Holly Tucker's Blog, page 69

March 9, 2013

Julia Pastrana, ‘bearded lady’

by Helen King

Lucy Inglis recently posted on the ‘Hottentot Venus’. Last month, there was a big day for the ‘bearded lady’: Julia Pastrana’s body was repatriated to her native Mexico and buried, her coffin covered with white roses. Julia, ‘the world’s ugliest woman’, suffered from excessive hair growth on her face. She was exhibited at freak shows by her impresario husband in the 1850s and, after her death in 1860, he went on travelling with her embalmed body, displayed so that audiences could now gaze at her without the embarrassment of her returning their stares. Rebecca Stern has listed the many parallels between Julia and the character Marian Halcombe in Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White, which was serialised in 1859-60. For example, we are told that Halcombe’s ‘complexion was almost swarthy, and the dark down on her upper lip was almost a moustache’, and that the viewer is ‘almost repelled by the masculine form and masculine look of the features in which the perfectly shaped figure ended’.

Julia was by no means the first such woman to be displayed. In the Renaissance, the three Gonzales ‘hairy girls’ were moved around the courts of Europe during the sixteenth century, like living items in a cabinet of curiosities. But it was in the mid-nineteenth century that the ‘bearded lady’ became a staple of the live freak show. The rise of the railway and the steam ship in the 1830s enabled such shows to take off, with performers being able to travel not just within one country, but also between nations. Nadja Durbach argued that the peak of their popularity came at a time of ‘modern and imperial self-fashioning’. Why ‘modern’? Because, scholars argue, the display of the ‘weird’ is part of modernity’s attempts to restrict the possibilities for individual variation. Not just the paying public, but also medical professionals, were interested in these variations.

While some such ‘women’ may have been men dressed in women’s clothing, many were not. Those displayed included people of uncertain sex – such as Gottlieb Göttlich, who travelled over Europe as medical experts failed to decide on the ‘true sex’ – as well women with various hormonal or genetic conditions who grew beards or were hairy all over. The ‘bearded lady’ was often shown smartly dressed, looking like a respectable woman of the time. This made the beard even more of a shock. Those with hair all over were shown in skimpy clothing and displayed as the ‘missing link’ with the animal kingdom; for example, both photographs and posters survive showing a woman who was exhibited from 1883 as ‘Krao’, and the posters were drawn to make her more hairy than she really was.

Were these people exploited, tragic figures, or were they in control and finding a way to make a living? Was this a career – or a form of slavery? Krao’s display coincided with the move for women’s rights in education and politics, making the ‘bearded lady’ a particularly worrying figure. In one cartoon of the period, a suffragette asks the bearded lady on display in a shop window ‘How did you manage it?’ The bearded lady has her travelling bag beside her; this shows that, in some ways, it is she rather than the suffragette who has the greater freedom.

To find out more:

Nadja Durbach, Spectacle of Deformity. Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2010.

Rebecca Stern, ‘Our bear women, ourselves. Affiliating with Julia Pastrana’ in Marlene Tromp (ed.), Victorian Freaks. The Social Context of Freakery in Britain, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2008, 200-233.

Merry Wiesner-Hanks, The Marvellous Hairy Girls, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

March 8, 2013

The Black Stork: A physician’s cinematic argument for eugenics

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

A scene from The Black Stork (1917)

One of the most infamous movies of the silent era, which made a case for allowing disabled infants to die, sparked a national debate between 1917 and the late 1920s before sinking into obscurity. Along the way, The Black Stork rocketed a physician to fame and symbolized America’s conflicted attitude toward eugenics and the value of human life.

The story of The Black Stork begins with the involvement of Chicago surgeon Harry J. Haiselden in the treatment of a severely disabled newborn, a boy apparently never given a first name but surnamed Bollinger, in 1915. The baby’s deformities, Haiselden warned the parents, would lead to a life of imbecility, misery, and crime if the child survived. The parents accepted Haiselden’s recommendation to withhold medical care and allow the infant to die.

The surgeon, a graduate of the University of Illinois College of Medicine, then took the unusual step of calling a press conference to announce his holding back of treatment to the baby Bollinger and his intent to campaign for the deaths of similarly disabled infants in the future. These children, he believed, endangered the genetic well-being of the nation, and if allowed to live they would bring despair to themselves and their families. Haiselden’s declaration sat well with devotees of eugenics and theories of the hereditary passage of criminal and antisocial traits, and he received support from the famed social activist Helen Keller. The doctor determined to extend the resulting firestorm of discussion and criticism by promoting his cause in the production of a feature-length motion picture.

Haiselden himself took the starring role in The Black Stork, which tells a story similar to that of the Bollingers. A mother gives birth to a child with congenital syphilis, contracted from the father’s “tainted blood.” The baby is mentally and physically disabled, and the parents follow the advice of their doctor (played by Haiselden) to let it die out of mercy and to protect society from having to tolerate an unhappy misfit in its midst. Promoters advertised the film as a “eugenic love story.”

The movie boasted impressive credits. Leopold and Theodore Wharton, who managed the famed melodramatic 1914 serial The Perils of Pauline, handled production, and Jack Lait, a celebrated muckraking reporter for the Chicago Herald, wrote the photoplay.

Starting with early screenings for the Ohio state legislature and at movie palaces in Chicago and New York, The Black Stork was shown across the nation, often in tandem with lectures by Haiselden. Local censors frequently demanded cuts or changes.

