Holly Tucker's Blog, page 48

September 22, 2014

First Century Revolutionaries: The Trung Sisters of Vietnam

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

In 39 CE, two young women led Vietnam in its first rebellion against the Chinese empire, which had then ruled the country for 150 years.

Trung Trac and Trung Nhi were born in a small town in north Vietnam around 14 CE, the daughters of a Vietnamese lord who served as a prefect under the Chinese. According to legend, the sisters were trained in the arts of war by their mother.*

In 36 CE, a new, more oppressive, governor, To Dinh (aka Su Ting) took over the province. He demanded bribes and raised taxes on salt** . He taxed peasants for fishing in the rivers. In short, he was just the type of greedy and inept official who triggers rebellions in classic Chinese historiography.

Trung Trac, together with her husband Thi Sách, plotted to mobilize the local aristocracy to revolt. Learning of their plots and assuming that Thi Sách was the driving force of the conspiracy, To Dihn had him arrested and hung his body from the city gates as a warning to other would-be rebels.

To Dinh’s efforts to put down the rebellion by cutting off its head back-fired. Instead of giving up, the sisters raised an army of 80,000 troops, most of them in their twenties and a large number of them women.*** Their elderly mother served as one of their generals.

The Trungs and their untrained army drove the Chinese from Vietnam, liberating sixty-five strongholds along the way, and created a new state that stretched from Hue in the south into southern China. To Dinh was so terrified that he disguised himself by shaving off his hair and fled the country in secret.

For two years the Trung sisters ruled their newly independent kingdom unchallenged. In 41 CE, the Chinese emperor sent an army commanded by one of his best generals to reconquer Vietnam. For two years, the sisters defended their borders against the Chinese, but eventually they were worn down by the empire’s military and financial superiority. The Trungs fought their last battle near modern Hanoi in 43 CE. Thousands of Vietnamese soldiers were captured and beheaded and more than 10,000 surrendered.

The Trung sisters were not among those who surrendered. Instead, they committed suicide, which the Vietnamese believed was the more honorable option. Some sources say they drowned themselves in the Hát River; others claim they floated up into the clouds.

In the centuries that followed, the Trung sisters were held up as idealized examples of national courage in the struggle against first Chinese and later French domination. Over time,a Buddhist religious cult grew up around their memory and temples were built in their honor. Today they are remembered as national heroines in Vietnam, where the anniversary of their suicide is a national holiday.

* It may well be true, but this kind of thing has to be taken with a whole shaker of salt. As Antonia Fraser points out in The Warrior Queens, the Tomboy Syndrome is a standard trope in stories of women warriors.

**Always a bad idea. Salt is more than just a condiment.

***Vietnamese stories emphasize the heroism of the young women in the Trung’s army: one, General Phung Thi Chinh is said to have given birth on the battlefield, strapped the infant to her back, and continued fighting.

1st Century Revolutionaries: The Trung Sisters of Vietnam

By Pamela Toler (Regular Contributor)

In 39 CE, two young women led Vietnam in its first rebellion against the Chinese empire, which had then ruled the country for 150 years.

Trung Trac and Trung Nhi were born in a small town in north Vietnam around 14 CE, the daughters of a Vietnamese lord who served as a prefect under the Chinese. According to legend, the sisters were trained in the arts of war by their mother.*

In 36 CE, a new, more oppressive, governor, To Dinh (aka Su Ting) took over the province. He demanded bribes and raised taxes on salt** . He taxed peasants for fishing in the rivers. In short, he was just the type of greedy and inept official who triggers rebellions in classic Chinese historiography.

Trung Trac, together with her husband Thi Sách, plotted to mobilize the local aristocracy to revolt. Learning of their plots and assuming that Thi Sách was the driving force of the conspiracy, To Dihn had him arrested and hung his body from the city gates as a warning to other would-be rebels.

