Holly Tucker's Blog, page 55

June 20, 2014

Editor’s Corner: Favorite Stories

In last week’s Editor’s Corner column, I encouraged everyone to send along questions about researching and writing about history—or about writing life in general.

In last week’s Editor’s Corner column, I encouraged everyone to send along questions about researching and writing about history—or about writing life in general.

Keep them coming please! It’s easy: just leave a comment here or drop me an email.

Here’s the deal: If I pick your question, I’ll hand select a special book just for you from the overflowing Wonders & Marvels bookshelves or, if you prefer, a send along a signed copy of my last book.

So this week’s question comes from Ephraim P:

“What’s your favorite research-related travel story?”

While researching my last book, I traveled often to specialized library collections abroad and walked the streets of Paris and London to retrace the steps of my seventeenth-century doctors, patients, and killers.

Most often, my strolls were an exercise of trying to imagine the past–rather than actually walking in it. Life and time move on. Physical spaces get repurposed, demolished, rebuilt. And to my great disappointment, Louis XIV will never greet me at the gates of Versailles. (More on that crazy fantasy here!)

This was not the case at the Hôtel Montmor, the private residence where the main “character” of Blood Work did his horrific animal-to-human blood transfusion experiments.

I remember waiting for what seemed like hours one beautiful May day for someone to exit the soaring wood doors of the impressive compound on the Rue du Temple just so I could steal a peek at what lay behind. Once I finally gained access, I stood in the cour d’honneur, mouth agape and eyes watering. I was joyous…and overwhelmed.

Everything was precisely as I had imagined it after having worked so long with period maps, architectural plans, and descriptions in manuscript letters. The concierge of the building, Jean-Marie Carpentier, approached me cautiously, likely wondering if I were not a bit like the mentally-ill man that Baptiste used as one of his first transfusion patients.

Everything was precisely as I had imagined it after having worked so long with period maps, architectural plans, and descriptions in manuscript letters. The concierge of the building, Jean-Marie Carpentier, approached me cautiously, likely wondering if I were not a bit like the mentally-ill man that Baptiste used as one of his first transfusion patients.

As I explained in French (thanks to my French Grandmother, from whom I learned the language), the words came tumbling out in near gasps. Up there, that’s where Montmor’s private scientific Academy met. This is the staircase Denis walked up on the night of his history-making experiment. Under these dormers there is where Mauroy stayed after the transfusion.

After Monsieur Carpentier confirmed to my delight that the staircase, the balustrade, the tiles, all of it was in its original state, we spent the rest of the afternoon together exploring the building and what is left of the gardens–teaching each other about its rich history. As we strolled among the ghosts, I was reminded once again of how insanely grateful I am to get to the type of research I do as a researcher, teacher, and writer.

So what close encounters with the past have you had? Drop a line or leave a comment!

June 18, 2014

The Kangaroo’s Tale: How an errant elevator door ended an odd form of popular entertainment

By Jack El-Hai (W&M Contributor)

When an elevator door slammed shut at the Minneapolis Auditorium on March 20, 1940, an era of American entertainment came to a bloody end. The door crushed the six-foot-long tail of Peter the Great, a famed boxing kangaroo, who was touring the U.S. and had just demonstrated his skills to a Minneapolis audience.

Peter’s owners and managers, Mr. and Mrs. Ted Elder, considered the injury minor and wrapped the marsupial’s tail with a bandage. They began driving Peter to his next engagement in Omaha, but it became obvious along the way that the kangaroo was in distress. The Elders rushed Peter back to the O.B. Morgan Dog and Cat Hospital in Minneapolis, and they were about to have the damaged body part amputated when the 160-pound kangaroo died.

Peter, a singularly famous boxing kangaroo, had made a notable impression on American popular culture. Less than a year before, he fought a boxing match with “Two Ton” Tony Galento, a pugilist who had once floored Joe Louis. During an exchange of blows, Peter dropped back on his tail and kicked Galento in the groin. The man-versus-beast match ended in a draw. A wave of publicity carried Peter to shows around the country.

If Peter had lived, he would have played a role in U.S. electoral politics. He was scheduled to appear with comedienne Gracie Allen and serve as the mascot for her 1940 mock run for the Presidency. Without Peter’s help, Allen’s Surprise Party never found traction, and Franklin Roosevelt won the 1940 election without a satirical opponent.

