Holly Tucker's Blog, page 75

November 20, 2012

Ariadne, Theseus, and the reader—and a giveaway!

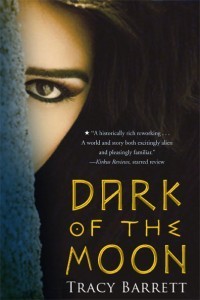

Recently an interviewer asked me why young readers would be interested in historical fiction, specifically, how a teenage girl today could relate to Ariadne, the priestess of the moon-goddess (and future goddess herself) in Dark of the Moon. The story is set in the Bronze Age, after all—how much can a modern sensibility resonate with it?

This was an odd question to me—and I imagine it’s also odd to most readers of this blog—so I found it hard to answer. But I’ve had the chance to think it over, and if I were to be asked the same question today, I’d probably answer something like this:

We sometimes need a little remove from our own time, place, and circumstances in order to understand them. It’s similar to the way studying a foreign language helps you better understand how your own language works. We’re just too close to our own language—and our own setting—to be able to see it clearly. But if we step back a pace, we quiet what Lionel Trilling called “the buzz of implication.” Our own issues come into focus in a different (not necessarily better, just different) way from a different vantage point.

Ariadne faces a struggle that many people face: She agonizes over whether she should she do what is expected of her, or forge her own path. She’s also conflicted about how much she owes to her family, her faith, her country, and how much she owes to herself. And on a more personal level, does she love Theseus, or is she merely swept off her feet by the first boy who sees her as a girl and not as a goddess-to-be?

King of Ithaka is also set in the past (in this case, the Iron Age). My protagonist, Telemachos, lives in a time of war, and he has to discover how to be a man despite an absentee father. Tell me those aren’t common issues of young men in many countries today!

I don’t write for a didactic purpose; I don’t expect my readers to take Ariadne or Telemachos as a model for their own behavior. But—to go back to the language analogy—just as studying dangling modifiers in Latin can help us recognize them in English, seeing how characters in historical fiction (or fantasy or science fiction) confront familiar issues might lead to a clearer understanding of the reader’s own questions and conflicts.

Giveaway! Leave a comment for a chance to win a copy of the newly-released paperback of Dark of the Moon! Winner chosen at random from commenters on November 27.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

November 18, 2012

Ibn Who?

by Pamela Toler

Ibn Khaldun on the Tunisian 10 dinar note. Image courtesy of http://www.banknotes.it

If you spend any time studying history in a serious way–whether in school and/or as a dedicated history nerd–you end up with a list in your head of Great Historians of the Past: Herodotus, Thucydides, Tacitus, the Venerable Bede, Gibbon, Macaulay, Prescott. Even after their historical works were revised or even rejected by later scholars, they remain as monuments of thought, analysis, and masterful story telling.

I had finished my graduate school coursework and was well into my dissertation before I added fourteenth century Arab historian and social observer ibn Khaldun to my personal list of history all-stars.

Ibn who? I thought you’d never ask.

Ibn-Khaldun is sometimes seen as the last great scholar of the Islamic golden age, now considered by those in the know as one of the founders of modern historiography, sociology, and economics. He was born in Tunis in 1332 to an Andalusian family of scholars and officials who had fled Spain after Seville fell to Ferdinand of Castile in 1248. ( NOT the Ferdinand of Ferdinand and Isabella. The Christian reconquest of Spain took several centuries. ) When he was seventeen, his parents and teachers died in the Black Death, as did almost half the population of Europe and Asia.

Like many others caught in the chaos that followed the Black Death, ibn Khaldun left his home in search of something: stability, a career, adventure, a life. He was well educated and had no trouble finding work in the courts of North Africa and Islamic Spain. Although he claimed that he wanted to devote his life to scholarship, he repeatedly became entangled in court intrigues thanks to either bad luck or bad judgment.

In 1375, after he failed to save a friend who was tried and executed for heresy, ibn Khaldun withdrew to the Castle of ibn Salamah, near Oran in Algeria, to immerse himself in his books and try to make sense of his experiences. During his years of retreat, he completed what would be his best-known and most original work: the Muqaddima, or Prolegomenon. Intended as the first volume of history of the Arab peoples, the Muqaddima is an introduction to the writing of history and a discussion of the nature of the state and society. In it, he explores the idea that writing history is an act of interpretation and suggests a rigorous process of fact checking as a necessary part of the work.

