Holly Tucker's Blog, page 62

November 14, 2013

Jan van Rymsdyk at The Dittrick Museum – Lucy Inglis

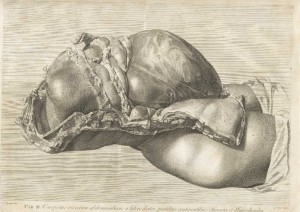

In 2009 I began researching Jan Van Rymsdyk and his contribution to the medical art of the eighteenth century. After a controversial allegation that women had been murdered by medical professionals to provide corpses for dissection, fellow Wonders and Marvels contributor Helen King and I shared our opinions on the subject. This left me even more intrigued by JVR. His life, as it turned out, held just enough mystery to be fascinating. He had worked for both the great man-midwives of the eighteenth century, William Hunter and William Smellie, still revered as pioneers by modern obstetricians. It was Van Rymsdyk who had illustrated, almost entirely, their two defining works: Smellie’s A sett of anatomical tables, with explanations, and an abridgement, of the practice of midwifery of 1754, and William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, Exhibited in Figures twenty years later. These books are still regarded as the moment modern obstetrics was born, through the labours of two supremely talented doctors. But Van Rymsdyk’s contribution has been largely ignored.

He was not only an artist, but at times, a drunkard, a comedian, and a deeply thwarted man. His life’s ambition was to be a portrait painter, yet his life’s work was a series of dead women and their children. The women’s faces are never depicted, but every detail of their children is captured and there is a curious dignity, almost an adoration in his renderings: the sitting posture of the gravid woman, with her knees covered by a blanket but her internal organs displayed by the neat flaying of the anatomist, the baby curled snugly inside her, a stray wisp of its hair escaping the womb. These images and their origin became a touchstone as I wrote Georgian London: Into the Streets. Whenever the past eluded me I returned to Jan Van Rymsdyk, the conflicted artist who brought his precise hand to those Soho dissecting rooms.

The more I read about Van Rymsdyk, Smellie and Hunter, the more interesting it became. It wasn’t just a story which made medical history, it was a scientific collaboration formed around the pivot of an artist. Both doctors were desperate to leave a legacy. Smellie wanted his advances in the use of forceps to continue helping women after his death. Hunter wanted his scientific discoveries on why women miscarried, presented still births and died in childbirth to ensure his fame. They both needed Van Rymsdyk. He worked fast, with pinpoint accuracy, recording the fresh corpses in a only a few hours. And his images had a strange allure, for all their gruesome reality; in them he managed to combine the Enlightenment ideal of beauty and truth. As Hunter said, the magic of Jan Van Rymsdyk is that he ‘represents what was actually seen, it carries the mark of truth, and becomes almost as infallible as the object itself’.

So, I am delighted to be collaborating with the Dittrick Museum in Cleveland, Ohio, on a temporary exhibition of their Jan Van Rymsdyk collection, to be shown in February. Dr Brandy Schillace and Dr Jim Edmonson are putting together a wonderful show based on JVR as both artist and a man working under some of the most challenging working conditions imaginable.

November 9, 2013

The Plague of Athens: dying like sheep?

By Helen King

I like sheep. When I was staying in the Netherlands some years ago, I was very excited because we were invited on a trip to what I heard as the ‘Sheep Museum’. Puzzled as to how there could be enough material to fill such a place, I went along enthusiastically, but was a little disappointed to find this was in fact a ‘Ship Museum’ (in Dutch it’s Het Scheepvaartmuseum). Oh well…

Wikimedia commons: modern Greek sheep

But how does a sheep die? In the Greek historian Thucydides’ famous/infamous description of the symptoms of the ‘Plague of Athens’, a hideous disease that struck the city during its war with Sparta in the fifth century BC and which killed its greatest general, Pericles, one phrase in particular acts as a useful warning about how difficult it is to translate original languages when studying history. At one point, Thucydides wrote ‘Appalling too was the rapidity with which men caught the infection; dying like sheep if they attended on one another; and this was the principle cause of mortality’ (Thuc. 2.51.4).

Explanations for this phrase have been very varied. Some regard this as an image – based on the point that sheep are flock animals, ready to follow a leader, it could mean simply that a lot of people died. This interpretation is reflected in a recent translation by Steven Lattimore, which has ‘from tending one another they died like a flock of sheep’. Another recent translator, Jeremy Mynott, makes this interpretation more explicit, with ‘they died in their droves like sheep’. It’s not a new suggestion; a mid-nineteenth century translation, by John South Phillips, had ‘they … kept dying like a flock of sheep’. Or the phrase could suggest that they died passively, unable to resist the disease. However, some have seen it as suggesting that the sheep were dying too, and thus as evidence that the mysterious condition that affected Athens was a zoonosis, a condition that can be passed from animals to humans.

