Holly Tucker's Blog, page 70

February 18, 2013

Walking Hallowed Ground

By Pamela Toler

Over the years, I’ve walked through many a historical battleground, from the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (just outside the town where I grew up) to the Battle of Hastings. My Own True Love will tell you that I tear up at every battlefield I visit. Or at least get a lump in my throat. (I’m an equal opportunity history nerd.)

But there is no doubt which battlefield hit me the hardest: Gallipoli.

Fought at the Dardanelle Straits, where Turkey has one foot in Europe, the Gallipoli campaign of World War I was the first major amphibious operation in modern warfare. The British and French hoped to drive Turkey out of the war and gain control of the warm water ports of the Black Sea. The campaign started out as a slapdash naval expedition in which the big powers expected to blow Turkey out of the water–so to speak. It turned into the grimmest of trench warfare. Trenches were close enough together that soldiers could toss a live grenade back and forth across the lines several times before it exploded in a horrible parody of the childhood game of Hot Potato. Water was so scarce on the European side that they tanked it in from Egypt. ( That’s a long water run. Look at a map.)

The campaign was a military stalemate paid for by heavy losses on both sides, but it was a formative event for three modern nations: Australia, New Zealand and Turkey. Today ANZAC Day is a national holiday in both Australia and New Zealand, commemorating the landing of Australian and New Zealand forces. The Gallipoli National Historic Park is a pilgrimage site for all three countries.

My Own True Love and I traveled to Gallipoli from Istanbul in a tour bus. Many of our fellow travelers that day were New Zealanders and Australians whose father/uncle/grandfather/great-grandfather had fought at Gallipoli. Our tour guide was a retired Turkish naval captain for whom Gallipoli was a lifelong passion. The museum was heart-breaking. You could walk the trenches in the battlefield. The memorial honored the soldiers from both sides. The combination was magical.

But the thing I remember most clearly is the end of the day. Every tour of the Gallipoli National Historic Park ends in front of a statue of the oldest Turkish survivor of the battle and his young granddaughter, who holds a bouquet of rosemary for remembrance. He is said to have told his granddaughter that every man who died at Gallipoli is part of Turkey now and should be honored. Visitors add rosemary springs to the granddaughter’s bouquet from bushes that surrounded the memorial. Because My Own True Love held the highest military rank of anyone on our bus, Captain Ali invited me to step forward to add a spring of rosemary to the bouquet on behalf of our group. Did I get all teary? You bet.

Remembrance is, ultimately, why we visit battlefields. Remembrance of those who died and those who survived, of causes lost and causes won, of the reasons we go to war, of greed, honor, bravery and shame. Remembrance of the world we have lost on the road to today.

What battlefield visits made an impact on you?

February 15, 2013

Pompeii Myth-Buster

Pompeii buffs beware! If you go on a tour with Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill your world will be rocked as surely as the Pompeians were rocked on several occasions leading up to that fateful day in 79 CE when Vesuvius erupted. Wallace-Hadrill is director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project and author of Herculaneum: Past and Future. Some people call him “Professor Herculaneum”, because few people know Pompeii’s smaller, richer sister-city better.

When Cambridge Alumni Travel in conjunction with Andante Travels offered a once-in-a-lifetime chance to visit ruins on the Bay of Naples with Wallace-Hadrill I jumped at the chance. I had visions of him telling us things no book would reveal and taking us places no tour guide would have access to. I was right. He did get us into places the other tours didn’t reach. But he also demolished some long-accepted facts about the famous eruption of Vesuvius and the ruins it left.

By the end of our first hour with Andrew Wallace-Hadrill I realized he was a Myth Buster extraordinaire. Like all great historians and archaeologists, he does not accept facts just because they’ve been repeated in print a bazillion times. He has a knack for looking at things with fresh eyes and reinterpreting the evidence if necessary.

Here are ten of my most cherished beliefs: BUSTED!