The most important part of the book is the Islamic equivalent of Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Drawing on his personal and family experience and the history of the Arab world, ibn Khaldun analyses how civilizations breed their own decline, moving from strength to luxury to moral laxity and decay. Historian Arnold Toynbee, himself the author of a twelve-volume study of the rise and fall of civilization, described the Muqaddima as “undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever yet been created by any mind in any time or place…the most comprehensive and illuminating analysis of how human affairs work that has been made anywhere.”

After four calm years at the Castle of ibn Salamah, ibn Khaldun needed conversation and a research library so he could work on the main body of his history. He returned to Tunis, where he was immediately sucked into the usual morass of academic, religious and political intrigues. He escaped Tunis under the pretext of going on the hajj, only to fall into similar turbulence in Cairo. Over the course of twenty-five years, the sultan appointed him as a judge and subsequently dismissed him six times.

In 1400, ibn Khaldun was given another chance to help write history, this time as a source. The sultan of Cairo insisted that he join a delegation to Damascus to negotiate with the renowned Mongol conqueror, known in the west as Tamurlane. When the delegation received word of the rebellion back in Cairo, they returned to the west, leaving ibn Khaldun behind in the besieged city of Damascus. The historian was determined to meet with the renowned conqueror. Since the gates of the city were locked, he had himself lowered over the walls in a basket. Ibn Khaldun met with Timur several times over the course of the month, enjoying wide-ranging conversations about history, North African culture and Timur’s conquests. Ibn Khaldun recorded those conversations, as well as a first hand account of the siege of Damascus in his autobiography, now a major resource for anyone writing about Timur.

Ibn Khaldun returned in Cairo in 1401 and resumed the cycle of appointment and dismissal. He died there five years late.

A version of this post previously appeared in History in the Margins

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change. She is the author of Mankind:The Story of All of Us–a companion book to the History Channel series.

November 14, 2012

Does my culus look big …? Bizarre Roman Beauty

Magnusne culus meus in hac videtur?

‘Does my bottom look big in this?’

A first century Roman woman would have asked this question hoping for the answer maximē! (You bet!)

Ideals of female beauty have always varied throughout the centuries, from the well-padded women of Rubens’ time to the androgynous flappers of the 1920′s to the late 20th century Playboy centerfold with big breasts and slender thighs. So it should come as no surprise that Romans of the first century AD had their own ideas of beauty.

The first thing you notice when looking at Roman female nudes is the number of nymphs and goddesses with small bosoms. “I fear big-breasted women”, wrote the first century poet Martial (14.66). Yes, he was a notorious woman-hater and yes, he was writing this from the point of view of an item of clothing, but in another epigram (14.134) he reminds us that the perfect breast could be cupped in a hand.

His attitude is reflected in surviving frescoes from the first centuries BC and CE.

Flip through any glossy book about Pompeii, or do a Google image search for Roman-fresco-nudes, and you will see that the women (goddesses mostly) almost always have generous rumps and thighs. In the notorious room of the Archaeological Museum of Naples called the Gabinetto Segreto or “Secret Cabinet” – where you find the most erotic Roman art – you will see that the sexiest women have the biggest bottoms.

Another erotic element of the ideal Roman woman is her pale skin. The contrast between the tanned body of a man (or giant) the milky skin of a woman (or nymph) created an erotic frisson. At the top of this post is an extremely sexy fresco of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus embracing the nymph Galatea.

Does her bottom look big in that? Maximē!

Another erotic work of the first century AD – a literary one this time – describes the face of an ideal woman. As my free translation of Satyricon 126 below shows, Petronius’ paradigm of female loveliness has a low forehead, aquiline nose and monobrow.

No speech could describe her beauty; whatever I say would be less than the whole. Her naturally curly hair springs from a narrow forehead to flow tumbling back over her shoulders. Her eyebrows run right from the edges of her cheekbones and almost meet above her eyes. And what eyes! They are brighter than stars sparkling in a moonless night. Her nose is slightly hooked and her little mouth as kissable as Praxiteles’ Diana. She outshines the whitest marble with the milky brightness of her chin, her neck, her hand, even her foot in its gilded sandal. (Satyricon 126.15ff)

Pasty skin, low forehead, strong nose, monobrow, small breasts, big bottom… These were the ideals of female beauty in first century Rome!

