Holly Tucker's Blog, page 73

December 13, 2012

12 Days of Books: Big Bang, Big Brains, Big History

By Pamela Toler (Wonders and Marvels Contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

* * *

Mankind: The Story of All of Us is the history of the world from the Big Bang to the 21st century—told in six two-hour television episodes and one 437-page book.

Writing the companion book for a television series is different than writing a book based on your own concept. You have to work within the constraints of other people’s visions of what the book should be. You have to match the style and structure of their vision while still creating something that stands on its own and is recognizably yours. You have to leave stuff out that you really, really want to include. (Alas, the Indus Valley civilization did not make the cut.)

I will admit that I was slow to catch on. “Think the Bourne Ultimatum” made me want to bang my head on the table. “Think Man as the hero of his own story” made me grind my feminist teeth. But “Think Big History” caught my attention. This was a concept I could work with.

Big History integrates many academic disciplines in order to look at human history as a tiny part of the history of cosmos. Basically, it’s the opposite of the academic mantra “not my field”. This TED talk by Big History promoter David Christian sums up the general principles:

http://www.ted.com/talks/david_christian_big_history.html

In a true Big History book, homo sapiens would appear in the last chapter. Maybe even on the last page. Obviously that wouldn’t work in a book called Mankind. But the principles of Big History did encourage me to ask different questions. Not just how the salt trade functioned in ancient times, but why our bodies need salt. Not just when did farming start, but how was grain domesticated. Not just the role of fire in making tools, but the role of fire in making modern man.

Ultimately Big History helped me write big history.

Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history, a large bump of curiosity, and a red-hot library card. She is the author of The Everything Guide to Socialism and Mankind: The Story of All of Us, a companion book to the History Channel Series of the same name.

Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history, a large bump of curiosity, and a red-hot library card. She is the author of The Everything Guide to Socialism and Mankind: The Story of All of Us, a companion book to the History Channel Series of the same name.

December 11, 2012

12 Days: Christmas… a Roman Holiday?

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

by Caroline Lawrence (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

When I was researching my sixth Roman Mystery, set during the mid-winter festival called the Saturnalia, I was amazed by how many ancient Roman customs have survived, embedded in our Christmas celebrations. Here are twelve!

When I was researching my sixth Roman Mystery, set during the mid-winter festival called the Saturnalia, I was amazed by how many ancient Roman customs have survived, embedded in our Christmas celebrations. Here are twelve!

1. Five day vacation. In the first century AD the Romans set aside five days holiday to celebrate the festival of the Saturnalia, a mid-winter pagan festival to bring back the sun. We take approximately the same number of days off for Christmas.

2. December 25th. Romans sacrificed to Saturn but by the first century some were celebrating the birth of an eastern god of light on the 25th of December. No, not Jesus: Mithras! His rites and rituals shared many similarities with our Christian ceremonies. There was a baptism, a sacramental meal, an observance of Sunday, and the god himself was born on the 25th of December

3. Christmas tree, mistletoe, wreaths, etc. Romans decorated their houses with greenery. As Sheldon from Big Bang Theory says, “In the pre-Christian era, as the winter solstice approached and the plants died, pagans brought evergreen boughs into their homes as an act of sympathetic magic, intended to guard the life essences of the plants until spring. This custom was later appropriated by Northern Europeans and eventually became the so-called Christmas tree.”

4. Lights & candles. Romans also decorated their houses with extra lights at this darkest time of the year. Again, this was a pagan attempt to bring back the sun. Torches, tapers, candleabra and oil-lamps flickered throughout the houses of the rich. Because of this Rome was a particular fire hazard in the winter. One historian estimates that a hundred fires broke out daily in the Eternal City, which had its own entire corps of firemen, the vigiles.

5. Feasting! In mid-winter instinct tells us to build up a nice layer of fat, to feast in preparation for lean times ahead. A bit like a bear before hibernation. Yum. Carbohydrates are on the menu again.