Myth #1 – Vesuvius did not erupt on 24 August AD 79. Everybody confidently quotes this as the date of the eruption, but everybody is probably wrong! At the turn of the 20th century, everybody claimed the eruption occurred in November. But Wallace-Hadrill thinks late September or early October is a likelier date. His clue is a lot of ripe pomegranates found near a buried villa at a place called Oplontis between Pompeii and Herculaneum. (This villa is known as the Villa Poppea or Villa Poppaea because it was owned by Nero’s wife Poppaea.) In Italy, pomegranates ripen in late September/early October. The problem is not with Pliny the Younger, whose famous letters tell us the date of the disaster, but with the monks who interpreted his dates as they copied his manuscripts.

Myth #2 – Villa Poppea not owned by Nero’s Wife. The Villa at Oplontis probably wasn’t called the Villa Poppea and it probably wasn’t owned by Nero’s wife Poppaea. (Though both things might be possible.) Furthermore, the town where it’s located wasn’t called Oplontis. Or maybe it was. We just don’t know.

Myth#3 – population of Herculaneum. Guide books often say the population of Herculaneum was 4,000 people. We simple do not know! Those who hung around were probably vaporized by the first pyroclastic surge. This explains why so few bodies have been found in the town at the foot of Vesuvius. The only bodies we’ve found at Herculaneum were those sheltering deep underground or in the vaulted boat-houses facing the waterfront. But wait…

Myth #4 – not boat-houses. The famous bone-filled “boat-houses” in Herculaneum probably weren’t boat houses. Yes, they were by the sea but they probably had a double function as foundations for the Suburban Baths and storehouses for various goods, (but probably NOT for boats.) Wallace-Hadrill thinks the dozens of skeletons found there were those of people sheltering from what they believed was just another earthquake. He believes there were dozens of earthquakes in the run-up to the eruption, starting with the big one in 62 CE. But wait…

Myth #5 – the earthquake of 62. The famous earthquake of 62 CE was almost certainly in 63 CE. Scholars got the dating wrong. Tacitus tells us who the consuls were and this allows us to date it precisely.

Myth #6 – buried under hot mud! Herculaneum was NOT buried by hot mud as all the guidebooks tell you. It was buried under alternating layers of tufa (hardened ash) and lapilli (light aerated pebbles of volcanic matter). You can see it before your very eyes if you just look.

Myth #6 – don’t call it a thermopolium. The Romans called those fast-food places popinae or tabernae. The word thermopolium only occurs once in Plautus (a 3rd century BC Roman comic playwright). It was probably a joke word. Wallace-Hadrill, the Myth-Buster, called this a “dubious term”.

Myth #7 – don’t call it the Decumanus Maximus. Romans did not call the main road through town the Decumanus Maximus. That is a term invented by modern scholars. They probably called it Venus Street. Or Street of the Fishmarket, or similar.

Myth #8 – don’t call it a lararium. They might have worshipped Hercules or Diana there, rather than the Lares of the household. Call it a shrine, an aediculum in Latin.

Myth#9 – so-called discovery of Pompeii. Pompeii was not really “discovered” in the 18th century. They knew it was there but just weren’t interested or were discouraged by the church from investigating too deeply.

Myth#10 – the erect male member is not always apotropaic. In Pompeii, guides will tell you that phalluses point the way to brothels. Experts tell you the erect member was a symbol of good luck, used against the “evil eye”. But to bust a busted myth: sometimes the phallus DID point the way to a brothel. (see picture at top, of a phallus on a paving stone of the Via dell’Abbondanza, Pompeii’s main drag.)

The main thing I learned from our time with Professor Herculaneum was this: There’s a lot we don’t know. Don’t believe things just because you’ve read them or heard them. Always check the primary sources in conjunction with the archaeological evidence and make up your own mind.

The main thing I learned from our time with Professor Herculaneum was this: There’s a lot we don’t know. Don’t believe things just because you’ve read them or heard them. Always check the primary sources in conjunction with the archaeological evidence and make up your own mind.

