Holly Tucker's Blog, page 66

June 18, 2013

do you want to write a historical novel?

Everyone has a novel in her, apparently! Is yours a historical one? Would you like to give it a kick start by attending an event at which you could get advice from novelist V.M. Whitworth and others?

I belong to a very lively network of midwives and academics who work on the history of midwifery: the De Partu History of Childbirth Research Group. The Chaiir, Janette Allotey, has put together an event to be held at the wonderful venue of Crewe Hall on 23 August 2013, with the option of attending as a day visitor or staying overnight. If you look on the website you will find out more and be able to book! The event is aimed at academic historians, especially historians of childbirth and nursing, but all are welcome.

Deciphering the Indus Valley

by Pamela Toler

Around 2500 BCE, the first cities appeared on the banks of the Nile in Egypt, at the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates in ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), and in the valley of the Indus River in what is now Pakistan and northwest India India.

Thanks to the Old Testament, traveling museum exhibitions, and popular media, most of us know a little about the civilizations of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. We have clear images in our heads of mummies, the pyramids, the Sphinx, King Tut and Nefertiti. Assyria, Nebuchadnezzar, and the hanging gardens of Babylon are familiar names.

But how much do you know about the Indus Valley civilization? My guess is, not much. No one does.

Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, the ruins of the Indus Valley civilization are not glamorous. There are no palaces, no temples, no public monuments. (There was, however, piped water. Given a choice, would you rather have pyramids or plumbing? Me, too.) Centered on two main cities, Harappa and Mohenjo-Dara, the remains of the culture are scattered over an area of 1.2 square kilometers. The cities are laid out in a grid design that feels familiar to anyone who knows the American Midwest. The buildings are made of uniform brick and are relatively unadorned. (Sounds like Chicago, doesn’t it?)

Also unlike ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, scholars have not deciphered the Indus Valley script. With no public monuments and no preserved documents, most of our examples of the script are limited to very short samples contained on the small engraved seals that are the most typical artifact of the Indus Valley civilization. Not a great sample for a project that depends on the numbers.

There have been more than a hundred separate attempts to decipher the script, with little success. Thanks to a group of Indian mathematicians and computer scientists, led by computational neuroscientist Rao Rajesh, we’re closer than we’ve ever been. Keep your fingers crossed.

June 15, 2013

Modern Evil Eyes

The more I try to find differences between the Romans and ourselves, the more similar we seem. Recently I’ve been thinking about charms against evil. In researching my Roman Mysteries books, I noticed that Romans seemed to employ three types of visual charms against evil. left: two modern versions of ancient evil eyes.

1. The first category of apotropaic devices I’ve seen are male or female GENITALIA. These can be painted on walls, carved into paving stones, worn as amulets or formed with the hand. I have heard it suggested that these cause laughter and thus defuse ill-will.

1. The first category of apotropaic devices I’ve seen are male or female GENITALIA. These can be painted on walls, carved into paving stones, worn as amulets or formed with the hand. I have heard it suggested that these cause laughter and thus defuse ill-will.

2. The HAND (usually the unlucky left hand) extended PALM FORWARD to ward off something unpleasant. (This is called the Hand of Miriam in Jewish lore and the Hand of Fatima in Muslim countries.) Sometimes the hand has an added eye, the most powerful apotropaic symbol of all.

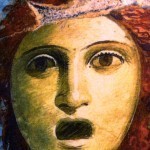

3. FACES or EYES looking back at the viewer. These counteract the “evil eye”, a powerful gaze of envy or malice. Medusa’s face and actors’ masks, like the one from Pompeii, (above) are the most common examples of this. These eyes are almost always blue.

We would probably like to think that we are less superstitious than the ancient Romans, but I’ve just spent a week in Scotland with the Scottish Book Trust and came across the third category of image everywhere. (Funded by the Scottish Friendly, the Scottish Book Trust takes authors into schools that might not be able to afford author visits in the normal course of events. My particular tour took place in the area called Midlothian south and east of Edinburgh.)