6. Drinking. It has been medically proven that a small amount of wine added to water will kill off most known bacteria. For most of the year Romans drank diluted wine, but during the Saturnalia they often drank neat wine, heated and spiced. That’s my excuse for a glass of mulled wine: it’s hygienic.

7. Partying & Role Reversal. For the five days of the Saturnalia, slaves didn’t have to work. They could eat, drink and be merry. Some masters let their slave switch roles. Others, like Pliny the Younger, just left them alone to get on with it. Today, office employees find Christmas the time when they are tempted to take the most liberty. Be careful. Once the Saturnalia is over, you have to go back to being a slave… er, employee.

8. Board games and/or cards. In first century Rome, the only time gambling was legally permitted was during the Saturnalia. Even children and slaves could roll dice for nuts or money without fear of punishment. In the West, Christmas is the only time many families play board games or cards.

9. Party pieces. On the first night of the Saturnalia many households threw dice to determine who would be the King of the Saturnalia. The “King” could command people to do things like prepare a banquet, sing a song, or run an errand. Today we often perform party pieces at our Christmas parties, but Mom usually gets landed with preparing the banquet.

10. Santa hats. Many Roman citizens wore the hats traditionally given to slaves when they were set free. The pileus or pileum – both forms are attested – showed that freeborn Roman citizens were “extra free” from the usual restrictions and laws. These “freedom caps” were conical in shape and made of colourful felt, perhaps fur-trimmed in the winter. Hmmm. A red felt conical hat trimmed with white fur. Remind you of anything?

11. Presents! The Romans gave gifts on the Saturnalia, especially small clay or wooden figures – sigillum singular, sigilla plural – often with moveable joints. Action figures, LEGO and Barbies are our modern equivalent!

12. Gift tags. Finally, Romans often composed two-line epigrams to accompany their Saturnalia gift. So come on all you NaNoWriMo graduates and would-be writers: try composing your gift tags as a two line poem!

What better book to giveaway for our 12 Days of Books Giveaway than The Twelve Tasks of Flavia Gemina. To win a copy signed by me, just comment on this post in Latin or English, poetry or prose.

Caroline Lawrence has been writing detective stories about first century Rome and the Wild West for over a dozen years. Her passion for plotting combined with an obession with historical accuracy means her history-mystery stories are popular with children, parents and teachers. Here she is at a Christmas booksigning, wearing her pileum or freedom cap. www.carolinelawrence.com

12 Days: On the Trail of a Lobotomist

by Jack El-Hai (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

Like many of my literary quests, my book The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness began by chance and took a long time to complete.  Back in 1996 I was the author of a single book about the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, devoid of ideas for any new books I could write, when I found an interesting letter to the editor in the morning newspaper. The writer declared her support for efforts then going on to replace anonymous grave markers at state psychiatric hospitals with named markers. Most interestingly to me, she went on to briefly mention that her deceased uncle had been a hospital patient who received a lobotomy as a ward of the state in 1968.

Back in 1996 I was the author of a single book about the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, devoid of ideas for any new books I could write, when I found an interesting letter to the editor in the morning newspaper. The writer declared her support for efforts then going on to replace anonymous grave markers at state psychiatric hospitals with named markers. Most interestingly to me, she went on to briefly mention that her deceased uncle had been a hospital patient who received a lobotomy as a ward of the state in 1968.

I remember rereading that sentence several times. I did not know that patients had undergone lobotomies so close to where I lived, and as recently as the late-1960s. All I knew about this treatment, in fact, had come from a disturbing scene in the movie Frances, about the mentally troubled actress Frances Farmer (a film I later learned was fictionalized). I tore out the letter-writer’s message, tacked it onto my bulletin board, and spent three weeks trying to ignore it before giving her a call.

She welcomed my call and connected me with her other uncle, a brother of the lobotomy patient. Together they spent hours telling me their relative’s moving and complex story before and after his lobotomy. It seemed as if they had been waiting for someone to show interest and ask for details.