Haiselden eventually participated in the deaths of at least three more disabled infants, sometimes accelerating the fatal result, before he suddenly expired from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1919. But The Black Stork lived on. In 1927, it was reedited into a new film with an even stronger eugenics message, titled Are You Fit to Marry? Eventually the film descended into distribution through touring road shows that specialized in presenting sensationalized entertainment. After the 1940s it vanished from view for decades until University of Michigan researcher and professor Martin Pernick tracked down the last viewable print of Are You Fit to Marry? and wrote a fascinating book that chronicles Haiselden’s career and influence.

Sources:

Cheyfitz, Kirk. “Who Decides? The Connecting Thread of Euthanasia, Eugenics, and Doctor-Assisted Suicide.” Omega, Vol. 40(1) 5-16, 1999-2000.

Pernick, Martin S. The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of “Defective” Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures. Oxford University Press, 1999.

“Surgeon Lets Baby, Born to Idiocy, Die.” The New York Times, July 25, 1917.

March 6, 2013

Flying Snakes in Ancient Egypt?

image by Jeff T. Owens

(Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Egyptian tales of flying snakes captured the curiosity of the Greek historian Herodotus (ca 460 BC). These winged drakontes were said to live under frankincense (Boswellia) trees in the Arabian Desert. To gather the incense, the Arabians burned styrax (resin of the Liquidambar tree) because the smoke drove the winged snakes away. Herodotus described the flying reptiles as small with variegated markings, shaped like a water snake but with wing like membranes, like bat wings.

The Arabs told Herodotus that these creatures would be a plague upon the earth except for two reasons. In the first place, the violence of their reproductive life ensures that their population remains small. Not only does the female kill the male during mating by “biting clean through his neck,” but the females give birth to live young instead of laying eggs like other serpents—and these young are so vicious that “they are born by eating their way out of the womb thus killing their mother.” The other reason was that when winged snakes fly east from the desert toward Egypt in spring, they travel through a mountain pass where “ibis birds” gobble them up. “Entirely jet black with legs like a crane and a very hooked beak,” these birds, adds Herodotus helpfully, “are the size of a Greek krex” (if only we knew what a krex was!)

“I went to try to get more information about the flying snakes,” says Herodotus. In the vicinity of “Boutos” in Arabia he was shown “narrow mountain pass leading to a broad plain which joins the plain of Egypt.” There he marveled at the “heaps of skeletons and spines in incalculable numbers; some skeletons were large, others smaller, and others smaller still.”

These passages are among the most cryptic in Herodotus (2.75, 3.107-8). Classicists, natural historians, and cryptozoologists have long puzzled over what Herodotus saw and where he saw it. Were there any germs of truth in his account of the Egyptian lore?

At least we can identify Boutos, an ancient city on the eastern Nile Delta at the edge of the Arabian Desert (Sinai Peninsula) and make a good guess at the bird. In antiquity, the black Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) frequented the brackish Bitter Lakes region of dry salt valleys between Egypt and Sinai (now the Suez Canal). A more likely candidate would be an extinct relative of the now nearly extinct Waldrapp (Geronticus) northern bald ibis. These migratory black desert ibises were once widespread across North Africa and the Middle East, breeding on cliffs in arid habitats rather than wetlands like their cousins. Ibises fed on insects and reptiles.

What about the winged snakes? Was the lore based on legendary hordes of large flying insects, perhaps locusts, preyed on by huge flocks of birds? Was there once a population of “parachuting” lizards or “gliding” snakes in the Sinai? (Draco volans and Chrysopelia, respectively, are now only found in southeast Asia). Note that Herodotus was never shown live specimens, only heaps of jumbled bones of different sizes. Could the Egyptian tales have arisen to explain mysterious fossil deposits of spinosaurid dinosaurs (with a membrane “sail”), or a large mixed deposit of fossil birds and reptiles eroding out of a salt valley now obliterated by the Suez Canal? The true identity of the winged snakes of ancient Arabia remain a tantalizing unsolved enigma.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 2, 2013

Ruby Stars

By Eric Laursen (W&M Contributor)

Silver Stars and Tsarist Eagles

In 1935 the tsarist eagles that once perched atop the five towers of the Moscow Kremlin were replaced with massive revolving silver stars cut out of metal, with the design of a hammer and sickle made from semi-precious stones mined in the Urals (around 7000 stones were used in total). The stars were built in the prop department of the Bolshoi theater, a fact that signals the theatricality of this act of dressing the stage of power. Before being installed, several of the new stars were displayed at ground level next to the metal tsarist eagles that had been removed to make way for them. A Pravda correspondent declared enthusiastically: “A striking spectacle! On one side–the brilliant embodiment of our finest contemporary technology, our astounding culture of labor, the high skill of our collective; on the other side–rusted iron birds, shoddily made, riveted crudely and primitively, like samovar pipes.” As in many of the images of Soviet enlightenment, the stars are presented as a marvel of the “finest contemporary technology“ and socialist labor, which hones “the high skill of our collective” to the point where they can produce craftsmanship that is far superior–both in aesthetics and in construction–to those made by workers exploited by the aristocracy. The tsarist “birds” were “shoddily made,” never meant to last and therefore rusted by the processes of time. The eagles are compared to samovars, a technology connected with the Russian countryside–not the progressive city–and powered for generations by burning coal, “crudely and primitively.” Compare these aging rusty eagles to the silver stars that revolved because of electricity and were illuminated at night by electric light. The silver and stone stars were presented as shining tributes to the Soviet ability to rework mother nature, to take semiprecious stones and metal from the ground and mold them into the stage props of a grand “spectacle,” massive pieces of costume jewelry designed exclusively for the Soviet staging of power.