In a lawsuit they filed against the city of Minneapolis, the Elders claimed that Peter’s boxing and entertainment talents resulted from his special training. “Peter the Great,” Mrs. Elder testified, “was no ordinary kangaroo.” The city countered that swinging and kicking when threatened is instinctive behavior for his species. A jury sided with the city, and Peter’s owners did not receive the $75,000 they sought in compensation for their loss.

No other kangaroo rose to Peter’s level of fame after his death. As exploitations of stage animals began to smell of cruelty, boxing kangaroos disappeared except as cartoonish symbols of Australian resilience. Today we never encounter them in the flesh. Peter the Great’s fame and profession belong to the past.

Sources:

“Jury Refuses Damages for Death of Kangaroo.” Milwaukee Journal, October 8, 1940.

“Peter, Boxing Kangaroo, Dies.” The New York Times, March 24, 1940.

Zahn, Thomas R. The Minneapolis Auditorium and Convention Center: The History. 1987.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and his Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness and the forthcoming book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist. He often writes about medicine and history.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 6 August 2012.

Mrs. Margaret Bryan, Astronomer of Blackheath

By Lucy Inglis (Regular Contributor)

It is a common misconception that during the Georgian period all girls were either not educated or were given a substantially different education than male children. This was, in some cases, true; but there were also tutors and academies all over the country, and particularly in London, which sought to give girls significant scientific and mathematical knowledge. Margaret Bryan’s schools are an excellent example.

It is a common misconception that during the Georgian period all girls were either not educated or were given a substantially different education than male children. This was, in some cases, true; but there were also tutors and academies all over the country, and particularly in London, which sought to give girls significant scientific and mathematical knowledge. Margaret Bryan’s schools are an excellent example.

Mrs Margaret Bryan was born, it is thought, some time before 1760. She had two daughters and was married to Mr. Bryan. In her thirties, she opened a school for girls near Hyde Park Corner. But Margaret Bryan’s school had one remarkable difference from its contemporaries: it was an academy for teaching girls mathematics and science.

In 1795, she moved the academy to Blackheath, where it flourished until 1806. In 1797 she published A Compendious System of Astronomy. In it, she excuses her temerity in writing on such subjects, explaining that the text was for the use of her students rather than for public consumption. Her friends, she said, insisted she publish, and she asked to be judged by those who like her, sought ‘truth, although enfeebled by female attire.’

Charles Hutton, Professor of Mathematics at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, endorsed the work of the ‘beautiful’ Mrs. Bryan, saying that, ‘even the learned and more difficult sciences are … beginning to be successfully cultivated by the extraordinary and elegant talents of the female writers of the present day.’ Hutton respected Bryan and encouraged her in her 1806 Lectures of Natural Philosophy: thirteen lectures on hydrostatics, optics, pneumatics and acoustics.

Her final publication came in 1815, with An Astronomical and Geographical Class Book for Schools. In 1816, she left for Margate, where instead of retiring, she opened another academy.

June 17, 2014

Meet Miranda Nesler: Managing Editor Q&A

As I mentioned in my first Editor’s Corner—and as you’ve likely noticed around the site—lots of changes at Wonders & Marvels!

As I mentioned in my first Editor’s Corner—and as you’ve likely noticed around the site—lots of changes at Wonders & Marvels!

I thought you might enjoy getting to know our new Managing editor, Miranda Nesler, who joined the team officially in May. Previously, Miranda was a guest contributor, and her posts include Silence and the Scold’s Bridle, Charles I and the Act of Dying, and Women Speaking from the Archives.

Holly Tucker: Hi, Miranda! So glad to have you on W&M, and excited to have a chance to chat with you. We’ve known each other for a long time, ever since you were studying at Vanderbilt University, but it’s good that the readers will get a chance to know you too. Why don’t you tell them a little about yourself?

Miranda Nesler: Sure, I’d be happy to. I earned my PhD in literature at Vanderbilt, with specialties in early modern gender, animal studies, material culture, and textual studies. For a number of years I taught in these fields and had contact with a number of talented students—at Vanderbilt and later at Ball State University—before making a career shift. Because archival research, writing, and editing really have my heart, I decided to take them up full time by freelancing and joining W&M.

HT: What is it that drew you to those fields?

