Holly Tucker's Blog, page 59

March 15, 2014

Up yours, Brutus!

One of the first things that greeted visitors to the Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum exhibition at the British Museum in the summer of 2013 was a jolly fresco of a phoenix above two peacocks (below right). On the audio guide, curator Paul Roberts called this fresco a “pub sign”. It was found on a wall of a fast food joint in Pompeii. The slogan reads Phoenix felix et tu: “The Phoenix is happy (or ‘lucky’), and you!”

What caught my attention was the phrase “et tu” which immediately called to mind Julius Caesar’s last words (according to Shakespeare), “et tu, Brute”. Of course, as any Classicist knows, Caesar didn’t really say et tu. He spoke in Greek: Kai su, teknon, which means “and you, my child.” This is often interpreted as the poignant words of a noble, betrayed Roman to the young assassin who might have been his illegitimate child: “Even you, my son?”

But the phoenix pub sign hints that Caesar might not have gone down quite that submissively on the Ides of March in 44 BCE.

One thing the Pompeii exhibition brought home to me was how obsessed the ancient Romans were with keeping away evil. A little research showed me that the phrase “and you” – whether in Greek or Latin – is apotropaic.

Apotropaic is Greek for something that “turns away”. It usually refers to anything that averts evil or bad luck. Apotropaic images include the raised palm of the left hand, erect phalluses, the unflinching gaze of a full frontal face and the eye amulets that are still so popular in the Mediterranean. Also apotropaic is the peacock, which has a tail full of “eyes”. All these things “turn back evil”.

The phrase et tu (“and you”) has a similar meaning. It reflects back. Our modern equivalent might be “the same to you!”. In Roman times, if a person approached you with good intentions, saying “et tu” would be a blessing. But if they came at you with evil intent, the phrase becomes a curse. So whether Julius Caesar said et tu or kai su to the young man stabbing him, it meant the same thing: “Back at you, punk!” or better yet: “Up yours, Brutus!”

The phrase et tu (“and you”) has a similar meaning. It reflects back. Our modern equivalent might be “the same to you!”. In Roman times, if a person approached you with good intentions, saying “et tu” would be a blessing. But if they came at you with evil intent, the phrase becomes a curse. So whether Julius Caesar said et tu or kai su to the young man stabbing him, it meant the same thing: “Back at you, punk!” or better yet: “Up yours, Brutus!”

Caroline Lawrence writes history-mystery books for kids aged 8 – 80. You can find out more on her website www.carolinelawrence.com

March 11, 2014

Vincent Van Gogh’s Rehearsals

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (W&M Contributor)

Many of us have had the experience of visiting a museum and seeing one of the iconic paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, and thinking that we had seen it before in another museum. This is because Van Gogh did in fact make multiple versions of some of his paintings that have become the best known – such as the portraits of the postman Roulin and his family, his painting of his bedroom at Arles, and the portrait of a woman known as ‘L’Arlesienne’. The Phillips Collection in Washington recently organized a wonderful exhibition called Van Gogh: Repetitions, featuring some of these.

[image error]The practice of making a “repetition” of his own painting was, for Van Gogh as for many other painters since the Renaissance, a way of continuing to explore the possibilities of the original, as opposed to simply copying it. Repetitions always involve changes, and occasionally, as Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, he would come to like the repetition better than the original. An interesting point about the French word ‘répétition’ is that it also translates as ‘rehearsal’, a fact that was not mentioned in the exhibition material on view at the Phillips Gallery. In their letter correspondence, Vincent and his brother Theo certainly seem to have had this meaning of the word in mind. Returning to certain paintings over and over again, Van Gogh seemed to understand them as performances subject to repeated reworking.

In one letter to Theo written on September 5, 1889, when Vincent was suffering a particularly violent bout of the chronic illness that had led him to a sanitorium, he suggests that his practice of ‘repetitions’ was [image error]a form of therapy, a kind of rehearsal for what he hoped would lead to his cure. Describing a man whose portrait he was working on, he writes: “He’s a man of the people, and simpler. Anyway, you’ll see it if I succeed in it and if I do a repetition of it. I’m struggling with all my energy to master my work, telling myself that if I win this it will be the best lightning conductor for the illness.”