For those of you not lucky enough to travel to the Bay of Naples with Andrew Wallace-Hadrill as a tour guide, don’t despair. His lavishly-illustrated and clearly-written book, Herculaneum Past and Future, is now out in paperback. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Caroline Lawrence has written a 17-book series of history-mystery books for children called the Roman Mysteries. Three of the books are set on the Bay of Naples during and after the eruption of Vesuvius: The Secrets of Vesuvius, The Pirates of Pompeii and The Sirens of Surrentum. Find out more at her website: www.carolinelawrence.com

February 14, 2013

Love, Sex and Cuddly Cupids

By Vicki Leon (W&M Guest Author)

By Vicki Leon (W&M Guest Author)

Mid-February in the U.S. brings mushy greeting cards, the overpowering scent of chocolate, and cupids. Lots of cupids.

Call me a cynic, but I don’t buy that old saw that our Valentine celebrations arose from early Christian activists (all named Valentin) whose bloody martyrdom made this a holiday. And them into saints. (There was one female, a Saint Valentina, but her martyrdom was said to have occurred in July of the year 308.)

Having studied the matter for decades while researching the lifestyles, beliefs, and often quirky customs of long-ago Romans and Greeks, I wager that our sometimes sexy, sometimes loving holiday derives from the pagan side of the equation.

For centuries before Christianity came on the scene, the Romans celebrated a mid-February fertility festival called Lupercalia. (It continued to be honored until the 4th century A.D.) This odd ritual involved a cadre of nearly naked male runners, who roamed the city, lightly whipping every nubile female in sight with bloody strips of goathide. Sounds suspiciously like S&M, but it was a purification ritual. The floggings cleansed the city and chased off evil spirits, making Rome’s women receptive in the most basic sense for procreative sex.

The Greeks of old didn’t celebrate Lupercalia. However, they were the first to come up with a love goddess, Aphrodite, who immediately gave her name to aphrodisiacs, among other things. Her son–we’re still unclear about the father–was Eros, from which comes “erotic.” The Romans enthusiastically adopted both of them early on, calling her “Venus” and her son, “Cupid.”

There was a Greco-Roman obsession with deities. They thought nothing of adding to the already-massive roll-call of gods and goddesses. Thus, at one point, they decided that the love goddess and her sidekick needed help. In nine out of ten myths, she had little maternal control over her son Eros/Cupid, who as everyone knew, was in charge of sexual passion, the juvenile delinquent of the family. (Frightening, the way that kid armed himself with state-of-the-art weaponry.)

Given her deplorable parenting skills, Venus could not keep up with the demands on her time. All those anguished parents, star-crossed lovers, horny teens, forlorn widows, and brides forsaken at the altar needed more divine help. They looked to her for solace. For answers, darn it.

What was the ingenious solution that Greeks (and the copycat Romans) came up with? They took a long hard look at love, lust, and longings, then subdivided those emotions into categories. Once identified, they created a lineup of subordinate demi-gods to handle those calls, so to speak. The concept resembled our smartPhones and answering machines, with their “Press 1, Press 2,” menu choices.

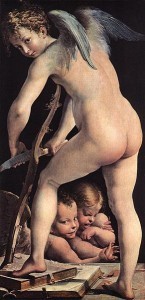

The minor deities that the folks of long ago dreamed up were cuddlesome little rascals. Like Eros/Cupid, they were depicted as young boys or even toddlers. They had rosy, infantile bodies with wings. They ran about nude, playfully shooting arrows and getting into adorable mischief. As a group, they were called the Erotes–the little loves. In art, they often served as the entourage to Eros/Cupid.

Since the Greeks recognized both unrequited love and requited love, they created Himeros and Anteros to report to for people with those afflictions. Or blessings. Popular among the morbidly depressed, love-gone-wrong population was a godlet named Pothos, who commiserated over sexual yearnings. For lovers new to the game, a pair of Erotes called Peitho and Hedylogos handled issues like seduction, sweet-talk, pickup lines, and similar matters.

Taken as a whole, the Erotes provided emotional help and an on-call support group to the general populace.

In addition, the Erotes caused legions of painters, sculptors, and muralists all over ancient Italy, Greece, and the rest of the Roman Empire to breathe a huge sigh of relief. At last! Some fresh new material to work with, a variety of cuddly, fleshy cupids to brighten otherwise humdrum murals, friezes, wine goblets, chamberpots, and more.

