Holly Tucker's Blog, page 52

July 27, 2014

Books We Love

Archival Detectives

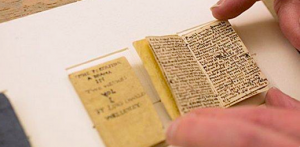

Archives play a major role for all of us at Wonders & Marvels. Whether we’re sitting in the hushed reading rooms at the Wellcome Library or wandering the gardens and museums at the Huntington, physical repositories are magical places. There we can play detective, hunting hard and in the right places to find historical figures, find details that help them breathe again, and locate flashes of what life was like before our own times. (For example, the archives show us that Samuel Pepys wrote his diary in code to keep privacy – see left.)

Digital archives are pretty exciting too! By this we don’t only mean tools like the Folger Library’s LUNA or Early English Books Online. We also mean collections like the one hosted right here. The closer W&M gets to its 1000th post (this is post 942 in case you were wondering), the more we’re looking back into the archives to understand this community’s past and future. Why does “What the Romans Used for Toilet Paper” keep drawing you back even after five years? And will “On Faking Virginity” soon be taking the mantle as the new “Most Viewed” piece?

Spies!

The W&M archives also hold up a mirror to our obsessions. One trend is certainly clear: Spies abound! While Kristie Macrakis recently uncovered a Nazi spy who hid secret ink in his teeth, Dara Horn examined the complex identity politics surrounding a Jewish spy living in the Confederate South. With an eye to the East, Pamela Toler educated us about the secrets surrounding Chinese silk worms (and exposed the methods by which spies and smugglers committed industrial espionage). We’ve even hosted the work of young scholars such as Marco Tiburcio, whose coursework on cryptography led to a piece on decoding Pigpen Cipher.

The fact that these posts only scratch the surface of the collection is telling. W&M‘s staff and writers are fascinated by spies. And, apparently, so are our readers.

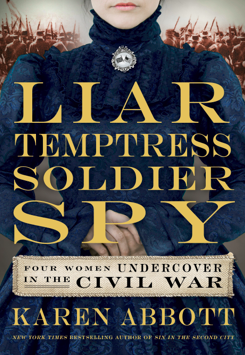

This self-awareness makes it even more logical that our first Books We Love feature is all about female espionage. There are clearly reasons that we’ve fallen in love with the four women of Karen Abbott’s Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy, and why we’ll even admit to trying out some of the techniques they used to write secret messages or smuggle important dispatches.

For all the reasons listed above, we’re willing to bet you want in on the secrets too (obviously we have a lot in common!). We’re only too happy to oblige by giving you the password that opens the door.

Books We Love: Features & Giveaways

From now until Wednesday, July 29 (11:00pm EST), those readers who sign up below for the W&M weekly newsletter “Secrets &  Spies: A Peek into Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy” will qualify for an Invisible Ink Pen Giveaway. Your subscription will also give you entree into the exciting and dangerous world of these female Civil War spies. Each week, Abbott will be revealing new information on spy-craft, she’ll be introducing you to her spies’ private lives, and she’ll be looping you in to some big giveaways leading up to her book release. She’ll also be discussing her upcoming special features at W&M: Dossiers of the Spies of LTSS (July 29 and August 5).

Spies: A Peek into Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy” will qualify for an Invisible Ink Pen Giveaway. Your subscription will also give you entree into the exciting and dangerous world of these female Civil War spies. Each week, Abbott will be revealing new information on spy-craft, she’ll be introducing you to her spies’ private lives, and she’ll be looping you in to some big giveaways leading up to her book release. She’ll also be discussing her upcoming special features at W&M: Dossiers of the Spies of LTSS (July 29 and August 5).

We hope you’ll join in!

Subscribe to Our Features

* indicates required

Email Address *

First Name

Weekly Feature: Liar Temptress Soldier Spy

Wonders & Marvels Monthly

July 26, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. viii

War and Peace were the major preoccupations filling our Cabinet of Curiosities this week.

War and Peace were the major preoccupations filling our Cabinet of Curiosities this week.