The translation with which I started this discussion was that of Benjamin Jowett, first published in 1881. An even earlier one, by William Smith in 1753, included ‘that mutual tenderness in taking care of one another, which communicated the infection, and made them drop like sheep. This latter case caused the mortality to be so great’. ‘Dropping like sheep’ is not exactly an idiomatic expression today, although we do talk about ‘dropping like flies’.

So, you rightly ask, what’s the original Greek here? Transliterated, it comes out as ‘hôsper ta probata’, literally ‘just like the sheep’. Some scholars have found the use of the definite article very exciting here – not ‘just like sheep’ but ‘like THE sheep’. Does that make it more likely that actual sheep were dying? No: Greek uses of the definite article are not the same as ours.

The range of interpretations of this apparently simple phrase remind us once again of the much-repeated claim that every translation is already an interpretation. If we don’t have competence in the original language, we can at least think about the range of translations offered, and – for ancient Greek or Latin at least – consult a modern commentary on the text which talks us through the options. In this case, translations depend on the knowledge of medicine of the person who is doing the translating (and of the period in which he or she is writing), and on what that person wants to propose as the diagnosis of this most undiagnosable of afflictions!

November 8, 2013

LeRoy Buffington’s claim to have invented the skyscraper

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

William Le Baron Jenney’s Home Insurance building of Chicago, whose status as America’s first skyscraper Buffington disputed

Throughout his long career as an architect, LeRoy S. Buffington insisted that he had invented the skyscraper. Forget, Buffington urged, the work of William Le Baron Jenney, the Chicago architect who in 1883 designed the structure most often identified as the first American skyscraper.

Buffington, a Cincinnati native who spent most of his career in Minneapolis, was no crank. From 1871 until his death in 1931 at age 83, he designed state capitols, hotels, university buildings and private residences all around the Upper Midwest.

A tall building with a braced metal skeleton that supports its walls is the most basic definition of a skyscraper. Such a project had never been undertaken before the final decades of the nineteenth century in part because many architects and engineers of the time believed that iron was intrinsically incompatible with masonry as a building material.

During the 1880s, Buffington launched an investigation to find out if anyone had ever patented a system of building construction using a braced metal skeleton with supporting shelves for all walls. Turning up no such patent, he spent nights and weekends perfecting his own skeleton system. “I decided to take a column for my model, a solid base, a plain shaft with upward lines like volutes, and a beautiful cap and skyline to finish,” he wrote. “This was the design of my 28-story building.” That same year, he notes, he also designed exteriors for a building that rose 50 stories and 600 feet and a “cloudscraper” that towered 100 stories and 1,320 feet. These drawings, signed and dated, survive today. By the standards of 1882, all three designs were monstrous in height.

Buffington’s writings make it clear that patenting a metal skeleton system was the ultimate goal of his work. Much happened in the six years between Buffington’s claimed development of a skeleton system and his receipt of a patent. William Le Baron Jenney’s Home Insurance building had marked the Chicago skyline, and Jenney had publicly detailed the project in a trade-journal article and in a talk before members of the American Institute of Architects, both in 1885.

But once he acquired his patent, Buffington expected that builders of any structure using a metal skeleton frame with shelves to support walls would have to pay him a royalty. In the 1890s such buildings began sprouting in several U.S. cities, and Buffington organized the Iron Building Company to license his patent and collect fees. Not surprisingly, builders resisted compensating Buffington and seem not to have taken his patent seriously. The architect retaliated with legal action. The outcome of the first of many lawsuits, Iron Building Company vs. William E. Eustis, filed in December 1892, set the pattern for those that followed. The court ruled against Buffington, noting that the patent protected the specific construction scheme detailed in the patent application, not the entire concept of metal-skeleton construction with wall-supporting shelves.

Reeling from the loss of $30,000 he spent to press his lawsuits, Buffington filed for bankruptcy in 1901. By then, his best architectural work was behind him.

