Holly Tucker's Blog, page 65

August 8, 2013

The “Gnome” of the Wrestling Ring

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Maurice Tillet was a bear of a man: He stood 67 inches, weighed 270 pounds, and had the strength to tug a subway car along its tracks. He seemed a perfect competitor for professional wrestling during the late 1930s and 1940s, except for one startling disability. During his young adulthood, Tillet had developed an endocrine disorder called acromegaly, the result of his pituitary gland’s overproduction of growth hormone.

Maurice Tillet

Untreated, acromegaly can produce humans of gigantic size, such as Charles Byrne, known during the eighteenth century as The Irish Giant; Ted Cassidy, who played Lurch in The Addams Family; and Richard Kiel, the evildoer in James Bond films who topped seven feeet. In Tillet, however, acromegaly did something different. While leaving him of normal stature, it grew his head to gigantic proportions and gave his body a barrel-like appearance not unlike Fred Flintstone’s. Instead of handicapping him in wrestling, the disorder proved to be a boon by lending him a dramatic appearance. Tillet thrived in the sport, spending several years as the reigning World Wrestling Federation champion.

Born to French parents in the Ural Mountains in 1903, Tillet developed normally as a child and drew attention for his slim build and sharp mind. His friends, who nicknamed him Angel, were impressed by Tillet’s ability to speak several languages. His family fled to France during the Russian Revolution, and soon after he began to notice a painful swelling over his body, the first symptoms of acromegaly. He gave up his dream of becoming a lawyer and joined the French navy.

While in the military, Tillet met a wrestling promoter who convinced him to take up the sport. Retaining his childhood nickname, he wrestled with great success in Europe and moved to North America after the outbreak of World War II. There he pinned one opponent after another, racking up his string of world championships. Wrestling fans were even more entranced by his appearance than his masterful technique. People, convinced he was a real-life ogre, saw him as a freak and a monstrosity.

In 1940, under the watchful cameras of LIFE magazine, Tillet underwent an examination by the then-noted (and now notorious) Harvard anthropologist Carleton Coon. The anthropologist took special note of Tillet’s oversized jaw and gigantic hands and feet. After measuring the wrestler’s head and other body parts, Coon suggested that Tillet “might be a throwback” to Neanderthal man, the magazine’s reporter noted. But Tillet was not a caveman — only an athlete who had made the most of a disability that now can be controlled by combinations of drugs, surgery, and other treatments.

Tillet continued wrestling into the 1950s — inspiring a host of “Angel” imitators who styled themselves a primitive brutes — when his prowess declined and his efforts no longer ranked as championship quality. Heart disease ended his life in 1954, but not before he consented to allow an artist to make a plaster death mask. A copy of that mask has a place of honor in the USA Weightlifting Hall of Fame. Tillet won election to the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in 2012.

RECOMMENDED READING

“The Angel.” LIFE magazine, March 4, 1940.

Beekman, Scott. Ringside: A History of Professional Wrestling in America. Greenwood Publishing,

Hornbaker, Tim. Legends of Pro Wrestling: 150 Years of Headlocks, Body Slams, and Piledrivers. Skyhorse Publishing,

August 6, 2013

Removing Bad Tattoos in Antiquity

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Today’s unwanted gang tattoos, names of ex-lovers,  outgrown cartoons, misspelled mottoes, and other mistakes on skin are printed over with complex designs or erased by long sessions with a laser. Painful — but not as painful or risky as the procedures invented by ancient Roman doctors for removing demeaning tattoos.

outgrown cartoons, misspelled mottoes, and other mistakes on skin are printed over with complex designs or erased by long sessions with a laser. Painful — but not as painful or risky as the procedures invented by ancient Roman doctors for removing demeaning tattoos.

Your visit would go like this: Clean the tattoo with natron and terebinth (turpentine). Bandage for five days. Day six: Return to the doctor, who pricks out the tattoo design with a sharp pin. He sponges up the blood and covers the mess with a layer of stinging salt. Now you run a strenuous mile or two to work up a lather and return to the doctor, who applies a caustic poultice of lye or powdered quicklime. Your tattoo will disappear in about 20 days. In its place, you’ll sport an ulcerated chemical burn that obliterates the old tattoo.