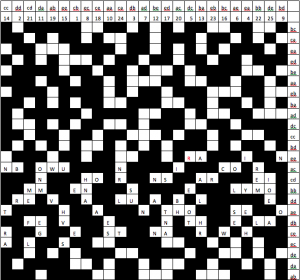

Kremlin Star

The silver stars, “the brilliant embodiment of our finest contemporary technology” soon lost their luster due to Moscow pollution. The red glass and metal stars that are usually referred to as “ruby” stars took their place, minus the hammer and sickle, a deletion that Julia Bekman Chadaga sees as evoking the politics of 1937: “There was thus a shift in emphasis away from the human labor involved; now all eyes were on the light source that stood for ‘Soviet power,’ more specifically, the charismatic power of Stalin, the deity in the Kremlin.” It would be just as easy, however, to read the change as one from hand-craftsmanship–semi-precious stones mounted by Soviet artisans–to factory produced artifice, a mark of Soviet industrialism. In the ruby stars the rough elements produced by nature–sand and metal–had been transformed by Soviet industry into a substance that nature could not produce by itself. The ruby stars resist the weather and yet retain brilliance, by day from three sheets of layered glass–white and red with a clear sheet sandwiched in between to aid in reflectivity of sunlight–and by night from a system of mirrors and light bulbs installed in their base. Rather than needing external illumination, these stars echo the stars above them by producing their own light from within, and due to the layering of glass are able to shine both by day and by night.

Soviet New Years Card

These enormous stars—the largest of which is twelve feet across–were installed in September and October of 1937, just in time for the 20th anniversary of the revolution. The Kremlin Stars were attributed with the same powers always given to the red star–a force of good fighting the forces of darkness, but now connected to the 800-year history of the Kremlin, a seat of political power for pre-Petrine Russia and the Soviet Union (with Petersburg taking the stage for over two centuries in between). Therefore the mounting of the red stars on the ancient Kremlin constituted a reclaiming of Russia’s history for the Soviet Union. By having the stars powered by electricity the installation also became a symbol of the rejuvenation of this traditional power. A 1938 song by Vasilii Lebedev-Kumach depicts Moscow “bravely conquering all powers of darkness [sily mraka], lit up by the blaze of scarlet stars, eight centuries old but eternally young.”

An Old Doctor, a Convent Apothecary, and an Eighteenth-Century Medical Dispute

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

In December 1718, Dr. Tolozé, who styled himself an ‘Ancien Medecin’ (Old Doctor), wrote to physician Étienne-François Geoffroy.[1] Tolozé wanted Geoffroy to settle a dispute between him and the nuns of St. Eutrope near Chartres. Geoffroy, he believed, was well-placed to help, being the doctor of a Mme Cossins who had two daughters in the convent. This was of particular interest to Tolozé since one of Mme Cossins’ daughters was the convent apothecary.

A doctor instructs his English patient not to eat as he does.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Tolozé insisted that the nuns had been nothing but trouble since he had taken over as the convent physician four years previously. In part, he suggested, the problems stemmed from the previous doctor’s care. The last doctor had disliked blood-letting and instead encouraged the use of wine and cordials in his treatments. Tolozé preferred to prescribe tisanes, proclaiming liquor “hardly suitable.”

But the issue of blood-letting was at the heart of the dispute. Tolozé complained:

I find that these religious Ladies have much repugnance to bleeding, and above all the aforementioned Dame apotiquairesse who stands in the way of it very often and at just the wrong moment, to this Evacuation and to other remedies that she hardly knows.

To make matters worse, the nuns were increasingly resistant to being bled, following the recent deaths of three elderly nuns—including the Mother Superior: “These Ladies by an Error and a badly founded suspicion dared to attribute the death of their mothers to the bleeding.”

Tolozé believed that the real problem was that the patients had not been bled sufficiently to cure their chest ailments. He asked for Geoffroy’s advice in reviewing these cases, including the question of the usefulness of blood-letting and the “damnable” use of wine in treating chest ailments. Tolozé noted that the nuns believed wine was helpful: the “reason is that it fortifies.” He continued, though, “it is certain that one has advanced the death of all these nuns by this liqueur.”

The case had made him doubt his ability to manage the health of the nuns of St. Eutrope successfully. As he wrote:

If there is a doctor who is mortified it is me Monsieur, who has an Experience of thirty years. I protested to them that I would write to Paris today . . .. I beg you to give me this grace, and to make known to these good Ladies that they are making a very dangerous error. They have forgotten that in 1696 there were ten nuns who died in a short period when they were not bled because their ordinary doctor did not know the importance of this healthful and efficacious evacuation.

Tolozé had two major grievances, the dismissal of his medical skills and being blamed for killing three patients. Where he thought Geoffroy might help, though, was in persuading the convent apothecary to stop opposing his medical advice. The dispute was perhaps not so much a matter of female apothecary against male physician as a case of both physician and apothecary claiming the role of expert. Tolozé may have been an ‘Ancien Medecin’, but the apothecary had her own experience, which had not been contested by the previous physician whose remedies she continued to use.

Tolozé also wanted help in managing his unruly patients, but revealed his low tolerance for anything that deviated from his demands. When it came to wine, for example, “they say they take only a little. I retort to them that a little is always harmful.” But refusal to comply with his demands made sense to the nuns; since at least 1696, they had followed a very different regimen to the one prescribed by Tolozé. And who wouldn’t prefer to drink a bit of wine and avoid bleeding?

I have no idea what Geoffroy’s reply was. However, what Tolozé didn’t seem to understand was that he was demanding that the nuns alter ther whole understanding of health—a big ask after only four years of treating them! For Tolozé, the uncooperative patients undermined his authority; for his patients, his thirty years of experience did not automatically make him the expert.

[1] Bibiliothèque Interuniversitaire de Santé, Paris, MS 5244, ff. 216-217.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800). She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. She tweets as @historybeagle.