Recognition came at last in 1929, two years before his death. Rufus Rand, the builder of a new Minneapolis office tower, voluntarily paid the aged architect a royalty of $2,250. Buffington’s patent had long ago expired. Appearing dazed at the news, Buffington told a reporter, “It hardly seems possible. I can’t believe there is a man in Minneapolis that would do this — or a man anywhere else in the world for that matter. I don’t know what to think.” Rand explained his motivation simply: “I sympathize with him in the lack of praise that has been his.”

Further reading:

Millett, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: The Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007.

Tselos, Dimitris. “The Enigma of Buffington’s Skyscraper.” The Art Bulletin, March 1944.

Upjohn, E.M. “Buffington and the Skyscraper.” The Art Bulletin, March 1935.

November 6, 2013

A Giant Roman Emperor: Maximinus

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

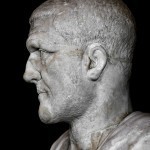

In AD 235 a giant became the most powerful man in the Roman Empire. Maximinus of Thrace (Bulgaria) was a simple shepherd when his impressive size and strength attracted the attention of the Roman emperor in AD 202. Maximinus wrestled 16 of the emperor’s burliest soldiers. Then, only slightly winded, he raced the emperor’s horse and went on to overcome 7 more hefty legionnaires. The Thracian colossus was inducted into the army on the spot. Maximinus rose through the ranks, proving himself such a beloved leader that he was given supreme command of the imperial army. In AD 235 the army and the Senate proclaimed him Emperor of Rome.

Ancient Roman writers claimed that Maximinus Thrax stood over 8 feet tall. His sandals were said to be twice the size of regular army issue. He wore his wife’s bracelet as a thumb ring. It was said he devoured 40 pounds of meat and 18 bottles of wine at each meal. They claimed he crushed rocks in his fists, out-pulled a team of horses, and knocked out a mule with one punch. These are all exaggerations, of course. Unless his skeleton is discovered someday in a coffin, his exact size remains unknown. But the detailed descriptions of his appearance and portrait busts suggest that the huge Bulgarian probably suffered from a form of acromegaly. Of “frightening appearance and colossal size,” he displayed a prominent forehead, large nose, and lantern jaw, typical symptoms of pituitary gland overproduction of growth hormones.

Most sufferers of gigantism do not live long lives, but Maximinus died at age 65 in AD 238. He might have lived longer, but during his reign, his popularity plummeted. Of humble barbarian origins, he hated Roman aristocrats and became paranoid and brutal. The public turned against him, taunting him with the nickname “Cyclops.” During an unsuccessful siege, his soldiers turned against him. Maximinus was assassinated as he slept on his immense cot in his tent by his own Praetorian guards.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

November 2, 2013

Ancient Roman Girl Athletes

by Elizabeth C. Goldsmith (W&M Contributor)

When I was a girl in high school back in the ‘60s, the only team sports available to me were swimming and field hockey. By the time my sister hit high school they had added Cinderella softball and Powder-Puff football. After Title IX, things changed. That’s the modern history of women’s sports.

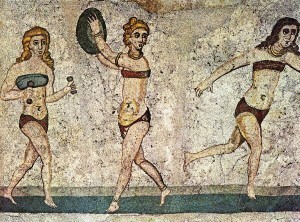

These thoughts returned to me on a recent trip to Sicily, when I visited the Villa Romana del Casale, a Roman site dating to the early 4th century. It is a grand ruin, the residence of a high-ranking member of the Roman senatorial aristocracy, possibly the governor of the region, which was rediscovered in the late nineteenth century after having been buried in a mudslide that occurred sometime in the 1200s. The dirt and silt had a protective effect, with the result that the mosaics covering the floors of the residence are almost completely intact, making it the largest and best preserved display of ancient Roman mosaics in the world.

There is a grand hallway some 60 meters long covered with mosaics depicting Roman hunters in Africa trapping lions, elephants, rhinoceroses, and tigers and loading them on ships to bring them back to Rome for blood sport entertainment in the Colosseum. There are mosaics depicting amorous mythological scenes in what were the guest bedrooms of the villa, while sea monsters and fishing Cupids adorn the floors of the baths. There is a mosaic of angelic children riding in chariots drawn by ostriches and other birds on the floor of the room that served as a nursery. But the  room that took my breath away was one that might have served as a home gym. It is covered with mosaics of young women engaged in sports, receiving laurel crowns for winning competitions, and just … working out. The images are dubbed “The Bikini Girls” on the museum labels and in guidebooks. I was told that this label is due to the fact that archaeologists in the 1950s thought the mosaics were depicting some kind of beauty contest. They hadn’t ever seen girls lifting weights and wearing sports bras. In the last few years commentators have been trying to revise the label and call the mosaics “The Athletic Girls”.