“I will tattoo you with images of hideous punishments suffered by the most horrid criminals in Hades!” This violent verse threatens revenge by tattoo, probably written by the poetess Moiro of Byzantium in about 300 BC. Around the same time, a woman named Bitinna summons a professional tattooer of criminals and slaves to bring his needles and ink to punish her unfaithful lover, in a Greek play by Herodas called “The Jealous Woman.” Tattoos today are decorative and voluntary, even if sometimes recklessly selected and deeply regretted later. But in ancient Greek and Rome tattoos were punitive, forcibly inflicted on slaves, prisoners of war, and wrong-doers. Tattooing captives was common in wartime. For example, in the fifth century BC Athens defeated the island of Samos and tattooed their Samian prisoners’ foreheads with Athens’ mascot the owl. Later, the Samians crushed the Athenians and tattooed their captives with the Samos emblem, a warship. In 413 BC, after Athens’ disastrous defeat at Syacuse, 7,000 Athenian soldiers were captured. Their foreheads were tattooed with the symbol of Syracuse, a horse, and they were sent as slave to work the quarries. Slaves were routinely tattooed and runaway slaves had sentences such as “Stop me, I’m a runaway” crudely gouged and inked into their faces.

These dehumanizing tattoos were not artistic or carefully applied: ink was simply poured into grooves carved in flesh with three iron needles bound together, with no thought of hygiene. There was copious bleeding; infection could be ugly. The indelible marks turned one’s body into a text recording forever one’s captivity, enslavement, or guilt. Naturally, there was a market for hiding or removing shameful tattoos, should one be lucky enough to escape a master or prison. Some opted for a painless approach: Grow long bangs to cover forehead tattoos. During the Roman era, pirates’ crews offered a haven for many criminals and runaway slaves. The dashing pirate scarf trick—tying a bandana around their foreheads—was invented to mask the tattoos of one’s old life.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

July 19, 2013

The Curious Case of the Mummy in the Cupboard

By Jo Marchant

It has not been a peaceful afterlife. Since its discovery 90 years ago, Tutankhamun’s mummy has repeatedly been disturbed in the name of research – from its dramatic unwrapping in the 1920s to controversial CT scans and DNA tests of the present day.

In my book The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy, I wanted to tease apart the results of these studies, getting to the bottom of scientists’ arguments to see what their work tells us about the life and death of this ancient king. But along the way I became fascinated by the lives of the scientists themselves, and the unexpected paths that drew them to Tutankhamun.

Douglas Derry, the Scottish anatomist who unwrapped the king’s body in 1925, began his career in the harsh desert of Nubia, measuring tens of thousands of skeletons and natural mummies buried in the sand. It was a desperate race against time to uncover the secrets of the region’s ancient inhabitants before the rising floodwaters of the Aswan Dam obliterated their civilization forever.

He and his colleagues spent oven-hot seasons there between 1907 and 1911, eating rice and canned sardines amid swarms of flies and noting their results on cards that were tinted blue to protect their eyes from the glare of the sun. One gruesome find, a trench filled with young men with broken necks, plunged the team into a debate over humane methods of hanging (a hot topic back in Britain) including a series of clandestine experiments to drop cadavers down the lift shaft of St Thomas’s Hospital in London.

Then there’s Scott Woodward, a Mormon geneticist from Utah and a pioneer of the study of ancient DNA. He shot to fame in the 1990s after reporting DNA from an 80 million-year-old dinosaur (which later turned out to be human contamination), then began testing several royal mummies kept in the Egyptian museum in Cairo, in an attempt to work out their confusing family relationships.

The project was mysteriously cancelled before he could sample Tutankhamun. Several Egyptologists have claimed it was because the authorities feared he might use his results to prove that Egypt’s rulers were in fact Jewish. A central belief of the Mormon faith is that if you can identify your dead ancestors you can convert them – might Woodward even have aimed to convert the pharaohs? A subsequent attempt to test Tutankhamun’s DNA in 2000 was also cancelled at the last minute, for reasons of “national security.”

But my favourite story comes from the drab Welsh seaside resort of Rhyl. In April 1960, a grandmother and landlady named Sarah Jane Harvey was admitted to hospital with a stomach tumor. While she was there, her son-in-law decided to decorate her home as a surprise for her return.

There was a locked cupboard on the landing that she had told him never to open, but to do a proper job of the painting, he forced the door with a knife. Inside, covered with dust and wearing a blue nightgown, was a hideous mummy.

