Holly Tucker's Blog, page 68

April 9, 2013

Life and Death, Pompeii and Herculaneum

It’s all about the fear… when you never get to eat your daily bread.

I made it to Day 1 of the much-awaited British Museum exhibition on these two Roman cities – not because of careful planning but because, when I went online to book, that was simply the first day when slots were available. Getting in early meant getting a sense of it for myself, before the rest of the media and blogosphere came in with their reactions. So, how was it for me? Surprisingly good, and a fresh approach; before I went, I thought I knew about Pompeii (not least from the graffiti – e.g. ‘Chie, I hope your haemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than when they ever have before!’) – but I found much new here.

The space is laid out as the rooms of a large Roman home, with each object in the appropriate room. The organisers make the point that some activities didn’t have a room of their own: children were carried around the home with their parents (no ‘nursery’ or ‘playroom’), while sex happened pretty well anywhere, with a preference for the cubiculum, a dark room off a main room. The furniture from Herculaneum is astonishingly well preserved; tables, parts of a bed, a baby’s cradle. It is hard not to tell yourself stories about the people who would have used these objects. The ‘home’ includes the garden – superb frescoes of foliage and birds! – and here I felt that the air-con was a little lower, giving a sensation of the coolness that would have been expected in this precious bit of the countryside brought into the town. And the exhibition works with other senses too; there are faint sounds, birds in the garden, busy-ness from the street outside… It’s very clever, but doesn’t get in the way.

As for the objects, nobody wanted to get too close to the craftsmanship of the notorious statue of Pan getting frisky with a goat. Funny, that. I loved this – it really made me laugh, and made me wonder if that’s how its original viewers would have reacted. Pan is, after all, a goat beneath the waist, so why not fall for a – er – total goat? The dormice jar – for fattening dormice for consumption – is very special, but here gets extra impact by being in the ‘kitchen’ near to a portable oven that Apicius, the Roman cookery writer, recommended as ideal for cooking this delicacy. It made me wonder – is this indeed the room where the jar would be kept, with scraps of food being put into it (basic recycling)? Do we know this, or would it have been kept where the eating happened? The kitchen also has the pictured carbonised loaf of bread from Pompeii.

After an hour or so sharing the lives of these people, the impact of their deaths – the focus of the final room of the exhibition, alongside a time-line of the events after Vesuvius erupted – is very real. A case displays the things people took with them as they fled: money, jewelry, but – poignantly – good luck charms and statues of deities who were associated with luck. We viewers are invited to think about what we’d take with us, if we had to run – but the message is clearly that it doesn’t make any difference.

And I think that’s my abiding impression: life is uncertain. The excellent short film that is shown on the way into the exhibition concentrates on the links between past and present, juxtaposing ancient frescoes and film of Italians today shopping and entertaining. At one point the black line of the coast, on a map showing where the two cities were in relation to the volcano, transforms into an animated seismograph. The people of these two cities had lived through lots of little earthquakes, but didn’t understand that these were warnings of the eruption. Someone even made an image of some buildings shaking – it’s chilling to see it as part of this exhibition. Death was just around the corner. Nobody got to eat that loaf.

On 18 June, a tour of the exhibition will be shown live in selected cinemas: see

http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on...

April 8, 2013

Charles Dawes: Vice President, Nobel Winner and Musical Hit Maker

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Barry Manilow, Van Morrison, the Four Tops, Cass Elliot, Isaac Hayes, Bing Crosby and Nat “King” Cole all owe a lot to a now obscure United States vice president and Nobel Peace Prize winner named Charles Dawes. Those musical artists, as well as dozens of others, recorded a song that the American statesman dashed off in a single sitting decades earlier. Dawes, who had a background in banking and law with no formal music training, never suspected that his tune would someday reach the very top of the pop charts in the U.S. and U.K.

Charles G. Dawes

The tale of that hit song, “It’s All in the Game,” begins in Marietta, Ohio, where Dawes was born in 1865. Long interested in music but discouraged by his parents from pursuing it as a profession, he taught himself passable skills in playing the piano and flute. He passionately attended concerts of visiting artists in Marietta and kept a diary of his impressions of their performances. Dawes eventually established himself as a banker in Illinois, but he never lost his love of music, helped form the Chicago Grand Opera company, and frequently sat at the keyboard to pass his idle minutes.