To Dinh’s efforts to put down the rebellion by cutting off its head back-fired. Instead of giving up, the sisters raised an army of 80,000 troops, most of them in their twenties and a large number of them women.*** Their elderly mother served as one of their generals.

The Trungs and their untrained army drove the Chinese from Vietnam, liberating sixty-five strongholds along the way, and created a new state that stretched from Hue in the south into southern China. To Dinh was so terrified that he disguised himself by shaving off his hair and fled the country in secret.

For two years the Trung sisters ruled their newly independent kingdom unchallenged. In 41 CE, the Chinese emperor sent an army commanded by one of his best generals to reconquer Vietnam. For two years, the sisters defended their borders against the Chinese, but eventually they were worn down by the empire’s military and financial superiority. The Trungs fought their last battle near modern Hanoi in 43 CE. Thousands of Vietnamese soldiers were captured and beheaded and more than 10,000 surrendered.

The Trung sisters were not among those who surrendered. Instead, they committed suicide, which the Vietnamese believed was the more honorable option. Some sources say they drowned themselves in the Hát River; others claim they floated up into the clouds.

In the centuries that followed, the Trung sisters were held up as idealized examples of national courage in the struggle against first Chinese and later French domination. Over time,a Buddhist religious cult grew up around their memory and temples were built in their honor. Today they are remembered as national heroines in Vietnam, where the anniversary of their suicide is a national holiday.

* It may well be true, but this kind of thing has to be taken with a whole shaker of salt. As Antonia Fraser points out in The Warrior Queens, the Tomboy Syndrome is a standard trope in stories of women warriors.

**Always a bad idea. Salt is more than just a condiment.

***Vietnamese stories emphasize the heroism of the young women in the Trung’s army: one, General Phung Thi Chinh is said to have given birth on the battlefield, strapped the infant to her back, and continued fighting.

September 18, 2014

Beauty Secrets of the Ancient Amazons

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

By Adrienne Mayor (Regular Contributor)

Galloping for miles on tough ponies, hunting, making war, marauding, and plundering, hot and dry in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter —life on the Scythian steppes was dirty, dusty work for nomad men and the women known to the ancient Greeks as Amazons. How did the saddle-sore Amazons and their male companions relax and tend to their bodies? For Scythians, bathing was a special occasion usually undertaken as a purification before funerals in the spring.

The Greek historian Herodotus (ca 450 BC) describes the Scythian-style toilette. Their unusually refreshing sauna sounds like a New Age spa treatment.

First the Scythians wash their heads with soap and water. But, notes Herodotus, they never wash their bodies this way. In order to cleanse their bodies, they fix in the ground three long sticks inclined towards one another to make a tipi-like booth. Large pieces of woolen felts are stretched over the poles, overlapping to fit as close as possible. Inside the tipi is a large stone bowl of red-hot stones. The men and women enter the felt tipi and toss handfuls of hemp-seeds onto the red-hot stones. (Cannabis grows wild on the steppes.) The smoke produces such a delightful vapor as no Grecian vapor-bath can exceed, remarks Herodotus. The Scythians shout for joy, and this intoxicating steam- bath serves them instead of a water-bath.

Then Herodotus divulges a recipe for an Amazon beauty mask.

The women make a mixture of cypress, cedar, and frankincense. They pound these ingredients into a paste on a rough stone, adding a little water. When this substance takes on a smooth, thick consistency, they cover their faces, and indeed their whole bodies, with the paste and retire for the night. When they remove the plaster on the next morning, comments Herodotus, a sweet odor is imparted to them and their skin is clean and glossy.

Today, all three of these ingredients are used in perfumes, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Cedar and cypress trees grow at high altitudes, as easily available to the Scythian nomads as local cannabis plants. Fragrant cedar and cypress oils have antiseptic qualities, helpful in fighting infection. Both are astringents for reducing oily skin, employed today against acne and dermatitis.

