a carefully tended combination of grasslands and widely spaced cork and holm oak trees, is called the dehesa in Spanish. As Barber explained, despite being a remote region with poor soils and a dry climate, the Spanish dehesa supports a thriving mix of pigs, sheep, and cows, olives, mushrooms, wild game and herbs, wheat—and people, whose dinner plates traditionally reflect all of the landscape’s products, rather than just its superstar ham.

the world-famous jamon iberico de bellota, Spain’s mouth-watering Iberian ham, simply could not exist if the local community didn’t also value, maintain, and consume the entire ecosystem around it. This landscape, a carefully tended combination of grasslands and widely spaced cork and holm oak trees, is called the dehesa in Spanish. As Barber explained, despite being a remote region with poor soils and a dry climate, the Spanish dehesa supports a thriving mix of pigs, sheep, and cows, olives, mushrooms, wild game and herbs, wheat—and people, whose dinner plates traditionally reflect all of the landscape’s products, rather than just its superstar ham.

Inspired by the dehesa, Barber has set himself (and anyone who cooks) an inspiring and intimidating goal: to invent thousands of entirely new cuisines for America—cuisines that include all the edible products of a healthy, ecologically balanced local landscape, and are actually more delicious than a cuisine that only relies a region’s most famous foods.

The Science Behind Great Flavor

The first chapter of our conversation with Dan Barber explores the particular environmental and cultural circumstances that helped establish these traditional ecosystem cuisines in the past. But Barber is very clear that he’s not advocating some kind of impossible return to a simpler time. Instead, as we go on to discuss in the episode’s second and third chapters, Barber is working with a variety of scientists at the cutting edge of their fields in his quest for truly great flavor.

In the book, this involves a visit to a futuristic hydrological engineering project in southern Spain, in which the flow of water through a series of 1920s-era canals has been reversed to revive one of Europe’s largest wetlands, creating a perfect habitat for both migrating birds and farm-raised sea bass that Barber describes as among the most delicious fish he has ever tasted. It also involves a series of failures in an innovative attempt to produce ethical foie gras, a bread raised using phytoplankton rather than yeast, and an impassioned argument for increased government support of agricultural research.

In the book, this involves a visit to a futuristic hydrological engineering project in southern Spain, in which the flow of water through a series of 1920s-era canals has been reversed to revive one of Europe’s largest wetlands, creating a perfect habitat for both migrating birds and farm-raised sea bass that Barber describes as among the most delicious fish he has ever tasted. It also involves a series of failures in an innovative attempt to produce ethical foie gras, a bread raised using phytoplankton rather than yeast, and an impassioned argument for increased government support of agricultural research.

In this Gastropod episode, however, we focus on the science behind two approaches to creating great flavor: soil health and plant breeding. With Barber as our guide, we tease out the complicated and barely understood relationship between a soil’s mineral content and the nutrient density and flavor of the crops it supports, as well as the emerging science of microbe-root relationships and plant health.

Finally, we look at what it takes to breed truly delicious crop varieties. Barber introduces us to new squash developed by Michael Mazourek at Cornell University that has yet to receive a name, but is “so delicious that it blows your mind.” Barber’s latest obsession, however, is a new variety of wheat, specially bred by Steve Jones at the Washington State Research and Extension Center to deliver intense flavor while growing well in the Hudson River valley. It’s called, to his great delight, “Barber wheat.”

Finally, we look at what it takes to breed truly delicious crop varieties. Barber introduces us to new squash developed by Michael Mazourek at Cornell University that has yet to receive a name, but is “so delicious that it blows your mind.” Barber’s latest obsession, however, is a new variety of wheat, specially bred by Steve Jones at the Washington State Research and Extension Center to deliver intense flavor while growing well in the Hudson River valley. It’s called, to his great delight, “Barber wheat.”