During one of those interludes at the piano in 1911, Dawes sketched out a tune that he liked very much. He soon returned to the piece and gave it a solo part for violin. His friend, the violinist and fellow Mariettan Francis MacMillan, heard the melody and fell in love. “It’s just a tune that I got in my head, so I set it down,” Dawes explained to MacMillan. “I never gave the thing a name. If you want it you can have it. It has served its purpose as a diversion for me.”

MacMillan made the most of that invitation. He sold it to a publisher, and before long Dawes’ piece, now titled Melody in A Major, was a light-classical hit. “I was walking down State Street and came to a music shop,” Dawes wrote of his discovery of the fame of his creation. “I saw a poster size picture of myself, my name plastered all over the window in large letters and the window space entirely filled with the sheet music.” Phonograph recordings by such artists as the violinist Fritz Kreisler sold by the tens of thousand.

Dawes’s Melody in A Major, in an arrangement for pipe organ.

In the years that followed, as Dawes became the first director of the U.S. Bureau of the Budget, formulated a plan for Germany’s payment of reparations to the Allies, was elected vice president on the Republican ticket with Calvin Coolidge in 1924, and shared a Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 for his work enabling Germany to handle its weighty war reparations, the Melody in A tailed its creator in performances by marching bands, string quartets, and a variety of often ill-fitting musical ensembles. Dawes grew weary of it. “If it had not been fairly good music I should have been subjected to unlimited ridicule,” he lamented.

The cacophony had quieted by the time Dawes died in 1951. Later that year, however, Melody in A began a new life as a hit pop song. Songwriter Carl Sigman — who would later write lyrics for “What Now My Love,” “A Day in the Life of a Fool,” and “Ebb Tide,” — got the tune stuck in his head and adapted it for “It’s All in the Game,” a song about the vicissitudes of love. When crooner Tommy Edwards recorded it first, the song climbed to eighteen on the pop charts. Edwards covered the song again in 1958, and this doo-wop version hit number one and became one of the defining songs of the 1950s. Recordings by a slew of pop, soul, jazz, R & B, and easy-listening artists followed and have continued unabated.

Dawes is the only U.S. vice president and Nobel prize winner to earn a credit for a hit song. At the end of his life he had at last given up on music. “Not long ago I tried to play ‘Tea for Two,’ which I used to play a lot,” he wrote, “but I won’t try it again.” He could no longer hear the musical overtones.

Sources:

Timmons, Bascom N. Portrait of an American: Charles G. Dawes. Henry Holt and Company, 1953.

Was, David. “Tracing the History of a Song: ‘It’s All in the Game.’” Day to Day program transcript, April 5, 2006.

April 6, 2013

Imagine a world without the arts

by Stephanie Cowell

“The world will be saved by beauty,” Dostoevsky once said. I try to remember that when I find the life of a professional writer difficult. Before writing I was a classical singer and for a brief time an actress and I have spent many hours (likely weeks if you add up a lifetime) complaining about the angst of a life in the arts…the insecurity of creating art, the insecurity of selling it. Oh the hours I have wasted!

My mother (who was an artist) used to say, “Art is cake. People buy necessities first.” She was a child of the Depression and what she spoke was true. Most people will not buy a book if they need food – though I despair if anyone gives me clothes instead of books or music for a birthday.

We complain most about making our work known. Without huge amount of publicity and media, few people will know of the existence of a work of art, few people will hear of an artist or a performance or a writer. Sometimes a work slowly becomes known by its own virtues. Moby Dick sold a handful of copies at first as did Walden. But if Jane Austen had given up trying to publish an early version of Pride and Prejudice, we would not have it today. Most art makes little money; Shakespeare sold Hamlet for probably ten pounds, enough to support a family in very modest circumstances back in 1602 for a few weeks.

I cannot imagine a life without the poems of Gerald Manley Hopkins, whose work was never published in his lifetime and had perhaps seven readers before his death.

So the other day when my friend and I were bewailing the difficulties of the artist, we suddenly began to imagine a life without any of the arts, if it were all sucked away in a sort of black hole.