Harvey was arrested for murder and the British press went wild, running stories of secret lab tests revealing gruesome embalming rituals, and speculating about whether the dead woman had been pickled in a bath of saltwater, or plunged into a vat of pitch. Local pathologists, stumped by her condition, called in an anatomy professor named Ronald Harrison.

The mummification was a freak accident, Harrison concluded. A draught of warm air had dried the body before it could decompose. He identified the victim by testing the mummy’s blood group and matching it to relatives of Frances Knight, a previous lodger of Harvey’s, who hadn’t been seen for twenty years.

It was cutting-edge science for the time, and it got Harrison thinking about how molecular techniques might reveal family relationships of much older bodies. He went on to study the royal mummies of ancient Egypt, including King Tutankhamun, X-raying them but also bringing home scraps of tissue to determine their blood groups and compile a tentative family tree.

In recent years, Egyptian scientists have continued efforts to uncover the mysteries of these enigmatic rulers, by CT scanning them and analyzing their DNA. Their multimillion-dollar project has featured in glossy TV documentaries and triggered headlines around the world. But it all started with a flood, a dinosaur, and a little old lady from Rhyl.

Image: Anatomist Ronald Harrison (back, left) and members of Egypt’s antiquities service with Tutankhamun’s mummy in December 1968

Jo Marchant is the author of The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy, was published by Da Capo press in June 2013.

July 18, 2013

The Emperor Changes His Mind

by Pamela Toler

Emperors tend to be known for their military conquests: Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, Napoleon. The emperor Ashoka, who ruled the Maurya empire of India from 269 to 232BCE, is best known for his conversion to Buddhism and subsequent rejection of military aggression .

In the early years of his reign, Ashoka was a successful warrior who expanded the borders of his empire to include most of modern Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan–an area larger than any other Indian ruler would command.

In 261, Ashoka led a brutal expedition against the neighboring kingdom of Kalinga (modern Orissa). Sickened by the loss of life, he converted to Buddhism and proclaimed his conversion to his subjects in a series of inscriptions engraved on rocks and pillars throughout his kingdom, the 3rd century BCE equivalent of billboards. In what are now known as the “Ashokan edicts”*, which appear to have been written by the emperor himself, he outlined his new dedication to “moral conquest” in place of military campaigns and rules for running a Buddhist kingdom.

In pursuit of his Buddhist ideals, Ashoka banned the animal sacrifices that were an important part of the Vedic religion, reduced the consumption of meat in the palace, and replaced the royal pastime of hunting with pilgrimages to Buddhist holy places. Despite his support of the Buddhist principle of ahimsa (non-violence) at a personal level, Ashoka never wholly embraced pacifism; he guaranteed the peace of his enormous empire with an army that included 600,000 foot soldiers, thirty thousand cavalry and nine thousand war elephants.

When modern India gained its independence in 1947, the new state chose the cluster of four lions that serve as the capital on the Ashokan pillar at Sarnath as its emblem. The choice was intended as a statement of India’s commitment to religious tolerance within a secular state.

*You can read a translation of the edicts here.

Image credit: mkistryn / 123RF Stock Photo

July 14, 2013

Caecilius’ Willy

by Caroline Lawrence (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

by Caroline Lawrence (Wonders and Marvels contributor)Students and teachers familiar with the Cambridge Latin Course were in for a shock at the British Museum Pompeii exhibition this summer. We saw Lucius Caecilius Iucundus as never before and many of us exclaimed Herclé! (By Hercules!)

Everybody knows his face from the famous orange textbook 1. His first appearance in the garden is now a meme – Caecilius est in horto – and he has even met Dr. Who. Using delightful line drawings and deceptively simple stories, the clever authors lull us into a false sense of security until the story ends in tears with < Spoiler Alert!> Caecilius’ moving death during the eruption of Vesuvius. The faithful slave Clemens finds his dying master under a partly collapsed wall. Clemens wants to stay, but Caecilius tells him to make sure his son and wife survive. “Clemens, abi!” he gasps. (“Clemens, go!”) Then he dies with the faithful watchdog Cerberus refusing to leave his master’s body. *Sob!*

The Cambridge Classics School Project textbook informs us that a bronze portrait bust of Caecilius was found in his house in Pompeii, along with a dog mosaic: one of about half a dozen examples that have survived from the ancient world. There were also lots of wax tablets showing us that he was an argentarius, a cross between a banker and auctioneer. Today we would call him an entrepreneur.