But in any age or era, the most discerning lovers will always look beyond surface to inner beauty. The famous love-poet Catullus is such a one when he dismisses the superficially beautiful Quintia in favour of his vivacious girlfriend Lesbia.

Everybody thinks Quintia is a beauty. I admit she is fair of skin and tall with graceful carriage. But I wouldn’t call her “beautiful”. She is not a bit sexy, doesn’t have a grain of wit in her whole statuesque body. Now Lesbia, she’s beautiful, and so amazing that she strips every bit of sexiness from every other woman. (Catullus 86)

The moral of the story is a timeless one. Don’t worry about whether you meet the ever-changing requirements for physical attractiveness, but find lovers and friends who will appreciate your inner beauty.

Caroline Lawrence writes Roman adventures for children aged 7 – 14, so was glad of the opportunity to talk about a subject she usually doesn’t tackle in schools.

November 9, 2012

Women and humour in history

Do men always get the best punch-lines?

I was recently at a conference where one of the speakers illustrated his points about gender in ancient Rome by referring to a story about Winston Churchill and Nancy Astor. Quick-witted, the first woman Member of Parliament, Nancy Astor’s reputation has been tarnished by her support of Chamberlain’s policy of appeasing Hitler. Both Winston and his wife Clementine made a number of scathing remarks about her which have been preserved: in 1942, after a highly unfortunate speech in which Nancy belittled the Russians at the very point when they were fighting the Battle of Stalingrad, Clementine commented to her husband that ‘Nancy Astor has made a clumsy & ungracious (I was about to write “ass of herself” – But I will not compare her to the animal which bore Christ in triumph) speech which has repelled everybody’.

The remark that was quoted at the conference was one of the greatest put-downs of modern times. Nancy allegedly said to Churchill, ‘Sir, you’re drunk!’ Churchill is supposed to have replied, ‘Yes, Madam, I am. But in the morning, I will be sober and you will still be ugly.’ This story has achieved mythical status, but it has ‘stuck’ to Nancy even though it may have been not her, but the Labour politician Bessie Braddock, who said this to him, perhaps in the House of Commons bar, or at a party. Another such story has it that, at Blenheim Palace, Nancy said to Churchill, ‘If I were your wife I would put poison in your coffee’. Winston responded with, ‘Nancy, if I were your husband, I would drink it.’ This one too has taken on legendary status, and is also linked to Lloyd George, who was supposed to have said it to a suffragette.

In these stories, the man gets the best lines: humour appears to be about putting down uppity women. But there are also lots of witty remarks attributed to Nancy; for example, ‘I married beneath me — all women do’, ’One reason I don’t drink is that I want to know when I am having a good time’ and ”I refuse to admit that I am more than 52, even if that makes my children illegitimate.’

That last one in particular makes me think of the emperor Augustus and his daughter Julia.  A sense of humour was one of the features of Augustus that the biographer Suetonius singled out: his idea of a joke was apparently to give out worthless presents wrapped up and labelled to look a lot more promising than they really were. Hmm! It’s Julia whose jokes really work today. She comes across in the sources as feisty, wayward, and always ready to answer back. After giving some more examples of Augustus’ jokes, Macrobius – who wrote around 400 AD – preserves a list of Julia’s comments. The best one, for me, is her answer when people who knew she had been sleeping around commented that they were surprised that her sons came out looking like Agrippa, her then-husband. She said, ‘I never take on a passenger unless the ship is full’ – so, she was using pregnancy as a form of contraception.

A sense of humour was one of the features of Augustus that the biographer Suetonius singled out: his idea of a joke was apparently to give out worthless presents wrapped up and labelled to look a lot more promising than they really were. Hmm! It’s Julia whose jokes really work today. She comes across in the sources as feisty, wayward, and always ready to answer back. After giving some more examples of Augustus’ jokes, Macrobius – who wrote around 400 AD – preserves a list of Julia’s comments. The best one, for me, is her answer when people who knew she had been sleeping around commented that they were surprised that her sons came out looking like Agrippa, her then-husband. She said, ‘I never take on a passenger unless the ship is full’ – so, she was using pregnancy as a form of contraception.

