Holly Tucker's Blog, page 67

May 14, 2013

Secrets of a Roman Sewer

Recently I attended a fascinating lecture by Professor Mark Robinson of Oxford University on the subject of Roman organic waste.

Excavating the Ancient Sewers of Herculaneum was part of the British Museum’s fabulous ongoing exhibition Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum. For a fuller account, please read my History Girls blog post. But here are seven fascinating facts I took away with me:

1. An enormous septic tank – the so-called Cardo V septic tank – at Herculaneum produced the largest amount of organic matter recovered from any Roman site to date. The excavation also produced 170 crates of solid material like builders’ waste, pottery, coins and jewelry.

2. The contents of the Herculaneum septic tank would have been periodically emptied, presumably by slaves. The utterly disgusting muck was an extremely effective fertilizer and was probably sold to farmers at great price.

3. However, pottery remains suggest the sewer had not been emptied for up to fifteen years before the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, which of course destroyed Herculaneum. (The carbonizing effect of the famous pyroclastic surge did not affect the material in the tank.)

4. The contents of this long septic tank contained a variety of foods that had passed through the systems of Herculaneans. And we also have kitchen waste like eggshells, animal bones and olive pits. From this we get a mouth-watering catalogue of what they ate: eggs, chicken, fish, shellfish, green leaf vegetables, berries, grapes, figs, dates, lentils, beans, millet for porridge, olives, plus black pepper, poppy seeds, dill and coriander for seasoning. Bones of small birds suggested the beccafico or “fig-eater” bird (like the one in the fresco above, from a villa near Herculaneum) was on the menu. We know from poets like Martial that Romans enjoyed eating these little birds.

5. The Romans thought wet and smelly things should be restricted to one area. This is why so many latrines are found in kitchens, and why so much kitchen waste was found in the sewers and septic tanks.

6. Not a single sea-sponge turned up in the mass of organic matter from the Cardo V Septic Tank. This suggests that citizens of this part of Herculaneum probably didn’t use the notorious sponge-stick as a bottom wiper. Scraps of calcified fabric in the organic matter suggest their version of luxury toilet paper was more probably cloth. Presumably the scraps would be washed and re-used, like a baby’s diaper. This task no doubt fell to an unhappy slave.

7. A preponderance of oil lamps in the septic tank suggests that some Romans might have read on the seat of ease. As it says in the Bible “There is nothing new under the sun.” (Eccl 1:9) Or maybe it should be: “There is nothing new where the sun don’t shine.”

Caroline Lawrence (left) tries hard to be scholarly about ancient Rome but gets unduly excited by food, jewellery, poop and suchlike. Just as well she writes for kids and kids-at-heart. She will be giving two talks of her own at the British Museum on 27 and 31 May, 2013. For more information, go to Animals in Pompeii & Herculaneum OR Children in Pompeii & Herculaneum.

And for more info about Caroline’s history-mystery books, go to www.carolinelawrence.com

Caroline Lawrence (left) tries hard to be scholarly about ancient Rome but gets unduly excited by food, jewellery, poop and suchlike. Just as well she writes for kids and kids-at-heart. She will be giving two talks of her own at the British Museum on 27 and 31 May, 2013. For more information, go to Animals in Pompeii & Herculaneum OR Children in Pompeii & Herculaneum.

And for more info about Caroline’s history-mystery books, go to www.carolinelawrence.com

May 13, 2013

The famous surgeons of St Bartholomew’s Hospital

St Bartholomew’s hospital has provided care for up to four hundred City patients since its founding in 1123 but it was during the eighteenth century the hospital moved from a treatment model based on medieval nursing to that of an active working hospital with many different types of medicine and medical science going on within its vast compound.

The main entrance to the hospital contains two enormous murals by William Hogarth, who had been born in Bartholomew Close. Hogarth found out that the trustees were going to use the Venetian artist Jacopo Amigoni to decorate the entrance hall to the hospital, and so offered to work for nothing rather than have foreign art in an English hospital. The two pieces, Jesus at the Pool of Bethesda, and the Good Samaritan were painted in early 1737 in what Hogarth believed to be a Classical style, but they already reflect in detail the attention to reality that was to become to apparent in his later work. Not for him the glossing over of ulcerated legs, distended bodies and disability, and only Jesus himself escapes from deformity and suppuration.