room that took my breath away was one that might have served as a home gym. It is covered with mosaics of young women engaged in sports, receiving laurel crowns for winning competitions, and just … working out. The images are dubbed “The Bikini Girls” on the museum labels and in guidebooks. I was told that this label is due to the fact that archaeologists in the 1950s thought the mosaics were depicting some kind of beauty contest. They hadn’t ever seen girls lifting weights and wearing sports bras. In the last few years commentators have been trying to revise the label and call the mosaics “The Athletic Girls”.

The Villa Romana del Casale was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1997, a few years after another important Unesco document was released, designating the practice of physical fitness and access to sports a basic human right. We don’t normally associate 4th-century Rome with women’s freedom, but when it came to athletic opportunities for girls – well, some girls -, they were ahead of the game.

October 29, 2013

Hobgoblin Classification in the Eighteenth Century

By Lisa Smith

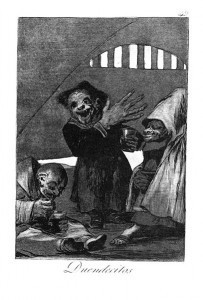

Goya, Duendicitos (elves), Los Caprichos, 1799. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The modern goblin might be mean and ugly, but early modern goblins were a different breed: helpful, if mischievous, creatures. The shift began in the eighteenth century when goblins went extinct.

Augustin Calmet, a Benedictine monk, included two chapters on goblins in his Dissertation (1746), where he provided evidence of goblins from “unexceptionable witnesses”.[1] Typical goblin behaviour included looking after horses, helping in the house, or working in the mines. John Brand (1777) also noted goblins’ helpfulness, “provided they were civilly used”.[2]

Goblins could be naughty. Pliny the Younger, Calmet tells us, had a household goblin. A freed man, who slept with a younger brother, dreamed once that someone was cutting his hair. On waking, the freed man discovered that his hair had been cut and scattered around the room. A few nights later, a young boy in the household—who slept in a room with several others—had the same thing happen.

Some goblin tricks were troubling. In one 1745 case, a French soldier stationed in Flanders complained three times to his captain, Count Despillers, about being unable to sleep. Despillers only took him seriously when the soldier, “no fool” and known for bravery, threatened to desert. The Count decided to spend the night in the room, but ended up leaving shortly after midnight, confused by the noises in the room… and the bed that had been overturned with both men in it. The next morning, the soldier had a new room.

Calmet also wanted to define what sort of creature goblins were. One story from Johannes Trithemius (d. 1516) showed what happened when a goblin was unappreciated. Hecdekin (spirit in a cap) lived in Hildesheim, Saxony, where he worked in the Bishop’s kitchen. After another servant offended him, Hecdekin complained to the head cook who proceeded to ignore him. Hecdekin “thought it proper to do himself justice”: strangling the servant, tearing him into pieces, and boiling him. This got everyone’s attention, who drove Hecdekin away by exorcism.

Calmet stressed goblins’ helpfulness and lack of malevolence, which meant that they were not devils. They only became dangerous when angered, like Hecdekin. But neither were they angels, their “waggish tricks” lacking dignity. Goblins were somewhere in between.

Brand classified the goblins linguistically. They were the same as Brownies in Scotland, related to fairies, and “a Kind of Ghost”. Brand believed that ‘goblin’ came from ancient Greek, meaning ‘house spirit’, and that hobgoblins were a species known for hopping on one leg. The name ‘Brownies’ referred to their swarthy colour, which came from their hard labour. The origin of the belief itself, Brand suggested, was Persia or Arabia. However, since Samuel Johnson had noted that no one had spoken of Brownies “for many years”, Brand thought they were extinct.

Goblin beliefs were, indeed, changing. Calmet might have dismissed the existence of vampires, but he believed in goblins because of good eyewitness accounts. William Bourne in 1725—and Brand who agreed with him—would have seen this as Calmet’s popish credulity. Goblins only flourished “in the benighted Ages of Popery, when Hobgoblins and Sprights were in every City and Town and Village”. These were stories told around winter fires that added “to the natural Fearfulness of Men, and makes them many times imagine they see Things”. Goblin extinction, then, was a move from superstitious excess (as Bourne and Brand saw it) towards reason. The classification of goblins was a way of putting them in their place.