Our very own Karen Abbott joined the Travel Channel’s Monumental Mysteries to talk about Belle Boyd — a female Confederate spy who initiated her career by shooting a Union soldier who entered her home.

Abbott wasn’t alone in examining historical women at war. Matthew Ward shared amazing pictures of female lab workers testing chemicals in WWI – images that remind us of the drastically shifting gender dynamics that can result from international conflict.

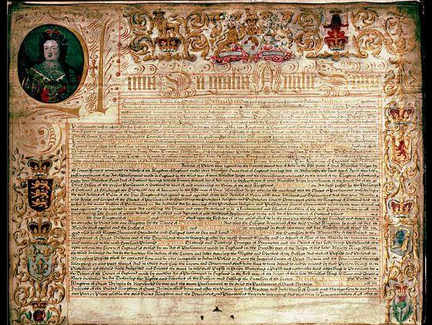

This week in history also marked the anniversary of the Treaty of the Union, which brought England and Scotland together as Great Britain (1706-08)–a relationship fraught with complexity.

Over at Archeology, scholars discussed the early hunting, gathering, and domestic economic conditions of 25,000 years ago. Their information is drawn from flint tools discovered in the Spanish Ametzigaina site.

How did Renaissance readers experience and interpret history? A new web project invites you to find out, revealing the marginalia that Gabriel Harvey left behind in his library’s historical and political texts.

Join us next week for more on our fascinations — and be sure to share your own here in the Comments or out on Twitter!

Can’t get enough Wonders&Marvels? Subscribe to our newsletter to get Features and Giveaways straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

July 24, 2014

One Knock for Yes, Two for No

By Saundra Mitchell (Guest Contributor)

Mrs. Fish and the Misses Fox: the original mediums of the mysterious noises at Rochester Western, N.Y.

It’s too simple to say that Spiritualism was popular in the 19th century because it was an excuse to behave badly, but it was certainly born from bad behavior.

It was 1848, in Hydesville, New York when the Fox Sisters started “hearing” strange rappings at night. Their house had a reputation for being haunted, and teens Kate and Margaret went along – asking spirits questions, which were answered by knocks and pops. Furniture moved, and the girls had fits they attributed to Mr. Splithoof, the devil.

This could have been a new Salem – Ann Putnam Jr. and Mercy Lewis’ accusations started out much the same way in 1692. But America had changed in the intervening century and a half. Puritanism had been replaced with Evangelicalism – and this time, it wasn’t unopposed.

In 1692, the initial, fervent explanation for the girls’ behavior was witchcraft. But in 1848, medicine understood that typhus was a disease, not a wasting due to too much night air. Messages could be carried spectrally, but scientifically, across telegraph wires. Science crashed against religion, and people wanted to reconcile both.

So when ghosts started knocking in Hydesville, and religion alone couldn’t answer, scientific method stepped in. What was the weight of a soul? You could put the dying on a scale, or you could ask the spirits themselves.

Thus began a movement that swept the western world from the 1840s to the 1920s – sparked by a moment of youthful rebellion. Kate and Margaret Fox were bouncing an apple on the floor when they were supposed to be in bed.

When caught, they told their mother the sound must have been spirits…and she believed.

Saundra Mitchell is the author of The Vespertine, a young adult novel set in Baltimore, 1889 at the height of the Spiritualism craze. She is an Edgar and Pushcart nominee, and a big fan of girls behaving badly.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 1 September 2011.

Giveaway is closed.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

July 22, 2014

Mending the Scars of World War I

by Jack El-Hai (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

With copper, foil, and paint, a little-known American sculptor saved scores of World War I soldiers from a faceless future.

A facially mutilated French soldier without his mask…

…and with it.

In the final months of 1917, groups of wounded soldiers began arriving at an artist’s studio on Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in the Latin Quarter of Paris. Moving haltingly and sometimes guided by helpers, they entered a courtyard filled with statues, climbed five flights, and found themselves in a large room illuminated by tall windows and banks of skylights. Their host was an imposing American with high cheekbones and pinned-back hair, a 39-year-old Bostonian named Anna Coleman Ladd.