This one patient’s tale inspired me to propose and write an article about the use of psychiatric surgery in the Upper Midwest, for the magazine of the Minnesota Medical Association. Researching that article exposed me to the work of neurologist Walter J. Freeman, the treatment’s developer and advocate. A Minnesota neurosurgeon had given me a vivid picture of what it was like to witness one of Freeman’s gruesome transorbital (sometimes called “ice pick”) lobotomies in a state hospital demonstration. So I next wrote an article about Freeman’s career for The Washington Post Magazine, which I followed with a book proposal. I sold The Lobotomist to a publisher and spent a year and a half in writing it. By the time of the book’s publication, nine years had passed since I had picked up the phone to call the patient’s niece.

I now embrace book ideas that plummet out of the blue. While working on The Lobotomist, I learned that Walter Freeman made a macabre hobby of studying psychiatrists who had committed suicide. In an obscure book he briefly recounted the career of Douglas M. Kelley, a U.S. Army psychiatrist who examined the top Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg and took his own life twelve years later. Kelley’s life and close connection with such notorious figures as Hermann Goering and Rudolf Hess intrigued me, and my book about his crooked path, The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, will be published next year.

Comment on this post to win a free copy of The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness.

Jack El-Hai has contributed articles on history, medicine, and science to The Atlantic, Wired, The History Channel Magazine, and many other publications.  His book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist was recently optioned for screen and stage by Mythology Entertainment, which is currently developing a series based on The Lobotomist for HBO.

His book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist was recently optioned for screen and stage by Mythology Entertainment, which is currently developing a series based on The Lobotomist for HBO.

12 Days: The Greatest Voice of Her Age

By Mary Sharratt (W&M Contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

Born in the Rhineland in present day Germany, Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath, a Renaissance women before the Renaissance. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12th-century woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine.

Born in the Rhineland in present day Germany, Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath, a Renaissance women before the Renaissance. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12th-century woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine.

2012 was Hildegard’s year. In May she was finally canonized, over eight centuries after her death, and in October she was elevated to Doctor of the Church, only the fourth woman in history to receive this rare distinction.

For twelve years I lived in Germanywhere Hildegard has long been enshrined as a cultural icon, admired by both secular and spiritual people. As a writer, I was struck by the pathos of her story. The youngest of ten children, Hildegard was offered to the Church at the age of eight. She reported having luminous visions since earliest childhood, so perhaps her parents didn’t know what else to do with her.

According to Guibert of Gembloux’s Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was bricked into an anchorage with her mentor, the fourteen-year-old Jutta von Sponheim, and possibly one other young girl. Guibert describes the anchorage in the bleakest terms, using words like “mausoleum” and “prison,” and writes how these girls died to the world to be buried with Christ. The anchorage was situated in Disibodenberg, a community of monks. What must it have been like to be among a tiny minority of young girls surrounded by adult men?

Hildegard spent thirty years interred in her prison, her release only coming with Jutta’s death. At the age of forty-two, she underwent a dramatic transformation, from a life of silence and submission to answering the divine call to speak and write about her visions she had kept secret all those years.

In the 12th century, it was a radical thing for a nun to set quill to paper and write about weighty theological matters. Her abbot panicked and had her examined for heresy. Yet miraculously this “poor weak figure of a woman,” as Hildegard called herself, triumphed against all odds to become the greatest voice of her age.

Hildegard’s life was so long and eventful, so filled with drama and conflict, tragedy and ecstasy, that it proved mightily difficult to squeeze into a manageable novel. I also felt quite intimidated to write about such a religious woman. In the end, I found I had to let Hildegard breathe and reveal herself as human.

Comment on this post to win a free copy of Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen

Mary Sharratt’s newest title, Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, is published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and is a Kirkus Best Fiction of 2012 selection. Mary’s articles and essays have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Huffington Post, Publisher’s Weekly, and on NPR.

December 10, 2012

12 Days of Books: Twelve

by Tracy Barrett (W&M contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

Twelve days of Christmas. Twelve months in a year. Twelve inches in a foot. Twelve hours on a clock and 12 x 2 hours in a day. Twelve apostles. Twelve gates to the city. Twelve animals in the Chinese horoscope. Twelve Sanskrit names of God. Twelve disciples of Mohammed and Mithra. Twelve signs of the zodiac. Twelve tribes of Israel.