We saw ourselves returning to a house without any books on the shelves; no one would ever again live through the worlds of Charlotte Bronte or John Steinbeck. The words would all disappear from my many editions of Shakespeare. There would be no movies in the theaters or DVDS; Star Wars would not exist nor A Room with a View. We would live our lives without concerts, opera, without the symphonies of Mozart, the quartets of Beethoven, the folk ballads and church music. Handel’s Messiah would never be heard again. Museum walls would be blank; no one would know the work of Claude Monet, medieval Arabic art, a Greek statue. Paintings by my parents and husband would fade from my walls. Across the world, all the great architecture from the Taj Mahal to the great Italian and English cathedrals would vanish into the air.

So I returned to my new novel in progress because I loved the story, and without pouring my spirit into it, it would not exist for me, for itself, for others. I think with a painful shudder of how wars or floods have desecrated art. In Florence’s Santa Croce, they tried to piece together fallen fragments of the Cimabue cross damaged by the flooding Arno. Can we recreate the Buddhas of Bamiyan?

My friend and I thought for only one terrible moment about such a world. It would be a wasteland. And yet over so many dinners we have complained, all my friends and I.

“The world will be saved by beauty,” Dostoevsky said and to that I add amen. From the first cave drawings and poems etched in clay, it has been so. It is so for me. And sometimes I would rather have a book than bread.

_________________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie’s new novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning will be published in 2014. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

Ancient Amazons as Sailors?

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Classical Numismatics Group

The Amazon strides along, dressed in a tunic and leather boots, carrying her crescent shield and trusty battle-axe. At first glance the image on the ancient coin looks like a typical ancient Amazon, those mythical warrior women modeled on nomadic archers of Scythia, the immense territory stretching from southern Russia to Mongolia. But hold on—what is that object in her right hand? A ship’s anchor! What could be more incongruous? The Amazons were horsewomen galloping over the vast plains, not sailors on the “wine dark seas.”

Historical facts provide some clues to explain the curious image of an Amazon with an anchor. The bronze coin was issued by Ancyra (modern Ankara, Turkey) in the second century AD. Ancyra/Ankara is situated in the arid high plain of Turkey, hundreds of miles from the sea. A Hittite settlement in the Bronze Age, Ancyra was later populated by Phrygians, Mysians, Persians, Greeks, and even Gauls all the way from southern France, before becoming the capital of the Roman Province of Galatia in the first century BC.

Alexander the Great had conquered the city in 333 BC. Soon afterward, Greek merchants and traders settled in Ancyra. These Greeks came from Pontus on the southern coast of the Black Sea (northestern Turkey), an important center of commerce linked to the Mediterranean. The Greeks from Pontus developed Ancyra into great trading hub connecting the Black Sea with the Silk Routes to Asia.

The city’s original Hittite name (Ankuwa) sounded like the Greek word for “anchor,” leading the maritme Greeks from Pontus to make an anchor the town’s emblem, a reminder of their seafaring traditions. The Greek-sounding name demanded a story and several tales were told to explain why the landlocked city was called “Anchor.” For example, some sources traced the name to a dream of King Midas, the mythic founder of Ancyra. The Greeks dedicated anchors in the city’s temples and anchors began to appear on the city’s coins. But why does an Amazon hold the anchor?

The Greek traders who settled Ancyra were originally from Pontus. In Greek mythology, Pontus was the fabled home of the Amazons, who were believed to have made conquests throughout Asia Minor in the deep past. Numerous cities in Pontus and Asia Minor—and even some Aegean islands—claimed that they had been founded by Amazon warrior-queens. It is likely that the Greeks from Pontus who settled in Ancyra took pride in hailing from the legendary homeland of the Amazons. The deck of a ship is last place one would expect to find the archer horsewomen of the steppes and mountains of Eurasia. Yet the coins of Ancyra are not the only evidence for surprising stories of seafaring Amazons. The logistics and geography of several Greek myths about Amazons require that the warrior women must have sailed ships and crossed large bodies of water. We might guess that a lost oral tradition in Ancyra about Amazons and the sea once drew the two symbols together. At any rate, the juxtaposition of an Amazon and an anchor was certainly an eye-catching, memorable image for the trading city’s coinage.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

Ancient Amazon Sailors?