As the men laughed and smoked, Ladd examined them. She studied their shot-off jaws, missing noses, and scarred and empty eye sockets. Doctors could not restore these soldiers to handsomeness, or even to ordinariness. But as a sculptor, Ladd could apply talents that the doctors lacked. She could make new faces—masks—for the men, beautifully crafting them of copper, metallic foil, and paint. And wearing their prosthetic masks, the soldiers could return to the families, fiancées, and friends they had been afraid to allow in their unsightly presence.

The volunteer work of this intrepid artist has vanished from our memory of World War I. During the year and a half she spent directing the work of the Red Cross Studio for Portrait Masks—a division of the French Bureau for Reeducation of the Mutilated—Ladd saved nearly 100 French soldiers, as well as several of other nationalities and civilians, from the deep isolation of disfigurement.

Conceiving the prosthetic mask

Some months earlier, Francis Derwent Wood, an artist initially assigned to wash dishes in a London hospital, noticed the distress of facially mutilated British soldiers and decided to do something about it. He developed a technique of packing facial wounds with cotton wool, creating a plaster mask that fit the soldier’s skin, and then building a clay model of a healed face. Wood took a cast of the clay model and, using an electrotyping process, deposited on it a thin layer of silver. In the end, he had a lightweight and well-fitting metal mask that, when skillfully painted and attached with a ribbon or spectacles earpieces, hid the ugly wounds of battle and offered a more presentable face.

Not long after, Ladd made the Atlantic crossing herself. By November 1917 she had patrolled the front line hospitals for suitable patients and opened her own portrait mask studio in Paris. She intended to improve on Wood’s technique. Using photographs of the soldier taken before his injury, or working from verbal descriptions if no photo was available, she sculpted a close duplication of the man’s undamaged features on a plaster cast. From that, she produced a mask of gutta-percha, a natural latex collected from evergreen trees. Hanging this mask in a copper bath infused with electric current resulted in the creation of a thin, light, metallic mask that she painted with an enamel concoction of her own invention to match the soldier’s skin tone. “If the wounded man was blind, the mask would be equipped with artificial eyes,” Ladd told a reporter years later. “Eyelashes, eyebrows, and even mustaches were affixed in the masks. They were light and durable. The masks will last a lifetime.”

Masks restored hope

In 1932 the French government belatedly paid tribute to her war work by making her a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor—an award she received only because a French diplomat admired one of her sculptures on exhibit in Italy and decided to research her career. None of her masks seems to have survived to the present day; some may have been buried with their owners, and Ladd apparently destroyed others. Her modesty about her war work probably contributed to the quickness with which her accomplishments disappeared from memory. When she died in 1939 in Montecito, Calif., the public knew her as a minor sculptor if they knew her at all, but a handful of French soldiers realized that they owed her their happiness.

Further reading:

Alexander, Caroline. “Faces of War.” Smithsonian, February 2007.

Biernoff, Suzannah. “The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain.” Social History of Medicine, November 25, 2011.

Romm, Sharon and Judith Zacher. “Anna Coleman Ladd: Maker of Masks for the Facially Mutilated.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 70, July 1982.

(This post was previously published in different form in The History Channel Magazine.)

July 21, 2014

The Celestial Sphere

By Sylvia Sumira (Guest Contributor)

Celestial and Terrestrial Globes

Celestial and Terrestrial Globes

When one thinks of a globe, what usually comes to mind is a sphere showing the earth. But in the past, celestial globes were just as important as terrestrial ones. In fact, celestial globes, that is, those showing the visible stars, pre-dated terrestrial globes. Though the ancient Greeks postulated that the earth was a sphere as long ago as the sixth century BC, the first record of a globe being made refers to a celestial sphere made by Eudoxus of Cnidus in the fourth century BC.