MN: Honestly, the tensions and discomforts that are such a huge part of them. I was fascinated initially by the tensions that existed in early modern drama— between the play as a bodily action on stage as well as a written text, for example. This led to an interest in women, who during the period existed at the center of questions about performance but were so often prevented from public speech or participation in debates since they were considered “half-human.” Because so much of women’s experience wasn’t recorded in canonical “literature,” archival digging for their personal writings and then taking an experiential approach to material culture were key ways of accessing them. I could read a diary entry about being strapped into a busk or learning target archery at a country house, and then I could do it myself to gain a deeper understanding.

Archery Practice

HT: And those interests were part of the reason I thought you would fit here since our writers and readers are all fascinated by historical curiosities. Could you tell us a little bit about what you love about archives?

MN: There are so many things! Libraries and museums give you close, multi-dimensional contact with the historical figures you’re working with. You not only get to see their portraits or examine their clothing, but you even get to read their journals, learn their handwriting, or figure out their reading interests until you think you know them inside and out. Sometimes you even find a document, like a letter, a marginal note in a book, or someone else’s journal entry about that person, that shocks you by adding new dimension and reminding you just how real and how dynamic these people’s communities were. My love of queens Anna and Henrietta Maria were born out of the archives—I found them because I was working on men’s drama and they kept getting peripheral mention. After working with them more and more, I feel like they’re friends and collaborators in my work.

HT: I know I’ve had similar experiences, especially when I was writing Blood Work and now as I’m finishing this next one. You get attached because you start to realize that these people are complicated, not just “good” or “bad.” So now I have to ask my favorite question: If you could spend one day in the past, which day would it be and why?

MN: I knew this one was coming! February 2, 1609: the only performance of Anna’s Masque of Queenes. These masque performances were one-offs, huge preparation and expenditure put into one night; it’s part of why women were able to do them. Because the women were using their costumes, their bodies, the sound of their shoes to make noise in a space where they were barred from speech, you lose so much if you’re limited to the text. I’d love to see Anna and her ladies appear in Whitehall Palace dressed as Amazons and warriors, shocking the audience and “defending” the king from witches!

Miranda Garno Nesler is the Managing Editor at Wonders & Marvels. She is also a freelance writer, researcher, and editor who is working in collaboration with The James Shirley Project and oversees the animal studies blog Performing Humanity. In her spare time, you can find her with her overly affectionate labrador Poe, doing target practice at the archery range, curating her extensive shoe collection, or on Twitter @PerformHumanity.

June 16, 2014

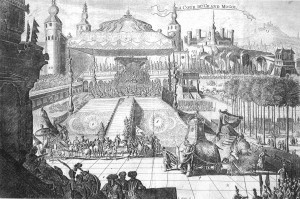

From Hannibal to ‘Game of Thrones’: Elephants, Travel, and Power

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (Regular Contributor)

In the attack on The Wall of the North in Game of Thrones, giants ride on the backs of mastodons, striking terror in the hearts of the Sworn Brothers of the Knights Watch.

The Attack on the Wall of the North

Ever since the Roman Empire, western travelers to distant lands have been fascinated by elephants and attracted by their power. Elephants were an outsized, intelligent, living force that could be harnessed to serve the ambitions of men. The Carthaganian commander Hannibal’s voyage over the Pyrenees and the Alps with an army accompanied by elephants became a tale that stuck in the imagination of every schoolchild. And European travelers to Asia in the first waves of exploration for trade and the expansion of political power wrote letters home that were full of descriptions and illustrations of these marvelous animals.

Hannibal and his war elephants crossing the alps

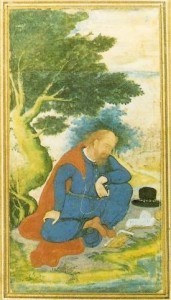

One of these was a French physician and man of science named François Bernier. In 1665, he accompanied the Mughal Prince Aurangzeb and his court on a long trek into the beautiful and remote valley of Kashmir. Bernier prided himself on cool, objective reporting of everything he observed. But when it came to elephants, he was lyrical. Elephants carried large, curtained structures on their backs, transporting the ladies of the court, which added to the mystery and intrigue that Bernier associated with the sight of them. But on this voyage, as Bernier wrote, the spectacle turned to tragedy: “A strange accident cast a gloom over these scenes and dampened all our pleasure. The King was ascending the highest of all the mountains, followed by a long line of elephants, upon which sat the ladies … The first elephant, appalled, we suppose, by the great length and steepness of the path before him, stepped back upon the elephant that was moving in his track, who again pushed agaisnt the third elephant, the third against the fourth, and so on until fifteen of them, incapable of turning round or extricating themselves in a road so steep and narrow, fell down the precipice. Happily for the women, the place where they fell was of no great height; only three or four were killed; but there were no means of saving any of the elephants. Whenever these animals fall under the tremendous burden placed on their backs, they never rise again even on a good road. Two days afterward we passed that way, and I observed that some of the poor elephants still moved their trunks…”