Small lumps of frankincense, the aromatic resin of Boswellia trees of the Arabian desert, would have been a precious trade commodity, available from merchants on the Silk Routes across Central Asia. It appears in ancient Egyptian recipes for beauty masks for toning and smoothing scars. Frankincense has antiseptic, anti-inflammatory properties, and is found in modern beauty products reputed to rejuvenate aging skin.

Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World (2014) and The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 6 September 2012.

W&M is excited to have five (5) copies of Adrienne Mayor’s new book The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World for this month’s giveaway! Be sure to enter below by 11:00pm EST on September 30 to qualify (your entry includes a subscription to W&M Monthly).

Please note that, at this time, we can only ship within the US.

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

September Book Giveaways

Ted Steinberg, “Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York”

Adrienne Mayor, “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World”

September 14, 2014

Is ISIS Unique? Armed Tourism, Then and Now

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor) and Arthur A. Goldsmith

Among this summer’s many dramatic international news stories, perhaps none stands out more prominently than the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)—a development aided by the presence of volunteer fighters from Europe, North America and even Australia. Few Western observers anticipated that so many young men (and this does seem almost exclusively a youthful male phenomenon) could be motivated to leave home and willingly risk their lives abroad in a violent political struggle in which they have no direct stake.

Explanations for today’s “armed tourism” often focus on contemporary globalization and technological innovations, especially social media, YouTube, smart phones, and increasingly realistic violent video games. Young people, it is said, spend too much time surfing the web. Modern aircraft make it easy for some of the misfits to escape to a war zone. But is armed tourism as novel as the conventional wisdom seems to believe?

Ideological Travelers to Spain

Ideological Travelers to Spain

In fact, Parliamentary backbencher Winston Churchill coined the term “armed tourist” 80 years ago. He used it to refer to the international combatants then flocking to the Spanish Civil War—the 1930’s rough equivalent to today’s conflict in Iraq and Syria. Religious and political principles drove many of the fighters to Spain, although a desire for adventure and new experiences (as well as high unemployment) must have played a role as well. France’s military attaché in Madrid at the time, Lieutenant-Colonel Henri Morel came up with perhaps an even more apt term than Churchill did. He labeled the volunteers “voyageurs en idéologie.”

The ideological imperatives behind the Spanish Civil War were obviously quite distinct from today’s Islamist causes, but there are interesting parallels nonetheless. Nationalist rebels wanted to overthrow the constitutional republic in Spain. Armed tourists who joined this side of the fight frequently had ties to the Catholic Church or to local fascist organizations. Examples include the French Jeanne D’Arc unit, the Irish Brigade, and the Romanian Legion. Russians, Americans, Finns, Turks, Greeks, Cubans, and many others joined the Nationalist cause. The primary impetus seems to have been moral belief, although there were certainly many opportunistic mercenaries and adventurers among their ranks.

Volunteerism across the Ideological Spectrum

Perhaps Spain’s best known ideological travelers fought against the Nationalists on the Republican side. Known as the International Brigade, numerous volunteer groups emerged that were committed to defending democracy in Spain. The American unit was the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. Other pro-Republican soldiers hailed from Britain and Brazil, Poland and Mexico, Russia and Yugoslavia—some fifty countries in all. Among their ranks were communists, anarchists, and social democrats.

Perhaps Spain’s best known ideological travelers fought against the Nationalists on the Republican side. Known as the International Brigade, numerous volunteer groups emerged that were committed to defending democracy in Spain. The American unit was the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. Other pro-Republican soldiers hailed from Britain and Brazil, Poland and Mexico, Russia and Yugoslavia—some fifty countries in all. Among their ranks were communists, anarchists, and social democrats.

State sponsors helped both the leftist and rightwing combat units, as is usually the case with private militias in our era, but the sponsors often lost control over their clients. In total over 60,000 people fought with the International Brigade between 1936 and 1939. Perhaps twice as many volunteers from around the world waged war on the Nationalist side. These numbers dwarf the international enlistment figures reported for ISIS and rival groups today.