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders and Marvels contributor)

Classical Numismatics Group

The Amazon strides along, dressed in a tunic and leather boots, carrying her crescent shield and trusty battle-axe. At first glance the image on the ancient coin looks like a typical ancient Amazon, those mythical warrior women modeled on nomadic archers of Scythia, the immense territory stretching from southern Russia to Mongolia. But hold on—what is that object in her right hand? A ship’s anchor! What could be more incongruous? The Amazons were horsewomen galloping over the vast plains, not sailors on the “wine dark seas.”

Historical facts provide some clues to explain the curious image of an Amazon with an anchor. The bronze coin was issued by Ancyra (modern Ankara, Turkey) in the second century AD. Ancyra/Ankara is situated in the arid high plain of Turkey, hundreds of miles from the sea. A Hittite settlement in the Bronze Age, Ancyra was later populated by Phrygians, Mysians, Persians, Greeks, and even Gauls all the way from southern France, before becoming the capital of the Roman Province of Galatia in the first century BC.

Alexander the Great had conquered the city in 333 BC. Soon afterward, Greek merchants and traders settled in Ancyra. These Greeks came from Pontus on the southern coast of the Black Sea (northestern Turkey), an important center of commerce linked to the Mediterranean. The Greeks from Pontus developed Ancyra into great trading hub connecting the Black Sea with the Silk Routes to Asia.

The city’s original Hittite name (Ankuwa) sounded like the Greek word for “anchor,” leading the maritme Greeks from Pontus to make an anchor the town’s emblem, a reminder of their seafaring traditions. The Greek-sounding name demanded a story and several tales were told to explain why the landlocked city was called “Anchor.” For example, some sources traced the name to a dream of King Midas, the mythic founder of Ancyra. The Greeks dedicated anchors in the city’s temples and anchors began to appear on the city’s coins. But why does an Amazon hold the anchor?

The Greek traders who settled Ancyra were originally from Pontus. In Greek mythology, Pontus was the fabled home of the Amazons, who were believed to have made conquests throughout Asia Minor in the deep past. Numerous cities in Pontus and Asia Minor—and even some Aegean islands—claimed that they had been founded by Amazon warrior-queens. It is likely that the Greeks from Pontus who settled in Ancyra took pride in hailing from the legendary homeland of the Amazons. The deck of a ship is last place one would expect to find the archer horsewomen of the steppes and mountains of Eurasia. Yet the coins of Ancyra are not the only evidence for surprising stories of seafaring Amazons. The logistics and geography of several Greek myths about Amazons require that the warrior women must have sailed ships and crossed large bodies of water. We might guess that a lost oral tradition in Ancyra about Amazons and the sea once drew the two symbols together. At any rate, the juxtaposition of an Amazon and an anchor was certainly an eye-catching, memorable image for the trading city’s coinage.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 20, 2013

Book News

by Tracy Barrett (W&M Contributor)

I’m thrilled to announce that I’ve joined HarlequinTeen with a deal for two books, the first slated for release in July, 2014, and the second a year or so later.

Random facts I’ve learned about HarlequinTeen:

they don’t publish only romance

they’re a very new imprint of Harlequin

Harlequin is a Canadian company

My new editor, Annie Stone, sent me five of the imprint’s books while negotiations were going on. They arrived just as I was leaving for a vacation—perfect timing! They were all beautifully written, and, since I was reading them with a critical eye, I could tell that they had been beautifully edited.

The first of the two books under contract is called The Stepsister’s Tale, and Annie describes it like this: “a retelling of the classic Cinderella from the stepsister’s perspective, in which beauty, romance, and happily ever after aren’t quite what they seem.”

I already hear you saying, “Another Cinderella story? How could anyone find anything new to say about Cinderella?”

I do think I’ve found a new slant on it, and it’s similar to the slant I’ll take in Book 2, once Annie and I settle on another fairy tale (I think I have it, but it’s taking some pondering). You can judge for yourselves in just over a year whether I’ve truly found something new to say!

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until last spring she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

March 18, 2013

Suleyman the Magnificent Builds a Mosque

by Pamela Toler

Commissioning a mosque was both an act of piety and a political statement in the Ottoman empire. Surrounded by building complexes that provided social services ranging from a public fountain to a caravanserai, mosques anchored new neighborhoods in old cities. Who commissioned what was carefully linked to social status. Small officials commissioned small mosques. Grand viziers commissioned grand mosques. And when the greatest Ottoman emperor and the greatest Ottoman architect teamed up to build a new imperial mosque in Istanbul, you got something, well, magnificent.