For Bernier, the loss of the elephants was more traumatic and touching than the loss of the people they were transporting. Bernier’s travel narratives may have influenced his friend La Fontaine, writer of animal fables, who argued that animals, like humans, are possessed of a soul. Other readers would respond to his elephant story as a morality tale, warning against the excesses and inevitable fall that follows human pride.

Seventeenth-Century “portrait of a French doctor,” possibly François Bernier

For further reading:

Francois Bernier’s description of a voyage to Kashmir in Beyond the Three Seas: Travellers’ Tales of Mughal India. Random House, 2007.

The Court of the Great Mughal, illustration from François Bernier’s Travels

June 13, 2014

Cabinet of Curiosities, vol. ii

Welcome back to Cabinet of Curiosities, our round-up of the history related news and happenings that we’ve “dug up” over the past week!

Welcome back to Cabinet of Curiosities, our round-up of the history related news and happenings that we’ve “dug up” over the past week!

As parts of the US — and the world — experience drought and clean water shortage, news this week is that Earth may be holding out on us. After years of searching, scientists have discovered an underground reservoir that contains immense amounts of water in addition to clues on the planet’s formation.

Also found underground? Bones that may be the remains of Olaf, the Viking King of Ireland.

Following their 2012 discovery, the bones of King Richard III of England, which were unearthed from a car-park, have fascinated literary scholars, historians, and scientists alike. They now will find their final resting place Leicester.

Above ground, too, the World Cup is exciting football fans across national boundaries. The Wall Street Journal explores the tournament’s recent history, and the rivalries that shape it.

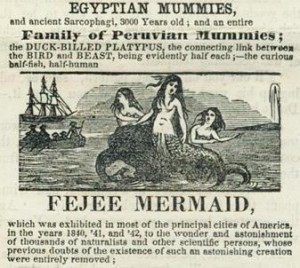

And before signing off, we’ll head underwater and say hello to the Feejee Mermaid–one of Barnum & Bailey’s greatest hoaxes.

What news have you excavated this week? Share with us in the comments section or on Twitter @history_geek!

And, if you want to stay up to date on happenings around W&M, subscribe to our email list!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

var err_style = '';

try{

err_style = mc_custom_error_style;

} catch(e){

err_style = '#mc_embed_signup input.mce_inline_error{border-color:#6B0505;} #mc_embed_signup div.mce_inline_error{margin: 0 0 1em 0; padding: 5px 10px; background-color:#6B0505; font-weight: bold; z-index: 1; color:#fff;}';

}

var head= document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var style= document.createElement('style');

style.type= 'text/css';

if (style.styleSheet) {

style.styleSheet.cssText = err_style;

} else {

style.appendChild(document.createTextNode(err_style));

}

head.appendChild(style);

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

var mce_preload_checks = 0;

function mce_preload_check(){

if (mce_preload_checks>40) return;

mce_preload_checks++;

try {

var jqueryLoaded=jQuery;

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.type = 'text/javascript';

script.src = 'http://downloads.mailchimp.com/js/jqu...

head.appendChild(script);

try {

var validatorLoaded=jQuery("#fake-form").validate({});

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

mce_init_form();

}

function mce_init_form(){

jQuery(document).ready( function($) {

var options = { errorClass: 'mce_inline_error', errorElement: 'div', onkeyup: function(){}, onfocusout:function(){}, onblur:function(){} };

var mce_validator = $("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").validate(options);

$("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").unbind('submit');//remove the validator so we can get into beforeSubmit on the ajaxform, which then calls the validator

options = { url: 'http://wondersandmarvels.us6.list-man...?', type: 'GET', dataType: 'json', contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

beforeSubmit: function(){

$('#mce_tmp_error_msg').remove();

$('.datefield','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var txt = 'filled';

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

var bday = false;

if (fields.length == 2){

bday = true;

fields[2] = {'value':1970};//trick birthdays into having years

}

if ( fields[0].value=='MM' && fields[1].value=='DD' && (fields[2].value=='YYYY' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else if ( fields[0].value=='' && fields[1].value=='' && (fields[2].value=='' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else {

if (/\[day\]/.test(fields[0].name)){

this.value = fields[1].value+'/'+fields[0].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