Dan Barber is a guest on the latest episode of Gastropod, a new podcast hosted by award-winning science journalist Cynthia Graber and Edible Geography-author Nicola Twilley. Listen to this episode to learn more surprising stories about the history and science of great flavor, including how the American Civil War can be traced back, in part, to a forgotten soil crisis, as well as the shocking research showing significant declines in the minerals in both American vegetables and soils over the past fifty years.

Dan Barber is a guest on the latest episode of Gastropod, a new podcast hosted by award-winning science journalist Cynthia Graber and Edible Geography-author Nicola Twilley. Listen to this episode to learn more surprising stories about the history and science of great flavor, including how the American Civil War can be traced back, in part, to a forgotten soil crisis, as well as the shocking research showing significant declines in the minerals in both American vegetables and soils over the past fifty years.

October 17, 2014

Every Pigeon Tells a Story

By Juliet Wagner (Regular Contributor)

Between 1903 and 1906, Julius Neubronner, a pharmacist in a small town near Frankfurt, would regularly receive prescriptions and deliver small quantities of medication to a nearby sanatorium by carrier pigeon. After a particular pigeon that had been missing for a few weeks returned to him in good health, Neubronner wondered where the truant pigeon had been, and his curiosity inspired him to design a special automatic camera-suit for his birds that took photographs beneath them as they flew.

Between 1903 and 1906, Julius Neubronner, a pharmacist in a small town near Frankfurt, would regularly receive prescriptions and deliver small quantities of medication to a nearby sanatorium by carrier pigeon. After a particular pigeon that had been missing for a few weeks returned to him in good health, Neubronner wondered where the truant pigeon had been, and his curiosity inspired him to design a special automatic camera-suit for his birds that took photographs beneath them as they flew.

A New Flock of Spies?

Although Neubronner’s original motivation was to spy on his pigeons, it soon became clear to him that the pigeons themselves could be employed as airborne spies, and he was quick to tout the potential military applications of pigeon photography after he patented his device in 1908. His design took advantage of the fairly consistent altitude of pigeon flight to calculate focal length, and different versions of the suit had different camera features. Neubronner also developed a mobile dovecote with an enlarged landing entrance to accommodate the extra bulk of his flying photographers’ gear.

The poor birds modeling the suits on these photographs were probably stuffed, but Neubronner did successfully demonstrate the camera-suit on live pigeons. He used beautiful images of the German landscape –askance and framed by the tips of the photographer’s wings—to prove it.

Drone Prototypes

The Prussian military was negotiating with Neubronner to purchase his camera-suit technology and team of pigeons when the First World War broke out in August 1914. Bowing to national emergency, Neubronner’s pigeons were drafted and reportedly tested with some success by the Prussian army, but were never used widely. The promise of small, reliable, unobtrusive airborne spies was not truly fulfilled until the widespread use of drones by the US military almost a century later.

No longer an exclusively military technology, drones are becoming common in much less ominous settings. Drone photography is now used for class photo group shots, for example, replacing the old-school photographer on her precarious stepladder, and is also applied to analyze football plays, supervise farmland and to entertain crowds at public events. In a reversal of Neubronner’s innovation, amazon.com has recently proposed using drones to deliver packages.

Like the humble pigeon, however, 21st century drones are not without predators. The latest online drone-video craze features impressive drone-eye-view hawk attacks.

For more on Julius Neubronner:

Franziska Brons, “Bilder im Fluge: Julius Neubronners Brieftaubenfotografie” Fotogeschichte: Beiträge zur Geshichte un Äesthetik der Fotografie, Jahrgang 26, Heft 100 (2006), pp. 17-36.

As well as a pharmacist and inventor, Neubronner was an amateur film enthusiast. A short film he made performing magic tricks in 1904 is viewable here (his pigeons feature!).

Additional images of Neubronner’s pigeons and the views they captured are available here.