Vicki Leon, nonfiction author of 37 books, includes this tale and 88 others in her newest book, The Joy of Sexus. (Walker, January 2013).

February 13, 2013

Valentine’s Day according to The Star, 1791

Happy Valentine’s Day! The following are the Valentine’s Day entries from London’s Star newspaper on February 14th, 1791.

VALENTINE

———-

Arise, arise, sweet VALENTINE,

To see the Sun in lustre shine;

As liveried clouds around him wait.

Arrang’d in more than usual state;

Propitious on thy natal day,

While surly Winter slinks away

With all his ruffian blasts amain,

Disturber of thy gentle reign.

Welcome Spring in mantle green

Whose emblem’s in my ANNA seen.

In whom lives all that nature taught,

Or fancy’s self from genius caught;

For truth must hail thee all divine,

My love, my hope, my VALENTINE.

J.F.

———————————————————————————————————————–

There is a rural tradition on this day, birds chuse their mates; from when probably arose the custom of chusing Valentines, which affords an innocent exercise for the fancies of young people in various parts of Europe….Ghosts were anciently supposed to have the power of walking on the night of this day, when it became the custom in the followers of the Romish superstition to chuse on this day their Protecting Saints. On this day, in the North of England, and in Scotland, it is usual for young persons of both sexes to interchange presents. (Thomas) Pennant says, in his Tour of Scotland, that the drawing of Valentines is done there with great seriousness, as involving the future fortune of the married state. See also Dr. Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield, where, in a description of rustic manners, we are told it was always customary to send true love knots of Valentine morning. Valentine, whose name has been given o this day, was a primitive father of the Church, beheaded in the reign of the Emperor Claudius.

(John) Gay has given us a pretty description of rural ceremonies observed on this day:

Last Valentine, the day when birds of kind

Their paramours with mutual chirpings find,

I early rose, just at the break of day,

Before the Sun had chased the Stars away;

A-field I went amid the morning dew,

To milk my kine, for so house-wives do;

The first I spied, and the first swain we see,

In spite of fortune shall our truelove be.

February 10, 2013

A Short History of Valentine’s Day

By Mary Sharratt

The origins of Saint Valentine’s Day lie shrouded in obscurity. Saint Valentine himself, a third century Roman martyr, seems to have nothing to do with the romantic traditions that became associated with his feast.

Dr. Douce, in his Illustrations of Shakespeare, cited in The Book of Days, writes:

It was the practice in ancient Rome, during a great part of the month of February, to celebrate the Lupercalia, which were feasts in honour of Pan and Juno. whence the latter deity was named Februata, Februalis, and Februlla. On this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian church, who, by every possible means, endeavoured to eradicate the vestiges of pagan superstitions, and chiefly by some commutations of their forms, substituted, in the present instance, the names of particular saints instead of those of the women: and as the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, they appear to have chosen St. Valentine’s Day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.

The first mention of Valentine’s Day traditions in England originate from the 14th century writers Geoffrey Chaucer and John Gower who both allude to the folk belief that birds choose their mates on the feast of Saint Valentine, their patron.

In Britain, the mating flights of crows, rooks, and ravens can generally be observed by February 14. Here in Lancashire, I notice more and more birdsong each day as February advances and the birds repair their nests, preparing for a new cycle of birth and life.

Around 1440, John Lydgate’s poem in honour of Queen Katherine, widow of Henry V, is the first to mention romantic traditions among humans associated with this date:

To look and search Cupid’s calendar,

And choose their choice, the great affection.

People of both sexes sent tokens of admiration. You could either send a token to the romantic interest of your choice, or draw lots as to who would receive your Valentine. In 1470s Norfolk, the Paston family seems to have preferred drawing lots rather than sending tokens to a chosen person.

Actual Valentines could be quite costly. In 1523, Sir Henry Willoughby, gentleman of Warwickshire, paid 2S, 3d for his. Unfortunately no description of this costly item remains for us today.

After the Reformation, the feast of Saint Valentine was abolished, and yet the amorous traditions flourished.

By 1641, the system of casting lots for Valentines was so well known in Edinburgh that a wag waggishly proposed their new Lord Chancellor be chosen by the same method.