Some of these stories are easily explained: a prankster in Pliny’s house, a murder in Hildesheim, a literary trope about terrified soldiers. All the same, if you should ever receive unexpected help around the house, remember to say thank you. Just in case.

[1] Augustin Calmet, Dissertation upon the apparitions of angels, demons, and ghosts, London, 1759. (Original French, 1746.)

[2] John Brand republished and added a commentary to William Bourne’s 1725 work on popular antiquities: Observations on popular antiquities: including the whole of Mr Bourne’s Antiquitates Vulgares, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1777.

Lisa Smith (@historybeagle) is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and teaches on medicine, natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe.

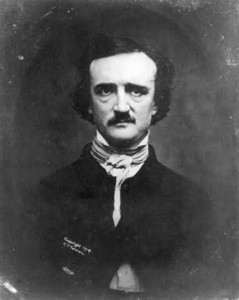

Searching for the ghost of Edgar Allen Poe in New York City

by Stephanie Cowell

He died in poverty and was found in clothes not his own. He was only forty years old. Two years before he had lost his wife/cousin whom he had married when she was thirteen. 164 years after his death, we are still searching for him.

This month and through January 26th the New York City’s Morgan Library is featuring an exhibition devoted to his work. It includes a piece of his corroded coffin, old newspapers with his stories in such tiny print one wonders anyone could see in those days (how did they set type so small?) His writing is hardly bigger, written on small pieces of paper glued together, and in one case, a scroll. There are only a few photographs and drawings. He made a living as a journalist. People loved the macabre then as today and he supplied stories. His was a great intellectual mind and he died too soon. One wonders that his work survived above all the other journalists turning out poems and stories for the many newspapers in the dirty, crowded streets of New York in the 1830s and 1840s.

I read Annabel Lee written in his handwriting. It was supremely moving.

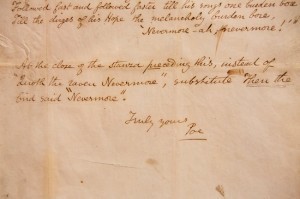

Poe’s instruction to his publisher revising The Raven

But why should I not search for him? He lived four blocks from me on a street renamed for him; there was also a café called Edgar’s when I would drink coffee with friends (this café is unfortunately closed.) And of course his house there is gone, swept away a long time ago, perhaps before they began to turn New York’s Upper West Side from farmland to middle-class housing.

Then on a misty October evening (it was truly!) I was invited to attend a Poe ghost walk, given by the Ghosts of New York Walking Tours in conjunction with my friend the novelist Lynn Cullen, whose novel Mrs. Poe appropriately debuted this month. A small group of us gathered in front of 116 Waverly Place in the heart of Greenwich Village. In 1845, Poe walked up those steep steps to a literary gathering to first read his poem The Raven. I looked at the steps and then down the street over the cars to the bright lights of a coffee shop. How New York has changed! The new owner of the old house says she has sometimes heard footsteps on the wood floor above her. But there is no one there.

After learning about the house, we walked through Washington Square Park with the street lamps glimmering through the trees. The area has been a graveyard, the guide told us, and the bones of twenty thousand people lay beneath our feet. That gave me pause for thought. It was already a public park when Poe lived nearby, but the fountain which was possessed by guitar-playing hippies in the 1960s and the famous Arch were not yet created.

Lynn Cullen’s novel MRS. POE

As she explained all this, a brooding man in his thirties with strange genius in his eyes seemed to walk under the trees and disappear. But then, all my friends know that I feel ghosts.

So happy Halloween, and if you are in the mood to read a little Poe (a poem or a terrifying story) this is the very month to do it!

______________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

October 20, 2013

Mysterious Mystics

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

It’s striking how much of medieval women’s literary output is description and explication of mystical visions. Why were so many medieval mystics female? Why did so many women claim to receive visions from God or the saints?