} else {

this.value = fields[0].value+'/'+fields[1].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

}

}

});

});

$('.phonefield-us','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

if ( fields[0].value.length != 3 || fields[1].value.length!=3 || fields[2].value.length!=4 ){

this.value = '';

} else {

this.value = 'filled';

}

});

});

return mce_validator.form();

},

success: mce_success_cb

};

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').ajaxForm(options);

});

}

function mce_success_cb(resp){

$('#mce-success-response').hide();

$('#mce-error-response').hide();

if (resp.result=="success"){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(resp.msg);

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').each(function(){

this.reset();

});

} else {

var index = -1;

var msg;

try {

var parts = resp.msg.split(' - ',2);

if (parts[1]==undefined){

msg = resp.msg;

} else {

i = parseInt(parts[0]);

if (i.toString() == parts[0]){

index = parts[0];

msg = parts[1];

} else {

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

}

} catch(e){

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

try{

if (index== -1){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

} else {

err_id = 'mce_tmp_error_msg';

html = '

'+msg+'

';

var input_id = '#mc_embed_signup';

var f = $(input_id);

if (ftypes[index]=='address'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-addr1';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else if (ftypes[index]=='date'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-month';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else {

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index];

f = $().parent(input_id).get(0);

}

if (f){

$(f).append(html);

$(input_id).focus();

} else {

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

} catch(e){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

}

// ]]>

Cabinet of Curiosities

Welcome back to Cabinet of Curiosities, our round-up of the history related news and happenings that we’ve “dug up” over the past week!

Welcome back to Cabinet of Curiosities, our round-up of the history related news and happenings that we’ve “dug up” over the past week!

As parts of the US — and the world — experience drought and clean water shortage, news this week is that Earth may be holding out on us. After years of searching, scientists have discovered an underground reservoir that contains immense amounts of water in addition to clues on the planet’s formation.

Also found underground? Bones that may be the remains of Olaf, the Viking King of Ireland.

Following their 2012 discovery, the bones of King Richard III of England, which were unearthed from a car-park, have fascinated literary scholars, historians, and scientists alike. They now will find their final resting place Leicester.

Finally, above ground, the World Cup is exciting football fans across national boundaries. The Wall Street Journal explores the tournament’s recent history, and the rivalries that shape it.

What news have you excavated this week? Share with us in the comments section or on Twitter @history_geek!

And, if you want to stay up to date on happenings around W&M, subscribe to our email list!

Subscribe to our mailing list

* indicates required

Email Address *

How often would you like updates? (check one)

Monthly Digest

Weekly Digest

Posts as They Happen (2-3 times a week)

var err_style = '';

try{

err_style = mc_custom_error_style;

} catch(e){

err_style = '#mc_embed_signup input.mce_inline_error{border-color:#6B0505;} #mc_embed_signup div.mce_inline_error{margin: 0 0 1em 0; padding: 5px 10px; background-color:#6B0505; font-weight: bold; z-index: 1; color:#fff;}';

}

var head= document.getElementsByTagName('head')[0];

var style= document.createElement('style');

style.type= 'text/css';

if (style.styleSheet) {

style.styleSheet.cssText = err_style;

} else {

style.appendChild(document.createTextNode(err_style));

}

head.appendChild(style);

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

var mce_preload_checks = 0;

function mce_preload_check(){

if (mce_preload_checks>40) return;

mce_preload_checks++;

try {

var jqueryLoaded=jQuery;

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

var script = document.createElement('script');

script.type = 'text/javascript';

script.src = 'http://downloads.mailchimp.com/js/jqu...

head.appendChild(script);

try {

var validatorLoaded=jQuery("#fake-form").validate({});

} catch(err) {

setTimeout('mce_preload_check();', 250);

return;

}

mce_init_form();

}

function mce_init_form(){

jQuery(document).ready( function($) {

var options = { errorClass: 'mce_inline_error', errorElement: 'div', onkeyup: function(){}, onfocusout:function(){}, onblur:function(){} };

var mce_validator = $("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").validate(options);

$("#mc-embedded-subscribe-form").unbind('submit');//remove the validator so we can get into beforeSubmit on the ajaxform, which then calls the validator

options = { url: 'http://wondersandmarvels.us6.list-man...?', type: 'GET', dataType: 'json', contentType: "application/json; charset=utf-8",

beforeSubmit: function(){

$('#mce_tmp_error_msg').remove();