As is the case among contemporary jihadists, factionalism was ever present with Spain’s volunteer militias. Historians still debate whether greater cohesiveness among the leftwing forces would have changed the outcome of the Spanish Civil War. Probably the decisive factor, however, was Germany and Italy’s direct intervention on behalf of the rebels.

For further reading: Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, rev. ed. (New York: Random House, 2001); Christopher Othen, Franco’s International Brigades: Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War, rev. ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

How I Write History…with Chet Van Duzer

An Interview with Chet Van Duzer (Guest Contributor)

An Interview with Chet Van Duzer (Guest Contributor)

Wonders & Marvels: Can you tell us about your first experience in an archive?

Chet Van Duzer: One of my most memorable early experiences was consulting a 14th century nautical chart in the British Library. I had arrived in London from California the day before, and thus was jetlagged, but with the thrill of seeing that map up close and in person my fatigue vanished. The immediacy of my interaction with the document—not just the pleasure of appreciating the textures and colors, but also the satisfaction of being able to study the chart without wondering whether a problem with the reproduction or the digital image that was obscuring details—brought an excitement that I’ll never forget.

W&M: What sparked your interest in cartography?

Van Duzer: I first became interested in maps during a visit to the Vatican Museums in 1997. I saw a manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography from the mid 15th century on display. It was open to the folios immediately following the standard Ptolemaic world map, and on those folios a later artist had added a second world map in about 1530. At that time, which was long before the discovery of Antarctica or Australia, many geographers and cartographers believed that there was a continent in the far south, probably to balance the landmasses in the north, and on maps from that period one sometimes sees a continent, basically a big island, near the South Pole. This map on display in the Vatican Museums had a hypothetical southern continent, but in this case, rather than being a big island, it was huge ring of land around the South Pole. That really inspired my curiosity. Granted that one believed that there had to be land in the far south, how could one conclude that it was in the shape of a huge ring, with open water at the South Pole? So I started investigating, and that study drew me to devote more and more of my energy to old maps. I like the fact that they have curious features that seem at first glance to defy explanation; usually in fact there is a very good reason for those features, but one must find the explanation through research.

Van Duzer: I first became interested in maps during a visit to the Vatican Museums in 1997. I saw a manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography from the mid 15th century on display. It was open to the folios immediately following the standard Ptolemaic world map, and on those folios a later artist had added a second world map in about 1530. At that time, which was long before the discovery of Antarctica or Australia, many geographers and cartographers believed that there was a continent in the far south, probably to balance the landmasses in the north, and on maps from that period one sometimes sees a continent, basically a big island, near the South Pole. This map on display in the Vatican Museums had a hypothetical southern continent, but in this case, rather than being a big island, it was huge ring of land around the South Pole. That really inspired my curiosity. Granted that one believed that there had to be land in the far south, how could one conclude that it was in the shape of a huge ring, with open water at the South Pole? So I started investigating, and that study drew me to devote more and more of my energy to old maps. I like the fact that they have curious features that seem at first glance to defy explanation; usually in fact there is a very good reason for those features, but one must find the explanation through research.

W&M: What is one research or writing related habit that is crucial to a good work-day?

Van Duzer: While working on one project, I always like to make at least some progress on future projects each day.

W&M: What advice do you have for beginning researchers entering libraries and archives?

Talk to colleagues who have worked in the archive before, and contact the relevant curator well in advance of your visit to ask about the most important documents you will be working on. Every archive has its bureaucratic frustrations and also its unique advantages, and advance knowledge of these can be extremely helpful. Contacting the curator ahead of time may seem superfluous, but it is better to be sure that the document you want to consult is not in conservation or away on exhibition, or to know that you need a special letter of recommendation in order to see it, than to discover these things only after arriving.