The Cambridge Classics School Project textbook informs us that a bronze portrait bust of Caecilius was found in his house in Pompeii, along with a dog mosaic: one of about half a dozen examples that have survived from the ancient world. There were also lots of wax tablets showing us that he was an argentarius, a cross between a banker and auctioneer. Today we would call him an entrepreneur.

What the book doesn’t tell us is that wax tablets and other records bearing his seal cease a few days before the big earthquake of AD 62, leading many scholars to believe that Caecilius died in that earthquake, 17 years before the infamous eruption. There is also a famous relief of the earthquake in the lararium of the townhouse that he (presumably) left to his children.

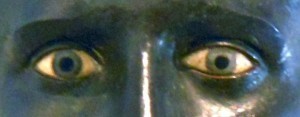

Caecilius’s ugly-yet-loveable mug appears throughout the book and when you enter the atrium of the British Museum’s exhibit you first get a thrill of recognition, and then a shock when you see how the artist really has depicted him warts and all. But a bigger shock awaits as you lower your gaze and see that Caecilius’s head is part of a herm, a rectangular plinth with a head on top and male genitalia half way down the front. Sure enough, there is Caecilius’ willy! Edepol! (Pollux!) They never let on about that in the Cambridge Latin Course!

So what on earth is going on? Is someone playing a nasty practical joke on our beloved banker?

So what on earth is going on? Is someone playing a nasty practical joke on our beloved banker?

As ever, the answer lies in the fact that the Romans are like us, and yet not like us. I keep blogging about how superstitious the Romans were and Evil Eyes and such things, and this herm of Caecilius is a perfect example.

Nobody is exactly sure what a herm is or how they originated. The best theory is that they started as piles of rocks at crossroads or boundaries, always dodgy places in ancient Rome. Later this pile-o-rocks was superseded by a wooden or stone plinth topped with the head of a god and with the genitals about midway down. The penis (usually erect but sometimes flaccid) was a very common apotropaic device, to turn away evil. It represents the animal nature or power of a man. It also has an “eye”. As the poet Martial says of the male member: sit lusca licet, te tamen illa videt. (“Although it has only one eye, it’s looking at you!” Martial IX.37).

But a herm is doubly apotropaic because a staring face is another very powerful means of frightening away evil and/or evil doers. You can see the place where glass paste or a gemstone would have given Caecilius realistically staring eyes. Remember the recent story about how bike thefts in Newcastle went right down when this sign was put up?

In effect, herms were like ancient scarecrows that kept away trespassers, thieves and bad luck.

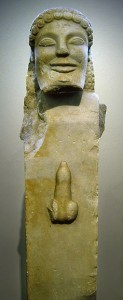

The oldest recognisable herms are from the Archaic period. The head on top is usually that of Hermes, Dionysus or Hercules, all deities of fertility or power. (The name Hermes probably comes from the Greek word herma which means “a stone set up”.) Herms changed appearance as sculpture evolved. You may remember the story of how a volatile young statesman named Alcibiades (allegedly) defaced the herms of Classical Athens.

Later, in Hellenistic times, Greeks started to put the heads of ephebes (high born youths) on the herms. Again we’re not sure exactly why, only that these herms adorned and protected the gymnasium where these young men worked out.

By Cicero’s time (1st century BC) intellectual Romans thought it would be fun to put realistic portraits on herms. We have a roomful of examples from the opulent House of the Papyri near Herculaneum (template for the marvellous Getty Villa in Malibu). This house was famously owned by a man who followed the Epicurean philosophy.

By Cicero’s time (1st century BC) intellectual Romans thought it would be fun to put realistic portraits on herms. We have a roomful of examples from the opulent House of the Papyri near Herculaneum (template for the marvellous Getty Villa in Malibu). This house was famously owned by a man who followed the Epicurean philosophy.

The Greek ideal of beauty was a small penis, whereas the Romans thought the bigger the better when it came to turning away evil. The fact that Caecilius’ member is small and limp hints at possible connections with Greece. Perhaps, like many higher-born Romans, he studied rhetoric in Athens. The modest, stylised, almost apologetic willy does not really match the portrait bust above it, which as I have said is literally warts and all. (In a recent lecture at the British Museum, curator Paul Roberts commented that the face is as close as possible to the man’s to give the spirit of him.)