Juliet Wagner is a Research Assistant Professor of History at Vanderbilt University, where she is also an active participant in colloquia in ‘Medicine, Health and Society’ and at the Penn Warren Humanities Center. She is currently completing the final touches on her first book, on film and shell shock during the First World War, which argues that the notion of “suggestion” was central to both trauma and cinema in the early twentieth century.

How I Write History…with Gary Krist

An Interview with Gary Krist (Guest Contributor)

Wo nders and Marvels: You began your career writing novels and short stories. What inspired you to start writing about history in the form of narrative nonfiction?

nders and Marvels: You began your career writing novels and short stories. What inspired you to start writing about history in the form of narrative nonfiction?

Gary Krist: Until I hit forty, I read–and wrote–mostly fiction. But at a certain point, I found I wanted to know more about how the world actually came to be, so I started reading history. And that interest soon bled over into my writing life. I began writing a historical novel, Extravagance, which took place partly in late-17th century London. I made several trips to the UK and discovered that I just loved the whole research process. So, after Extravagance, I decided to take the full leap to narrative history, and that’s where I’ve been for my last three books. I do think that I’ll write another novel at some point, but right now I feel I’ve found my true calling.

W&M: As an accomplished writer of fiction, how do you incorporate the art of storytelling when writing history?

Gary Krist: I want my readers to experience history with great immediacy, so I try to alternate background analysis with a series of unfolding foreground episodes that readers can really see and feel, as they would the episodes of a novel. But since I try to hold myself to strict standards of scholarship, I don’t have the freedom to invent dialogue or do extensive imaginary scene-setting. I’ve got to find all of that detail in the historical record. So I’m always on the lookout for things like memoirs, letters, court testimony, and newspaper interviews that can provide the specifics I need. Of course, such sources, like any others, are not necessarily gospel truth, so I have to weigh the reliability of every document. Sometimes I discuss this evaluation process in the endnotes, so readers can see how I make those decisions.

W&M: Does your writing process differ when writing fiction versus narrative nonfiction? How so?

Gary Krist: I always feel that I’m in the narrative business, whether I’m writing fiction or history. And the basics of creating an effective narrative are the same either way. You want to bring out the individuality and motivations of your characters; you want to ground those characters in a world with a vivid texture of sights, sounds, and atmosphere; and you want the action to unfold in a way that keeps readers engaged. But with narrative history, you have to do all of that with the elements of the actual historical record. It can be a challenge.

W&M: What advice do you have for writers who want to take a different approach to writing history?

Gary Krist: Narrative nonfiction history—the kind that aims at a popular audience but maintains high scholarly standards—is still a relatively new genre, so it’s important that writers make clear that they’re not doing New Journalism (with its freely fictionalized elements) or old-style “local-color” history (which dealt in unfootnoted folklore more than verifiable fact). Earning and keeping the trust of your audience is crucial to the success of any piece of narrative nonfiction; readers have to be convinced that what you’ve written is indeed what it purports to be—i.e., NONfiction. That’s why I labor over my endnotes. As a reader, I don’t like sketchy notes that just list a bunch of citations for an entire paragraph, without specifying what fact or quotation came from which source. So as a writer I try to pinpoint exactly where I found a particular detail. I also try to make my notes somewhat conversational, discussing, for instance, the pros and cons of various biographies of a particular figure in the story. “Transparency” is an overused buzzword these days, but I do think it’s something for any writer of nonfiction to strive for.

Gary Krist is the bestselling author of City of Scoundrels and The White Cascade, as well as several works of fiction. His new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, has just been published.