The famous surgeons of Bartholomew’s hospital during the eighteenth century include Percival Pott, who was fascinated by occupational diseases and made the first identification of occupational cancer: scrotal cancer in teenagers who had worked as chimney-sweeps. Pott was succeeded by his famous pupil John Hunter, born in East Kilbride, Scotland in the late 1720s. When he was 21 after an early career as a cabinet-maker he arrived in London to visit his older brother William who had established himself as a teacher of anatomy in Soho. John decided he would stay and learn to be a doctor, and soon showed great talent. He made important steps forward on identifying the existence and mechanism of the lymphatic system and in the late 1760s attempted to infect himself with venereal disease, a subject which on the time he was regarded as an authority. Popular belief dictated that any venereal disease was just milder or more severe versions of the same thing, a belief which Hunter agreed. After managing to infect himself with both gonorrhea and syphilis at the same time, during an inoculation experiment he discovered they were indeed, separate things.

The contribution of the Hunter brothers were working at the very beginning of the debate about life itself which would play out in the late 1700s in the purpose built ‘theatre’ of Bart’s. New philosophies such as Deism and Mesmerism, sat awkwardly with Britain’s established Protestant religion. One Bart’s doctor who attempted to resolve this seeming gulf was John Abernethy (pictured). Born just inside London Wall in Coleman Street in the City and a pupil of John Hunter, he went on to become the resident surgeon at Bart’s. He was a charismatic speaker and an eccentric character who mixed his ideas with very down to earth advice, which was delivered bluntly. A lady came to him complaining of low spirits, to which his advice was ‘Buy a skipping-rope’, and when the Duke of Wellington arrived out-of-hours in Abernethy’s parlour, Abernethy enquired as to how he had managed to get into the room. ‘By the door,’ the Duke said. ‘Then,’ Abernethy told him, ‘I recommend you make your exit by the same way’.

Abernethy was surgeon during a time when one might not only be a doctor, but an authority upon the science of life itself. The existence of the soul, or spirit as separate to the mind was a hot potato and one considered seriously by one of John Abernethy’s lesser known pupils: Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In 1811, unhappy in his hasty marriage Shelley hugged the heels of his cousin Charles Grove around the wards of Bart’s Hospital in the afternoons after attending Abernethy’s lectures in the mornings. He had just published his pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism, signing off ‘Thro’ deficiency of proof, AN ATHEIST’, resulting in his expulsion from Oxford. Although he was quite clearly kicking against the idea of an omnipotent and omnipresent God, Shelley had not yet answered for himself ‘The Vitality Question’. What is life? At Bart’s, amongst men who dealt with the creation and snuffing out of life all the time, perhaps he thought he would find an answer. He concluded only that ‘Life, and the world, or whatever we call that which we are and feel, is an astonishing thing.’

Shelley’s time at Bart’s isn’t reflected most keenly in his own work though, but in that of another. During his time at the hospital, he had begun his love affair with Mary Godwin. They married in St Mildred’s church, Poultry soon after his first wife drowned herself when he abandoned her. Mary Shelley would become a ‘silent but devout’ listener to Shelley in his talks with Lawrence. She would hear about surgery and dissection and experimentation upon dead and living bodies as well as the latest theories for how the mind and the soul occupied the body. Galvinism, the crude beginning of understanding about the body’s nervous and electrical impulses and the new experiments on ‘re-animating’ corpses would also be something she became familiar with, and all in her mid-teens in the throes of a love affair. This intense period of first love, mixed with hero worship and both the philosophy and the grim reality of medicine would combine in her novel published in 1818, Frankenstein.