The herm was not set up by Caecilius himself, but by one of his freedmen, and possibly after his death. It is dedicated to the “genius” or spirit of Caecilius: GENIO L[UCII] NOSTRI FELIX L[IBERTUS] “To the Genius of our Lucius. I, Felix, his freedman [commissioned it]” It was probably a kind of ancestor statue, designed to be worshipped along with the other household gods. But it also served another function. With face and phallus facing the front door, the herm averted evil and protected not only the contents and inhabitants of the house, but perhaps also his entire legacy.

The herm was not set up by Caecilius himself, but by one of his freedmen, and possibly after his death. It is dedicated to the “genius” or spirit of Caecilius: GENIO L[UCII] NOSTRI FELIX L[IBERTUS] “To the Genius of our Lucius. I, Felix, his freedman [commissioned it]” It was probably a kind of ancestor statue, designed to be worshipped along with the other household gods. But it also served another function. With face and phallus facing the front door, the herm averted evil and protected not only the contents and inhabitants of the house, but perhaps also his entire legacy.

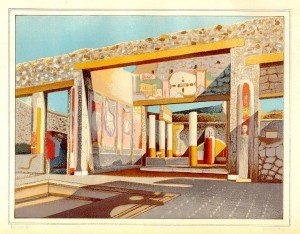

Just as we find the contrast of his realistic face and coy genitals incongruous, so the Romans might have had a chuckle upon first seeing it. But laughter is another apotropaic device. So this herm is triply apotropaic while still hinting at the founder’s wit and erudition. (below: antique print shows the possible original location of Caecilius’ herm at the back of the atrium and just before the tablinum, facing the front door.)

This herm of Caecilius serves to remind us how pervasive was the daily threat of random calamity and how charmingly the Romans addressed it. Ironically, it also underlines how ineffectual all their charms, offerings and prayers were against the power of Vesuvius.

For a clearly-written article on the apotropaic nature of the penis, read Claudia Moser’s delightful undergraduate thesis, Naked Power. It will tell you everything you wanted to know about the apotropaic phallus but were afraid to ask.

To introduce children to the concept, buy them The Colossus of Rhodes, which has winged willies on the very first page. But all in the best possible taste.

July 8, 2013

Decades later, a mysterious archival theft still hurts

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Like many of my colleagues at Wonders & Marvels, I depend upon publicly accessible archival collections when I research my books and articles. For my forthcoming book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist: Hermann Göring, Douglas M. Kelley, and a Fatal Meeting of Minds at the End of WWII, for example, I used public archives in New York, Maryland, and California to supplement the research I conducted in a private family archive. Those public records added crucial context and detail.

[image error]

Still missing: The “Stella” daguerreotype portrait of Edgar Allan Poe

I mention this to explain why I regard the theft of materials from archival collections as a heinous crime. When crooks steal valuable goods from archives, they remove information and ideas from circulation and damage the trust that archivists place in the visitors who arrive to examine historical materials.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of an infamous archival heist that has never been solved. In August 1973, workers at the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library began noticing items missing from their celebrated collection of American literary manuscripts and artifacts. The archive held manuscripts of unpublished novels by William Faulkner, Louisa May Alcott’s bookkeeping ledgers, and letters written by U.S. presidents, among other treasures. Over several months, somebody — or perhaps more than one person — used a key kept in a locked cabinet to gain access to the library’s archival strong room: a chamber located behind several bolted doors, which a newspaper reporter called “the vault room far down among the deepest of the library structure’s recesses.”

As the Virginia archivists inventoried the loss, they found missing such precious items as letters by Thomas Jefferson, Francis Scott Key, and George Washington; papers formerly belonging to Alexandre Dumas, Charles Dickens, Aaron Burr, Samuel Clemens, and Robert E. Lee; a first-edition printing of Edgar Allan Poe’s first work, a poetry collection that included “Tamerlane”; and another first edition of Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. Perhaps the most sensational loss was the disappearance of an irreplaceable daguerreotype portrait of Poe, nicknamed the “Stella,” that had been with the University of Virginia (Poe’s alma mater) since 1921. Forty-five artifacts vanished with an estimated value of $100,000 (at least $525,000 in today’s dollars).