A Dutch visitor to London in 1663 observed:

it is customary, alike for married and unmarried people, that the first person one meets in the morning, that is, if one if a man, the first woman or girl, becomes one’s Valentine. He asks her name which he takes down and carries on a long strip of paper in his hat band, and in the same way the woman or girl wears his name on her bodice; but it is the practice that they meet on the evening before and choose each other for their Valentine, and, come Easter, they send each other gloves, silk stockings, or sometimes a miniature portrait, which the ladies wear to foster the friendship.

In his diaries of the same decade, Samuel Pepys reveals how he would call by a colleague’s house early in the day in order to make the man’s daughter his Valentine. Pepys would also arrange for a young man to call to pay the same homage to Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents, which Pepys then paid for. One year when Pepys was short of cash, alas, no young man with presents appeared and Mrs. Pepys was quite irate. Eventually they settled on a yearly ritual, whereby Pepys’s cousin paid a visit to honour Mrs. Pepys and bring her presents which Pepys knew she desired.

Sources:

The Book of Days

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

February 9, 2013

The history of menstruation

Julia Margaret Cameron’s Hypatia

By Helen King (W&M Regular Contributor)

Everything has a history. I suppose it was only a matter of time before I wrote about menstruation here; my doctoral thesis was on menstruation in classical Greece. One of the questions I couldn’t answer there was ‘What did women actually do about the bleeding?’ Did women in the past lose less blood, so that just bleeding on to their clothes was an option? Or did they use pads, and if so how did they make them and how were they attached – to the body or to the clothes?

In 2008 Sara Read wrote a fascinating article about early modern women’s menstrual practices. In it she referred to a version of the story told about the late antique philosopher Hypatia. Hypatia threw her menstrual cloths – in Jacques Ferrand’s early seventeenth-century version, which Sara used, the Latin is pannus menstruus – at an unwanted suitor, presumably to put him off his idealised image of her by confronting him with the realities of the female body. Following up eighteenth-century readings of this story, I found that some men regarded Hypatia as a model of virtue; unable to face up to the original sources, they transformed the item she threw into ‘a handkerchief, of which she had been making some use on that occasion’ (The Female Worthies, 1766). Others, seeing her as ‘an impudent school-mistress’, told the story but left this particular incident in the decent obscurity of the original Greek (The History of Hypatia, 1721).

A similar cloth turns up in a passage of ‘On Treatments for Women’; part of what Monica Green called the ‘Trotula ensemble’ of medieval texts. Here, women with ‘bloody flux at the same time as the menses’ are told to sit on wild rocket cooked in wine, with a linen cloth (pannus lineus) put between them and the rocket. Although this is a remedy, not what is done for normal menstruation, it may suggest normal practice too.

The Latin pannus menstruus translates a Greek term, ‘the rhakoi of women’. Rhakoi are ‘rags’, as in the modern phrase ‘on the rag’. The great German historian of ancient Greece, Theodore Mommsen, once got very over-excited about the inventory of gifts left for the goddess Artemis at one of her sanctuaries. He spotted the word rhakos and decided that girls used to dedicate their menstrual rags to Artemis. He then got into a terrible state trying to work out where these would have been stored in the sanctuary. More recent scholars have pointed out that we don’t need to go this far. The word simply means ‘ragged’, and indicates that those making the inventory were observing that some of the clothing dedicated by women to the goddess was looking a bit threadbare.

Sara pointed out that one of the reasons why we don’t really know for certain what women did is that they didn’t talk about it either. It’s men who tell us the few things we know, and we don’t know whether women’s attitude was the same or not. We don’t even know what level of blood loss they expected – apparently this can vary with diet, and people were not as well-fed in the past as we are now – but the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises assume a ‘wombful’ of blood every month, with any less of a flow opening up the risk of being seen as ‘ill’ and hence leading to remedies like the dreaded beetle pessaries. Maybe I’ll come to them on another occasion!