Until very recently, women weren’t stand-up c0mics, because they just weren’t seen as ‘funny’. Part of this must be about the confidence to speak in front of an audience. Part of it concerns the lack of role models. And there are still many jokes around that assume that women lack a sense of humour – like the lightbulb joke, ‘Q: How many feminists does it take to change a light-bulb? A: ‘That’s NOT FUNNY!’ But recent books, like Yael Cohen’s We Killed, usefully trace the rise of the female comic; the daughters of Julia are alive and well today!

J.P. Wearing (ed.), Bernard Shaw and Nancy Astor (2005)

Y. Cohen, We Killed. The Rise of Women in American Comedy (2012)

The Censorship of Titicut Follies

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Disturbing images fill the screen: a man confesses to sexually abusing his daughter, guards taunt a mental patient until he screams, a physician thrusts a grimy tube down a man’s throat for a force-feeding. These are some of the unforgettable scenes in Titicut Follies, a documentary by that 45 years ago sparked one of the strangest censorship controversies in U.S. history.

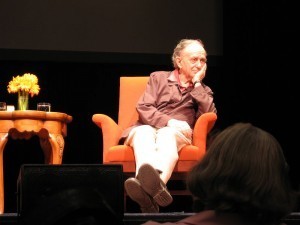

Titicut Follies director Frederick Wiseman in 2005

Without narration or much editorializing, Titicut Follies chronicles events at Bridgewater State Hospital in Massachusetts, an institution for the criminally insane. Sandwiching the vignettes of cruelty and neglect are close-up shots from an annual cabaret in which patients sing and dance to tunes from Tin Pan Alley — the follies of the title. By bringing his film crew to the hospital, Wiseman contributed to a long tradition of reformers seeking to expose the deficiencies of places of confinement for the mentally ill.

Before him, the intrepid reporter Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Cochran) had shammed illness and gained commitment to Bellevue Hospital in New York. She documented the mistreatment of patients and the ignorance of doctors in her 1887 book Ten Days in a Mad-House. Twenty years later, a psychiatric patient named Clifford Beers wrote A Mind That Found Itself about his sufferings during treatment in a series of asylums. The book inspired reform. “Bedlam,” Albert Maisel’s famous 1946 LIFE magazine article detailing atrocious conditions in several institutions, produced outrage and changes. Throughout the past century, many other patients, reporters, and healthcare workers have similarly shed light on barbaric conditions in psychiatric hospitals.

Wiseman made Titicut Follies in cooperation with Bridgewater’s administrators, who wanted to demonstrate their need for more funding from the state, but Massachusetts officials responded by obtaining a legal order preventing its premiere screening. The court’s injunction cited violations of the patients’ right to privacy — the first time such a right had ever been asserted as a reason for censorship, thus marking the only instance in American history in which the government suppressed a creative work for a reason other than national security, obscenity, or immorality. Many people noted the irony that accusations of exploiting psychiatric patients had targeted a movie about the exploitation of those very patients. In 1968, a Massachusetts judge ordered the destruction of all copies of the film.

The following year, the state’s Supreme Judicial Court overruled that draconian order, replacing it with a requirement that only physicians, lawyers, judges, healthcare workers, and social workers be allowed to view the documentary. That condition held until 1991 (although presenters often subverted it), when the deaths of many of the patients in the movie had made the issue of privacy moot. A Superior Court judge ruled that the public could freely view Titicut Follies for the first time.

One of the judges who ordered the censorship of Titicut Follies complained that the film was faulty for forcing viewers to make their own interpretations of ethically troublesome scenes. That, Wiseman replied, was his intention all along.

SOURCES:

Anderson, Carolyn. “The Conundrum of Competing Rights in Titicut Follies.” Journal of the University Film Association, Winter 1981. Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 15-22.

Appelbaum, Paul S. “Titicut Follies: Patients’ Rights and Institutional Reform.” Hospital and Community Psychiatry, July 1989. Vol. 40, No. 7, pp. 679-680.

Lopate, Phillip. “Composing an American Epic.” The New York Times, January 23, 2000: 2.11.

Walker, Jesse. “Let the Viewer Decide.” Reason, November 16, 2007.

November 6, 2012

Ancient Amazons’ Massage Oil

by Adrienne Mayor (a Wonders & Marvels contributor)

by Adrienne Mayor (a Wonders & Marvels contributor)

The next time you bathe in an icy river of southern Russia, like the Amazons of classical antiquity, be sure to warm up afterwards with the Amazons’ secret massage oil.