Chet Van Duzer studied at UC Berkeley and has published extensively on medieval and Renaissance maps, particularly those of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He is the author of Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, which will be released in paperback this month.

Chet Van Duzer studied at UC Berkeley and has published extensively on medieval and Renaissance maps, particularly those of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He is the author of Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, which will be released in paperback this month.

September 11, 2014

Let Them Eat Hair Garnishes

By Carlyn Beccia (Guest Contributor)

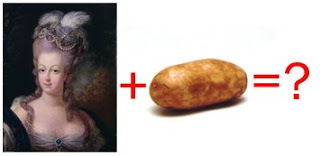

What do Marie Antoinette’s infamous pouf and the starchy tuberous crop fruit known as the potato have in common? Read more to find out…

What do Marie Antoinette’s infamous pouf and the starchy tuberous crop fruit known as the potato have in common? Read more to find out…

We tend to associate the potato more with Ireland and England than we do with France and that may be because the humble spud had a very rocky start with French Parisians. Although already widely accepted in England, the potato did not come to France until around 1600.1 Still, no respectable royal would dare to eat the strange, dirty, lumpy looking spud. The potato became so feared that in 1619 it was banned from Burgundy, France because it was rumored to cause leprosy. It all made perfect sense to 16th century scholars. The potato looked like leprosy so therefore it must cause leprosy.

The leprosy spud finally got an image makeover in the 18th century with the help from a potato propagandist and French chemist named Antoine-Auguste Parmentier. Parmentier threw some fabulous parties and invited the French upper class to taste his potato creations. At one of these parties, Parmentier gave Louis XVI a bouquet of potato flowers. Knowing his wife’s proclivity for putting vegetables in her hair, Louis thoughtfully placed one delicate, purple sprig in Marie Antoinette’s pouf. Thereafter, the potato may not have become a fashion accesory, but it did become the new, hot food delicacy among the upper class.

The potato then went on to feed the French peasants and everyone loved their queen and…lived happily ever after.

Ok, not exactly. Unfortunately, it took a few bread shortages, a nasty revolution, and some beheaded monarchs for the government to finally see the potato’s full potential for feeding the rest of the starving country. In 1794, a year after Marie Antoinette was beheaded, the queen’s beloved flowerbeds in the Tuileries were plowed over to make way for the purple blossoms that would feed a nation and become one of France’s biggest exports.

Carlyn Beccia is author of The Raucous Royals and Who Put the B in the Ballyhoo? and I Feel Better with a Frog in My Throat: History’s Strangest Cures. She writes about the scandals, rumors, and gossip of royalty on her fabulous blog. You’ll recognize Carlyn’s art here on Wonders & Marvels; she designed our fabulous logo, among many other wonderful things!

Notes:

(1) Some historians have blamed the slower populations grown of France in the 18th century to their dependence of grain while other countries had the starchy potato to fall back on. In reverse to France’s grain dependency, reliance on the potato backfired in Ireland during the Great Potato Famine. (2) This was at a time when walnuts were eaten to treat headaches because they looked like a brain and eating the brains of another animal would make you smarter.

Sources and Further Reading:

Langer L. William, “American Foods and Europe’s Population Growth 1750-1850.” Journal of Social History 8.2 (1975): 51-66.

Salaman N. Redcliffe, The History and Social Influence of the Potato, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 30 October 2008.

September 9, 2014

Military Camels/Baby Camels: Science & Domesticity

By Maria A. Windell (Guest Contributor)

By Maria A. Windell (Guest Contributor)

In May 1856, Captain David Dixon Porter, Major Henry Wayne, and the Supply dropped anchor of the coast of Indianola, Texas, and unloaded thirty-four camels to the care of the United States Army. Thus began the Army’s “Camel Corps” experiment. The experiment, however, was a short-lived and ill-fated one. While the camels adapted remarkably well to the climate and terrain of the US Southwest, US soldiers and horses proved ill-suited camel handlers and companions.