The reasons, paradoxically, are related to women’s lower status in society and the Church. First, women were considered to be more primitive than “intellectual” men and thus their connection with the Divine was more direct. This was reflected in their writing: since few women had the education to write in Latin, their writing in the vernacular “made possible a direct, unmediated relation with the Holy Ghost.”[i] Since a mystic was essential a passive conduit for the word of God, anyone, including an uneducated woman, might (if she were worthy) be chosen to take this role.[ii]

Also, since many positions of authority in the Church were denied to women, a woman feeling a connection to the Divine could not become a priest, much less rise in the Church hierarchy (legends like that of Pope Joan, a woman pope of the ninth century notwithstanding). But “[v]isionary women could bypass the human, male, authority of the Church on earth, and claim to be the instruments of a higher, divine authority.” Not only did this give them a powerful voice, but also “[i]n this way, . . . they could validate their activity as writers.”[iii] At a time when “Christianity . . . came to forbid women the genre of the sermon; it tolerated–even feared and revered–their visions.”[iv]

Hildegard von Bingen, probably the most famous medieval mystic, dictating a vision represented by flames coming from (or going to) her head

The Church hierarchy did manage to get involved, of course. No one could expect to have her claim of mystical experience accepted without question. Doubtless in an out-of-the-way village a woman could be revered as a visionary with no stamp of authority, and some women—and men—undoubtedly were called mystics without validation from the authorities. But these people ran the risk of being accused of heresy for taking the word of the Devil as the word of God. The Church developed mechanisms to recognize what it considered “true” visions, often including a kind of trial, or an interview with an established mystic, or some other test.

Most mystics followed a relatively orderly progression in their visionary life.[v] First came purgation and self-loathing, often characterized by anorexia (which sometimes lasted the duration of the mystic’s life). The next step often involved more outward-looking evidence of a special gift: telling someone what scandal she is hiding, for example, or what is his secret wish. Some mystics would then claim they had authority to interpret the Bible—a dangerous step, for a thin line divides interpretation and preaching, a practice strictly forbidden to women. Next would usually come devotional visions that arose from meditation on a saint, usually the Virgin Mary, or Christ.

Almost invariably the mystic would then have an experience of Christ’s crucifixion, and—what often strikes modern readers as odd and unsettling—frequently a visionary experience of sexual union with Christ. Medieval thinkers did not have as much of a problem accepting this kind of vision as do moderns: The mystic was in effect wedding Christ through her visions, and a marriage, after all, must be consummated. Also, erotic and spiritual ecstasy were—and often still are—closely linked, for both men and women. Margery Kempe, although desperate to be declared a legitimate mystic, was honest enough to admit that although Christ appeared to her naked, she wasn’t able to do more than grasp his toes!

The last stage was a vision of universal order. When this step was achieved, the vision attained was frequently very difficult for the mystic to explain and others to understand. Today this difficulty tends to either attract readers eager to puzzle out the mystery, or repel those baffled by the vision’s opacity.

[i] Danielle Régnier-Bohler, “Literary and Mystical Voices,” in Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, ed. A History of Women in the West. Vol. II: Silences of the Middle Ages. Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992, p. 447.

[ii] See, for example, the ancient Greek Pythia who spoke with the voice of Apollo at the Oracle at Delphi. She was invariably an uneducated peasant woman.

[iii] Alexandra Barratt, ed. Women’s Writing in Middle English. London and New York: Longman, 1992, p. 8.

[iv] Julia Bolton Holloway, Constance S. Wright, and Joan Bechtold, eds. Equally in God’s Image: Women in the Middle Ages. New York: Peter Lang, 1990, p. 3.

[v] Adapted from Elizabeth Alvilda Petroff. Medieval Women’s Visionary Literature. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University, before transitioning to being a full-time writer. Visit her website and her blog.

October 18, 2013

Drug Wars

by Pamela Toler

A growing number of addicts. A ruthless business cartel. A country determined to close its borders to imported drugs. Violence and corruption in major cities. Sound familiar?

Welcome to the Opium War of 1839.

In the late eighteenth century, opium was a key element in the British East India Company’s business plan. The company grew opium in India and sold it in China, using the proceeds to pay for porcelain, tea and silk for the market back home in Britain. By the 1820s, the British were shipping enough opium to China each year to supply a million addicts, and the market was growing.

The Chinese government rightly saw imported opium as a threat to society. Opium smoking not only destroyed individuals, it destroyed families. (You want a lecture on family values? Read Confucious.) The high price of opium led to violence and corruption. The drain of silver payments for opium threatened the country’s economic base. The Chinese made the import and production of opium illegal in 1800, but their efforts to enforce the ban were unsuccessful.