We would probably like to think that we are less superstitious than the ancient Romans, but I’ve just spent a week in Scotland with the Scottish Book Trust and came across the third category of image everywhere. (Funded by the Scottish Friendly, the Scottish Book Trust takes authors into schools that might not be able to afford author visits in the normal course of events. My particular tour took place in the area called Midlothian south and east of Edinburgh.)

While visiting schools, historic castles and a book festival, I spotted seven different categories of faces or eyes to “turn away evil”:

1. The evil eye in nature! On our second day of touring we stopped for lunch at a garden center with a Butterfly World nearby. I realised that many animals have NATURAL EYES to frighten off predators, their own version of evil.

2. Faces on and in buildings. We stayed in a magnificent hotel called Carberry Tower that was a castle once occupied by Mary Queen of Scots. A wooden Flemish fireplace had little cherub’s FACE looking out and molded plaster ceiling panels had Mary’s FACE looking down, too. (right)

2. Faces on and in buildings. We stayed in a magnificent hotel called Carberry Tower that was a castle once occupied by Mary Queen of Scots. A wooden Flemish fireplace had little cherub’s FACE looking out and molded plaster ceiling panels had Mary’s FACE looking down, too. (right) 3. Statues and mannequins. The current owner of Carberry Tower has placed a mannequin dressed up as a MONK on an upper gallery of the reception room. There are other statues in the courtyard. I don’t know if they are consciously against evil but they are extremely unsettling.

3. Statues and mannequins. The current owner of Carberry Tower has placed a mannequin dressed up as a MONK on an upper gallery of the reception room. There are other statues in the courtyard. I don’t know if they are consciously against evil but they are extremely unsettling.

4. In one of the schools we visited, a Don’t forget to wash your hands decal on a glass door looks just like a modern version of the “hand of Fatima”. It is even the “sinister” left hand.

5. In another school we were given a visitor’s badge with a SMILEY FACE Does this iconic symbol avert evil by making us smile? A circle with a curved smile line and two eye-dots is recognisable to babies as a human face and will elicit a smile in return.

6. In the pretty town of Haddington, our base for the second half of the week, we spotted this neighborhood shop watch EYE SIGN (right) in several shops. This reminded me of the recent news from Newcastle: that an image of staring eyes overlooking bike racks caused thefts there to drop dramatically.

6. In the pretty town of Haddington, our base for the second half of the week, we spotted this neighborhood shop watch EYE SIGN (right) in several shops. This reminded me of the recent news from Newcastle: that an image of staring eyes overlooking bike racks caused thefts there to drop dramatically.

7. On our last day we went to the Borders Book Festival in the pretty border town of Melrose. Within five minutes of arriving I saw two different women wearing BLUE BEAD BRACELET. One bracelet even had the hand of Fatima beside the apotropaic blue “eye bead”. (left) The eye-bead design goes back millennia.

7. On our last day we went to the Borders Book Festival in the pretty border town of Melrose. Within five minutes of arriving I saw two different women wearing BLUE BEAD BRACELET. One bracelet even had the hand of Fatima beside the apotropaic blue “eye bead”. (left) The eye-bead design goes back millennia.

Whether you believe in the “evil eye” or not, staring faces or eyes obviously have as powerful an effect on our subconscious today as they did in Roman times.

For more information about Caroline Lawrence’s history-mystery books for children, including The Sewer Demon, visit her author page or website.

June 13, 2013

‘All Manner of Optick Glasses After the Latest Manner’

The early 1700s saw the emergence of daily newspapers for the man on his way to work, or sitting in the coffee house. Just as now, a significant percentage of the population suffered with imperfect sight. Spectacles and magnifiers of all sorts had been available for two centuries, but it was the advent of the newspaper which saw them really take off.