Although the “Camel Corps” experiment failed, and failed fairly quickly, a lot of consideration and support had gone into the decision to bring camels to the United States. On his travels Major Wayne was charged with consulting camel experts in England, France, and Tuscany, and the Report of the Secretary of War, produced for the Senate in 1857, includes extensive excerpts from several scientific and military texts on camels. For all of the Army’s scientific interest in the camels, though, some of the strangest and most amusing commentary on the camels focuses on the births of baby camels. This commentary highlights both cultural differences surrounding mother-child relationships and the degree of anthropomorphization that the camel births prompted. The appearance of baby camels, it seems, led military men straight into domestic discourse.

Six calves were born at sea as the Supply made its way from Turkey to the United States. Captain Porter allowed the Turkish caretakers who shipped with the Supply to handle the births of the first calves—to his great dismay. Porter blames the calves’ deaths upon “the Turkish mode of doing business,” which is to wrap the calf in a blanket immediately after its birth. The mother, he writes, subsequently “takes but little notice of her progeny; it is probable that she does not recognize it so wrapped up in a bundle of colored rags, or, if she does, is so disappointed with its appearance that she does not care about owning it.” When Porter and “the Bedouin” take charge of the next birth, and forgo swaddling the calf, the mother “testifie[s] much affection for it, not being shocked by the sight of the unsightly clothes by which the others had been so disguised, that the mothers did not recognize them as their own offspring.” Nineteenth-century Anglo-American domesticity creates certain expectations regarding affection, recognition, and mother-child bonding—and these expectations dictate Porter’s preferred camel birthing method. While Porter elsewhere praises the Turkish caretakers as “good, honest men . . . of a high[] order of intellect,” his assumption that the camels cannot recognize—or simply disown—blanket-wrapped calves is clearly based in part on his own dislike of those “colored rags.”

The fascination with baby camels extended well beyond the expedition. For instance, Harper’s Weekly, a popular newspaper, might have discussed any number of issues related to the camel experiment and “native” US camels. The Army tried to frame its interest in camels in scientific and military terms. But as various comments about baby camels show, images of domesticity and motherhood were just as important to the ways in which US Americans understood these “exotic” animals.

Maria A. Windell is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She works on nineteenth-century US literature in transnational context.

Image Citation:

Report of the Secretary of War, Communicating, in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate of February 2, 1857, Information Respecting the Purchase of Camels for the Purposes of Military Transportation. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

September 7, 2014

Hippocrates – and watercress?

by Helen King and Jo Brown

Taking the name of Hippocrates in vain… It happens all the time. When you work on any historical topic it inevitably involves some moments of screaming at the TV set. History programmes are popular viewing, and history is always being mentioned in other documentaries even when it’s not very relevant to the main argument.

The internet Hippocrates?

We’ve been doing some work on how the name of ‘Hippocrates’ is still being used to sell products – alternative medicine, weird diets, and now … watercress. Sometimes this involves picking a phrase from one of the 70 or so treatises associated with the Greek doctor Hippocrates; who, despite the casual name-dropping by those trying to cash in on his fame, probably wrote none of the texts of what we call the ‘Hippocratic corpus’. Then that phrase is taken out of context, and becomes almost a mantra. Examples would be ‘Let food be thy medicine’ (probably an elaboration of an extremely unclear ‘Hippocratic’ phrase), ‘first do no harm’ and ‘nature is the best physician’ (probably derives from a phrase in Epidemics VI). Just put any of these phrases into Google search or Twitter, and see what appears.

The watercress claims

So there was a certain amount of screaming at a recent episode of Channel 4’s “Food Unwrapped”. For those of you from outside the UK, this TV series ‘travels the world to uncover the truth about the food we eat’.