In 1550, Suleyman the Magnificent had ruled the Ottoman empire for thirty years. He had defended Islam against Christians to the west and Shiite heretics to the east. He had expanded his empire’s boundaries from Budapest to Basra. He had built mosques everywhere his armies went. Now he was ready to build the big one in Istanbul itself.

Sinan was the acknowledged master of Ottoman architecture. Originally an officer and engineer in the Ottoman army, Sinan had caught the emperor’s eye with his talent for building temporary bridges for an army on the march. Under Suleyman’s patronage, he moved from bridges to buildings when he became Chief Architect of the Ottoman court in 1537. By 1550, Sinan was famous for his treatment of foundations and domes.

Together, Suleyman and Sinan built a mosque that was an Ottoman answer to Hagia Sophia. When the Ottomans conquered Istanbul in 1453, Mehmet the Conqueror physically appropriated the Byzantine cathedral for use as the imperial mosque. Sinan’s act of appropriation was more subtle.

Built 1,000 years before the Suleymaniye Mosque, Hagia Sophia is an architectural masterpiece. Its massive elliptical dome seems to float above the nave of the church because it rests on a ring of windows that separate it from the structure. Glittering mosaics dissolve the interior space of the building into shadowy mystery.

Sinan used the same structural scheme as the Hagia Sophia to create a totally different effect in the Suleymaniye Mosque. In a sixteenth century version of form follows function, the structure that holds the dome in place is clearly visible. Instead of disguising the tension between the curves of the dome and the straight horizontal lines of the building below, Sinan accentuates it. The result? The dome of heaven soars above the human world of prayer.

Photographs courtesy of the Library of Congress and Cornell University.

Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history, a large bump of curiosity, and a red-hot library card. She is the author of The Everything Guide to Socialism and Mankind: The Story of All of Us, a companion book to the History Channel Series of the same name. She blogs at History in the Margins

March 14, 2013

Latin Horse Names

In book XI of Virgil’s Aeneid a horse named Aethon weeps over his fallen master, the young Trojan warrior Pallas. (Aeneid XI 89-90)

The Romans loved their horses and we find their names on inscriptions, epigrams, souvenir beakers and even lead curse tablets. When I was researching my 12th Roman Mystery, The Charioteer of Delphi, I compiled a list.

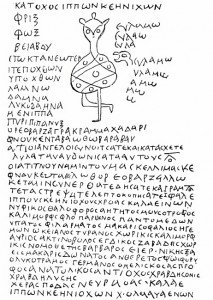

Here are some of my favourite names from the list I compiled. Some of these might possibly to charioteers rather than horses as they were often listed side by side — as on the curse tablet below — but as in English there’s no reason a horse can’t have a “human name”. Or vice versa!

3rd century AD Greek curse tablet with a front view of a horse (or a demon?)

Abigeius (Cattle Rustler)

Achilles [name of a Greek hero]

Adamas (Rock Hard)

Admetus [name of a Greek hero]

Adorandus (Adorable)

Advocatus (Defender)

Aegyptus (Egyptian)

Aethon (Blaze)

Agilis (Nimble)

Agricola (Farmer)

Ajax [name of a Greek hero]

Alcides [= Hercules, a Greek hero]

Altus (Lofty)

Amandus (Darling)

Amicus (Pal)

Amor (Love)

Aquila (Eagle)

Aquilo (North Wind)

Astutus (Cunning)

Aureus (Golden)

Ballista (Missile)

Basilius (Kinglike)

Blandus (Charming)

Bubalus (Gazelle)

Caesarius (Like Caesar)

Calimorfus (Beauty)

Campus (Field)

Candidus (White)

Castor [name of a mythological twin]

Caucasus (from the Caucasus mountains)

Catta (Pussycat)

Celer (Swift)

Cirratus (Curly Locks)

Corinthus (Corinthian)

Cupido (Eager)

Cursor (Runner)

Darius [name of a Persian]

Delicatus (Pretty Boy)