$('.datefield','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var txt = 'filled';

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

var bday = false;

if (fields.length == 2){

bday = true;

fields[2] = {'value':1970};//trick birthdays into having years

}

if ( fields[0].value=='MM' && fields[1].value=='DD' && (fields[2].value=='YYYY' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else if ( fields[0].value=='' && fields[1].value=='' && (fields[2].value=='' || (bday && fields[2].value==1970) ) ){

this.value = '';

} else {

if (/\[day\]/.test(fields[0].name)){

this.value = fields[1].value+'/'+fields[0].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

} else {

this.value = fields[0].value+'/'+fields[1].value+'/'+fields[2].value;

}

}

});

});

$('.phonefield-us','#mc_embed_signup').each(

function(){

var fields = new Array();

var i = 0;

$(':text', this).each(

function(){

fields[i] = this;

i++;

});

$(':hidden', this).each(

function(){

if ( fields[0].value.length != 3 || fields[1].value.length!=3 || fields[2].value.length!=4 ){

this.value = '';

} else {

this.value = 'filled';

}

});

});

return mce_validator.form();

},

success: mce_success_cb

};

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').ajaxForm(options);

});

}

function mce_success_cb(resp){

$('#mce-success-response').hide();

$('#mce-error-response').hide();

if (resp.result=="success"){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(resp.msg);

$('#mc-embedded-subscribe-form').each(function(){

this.reset();

});

} else {

var index = -1;

var msg;

try {

var parts = resp.msg.split(' - ',2);

if (parts[1]==undefined){

msg = resp.msg;

} else {

i = parseInt(parts[0]);

if (i.toString() == parts[0]){

index = parts[0];

msg = parts[1];

} else {

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

}

} catch(e){

index = -1;

msg = resp.msg;

}

try{

if (index== -1){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

} else {

err_id = 'mce_tmp_error_msg';

html = '

'+msg+'

';

var input_id = '#mc_embed_signup';

var f = $(input_id);

if (ftypes[index]=='address'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-addr1';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else if (ftypes[index]=='date'){

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index]+'-month';

f = $(input_id).parent().parent().get(0);

} else {

input_id = '#mce-'+fnames[index];

f = $().parent(input_id).get(0);

}

if (f){

$(f).append(html);

$(input_id).focus();

} else {

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

} catch(e){

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').show();

$('#mce-'+resp.result+'-response').html(msg);

}

}

}

// ]]>

Editor’s Corner: Place Matters

As a child, a tattered Rand McNally book of maps was all that I needed to entertain me on family road trips. I liked to track where we were heading, where we had been, and all of the places we had yet to be. I also marveled at how a simple turn of the map’s orientation brought new perspectives. Is there such a thing as reading a map upside down?

It all depends are where you think you are.

Maps have always been a huge part of my life as an academic and as a writer. I suspect that this comes from being a person who is deeply attached to notions of place and how place helps define culture.

Place Matters

I have lived in Nashville for over 17 years now—with several long stints in France interspersed between. There is something grounded, culturally, about the city. I know that I am somewhere when I am here. And this somewhere can be found nowhere else.

Where else but Nashville could I get expert advice from a neighbor about how to cook the dandelion greens in my CSA farm basket this week? Or chat with one of my favorite music artists—while we both volunteered at a school event? Or sip bourbon at a 19th century farmhouse, while listening to a friend who is an expert on the Battle of Franklin regale us with vivid stories in that lilting drawl of his?

Mapping Early Paris

I work a lot with maps as I write because they give me key insights into how the people I write about understood their relationship to place and space.

My “go to” map right now is the Turgot Map (1739). What I love about this map is that is more than just a representation of streets. You can actually get a sense of how people may have moved through the city and, even, invaluable details about what the buildings looked like.

Turgot Map

For both this book and Blood Work, I used the Turgot images alongside other period documents (paintings, municipal records, correspondence, tourist accounts of the city). The map is unusually accurate.

The maps provide me with clues about what the folks I write about would have seen, or heard, or smelled. Have a look at the Turgot map. Do you see the boats on the Seine? If I were writing about something that happened in that neighborhood, I would try to figure out what those boats might have been carrying, who were in them, and where they came from. While these details are not necessarily core to my narrative, they can provide visceral details that can help bring the past to life.