Dancing Girl

I discovered this dancing girl today while I was researching the history of Indian midwives. She has absolutely nothing to do with Indian midwives, but blind alleys are part of the pleasures of research, and isn’t she gorgeous?

I discovered this dancing girl today while I was researching the history of Indian midwives. She has absolutely nothing to do with Indian midwives, but blind alleys are part of the pleasures of research, and isn’t she gorgeous?

She is 4,500 years old and was found, in 1926, in the red rubble of Mohenjo- daro, an archeological site in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. She is 10.3 cm (4.3”) high, and there’s something splendidly and archetypically teeny and like I should give a damn about her posture.

In 1973, archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler was similarly smitten by her:

‘pouting lips and insolent look in the eyes. She is about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there, with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There is nothing like her, I think in the world.’

Reading further, I discovered that the dancing girl, for all her impious nakedness, lived in one of the most advanced urban settlements in the world, Mohenjo- daro, built around 2600BCE and abandoned in the 19th Century BCE, (population around 35,000) not only produced the most exquisitely crafted jewelry, gold artifacts and sculptures, but had a drainage and re-cycling system that many modern cities today would envy.

Our tiny dancer would, most likely, have lived in a house of mortared brick in a city organized around a market place, and, as she sashayed down the road for rehearsal or performance, she would have passed streets lined with covered brick sewage channels, with manhole covers at intervals for clearing them.

I think she would be no stranger to the bath. If she was poor, she would have used a public bath designed to house 5,000 citizens, and if parents were well off, inside their house sewage would have flowed from the bathroom via earthenware pipes into a system shrewdly organized so that rain water and sewage from the houses did not flow into the street, but were channeled into separate and carefully situated sump or cess-pits. When the cess-pit was three quarters full, the water disappeared down main drains which emptied into soak pits away from the town.

Hard to imagine this girl as a dab hand with the housework, but her women and servants of Mohenjo- daro would have had the benefit of neat design in their kitchens too. In Mohenjo- daro, garbage was taken through chutes built into houses, and went straight into brick bins outside, which makes our British recycling (pink plastic bags for paper, purple for tins), thought up by some bright spark 4,500 years later, look distinctly retrograde.

This, remarkable concern for sanitation apparently, made it the cleanest city in the prehistoric world, and one of the best protected.

I doubt our dancer would have been allowed out unescorted, but if she was, she would, as she bounced and skipped her way along the streets, have been well protected by numerous police check points, situated in small kiosks on the corners of major thoroughfares, and beyond that, a city well fortified by guard towers all around it.

I enjoyed my side trip to Mohenjo- daro; nice place to grow up, it sounds.

It made me want to know what happened to her next: how she trained; how she courted, got married, had babies, which brings me back to my original task of finding the village midwife. I’ll update you on this when I find her.

February 23, 2013

The Zodiac Ciphers: Messages from a Murderer

by Neil Sareen (Vanderbilt University)

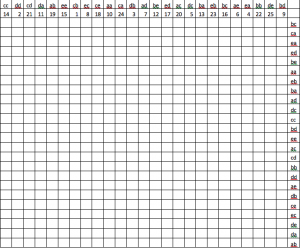

The 1960s of the Bay Area of California are often remembered as a time of love and social expansion, but there remains a terrible and unexplained stain on the otherwise illustrious history. A lone and extremely elusive killer wandered the Bay Area streets at night. Known as the Zodiac killer, because of his messages signed with a zodiac symbol, he became one of the most infamous and terrifying killers in history. While he claimed to be responsible for the killings of 37 people, investigators were only able to confirm only seven victims (five were murdered, two survived). Throughout his serial killings, the Zodiac killer would write letters to the Bay Area press in an attempt to brag and taunt his pursuing officers. But these weren’t any ordinary letters. They were ciphers. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s the Zodiac killer sent four coded letters. Of the four ciphers, only one has actually been solved.

The 1960s of the Bay Area of California are often remembered as a time of love and social expansion, but there remains a terrible and unexplained stain on the otherwise illustrious history. A lone and extremely elusive killer wandered the Bay Area streets at night. Known as the Zodiac killer, because of his messages signed with a zodiac symbol, he became one of the most infamous and terrifying killers in history. While he claimed to be responsible for the killings of 37 people, investigators were only able to confirm only seven victims (five were murdered, two survived). Throughout his serial killings, the Zodiac killer would write letters to the Bay Area press in an attempt to brag and taunt his pursuing officers. But these weren’t any ordinary letters. They were ciphers. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s the Zodiac killer sent four coded letters. Of the four ciphers, only one has actually been solved.

His letters were written in two parts. The first part was usually written in plain text, while the other was in cipher text, in which he claimed contained his identity. In the plain text part, he threatened newspapers to publish his letters or else he would kill more innocent people. In other segments of his letters, he listed the names of his next victims, creating havoc amongst the Bay area. His goal was to use the media to instill fear in Bay area citizens, and it worked. As cryptographers dug deeper into his letters, they were able to find out what drove the Zodiac killer to keep killing.

Of the four ciphers letters he sent, one was a three-part coded message, sent to three different press companies, making a 408-symbol cipher. His other famous cipher letter contains a 340-character cipher, which still doesn’t have a definitive solution. After the Zodiac killer sent his 408-symbol cipher (Z408), he sent another message to the police stating that if they could solve that cipher “they will have me.” To understand what the Zodiac killer meant by this, we will have to first see how the message was deciphered.