Britain, in its turn, wanted China opened up to free trade. The Chinese limited foreign trade to the port of Canton (now Guangzhou). Within Canton, foreign merchants were subject to further limitations on where they could live and trade, when they could trade, and who they could trade with. In 1793 , the British government sent Lord Geroge McCartney on diplomatic mission to China with the goals of establishing diplomatic relationships with the Chinese government and opening trade. The Chinese Emperor sent a condescending note to King George III explaining his refusal: “We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your country’s manufacture.” A second mission in 1816 under the leadership of Lord Amherst was dismissed by the Chinese due to Amherst’s refusal to follow the ceremonial forms of the Chinese court.

In 1838, the Emperor sent an Imperial Commissioner to Canton to stop the opium trade–basically a drug tsar by another name. Lin Zexu successfully suppressed the Chinese opium sellers, but was forced to barricade the foreigners in their warehouses before they surrendered their merchandise.

Lin Zexu confiscated and destroyed 20,000 chests of illegal opium from British warehouses. The British responded by sending sixteen British warships to China. Between 1839 and 1842, the British navy attacked and blockaded Chinese ports, sank Chinese ships, occupied Shanghai, and sailed up the Yangzte River to threaten the city of Nanjing. Their immediate goal was ‘”satisfaction and reparation” for the insult and loss of British property. If they happened to force the Chinese to agree to more acceptable commercial privileges at the same time, that was gravy.

The 1842 Treaty of Nanking opened five treaty ports to Western trade, gave the British what was then the barren island of Hong Kong, paid reparations to British merchants for lost property, and gave foreign merchants extra-territoriality (always the thin edge of the wedge when it comes to losing control of your country). Neither side was happy with the provisions of the treaty, making a Second Opium War almost inevitable.

October 14, 2013

Looking for Virgil, finding Tony Soprano

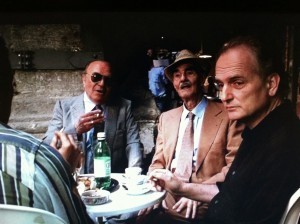

Tony & Annalisa at Lucullo in Bacoli

When we visited Pompeii and Herculaneum a dozen years ago, everybody warned us to avoid Naples like the plague! They spoke of gangs of street-urchin pickpockets who would descend on us like locusts, fleets of Vespa-riding handbag-snatchers, piles of garbage and walls covered with rude graffiti. And then there were the suicidal drivers. In Milan, goes the saying, traffic lights are the law; in Rome they are a suggestion; in Naples they are Christmas decoration!

So in the year 200 we barely popped our heads above ground when arrived at Naples train station from Rome. We scuttled along to the Circumvesuviana and only breathed a sigh of relief when we were safely on the train to Sorrento. On a return visit in 2005 my husband and I stayed at charming but remote Sant’Agata sui Due Golfi and used ferries, buses and taxis to visit Misenum, Baia, Ischia and Piscina Mirabilis. It was fun but cumbersome and not entirely successful. The Piscina Mirabilis was closed and we couldn’t manage to fit in Sofatara or Cumae. How much easier if we had made Naples our base! But we didn’t realise that then.

Santa Lucia hotel, Excelsior, Vesuvius, Santa Lucia fountain

Then, last January my husband and I went on our first Andante Travels Tour to Pompeii and Herculaneum. It was fabulous. Our brilliant and learned lecturer, Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, proceeded to explode one myth after another: ‘Vesuvius’s first eruption wasn’t on 24 August; don’t call it a lararium; don’t call it the Decumanus Maximus; we don’t know if this is the Villa Poppaea; we don’t even know if this place is called Oplontis.’

And another myth: ‘Don’t be afraid of Naples,’ he said. ‘It’s a vibrant, exciting city. Be sensible and keep your money and valuables out of reach, but enjoy it!’ So, we took his advice and booked another Andante Tour which would be based in Naples. Land of the Sibyl, our tour was called, and it promised us sites we’d tried to visit before such as the Piscina Mirabilis, Solfatara and Cumae (home of the Sibyl).

My reason for returning to this part of the world is that I am hoping to do a Young Adult retelling of Virgil’s Aeneid. The poet from Mantua (Virgil) was based in Naples and I wanted to connect with him.

Santa Lucia fountain, Naples

The excitement started for me when Andante told us we would be staying at the Grand Hotel Santa Lucia right down on the waterfront. I Googled the hotel and thought it looked vaguely familiar. I had seen that arch somewhere before. Then I remembered: in an episode of the ground-breaking, award-winning TV series The Sopranos. In season 2, aired in the year 2000, Tony (a mafia don from New Jersey) and two of his men go to Naples. I looked up Commendatori, and sure enough, it was the same arch: the Fountain Santa Lucia. Tony stayed at the Hotel Excelsior and ours was right next door.