Early Globes and the Farnese Atlas

The earliest surviving globe dates from around 150 AD and is known as the Farnese Atlas. It is a carved marble celestial globe which depicts the figure of Atlas carrying the sphere of the Heavens on his shoulders. Constellations were devised as an aid to remembering and pin-pointing the positions of the stars. We still use the constellations formed in ancient times. Forty-eight classical Greek constellations were recognized by Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90-168 AD) whose main works, the Geographia, a description of the known world, and the Almagest, a treatise on astronomy, became vital reference works for the creative thinkers in late 15th and 16th century Europe. This was also the time when exploration of the world took off and as sailors from Europe travelled ever farther south, they saw stars which are not visible from northern latitudes. Astronomers compiled new star catalogues from observations by sailors and new constellations were invented, many of which survive today. For example, Crux (the Southern Cross) was first described by Amerigo Vespucci (after whom America was named) in 1503. Other constellations came and went: Renne (the Reindeer) was formed in 1736 by the astronomer Pierre Charles Lemonnier and appeared briefly on globes, but did not survive for long. If one looks closely at the southern hemisphere of celestial globes made after 1760, nestled in amongst the older constellations of animals and birds, one can see Microscopium (the Microscope), Telescopium (the Telescope), and other instruments and tools of the Age of the Enlightenment, all invented by the French astronomer Nicolas de Lacaille after cataloguing the southern stars in the 1750s.

So, the pattern of stars in the sky may be constant but how we organize them into constellations has evolved over time. Now there are eighty-eight ‘official’ constellations – at least for the time being.

Sylvia Sumira is an independent conservator specializing in printed globes. She worked in globe conservation at the National

Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London for several years and spent a period of study at the Austrian National Library in Vienna before setting up her own studio. She carries out work for museums, libraries and private clients. Her book

‘Globes – 4oo Years of Exploration, Navigation and Power’

has recently been published by the University of Chicago Press.

Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London for several years and spent a period of study at the Austrian National Library in Vienna before setting up her own studio. She carries out work for museums, libraries and private clients. Her book

‘Globes – 4oo Years of Exploration, Navigation and Power’

has recently been published by the University of Chicago Press.

Wonders & Marvels is thrilled to be able to give away three (3) copies of Sylvia Sumira’s GLOBES! To enter, please subscribe to our Book Giveaways here!“Book Club” subscribers will also receive updates on all upcoming giveaways.

The entry period ends 11:59pm EST on July 31.

(Currently, we can only ship to winners in the US)

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our newsletter below!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

var err_style = '';

try{

err_style = mc_custom_error_style;

} catch(e){

err_style = '#mc_embed_signup input.mce_inline_error{border-color:#6B0505;} #mc_embed_signup div.mce_inline_error{margin: 0 0 1em 0; padding: 5px 10px; background-color:#6B0505; font-weight: bold; z-index: 1; color:#fff;}';

}

var head= document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var style= document.createElement('style');

style.type= 'text/css';

if (style.styleSheet) {

style.styleSheet.cssText = err_style;

} else {

style.appendChild(document.createTextNode(err_style));

}

head.appendChild(style);

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

var mce_preload_checks = 0;

function mce_preload_check(){

if (mce_preload_checks>40) return;

mce_preload_checks++;

try {

var jqueryLoaded=jQuery;

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.type = 'text/javascript';

script.src = 'http://downloads.mailchimp.com/js/jqu...

head.appendChild(script);

try {

var validatorLoaded=jQuery("#fake-form").validate({});

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

mce_init_form();

}

function mce_init_form(){

jQuery(document).ready( function($) {

var options = { errorClass: 'mce_inline_error', errorElement: 'div', onkeyup: function(){}, onfocusout:function(){}, onblur:function(){} };

var mce_validator = $("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").validate(options);

$("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").unbind('submit');//remove the validator so we can get into beforeSubmit on the ajaxform, which then calls the validator

options = { url: 'http://wondersandmarvels.us6.list-man...?', type: 'GET', dataType: 'json', contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

beforeSubmit: function(){

$('#mce_tmp_error_msg').remove();

$('.datefield','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var txt = 'filled';

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

var bday = false;

if (fields.length == 2){

bday = true;

fields[2] = {'value':1970};//trick birthdays into having years

}

if ( fields[0].value=='MM' && fields[1].value=='DD' && (fields[2].value=='YYYY' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else if ( fields[0].value=='' && fields[1].value=='' && (fields[2].value=='' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else {

if (/\[day\]/.test(fields[0].name)){

this.value = fields[1].value+'/'+fields[0].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