What is it with the number twelve?

It has such a powerful hold on our collective imagination that the normally meticulous and scarily accurate copy editor of my most recent novel, Dark of the Moon, “corrected” me when I mentioned the thirteen moon-cycles in a year (there are 28 days in a cycle; 13 x 28 = 364). She just couldn’t wrap her mind around the fact that although there are twelve months in a year, there are thirteen moon-cycles.

Thirteen is similarly unlucky in many cultures, to the point where there’s a word for fear of the number thirteen: triskaidekaphobia. Examples of the evil and frightening nature of thirteen are way too numerous to list.

Some would have it that our leeriness of the number thirteen comes from the number of diners at the Last Supper, but it’s much older than that. In fact, it’s likely that the writers of the gospels wrote about thirteen dining companions because that number was already considered unlucky, and possibly, too, because of its ties with the idea of sacrifice, especially of a male god or priest or his stand-in.

Robert Graves, especially in The White Goddess, claimed that the fear of thirteen came from ancient religious rituals in a matriarchal society where a male ruler (or god stand-in, or priest) would be sacrificed in the thirteenth month, often to have his blood sprinkled on the fields as a fertility rite. Naturally, the sacrificee and males in general would tend to have issues with that number! This is part of Graves’s theory of the sacrifice of a substitute taking the place of the intended victim (Abel, Enkidu, Remus, almost Barabbas, etc.)—a theory discredited by many scholars, but enthralling nonetheless.

So I wove those elements into the “last supper” scene of Dark of the Moon. My vision of the female-centered religion of the Minoans when it was in the process of being supplanted by the male-centered Greek religion reflects many of Graves’s theories, including the importance of the numbers twelve and thirteen (plus sacrifice of the king and other elements, many deriving from Leviticus).

And that’s all I’m going to give away about it!

Be sure to leave a comment for a chance at a signed copy of Dark of the Moon or one of my other novels of your choice! See a complete list here.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

December 8, 2012

12 Days of Books – Memories of Monet

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

I’m giving away a copy of CLAUDE & CAMILLE: A NOVEL OF MONET. The novel grew from my childhood; both my parents were artists. The easel, the drawing tale, the precious brushes and pens and curled tubes of oil paint were a natural part of my life. One day at the age of about thirteen my mother drew a beautiful reclining nude of me; unfortunately she hung it in the hallway so that boyfriends arriving to pick me up in the next few years got a good look at me. When I asked her to take it down, she exclaimed, “Are you ashamed of your mother’s art work?” (!)

I’m giving away a copy of CLAUDE & CAMILLE: A NOVEL OF MONET. The novel grew from my childhood; both my parents were artists. The easel, the drawing tale, the precious brushes and pens and curled tubes of oil paint were a natural part of my life. One day at the age of about thirteen my mother drew a beautiful reclining nude of me; unfortunately she hung it in the hallway so that boyfriends arriving to pick me up in the next few years got a good look at me. When I asked her to take it down, she exclaimed, “Are you ashamed of your mother’s art work?” (!)

CLAUDE & CAMILLE was not an easy book to write; it would not flow as a novel for a long time. It’s actually not easy to take a life which did not really have a plot and carve one from it. It went through many versions, including one which was greatly from the point of view of Claude’s friend Frédéric. But all my love for him was still poured into the final draft even if his scenes were curtailed to make way for more of the love story! And Camille turned out to be the most fascinating character.

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. She is currently working on several projects. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

12 Days of Books: Subscribe and Get Another Chance to Win!

By Holly Tucker (Editor, W&M)

Whether you’re a new reader or a die-hard Wonders & Marvels fan, WE NEED YOU to help us take our fancy new email subscription service through its paces.

Whether you’re a new reader or a die-hard Wonders & Marvels fan, WE NEED YOU to help us take our fancy new email subscription service through its paces.

We just decked out the email subscription options for the site. Now you can get automated feed updates via email at your choice of intervals (Monthly, Weekly, or Individual Posts).