Another indication that Vincent and Theo both were thinking of this meaning of the word ‘répétition’ may be found in some letters from 1888. Theo Van Gogh was an art dealer, and in his letters to his brother he would report on his purchases. In January he wrote to Vincent that he had just purchased a painting by Degas, whose practice of returning repeatedly to the same subject in his paintings was one that both brothers found fascinating. The title of the painting, which showed a group of dancers preparing for a performance, was “La Répétition” – The Rehearsal.

March 10, 2014

Automata in history

By Helen King (W&M Monthly Contributor)

Do you ever feel your dining table needs cheering up?

This week I saw a collection of possibly the last word in ways to impress your dinner guests. I was at the wonderful Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna where the Kunstkammer – a selection from the amazing ‘cabinet of curiosities’ assembled by various rulers of the Habsburg Empire – includes a series of automata, mechanical devices that move apparently by themselves. These are elaborate, beautifully made pieces with various moving parts, and some of them play music while the little figures hit their drums and blow their trumpets. My favourite was probably the ship - which, like several of these automata, was created actually to move along the table in front of amazed guests, finally firing its tiny cannons (which looks to me like it would risk giving guests a heart attack, even if it didn’t set fire to their clothing!).

I’ve always been impressed by automata. But I can only begin to imagine the reaction of people in 1585 – no, that date isn’t a typo – when Hans Schlottheim’s ship first sailed across a table. While automata can be disturbing because they very explicitly upset the boundaries between animate and inanimate, living and dead, human and inhuman, would these early examples have been seen as clever artifice or would their viewers have been briefly fooled by what they saw? At a dinner held at a European court, guests would have expected to be amazed and perhaps would be waiting for the moment when their host brought out the latest expensive toy, or speculating as to whether any of the table decorations was about to spring into action. I wonder, though, what the servants would have made of all this? Would they have worried that they were witnessing witchcraft?

But these were certainly not the first automata in the European imagination. The craftsman god Hephaistos is described as making automata; in Homer’s Odyssey we read of gold and silver dogs created by him, which guarded the palace of King Alcinous. How did he do it? According to a description of another of Hephaistos’ automata, a bronze lion, he animated his creations by putting pharmaka in them. Pharmaka is the word used for ‘drugs’; perhaps here it means ‘powerful material’. Although these automata were probably just the product of Homer’s imagination, in the Hellenistic period scientists discussed how these plans could be realised through pulleys, levers, and hydraulic and pneumatic technologies, although scholars still disagree as to whether someone like the first-century AD Hero of Alexandria really made any of the objects he described in his treatise, Automata. What is clear, however, is that the treatise had an enormous influence in the Renaissance, when it prompted learned men to construct the objects described in it – and, in the process, to impress their patrons and their patrons’ guests!

If you’d like to know more:

Christopher Faraone, ‘Hephaestus the Magician and Near Eastern Parallels for Alcinous’ Watchdogs’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 28 (1987)

Minsoo Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines: The Automaton in the European Imagination (Harvard University Press, 2011) 257-280

March 8, 2014

A Plague of Locusts

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

In the second week of June 1873, a southwest wind carried a strange brown cloud over the border from Dakota Territory into Minnesota. Pioneer families initially mistook the cloud for a rain or dust storm. But as it filled the sky, they could see that it contained millions of tiny animated specks.

The fierce Rocky Mountain locust

The cloud obscured the sun, and suddenly an agrarian nightmare became real. Hordes of winged insects descended upon the fields, devouring virtually all crops and green plants.

Though commonly called grasshoppers, these fiercely hungry insects were Rocky Mountain locusts. They battled humans for control over the American Midwest during the mid-1870s. For five consecutive summers the locusts ravaged farmland, honeycombed the soil with eggs, and forced bewildered state governments to enact drastic and unprecedented measures. Then, even more mysteriously than they had appeared, the locusts vanished.

The Rocky Mountain locust normally lived in the eastern foothills of the Rockies, from Colorado to Canada. Periodic population explosions drove large numbers to seek food beyond their native range, and they took to the winds. Crossing the plains at speeds approaching 70 miles per hour, they reached Minnesota in the summer of 1873 eager to feast and breed.