Spectacle-makers produced huge ranges of tortoiseshell, horn and whalebone (super-flexible and hard to break) as well as silver. They could be purchased off-the-shelf with the prescription or ‘focus’ written on the arm, or made-to-measure. Edward Scarlett of Soho, working in the 1730s, was the most famous of the early makers, with his spectacles being marketed as having ‘the Exactest way of fitting different Eyes’. He popularised arms on spectacles (usually of the pince-nez type before) and catered for different activities such as reading or sewing. The picture here is his trade card.

The bifocal lens was invented in the 1760s, but by whom it is impossible to say. Benjamin Franklin is commonly cited as the culprit, but that’s most likely just a nice myth. They were first used for artists who could look at their subject through the top and their canvas through the bottom, but they soon became common amongst clerks, academics and scholars who didn’t want to be putting them on and off all the time.

Later on in the century, green and blue lenses started to appear. The idea came from Venice, where they were apparently used to deflect the sun reflecting from the lagoon, but the Venetians were expert glass-workers and it is possible they already had a medical use. In England they may even have been used as filter for dyslexia sufferers, as they are also seen in lenses with a ‘reading focus’.

To get fitted for spectacles, it was usual to go to one of the many little ‘Optickal’ shops in and around Soho and the City. There spectacles could be tried out, and fashionable frames chosen. The widespread availability of spectacles and their common use is clear by the inventory of Nathaniel Adams of Charing Cross in 1741: he died with 499 pairs of ready-made spectacles in stock, ranging from the cheapest horn frames at little more than a few pence, to silver ones at a shilling each. Of all of the shops in Georgian London, I would love to get a peep inside Scarlett’s emporium (or Adams’s, who was Scarlett’s apprentice).

June 9, 2013

Should physicians treat their enemies?

There are a lot of mistaken ideas about the ‘Hippocratic oath’; for example, that it was written by the real Hippocrates (deeply unlikely – probably written way after his supposed lifetime); that it bans abortion (no, it bans giving an abortive pessary to someone asking for one, so other methods could be fine, and maybe the issue here is instead that the physician should not hand over drugs to someone who may use them a long way away from proper medical supervision); that it forbids assisted suicide (no, it says you must not give a deadly drug to anyone if asked for one, which may again be about keeping control of dangerous drugs rather than handing them out); and so on. With all this concern about drugs, we do well to remember that the ancient Greek word pharmakon means both ‘healing drug’ and ‘poison’!

There are also assumptions about clauses that people think are in there, but which aren’t. Like ‘first do no harm’, which is from another ‘Hippocratic’ treatise, not this one. And all sorts of notions about the ethics of an ancient Greek physician which are not even touched upon in the oath. One of these is the reassuring idea that a good doctor will treat anyone, no matter what their race, nation or creed may be. But that’s not an ancient idea either. In fact, quite the contrary. Here’s a story that was told about Hippocrates:

Once a terrible plague was ravaging Persia, the historic enemy of the Greeks. The king of Persia, Artaxerxes, had heard that Hippocrates was the most brilliant physician in the world, so he sent an embassy to see him. When they arrived the king’s men begged him to come and help. They offered him all the silver and gold he could possibly want. But Hippocrates shook his head and said, ‘No. I have enough food, clothing, shelter and everything else I need for life, and I don’t want all that Persian opulence. I will not help those who are the enemies of the Greeks’.

In the ancient world, patriotism beat mercy hands-down.

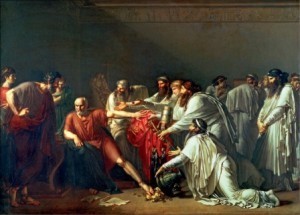

In 1792, the artist Girodet painted the scene in which Hippocrates refuses the gifts of the king. The various Persians around Hippocrates show different expressions as the great doctor refuses to help them: angry, amazed, sad… Meanwhile Hippocrates’ foot is pushing away the pile of money on the floor. At the time this painting was done, Hippocrates’ patriotism and his disdain for wealth were right up there with his ‘scientific’ medicine as what made him so great.

What do you think? Should doctors treat anyone, regardless?