In 1969, two schoolteachers Donald and Bettye Harden managed to crack the Z408 cipher. The Z408 cipher consisted of random symbols corresponding to a plain text message. While Zodiac killer’s ciphers made him seem to be a genius, his Z408 cipher was not all that difficult to solve. It was a homophonic simple substitution cipher. In a basic simple substitution cipher, each ciphertext letter corresponds to a plaintext letter. However, in a homophonic substitution cipher, more than one ciphertext letter could correspond to a plaintext letter. This may seem tricky, but historically speaking, this cipher was far easier than any cryptanalyst would have expected (“Zodiac Killer Ciphers,” 2012).

To decipher the Z408 cipher, Donald and Betty Harden essentially looked for common patterns, and plugged in letters that might fit into the ciphertext. After analyzing the text, they noticed certain symbols appeared more frequently than others. For example, there were a high number of double symbols (double letters) found in the ciphertext. In frequency analysis, the letter “L” is doubled most frequently in English. Because the message came from a serial killer, they figured that the double letter “L” must be followed by the letter “I” creating the word “KILL”. In cryptography terms, the word “KILL” served as the “crib,” a word that could be plugged into other parts of the message to determine other phrases. While the message had a few misspellings, the meaning of the message was clear.

The cracked code offers frightening insight into the Zodiac killer’s mind. According to the plain text message, he was attempting to collect slaves for the afterlife. While the plain text message gave police the reason for his serial killing, the message never mentioned his name. According to the message, he refused to give up his identity because it would “slow down or stop [his] collection of slaves” (“Zodiac Killer Ciphers,” 2012).

While the Hardens managed to solve the Z408 cipher, the last 18 letters of the plaintext were “EBEORIETEMETHHPITI.” Seemingly jumbled text, cryptanalysts believe these letters are filler letters, used make the cipher three equally sized parts. Others believe that the letters can be rearranged to the name of the Zodiac killer (“Filler Theory,” 2009). These last 18 letters could be rearranged to make 741,015,475,200 transpositions, making the anagram almost impossible to decipher. Maybe the Zodiac killer was referring to the last 18 letters when he stated that the police would “have him.” Could the last 18 letters actually contain his name, or was it simply another method employed by the Zodiac killer to drive society insane? While the Z408 cipher has been solved, the mystery behind the last 18 letters still remains.

Adding to the fear that he once caused, the Zodiac killer still remains uncaught to this day. Recently however, Corey Starliper from Tewksbury, Massachusetts, claims to have cracked the Z340 cipher, by recognizing that Z340 is Caesar shift cipher (or a cipher where each plain text letter is shifted 3 letters down the alphabet). You may be wondering why the police didn’t decrypt a simple shift cipher earlier? Before Starliper actually applies the Caesar shift, he arbitrarily converts each Zodiac symbol to a Latin letter. The reason why the police were unable to solve the cipher was because the cipher consisted entirely of Zodiac symbols. This process seems to be a bit unreliable, considering Starliper’s method relies on his own assumptions. Surprisingly, the cipher message yields a message with English phrases, but not full English sentences (Muessig, 2011).

Interestingly enough, the last few phrases of the plaintext yield the words “MYNAMEISLEIGHALLEN.” Leigh Allen was a suspect while police were still investigating the case, however, his DNA did not match the DNA found in the envelopes of the Zodiac letters (Winkles, 2011). Many cryptanalysts question the accuracy of the decipherment but one thing is for sure: if a simple shift cipher of three was used, and it yielded a name as well as other phrases that would be used by a serial killer, it may just be an accurate decipherment. There is no proof that Leigh Allen is the Zodiac Killer. For all we know, the Zodiac killer could be framing Leigh Allen (Winkles, 2011).

Cryptography has made this case even more mysterious, and surprisingly, never actually helped investigators catch the Zodiac killer. However, cryptography has truly helped us discover more about one of the most elusive serial killers in history.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. The essays are shared here, in part, to give the students an authentic and specific audience for their writing. For more information on this cryptography seminar, see the course blog.

References

Muessig, Ben. (2011, July 7). Corey Starliper, Massachusetts Man, Claims He Cracked Zodiac Killer’s Code. The Huffington Post.

Sifakis, Carl. (2001). Zodiac Killer. The Encyclopedia of American Crime.

Winkles, Regina. (2011, February 4). Zodiac Killer: Identity Solved?

“Z 408 Cipher – Filler Theory.” (2009). Zodiologists.com.

“Zodiac Killer Biography.” (2012). Biography.com.

“Zodiac Killer’s 408 Character Cipher.” (2009). Zodiologists.com.

“Zodiac Killer Ciphers.” (2012, June 24). Throw the Book at Him.

February 22, 2013

Secrets Abroad: A History of the Japanese Purple Machine

by Alberto Perez (Vanderbilt University)

When one thinks about cryptography or encryption in World War II, the first thing that comes to mind is the Enigma Machine used by the Germans, whose code was broken by the Allies and used as a secret tactical advantage over the Nazis. What many people don’t know is that during World War II, the Japanese also developed a series of encryption devices that improved upon the Enigma Machine and were used to transport their top level military secrets.

Upon the trust of Hitler and other German officials, Japanese Baron Hiroshi Oshima bought a commercial Enigma Machine from the Germans in hopes of developing a new version for the Japanese (Japanese Purple Cipher). This effort resulted in the creation of a new “enigma machine,” code-named “Red” by the US. The Japanese Navy used it from about 1931 to 1936, when the device’s cryptographic method was broken by the US Signal Intelligence Service (Balciunas). Unfortunately for the US, the decryption of Red was not kept very secret and the Japanese became suspicious.

Soon after, the Japanese began creating a new system to encipher their messages. In 1937, the Japanese created the “97-shiki O-bun In-ji-ki” or “97 Alphabetical Typewriter,” named for its creation on the Japanese year 2597. This device was better known by its US code-name, “Purple” (Japanese Purple Cipher).