This episode included a feature on the health benefits of watercress. Dr Steve Rothwell, owner of ‘Vitacress’, is asked by the presenter about why he thinks watercress is so good. He responds:

“People have known about it for a long time. Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, when he built the world’s first hospital, he built it by a fast-flowing stream because he wanted to grow watercress which he deemed essential to the care of his patients. And it’s really the last sort of hundred years, that we’ve valued the taste and texture of eating watercress.”

Now Dr Rothwell may know a lot about growing watercress, but as historians we went into shock at the number of myths about Hippocrates being repeated here! Hippocrates as not just ‘father of medicine’ – a relatively old title – but father of modern medicine? Hippocrates as having built the world’s first hospital? Claims about the location of this (imaginary!) hospital? And finally, Hippocratic endorsement of watercress?

The myth of this first hospital next to a watercress bed is surprisingly ubiquitous. All over the internet, as sites copy other sites, it turns up in much the same wording as that used by Rothwell, for instance here or here or here…

Sometimes the myth includes a date – Hippocrates did this ‘in 400 BC’, an attempt, perhaps, to anchor the myth in an accessible chronology, to a date with a clear round number. However, for someone about whom so little is known, the use of so exact a date is nothing but misleading.

What do we mean by watercress?

Watercress is nasturtium officinale; it is native to Europe and to Asia. Some websites will tell you that the Greek for watercress is ‘kardamon’ (κάρδαμον); but this is not certain.

Kardamon isn’t watercress, but garden cress, the Latin lepidum sativum. Within the texts associated with the name of Hippocrates, garden cress seeds feature almost exclusively in the Hippocratic gynecological treatises, where they are part of a softening remedy for the mouth of the uterus, and are used to expel the fetus.

In one of the rare uses outside the gynecological texts, in the treatise On Ulcers the leaves of ‘narrow-leaved kardamon’ are used to fill an ulcer. Perhaps the ancient Greeks called both plants kardamon, but even if we include all the kardamon references we still don’t find anything that matches the internet myths.

Food for soldiers or food for failures?

Another story about it that circulates on the internet is that ‘The ancient Greek general, and the Persian king Xerxes ordered their soldiers to eat Watercress to keep them healthy’ What’s the evidence for this? Revealingly, some sites introduce the Xerxes story with ‘folklore has it that…’ But we can do a bit better than this. ‘The’ ancient Greek general here is named on other sites as Xenophon. The reference (which none of the sites gives) is actually to Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus 1.2.8.

But the story is nothing to do with soldiers! Instead, it is about Persian ways of bringing up children so that they will learn self-restraint: “Furthermore, they bring from home bread for their food, cress for a relish, and for drinking, if any one is thirsty, a cup to draw water from the river.” Further on, at 1.2.11, cress is described as food for failures: “Those of this age have for relish the game that they kill; if they fail to kill any, then cresses”.

Common to all these internet references seems to be one assumption: that if an ancient precedent can be found for the use of a plant, this is proof of the plant’s efficacy in medicine. After all, Dr Rothwell’s comments about Hippocrates’ approval of watercress were in answer to a question about the plant’s qualities, not about its history. And it seems unlikely that he would take up Hippocratic injunctions to chop up cress leaves and put them on to a skin ulcer.

Internet myths about Hippocrates and watercress won’t be affected by anything we’ve said here. Myths take on lives of their own. Maybe the only thing we can all agree on is that watercress is peppery-tasting, and nice in salads, or as a garnish for chicken!

Mrs Beeton’s chicken with watercress

September 3, 2014

Cleopatra’s Makeup

By Michelle Moran (Guest Contributor)

We tend to think of cosmetics as feminine perks of the modern life. Women treasure their favorite lipstick colors like gold, protect their skin with anti-aging creams, and spend countless hours in front of the mirror getting their eyeliner just right.

It surprises many people to know that ancient Egyptian women were just as fanatical about their cosmetics. Take a look at the portraits of ancient Egypt and you would be hard-pressed to find a woman (or a man) whose eyes aren’t perfectly lined with kohl, whose lips aren’t perfectly painted with ochre, or whose long tresses aren’t protected from the harsh desert sun by wigs.