June 8, 2013

The Ordeal of Opal Petty

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

When Opal Petty died at the age of 86, her family buried her with a half-dozen dolls she had treasured during five decades of her life. That was the stretch in which the Texas state hospital system confined her without apparent reason, gave her no treatment for her supposed mental illness, and left her with a disorder that resulted from her custodial care. Rescued from hospitals by relatives she had not previously known, Petty launched an influential legal challenge to the state’s commitment practices.

The entrance to Austin State Hospital, where Opal Petty was confined for decades.

Her troubles began when she reached her teenage years in the small town of Goldthwaite, Texas. Her family disapproved of her wish to date, dance, and go out. Petty broke down in a psychotic episode and began digging her own grave in the family’s yard. Local preachers could not help her, so her parents sent Petty to Austin State Hospital in 1934.

There the 16-year-old was diagnosed with schizophrenia, but later examinations, when her behavioral problems had ended, adjusted her diagnosis to mental retardation, no mental retardation, and no mental illness. Petty received no treatment and spent her days collecting dolls and working in the hospital laundry, where she earned two dollars per week.

Thirty-seven years after her arrival in Austin, hospital authorities transferred Petty to an institution for the mentally disabled, the San Angelo State School in Carlsbad. She remained there until the mid-1980s, when her life suddenly changed. At a family reunion nearby, Linda Kauffman, a family member by marriage, heard about Petty for the first time. Kauffman checked at San Angelo and confirmed that Petty, now well into middle age, was confined there. Kauffman and her husband, Petty’s nephew, began visiting her. Petty wore what Kauffman called “a burlap sack” the first time they met, and a nurse revealed that the patient had not spoken for several years.

Kauffman engaged a lawyer and began a legal battle to free Petty from institutional care. The state released Petty to a foster home and in 1986 let her move in with Kauffman and her husband. Three years later, a Texas court awarded Petty damages of $250,000 for her improper confinement and the resulting mental deprivation, and the Texas Supreme Court approved that decision in 1992. Her lawyer argued that she should have been released from the hospital within weeks of her initial episode, when her psychotic symptoms ended. Texas changed its hospital commitment policies to give patients annual reviews of their treatment and status.

Petty spent the rest of her life with her newfound relatives. She enjoyed playing the piano and taking in the new sight of fresh fruits and vegetables in the supermarket. She died in 2005.

Further reading:

Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher. “Opal Petty, 86, Patient Held 51 Years Involuntarily in Texas, Dies.” The New York Times, March 17, 2005.

Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation v. Opal Petty. Decision by Court of Appeals, Third District of Texas, August 28, 1991.

June 6, 2013

Who Were the First Recreational Mountain Climbers?

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

(Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Moses climbed Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments and ascended Mount Nebo (Jordan) to gaze on the land he would never reach. Jesus took three disciples to a mountaintop to commune with the ghosts of Moses and Elijah. Empedocles, the ancient Greek philosopher, climbed the active volcano Mount Etna on Sicily and leaped into the flaming crater in 430 BC. According to legend, he intended to become an immortal god; the volcano ejected one of his sandals turned to bronze by the heat.

But these religiously motivated peak experiences cannot be described as enjoyable or recreational.

For what may be the earliest summit experience undertaken for pleasure we can look to the ancient Roman historian Livy. King Philip V of Macedon’s mountain climbing expedition was undertaken to admire the spectacular view from Mount Haemus in Thrace, a high peak (ca 7,000 ft) in the Balkan Mountain Range of Bulgaria. In antiquity, it was a popular belief that one could see two different seas—the Adriatic and the Black— from the peak. Philip, recently retired from ruling his kingdom (involuntarily, due to the Roman conquest of Macedon in 197 BC) was keen to see this celebrated panorama. According to Livy, as Philip and his men “approached the summit everything was so covered with fog that they were slowed down just as if they were on a night march.” When Philip’s party descended, however, the Macedonian mountain climbers “said nothing to contradict the general notion of the fabulous view of oceans, mountains and rivers that one could view from the peak.” (On a clear day one might see the Black and Aegean seas, but not the Adriatic.) Livy rather nastily insinuates that Philip and his friends hoped “to prevent their futile expedition from providing material for mirth.” Livy and the Romans doubted the recreational nature of Philip’s expedition. They suspected that his goal was military reconnaissance, part of a strategy to make war on Rome.