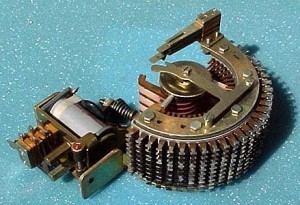

The Purple Machine was made up of two typewriters as well as an electrical rotor system with a 25 character alphabetic switchboard. Like the Enigma Machine, the first typewriter was the method in which the plaintext, or unencrypted message, could be manually inputted. The typewriter was built to be compatible with English, romaji, and roman, adding a level of mystery through language choice.

Unlike the Enigma Machine, which presented the text in the form of blinking lights, Purple used a second electric typewriter, which would type the cipher text, or encrypted message, onto a piece of paper (Balciunas). This was a huge advancement to the Enigma Machine, which would require two people to operate (one typing and one to record the projections) because it only required one person to operate and would reduce human errors. The only drawback to this was in the increased size and weight of the Purple Machine, which rendered it unsuitable for use in combat locations (Balciunas).

(Photo Credit: Edwards Air Force Base)

(Photo Credit: Edwards Air Force Base)

The Purple Machine enciphered the messages with the use of its four rotors and switchboard. Like the Enigma Machine, the machine would not only have an unknown method of encryption, but also a secret key that was changed on a daily basis. This meant that even if a Purple Machine was stolen, it would be useless without the key of the day. Additionally, as the key changed every day, code breakers would not be able to find patterns in messages sent over several days. The daily key would be inputted into the device by the arrangement of the switchboard and rotors. The switchboard contained 25 connections, which could be arranged 6 pairs of connections, yielding over 70,000,000,000,000 possible arrangements which would determine the method of encryption (Japanese Purple Cipher). Additionally, the rotors could be arranged in various starting positions that would also vary the encryption method. The rotors of the machine were “stepping-switches,” which would rearrange themselves as each letter was inputted and scrambled the alphabet used for the next letter. The Purple Machine would use hundreds of thousands of cipher alphabets before it would repeat one eliminating any obvious patterns in the cipher text (PURPLE). This made the Purple Machine – just like the Enigma Machine – so difficult to crack.

In order to decipher a message, the switchboard and rotors would need to be set with a key inverse to that of the key used to encipher. The cipher text would then be plugged into the first typewriter and the machine would type the plaintext (Taipu).

(Photo Credit: Duke University)

(Photo Credit: Duke University)

The Purple cipher was used to send secretive messages overseas mostly to diplomats and military officials in Washington, Berlin, and London where Japan did not want unintended recipients snooping around (Balciunas). Breaking the Purple Machine was a daunting task for many reasons other than the complexity of the code itself. While trying to break a code, the more cipher text the code breaker has, the easier his/her task. As the messages were being sent into the US and England, it would have been easy for the governments to seize the messages. Unfortunately, because the machine was new and still not mass produced, only the most secret military messages were being sent, and code breakers had a very limited amount of cipher text to work with. However, because the code senders were inexperienced with the new system, some messages were sent in both the Purple cipher as well as the broken Red cipher, making it possible for the texts to be compared. Additionally, as time passed, the Purple code was used more often and the US had a plethora of cipher text to work with (Japanese Purple Cipher).

In 1939, cryptography expert William Friedman was hired by the US Army to work on breaking the Purple cipher. Eighteen month into his work Friedman suffered a mental breakdown and was institutionalized (Japanese Purple Cipher). Fortunately, he was able to make some progress before this and using his incomplete work, other members of his team were able to make continued progress. A substantial chunk of the code was broken, and even though a Purple Machine had never been seen by American code breakers, eight functional replicas of the Machine were created. Eventually, Purple Machine’s method of encryption was completely discovered. This, however, did not mean that the messages could be broken because the daily keys being used were still a mystery to code breakers.

In time, Lt. Francis A. Raven discovered a pattern being used by the Japanese in their daily keys. He noticed that each month was broken into three ten day segments in which a pattern was discerned (Balciunas). With the final touches made to the puzzle by Lt. Raven, the Purple cipher was effectively broken and Japanese secrets were exposed.

The Purple Cipher was one of the most complex and well developed cryptographic methods of its time, and although it was eventually cracked, it kept top secret Japanese messages from prying eyes for almost two years during World War II. After a great effort by US cryptanalysis the code was broken and used against its makers, tracking Japanese Naval troop movement as well as other military communications. Unlike the Red Cipher, the US tried taking full advantage of this by keeping it a well-guarded secret from the Japanese and its allies so that the messages would continue to be sent in the broken code (Japanese Purple Cipher). The US ceased and broke a multitude of Japanese secret messages, even some containing the plans for the attack on Pearl Harbor which could have been used to prepare. However, as history reveals, not all of these were used to their full potential.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. The essays are shared here, in part, to give the students an authentic and specific audience for their writing. For more information on this cryptography seminar, see the course blog.

References

Balciunas, Marijus. (2004). Japan’s Purple Machine.

Japanese Purple Cipher. Cipher Machines.

Taipu, Angooki B. The PURPLE Machine. 97-shiki-obun In-ji-ki.

February 21, 2013

Rasterschlüssel 44: The Stencil on Steroids

by Justin Yeh (Vanderbilt University)

An Allied cryptanalyst intercepts the message, “JDNTOENVIPDJ,” during World War II and attempts to decrypt it. He assumes it was encrypted using the German Enigma machine and performs the standard cryptanalysis, resulting in the message “PQNXLATIDNW.” He is completely baffled…the Allies had already broken the Enigma, so why was this message indecipherable?