A wealthy woman’s typical beauty regiment might begin with her waking in the morning and applying incense pellets to her underarms as a form of deodorant. Then, she might sit herself in front of a “mirror” (which was really polished bronze), and call for her servant to bring applets and grinders necessary for applying her daily makeup. Once the pallet was brought, she would watch her servant mix malachite with an oil derived from animal fat to create a eye-shadow. She would close her eyes as her servant applied the green power with sweeps of a small ivory stick carved on one end to look like the goddess Hathor. Then, when the eye-shadow was finished, the lady of the house would sit perfectly still while her servant lined her eyes with black kohl.

While these applications resulted in the beautification of the wearer, they had practical purposes as well. When applied above and beneath the eye, kohl served to protect the eyes from the intense glare of the sun. In fact, the Egyptian word for makeup palette appears to have been taken from their word to protect, which may reference kohl’s usefulness outdoors, or may even refer to the belief that outlining the eyes protected the wearer from the dreaded Evil Eye.

Once the lady of the house had on her protective kohl, she might then decide to use red ochre on her lips or dab her wrists and breasts with perfume. Having completed all of this, the lady would then dress for the occasion.

Michelle Moran is author of The Heretic Queen: A Novel">The Heretic Queen, Nefertiti, and Cleopatra's Daughter: A Novel">Cleopatra’s Daughter.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 28 January 2009.

September 2, 2014

George Washington’s New York

By Ted Steinberg (Guest Contributor)

By Ted Steinberg (Guest Contributor)

Where He Slept, Where He Stepped

There has been quite a fuss over where George Washington slept. But it’s where he stepped that matters more.

Consider New York where Washington was inaugurated in 1789. The Founding Father made the journey to the city in a stagecoach, was then barged across the harbor and dropped off at Murray’s Wharf, now the foot of Wall Street. When he stepped ashore he encountered an island that bore little resemblance to the looming towers, asphalt and steel found there today, but one that also had changed considerably since Henry Hudson came calling in 1609.

Washington ventured into a Lower Manhattan still dominated by marshland, a vast expanse of cordgrass and salt hay, marsh wrens and crabs. He entered a sweeping terra infirma, a city, yes, but one hemmed in on the north by a soggy frontier that stretched across the island. It is hard to imagine today with all the dense streets and monumental buildings looking as solid as a rock, but during high tide the water in the marsh complex may have briefly cut Lower Manhattan off from the rest of the island.

Canal Street

These days Canal Street is jammed with vendors selling everything from glass bongs to knock-off handbags. But the street was named for a reason.

As this map from 1775 shows, a ditch, beginning slightly above and to the right of the map’s center, had been built through the meadows to the Hudson River, a channel that declined over time into a stinking river of filth that was paved over and given the name it retains to this day.

And yet, when Washington stepped foot on the island he found himself not just in a water world subject to the tides but a place that was striving to beef itself up at the expense of the sea. Washington disembarked onto “made land,” that is, an area that had once been open water or marsh but had since been turned into solid ground to make way for the wharves that underwrote New York’s rise to dominance as a port.

Between the 1600s and Washington’s day, Manhattan had grown in size by seventy-four acres, as sandy beach and sloping shore gave way to a new bustling waterfront. The English colonists showed that land was not a fixed resource, a radical idea that laid the groundwork for one of the most engineered environments on earth, a Manhattan Island that is a stunning seventeen hundred football fields larger today than in Hudson’s time.

Ted Steinberg has worked as a U.S. historian for more than twenty years. His new book is titled Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. The book examines the ecological changes that have made New York the city that it is today.

Ted Steinberg has worked as a U.S. historian for more than twenty years. His new book is titled Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. The book examines the ecological changes that have made New York the city that it is today.