Further reading:

Sara Read, “‘Thy righteousness is but a menstrual clout’: sanitary practices and prejudice in early modern England,” Early Modern Women 3 (2008), 1-25 (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jsp...)

and check out the Museum of Menstruation, http://www.mum.org/

February 8, 2013

The Man Who Played Hitler

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

As a schoolboy, Bobby Watson sold peanuts amid the laughs and groans in the Olympic Theater in Springfield, Illinois. He soon became a vaudevillian himself, joined a traveling medicine show, and struggled to the stages of Broadway by the time he was 30. There Watson made his mark as a musical performer and comedian, performing in such shows as The Rise of Rosie O’Reilly, American Born, and The Greenwich Village Follies.

Bobby Watson as Adolf Hitler in the 1943 movie Natzy Nuisance. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Who could have guessed that the prat-falling and facially expressive actor would someday become best known for his repeated portrayals of the world’s most reviled leader, Adolf Hitler?

Germany’s führer had first become actor’s fodder in 1935, when the actor Konparu Minamizato played him in the little-seen Japanese short film Uma Kaeru. Five years later, in his most commercially successful film The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin appeared as Hitler and famously performed a mock ballet with a floating globe.

At about the same time, however, someone noticed that Watson — already of veteran of dozens of minor film comedies — bore a strong resemblance to Hitler. When he donned a National Socialist costume, brushed across his hair, and sported the distinctive Hitlerian mustache, the similarity was remarkable. Watson appeared as the Nazi for the first time in a Three Stooges short titled You Natzy Spy, which was followed by another Moe, Larry, and Curly comedy called I’ll Never Heil Again.

From those roles as Hitler, Watson was off and running. He impersonated Hitler many times in the years that followed, in such films as Hitler: Dead or Alive (1942), The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), The Hitler Gang (1944), A Foreign Affair (1948), The Story of Mankind (1957), On the Double (1961), and finally The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962). Only Watson’s death in 1965 ended the streak.

Watson, it should also be remembered, acted in many movies without wearing the swastika armband. He was an Ozmite in The Wizard of Oz and a diction coach in Singin’ in the Rain, and he wrote three comedies that were produced during the 1930s.

After Watson, many more actors chewed through parts as the German leader. Among the best known are Billy Frick (who only appeared in films once not as Hitler), Anthony Hopkins, Alec Guinness, Michael Sheard, Ian McKellen, and Derek Jacobi. None of these great actors looked the part more than Watson. For the rest of human history, Hitler’s image in newsreels and Leni Riefenstahl documentaries will compete against the comic portrayals of the boy from Springfield.

Sources:

Bakke, Dave. “Famous Springfieldians.” Springfield State Journal-Register, November 6, 2011.

Mitchell, Charles P. The Hitler Filmography: Worldwide Feature Film and Television Miniseries Portrayals, 1940 through 2000. McFarland, 2002.

February 7, 2013

Research Hell, um, I mean Research Query

By Holly Tucker (W&M Editor)

Hi everyone…we interrupt our regular programming for an urgent call for help.

I’m in the thick of writing and research for my next book, which is under contract with W.W. Norton. I’m not allowed to say much about it right now…other than that I may genuinely be more excited about this one than I was for my last one (Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution).

So here’s the challenge:

The current book requires me to consult thousands upon thousands of pages of court records and interrogation reports. Many of these reports exist only in manuscript scribble–which brings its own special form of suffering, err, delight. But for the moment, I’m focusing on about 5 hefty volumes of transcribed texts.

The documents in are in PDF format and–another wrinkle–all in French. They contain testimonies from hundreds of people, who were each ostensibly up to some fabulously wicked things, OR who were being accused of similarly fabulously wicked things.

To make sense of the avalanche of accounts, I need to put together an index or concordance of each witness and each person who is named in the accounts. This is critical for me to be able to figure out who was up to what, when, and why.

Really, I just want something simple like this.

Curie, Marie. 5, 29, 523, 1502. (ideally with the page numbers hot-linked to location in the PDF itself)

Curie, Pierre. 16, 99, 504, 1412.