An Allied cryptanalyst intercepts the message, “JDNTOENVIPDJ,” during World War II and attempts to decrypt it. He assumes it was encrypted using the German Enigma machine and performs the standard cryptanalysis, resulting in the message “PQNXLATIDNW.” He is completely baffled…the Allies had already broken the Enigma, so why was this message indecipherable?

The Germans had invented a new cryptographic weapon.

The Germans’ new cipher, the Rasterschlüssel 44, was introduced in 1944. Ironically, the origins of this new German cipher can be traced to British cryptography (Rijmenants). The cipher was used in the field, mainly by police forces and the army (Cowan 2004) instead of by diplomatic officials. The Rasterschlüssel 44 (RS 44) was a hand cipher, meaning that it could be implemented with pencil and paper, unlike the German Enigma, which required a machine to encipher and decipher a message. Like all hand ciphers, the RS 44 needed to balance security strength and convenience. The cipher had to be complicated enough to withstand decryption efforts, but not so complicated as to be difficult to use.

Even though the RS 44 is a relatively unknown cipher, it still played a substantial role in WWII. The Allies had already broken the Germans’ previous field cipher, the Double Playfair cipher, and all of the messages enciphered with the Double Playfair were being read (CryptoDen). The RS 44 allowed the German military and field troops to communicate securely without fear of revealing critical military strategies to the Allies. Had the RS 44 failed to secure German communications, the Allies would have gained a tremendous tactical advantage. Cowan (2004) lists translated messages sent on February 3rd, 1945 that were enciphered with the RS 44:

“An additional 16 cubic metres Otto fuel have been allocated from Muerlenbach delivery #IS20 to enable 3rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment to be brought up more rapidly.”

“Combat elements of II Battalion have set-off on foot. I Battalion will leave tonight by truck.”

The Allies were too slow in decrypting these messages to be able to react to this information, but these messages provide examples of the subject matter and importance of the content enciphered using the RS 44.

Mechanics

The method by which the RS 44 encrypts a message can be seen in the cipher’s name; “Rasterschlüssel” means “grid key” in German. The basic principle of the RS 44 is that the plaintext (the message being enciphered) is horizontally written into a grid, and then the ciphertext (the scrambled message) is obtained by vertically reading the columns from top to bottom and writing out the letters. This method of scrambling letters is called columnar transposition.

Here is an example:

“plaintext message”

Resulting ciphertext: ptee les axs ita nmg

The grid scrambles up the letters so that the message can no longer be read. The RS 44 takes a basic grid and adds in a few tricks. First, the RS 44 uses a much larger 25×24 grid. The 25 columns are labeled with the numbers 1-25 in a random order. Each column is also randomly labeled with one of the 25 following pairs of letters:

aa ba ca da ea

ab bb cb db eb

ac bc cc dc ec

ad bd cd dd de

ae be ce de ee

Each of the 24 rows is also labeled with one of the 25 pairs (one pair is unused).

So a possible grid might look like this:

(Click on the image to see a larger version.)

The rows and columns are labeled as previously specified, but the grid is not complete. In each row, 15 of the cells are randomly blacked out, leaving only 10 white spaces in each row. Here is an example:

The grid pictured above resembles a crossword puzzle gone horribly wrong, but it is actually a finished stencil for the RS 44. Now that the grid is complete, the plaintext message can be inserted into the stencil. In our example, the plaintext message will be:

“Rainbow unicorn horns are immensely more valuable than those of even the largest narwhals.”

A hypothetical German cryptographer encrypting this important, nonsensical wartime message would begin by choosing any white cell in the grid. In this example, let’s say he chooses the cell in column “dc” and row “ee.” He would then write the message horizontally, putting one letter in each blank space and continuing to the next row when he reaches the end of one row. Once he finishes, the grid would look like this:

Now that the letters are inserted into the rows, the cryptographer obtains the ciphertext by reading down the columns, similar to the example with the “plaintext message” in the first figure above. However, instead of starting with the leftmost column and reading to the rightmost column, the RS 44 uses the numbered columns to determine the order in which the columns are read.

The cryptographer will choose a column based on the time the message is written and the length of the message: in this example, the column is “ec,” also numbered “8”. This column only contains the letters: “h,” “n,” and “a,” so those are the first three letters of the ciphertext. The next column is “bd,” which is labeled “9.” The remaining ciphertext is obtained by reading the columns from top to bottom in increasing numerical order. After all the columns are read, the ciphertext message reads:

“HNANOESONMEGNANAALHRNTRAUHVSCWSTNAOAWVIBHMEFLREMLRNRLTIOEAEEBRSUIYEHREOTOLSEN”

However, our cryptographer is not finished. In order to indicate the cell in which he started writing his plaintext, he uses a 5×5 matrix of letters. The coordinates of the starting cell can be written as “dcee,” and he substitutes letters from the matrix, resulting in the letters “rvhp.” This substitution must be attached to the beginning of the message before it can be sent. In addition, the time that the message was written (16:21) and the message length (76) must also be included. This extra information is written as 1621-76-rvhp.

Finally, the message is ready to be sent:

1621-76-rvhp HNANOESONMEGNANAALHRNTRAUHVSCWSTNAOAWVIBHMEFLREMLRN RLTIOEAEEBRSUIYEHREOTOLSEN

Breaking the RS 44

The strength of the RS 44 lies in the randomness of the stencil. Accounting for repeat configurations and configurations that would not scramble the message, the number of stencil possibilities is still 2.06×10185 (Rijmenants). An Allied cryptanalyst that knew the dimensions of the stencil faced the impossibility of actually guessing the configuration of the stencil.