Authorities took the unusual step of publicizing the embarrassing theft in the hope that some artifacts might turn up in the open market. None of the missing items ever did, sparking fears that the thieves may have destroyed their loot.

Decades later, the loss of these artifacts from public use still resonates as a terrible blow to scholarship, readership, and American history. Let’s hope that someday they will return home. Until then, we can only guess at the hidden stories they could have told.

Recommended reading

Associated Press. “Rare Papers Are Missing From U.Va.” The Free-Lance Star (Fredericksburg, Va.), December 21, 1973.

Deas, Michael J. The Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe. University of Virginia, 1989.

Kelly, Brian. “Valuable Manuscripts Taken From University Library Vault.” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, April 28, 1974.

July 6, 2013

Rabies: Ancient Biological Weapon?

by Adrienne Mayor  (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

(Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Rabies spread by bites of infected dogs has been deeply feared since antiquity. The main vector is domestic dogs, but wild animals such as foxes and bats can transmit the disease to humans. Rabies is almost invariably fatal. The earliest record of canine rabies appears in Mesopotamian cuneiform law tablets from about 2000 BC. The codex set a heavy fine for an dog owner who allowed a dog with symptoms of the disease to bite another person. The disease’s zoonotic ability to jump from animals to humans is thought to have originated in Mesopotamia, reaching China in the sixth century BC. Rabies was known in ancient Anatolia by the fifth century BC, mentioned by Xenophon and Aristotle. As rabies spread to Italy and Europe, many Byzantine doctors and medieval medical writers described the symptoms and course of the dread disease (animal symptoms include snapping and biting, excessive drooling, hydrophobia).

Rabies arrived in Greece in the fifth century BC. The ancient temple of Athena at Rhocca (Crete) was notorious for rabid dogs. Athena of Rhocca was invoked to cure human victims of rabies. In about AD 200, the natural historian Aelian described an experiment to cure some young boys who had been bitten by rabid dogs near Rhocca, whose ruins are found south of Methymna, Crete. A doctor administered the toxic stomach acid of seahorses to his patients in an attempt to counteract the mad dog “venom.” This early attempt to fight poison/venom with another poison/venom (anticipating the principles of vaccines, chemotherapy, and venomics) failed and the stricken boys died.

Aelian remarked that a piece of cloth bitten by a rabid dog could imbue the fabric with deadly saliva, causing second-hand infection of anyone who came into intimate contact with it. The virus can indeed infect via an open wound. Aelian’s ominous comment insinuates that mad-dog “venom” could have weapon potential.

Sure enough, historical detective work uncovers two intriguing formulas for creating biological weapons in an ancient Indian manual of warfare. The Arthashastra by Kautilya (fourth century BC) tells how to make many different types of poison arrows. One recipe calls for mixing various toxins with the blood of a musk rat. “Anyone pierced with this arrow,” wrote Kautylia, “will be compelled to bite ten companions, who will each in turn bite ten more people.” The implication is that musk rats were a vector of rabies in India. The other poison arrow recipe calls for “the blood of a man and a goat to induce biting madness,” which sounds suspiciously like rabies. Perhaps goats were susceptible to rabid animal bites. Two thousand years later, in about 1500, the idea of “weaponizing” rabies occurred to Leonardo da Vinci, who envisioned a terror-bomb created from sulphur, arsenic, tarantula venom, toxic toads, and the saliva of mad dogs. In 1650, the Polish general Casimir Siemenowicz entertained a similar notion. He suggested placing “the slobber from rabid dogs” in hollow glass or clay balls and catapulting them on the enemy to cause “epidemics” of rabies. The effectiveness of such weapons is dubious, but the diabolical intentions are chilling.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

June 30, 2013

When three hundred historical novelists met together in one room….

Gorgeous authors Kris Waldherr and Stephanie Lehmann at the costume pageant

Well, it seemed nearly five hundred and it happened at the grand banquet of the semi-annual Historical Novel Society Conference in St. Petersburg, Florida. Writers who are fairly famous and those in the middle and those unknown to this point met together for two glorious days at the historical Renaissance Vinoy hotel whose veranda overlooks the bucolic Tampa Bay with its expensive boats and amazing old trees with Spanish moss.