I could create a hand-coded index, a process that would take me well into my twilight years. Or I could extract each letter/report/record contained in the PDF and import each into my database (Devonthink Pro Office) and tap the “see also” AI functions of DTPO. But, call me crazy, I’d like to finish this book at some point in the foreseeable future. (And so would my editor…who is expecting the manuscript in the next 15 months. Gulp.)

I’ve looked at book indexing programs like Cindex ($500+!), PDF Index Generator (which could work, if the computerized voice on the tutorials didn’t bug me so much), as well as many articles on indexing strategies (see, for example, this ProfHacker article).

Adobe Acrobat Pro will let me save individual searches into nifty files. But it doesn’t seem to be able to organize multiple searches into a single hot-linked document. So I could end up with hundreds of different files for the hundreds of different people/historical figures I’m trying to track right now. (Cue sound of head pounding on wall.)

For those of you who know me, I usually get excited about finding just the right tool for just the right research need. For the record, the programs I could not live without are: Dropbox, Devonthink Pro Office (database), Scrivener (writing program), Sente (citation manager), and Aeon Timeline, which has been amazing as I plot chronology for the book.

Alas, as much as I wish that I were a true Research Sensei, I admit only to being a clueless dolt. This indexing question is truly kicking me in the pants.

So help this poor soul? Share Tips? Strategies? (NB: No deep programming skills required, please. The whole point is to simplify the process, rather than complicate it with a steep learning curve.)

And if all else fails, offers to buy me a drink and join me in commiseration?

February 6, 2013

Alexander the Great and the Rain of Burning Sand

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonder & Marvels contributor)

In 332 BC Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army suffered the effects of a fiendish chemical incendiary that caused horrendous casualties. During Alexander’s seven-month siege of the Phoenician city of Tyre (now Lebanon), the Phoenicians realized that they needed a powerful antipersonnel weapon to “conquer such a courageous enemy.” They devised “an ingenious and horrible torment which even the bravest could not deflect.” The ancient Greek historian Diodorus described the battle.

The Phoenicians heated fine sand in enormous shallow bronze bowls. Then they either poured or catapulted the red-hot sand over Alexander’s soldiers. The sand rained down on “those who were fighting most boldly, bringing them utter misery.” There was no escape for anyone within range, says Diodorus, as the molten grains of sand “sifted down” on the Macedonians, “searing their skin with intense heat, inflicting terrible pain.” Diodorus tells how the victims writhed, trying to shake off the sand, “shrieking like those under torture.” In “excruciating agony,” Diodorus continued, many of Alexander’s men “went mad and died.”

The account of the rain of burning sand at Tyre, created two millennia ago, bears an uncanny resemblance to the effects of a modern chemical incendiary, white phosphorus. Like the burning grains of sand deployed by the Phoenicians, the hot metallic embers of white phosphorus cause clothing and other materials to combust. When white phosphorus bombshells burst, the explosion showers white-hot shrapnel that sticks to the skin and burns through flesh to the bone, causing severe deep burns or death. Wounds continue to smolder even after dressings are applied. Much like the Phoenicians’ heated sand, the tiny intensely hot flakes of phosphorus continue to burn as they penetrate deeply through skin and flesh, causing severe burns or death.

White phosphorus clearly has all of the horrific features of a chemical weapon. It is widely dispersed with no means of precise delivery to targets, inevitably blanketing civilians within range, causing extreme suffering to anyone it touches. Currently, white phosphorus is not classified or banned as a chemical weapon. It seems that history’s lessons should be enough to convince us that no government can justify deploying chemical armaments or any substance that behaves like one. Yet numerous reports allege that white phosphorus antipersonnel weapons have been used in the past few decades in the Middle East and Central Asia (Iraq, Libya, Yemen, Chechen, Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Gaza). Such claims are usually denied, with rationalizations that the phosphorus is used only for nighttime illumination or to create dense smoke cover for advancing troops.