May 9, 2013

Fun with pigs

By Helen King

Finally, I understand what it is about dissection…

Regular readers will know that, among other things, I’m a visiting professor at a medical school. As a recently-founded medical school, this one does not teach through human dissection. Instead, students learn their anatomy through books, computer simulations, models, and ‘surface anatomy’. The rationale is not just about the difficulty of getting enough cadavers coupled with the recent availability of good online materials, but also about the purpose of training; many of these students will go into general practice after qualifying, and here the ability to understand what patients are feeling – to sympathize and to empathize - will be more important to them. Those who want to specialize in obstetrics, anaesthesia, surgery and so on will in any case be doing further training in which dissection will play a part.

Every year, my fourth-year students present to their fellow students on what they have learned in their Special Study Unit. Mine learn the history of dissection; the roles it has played in education, the objections made to it over time by the public and also by medical practitioners. For example, is studying a dead body the best way to prepare someone to study a living one? Does dissection ‘coarsen’ the mind, and reduce the physician’s ability to engage emotionally? Or is this all about gaining some sense of professional distance? But is that distance really such a good thing?

As part of their assessment, the students write a reflective journal. This is mine! This year, at the end of their excellent presentation of summaries of five periods of medical history, the students had a surprise for their peers: a dissection. Not, of course, a human one. They had bought a pig, or at least the non-edible parts which could be acquired cheaply, supplemented by the contents of the freezer of one of the students. Gloves, plastic aprons and scalpels were issued, the sharps disposal box put on the table, and the students in the audience were invited to get started.

The ensuing scene recalled many of the periods of medical history we’d studied. First, having a pig reminded us of Galen’s famous second-century AD vivisection, in which he showed how a pig’s squeal is generated – and stopped. The presence of pig organs raised many questions for the students about how far human and animal are comparable; questions that go back at least to Aristotle, that great comparative dissector of animals, in the fourth century BC. Then, the sheer enthusiasm of the students to be close to the dissection, to get involved, recalled the notes taken by a student present at Vesalius’ dissections back in 1540; he talked about them becoming positively over-excited, jostling each other for space, pushing so much that they couldn’t feel the beating heart that he invited them to touch. And finally, the enthusiasm with which our students brought out their phone-cameras, and took pictures of each other with the pig’s head, made us think of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century medical students who had themselves photographed with ‘their’ med school cadaver, and then sent the pictures to their family and friends.

The transgressive nature of dissection, the difficulty of seeing properly when it is basically quite messy, the bonding effect of working together – as a result of what my students did this year, I feel I have probably learned as much as they did!

May 8, 2013

The Jeffers Petroglyphs: Historical Treasure in an Unexpected Place

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

The Upper Midwest of the U.S. is not well known for its archaeological treasures, and it’s easy to see why. The region has utterly transformed over the past 200 years through the loss of 99 percent of its tall grass prairie, the felling of most of its original forests, and the harnessing of much of the land for agriculture.

A turtle carved into the rock at the Jeffers Petroglyphs site.

But each spring’s snow thaw in Minnesota brings the reappearance of one of the nation’s most beautiful historic sites. Near the town of Jeffers in the southwestern part of the state is a remarkable collection of Native American petroglyphs — rock carvings — the oldest of which date back more than 7,000 years. Managed by the Minnesota Historical Society, the Jeffers Petroglyphs site and visitors center is open from May through September.

For thousands of years, native people from a wide area have been visiting this site on spiritual pilgrimages and to leave carvings on portions of a 23-mile-long outcropping of red quartzite, a bedrock deposit more than 1.6 billion years old.

The visitors center is worth seeing first. An almost wordless multimedia presentation offers scenes of the petroglyphs site in centuries past, showing the activities of native visitors during night and day. Small exhibits cover prairie ecology, the cultural significance of the bison, and the original uses of various Indian artifacts.

To view the petroglyphs, you follow a trail through a restoration of native prairie, converted from farmland 40 years ago. It includes the prairie bush clover and other examples of endangered grasses and plants — a total of more than 200 species. A few minutes of walking brings you to the petroglyphs.