Dignus (Worthy)

Dilectus (Pet)

Diomedes [name of a Greek hero]

Dominator (Boss)

Dromos (Racer)

Elpis (Hope)

Farus (Lighthouse)

Fastidiosus (Choosy)

Felicissimus (Very Lucky) Ferox (Fierce)

Ferox (Fierce)

Frunitus (Jolly)

Gallus (Rooster)

Garrulus (Chatty)

Gemmula (Little Jewel)

Glaucus (Grey)

Halieus (Fisher)

Hiberus (Spaniard)

Hipparchus (Chief)

Hirpinus (from Hirpina, region in Campania)

Icarus [name of the Greek boy who flew and fell]

Inachus [a river in the Argolid]

Incitatus (Bounce)

Indus [name of a river in India]

Ingenuus (Native)

Italus (Italian)

Iuvenis (Laddy)

Lampas (Torch)

Laureatus (Celebrated)

Latro (Robber)

Leo (Lion)

Lucidus (Bright)

Lues (Calamity)

Lupus (Wolf)

Macedo (Macedonian)

Maculosus (Piebald)

Mirandus (Wonderful)

Muccosus (Snotty)

Nauta (Sailor Boy)

Nereus [name of a sea god]

Olympus (from Olympus)

Palmatus (Receiver of the Palm Branch)

Palumbus (Dove)

Parasitus (Toady)

Paratus (Ready)

Pardus (Leopard) Passerinus (Sparrow)

Passerinus (Sparrow)

Patricius (Aristocrat)

Pegasus [name of a mythological flying horse]

Pelops [name of a Greek hero]

Penna (Feather)

Pertinax (Contant)

Phoebus (Bright)

Phosphorus (Morning-star)

Pollux [name of a mythical twin]

Polyneices (Many Victories)

Praeclarus (Renown)

Puerina (Girly)

Pullentianus (Dusky)

Purpureus (Roan)

Pyrobolus (Flame-Thrower)

Regalis (Regal)

Regnator (Emperor)

Roma (Rome)

Romanus (Roman)

Roseus (Bay)

Sagitta (Arrow)

Scholasticus (Studious)

Sica (Blade)

Sidereus (Starry)

Speciosus (Handsome)

Speudosa (Speedy)

Spumosus (Foamy)

Socrates (Greek philosopher)

Sol (Sun)

Tigris (Tiger)

Titas (Titan)

Valens (Powerful)

Verbosus (Chatterbox)

Victor (Winner)

Volens (Willing)

Volucer (Flyer)

London’s Lost Dogs

Between 1700 and 1800, there are almost 500 advertisements for lost dogs in the central London news-sheets. The abduction of cosseted dogs seems to have been a rather lucrative trade, judging by some of the rewards offered. It suits many modern historians to talk of cock-fighting and the riotous Cambridge students who tortured cats, but the nature of many of these advertisements leaves the reader in no doubt of the owners’ affection for their lost companions, whether lap-dogs or working dogs:

Lost on Sunday Night, about Nine of the Clock, from my Lady Gouvernet in St James’s Square, a Dutch Mastiff about 8 Years old, short Legg’d, with a large Neck and Head, pretty fat, big-eyed, short Nose and wide Mouth, his Back black, his belly, Breast, and Neck, Cream colour, with a black circle about his Neck, like a Collar exactly; and when he goes he straddles, and paws with his four Feet. Whoever brings him to my Lady Gouvernet’s House in St James’s Square shall have a Guinea and Reasonable Charges. (Post Boy, February, 1701)

Lost on Saturday last, between Whitehall and Privy Garden, a small Red Dog of the Spaniel Kind, with four white Feet., a White Snip on his Nose, a few white Hairs on the outside of his Neck, and answers to the Name of MUFF. Whoever, brings him to the Right Hon. the Earl of Waldegrave’s, at Whitehall, shall receive Half a Guinea Reward. (Public Advertiser, Novemer 1768)

Lost, a Dog of the Pointer Kind, named Captain, fond of the Water, heavy made, fine Eyes, with an uncommon large Jowl of Flesh under his Throat, entirely white, about six Years old, strayed, or was stolen from Hutchinson’s Stables in Water-Street, near Arundel-Street in the Strand, the first week of last November, (London Intelligencer, 1759)