Another ancient instance of recreational mountain climbing occurred in AD 126. The Roman Emperor Hadrian had heard that sunrise over Mediterranean from Mount Etna was breathtakingly beautiful. The emperor’s team ascended Mount Etna and arose at dawn to admire the sun’s multicolored rays like a rainbow as it rose over the sea. The iridescent effect would have been due to the volcanic smoke, scintillae, and particulate matter in the atmosphere. I’ve never climbed Mount Etna for sunrise but I imagine it might even surpass the spectacular sunsets to be observed today in Elizabeth, New Jersey, thanks to the smoke and flames belching from the oil refineries there.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

May 30, 2013

The Art of Beagling in Eighteenth-Century England

Snoopy, the world’s most famous beagle, epitomizes several of the breed’s traits: the dangly ears, the prominent snout, the fixation on food. But in the cartoon, he retreats regularly to an imaginary world of adventures to escape the monotony of a dog’s life. An eighteenth-century beagle’s life would, perhaps, have been of more interest to him—the confinement of kennel-life interspersed with the thrill of the hunt. Beagles became an established hunting breed in the fifteenth century and, by the early eighteenth century, there was much information on how to build the best beagle hunting pack.

An illustration of the Southern Hound. From J.H. Walsh, The dog, in health and disease, by Stonehenge (1859). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The breed that we know and (in my case) love today was very different in early modern England. The term beagle was used until the eighteenth century to describe several sorts of hounds, including the harrier.[1] The smallest of the hounds, beagles were used primarily for chasing hares and were known for their “exquisite smell” and perseverance.[2] By the eighteenth century, there were three main types of beagle, outlined in 1788 by Cynegetica or essays on sporting consisting of observations on hare hunting &c. The wire-haired Northern Beagle was small (about 12 inches), fast, impetuous and cheerful, doing “his business as furiously as Jehu himself can wish him”. The smooth-haired Southern Beagle was larger, rangier, phlegmatic, slower and patient. A third type of beagle was a small lapdog, which—according to The Sportsman’s Dictionary (vol. 1, 1705)—makes a pretty diversion in hunting the coney”, but was otherwise not serviceable.

Building “a neat Pack [was] somewhat difficult”, advised James Lambert in 1710 (The Countryman’s Treasure). Lambert specified that the hounds should be well-matched with each other or “one will hinder another”. Cynegetica and other books recommended that the owner breed the Northern and Southern types together, with the goal of producing offspring that would keep the tenacious scent-tracking of the Southern with a little of the Northern’s speed. The Sportsman’s Dictionary suggested that, when crossed, they would make “great killers”. Lambert added to this that there should be two “Hunts on the Highway” to follow scent on hard ground and “two old staunch Hounds” to moderate the “over-swiftness of the younger and unexperienced”.

The owner should also take care to match the pack to his own temperament; the slowness of the Southern Beagle, say, might prove “trifling and tedious” to a man who preferred speed (Cynegetica). Particular care should also be taken in the musicality of the pack, for as Ralph Beilby described, beagle “tones are soft and musical, and add greatly to the pleasures of the chase”. Lambert gave thought as to how the pack owner might achieve “better Harmony”: “some whiners and Treble-cryers are necessary”. A well-balanced pack of twenty beagles would be most efficient and provide the most pleasure in the hunt.