You can also show your love for your favorite W&M contributors by subscribing to their personalized feed. You can get news about their latest books, behind-the-scenes updates on their research, or just a feed of their posts so you don’t miss a thing.

If you were a subscriber in the past, you’ll need to re-subscribe to our new feeds. But here’s a little motivation for everyone…

Subscribe between now at December 24 and you’ll be automatically entered into each of the “12 Days of Books” giveaways. Leave a comment for the giveaways that interest you most…and that makes double the chances of winning.

Have you seen the posts so far? We’ve got Adrienne Mayor’s book on Scorpion Bombs, Karen Abbott’s book on Chicago Madams, and my own book on the dark history of early medicine. A little bloodletting, anyone? And that’s just for starters, we still have 9 more to go!

On behalf of everyone here, THANK YOU SO MUCH for your continued support. This site is truly a labor of love, and it’s a delight to know that others share in our fascination for the past.

Warm wishes for a lovely holiday season!

All my best,

Holly

12 Days of Books: Walking Among Ghosts

By Holly Tucker (W&M Editor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

While researching this book, I traveled often to specialized library collections abroad and walked the streets of Paris and London to retrace the steps of my seventeenth-century doctors, patients, and killers. Most often, my strolls were an exercise of trying to imagine the past–rather than actually walking in it. Life and time move on. Physical spaces get repurposed, demolished, rebuilt. And to my great disappointment, Louis XIV will never greet me at the gates of Versailles. (More on that crazy fantasy here.)

While researching this book, I traveled often to specialized library collections abroad and walked the streets of Paris and London to retrace the steps of my seventeenth-century doctors, patients, and killers. Most often, my strolls were an exercise of trying to imagine the past–rather than actually walking in it. Life and time move on. Physical spaces get repurposed, demolished, rebuilt. And to my great disappointment, Louis XIV will never greet me at the gates of Versailles. (More on that crazy fantasy here.)

This was not the case at the Hôtel Montmor, the private residence where the main “character” of my nonfiction book did his horrific animal-to-human blood transfusion experiments.

I remember waiting for what seemed like hours one beautiful May day for someone to exit the soaring wood doors of the impressive compound on the Rue du Temple just so I could steal a peek at what lay behind. Once I finally gained access, I stood in the cour d’honneur, mouth agape and eyes watering. I was joyous…and overwhelmed.

Everything was precisely as I had imagined it after having worked so long with period maps, architectural plans, and descriptions in manuscript letters. The concierge of the building, Jean-Marie Carpentier, approached me cautiously, likely wondering if I were not a bit like the mentally-ill man that Baptiste used as one of his first transfusion patients.

As I explained in French (thanks to my French Grandmother, from whom I learned the language), the words came tumbling out in near gasps. Up there, that’s where Montmor’s private scientific Academy met. This is the staircase Denis walked up on the night of his history-making experiment. Under these dormers there is where Mauroy stayed after the transfusion.

After Monsieur Carpentier confirmed to my delight that the staircase, the balustrade, the tiles, all of it was in its original state, we spent the rest of the afternoon together exploring the building and what is left of the gardens–teaching each other about its rich history. As we strolled among the ghosts, I was reminded once again of how insanely grateful I am to get to the type of research I do as a researcher, teacher, and writer.

Holly Tucker is Professor of Medicine, Health & Society and Professor of French Studies at Vanderbilt University. Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist in Science & Technology. It was a Times Literary Supplement and Seattle Times Book of the Year. Her next book, on the early history of forensics, is under contract with W.W. Norton.

Holly Tucker is Professor of Medicine, Health & Society and Professor of French Studies at Vanderbilt University. Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist in Science & Technology. It was a Times Literary Supplement and Seattle Times Book of the Year. Her next book, on the early history of forensics, is under contract with W.W. Norton.