From that moment on, the bard from Mantua was overshadowed by the don from New Jersey. Played by the brilliant , (who sadly died in Rome this summer), Tony Soprano is not likeable but he is compelling.

The first full day after our arrival I coerced some of my fellow travellers to venture inside the Hotel Excelsior. We walked through the plush lobby where Tony is first addressed as commendatore, “commander”. Up on the 8th floor we discovered a gem of a bar with stunning views of Vesuvius. The famous volcano was lit golden by the setting sun behind us. Sipping our Campari sodas and nibbling typical Neapolitan tidbits, we felt like Mafia dons and donettes.

Commendatori incl. David Chase (right)

A few days later our tour took us into the centre of Naples. It is a vibrant noisy city full of colour and life. The ancient road called Spaccanapoli is supposed to be the charming one, but I preferred Via dei Tribunale with its vegetable stalls, cafés, graffiti and a wonderful bulldog. This is where Paulie goes to have an espresso and greets some Italians at a nearby table with a cheerful ‘Commendatori!’ The three Italians, (one of whom is series creator in a cameo role), ignore him. In real life, Neapolitans are very friendly.

One day we went to Virgil’s tomb just a short distance from our hotel. In the gardens surrounding the tomb was a marble bust of the poet along with shrubs and trees mentioned in Virgil’s three works, next to signs with relevant excerpts. But I didn’t feel any sense of the bard, despite a tripod and garland of flowers left by another Virgil fan in the lofty tomb. (below)

Opposite our hotel was a delightful castle called Castel dell’Ovo AKA the Castle of the Egg. This is where the medieval Neapolitans believed Virgil, who by now was considered a magician, kept his magic egg. As long as the egg was safe, it was believed, Naples would prosper. The little cobbled village at its foot was pretty enough to be a film set and indeed, they were filming the remake of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. the week we were there, and a helicopter was constantly buzzing around, filming establishing shots.

Virgil’s tomb?

In Commendatori, Tony meets Annalisa, the stunning daughter of the former head of the local Mafia (suffering from dementia) and wife of the current head (suffering from life imprisonment). So she is in fact the acting head of the local Mafia. Tony finds it hard taking orders from a woman, but I met several beautiful, dynamic and powerful women in Naples, two of them the head teachers of schools. Tony and Annalisa have seafood lunch in front of another castle and the OMLIN shipyard, then they go walking on a beach. I kept my eyes open for this location and found it on the day we visited Baia. Baia (or Baiae as it was known 2000 years ago), was the St Tropez of the Roman World: a place of decadence and immorality where men bathed with women. I used it as the setting for my 11th Roman Mystery, The Sirens of Surrentum.

Bacoli seen from the ruins of Baiae

After visiting the so called Temple of Mercury, with its flooded floor and atmospheric dome, and saluting the upside down fig tree in a vault nearby, we had lunch down at the seafront in Bacoli at a pretty beige building called Locanda dei Re. After lunch, I skipped dessert to see if I could find the exact location of Tony’s lunch with Annalisa. It turned out to be a seafood restaurant called Lucullo. Appropriately, Lucullus was an ancient Roman famous for his banquets. Back in Naples the Castel dell’Ovo is built on the foundations of his once opulent villa. In the scenes between Tony and Annalisa you can see Locanda dei Re next to some other pretty pastel coloured restaurants. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. helicopter was buzzing around here, too.

On our final day of the tour we went to Cuma. At last! The Sibyl! But once again Virgil was eclipsed by Tony and friends. Cumae is where Annalisa ‘prophesies’ Tony’s future and also propositions him. He is tempted by her, but wisely demurs. I was glad to see they’ve cleaned up the garbage since they filmed that episode fourteen years ago. In fact Naples was remarkable free of garbage and the graffiti was mostly delightful. My husband and I supplemented our Andante Tour with one of the open top tourist buses and it was great fun. We also listened to Rick Steve’s excellent podcasts and read Naples 44, the harrowing and hilarious wartime diaries of Norman Lewis.

When Tony arrives back in New Jersey, you can see the regret on his face. He has obviously fallen in love with Naples and regrets leaving. So don’t be squeamish about visiting this most vibrant and beautiful city. Wear a money belt, or just take small notes spread about your person. Be sensible and you’ll have a great time.

Like Tony Soprano, I fell in love with La Bella Napoli and hope to return soon. And next time I WILL find Virgil!