The women warriors known to the ancient Greeks as Amazons dwelled north of the Black Sea around the Don River in southern Russia. In antiquity the Don was known as the Amazon River, because the Amazons used to bathe there. Amazons were women of Scythian tribes, nomadic horse people who crisscrossed the vast steppes from the Ukraine to Mongolia. These people were known in antiquity for their endurance and ability to withstand wintry temperatures and snow. Ancient Greek vase paintings depict the distinctive woolen leggings and tunics, leather boots, hats with earflaps, and animals skins worn by Amazons and Scythian warriors. Those articles of clothing designed for cold weather, along with weapons, have been found in graves of real women warriors of Scythia, who lived in south Russia and Siberia 2,500 years ago.

The Amazons’ secret weapon against freezing temperatures was mentioned in an obscure treatise, “On Rivers” by Pseudo-Plutarch. Along the Amazon (Don) River where the Amazons used to bathe “grows a plant called halinda, like a colewort. Bruising this plant and anointing their bodies with the juice makes one better able to endure the extreme cold.”

What was this mysterious folk remedy for warming the body in ancient Scythia?

Pseudo-Plutarch gives a clue for identifying the ancient Scythian word halinda by comparing it to colewort, cabbage. A little botanical detective work reveals that the halinda plant was probably Brassica napus, a hardy wild winter cabbage of Russia and Siberia, related to Brassica oleracea. These coleworts are the ancestors of today’s edible cabbages, kale, collards, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and cauliflower (and rapeseed/canola oil). The cruciferous plants were first cultivated about 2,500 to 4,000 years ago, bred to reduce the amount of mustard oils, sulfur-containing glucosinolates, which give this species their pungent, bitter taste. Crushing wild cabbage yields a lot of mustard oil, which is an irritant. Rubbed on the body as a massage oil, it is a strong stimulant of circulation, bringing blood to the skin surface, causing a warm sensation and alleviating aches and pains of arthritis (a common affliction of Scythians, as studies of their skeletons show). The analgesic action of wild cabbage is similar that of capsaicin, the irritant oil from hot chili peppers from the New World, applied as a topical ointment to relieve arthritis and other pains. The Amazons of ancient Scythia would also have benefited from cabbage oil’s antibacterial properties, as a poultice for wounds, and it was useful in summer for repelling insects.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

October 30, 2012

Dinner at Oxford with the World’s Greatest Elizabethan Scholar

by Stephanie Cowell

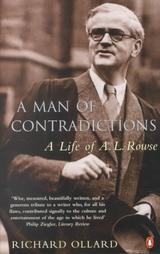

He came up the stairs of the community room in Jesus College Oxford one July afternoon asking for me by name for we had been corresponding for a time. He was Dr. A.L. Rowse, then in his mid-eighties and generally acknowledged to be the greatest Elizabethan scholar in the world. He was irascible and short tempered. He was unequalled in his field and he knew it; in short, he was terrifying.

I was 42, a divorced mom of two boys from New York City, working in an administrative position to support them. I had never gone to college, but read history and literature extensively. I wanted to write novels about the Elizabethans. I wanted to prove to the world that I was more than a secretary. It was the annual summer conference at Oxford of the English Speaking Union, and thirty-six winners from branches around the world had been granted scholarships to attend for ten extraordinary days, to live in the 16th century college less than a minute’s walk from the Bodleian Library. Dr. Rowse was our major lecturer.

I had discovered his writing about the Elizabethans while researching my first novel about a boy actor and his spiritual and scientific search. Somehow I found Dr. Rowse’s address in Cornwall and wrote him. “Optimistic, aren’t you?” a friend said. “He’s not very young.” And then a few weeks later his light blue letter lay on my doormat. After that, I won my scholarship to meet him.

I think there were no more halcyon days in my life than those warm days at Oxford. We dined in the wainscoted hall under the portrait of the great Queen Bess and attended lectures on all aspects of the British world, including a trip to Stratford and afternoon tea in the gardens of Rhodes House. I felt I had come home. I sat at high table in hall with Dr. Rowse, and in the Jesus College quad, and walked by his side in All Souls. I loved everyone. I loved Oxford. I loved every stone, every chapel, every bookshop. I walked in the history I had long read.

The other students left us alone; they were all terrified of him. I was too much in love to share their wariness. He was known for his terrible temper; to me he was only courteous. We talked about writing historical novels and he gave me historical advice. He also loved this place. He had written, “I loved Oxford because there I found my true self.”