The hotel comes with its live-in ghost, but the writers brought their own ghosts and packed thousands of years in their pockets. Biblical scholars discovered each other at the banquet, authors of royal fiction embraced. A great deal of talk was overheard about Victorian England and the life of Tudor spies. Someone walked around with a t-shirt which said, “Just finish the damn novel” – words I should heed. There were so many published authors at the book signing that I had a hard time finding a place to sit. Novelists stormed the bookshop and bought each others’ novels.

Anne Easter Smith’s novel of Jane Shore

If the Babylonian exile or Marie Antoinette’s court is where your soul lives, St. Petersburg Florida was a good place to be the third weekend in June.

According to their website, the HNS was founded in the UK in 1997.” At first it was conceived of as something of a campaigning society, because historical fiction was in the doldrums then. Or at least that was the perception. In time we began to realise that the sheer scale of the review magazine was the best argument you could make for the strength of the genre. We also realised that our reviews could grow to be the best and most complete guide to the genre. Over the last 15 years we have become very much an international society. We aim to review all US and UK mainstream published titles, and as many other English language books as we can. Ideally we would also love to cover foreign language titles.”

This was the fifth North American convention and writers came from all over the states, England, Ireland, South America and beyond. Panels on all subjects from truth in historical fiction to building an online presence were held. Authors looking for agents or editors pitched their novels and practiced their pitches with each other over wine in hotel rooms. Many cheerful overworked volunteers held it altogether. There were guest speakers including the inspirational Anne Perry who told us that a familiar loved book can hold your hand in dark times and get you through and C.W. Gortner (Christopher) who found his first publisher at the very first convention in Salt Lake City and who told a story of dedication and endurance for fourteen years before his wonderful career began.

speaker and novelist C.W. Gortner

The glorious lobby was full of soft chairs and sofas with new and old friends in small groups intensely conferring; the bars and tables of the three restaurants overflowed with writers talking about three millenniums of stories. And at 7:00 in the morning outside on a terrace to the sound of birds chirping, writer and yoga teacher Stephanie Renee Dos Santos gave a free class to early-rising writers.

The Saturday gala included a costume pageant with Margaret George wearing a dress from the movie Titanic and Teralyn Pilgrim as a very pregnant Vestal Virgin, inspired by her upcoming novel.

We all left each other with many hugs, many e-mail address interchanged. My dear three hundred colleagues: ten weekends would not be enough with all of you.

It is very little money to join the Historical Novel Society and worth every penny. http://historicalnovelsociety.org/ Perhaps I’ll meet you at the London convention in Fall 2014.

Teralyn Pilgrim as a too fertile Vestal Virgin

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

Buffon and the Beagle

By

Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

Beagles, that adorable and humble breed of hunting dog, were at the centre of a debate about the meaning of civilisation and nature in the eighteenth century. Long before Charles Darwin, scientists (or natural philosophers as they were called at the time) wanted to understand the process of breeding, as well as the differences between people of different cultures.

Dogs, with their wide variety of breeds and accessibility, provided a particularly fruitful ground of investigation. The work of French natural philosopher Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon was particularly controversial and well-known—so much so, that it made its way into the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2nd vol. (Edinburgh, 1771) under the entry for ‘canis’.

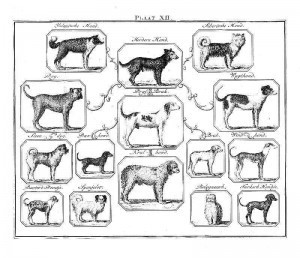

Dog Species Chart, from Buffon’s Natural History. Image Credit: http://vintageprintable.com/wordpress.

The Encyclopaedia summarised Buffon’s arguments for a wider audience. In his thirty-six volume Natural History (1749-1789), Buffon had suggested that all quadrupeds were descended from a small number of distinct types. Differences in climate, treatment or diet could result in variations, which Buffon saw in terms of improvement or degeneration. Buffon hypothesised that the first dog (the Adam of the canine world) would have been something like a shepherd’s dog, but “when brought up in a country fully civilised, as Britain or France, loses his savage air”. The dog also changed appearance. Rather than having thick and long hair or pointed ears, the dog became a bull-dog, mastiff or hound. These changes were not universal, however. For example, the bull-dog’s ears remained partly straight “and resemble in their manners and sanguine disposition the dug [breast] from which they derive their origin”.