Here, with the big sky above, the smell of the prairie in your nose, and the sight of acres of sloping red quartzite at your feet, you really feel as though you are in a place of spiritual importance. It’s how you would imagine a visit to Stonehenge feels — a site in the middle of nowhere that conveys a sense of being at the center of things. A roped trail leads you across the rock, which is noticeably scratched by the passage of glaciers. The degree of cloudiness in the sky, angle of the sunlight, and wetness of the rock determine which of the approximately 2,000 carvings at Jeffers are most easily seen at a given time.

Appearing between patches of lime-green and black lichen, the rock carvings depict thunderbird tracks, buffalo, atlatls, turtles, deer, hands, human profiles, and narratives that might tell tales of hunts. Because of the hardness of the rock, the larger and deeper carvings must have required extended or repeated visits by their makers. Nobody knows which Native American groups made the earliest carvings. In recent centuries, members of the Dakota tribes inhabited the area, and it’s possible that the Ioway, Otoe, and Cheyenne did as well. The site and its carvings still carry spiritual significance for Native Americans in the region.

On the way back to the visitors center, you can follow the northern loop of the trail, which passes by buffalo rubbing rocks, large quartzite boulders burnished to a glassy sheen by the rubbings of countless bison over 10,000 years.

This unforgettable site is too little known, even among those who live in the Upper Midwest. It offers a glimpse into the minds and hearts of people who left a permanent imprint on the land they loved.

Recommended reading:

Callahan, Kevin L. The Jeffers Petroglyphs: Native American Rock Art on the Midwestern Plains. Prairie Smoke Press, 2004.

Kennedy, Frances H. (editor). American Indian Places: A Historical Guidebook. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008.

May 6, 2013

Drunk on Horse Milk: Fermented Koumiss

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonder & Marvels contributor)

Amazons, those fabled women warriors of the steppes, were working mothers too busy to breastfeed. According to the ancient Greeks, they nourished their infants with mare’s milk. Since Homer, nomadic tribes from the Black Sea to Mongolia were known as “mare-milking Scythians.” That notion was exotic enough, but the Greeks would have been surprised to learn that the babies’ milk contained alcohol.

Milk from horses is nutritious but because of its high lactose content raw mare’s milk is a strong laxative. It requires fermentation to be a viable source of nutrition, even for babies. During fermentation the milk is agitated or churned like butter. The lactobacilli bacteria acidify the milk and yeasts create carbonated ethanol. The result is mildly alcoholic koumiss high in calories and vitamins. (Koumiss is similar to kefir, a fermented, less alcoholic milk drink of the Caucasus.) Scythian men and women preferred a stronger alcoholic punch than the drink given to babies. (One ancient Amazon’s name translates as “Drunkard.”) The nomads discovered how to enrich fermented milk by the process now known as “freeze distillation.” No strangers to snow, the nomads would allow the fermented milk to freeze, thaw it, remove the ice crystals, refreeze, and repeat until the desired alcoholic level was reached.

The Greek historian Herodotus (ca 450 BC) observed mare milk churning on a large scale among the settled Scythians on the Black Sea. They poured the milk into deep wooden casks, then stirred vigorously as it fermented. What rose to the top was drawn off and drunk. The early European traveler William of Rubruck, who trekked across the steppes ca AD 1250, watched the same process: “As the nomads churn the milk it begins to ferment and bubble up like new wine.” He sampled the effervescent beverage and found it pungent and intoxicating. “Koumiss makes the inner man most joyful!” Smaller batches of koumiss were fermented in leather bags by families on the move. In Inner Asia, the custom was to hang the sack where passersby could periodically punch the bag to agitate the koumiss. Koumiss is a favorite drink from the Black Sea to western China.

How ancient is koumiss? Historical linguistics and archaeology provide clues. The three most ancient alcoholic beverages are mead (fermented honey), kvass (beer), and koumiss. Kvass and mead have cognates in Proto-Indo-European languages, while koumiss derives from the ancient Central Asian Turkic language family. So koumiss originated along with the domestication of the horse on the steppes more than 5,000 years ago.