After I left, his light blue air mail letters continued to reach me. I published two Elizabethan novels, Nicholas Cooke and another dedicated to him; I begged more advice. I addressed him as Dr. Rowse. He signed his letters, love, A. L. He gave me gracious blurbs for my books.

And then one day the letter from his address was in a regular envelope and not in his hand. It was from his nurse saying he had had a serious stroke at the age of 93 (he had completed two books the previous year) and could no longer write. Then a time later I opened the New York Times and saw that he had died. I was stunned. I was but one of thousands of people who adored him; how could he know how much I had loved him? And how could I ever thank him for taking time from such a brilliant life to encourage me?

It was wanting to meet him that brought me to Oxford. I touched a life that under other circumstances might have been mine and I cherished its values of hard work and tradition. Like A.L Rowse, I also loved Oxford because it was there I found my true self.

I find Dr. Rowse’s light blue letters around the house now and then. Somehow they are never all in one slim folder. I have no degrees from my ten days as an Oxford woman but it has stayed in my heart. The beauty of my days there remains in me forever and reminds me that for a very brief time I touched what was dearest in excellence to me and now for all my life it remains part of all that I do.

___________________________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com

A Botanist, a Butcher and a Body: Encountering an Eighteenth-Century Vrykolakas

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

From 1700-1702, French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort journeyed through the Greek islands and Constantinople. The following tale is his account of a Greek revenant (vrykolakas) on the island of Mykonos (A Voyage into the Levant, vol. 1, 1718).

The story begins with the unsolved murder of a local “ill-natur’d and quarrelsome” peasant. Two days after burial, the man’s apparition was seen walking around the town at night. He “rumbled about Peoples Goods, put out their lamps, griped tem behind, and a thousand other monky Tricks”—a source of amusement until the “better sort of People” began to complain. Important townsfolk, monks and priests soon came to a conclusion: they would say a mass and pull out the corpse’s heart to drive out the demon.

The town butcher, “an old clumsy fellow”, was the one in charge of removing the heart. Tournefort noted that the butcher initially opened the corpse at the belly, then groped around the entrails in search of it, until someone suggested he instead try the chest cavity. It was a smelly process and the observers burned frankincense to cover it. This was an error, according to Tournefort, describing that “the smoke mixing with the Exhalations from the Carcass, increas’d the stink, and began to muddle the poor people”. The result? “Their Imagination, struck with the spectacle before them, grew full of Visions.” Suddenly, “they were incessantly bawling out Vroucolacas”—a cry of horror that spread rapidly throughout the town.

The butcher reported that the body was still warm and insisted that the blood smeared on his hands was bright red. Those who had carried the corpse recounted that the body was not stiff. Tournefort sceptically added that “I don’t doubt they would have sworn it did not stink, had not we been there”. Tournefort and his companions tried to explain why the decomposing entrails might have felt warm, commenting that the blood on the butcher’s hands didn’t seem especially red. But nobody listened.

The town authorities decided to burn the heart on the sea-shore, but the haunting continued, until everyone was “frighted out of their senses”. The vrykolakas took to beating people, breaking doors, windows and roofs, tearing clothes and, worst of all, emptying all the bottles and vessels around. “’Twas the most thirsty Devil!” commented Tournefort.

Confronted with this “Epidemical Disease of the Brain” (something I’ve blogged about previously), the botanist and his friends held their tongues, knowing that they were likely to be accused of being atheists or infidels. Although they recommended that the local authorities keep watch for the “vagabonds” behind the troubles, the solution was increasingly clear to the townspeople. They had not properly disposed of the body. On January 1, 1701, the Devil finally met his match in the townspeople who lit a “Bonfire of Joy” to burn the corpse. Peace was finally restored to Mykonos.

The account tells us much about folklore beliefs in the region. The vrykolakas has much in common with both the vampires of eastern Europe and the ghosts of western Europe. Like vampires, the revenant had been a difficult person in life; the only way to be rid of the problem was through correctly disposing the body. The vrykolakas was also typical of many early modern vampires in that blood drinking was not a part of the story (although the revenants were often thought to have great hunger and thirst, as this one did…). Like ghosts, the revenant potentially had some form of unfinished business—although nobody seemed bothered about finding the murderer.