Brainstorm with Me

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this column—and am eager for any ideas you might have for future posts. Have any questions about research, writing, or publishing? I’ll do my best to answer them here!

Don’t hesitate to leave a comment or

send me an email!

Holly Tucker is Editor-in-Chief of Wonders & Marvels.

June 11, 2014

The Art of Beagling in Eighteenth-Century England

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

Snoopy, the world’s most famous beagle, epitomizes several of the breed’s traits: the dangly ears, the prominent snout, the fixation on food. But in the cartoon, he retreats regularly to an imaginary world of adventures to escape the monotony of a dog’s life. An eighteenth-century beagle’s life would, perhaps, have been of more interest to him—the confinement of kennel-life interspersed with the thrill of the hunt. Beagles became an established hunting breed in the fifteenth century and, by the early eighteenth century, there was much information on how to build the best beagle hunting pack.

An illustration of the Southern Hound. From J.H. Walsh, The dog, in health and disease, by Stonehenge (1859). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The breed that we know and (in my case) love today was very different in early modern England. The term beagle was used until the eighteenth century to describe several sorts of hounds, including the harrier.[1] The smallest of the hounds, beagles were used primarily for chasing hares and were known for their “exquisite smell” and perseverance.[2] By the eighteenth century, there were three main types of beagle, outlined in 1788 by Cynegetica or essays on sporting consisting of observations on hare hunting &c. The wire-haired Northern Beagle was small (about 12 inches), fast, impetuous and cheerful, doing “his business as furiously as Jehu himself can wish him”. The smooth-haired Southern Beagle was larger, rangier, phlegmatic, slower and patient. A third type of beagle was a small lapdog, which—according to The Sportsman’s Dictionary (vol. 1, 1705)—makes a pretty diversion in hunting the coney”, but was otherwise not serviceable.

Building “a neat Pack [was] somewhat difficult”, advised James Lambert in 1710 (The Countryman’s Treasure). Lambert specified that the hounds should be well-matched with each other or “one will hinder another”. Cynegetica and other books recommended that the owner breed the Northern and Southern types together, with the goal of producing offspring that would keep the tenacious scent-tracking of the Southern with a little of the Northern’s speed. The Sportsman’s Dictionary suggested that, when crossed, they would make “great killers”. Lambert added to this that there should be two “Hunts on the Highway” to follow scent on hard ground and “two old staunch Hounds” to moderate the “over-swiftness of the younger and unexperienced”.

The owner should also take care to match the pack to his own temperament; the slowness of the Southern Beagle, say, might prove “trifling and tedious” to a man who preferred speed (Cynegetica). Particular care should also be taken in the musicality of the pack, for as Ralph Beilby described, beagle “tones are soft and musical, and add greatly to the pleasures of the chase”. Lambert gave thought as to how the pack owner might achieve “better Harmony”: “some whiners and Treble-cryers are necessary”. A well-balanced pack of twenty beagles would be most efficient and provide the most pleasure in the hunt.

There was also much advice on the care of the pack, from conception to diet. The hunting dogs were, perhaps, afforded better care than many people in early modern society. Nicholas Cox wrote that the female should be strong and well-proportioned, while the sire should be young. An old sire would result in “dull and heavy whelps”. A pregnant female should be allowed free range of the house and fed hot broth daily (The huntsman, 1780). Suitable hound names, as listed by Cox, included noble titles (Younker, Countess, Cesar, Duke), flowers (Lily, Tulip), mythological (Daphne, Hector, Dido, Juno), sounds (Music, Ranter, Thunder, Tatler) or personality (Fuddle, Wanton, Plunder, Merry-boy, Jolly-boy)…

Around the age of one, a dog could be introduced to the pack and would benefit, at first, from “the smack of the whip” (The gentleman farrier, 1732). Lambert outlined the pack’s daily care routine. Kennels should be dry, warm and vermin-free, with a supply of clear water and daily sun. The dogs should also have access to a “chimney-fire in cold damp weather” where they could cool down after a hunt. This would prevent diseases like mange, itch and fever, which were thought to be caused by sudden changes in bodily temperature. Their food was to be given throughout the day and included broth with crusts, table scraps and whey and milk with bran.