} else {

this.value = fields[0].value+'/'+fields[1].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

}

}

});

});

$('.phonefield-us','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

if ( fields[0].value.length != 3 || fields[1].value.length!=3 || fields[2].value.length!=4 ){

this.value = '';

} else {

this.value = 'filled';

}

});

});

return mce_validator.form();

},

success: mce_success_cb

};

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').ajaxForm(options);

});

}

function mce_success_cb(resp){

$('#mce-success-response').hide();

$('#mce-error-response').hide();

if (resp.result=="success"){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(resp.msg);

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').each(function(){

this.reset();

});

} else {

var index = -1;

var msg;

try {

var parts = resp.msg.split(' - ',2);

if (parts[1]==undefined){

msg = resp.msg;

} else {

i = parseInt(parts[0]);

if (i.toString() == parts[0]){

index = parts[0];

msg = parts[1];

} else {

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

}

} catch(e){

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

try{

if (index== -1){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

} else {

err_id = 'mce_tmp_error_msg';

html = '

'+msg+'

';

var input_id = '#mc_embed_signup';

var f = $(input_id);

if (ftypes[index]=='address'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-addr1';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else if (ftypes[index]=='date'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-month';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else {

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index];

f = $().parent(input_id).get(0);

}

if (f){

$(f).append(html);

$(input_id).focus();

} else {

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

} catch(e){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

}

// ]]>

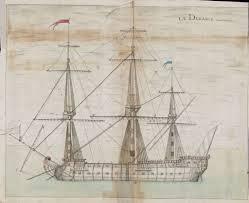

Travelers and Insects

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

By Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

By mid-July, it is possible to take a hike in the mountains of New England without being attacked by swarms of biting insects. As I enjoy my new freedom to stroll around outside even at dusk without having first covered myself with nasty repellents or having to constantly wave my hands rhythmically in front of my face like windshield wipers, I think of some of the travel accounts I have been reading, of 17th-century European voyagers to Louisiana.

Adventures of Choice

My current favorite is a recently discovered memoir by Marc-Antoine Caillot, a clerk for the French Company of the Indies, who made the Atlantic crossing in 1729. He had no experience of ocean voyages, and his memoir describes in lively detail the harrowing experiences that were routine for trans-Atlantic mariners and their passengers: storms at sea, depletion of water and food supplies, seasickness and disease from malnutrition, injuries, encounters with pirate ships, a rebellious crew and a sadistic captain. When his ship the Durance finally reached the Fort of Balize on an island off the Gulf Coast, Caillot and his fellow passengers, suffering from malnutrition and dehydration, were delirious with joy. The captain arranged for fresh water to be brought to the ship which, Caillot writes, was “like the best of wines.” He couldn’t wait to go to shore.

The Problems with Land

Once onshore, though, and after having relieved his hunger with a filling meal of beans and cornmeal, Caillot and some companions, who were being hosted by a plantation owner on the banks of the Mississippi, were ready to collapse into a welcome sleep on solid land. Apparently, up to that point, they had not noticed or been overly pestered by the insect population. “When it was time to go to bed,” he writes, “the only bed we had was a bearskin stretched out on the floor to cover ourselves with in order to protect ourselves from gnats and mosquitoes. In spite of how much I wanted to sleep, it was impossible for me to do so, because of those insects that were devouring us. There were so many of them that we were smashing them on our faces by the fistful.”

After a few hours of this, Caillot was ready to return to the sea. He borrowed a small boat from his host and headed back out onto the water. Inevitably, he had to continue on his voyage to New Orleans, but he never lost his the wary skepticism of life in the New World that began with his first night among the insects. Once arrived, he attempts in his memoir to faithfully catalogue and illustrate all the new experiences he encounters, including a scientific description of unfamiliar animals and insects.

But in the description of the biting insects, he gets carried away, and has to rein himself in: “As far as insects go, there are great numbers of them, especially mosquitoes, which they call maringouins. Thre are also gnats that are extremely small, and you get covered with them, even in your mouth, eyes, and nose. They bite as fiercely as the maringouin, … I will not speak about a number of other crawling and flying beasts for fear of trying the reader’s patience …”

For further reading: Marc-Antoine Caillot, A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies. New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2013.