LOST, on Saturday last, May 5th, near Grosvenor-gate, a yellow and white Spaniel Dog,rather old, very fat, and has lost an eye. Whoever will bring him to Lady Robert Manners, Grosvenor-square, shall have Two Guineas reward. (Daily Advertiser, 1786)

LOST on Tuesday the 3d of July, near the Four Crosses on the Westchester Road, By Woolverhampton, A red and white Bitch, of the Setting Breed, with a red Spot on her Forehead, answers to the Name of Phillis. Whoever brings the said Bitch to Mr. Humphrey Wynne, of Shawberry, near Salop; or to Thomas Wieldup, at the Horse and Groom in Eagle- Street, Red Lion Square, shall receive a Reward of Five Guineas. (London Evening Post, 1753)

DOG. LOST – Strayed from the Door, in Line-street, about 9 o’clock on Sunday morning last, the 17th inst. a very small WHITE BITCH, of the French Breed. She is all over white, excepting a small shade of brown, hardly perceptible, on the rump. Her hair is very curly, stout, four years old, and answers to the name of CLARA. Whoever brings her to Mr Maddocks, No.7 Lime-street will receive TWO GUINEAS for their trouble. (The Times, July 19th, 1796)

Not all notices were for pets. The unfortunate Cripple in this advertisement from the 1746London Daily Advertiser was clearly a guard dog (but not rabid, just mad, probably because of his deformities and possibly cruel treatment):

Whereas a mad Dog has been missing ever since Sunday Night last, from Ivy-Lane, Newgate-Street, which said Dog snarls at the Name of Cripple, and is remarkable for having Wall Eyes, and a great bend in his Back; so this is to forewarn all Passengers passing through Cheapside to take Care they are not bit, knowing he is lurking about the said place.

In July 1800, the Albion and Evening Advertiser carried the extensive case of Atkinson vs. Day, fought over one Caeser, or Charley, depending on which side one believed:

The plaintiff in this action (Atkinson), it appeared, had a bull-dog called Caesar, which was puppied in his premises, which he reared from its infancy, and of which he was very fond. In November last, he lost this dog; he made enquiries after him, and for a long time, without success. In May last, however, one of his servants happened to go into a cook’s-shop about Moorfields, belonging to the defendant, to have a bason of soup; he then conceived that he saw the long lost and much lamented Caesar. He claimed him; the defendant refused to give him up….The defence was, that if Mr Atkinson ever had such a dog as the one in questions, it was impossible that he could ever have had this dog, because it would be proved that this dog, called Charles, was the offspring of the Lover of Smut (best dog name ever? best name ever?), who belonged to a costermonger, otherwise a man who calls apples and vegetables about the street, and of Rose, who was the property of a lamplighter; that Charley was puppied in the premises of Moor, a horse-boiler; that he was one of six puppies, the produce of Rose; that these six were divided among the horse-boiler, the lamplighter, the lamplighter’s wife, Faulkner, the costermonger, a man who drives a cart and another lamplighter called Fisher; that Charley had fallen to the lot of Faulkner, who had brought him up from his infancy, and that he had sold him to Mr Day, the defendant, for one guinea.

This goes on, and on, with both sides calling almost a dozen witnesses to prove their ownership of the dog. A slip on behalf of one of those testifying reveals that he thought Mr Day purchased the dog from Charley ‘the milk-man from over the water’. As it was common for dogs to be named after their owners, the judge deemed that Charley had in fact come from the milk-man, whose round included the Atkinson property. The dog was returned to the Atkinsons, and I’d imagine they bought their milk from someone else after that.

March 11, 2013

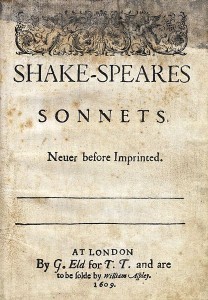

A historical novelist’s search for the secrets behind Shakespeare’s Sonnets

It is fortunate we have these miraculous sonnets at all, as only thirteen copies remain of their original publication in 1609. The writing of them, the subject of them and the unexpected bisexuality of them (incomprehensible to some) remain much disputed more than four hundred years after that date. Here is something about them and how I was able to spend some of the most miraculous moments of my writing career with one of the remaining copies from that printing.