And they reproduced prolifically, lacing the soil with pods containing up to 28 eggs each. During the next two years, the eggs hatched and the cycle continued. The year 1876 brought the most overwhelming attack of locusts in the recorded history of the Upper Midwest. That year the locusts were particularly voracious and aggressive. When feasting in a field, as a pioneer woman wrote, “the sound of their feeding could be heard yards away. Seldom did they leave a field until every stalk, leaf, and green head was consumed.” Throughout Minnesota, 28 counties reported serious damage.

A new governor, John Pillsbury, toured the state incognito to view the devastation first-hand. He was appalled. The insect invasion destroyed Minnesota’s wheat crop that summer, with only half of the previous year’s total harvested. More than a fifth of the state’s oats and corn went to the locusts, as well.

Desperate farmers tried their luck with the new products of inspired inventors. The Simpson Locust Crusher, a wooden contraption dragged by horses, scooped up and pulverized the insects. The Adams Locust Pan drowned them in oil. The Hopperdozer trapped them on metal sheets coated with coal tar or molasses. Governor Pillsbury also urged farmers to fight the locusts with “loud and discordant noises made by striking tin vessels, and by shrieking and yelling with the voice.”

By summer’s end, the locusts embedded their eggs into the earth of 42 Minnesota counties covering an enormous area. One farmer reckoned that his fields contained 150 eggs per square inch, or “the nice little pile of 6,586,272,000 on seven acres of my farm.” The signs pointed toward another ruinous year in 1877, which would sink the state’s economy. For the forthcoming growing season, the state legislature passed a law requiring all men between 21 and 60 to donate a day per week for five weeks for the collection and destruction of locusts and eggs.

Pillsbury, however, dealt with the threat of crisis in his own fashion. He declared April 26, 1877, a day of statewide prayer and fasting to invoke God’s prevention of the coming disaster. Although religious skeptics protested the governor’s faith in prayer, Pillsbury thought he had proved the skeptics wrong. “The very next night,” he later remembered, “it turned cold and froze every grasshopper in the state stiff — froze them solid.” His recollection was inaccurate. Though retarded by a late frost, the insects did hatch and damaged many sections of western Minnesota. But for unknown reasons the locusts took flight and vanished in July, without depositing any eggs. The bumper wheat crop of 1877 was the best in the state’s history.

One swarm of locusts did return to Otter Tail County, Minnesota, in 1888, and some insects appeared in North Dakota in 1900. The last was spotted in 1902 in Manitoba. After that, the Rocky Mountain locust never again bugged Minnesotans or anyone else. The species is now extinct.

Note: I previously wrote about the locust plague in May 1986 for Mpls.St.Paul magazine.

Further reading

Lockwood, Jeffrey A. Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect That Shaped the American Frontier. Basic Books, 2009.

Yoon, Carol Kaesuk. “Looking Back at the Days of the Locust.” The New York Times, April 23, 2002.

March 6, 2014

Rivers as Weapons in Ancient War

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Semiramis, queen of Assyria (seventh century BC) boasted in an inscription that she had extended her borders with courage and cunning: “I compelled rivers to run where I wanted, and I wanted them to run where it was advantageous.” Diverting rivers is an age-old environmental tactic in the history of war. According to Stratagems by Frontinus, a Roman commander and Manager of Aqueducts in Rome, Semiramis had conquered Babylon with a brilliant water trick. The Euphrates River flowed through Babylon, dividing the city in two. Semiramis ordered her engineers to divert the river, allowing her army to march in the dry river bed right into the heart of the city. The very same feat was attributed to the mythical sorceress Medea and to two historical conquerors of Babylon, the Persian king Cyrus and Alexander the Great.

A stream was diverted to literally flush out an enemy by the Roman commander Lucius Metellus, fighting in Spain in 143 BC. The Spanish army camped in an easily flooded plain alongside a stream. The Roman legionaries damned the stream and waited in ambush to slaughter the panicked Spaniards as they ran for high ground.

In 78-74 BC, Rome was embroiled in a difficult campaign in Isaura, a rugged region of eastern Turkey. The Isaurians were fiercely independent mountaineers labeled as “brigands and bandits” by the Romans. Publius Servilius finally defeated the fortified towns of Isauria by diverting the mountain streams where the Isaurians drew their water, “forcing them to surrender in consequence of thirst.”