Lipids from horse milk can be identified on artifacts in ancient burials. Bowls containing residue of mare’s milk have been discovered in Botai culture dwellings of about 3500 BC in Kazakhstan. These people were among the first to tame wild horses. Evidence for fermented mare’s milk is also found in the graves of Scythian men and women. Special utensils for beating koumiss and drinking vessels with traces of horse milk are common grave goods. The famous Golden Warrior of Issyk (Kazakhstan) was accompanied by koumiss beaters and bowls that held traces of mare’s milk. In the grave of the tattooed “Ice Princess” (Ukok, Russia) archaeologists discovered a wooden stirring stick in a cup decorated with snow leopards. Inside the cup was the residue of koumiss that would sustain her in the Afterlife.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

April 29, 2013

Masturbation and the Dangerous Woman

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

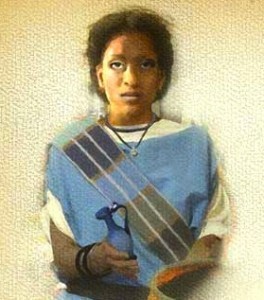

Before masturbation. Mlle Chxx aged 15 years (1836). Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Remember all those playground stories about masturbation causing hairy palms and blindness? Those tales go way back. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, much ink was spilled on the devastation that masturbation would cause. Men’s frequent self-pleasuring would destroy the fibres of their penis, and the masturbator would become effeminate, weak, infertile and leaky. The female masturbator, however, was discussed less often. But for a woman, there were two greater dangers: that she might lose control of her body and that her husband might lose control of her.

The anonymous author of The Ladies Dispensatory (1739) recounted two cautionary tales of masturbating women. One young woman abused herself between the ages of 14 and 19, resulting in a furor uterinus (nymphomania). During increasingly violent fits, the woman undressed and violently attacked any man nearby. She soon after died, at which point doctors and surgeons anatomized her. They found that her clitoris had swollen abnormally and that her blood appeared especially sharp and corrosive. In the other story, a young woman discovered masturbation at the age of eleven, with her mother’s chambermaid at the age of eleven. Seven years later, she had developed a clitoris so large that she appeared to be a hermaphrodite. The doctors attributed this to clitoral relaxation. Through masturbation, both young women became ‘masculine’ and sexually aggressive, with uncontrollable bodies.

Taken to its logical conclusion, the body of a female masturbator might even create its own offspring, independent of human action. Physician G. A. Douglas argued in his book, The Nature and Causes of Impotence in Men, and Barrenness in Women (1758), that false conceptions could be caused by self-abuse. He suggested that women needed vaginal stimulation in order to make an egg descend. If a woman used “those shameful implements” to stimulate herself, she would produce an egg that would remain unfertilised and grow so that it resembled a pregnancy. Women, he warned, “should know this and tremble”. Given the loss of bodily control, it is no wonder that female masturbation was seen as dangerous. Masturbation resulted in inverted social and sexual hierarchies: men became womanly and women became manly.

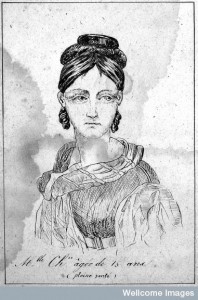

After masturbation. Mlle Chxx aged 16 years (1836). Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

However, this was not the only reason why the secret vice of women “strikes at the very root of fertility.” Most importantly, according to The Ladies Dispensatory, a wife who masturbated might be beyond her husband’s will. The fear was that barrenness would result from a woman’s “Indifferency to the Pleasures of Venus, and in Time a Total Ineptitude to the Act of Generation itself.” For example, one young lady wrote a letter to the anonymous author of Onania (1716) that she had learned masturbation at boarding school. She married at seventeen and produced three children within two years. Then her husband died and, for two more years, she eased her desires and comforted her loneliness through excessive masturbation. She became concerned three years into her second marriage when she had failed to produce any children. The physical symptoms included weakness, a bearing down of the womb and a pain in the back. Worst of all, though, she was not interested in “the Act of Procreation.” She complained that she had “very little or no Pleasure in the Act, which I am thinking may be as much as anything, the Reason I can have no children.”