December 7, 2012

12 Days of Books: Lovely Little Lies

by Karen Abbott (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

“History is a set of lies agreed upon,” Napoleon Bonaparte famously said, and that adage stayed with me throughout the three years I spent researching Sin in the Second City, which tells the true story of two sisters who ran the world’s most famous brothel in early 1900s Chicago. Madams Minna and Ada Everleigh operated in a world where illusion was the most valuable currency, and, like most women in their profession, they were fantastic liars—especially when asked about themselves. The sisters tried on identities the way men in lesser houses tried on whores, picking over a lineup before selecting the prettiest one.

“History is a set of lies agreed upon,” Napoleon Bonaparte famously said, and that adage stayed with me throughout the three years I spent researching Sin in the Second City, which tells the true story of two sisters who ran the world’s most famous brothel in early 1900s Chicago. Madams Minna and Ada Everleigh operated in a world where illusion was the most valuable currency, and, like most women in their profession, they were fantastic liars—especially when asked about themselves. The sisters tried on identities the way men in lesser houses tried on whores, picking over a lineup before selecting the prettiest one.

During my research I discovered a 1989 letter from a Virginia woman named Evelyn Diment to the writer Irving Wallace, who had published a novel and an essay about the Everleigh sisters. “Dear Mr. Wallace,” it began, “In your author’s note, you write at some length about your meeting and friendship with the Everleigh sisters… almost all of what they told you was a fabrication of the truth (a total lie), I know, because these two women were my Great Aunts. The real truth of their career beginnings were sordid and they were subjected to degradation, not even spoken about ever until the last several years.”

I found this letter in 2006 and began a frantic search for Evelyn Diment in the hope that she was still alive, writing to every Diment I could find in directories, public records, and archives. I had just about given up when I received a phone call from a man who introduced himself as William Diment.

“I have Evelyn Diment right next to me,” he said. “She’s my great aunt, and she’s 85. Would you like to speak with her?”

“Yes!” I said (and silently added, “And please hurry because she’s 85!”)

And so Evelyn proceeded to fill me in on the truth—as best as she knew it—of the sisters’ real history. They hailed not from the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia but from Bluegrass Country down in Louisville, Kentucky. Yes, their father had once been a wealthy lawyer, but he had lost all of his money during the Civil War. The sisters did join a traveling stock company, but they hadn’t, as they’d claimed, traded the stage for the red light district by chance. Instead their desperate father pushed them into prostitution so they could help support the family. “They made a marvelous success out of it,” Evelyn said. She concluded our conversation by saying that the sisters valued discretion above all else, and never told the truth for fear of shaming their family.

After the book was published in 2007 I heard from numerous readers who had a connection to either the Everleigh sisters or to Chicago during that time. One man told me that his grandfather was a lookout man for Big Jim Colosimo, a gangster who operated a nearby brothel and befriended the sisters. At one reading, a little old lady—she had to be in her 80s—hobbled up to me on her walker. She looked to her right, then to her left, and then leaned and said, very quietly, “My aunt was a whore.” The caretaker of St. Paul’s Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia, where the sisters are buried, grew so enamored with their story that he bought a plot for himself right next to their graves.

But my favorite stories came from a man named William Self, a prominent television and movie producer whose fascination with the Everleigh sisters began when he attended the University of Chicago in the early 1940s. He started corresponding with Minna and Ada, who sent him incredible relics from their lives: a glass ashtray imprinted with Minna’s photograph; a copy of Minna’s novel, Poets, Prophets, and Gods; and even Minna’s old bed. He tried to visit them in New York but the sisters always refused. When Minna died in 1948, Ada moved to live with a relative in Virginia. In 1957, three years before she died, the 93-year-old former madam invited Will and his wife to visit her.

During dinner in Ada’s kitchen they discussed the weather and the latest movies. Will was getting impatient; he longed to ask questions about the old days in Chicago but didn’t want to offend his host. Eventually his wife excused herself and went to bed. As soon as they were alone, Ada leaned forward and said, “I know you’ve been dying to ask me about the Everleigh Club, so this is your chance.”

Will considered what to say. He might only get a single question, so it had to be a good one. He recalled one of the most famous legends about the Everleigh Club: that Marshall Field Jr., son of the department store scion, was shot in its parlor during a fight with a prostitute. He asked, “Is it true that Marshall Field Jr. was shot inside the Club?”