There was also much advice on the care of the pack, from conception to diet. The hunting dogs were, perhaps, afforded better care than many people in early modern society. Nicholas Cox wrote that the female should be strong and well-proportioned, while the sire should be young. An old sire would result in “dull and heavy whelps”. A pregnant female should be allowed free range of the house and fed hot broth daily (The huntsman, 1780). Suitable hound names, as listed by Cox, included noble titles (Younker, Countess, Cesar, Duke), flowers (Lily, Tulip), mythological (Daphne, Hector, Dido, Juno), sounds (Music, Ranter, Thunder, Tatler) or personality (Fuddle, Wanton, Plunder, Merry-boy, Jolly-boy)…

Around the age of one, a dog could be introduced to the pack and would benefit, at first, from “the smack of the whip” (The gentleman farrier, 1732). Lambert outlined the pack’s daily care routine. Kennels should be dry, warm and vermin-free, with a supply of clear water and daily sun. The dogs should also have access to a “chimney-fire in cold damp weather” where they could cool down after a hunt. This would prevent diseases like mange, itch and fever, which were thought to be caused by sudden changes in bodily temperature. Their food was to be given throughout the day and included broth with crusts, table scraps and whey and milk with bran.

There was an art to beagling, which entailed close attention to hound care, breeding and pack harmony. The descriptions of an ideal pack reflected wider social ideals of obedience, stability, mastery and efficiency, as well as highlighted the quality of life gap between the poor in society and their squires’ dogs. By 1800, Sydenham Edwards claimed that it was rare to see a full pack of beagles any more. Instead, the beagles were kept primarily as finders to greyhounds in coursing. As huntsmen turned their attention from hares to foxes, beagling fell out of fashion and, over the nineteenth century, a more modern beagle was born. But one thing remains constant, as Snoopy’s pursuit of the Red Baron shows: dogged perseverance.

[1] Sydenham Edwards, Cynographia Britannica (London, 1800).

[2] Ralph Beilby, A general history of quadrupeds (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1790).

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800), as well as teaches a course on “Defining Boundaries: Natural and Supernatural Worlds in Early Modern Europe”. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. Follow her on Twitter, where she tweets as @historybeagle.

May 20, 2013

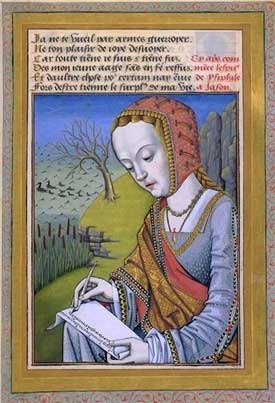

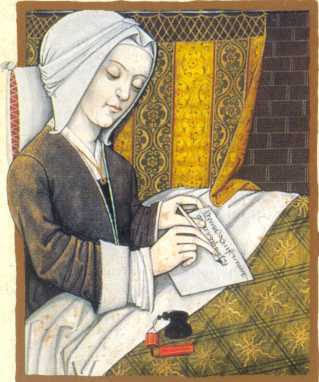

Reading Women, and Reading Women

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

That is, reading women (the act of reading works written by women) and reading women (women who read).

When I received a grant from the NEH to study texts about women written by women in the Middle Ages, many of my friends were puzzled that this was possible. “Medieval women were literate?” Well, yes—and some of them produced among the most interesting texts of the period.

When I received a grant from the NEH to study texts about women written by women in the Middle Ages, many of my friends were puzzled that this was possible. “Medieval women were literate?” Well, yes—and some of them produced among the most interesting texts of the period.

Depending on the time, the definition of literacy (reading and writing, or just reading? Latin and the vernacular, or just one?), and the geographical region, estimates of female literacy in the Middle Ages vary between 1% and 50% (the ability to read and write in Latin produces the lowest figure). Members of the upper class of both sexes made up the vast majority of the literate, no matter what the definition, and there’s little reason to believe that more medieval men than women were literate in the vernacular.

Some scholars have credited women with spurring the growth of vernacular literature at the end of the Middle Ages, for several reasons. Perhaps the most important is that since women were largely unable to read Latin, love-poetry addressed to them had to be written in the vernacular, or the verse wouldn’t have its desired effect.