The author of The Ladies Dispensatory included the case of a young woman who had been married for four years, from the age of seventeen. She masturbated regularly from the age of eleven and continued after marriage, even in preference to her husband. Her womb was so slippery that her periods had stopped and she had not yet become pregnant. The authors of Onania and The Ladies Dispensatory sympathised with the plight of the husband: “How must it grieve them [the women] when they find the ends of it [marriage] unanswered, and have room to charge their ineptitude to Procreation on their own fault? Both Husband and Wife perhaps may be passionately desirous of Issue, and the good man may think it a Defect in himself.” Through her lack of self-control, the masturbating woman brought disorder to the marital relationship. The husband, unaware of his wife’s activities, blamed himself for the failure to conceive and was unable to keep her sexuality under his control.

Overgrown clitorises? False pregnancies? Sterility? Failed marriages? The twentieth-century playground fears about masturbation had nothing on the eighteenth-century ones!

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800). She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog and edits The Recipes Project. She tweets as @historybeagle.

April 20, 2013

To Brand or Not to Brand

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

My writing career has been somewhat anomalous, not because I came to it lateish (in my thirties—younger than a lot of authors), and not because I continued to work full-time and raise a family for the first twenty years of it—most women and many men who write have combined writing with a paying job and/or a family. No, it’s because I write all over the map.

In this day of “branding,” authors are cautioned to stick to one genre, and authors of books for young readers are advised to write for only one age group. The thinking is that if, say, a twelve-year-old loved your dystopian zombie romance, she’ll be disappointed if your next book is a high-concept action thriller, and might resolve never to read anything by you again.

But that monolithic kind of writing career has never appealed to me. My first seven books for young readers were nonfiction. While all had something to do with the United States—history, biography, travel—they were aimed at different age groups (from second to sixth grade) and were published by three different companies.

Then I wrote a biographical novel set in medieval Byzantium, followed by a hi-lo book on the Trail of Tears, then a ghost story, two nonfiction histories (both of ancient European civilizations), a time-travel novel, a four-book detective series, a historical fantasy set in Iron-Age Greece, and a historical novel set in Bronze-Age Greece. (You can see a complete list here, if you’re interested.)

Next will be a Cinderella retelling. A murder mystery set in the ancient world is now circulating among editors, I’ve sent my agent a nonfiction manuscript, and I’m wrapping up a retelling of an ancient myth, set in the modern day. Suggested reading age varies between age nine to twelve and age “12 and up,” although I’ve heard from readers who are seven years old, as well as from plenty of adults.

I’ve been told that a career like mine probably wouldn’t be possible today. And a friend who wrote a multiple-award-winning historical novel said that her agent and her editor both strongly recommended that her next book be historical fiction as well. Maybe she would have wanted to write another historical novel anyway, but what if she hadn’t? Would it have damaged her career to head off in another direction?

Maybe so. And maybe my own sales figures would be higher if I could be easily pegged as a writer of this or that genre for this or that age group. Of course I want people to buy (and read!) my books, but if income were the prime consideration, I would have chosen a career as a corporate lawyer, or I would have sought a tenured teaching position. But I never went to law school and I never went for tenure, and I’m glad I didn’t do either. I’m also glad I’ve always written what interests me without feeling constrained by the market, and I’ve told the stories that I want to tell. If my sales suffer for it—well, so be it. I’d do it again.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and the Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). Forthcoming from Harlequin Teen in July, 2014 is The Stepsister’s Tale. She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

April 18, 2013

A Labyrinth of Kingdoms

By Pamela Toler

Sometimes a book grabs you by the throat and won’t let you put it down. I recently experienced that with Steve Kemper’s A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles Through Islamic Africa. I got so wrapped up in the story that I broke my long-standing rule about traveling with hardcover books because I wanted to finish it. I read on the plane. I read whenever there was a pause in vacation activities (and sometimes when there wasn’t). I read on the train from the airport and was so engaged that I almost missed my stop.