Ada thought for a moment. She smiled and replied, “No, dear, but we bought all of our furniture in his store.”

It was a lie, Will knew, and the best one he’d ever heard.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her next book, a true story of four female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins in 2014.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her next book, a true story of four female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins in 2014.

December 6, 2012

12 Days of Books: How to Make a Scorpion Bomb

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

To celebrate the holidays and 3 years of Wonders & Marvels, we’re giving away 12 signed copies of books by our regular contributors. If you’d like a signed copy of this book, please leave a comment below. Winners will be announced on December 24.

Morbid delight, horror, and melancholy—conflicting moods shaped my research into the amazing arsenal of diabolical biological and chemical weapons that were used in antiquity. Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World seems to evoke mixed emotions in readers, too. The sheer number of natural forces that could be weaponized thousands of years before modern technology and scientific biochemical advances is very sobering. Yet it’s difficult to suppress appalled laughter at the images of terrified Romans on siege ladders fending off a rain of clay pots filled with live scorpions, or the horrible last resort of deploying shrieking flaming pigs to send an invader’s war elephants amok.

The enthusiastic responses from readers and the media were gratifying but sometimes disturbing. Countless parents told me that their twelve-year-old boys (and some girls) loved the recipe for making scorpion bombs, the live “grenades” that had saved the ancient desert city of Hatra from the besieging Roman army of Emperor Septimius Severus in AD 198-99. Visions of homemade spin-offs troubled my conscience, imagining kids gleefully lobbing baby-food jars filled with hapless spiders, wasps, fire ants, etc at school bullies. It turned out that grown-ups were just as devilishly attracted to the notion of re-creating ancient biochemical weapons. I had to remind History Channel TV producers, for instance, to don gas masks when they replicated toxic fumes devised by the ancient Spartans.

My study of ancient weapons of mass destruction first came out in 2003, at the start of the Iraq War against Saddam Hussein, ensuring a timely edge. The ruins of Hatra fortress are near modern Mosul, Iraq, where US troops were searching in vain for Saddam’s (nonexistent) weapons of mass destruction. Amid this tension, Newsweek published a sham report announcing that evidence of WMD had been discovered near Mosul—only revealing in the last sentence that the source was actually my account of ancient scorpion grenades.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2003/10/05/wmd-they-re-history.html

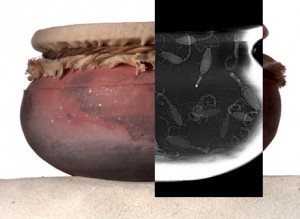

The dread scorpion bomb was selected for National Geographic’s special Poison issue, “Twelve Toxic Tales.” (2005). The editors decided to make a historically accurate, real scorpion bomb to illustrate the story of Hatra’s unique biological defense weapon. An expert in ancient pottery created an authentic replica of a terracotta jar found in the ruins of Hatra. After diligent searching they obtained, from an exotic pet shop in Rhode Island, a dozen live Iraqi Death Stalker scorpions, scrabbling about in a plastic takeout container.

Then, in the National Geographic studio, photographer Cary Wolinsky and scorpion wrangler Fred SaintOurs found themselves facing the same dire threat of “blowback,” a perennial dilemma for all who resort to biological weapons, that the defenders of Hatra had somehow overcome.

How does one safely stuff several annoyed and agitated giant scorpions into a jar? In antiquity the common technique was to verrrrrry carefully spit on the business end of the scorpion. But that requires nerves of steel and perfect aim. Resorting to a method unavailable to the ancient desert-dwellers in Iraq, they placed the scorpions in a refrigerator to induce torpor before each photo session. The resulting photograph and X-ray of the replica scorpion bomb of Hatra was a smashing success and one of my favorite souvenirs of this book.

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0505/feature1/assignment2.html

About the author: Adrienne Mayor, Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford, is the author of Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World (rev ed 2009); and The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy, a National Book Award nonfiction finalist.