Julius Caesar, in Gaul in 51 BC, used the same trick against the city of Cadurci. Because the town was surrounded by a river and many springs, his river-diversion plan required his troops to dig extensive networks of underground channels. Then Caesar stationed his archers to cut down the parched Gauls as they attempted to reach the river. The stratagem was successful: Cadurci surrendered.

Polyaenus, a Macedonian lawyer, wrote a military treatise for the Roman emperors Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius in AD 161. In it he claimed that the mythic hero Hercules had changed the course of a Greek river to destroy the Minyans because he was afraid to face such skilled cavalrymen in open battle. This story was intended to give the co-emperors a way to justify resorting to devious ruses instead of facing risky face-to-face battles, as they were preparing to enter a daunting war against the invincible Parthians of Central Asia. The Parthians, feared for their heavily armored cavalry and formidable horse archers, had just invaded the Eastern Empire—and, in fact, they were never defeated by the Romans.

Cunning tricks like diverting rivers to gain access to a city or to cause floods are examples of creative unconventional warfare. Unless such ploys killed entire populations by drowning (as occurred in some Islamic attacks by flooding towns in the early Middle Ages), diverting rivers aroused few moral qualms, because a well-prepared city or army should be able to anticipate or counter such tactics. But secretly poisoning water or food was another matter and raised ethical questions in most ancient societies.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 1, 2014

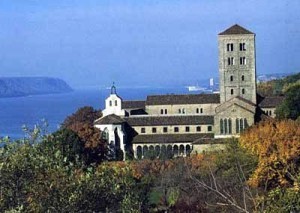

The Cloisters New York City: An enchanted medieval world

by Stephanie Cowell

If you are willing to take a long bus ride, you can catch the New York City bus to the Cloisters. It bumps along Fifth Avenue and then eventually turns north on upper Broadway. After a very long time, you turn into the enormous open gates of a park which sits high above the Hudson River. The bus rounds a corner, you look up at the great tower, and you are no longer anywhere but here, perhaps the year 1200, some place in France.

You have arrived at the Cloisters Museum.

It is not a real Cloister, or actually it is parts of several real cloisters, brought stone by stone from various abandoned monasteries in Europe and reassembled and connected with clever architecture in upper New York City. It is a place that has stayed much the same since I first entered it as an awestruck girl of thirteen. Even then somewhere inside of me the historical novelist was growing. I was looking for the Europe of centuries past and here it was. Some bit of medieval music was even wafting in the air, or perhaps I did not hear it until subsequent visits.

I have been there so often now during all seasons and over so many years that my visits have blended. The dreamy girl turned into the young mother; then I think I was not able to go for a time. My sons grew up, I began to write novels and returned and found it waiting for me.

The Hunt of the Unicorn

At my first visit, first I thought that the Cloisters had always been there but of course it has not. Like many great endeavors, it took a few visionaries and then hundreds of other gifted people from stoneworkers to curators to create it.

In 1917 the land which it crowns high above the bucolic Hudson River was purchased by the philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. who developed it into Ft. Tryon Park. He also bought parts of five European abbeys which were carefully disassembled, each stone marked to identify its proper place; they were reconstructed and integrated together in the park between 1934 and 1939 with additional buildings in medieval style designed by architect Charles Collens, assisted by Joseph Breck and James J. Rorimer. To begin the astonishing collection of medieval art, Rockefeller bought the huge collection of American sculptor George Gray Barnard. Rockefeller also donated from his own walls the world famous Unicorn tapestries. (Created in the 15th century, these remarkable tapestries were at one low point used to cover heaps of potatoes in France and then served as bed hangings.)

In 1958, a major new addition was added to the Cloisters Museum: a twelfth-century limestone apse from the church in Fuentidueña, Spain, also dismantled and reconstructed stone by stone.

For me it is a sacred rite to visit the Cloisters. When I enter the doors and climb the stairs, something inside me drifts into an awed silence. I feel it belongs to me but I know every other person there feels that as well, and that we share it.