Gary Krist is the bestselling author of City of Scoundrels and The White Cascade, as well as several works of fiction. His new book, Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, has just been published.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Gary Krist’s’s new book Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”

October 15, 2014

Julia Pastrana, ‘bearded lady’

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

In February 2013 there was a big day for the ‘bearded lady': Julia Pastrana’s body was repatriated to her native Mexico and buried, her coffin covered with white roses. Julia, ‘the world’s ugliest woman’, suffered from excessive hair growth on her face. She was exhibited at freak shows by her impresario husband in the 1850s and, after her death in 1860, he went on travelling with her embalmed body, displayed so that audiences could now gaze at her without the embarrassment of her returning their stares. Rebecca Stern has listed the many parallels between Julia and the character Marian Halcombe in Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White, which was serialised in 1859-60. For example, we are told that Halcombe’s ‘complexion was almost swarthy, and the dark down on her upper lip was almost a moustache’, and that the viewer is ‘almost repelled by the masculine form and masculine look of the features in which the perfectly shaped figure ended’.

Julia was by no means the first such woman to be displayed. In the Renaissance, the three Gonzales ‘hairy girls’ were moved around the courts of Europe during the sixteenth century, like living items in a cabinet of curiosities. But it was in the mid-nineteenth century that the ‘bearded lady’ became a staple of the live freak show. The rise of the railway and the steam ship in the 1830s enabled such shows to take off, with performers being able to travel not just within one country, but also between nations. Nadja Durbach argued that the peak of their popularity came at a time of ‘modern and imperial self-fashioning’. Why ‘modern’? Because, scholars argue, the display of the ‘weird’ is part of modernity’s attempts to restrict the possibilities for individual variation. Not just the paying public, but also medical professionals, were interested in these variations.

While some such ‘women’ may have been men dressed in women’s clothing, many were not. Those displayed included people of uncertain sex – such as Gottlieb Göttlich, who travelled over Europe as medical experts failed to decide on the ‘true sex’ – as well women with various hormonal or genetic conditions who grew beards or were hairy all over. The ‘bearded lady’ was often shown smartly dressed, looking like a respectable woman of the time. This made the beard even more of a shock. Those with hair all over were shown in skimpy clothing and displayed as the ‘missing link’ with the animal kingdom; for example, both photographs and posters survive showing a woman who was exhibited from 1883 as ‘Krao’, and the posters were drawn to make her more hairy than she really was.

Were these people exploited, tragic figures, or were they in control and finding a way to make a living? Was this a career – or a form of slavery? Krao’s display coincided with the move for women’s rights in education and politics, making the ‘bearded lady’ a particularly worrying figure. In one cartoon of the period, a suffragette asks the bearded lady on display in a shop window ‘How did you manage it?’ The bearded lady has her travelling bag beside her; this shows that, in some ways, it is she rather than the suffragette who has the greater freedom.

To find out more:

Nadja Durbach, Spectacle of Deformity. Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2010.

Rebecca Stern, ‘Our bear women, ourselves. Affiliating with Julia Pastrana’ in Marlene Tromp (ed.), Victorian Freaks. The Social Context of Freakery in Britain, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2008, 200-233.

Merry Wiesner-Hanks, The Marvellous Hairy Girls, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 10 March 2013. Since then, I’ve extended my interest in the disruptive potential of the beard with a piece for The Conversation on the Conchita Wurst phenomenon.

October 14, 2014

World War I and the Rise of the Colt Pistol

By Peter Doyle (Guest Contributor)

+ A Giveaway

The Colt M1911 pistol – officially the Automatic Pistol, Calibre .45, M1911 – is one of the most famous weapons ever produced, a design classic that has been copied by many manufacturers the world over. Weighing some 2.44 lbs and measuring just 8.25 in long, the M1911 is both neat and robust. Semi-automatic the pistol is loaded from a seven round box magazine – which supplied the man-stopping .45 calibre bullets.

The Colt M1911 pistol – officially the Automatic Pistol, Calibre .45, M1911 – is one of the most famous weapons ever produced, a design classic that has been copied by many manufacturers the world over. Weighing some 2.44 lbs and measuring just 8.25 in long, the M1911 is both neat and robust. Semi-automatic the pistol is loaded from a seven round box magazine – which supplied the man-stopping .45 calibre bullets.