Despite the astronomical number of stencil possibilities, the RS 44 is not infallible. The number of possible stencils only protects the cipher from random guessing. However, the Allied cryptanalysts used other methods to break the cipher. They used captured stencils to decipher messages, but they had actually cracked the RS 44 without using a stencil. The enciphering technique of the RS 44 was secure; however, the Allies exploited the cipher’s improper implementation. Cryptographers using the stencil were prone to many mistakes, which required some messages to be sent more than once. The Allies used these similar messages to determine the plaintext and derive the stencil. Despite being broken, the RS 44 was still a relative success. The strength of the RS 44 was not that it was unbreakable, but that it was unbreakable in a short time frame. By the time the Allies had decrypted a message enciphered with the RS 44, the message was no longer relevant. Unlike Enigma, which was meant to be unbreakable, the RS 44 only had to be unbreakable for a given period of time. The fastest decryption of the RS 44 by the Allied cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park was ten days, but most messages took longer (Cowan 2004).

Weaknesses of the RS 44

As mentioned earlier, the cryptographers who enciphered messages with the RS 44 made many mistakes. This was due to the difficulty of using the stencil. Cryptographers placed tracing paper on the stencil and wrote on the tracing paper. Errors in counting occurred and the cipher was almost impossible to use in wet conditions (Cowan 2004). The mistakes in enciphering resulted in the decipherment of gibberish, which required a second message to fix the mistake. The resending of faulty messages greatly aided the Allies and their decryption efforts. The rules for enciphering a message were given in a 20-page instruction manual, but some cryptographers were still confused about the process (CryptoDen).

Another weakness of the RS 44 was the manufacture of the stencils. The pattern of the blacked out cells in each row was constructed using a rod. The Germans initially only had 36 rods to choose from, which meant that the millions of possible arrangements of black cells in each row was reduced to 36. If the Germans used a greater variety of rods, and therefore a greater variety of stencils, then the RS 44 would have been more secure. A wartime shortage of materials prevented the mass manufacture of different rods and stencils. In addition, the stencil used for enciphering messages had to be replaced daily. To produce a month’s supply of stencils, a book of 31 stencils had to be assembled and distributed to every unit that communicated using the RS 44. The strain on German supplies was significant; the RS 44, with its stencils and tracing paper, required 30 tons of paper per month (Cowan 2004).

Final Thoughts

Overall, the RS 44 succeeded in securing German messages. The Allied forces did manage to break the cipher and discover the mechanics, but not in a reasonable time frame. The RS 44 stencil provided a sufficient variability and number of possibilities to maintain the security of the message. However, difficulties in its application ultimately led to its decryption, and limited supplies inhibited its effectiveness. The true value of the RS 44 lies in the fact that scrambling a message using a grid with a few added layers of complexity can stump cryptanalysts but does not even require advanced technology, just paper and a pencil.

This post is part of a series of essays on the history of cryptography produced by students at Vanderbilt University. The students wrote these essays for an assignment in a first-year writing seminar taught by mathematics instructor Derek Bruff. The essays are shared here, in part, to give the students an authentic and specific audience for their writing. For more information on this cryptography seminar, see the course blog.

Works Cited

Cowen, M. J. (2004). Rasterschlüssel 44 – the epitome of hand field ciphers. Cryptologia, 22(4), 115-148.

CryptoDen. (n.d.). Rasterschluessel 44 (RS 44): Introduction. Retrieved from http://www.cryptoden.com/index.php/21...

Rijmenants, D. (n.d.). Rasterschlüssel 44. Retrieved from http://users.telenet.be/d.rijmenants/...

Image: “Goal setting,” Justin See, Flickr (CC)

February 20, 2013

Getting My Books Into Readers’ Hands

by Tracy Barrett (W&M Contributor)

Historical fiction has devoted—sometimes rabid—fans. In the case of historical fiction for young readers, that fan base is still devoted, but it tends to be pretty small. Most kids are interested in reading about their contemporaries—whether human or zombie, or whatever the beast du jour is—rather than about the past, and often they come to our work through a teacher or librarian. So if we want our books to be read, we have to please two very disparate audiences: not only our readers, but also the adults in their lives, mostly in school settings.

Now there’s a new way to help us connect with teachers and librarians.

You’re probably familiar with the educational reform called No Child Left Behind (don’t get me started). There’s a new program that’s received a lot less fanfare: the Common Core State Standards Initiative, sometimes called the Core Curriculum. Its aim is to establish a shared base of knowledge and skills among K-12 students, and there’s a lot in it that writers of nonfiction and historical fiction can draw on to make their books more appealing in schools. And the more appealing and curriculum-appropriate a book is, the more likely it is that a teacher or librarian will suggest or even require it of her students.

There’s a set of standards for math, but what interests me as a writer are the English Language Arts standards, summarized here as follows: “The Standards set requirements not only for English language arts (ELA) but also for literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Just as students must learn to read, write, speak, listen, and use language effectively in a variety of content areas, so too must the Standards specify the literacy skills and understandings required for college and career readiness in multiple disciplines.”

I find this exciting for me as a writer primarily of historical fiction, and also for my friends who write about the sciences. Students will be expected to write clearly about science and technology as well as the humanities. What better way for them to learn than by reading well-written books in those subjects?

And think of the opportunities for school presentations. I can talk about research, how I organize my findings, the use of primary and secondary sources—skills that students are to acquire in grades 6-12, my target audience.

I recently asked a group of librarians what I could do to make an author visit a success. Among their many suggestions was the reminder that every bit of programming they do must be curriculum based. The more clearly I can show them specific points where my presentation will enhance the core standards, the more likely the principal is to approve (and fund) my visit, and the more likely my books are to be read by the people I write for.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.