The beagle looked even less like the original shepherd’s dog. “Its ears are long and entirely pendent; the softness, the tractability, the timidity of this dog”, proclaimed the Encyclopaedia, “Buffon considers as many proofs of its degeneracy, or rather of that perfection which it acquires by culture, and living among a civilised people”.

Some degenerate beagles just lazing around. Image Credit: Brodo, Wikimedia Commons, 2006.

Not everyone agreed with Buffon’s assertion that the changes occurred because of civilisation. James Anderson, in one of his monthly issues of Recreation in agriculture, natural-history, arts and miscellaneous literature (London, 1799-1802) dismissed Buffon as a bit daft for thinking that all varieties of every species might descend from common stock.

From a post-Darwinian perspective, we can understand the sense in Buffon’s argument, but Anderson had legitimate grounds for complaint: that Buffon had failed to provide good evidence. Indeed, Anderson pointed out that dogs were not a particularly good example and objected, specifically, to Buffon’s claims that climate and geographic region could transform an animal. A British dog might, for example, accompany his owner to the other side of the world, but would remain the same. Anderson was adamant that a bull-dog in England showed the same obstinacy in ancient Rome as today and that a greyhound’s litter in Norway could not suddenly become bull mastiffs! A dog possessed the same qualities at birth that it would possess throughout life, no matter its location. While a dog’s temperament might change—becoming leaner, fatter, healthier or sicker—it would never become another breed.

Unless… a female mated with a male of a different breed, resulting in an “impure race” that had the qualities of both parents. This, then, was how Anderson explained breed variety. Different breeds were in fact artificial creations. There was no such thing as a natural dog. Although Buffon had thought that wild and domestic dogs were so distinct that they were unable to reproduce, surgeon John Hunter demonstrated through a series of experiments that such matings frequently resulted in offspring. According to Anderson, the beagle only differed from a bull mastiff because of selective breeding on the part of humans rather than its climate or food.

The debate itself reflected several strands of Enlightenment thought. Throughout the eighteenth century, scholars set up dichotomies between civilisation and nature. Civilisation was alternately good (allowing reason and order to flourish) and bad (resulting in artifice, corruption and inferior stock). In an increasingly imperial age, the implications went beyond how people saw their pets. Such ideas reflected the way that the British and French encountered the natural world and other cultures across the globe. Whether one thought civilisation was good or bad, however, one thing remained the same: the world could only be understood in terms of hierarchies, classifications and dichotomies.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800), as well as teaches a course on “Defining Boundaries: Natural and Supernatural Worlds in Early Modern Europe”. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. Follow her on Twitter, where she tweets as @historybeagle.

June 20, 2013

Avoiding the Crowds

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

I recently accompanied a group of alumni from Vanderbilt University on a cruise that started in Cannes and ended in Venice, with lots of stops on the way (at one point, we were in four different countries in four days). In Florence, I left the group and went to the Archaeological Museum, where only a few visitors were there to admire the gorgeously displayed Etruscan artifacts, and to the Bargello Museum, almost as deserted, where I visited Donatello’s David (the 1440 version) twice because one look isn’t enough. In Rome, a group went with me, and we strolled in the small streets between Piazza Venezia and the Pantheon. (If we’d had time, we would have gone up the Aventine Hill instead—next trip.)

If you find yourself in the Adriatic and want to flee the crowds, there’s an entire site off the beaten path: the Greek and Roman town of Butrint, near Saranda, Albania.

Substructure in the Roman bath, with marsh water

You can read more about this site, an important port for the Hellenistic Greeks and later the Romans, here. Briefly, the Romans took over the Greek settlement of Buthrotum and then abandoned it when the marsh rose into the town. Much of it still lies unexcavated under forest. The marsh means lots of mosquitoes, which in turn means lots of swallows that are so effective that I don’t think anyone in our group was bitten. There are also snakes, but our guide was the only person who saw any, and she was nice enough not to mention it until we were back on the road.

Low door (to slow down attackers) with a frieze of a lion devouring a bull’s head

Inside a guard tower

Are they reading the inscription?

The shadows of the trees make it hard to take a good shot of the mosaic

We were the only group there on a beautiful June day. Saranda is just six miles from Corfu, and the authorities hope that as more of the site is excavated, tourism will increase. If you want to visit in peace, go soon!

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.