The M1911 grew out of a need for a weapon capable of delivering this stopping power for the US Army, which was engaged in battles against guerrillas in the Phillippines during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The US Government initiated weapons trials in 1906 with the specification that the pistol should be ‘no less that .45 calibre’, and that, ideally, it should be semi-automatic. The Colt bested five other pistols in the trials; and while 6,000 rounds were fired over the two days from a single weapon, it did not misfire or jam. This level of robustness would serve it well in the world conflict, and it entered US Service in 1911.

The pistol is also perhaps representative of the weapons the United States brought to the war theatre in 1917. Robust, reliable, no-nonsense, in the right hands, the Colt was capable of hard work. In the hands of Sergeant Alvin York, celebrated son of Tennessee and winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor while attacking a German machine gun position, it was deadly. Innovative in design, it was joined by the M1895 Winchester ‘trench’ shotgun, and efficient weapon in the confines of a trench or dug-out, but one that garnered complaint from the Germans, aimed at the United States through diplomatic channels as being ‘inhumane’ – in a war that produced chemical weaponry. Our colt is representative of the ever more efficient manner in which soldiers were killed in this most industrialized of all conflicts.

Peter Doyle is a military historian and geologist, specializing in battlefield terrain, and the author of World War I in 100 Objects (Plume Books.) He has appeared on television as a contributor on television and in documentaries including WWI Tunnels of Death, The Big Dig, and Battlefield Detectives. He is currently Visiting Professor at University College London.

Peter Doyle is a military historian and geologist, specializing in battlefield terrain, and the author of World War I in 100 Objects (Plume Books.) He has appeared on television as a contributor on television and in documentaries including WWI Tunnels of Death, The Big Dig, and Battlefield Detectives. He is currently Visiting Professor at University College London.

W&M is excited to have three (3) copies of Peter Doyle’s new book World War I in 100 Objects for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on October 31 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Monthly Book Giveaways

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

October Book Giveaways

Jack Zipes, “The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition”

Peter Doyle, “World War I in 100 Objects”

Laura Auricchio, “The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered”

Gary Krist, “Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans”

October 13, 2014

Of Cabbages

By Helen King (Regular Contributor)

In a recent episode of the British TV comedy series, Plebs, which follows the adventures of two young Roman men and their slave in the big city, one of the many interesting remedies of ancient medicine featured, although not in a standard role!

The series is built on finding entertaining parallels between its version of ancient Rome, and modern city life. So, one of characters works in an office, where he is the copier, while another is the shredder. No office would be complete without one of each! In a recent episode one young man started driving lessons – in order to drive a chariot. Three-point turns posed a particular problem.

In the episode “The Baby”, the slave is trying to make sense of the new rules on recycling rubbish.

“The bin in the middle, that’s your everyday household products.

Right.

That’s your pottery shards, your sackcloth, papyrus and whatnot.

Household products, yeah.”

To his surprise he finds an abandoned baby in the rubbish and the rest of the episode is built around his attempts to care for her. One problem of course is diapers; and his solution is to use cabbage leaves.

“Are you sure a cabbage is gonna work?

Course. It’s nature’s nappy.”

This made me laugh even more than the rest of the episode. It brought back to me memories of teaching Roman medicine to Classics students, when I encouraged them to do a presentation to the rest of the class that went beyond the usual “reading out some notes and showing a PowerPoint” (yawn) method. One particularly innovative group acted out a “consulting the physician scene”, with various “patients” going to different Roman physicians whose theories we know, and getting suggestions for treatment. One thing all the students remembered was that traditional Roman medicine seems to have been big on cabbage. So, at the end of every imaginary consultation, the student playing the physician added “oh, and have some of this, it’s brilliant” while throwing a cabbage towards the patient.

So, why cabbage? It is an interesting remedy not because of the inevitable websites claiming that “modern nutritional research completely validates” ancient beliefs, but rather because it brings out our difficulties in knowing about the medicine of the past.