In the Victorian era, European explorers made their way through Africa in the name of “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization”. The adventures of Burton, Stanley, and Livingston are well known. Those of German scientist, historian and linguist Heinrich Barth are almost forgotten. Kemper tells the story of Barth’s five-year, 10,000-mile journey through North and Central Africa.

The British Foreign Office hired Barth in 1849 as the lead scientist for an expedition through the central Sudan. When the other members of the expedition died, Barth traveled on alone. Beset by failed supply trains, bandits, avaricious rulers, anti-Christian violence, desert storms, floods and fever, Barth nonetheless wrote detailed accounts of everything he saw. Unlike other African explorers, he showed a deep respect for the peoples and cultures he encountered.

A Labyrinth of Kingdoms is a fascinating account both of one man’s journey and of African cultures on the eve of European expansion. Like Barth himself, Kemper turns his attention beyond the narrow concerns of European imperialism and looks at the broader context of Islamic Africa. He gives the reader brief histories of the kingdoms Barth traveled through, including the fabled city of Timbuktu. He compares Barth’s adventures and observations not only to those of the British explorers who were his contemporaries, but to the great Islamic travelers of the past who wrote about their experiences in the same regions.

Barth’s story is equal parts adventure and scholarship. Kemper treats both with a sure hand.

(This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers)

April 15, 2013

Ivory Bangle Lady

Sometimes I miss Rome so much I think I might die.

They found her body in York. Her bones show she died young, aged around 19. She was probably beautiful, for her skull is symmetrical and her teeth were good. Isotopes (trace elements) in her molars prove she came from a hot country, almost certainly Africa.

This mixed-race woman died over 1500 years ago in Roman Britain, and was first unearthed in York a century ago. Recently, archaeologists at the University of Reading, UK have been examining her all over again using the latest advances in forensic science.

As well as studying her bones, they have been scrutinizing her method of burial and grave goods.

She was buried in a stone sarcophagus, a mark of wealth.

Another clue to her wealth was the beautiful blue glass jug found with her. A futher clue to her wealth (and beauty?) was a mirror found near her skeleton. And not just any mirror, but a glass mirror, exceeding rare for Roman times.

She also had jewelery in the tomb: a locket (or her childhood bulla?), earrings and a necklace with beads. But more than all of these, she must have loved her bangles. She had one made of “magical” jet, one made of blue glass, and some made of exotic elephant tooth: ivory.

For this reason, the archaeologists nicknamed her Ivory Bangle Lady.

Not only was she of mixed-race, beautiful and rich, but she was certainly literate and probably a Christian. We know this from a beautiful piece of bone with the words: SOROR AVE VIVAS IN DEO “Greetings, sister! May you live in God.” Or does it say, “Farewell, sister! May you live in god.”? The Latin word ave can mean both.

Was it part of a box? Did she have it when she was alive? Or only after death?

What was in her blue glass jar? Wine? Perfume? Honeyed milk?

And what was she doing in Eboracum – York – so far from North Africa or Rome?

As the author of 20 history-mystery books set in the Roman period, I was invited to write stories about some of the bodies from Roman Britain. I had to use the clues of bone evidence and grave goods and then add my imagination and knowledge of Ancient Rome.

Now, thanks to an exciting new website, you can do what I did. Romans Revealed, geared at school children aged 8+, allows you to examine the graves and bones of the Ivory Bangle Lady and three other individuals found in Roman Britain in the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE. You can hear modern scientists and archaeologists (like Dr. Hella Eckhardt from the University of Reading) discuss the significance of the grave goods and isotope results. Best of all, you can then make up your own stories about the lives and deaths of the four individuals chosen: Brucco, Savariana, Piscarius and Julia Tertia, the Ivory Bangle Lady.