Water plays from an old fountain; saints with stone faces worn dull watch us pass. In the Treasury, a space of a few small rooms, priceless illuminated prayer books which were used for prayer seven centuries ago look up at us; Crucifixes and reliquaries and tiny portable altars made of ivory small enough to fold into a pocket seem to listen for our steps. There is a very old staircase of wood and I am sure someone was about to descend as I came around the corner, someone who is not quite in this world anymore. It was after all the great scientist Einstein who wrote, “…the distinction between past, present, and future is only an illusion, however persistent.”

I like to sit in the Cuxa Cloister with my back to one of the columns. I always go down to the herbal gardens with their quince trees and the overlook of the park and the river. I love the intimate flowery Trie Cloister where a small café operates now in seasonable weather, and you can have a coffee and small sandwich. I always stop in the bookshop. I leave a little dreamy; I am never quite ready to re-enter the world.

I like to sit in the Cuxa Cloister with my back to one of the columns. I always go down to the herbal gardens with their quince trees and the overlook of the park and the river. I love the intimate flowery Trie Cloister where a small café operates now in seasonable weather, and you can have a coffee and small sandwich. I always stop in the bookshop. I leave a little dreamy; I am never quite ready to re-enter the world.

There is, after all, a spirit in the Cloisters Museum which is more than the sum of its parts. There is more to it than worn stone art, flowering trees, herbal gardens, hand-illuminated prayer books; it is the entrance to a place where the most reflective part of us meets a place beyond time. And especially if you live in the city, you can go there whenever you want and find that place inside yourself again. ____________________________

____________________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie is currently finishing two novels, one on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, and the second about the year Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

February 18, 2014

The Black Hole of Calcutta

by Pamela Toler

In mid-eighteenth century India, power was up for grabs. The Mughal dynasty was in decay. Smaller regional powers flourished. European trading companies, which held their trading privileges at the discretion of Indian rulers, were constantly looking for a way to get an edge. The British and French East India Companies, in particular, maintained private armies with which to defend themselves–usually against each other.

In mid-eighteenth century India, power was up for grabs. The Mughal dynasty was in decay. Smaller regional powers flourished. European trading companies, which held their trading privileges at the discretion of Indian rulers, were constantly looking for a way to get an edge. The British and French East India Companies, in particular, maintained private armies with which to defend themselves–usually against each other.

In 1756, the British East India Company became involved in a dispute with the new Nawab of Bengal, twenty-six-year-old Siraj-ud-duala. The young Nawab looked on the growth of the British settlement at Calcutta with both greed and suspicion. When he learned that the British merchants, in anticipation of war with France, had begun to expand their fortifications without his permission, he marched on Calcutta with 30,000 foot, 20,000 horse, 400 trained elephants and 80 cannon. The city was defended by a small, badly trained, force of soldiers and militia. Siraj-ud-daula attacked early on June 20.Anyone who could escaped down river by boat in a disorganized retreat. Those who had been unable to escape surrendered by mid-day and spent the night in the the Black Hole, a cell in which the British locked up drunken soldiers. The next day, the survivors were forced to leave Calcutta and made their way downriver to Fulta, where the rest of the Calcutta merchants had taken shelter.

The incident was made infamous by the account of one of the survivors, John Zephaniah Holwell. Published in 1758, Howell’s pamphlet, titled A Genuine Narration of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen and others who were suffocated in the Black Hole, was popular reading in the eighteenth century and frequently reprinted. Holwell reported that 146 English, including one woman, were held in an 18 square foot cell with one small barred window; only 21 survived the night. Referring to his experience as “a night of horrors I will not attempt to describe, as they bar all description,” he went on to describe the event in horrific detail. The story became part of the mythology of empire when Thomas Babington Macaulay borrowed heavily from Holwell for his own lurid account of the incident in his 1840 essay on Lord Clive.

The incident was made infamous by the account of one of the survivors, John Zephaniah Holwell. Published in 1758, Howell’s pamphlet, titled A Genuine Narration of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen and others who were suffocated in the Black Hole, was popular reading in the eighteenth century and frequently reprinted. Holwell reported that 146 English, including one woman, were held in an 18 square foot cell with one small barred window; only 21 survived the night. Referring to his experience as “a night of horrors I will not attempt to describe, as they bar all description,” he went on to describe the event in horrific detail. The story became part of the mythology of empire when Thomas Babington Macaulay borrowed heavily from Holwell for his own lurid account of the incident in his 1840 essay on Lord Clive.