July 19, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. vii

How quickly is July flying by? Here we are, another week ending and another rich collection tumbling out of our Cabinet of Curiosities. Among our latest findings, we even discovered some personal connections…

How quickly is July flying by? Here we are, another week ending and another rich collection tumbling out of our Cabinet of Curiosities. Among our latest findings, we even discovered some personal connections…

It’s amazing how the personal quirks of long-gone authors can enliven them for us. When Bibliophilia shared these archival images of 13 year old Charlotte Brontë’s tiny journals (containing adventure stories), it happened to us yet again. (This was a favorite of managing editor Miranda Nesler, who herself hoards tiny notebooks).

This week in history, Charles II of England chartered the Royal Society — a group dedicated to natural philosophy and scientific advancement. (Want to learn more about them? Our editor-in-chief Holly Tucker provided an in-depth look at the group in her book Blood Work).

In a conversation made possible in part by the Royal Society, Carl Zimmer reminded us about the science of blood types and the historical explorations (successes and failures) that led to now-common transfusions.

Invested in archives? (We are – they’re the spaces that make possible the work of our Regular and Guest Contributors!) Now start up company Rap Genius is too, and it raised over $40 million to expand beyond the documenting of rap lyrics and into literature and history materials. By preserving historical records and allowing crowd-sourcing that enables their continued life, the company hopes to emphasize that “Any text can be as layered, as allusive and cryptic, as worthy of careful exegesis as rap lyrics.”

What sparked your interest this week?

Tell us in the Comments or catch us on Twitter!

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our newsletter to get W&M features and giveaways sent straight to your inbox!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

July 16, 2014

When the Only Safe Sex was with Vampires

By Karen Essex (Guest Contributor)

[image error]When answering questions about my novel, Dracula in Love, I am inevitably asked about the sequences that readers find the most chilling and frightening – the scenes in the Victorian insane asylum. Surely those shocking scenarios, like the fantasy scenes of vampirism, are products of the author’s perverse imagination? Ironically, the answer is no; the asylum sequences are based on painstaking research. Truth, as it turns out, is always is stranger than fiction.

Dracula in Love retells Bram Stoker’s original story from the perspective of the vampire’s muse, Mina Harker, and in the process, turns the story on its ear, freeing Mina from her role as “victim,” and putting her at the center of her own story. A good deal of Stoker’s book takes place in an asylum. I wanted to utilize that Gothic setting in my book, but I also wanted to paint the asylum as it actually would have been at the time – full of women incarcerated for having what we today would consider normal sexual and other desires.

In the course of my research, I quickly discovered that women in the 1890s had more to fear from their own culture than from vampires. I read the psychiatric journals of the period, which prescribed bizarre treatments for ladies who were “hysterical,” which usually turned out to mean that they were “excitable in the presence of men.” In many instances, the desire to read all day or engage in intellectual studies, were also regarded as symptoms of mental illness in the female. Young women were committed to asylums for doing cartwheels in mixed company, for desiring sex with someone other than one’s husband, or for staring seductively at a man. Most behavior that showed spunk, spirit, or sexual need, was pathologized.

All sorts of harrowing and torturous cures were developed to “settle” these women – restraints, forced housework (to help them remember their true natures), repeated plunges in ice water, and force-feeding, to name a few. As mental illness in females was thought to originate in the womb, doctors also were obsessed with menstrual cycles, figuring that if a patient’s cycle could be regulated to a strict 28-30 day cycle, the “illness” of wanting to have sex or read books all day, would disappear. Not coincidentally, an irregular cycle was also considered a sign of mental illness and required treatment.

Curious as to whether these “cures” were actually implemented, I visited the archives of Victorian mental hospitals and read physicians’ reports from the late 1800s, often in the doctors’ own handwriting. Reading of young women committed for losing interest in housework, for lying about sexual encounters, or in one case, of a fifteen year old girl diagnosed with hysteria because she refused to stick her tongue out for the doctor’s tongue depressor, was heartbreaking.