I first bought Shakespeare’s sonnets in a very small blue book at his birthplace in Stratford-on-Avon. For some time I carried it in my pocket or handbag, and read them on the New York City subway going to and from work. At that time I was writing Elizabethan novels and wrote one about Shakespeare called The Players which told a fictional version of the love triangle and another called Nicholas Cooke which also deals with it; they were published by W.W. Norton.

Three major questions remain to us: (1) Who was the so called-dark lady in the sonnets and who was the dazzling young man (2) How did these seemingly private sonnets come to be published and (3) What happened to the rest of the copies?

Yale Elizabethan Club

Popular choices for the Dark Lady (so called because of her dark hair and dusky skin) have been Mary Fitton (a promiscuous lady-in-waiting who evoked the wrath of her mistress Queen Elizabeth) or Emilia Bassano Lanier from the well-known family of Italian musicians popular in the musical Elizabethan court (as claimed by Dr. A.L. Rowse). Dr. Duncan Salkeld claims the Dark Lady may have been a notorious prostitute called ‘Lucy Negro’ or ‘Black Luce’ who ran a brothel in Clerkenwell, London. And Dr Aubrey Burl, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, now believes she can be revealed as Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. Indeed, with a period of six months, two different London newspapers ran articles about the last two scholars with headlines saying the identity of the lady was revealed at last!

There have been many attempts to identify the young man. Shakespeare’s one-time patron, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton is commonly suggested, although Shakespeare’s later patron, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, has also been put forth as a possibility. Now we know that William Herbert became involved with Mary Fitton but if the sonnets were composed between 1592 and 1598, William Herbert would have only been twelve when they were begun!

And then why do only thirteen copies survive? Some people think they were suppressed, that they were published without Shakespeare’s consent and proved embarrassing to poet, dark lady and the fair youth who was a member of the high nobility.

But unfortunately unless some letter hidden away these four hundred years surfaces, we shall not be able to prove the absolute truth. It is an awful pity that most people in those days did not keep letters but often used them to line pie tins (oh the thought of a letter from WS baking away beneath a fragrant kidney pie with bay leaves!). There is hope of course: all sorts of things surface after centuries, found in attics, cupboards, church records, slipped inside other books.

Several years ago, I was able to study one of the thirteen extant copies of the 1609 printing at the Yale Beinecke Library in 1998.

The Earl of Southampton

I boarded the train from New York to New Haven, Connecticut where I was greeted by the curator Stephen Parks. He took me to the white-clapboard “Lizzie” (Elizabethan) Club founded by a Yale alumnus in the early twentieth century as a place for undergraduates and faculty to meet, take tea, study, and discuss art and literature.

Panels hid a vault with two-feet thick walls of concrete; inside were shelved an amazing Elizabethan collection, including the first four Shakespeare Folios, one of the three known copies of the 1604 Hamlet, and the copy of Ben Jonson’s Works (1616) inscribed by the author to his friend and…one of the 13 extant copies of the 1609 edition of the Sonnets.

The little book was rebound in soft green leather tooled with gold and so slender of width that on the binding the tiniest letters had been used to label it: Shakespeare’s sonnets London 1609. And then I was taken to a large reading room where for two miraculous hours, I sat with these poems. The paper of the volume was rough-textured, the printing uneven – now and then, a letter was missing. The shadow of the type on the other side of the page wept through at times. I noted the yellow marks of foxing and a small burn mark on the second sonnet from the spark of fire or candlelight. The printing on the dedication page sloped downward.

The ownership of this copy remained in darkness for 119 years after publication, its first appearance in recorded history being 1728. And as I sat there, I thought, could this copy have belonged to Shakespeare himself? Even if the writer from Stratford was a mere poet and the fair youth nobility, Shakespeare could write in Sonnet 81:

You still shall live, such virtue hath my pen,

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men.

This is the value of great art, though the actual circumstances of its genesis may be waiting for us to discover in some old wood box, behind a wall panel, tucked in a commonplace book in the deserted balcony of a library. Where and when shall it be?

______________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie is finishing a novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

![[Mosque of St. Sophia, Constantinople, Turkey] (LOC)](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1381152705i/4389068.jpg)