There is no doubt that the men who attempted to defend Calcutta against Siraj-ud-daula, led by Howell himself, were incarcerated in the fort’s punishment cell, which was called the Black Hole by British soldiers. (The name continued to be used in army garrisons as late as 1863). Details of the story have since been disputed. Holwell’s numbers appear to have been exaggerated. More importantly, his claims of malice on the part of Siraj ud duala have been rejected. While it is clear is that the British prisoners were held overnight in a small, badly ventilated cell on the longest day of the year and that a substantial proportion of them did not survive, there is no evidence that the Nawab ordered the imprisonment or was even aware of it. British atrocities against Indian residents of Calcutta in the days before Siraj-ud-daula’s attack add balance to the story.

From the British point of view, retribution was rapid and thorough. Siraj ud duala’s attack on Calcutta was the first step in the events that would lead to the Battle of Plassey and the rise of the British Raj.

February 15, 2014

Seneca’s Tunnel? Or Virgil’s?

Traveling to Naples from the Roman resort of Baiae one day, the Stoic philosopher Seneca decided to travel by land instead of by sea. His chosen inland route included a famous tunnel built in Augustan times, the Crypta Neapolitana. But the claustrophobic and gloomy tunnel turned out to be not much better than a sea voyage. Afterwards Seneca wrote one of his famous ‘Letters to Lucilius’ describing his journey using terminology from the races and arena.

When it was necessary for me to return from Baiae to Naples, I convinced myself there might be a storm. Not wanting to endure a sea voyage again, I went by land. But the entire journey was so wet that I may as well have taken a voyage anyway. All the misfortunes of an athlete fell on me that day in the Naples Tunnel from the drenching* to the dusting*. No cramped starting gate at the races is longer than that tunnel, no torches gloomier than those that enabled us to see not through the darkness but rather the darkness itself. Had the place any other light sources it would still be clouded by dust which even in the open air is heavy and annoying. How much more so in that tunnel where it swirls back on itself. Shut up without any ventilation, it blows into the faces of those who stir it up. In this way we simultaneously endured two opposing inconveniences: on the same road, on the same day we battled both mud and dust. Letter to Lucilius LVII.1-2

The claustrophobic darkness of the tunnel plunged the philosopher into morbid musing on the nature of death and the soul (you can read his thoughts here) until the first glimpse of daylight restored him to his usual stoic cheerfulness and he claimed he was never actually afraid.

You can still see both ends of this tunnel – though not the middle, it has collapsed – in Naples today. In fact this tunnel was in constant use up until about a century ago, connecting Naples and Pozzuoli. The eastern (Neapolitan) entrance is found near the so-called Tomb of Virgil in the Parco Vergiliano a Piedgrotta. Located near Mergellina train station (only a half hour’s walk from Castel dell’Ovo) this Parco Vergiliano with an e is not to be confused with the Parco Virgiliano with an i four miles southwest near the little island of Nisida with its manmade causeway. In fact, the smaller park with Seneca’s Tunnel and Virgil’s Tomb is not even marked on Google maps. To find it, search for Church of the Madonna of Piedigrotta and zoom in a few hundred feet west to where the road enters a modern tunnel. On the left you will see the entrance to the site.

I was lucky enough to visit the Parco Vergiliano last September with Andante Travels. It is a cool green oasis in this Naples suburb, planted with herbs mentioned in the works of Virgil, all beautifully labelled with tile plaques giving descriptions and the Latin names. A dramatic cliff of famous yellow tufa is cloaked in ivy and dripping with vines. This soft rock is perfect for tombs and tunnels, which the Neapolitans call galleria. The biggest of these is the dramatic Crypta Neapolitana – Seneca’s tunnel. Next to it is Virgil’s so-called tomb. Nearby is another tomb, that of Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) the hunchback poet who was a great worshipper of Virgil.