Worse yet were the treatments, which often involved restraints to “pacify” the women. Women’s “fluttering, nervous hands” were thought to be a sign of hysteria, and the proscribed treatment was confinement – cuffs, muffs, straps, and strait jackets. Psychiatrists figured that if they could only calm the woman’s hands long enough, the patient would be soothed, hence, cured. More often than not, after prolonged periods of restraint, women’s spirits were entirely broken, at which point, they were allowed to return home. One of the most amusing anecdotes I ran across was the euphemism of “camisole” for the strait jacket because wearing it soothed a lady’s nerves in the same way that putting on a lovely garment might.

Think about that next time you slip into a bustier!

Though the Victorian era had its charms and pleasures – and I do explore those as well in Dracula in Love – it was a dangerous time to be a woman. If I were living in that era, I would surely have been committed. And I’m guessing that if you are reading this, you might have been my cellmate.

Karen Essex is the best-selling author of Dracula in Love, Leonardo’s Swans, Stealing Athena, and two acclaimed biographical novels, Kleopatra and Pharaoh. She lives and works in London and Los Angeles. To learn more about Karen’s work, please visit her website: www.karenessex.com.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 September 2011.

Searching for the Ghost of Edgar Allen Poe

By Stephanie Cowell (Regular Contributor)

He died in poverty and was found in clothes not his own. He was only forty years old. Two years before, he had lost his wife/cousin whom he had married when she was thirteen. 164 years after his death, we are still searching for him.

He died in poverty and was found in clothes not his own. He was only forty years old. Two years before, he had lost his wife/cousin whom he had married when she was thirteen. 164 years after his death, we are still searching for him.

Discovering the Man

In 2013, New York City’s Morgan Library featured an exhibition devoted to Poe’s work. It includes a piece of his corroded coffin, old newspapers with his stories in such tiny print one wonders anyone could see in those days (how did they set type so small?). His writing is hardly bigger, written on small pieces of paper glued together, and, in one case, on a scroll. There are only a few photographs and drawings. He made a living as a journalist. People loved the macabre then as today, and he supplied stories. His was a great intellectual mind and he died too soon. One wonders that his work survived above all the other journalists turning out poems and stories for the many newspapers in the dirty, crowded streets of New York in the 1830s and 1840s.

I read Annabel Lee written in his handwriting. It was supremely moving.

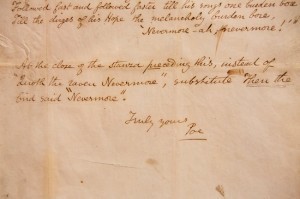

Poe’s instruction to his publisher revising The Raven

Ghost Hunting

But why should I not search for him? He lived four blocks from me on a street renamed for him; there was also a café called Edgar’s where I would drink coffee with friends (this café is unfortunately closed.) Of course his house there is gone, swept away a long time ago, perhaps before they began to turn New York’s Upper West Side from farmland to middle-class housing.

Then on a misty October evening (it was truly!) I was invited to attend a Poe ghost walk, given by the Ghosts of New York Walking Tours in conjunction with my friend the novelist Lynn Cullen, whose novel Mrs. Poe appropriately debuted in October. A small group of us gathered in front of 116 Waverly Place in the heart of Greenwich Village. In 1845, Poe walked up those steep steps to a literary gathering to first read his poem The Raven. I looked at the steps and then down the street over the cars to the bright lights of a coffee shop. How New York has changed! The new owner of the old house says she has sometimes heard footsteps on the wood floor above her. But there is no one there.

After learning about the house, we walked through Washington Square Park with the street lamps glimmering through the trees. The area has been a graveyard, the guide told us, and the bones of twenty thousand people lay beneath our feet. That gave me pause for thought. It was already a public park when Poe lived nearby, but the fountain which was possessed by guitar-playing hippies in the 1960s and the famous Arch were not yet created.

As she explained all this, a brooding man in his thirties with strange genius in his eyes seemed to walk under the trees and disappear. But then, all my friends know that I feel ghosts.

______________________

Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 29 October 2013.