Chemical weapons are generally assumed to be modern inventions, but their roots are very ancient. It is sadly ironic that an ancient precursor to phosphorus incendiaries was reported more than two millennia ago in this same historically war-torn corner of the world.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

February 4, 2013

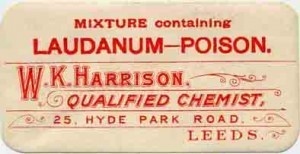

Poetry, pain, and opium in Victorian England: Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s use of laudanum

Elizabeth Barrett began to take laudanum, a tincture of opium, for what is thought to have been a spinal injury at the age of fifteen. It is believed she continued to take it through two more serious illnesses in her early 30s (hemorrhaging of the lungs and some extended unspecified illness). It was almost impossible for her to stop it once she had begun it and it worked for and against her.

Laudanum is an alcoholic herbal preparation which contains about 10% opium; it is very bitter. It was used for many purposes, principally a pain reliever and cough suppressant. She took it for emotional and physical reasons: to slow her rushing heart and to help her sleep, to suppress the cough which could bring on bleeding. It became for her a general panacea. The drug was also used against menstrual cramps.

Laudanum was entirely uncontrolled in the Victorian era; few people took its side effects seriously. Bouts of euphoria were followed by bouts of depression, slurred speech, restlessness, poor concentration while withdrawal could produce muscular aches and abdominal cramps, agitation, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. But even infants were spoon fed laudanum and it was not until years after that people realized it was addictive.

An anonymous report, published in The Journal of Mental Sciences January 1889 and called “Confessions of a Young Lady Laudanum-Drinker,” is rather horrifying. The woman wrote, “Laudanum got me into such a state of indifference that I no longer took the least interest in anything, and did nothing all day but loll on the sofa reading novels, falling asleep every now and then, and drinking tea. My married sisters… said I always seemed to be in a half-dazed state, and not to know what I was doing….my memory was getting dreadful.“ After a time, the young woman quit cold, a great difficulty. “My principal feeling was one of awful weariness and numbness at the end of my back; it kept me tossing about all day and night long. It was impossible to lie in one position for more than a minute, and of course sleep was out of the question. Does anyone who has gone up to three or four ounces a day, and is suddenly deprived of it, live to tell the tale! “

When the poet Robert Browning visited Elizabeth, who was by then much weakened by laudanum and lack of exercise (her family kept her in her room or in the house from fear of what the wretched London fog would do to her lungs), he probably did not understand the extent of the laudanum use. Browning knew she needed to escape from her autocratic father who would not let any of his grown children marry and thus he swept her away to live in Italy. There she regained remarkably good health, though she continued to miscarry her children until Robert and her maid Wilson convinced her to reduce her laudanum dose. Then she bore a healthy child.

When the poet Robert Browning visited Elizabeth, who was by then much weakened by laudanum and lack of exercise (her family kept her in her room or in the house from fear of what the wretched London fog would do to her lungs), he probably did not understand the extent of the laudanum use. Browning knew she needed to escape from her autocratic father who would not let any of his grown children marry and thus he swept her away to live in Italy. There she regained remarkably good health, though she continued to miscarry her children until Robert and her maid Wilson convinced her to reduce her laudanum dose. Then she bore a healthy child.

But for those patients who took laudanum so regularly in the Victorian era, we must consider that there were few other pain relievers until aspirin in 1899. If Mrs. Browning had had antibiotics, she might have cured her lung infection. A mild tranquillizer would have calmed the agitation she felt living with her father (I suspect she had tachycardia). A bit of Ambien or Tylenol PM would have let her sleep. She would not have been so weak.

My research into Elizabeth Barrett Browning is fraught with unanswered questions as must be the research into the health and remedies of most historic people in the Victorian era or earlier. I have read her dosage was at least four times that of the average dosage of opium today. If so, how did she write so much poetry, so many letters? Did it help or harm her? It seems she had pretty good health in the five years after she went to Italy. She could climb steep hills, walk for hours, endure days of jolting carriage rides. When her maid went on holiday, she cared for her toddler. Her health declined around the fifth or sixth year of marriage. Final photographs of her show a very sick woman. Sometimes she could not walk from bed to chair. Did laudanum help her? Or did it hasten her death?

Other laudanum users of the 19th century include Byron, Shelley, Keats, Dickens, Poe, Coleridge, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, the British model, poet, and artist, died of an overdose.

______________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Stephanie is finishing a novel on the love story of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com