Tournefort also reveals much about the growing division between popular belief and scientific knowledge, particularly in terms of evidence. The botanist and butcher both looked at the body, but had very different explanations. The botanist identified problems in butcher’s examination and conclusions, and could provide an obvious rational explanation (vagabonds) for most of the problems. The butcher, in contrast, interpreted the case within an entirely different worldview, entirely supported by the lay and religious authorities, in which the troublesome living inevitably made for troublesome dead.

Tournefort, of course, appears as a logical and rational person to our modern eyes. But for the people of Mykonos, his explanation made no sense. It was Tournefort who would have seemed “full of Visions”!

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and recently taught a course on natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe. She also blogs weekly on history of medicine and science at her Sloane Letters Blog.

October 23, 2012

Uncommon Soldiers: Women in the Civil War

Sarah Emma Edmonds served in the Union army as Private Frank Thompson.

By Karen Abbott (W&M Contributor)

In the fall of 1862, at an Union army encampment along the Rappahannock River, a corporal in a New Jersey regiment, serving picket duty, began moaning and doubling over in pain. At first his comrades dismissed his complaints, but when he sank to his knees, unable to support himself, they carried him to a nearby farmhouse used as an army hospital. “There,” a fellow soldier reported, “the worthy corporal was safely delivered of a fine, fat little recruit for the regiment!” Another joked, “It is not a bad move of the government if they can make the corporals bear children and serve as a soldier they may keep the stock up.” The woman, whose name has been lost to history, had managed to conceal both her pregnancy and her sex during her year of service.

She was not alone. Six soldiers are known to have performed their military duties while pregnant, with none of their comrades noticing their condition until they went into labor, and as many as 400 women, in both North and South, disguised themselves and fought as men. Some joined the army with a husband, brother, sweetheart, or father; one couple even enlisted together on their honeymoon. Some, like a 12-year-old girl who joined as a drummer boy, were fleeing an abusive home situation. For poor, working-class, and farm women, the bounties and pay ($13 per month for Union soldiers, $11 per month for Confederates) served as an incentive. A small number of women were living as men prior to the war and felt the same pressure as men to enlist. One Northern woman was a staunch abolitionist who fought because “slavery was an awful thing” A Southern counterpart sought adventure, yearning to “shoulder my pistol and shoot some Yankees.”

Official protocol of both the U.S. and Confederate war departments dictated that all recruits strip and undergo a thorough physical examination, but doctors across the country flouted these rules. They had quotas to fill and needed bodies, quickly. It didn’t matter if a recruit was prone to convulsions or deaf in one ear or suffering from diphtheria. He merely required the strength to carry a gun, a trigger finger, and enough teeth with which to tear open powder cartridges. One recruit recalled the doctor pinching his collarbones and asking, “You have pretty good health, don’t you?” before passing him. Another was welcomed into the army after receiving “two or three little sort of ‘love taps’” on the chest.

Certain aspects of Victorian society and mid-19th century military life aided the women’s masquerade. Men were accustomed to seeing women in crinolines and bonnets and had no concept of what one would look like wearing trousers and a kepi hat. They went for long stretches of time without bathing or changing. To save time to prepare for roll call in the morning most of the officers remained partially clothed for bed; some even turned in wearing coats and boots. The stress and physical demands of a female soldier’s new role would almost certainly stop her menstrual cycle, and if she did bleed her soiled rags could be passed off as the used bindings of a minor injury—hers or someone else’s. Smooth faces and high-pitched voices could be attributed to youth. Male soldiers who knew or suspected there was a woman in the ranks were usually impressed by her patriotism and bravery, and chose to keep her secret.

Some women soldiers served out their entire enlistments without being detected, but the majority weren’t so fortunate. A careless few betrayed themselves through stereotypical feminine behavior. Two women serving with the 95th Illinois Infantry were outed when an officer threw apples to them. They were dressed in full military uniform, but instinctively made a grab for the hem of their nonexistent aprons in order to catch the fruit. Another woman was suspected when a commander witnessed her giving “a quick jerk of her head that only a woman could give.” A recruit in Rochester, New York forgot how to don pants, and tried to put hers on by pulling them over her head. Illness was the greatest threat. Numerous women suffering from common ailments—typhoid, measles, malaria, pneumonia, dysentery, and smallpox—declined treatment rather than risk a medical examination.