There was an art to beagling, which entailed close attention to hound care, breeding and pack harmony. The descriptions of an ideal pack reflected wider social ideals of obedience, stability, mastery and efficiency, as well as highlighted the quality of life gap between the poor in society and their squires’ dogs. By 1800, Sydenham Edwards claimed that it was rare to see a full pack of beagles any more. Instead, the beagles were kept primarily as finders to greyhounds in coursing. As huntsmen turned their attention from hares to foxes, beagling fell out of fashion and, over the nineteenth century, a more modern beagle was born. But one thing remains constant, as Snoopy’s pursuit of the Red Baron shows: dogged perseverance.

[1] Sydenham Edwards, Cynographia Britannica (London, 1800).

[2] Ralph Beilby, A general history of quadrupeds (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1790).

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800), as well as teaches a course on “Defining Boundaries: Natural and Supernatural Worlds in Early Modern Europe”. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. Follow her on Twitter, where she tweets as @historybeagle.

This post was first released at Wonders & Marvels on 30 May 2013.

Civil War Mourning Customs

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

By Karen Abbott (Regular Contributor)

Nearly 700,000 men died in the Civil War, more from disease than from battlefield wounds (“bowels are of more consequence than brains” was a common jest”) and these fatalities ultimately belonged to those left behind; it was the survivors who had to contend with the business of burying and grieving. The scale of the carnage demanded a strict set of social rituals, a culture of mourning in which the literal embodiment of death was considered the best way to accept it.

For women this meant stocking their armoires with “mourning” fashion, which was more readily available in the North even though its death rate was one third of that of the Confederacy. In the spring of 1863, down on Ladies’ Mile, Lord & Taylor opened a “mourning store” where new widows could dress their grief fashionably, selecting from a variety of now-esoteric fabrics: Black Crape Grenadines, Black Balzerines, Black Baryadere Bareges, Black Bareges, Mourning Silks, Lawns, Chintzes, Alpacas, Barege

Shawls, and Grenadine Veils. Godey’s Lady’s Book, the mid-19th century’s answer to Vogue, regularly printed drawings of bonnets, collars, sleeves, breakfast caps and a variety of mourning dresses for all occasions.

Mourning attire evolved over a period of stages, growing progressively less stringent. “Deep” or “heavy” mourning required a widow to wear all black dress and accessories, including a heavy black crepe veil. Jewelry was verboten unless it was made of polished coal, a lock of hair of the deceased, or a small picture of the deceased. Next came full mourning, during which her black dress and veil could be accented by lighter shades of lace and cuffs. The final stage, half mourning, allowed shades of lavender and gray; Godey’s recommended a black silk and French grenadine ensemble topped off with a Leghorn hat, trimmed with black velvet and black plume.

Mourning attire evolved over a period of stages, growing progressively less stringent. “Deep” or “heavy” mourning required a widow to wear all black dress and accessories, including a heavy black crepe veil. Jewelry was verboten unless it was made of polished coal, a lock of hair of the deceased, or a small picture of the deceased. Next came full mourning, during which her black dress and veil could be accented by lighter shades of lace and cuffs. The final stage, half mourning, allowed shades of lavender and gray; Godey’s recommended a black silk and French grenadine ensemble topped off with a Leghorn hat, trimmed with black velvet and black plume.

For a widow, the entire public grieving process lasted a minimum of two and a half years, although after April 1865 Mary Todd Lincoln spent the rest of her days swaddled in black. She was too distraught to appear at her husband’s funeral but later recorded her grief in a private letter to a friend: “Time brings so little consolation to me and do you wonder when you remember whose loss. I mourn over that of my worshipped husband, in whose devoted love, I was so blessed, and from whom I was so cruelly torn. The hope of our reunion in a happier world than this, has alone supported me, during the last four weary years.” When she died in Springfield in 1882, her body was laid out in the parlor of her sister’s home—in the exact spot where, 40 years before, she had stood as a bride.

Karen Abbott is the author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose, both New York Times bestsellers. She is a featured contributor to Smithsonian magazine’s history blog, Past Imperfect, and also writes for Disunion, the acclaimed New York Times series about the Civil War. She’s at work on her next book, a true story of four Civil War spies who risked everything for their cause. Find her online at www.karenabbott.net or @KarenAbbott on twitter.

This post first appeared at Wonders & Marvels on 23 July 2012.

References:

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Dorothy Denneen Volo and James M. Volo. Daily Life in Civil War America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998.

“Sealed With Sorrow.” New York Times, September 9, 1999.

Images:

Young girl mourning her cavalry father (Library of Congress)

Woman in mourning dress and jewelry (Library of Congress)