On the one hand, the Roman statesman Cato tells us that this is a sure-fire cure for many things. It is great for the digestion or for colic, and an excellent laxative. Different varieties have different levels of power, and the wild is best of all. Cabbage is good crushed and used as a poultice; it cures sores, boils and even dislocations. It cures headaches and pain in the eyes. Most effective of all is the warmed-up urine of someone who regularly eats cabbage. It’s an excellent fluid for bathing babies (funnily enough, this particular recommendation does not feature in modern internet eulogies of the plant!), and women can also use it as a personal hygiene product. It can be rolled up into a pellet and placed to heal an anal fistula (ouch), while dried cabbage can be snorted like snuff to cure a nasal polyp.

This interest in a common vegetable fits well with other Roman remedies: wool, milk, the simple products of the farm which every Roman – including those, like Cato, from the elite – saw as part of their birthright and their identity as true Romans. Nothing could be further from the fancy and expensive remedies they associated with those wordy, dangerous ancient Greek physicians!

But is it so simple? Should we resist classifying this list of medicinal uses of cabbage as characteristic of traditional Roman medicine? Because, on the other hand, we know from the later Roman writer Pliny the Elder that a Greek writer, Chrysippus, wrote a whole book on cabbage. Cato is not a neutral source (who is?). He was rabidly anti-Greek. In the biography of him written by Plutarch it is said that he only learned the language late in his life. But Plutarch also observes that Cato’s works include ‘Greek sentiments and stories, and many literal translations from the Greek have found a place among his maxims and proverbs’. This suggests that, while Cato’s public pronouncements were very anti-Greek, in fact he knew Greek literature pretty well. So perhaps Cato’s normal distaste for Greek writers is misleading, and the praise of cabbage came not from traditional Roman household remedies, but rather from a book; and a Greek one at that.

October 12, 2014

How I Write History…with Adrienne Mayor

An Interview with Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: Can you remember one of the first historical figures that captured your imagination?

Wonders & Marvels: Can you remember one of the first historical figures that captured your imagination?

Adrienne Mayor: As a girl in South Dakota I was enchanted by a book with a zebra stripe cover called “I Married Adventure” by Osa Johnson, published in 1940. Originally from Kansas, Osa and her husband Martin were adventurers, naturalists, and documentary film pioneers who explored exotic, faraway Africa, the South Pacific, and Borneo in 1917-37. They flew amphibious biplanes; lived in tents; befriended head hunters, cannibals, and pygmies; and encountered dangerous wild animals–with their primitive Eastman-Kodak movie cameras whirring all the while. They produced the first aerial films and talkies ever made in Africa. I read Osa’s memoirs countless times, day dreaming and poring over the sepia photos.

The first historical figure from classical antiquity to capture my attention was also a historian. My favorite ancient writer is still Herodotus, the insatiably curious Greek from Persian Halicarnassus (Bodrum, Turkey) who traveled to exotic lands, interviewing “barbarians” about their history and customs, and captivated the Athenians of the fifth century BC with his stories.

The first historical figure from classical antiquity to capture my attention was also a historian. My favorite ancient writer is still Herodotus, the insatiably curious Greek from Persian Halicarnassus (Bodrum, Turkey) who traveled to exotic lands, interviewing “barbarians” about their history and customs, and captivated the Athenians of the fifth century BC with his stories.

W&M: When did you decide to become a historian? When did you begin to feel like a historian?

Adrienne Mayor: It was my obsession with the fabulous gold-guarding Griffin of Greek lore that turned me into a historian. As I tracked this unknown creature, untangling threads and recovering and analyzing evidence long buried in ancient Greek and Roman art and literature and Scythian artifacts and traditions and integrating all this with modern paleontological discoveries of dinosaur skeletons in Central Asia, I really became a historian of human curiosity.

W&M: Can you describe the process of finding and researching your first book topic? How did that compare to doing The Amazons?