The growth of universities in the thirteenth century, usually heralded as a new burst of knowledge in Europe, actually led to the lowering of expectations for women. Now that the possibility of higher education was open to boys, families of the lesser nobility and merchant classes tended to neglect their daughters’ instruction in order to prepare their sons for this opportunity.

Women were not, however, always excluded from universities. Records refer to women teaching “law, philosophy, rhetoric and medicine at Bologna and other Italian universities in the thirteenth centuries. . . . But it is fairly certain that even in Italy, universities provided women with neither a formal education nor a license to teach.”1 One instructor named Novella reportedly had to lecture to her classes at the university of Bologna from behind a screen, so as not to distract her students with her beauty.

Northern Europe proved, in general, to be more hospitable to female literacy than the south. Barbarians thought letters unmanly, even (or especially) for rulers. The Gothic Queen Amalasuintha (c. 494-535) “wanted to mold [her son] Athalaric on the pattern of a Roman ruler, and engaged tutors to oversee his education. Her plan was thwarted by the Goths’ conviction that literary pursuit was unmanly. Enforced study drove a youth to cower before his teachers–old men at that. . . . The noble advisers . . . summoned evidence that Theodoric had looked unfavorably on the enfeebling effects of book learning.”2

The husband of St. Margaret of Scotland, King Malcolm, admired his wife’s ability to read. Charlemagne was probably illiterate while at least one of his wives was probably literate, and his daughter Bertha wrote a lengthy history, Historiarum libri quator. William the Conqueror’s wife, Matilda of Flanders, was better educated than her husband. Hugh of Fleury dedicated his Historia ecclesiastica to Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror, rather than to “illiterate princes who scorn the art of literature.”3

Perversely, women’s very exclusion from writing helped them to compose some of the most interesting medieval texts. In most cases there was no fixed definition of what women could write–no “canon.” With few exceptions, they did not confront a long publishing tradition and try to break into it. Much of their writing thus seems to the tastes of many modern readers fresher, more original, and often more interesting than that of their male contemporaries.

1Phyllis Stock. Better than Rubies: A History of Women’s Education. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Capricorn Books, 1978, p. 25.

2Karen Cherewatuk and Ulrike Wiethaus, eds. Dear Sister: Medieval Women and the Epistolary Genre. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993, p. 75.

3Alexandra Barratt, ed. Women’s Writing in Middle English. London and New York: Longman, 1992, pp. 76-77.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

May 18, 2013

Stranger Magic

by Pamela Toler

I’m fascinated by the Arabian Nights. By the stories themselves and the way they fit together into their complicated frame story. By their transformation from Arabic street tales to a established position in the Western canon. By their echoes in Western culture, from the Romantic poets to Disney.

So I was delighted to get a chance to review historian and critic Marina Warner’s new work on the tales.

Warner’s Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights is a multi-faceted study of the popular tales of wonder and magic known as the Arabian Nights.

Warner discusses the tales in the Arabian Nights with the interdisciplinary approach that she used to good effect in her earlier study of Western fairy tales, From the Beast to the Blonde. She examines them through the lenses of literary criticism, history, folklore studies, feminist theory and popular culture. She pays particular attention to the history of the Arabian Nights in the west, from the reception of the first translation from the Arabic by Antoine Galland in the eighteenth century through its influence in works as distinct as Mozart’s operas and the Harry Potter books.

Not assuming that readers will have the same familiarity with “The Prince of the Black Islands” as they do with “Sleeping Beauty”, Warner retells fifteen tales before she unravels them into their constituent themes, symbols and assumptions. She moves easily from the Biblical story of King Solomon to magic carpets, from the reputation of Egypt as the home of ancient magic to Sir Isaac Newton’s alchemical experiments, and from the wealth of the Islamic world in the twelve century to post-Reformation anxiety about Catholic religious practices.

Warner succeeds once again in balancing entertainment with erudition. Like her earlier works, Stranger Magic is accessible enough for the general reader and rich enough to keep a specialist scribbling in the margins.

This review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.