July 15, 2014

A Life Bound to Three Revolutions

By François Ferstenberg (Guest Contributor)

Louis-Marie, Viscomte de Noailles, descended from one of France’s noblest families. His ancestors had served France’s kings for centuries. His great-great-grandfather was Henri II’s ambassador to England in the middle of the sixteenth century. His great-grandfather was a general under Louis XIV, the Sun King. His mother was Marie-Antoinette’s first lady of honor.

When the American Revolution broke out, Noailles was eager to prove himself. In October 1781, at the battle of Yorktown, he repelled a desperate British sortie, leading a company of his Soissonois Brigade with the shout “Vive le roi!” When the British called for a truce, it was Noailles who represented the French government in the negotiations for Lord Cornwallis’s surrender.

After the war Noailles returned to France, where he threw himself into politics and liberal reform. When the French Revolution erupted in 1789, Noailles served in the Assemblée constituante, which drafted the first constitution in French history. He became a leading liberal voice. It was he who presided over the assembly on August 4, 1789, when feudal privileges were abolished.

But as the French Revolution grew more radical, Noailles fled France to the United States. He lived in Philadelphia for several years, cavorting with the great and good in the American capital. He became a merchant and rebuilt a fortune. These were momentous years in French and American history, and his was a momentous life.

But for sheer drama, nothing matched his final days.

A Momentous Life and a Dramatic End

When Napoleon determined to re-establish a French empire in North America in 1802, Noailles sailed to the Caribbean to join the mission. He was stationed in Saint Domingue, today’s Haiti, where since 1793 the island’s hundreds of thousands of slaves had liberated themselves; there he conducted a quasi-independent foreign policy under the leadership of the brilliant Toussaint Louverture.

Noailles was one of the last French officers to abandon the island in the waning days of the horrific French mission, just days before Haiti declared its independence. Late one December evening of 1803, he evacuated his garrison and the French inhabitants they’d been protecting. Sailing at night, he eluded the British ships patrolling the Caribbean waters and landed on the coast of Cuba.

But Noailles had not finished fighting. Dropping off the French inhabitants and most of his soldiers, he outfitted a privateerand sailed it back out. As the evening set on December 31, 1803, Noailles encountered the Hazard, a British privateer. He raised a British flag and approached, addressing the captain—after nearly a decade in the United States, Noailles’ English was excellent.

He learned that the Hazard was patrolling the waterways between Cuba and Haiti on the lookout for a general named Noailles who had recently managed to elude the British navy. What a coincidence! Noailles exclaimed. He was on the same mission. Why not join forces?

Later, under the cover of night, he sprang his audacious trap. Ramming the Hazard from the side, he stormed the deck at the head of thirty grenadiers and surprised its crew. After a fierce battle they captured their prize, and Noailles, although wounded, sailed into Havana victorious. The scene was commemorated in a grand historic portrait by Théodore Gudin, the French painter, commissioned by Noailles’ son, now in the possession of one of his descendants. (How I acquired an image of portrait is another story.)

Noailles died a few days later from his wounds. His soldiers enclosed his heart in a silver box, draped with regimental colors, and sent it back to France, where it was buried.

François Furstenberg, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, is the author of When the United States Spoke French: Five Refugees who Shaped a Nation, which follows the adventures of several aristocratic émigrés who lived in the United States in the 1790s.

Wonders & Marvels has five (5) copies of François Ferstenberg’s WHEN THE UNITED STATES SPOKE FRENCH for an exciting July giveaway!

Simply subscribe to our monthly giveaway list here!

“Book Club” subscribers will also receive updates on all upcoming giveaways.

Wonders & Marvels has five (5) copies of François Ferstenberg’s WHEN THE UNITED STATES SPOKE FRENCH for an exciting July giveaway!

Simply subscribe to our monthly giveaway list here!

“Book Club” subscribers will also receive updates on all upcoming giveaways.

The entry period will end 11:59pm EST on July 31. (Currently we can only ship in the US)

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our newsletter below!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

Image: Louis-Marie, Vicomte de Noailles, painted byGilbert Stuart, 1798. Metropolitan Museum of Art.