I began gathering material for my first book, “The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times” (2000) on my first trip to Greece in 1978 and began the organized research in 1990s, while I was working as a freelance copyeditor. This was long before email and the Internet, Google Scholar searches, and JSTOR had not yet been invented. And I lived in Montana then, far from university libraries. So I haunted museums and library stacks in every city I visited, made myriad interlibrary loan requests, and mailed typewritten letters to paleontologists and other scholars, waiting months for their replies to my queries. Needless to say, researching and writing The Amazons was a totally different experience, with so much far-ranging, international art and written sources available online.

W&M: What is the best or worst advice you’ve ever gotten as a writer?

Adrienne Mayor: One piece of advice was something I resisted at first: Make an outline. I considered outlines boring but once I learned that they can be continually revised I was sold. The old cliché is the advice to “write what you know.” Instead I would say: first chose a topic that you yourself want to learn more about, delve deeply into that subject, and then write what you know. That way your passion to discover and convey something new will shine through.

Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014). Her biography of Mithradates VI of Pontus, The Poison King (2009) was a nonfiction finalist for the National Book Award. Her other books are The First Fossil Hunters, Fossil Legends of the First Americans, and Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World.

Adrienne Mayor is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014). Her biography of Mithradates VI of Pontus, The Poison King (2009) was a nonfiction finalist for the National Book Award. Her other books are The First Fossil Hunters, Fossil Legends of the First Americans, and Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World.

Of cabbages

By Helen King

In a recent episode of the British TV comedy series, Plebs, which follows the adventures of two young Roman men and their slave in the big city, one of the many interesting remedies of ancient medicine featured, although not in a standard role!

The series is built on finding entertaining parallels between its version of ancient Rome, and modern city life. So, one of characters works in an office, where he is the copier, while another is the shredder. No office would be complete without one of each! In a recent episode one young man started driving lessons – in order to drive a chariot. Three-point turns posed a particular problem.

In the episode ‘The Baby’, the slave is trying to make sense of the new rules on recycling rubbish.

“The bin in the middle, that’s your everyday household products.

Right.

That’s your pottery shards, your sackcloth, papyrus and whatnot.

Household products, yeah.”

To his surprise he finds an abandoned baby in the rubbish and the rest of the episode is built around his attempts to care for her. One problem of course is diapers; and his solution is to use cabbage leaves.

“Are you sure a cabbage is gonna work?

Course. It’s nature’s nappy.”

This made me laugh even more than the rest of the episode. It brought back to me memories of teaching Roman medicine to Classics students, when I encouraged them to do a presentation to the rest of the class that went beyond the usual ‘reading out some notes and showing a PowerPoint’ (yawn) method. One particularly innovative group acted out a ‘consulting the physician’ scene, with various ‘patients’ going to different Roman physicians whose theories we know, and getting suggestions for treatment. One thing all the students remembered was that traditional Roman medicine seems to have been big on cabbage. So, at the end of every imaginary consultation, the student playing the physician added ‘oh, and have some of this, it’s brilliant’ while throwing a cabbage towards the patient.

So, why cabbage? It is an interesting remedy not because of the inevitable websites claiming that ‘modern nutritional research completely validates’ ancient beliefs, but rather because it brings out our difficulties in knowing about the medicine of the past.

On the one hand, the Roman statesman Cato tells us that this is a sure-fire cure for many things. It is great for the digestion or for colic, and an excellent laxative. Different varieties have different levels of power, and the wild is best of all. Cabbage is good crushed and used as a poultice; it cures sores, boils and even dislocations. It cures headaches and pain in the eyes. Most effective of all is the warmed-up urine of someone who regularly eats cabbage. It’s an excellent fluid for bathing babies (funnily enough, this particular recommendation does not feature in modern internet eulogies of the plant!), and women can also use it as a personal hygiene product. It can be rolled up into a pellet and placed to heal an anal fistula (ouch), while dried cabbage can be snorted like snuff to cure a nasal polyp.