I was lucky enough to visit the Parco Vergiliano last September with Andante Travels. It is a cool green oasis in this Naples suburb, planted with herbs mentioned in the works of Virgil, all beautifully labelled with tile plaques giving descriptions and the Latin names. A dramatic cliff of famous yellow tufa is cloaked in ivy and dripping with vines. This soft rock is perfect for tombs and tunnels, which the Neapolitans call galleria. The biggest of these is the dramatic Crypta Neapolitana – Seneca’s tunnel. Next to it is Virgil’s so-called tomb. Nearby is another tomb, that of Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837) the hunchback poet who was a great worshipper of Virgil.

Undaunted by the background noise of the Mergellina train and police sirens, our guide Richard Wallace read us Tennyson’s Ode to Virgil. Then he told us there is another possible tomb to Virgil on a higher level.

Climbing the brick stairs with the aid of a sturdy wooden handrail you will find a Roman aqueduct that ran above Seneca’s tunnel. You will get a good look at a niche with Madonna and Child carved into the entrance of the tunnel. Then, right on top is the second tomb that also might be Virgil’s, but probably isn’t. This atmospheric freestanding cylindrical tomb is of the columbarium type with niches for ash-filled urns. Someone has left a convenient tripod where you can burn fragrant bay leaves in memory of the great poet.

Although Virgil’s real burial place is probably lost in antiquity, he wasn’t forgotten. In fact, his fame grew and in the Bay of Naples he gradually came to be thought of as a great magician. According to legend he placed a magic egg somewhere in the eponymous Castel dell’Ovo. As long as the egg remains, the castle will stand strong. The clever poet invented a magic fly to keep away all other flies. He foretold the birth of Christ in his famous “Messianic Eclogue” and became Dante’s guide in the Inferno.

Although Virgil’s real burial place is probably lost in antiquity, he wasn’t forgotten. In fact, his fame grew and in the Bay of Naples he gradually came to be thought of as a great magician. According to legend he placed a magic egg somewhere in the eponymous Castel dell’Ovo. As long as the egg remains, the castle will stand strong. The clever poet invented a magic fly to keep away all other flies. He foretold the birth of Christ in his famous “Messianic Eclogue” and became Dante’s guide in the Inferno.

Best of all, Virgil created the Crypta Neapolitana in one hour, merely by looking at it intently, (not unlike Superman with his laser vision.)

According to one eighteenth century travel writer, the “grosso popolo” of Naples revered Virgil more for his creation of this tunnel than for the Aeneid. So it is fitting that you will find Virgil’s Tunnel near one or both of his possible tombs.

Caroline Lawrence is working on a new series of contemporary kids’ history-mystery books set in Naples, inspired by two recent trips to Italy with Andante Travels.

*For more on these technical terms, see Lacus Curtius

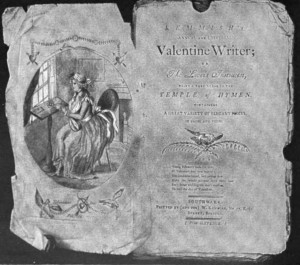

February 14, 2014

Happy Valentine’s Day!

The origin of today’s festival is murky, but it has been a tradition for centuries. By the Georgian period, it was a popular celebration much as it is now, and you could even commission a ‘Valentine Writer’ to pen your love letters for you. In London in 1791, The Star newspaper published a page of poems and thoughts on how this day for lovers had come about and how the day was represented in the literature of the day.

VALENTINE

—————

Arise, arise, sweet VALENTINE,

To see the Sun in lustre shine;

As liveried clouds around him wait.

Arrang’d in more than usual state;

Propitious on thy natal day,

While surly Winter slinks away

With all his ruffian blasts amain,

Disturber of thy gentle reign.Welcome Spring in mantle green

Whose emblem’s in my ANNA seen.

In whom lives all that nature taught,

Or fancy’s self from genius caught;

For truth must hail thee all divine,

My love, my hope, my VALENTINE.

J.F.

-There is a rural tradition on this day, birds chuse their mates; from when probably arose the custom of chusing Valentines, which affords an innocent exercise for the fancies of young people in various parts of Europe….Ghosts were anciently supposed to have the power of walking on the night of this day, when it became the custom in the followers of the Romish superstition to chuse on this day their Protecting Saints. On this day, in the North of England, and in Scotland, it is usual for young persons of both sexes to interchange presents. Pennant says, in his Tour of Scotland, that the drawing of Valentines is done there with great seriousness, as involving the future fortune of the married state. See also Dr. Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield, where, in a description of rustic manners, we are told it was always customary to send true love knots of Valentine morning.