Some women, fearing discovery and its consequences—which ranged from dishonorable discharge to being put on nurse detail to arrest and imprisonment—preemptively left the army. Sarah Emma Edmonds, better known as Private Frank Thompson to her comrades in the 2nd Michigan, enlisted shortly after the Fall of Fort Sumter and served with distinction as a nurse, soldier, and spy. For two years she successfully concealed her sex and self-treated various ailments, including a broken foot and badly mangled arm, but in the spring of 1863, fighting a severe bout of malaria, she saw no choice but to desert. “Had I been what I represented myself to be, I would have gone to the hospital and had the surgeon make an examination of my injuries, and placed myself in his hands for medical treatment and saved years of suffering,” she later wrote. “But being a woman I felt compelled to suffer in silence and endure it the best I could… I would rather have been shot dead, than to have been known as a woman and sent away from the army under guard as a criminal.” She slipped away from camp in the middle of the night, and never called herself Frank Thompson again.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her next book, a true story of four female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins in 2014.

Sources: Elizabeth D. Leonard, All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies. New York: Penguin Books, 1999; DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War. New York: Random House, 2002; Laura Leedy Gansler, The Mysterious Private Thompson: The Double Life of Sarah Emma Edmonds, Civil War Soldier. New York: Free Press, 2005.

October 22, 2012

A History of Diffusing Useful Knowledge

By Marc Merlin (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK): a title which sounds simultaneously so noble and yet so understated that it has to be either a Monty Python concoction or the actual name of an 19th century British organization dedicated to the advancement human civilization. It turns out that the latter is the case. The SDUK, founded in London in 1826, sought to educate citizens with limited access to formal instruction, notably with the publication of its weekly illustrated The Penny Magazine.

I’ve encountered references to the SDUK in my reading over the years, but never gave it much thought. A few months back a mention in Randal Keynes’ Darwin biography Annie’s Box brought it to my attention again. This time, though, it occurred to me that, as the Director of the Atlanta Science Tavern, I’m pretty much in the business of diffusing useful knowledge – or so I hope – and therefore I sat up and took notice. Perhaps, with the SDUK, I was staring a distant ancestor in the face? My genealogical interest was piqued.

The begats aren’t all that complicated. On this side of the Atlantic, the SDUK with the help of Josiah Holbrook spawned the Lyceum Movement in the same year as its debut in England. Lyceums, public lecture series, soon found purchase in major cities around the country. In the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, founded in 1829, I recognized the family resemblance I was looking for.

Although originally created for the betterment of young men for whom “the mind is active and the passions are urgent,” with the first presentations “given to those engaged in Trade and Commerce,” a calendar of lectures shows that the Boston SDUK wasted little time in expanding their program to include topics such as The Theory of Morals, Natural Philosophy, Shakespeare, and Astronomy. Hieroglyphics was on the agenda in 1833, about the same time that fascination with Ancient Egypt was capturing the imagination of many people in the region, notably Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism. From the standpoint of a 19th century American public eager to learn, useful knowledge had as much to do with profound questions as with practical ones. The same is true today.

Counted among the Boston speakers were eminent thinkers of the age, including Horace Mann and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Emerson’s fellow Transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau, although he did not speak before the organization, refers to the SDUK in his 1862 essay Walking and suggests an “equal need of a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Ignorance.”) In a lecture in 1842 physician and poet, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., turned a skeptical eye on Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions. It is remarkable both that Holmes’ spot-on analysis has survived the test of time so well – we could feature it as a talk today – and that homeopathy as a purported medical practice has survived 170 years of similar withering criticism.

The genealogical trail I was looking for itself becomes somewhat diffuse with the demise of the Boston SDUK in 1847. It reemerges clearly with the first Café Scientifique, organized by Duncan Dallas in 1998 in Leeds. This kind of grassroots public science forum is our group’s immediate forebear. As far as I have been able tell, the thirst for useful knowledge remains entirely unquenched. In addition, the capabilities of the Internet and particular social media now offer powerful tools for reaching out to an inquisitive public. I believe that a new Lyceum Movement is at hand. Long live the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge!

Marc Merlin is the Director of the Atlanta Science Tavern. When Marc isn’t busy diffusing useful knowledge he can be found biking around around Atlanta wearing a yellow jacket and a yellow helmet. He posts now and then on his own blog, Thoughts Arise .