This interest in a common vegetable fits well with other Roman remedies: wool, milk, the simple products of the farm which every Roman – including those, like Cato, from the elite – saw as part of their birthright and their identity as true Romans. Nothing could be further from the fancy and expensive remedies they associated with those wordy, dangerous Ancient Greek physicians!

But is it so simple? Should we resist classifying this list of medicinal uses of cabbage as characteristic of traditional Roman medicine? Because, on the other hand, we know from the later Roman writer Pliny the Elder that a Greek writer, Chrysippus, wrote a whole book on cabbage. Cato is not a neutral source (who is?). He was rabidly anti-Greek. In the biography of him written by Plutarch it is said that he only learned the language late in his life. But Plutarch also observes that Cato’s works include ‘Greek sentiments and stories, and many literal translations from the Greek have found a place among his maxims and proverbs’. This suggests that, while Cato’s public pronouncements were very anti-Greek, in fact he knew Greek literature pretty well. So perhaps Cato’s normal distaste for Greek writers is misleading, and the praise of cabbage came not from traditional Roman household remedies, but rather from a book; and a Greek one at that.

October 9, 2014

The Man Who Played Hitler

By Jack El-Hai (Regular Contributor)

As a schoolboy, Bobby Watson sold peanuts amid the laughs and groans in the Olympic Theater in Springfield, Illinois. He soon became a vaudevillian himself, joined a traveling medicine show, and struggled to the stages of Broadway by the time he was 30. There Watson made his mark as a musical performer and comedian, performing in such shows as The Rise of Rosie O’Reilly, American Born, and The Greenwich Village Follies.

Bobby Watson as Adolf Hitler in the 1943 movie Natzy Nuisance. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Who could have guessed that the prat-falling and facially expressive actor would someday become best known for his repeated portrayals of the world’s most reviled leader, Adolf Hitler?

Germany’s führer had first become actor’s fodder in 1935, when the actor Konparu Minamizato played him in the little-seen Japanese short film Uma Kaeru. Five years later, in his most commercially successful film The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin appeared as Hitler and famously performed a mock ballet with a floating globe.

At about the same time, however, someone noticed that Watson — already a veteran of dozens of minor film comedies — bore a strong resemblance to Hitler. When he donned a National Socialist costume, brushed across his hair, and sported the distinctive Hitlerian mustache, the similarity was remarkable. Watson appeared as the Nazi for the first time in a Three Stooges short titled You Natzy Spy, which was followed by another Moe, Larry, and Curly comedy called I’ll Never Heil Again.

From those roles as Hitler, Watson was off and running. He impersonated Hitler many times in the years that followed, in such films as Hitler: Dead or Alive (1942), The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), The Hitler Gang (1944), A Foreign Affair (1948), The Story of Mankind (1957), On the Double (1961), and finally The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962). Only Watson’s death in 1965 ended the streak.

Watson, it should also be remembered, acted in many movies without wearing the swastika armband. He was an Ozmite in The Wizard of Oz and a diction coach in Singin’ in the Rain, and he wrote three comedies that were produced during the 1930s.

After Watson, many more actors chewed through parts as the German leader. Among the best known are Billy Frick (who only appeared in films once not as Hitler), Anthony Hopkins, Alec Guinness, Michael Sheard, Ian McKellen, and Derek Jacobi. None of these great actors looked the part more than Watson. For the rest of human history, Hitler’s image in newsreels and Leni Riefenstahl documentaries will compete against the comic portrayals of the boy from Springfield.

Sources:

Bakke, Dave. “Famous Springfieldians.” Springfield State Journal-Register, November 6, 2011.

Mitchell, Charles P. The Hitler Filmography: Worldwide Feature Film and Television Miniseries Portrayals, 1940 through 2000. McFarland, 2002.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 8 February 2013.