Caroline Lawrence is the author of the best-selling Roman Mysteries series for kids. She and archaeologist Dr. Hella Eckhardt will both be present at the Museum of London on Thursday 25th of April to help launch the Romans Revealed website. Romans Revealed is supported by the Runnymede Trust and generously funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council and the University of Reading. A live launch will be hosted by the Museum of London and free to watch from 1pm GMT. Schools and individuals are invited to participate! Find out how by contacting elearning@museumoflondon.org.uk

April 13, 2013

A Blaze of Loyalty – Lucy Inglis

Britain’s only remaining illuminations (in the true sense) are in Blackpool, where they are associated with trams, tableaux and tackiness. But where did Blackpool, first lit up in 1879, get the idea for such a display? Georgian London of course.

The London illuminations of the 18th century are a small and almost forgotten element of the pageantry of the city. This is a shame, because the evidence is that they were splendid. An illumination was the mark of a celebration: some were city-wide with every public building lit up and many private houses, and some were specific to a family or business celebrating a birth or anniversary. The point of an illumination was to make a building look spectacular. Electricity has made such a process easier and now few major buildings are not lit up at night (albeit in a sickly sodium fashion), but without electricity how were such illuminations achieved?

The answer is with lamps and transparencies, as well as interior lighting. Small lamps, protected by hurricane shades (and made specifically for outdoor use by glaziers) were placed all over the buildings in specific arrangements meant to highlight the buildings themselves, or to pick out patterns such as initials, names or shapes. Transparencies were large painted sheets which would cover one face of the building, either to make it appear to be another building such as the Pantheon or to create the illusion that Britannia herself was sitting on the windowsill. Specialist firms of painters created these enormous transparencies and the accounts of some of them are truly remarkable. One of the largest London illuminations happened on the night of Friday, April 24th 1789 on the occasion of the celebratory procession to mark George III’s ‘recovery’ from madness, when every wealthy household and every public building was ablaze in a display of patriotic support.

‘We may safely affirm that the art and means of illuminating houses were never so compleat as at this day, from the improved form of the lamps and other circumstances, there never were in England more superb illuminations, than on the late and present occasions.’

The details of these illuminations must be set in context: there was little light pollution in Georgian London, and whilst individual houses bore lamps doubling as street-lights at night the streets were dark. To light a building for illumination would have been both extraordinary, and expensive (the newspapers estimated the April 1789 illuminations would have cost not less than ‘half a million’). The following are just some of the spectacles staged that Friday night.

‘Such a blaze of light was never seen in the City since its foundation. It will be the surest testimony for future historians to record how much KING GEORGE THE THIRD, was esteemed, and dwelt in the hearts of his people….The Horse Guards was illuminated with taste. The front towards the Park was particularly fine. The Army Office had pillars of green and white, supporting the crown and other emblems, very brilliantly illuminated….St James’s-street was as luminous as ever…White’s had a beautiful transparency from the Pantheon. In the centre; the King in his coronation robes, sitting in the Coronation chair at the Abbey: the transparency was studded round with lamps, and over and on each side were stars, circles and festoons….’

The descriptions of individual houses go on for a broadsheet page. Some noble house, such as that of The Earl of Uxbridge are singled out (he had Vivant Rex et Regina spelled out in enormous blazing letters across the front of his house). Josiah Wedgewood gets a mention for his tasteful transparencies. The city synagogues of Leadehall Street and Bevis Marks were also illuminated in a show of support for the king. Mr Stackpole’s house is Grosvenor-place was picked out for not only being illuminated outside, but for having thousands of candles burning in candelabra and chandeliers inside, making the place seem ‘ablaze with light’.

The illuminations were not only for noblemen, public buildings or the super-rich: everyone who could afford to take part did and even some of the little illuminations are described. These, of course, are my favourites. Mr Angell, Mr Schneider, Mr Neale and Mr Wheeler are all singled out for their fine displays at their shops or homes, although clearly on a more modest scale to the grander buildings. And finally, a mention revealing the creativity and individuality of 18th century London in a display that would look both modern and clever now: ‘Bland’s music shop, also in Holbourne, had a singular curiosity; it was a transparency of God Save the King placed in the windows’.

The newspaper was pleased to conclude that although the ‘crouds that paraded through the street till a very late hour were incredibly large…there seemed to be more of curiosity and wonder than of riot and mischief’.