-Valentine, whose name has been given on this day, was a primitive father of the Church, beheaded in the reign of the Emperor Claudius. [John] Gay has given us a pretty description of rural ceremonies observed on this day:

Last Valentine, the day when birds of kind

Their paramours with mutual chirpings find,

I early rose, just at the break of day,

Before the Sun had chased the Stars away;

A-field I went amid the morning dew,

To milk my kine, for so house-wives do;

The first I spied, and the first swain we see,

In spite of fortune shall our truelove be.

February 9, 2014

The ideal midwife?

By Helen King

What do we look for in a midwife? Short nails feature a lot in the history of midwifery!

Many images of midwives from the past are very negative, like this one from around 1800. In a previous post, I looked at midwives as murderers. Let’s return to the good sort now. Back in the second century AD, a doctor called Soranus wrote a book we now know as the Gynaecology. In consecutive chapters, he first answers the question ‘Who is able to become a midwife?’ and then turns to ‘Who is the best midwife?’ Any midwife, he says, should ‘know her letters’ – which could perhaps be translated as ‘have a basic education’ – so that she can appreciate the theory of midwifery as well as its practical aspects. She should be discreet, knowledgeable, with a good memory; strong, and a hard worker, with long thin fingers and short nails. The ideal midwife should be trained in all three branches of medicine: diet, surgery and drugs. This is a very wide-ranging role, particularly in view of later debates about what interventions a midwife could legitimately carry out. She should also be free from superstition or greed.

Other than a few sections on the anatomy of the female external genitalia published in 1556, Soranus’ work was lost during the Renaissance, only reappearing in the nineteenth century, and even then not in its complete form. However, various adaptations of his work survived. So his image of the midwife continued to be transmitted. Here’s James Wolveridge, in his Speculum matricis of 1670:

The best midwife is she that is ingenuous, that knoweth letters, and having a good memory, is studious, neat and cleanly over the whole body, healthful, strong, and laborious, and well instructed in womens conditions, not too soon angry, not turbulent, or hasty, unsober, unchaste; but pleasant, quiet, prudent…

Although he gives us this ideal, his aim was to defend men’s right to intervene in childbirth.

The 1656 Compleat Midwife’s Practice contrasted this ideal with the ‘many unskilful women’ who ‘in these days … take upon them the knowledge of Midwifry, barely upon the priviledge of their age’.

At the end of the seventeenth century Robert Barret’s A companion for midwives, child-bearing women, and nurses directing them how to perform their respective offices also drew very clearly on Soranus in saying that the ideal midwife

… ought to be neither too young, nor too Old, of a good habit of Body, her Hands small and gentile, with her Nails pared close, and without Rings, in the time of her Duty. She must be chearful, pleasant, strong, laborious, and inur’d to Fatigue; it being required that she should be stirring at all hours, and abiding a long time together with her Patient.

She ought to be Courteous, Sober, Chaste; of an even patient Temper; not apt to repine or quarrel: she ought to be Wise and Silent, not apt to talk foolishly of what she sees in the Houses where she hath to do; to observe the Humour of her Patient, and endeavour to divert her with what she finds most agreeable. She ought to be a Woman of Understanding, capable to counsel, advise, and Comfort the Person in Labour; to bear her up under despondency, to fortify her against Fear, or Immoderate Repining. Lastly, she ought to be a Religious, Pious Woman.

So Soranus’ ideal midwife has a long history. Even in the eighteenth century, when men-midwives were insisting on the importance of knowledge of the pelvic anatomy, other features in their lists of the qualities of the best midwife recall Soranus; for example, William Smellie’s A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery has her as ‘a decent, sensible woman of a middle age, able to bear fatigue’ who ‘ought to live in friendship with other women of the same profession, contending with them in nothing but in knowledge, sobriety, diligence, and patience’.

What strikes us today is that so much is about character, reputation and morality; midwifery has always been about rather more than ‘just’ training and experience!