Holly Tucker's Blog, page 79

August 6, 2012

Treating Snake Bite in Antiquity

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

(Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Pliny the Elder claimed there was an antidote for every snake venom, except cobra. Aelian agreed that the victim of cobra bite was “beyond help.” Some ancient antidotes, such as rue, myrrh, tannin, and curdled milk, were at least harmless; others were dangerous, and still others downright silly, such as boiled frogs, dried weasel, and hippopotamus testicle.

It was well known that natives of lands with venomous creatures such as snakes or scorpions often developed some immunity to the toxins. Some people’s resistance was so powerful that their breath or saliva was supposed to cure snake bites. According to the Romans, the Psylli of North Africa were so habituated to snake bite that their spit was an effective antivenin. Antivenin is derived from antibodies to live snake venom, and the implication was that Psylli immunity was achieved by an antiserum principle. Psylli saliva was eagerly sought by Romans during Cato’s Civil War campaigns in North Africa (first century BC). Lucan described the “unspeakable horrors” of viper bites until some Psylli joined Cato’s army to treat the constant stream of bitten soldiers. Lucan claimed the Psylli could identify the species of snake by the taste of the venom. The Psylli encouraged the notion of special immunity to boost their monopoly on curing envenomed wounds. Psylli practitioners soon set up shop in Rome, selling snake venoms and antidotes.

The best-known ancient remedy for snake bite was to suck out the venom by mouth. But this technique could be hazardous. The death of a snake-handler in Rome in 88 BC demonstrates the peril. Bitten by one of his cobras, he sucked out the poison himself. Aelian reported the fatal result: the venom “reduced his gums and mouth to putrescence” and spread through his body. Two days later he was dead. To avoid just such an accident, Trojan doctors used leeches, while Indian doctors stuffed a wad of linen in their mouths as a filter. The Roman physician Celsus recommended using a suction cup.

The reputation of Psylli saliva for neutralizing serpent venom was probably a misunderstanding by observers who saw a Psylli healer sucking out venom, noted Celsus. Their skill actually came from “boldness confirmed by experience.” Celsus pointed out that anyone “who follows the example of the Psylli and sucks out a wound will be safe,” provided that “he has no sore place on his gums, palate, or mouth.”

Indeed, snake venom can be digested safely, as long as no internal abrasions allow it to enter the bloodstream. This year, 13,000 soldiers from 20 nations in the US Marines’ jungle training course “Cobra Gold 2012” in Thailand drank cobra blood, a safe ritual that bestows confidence if not full immunity.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009) and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

August 3, 2012

Meet Helen King (Contributor Q&A)

As you may have seen, we’ve been adding some amazing contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them. This time around, we’re hearing from the amazing Helen King, Queen of the Traveling Vulva!

As you may have seen, we’ve been adding some amazing contributors to Wonders & Marvels. We want you to get to know each of them. This time around, we’re hearing from the amazing Helen King, Queen of the Traveling Vulva!

Here’s a sampling of Helen’s W&M posts. Some of my favorites include:

Midwives and Murderers in 17th Century London

Holly Tucker: Hi Helen. So glad to have you on the W&M and it’s great that we’ve actually met now at the ‘Retelling Familiar Tales of Pregnancy and Childbirth’ conference you co-organised! Could you tell readers a little bit about yourself?

Helen King: It’s great to be here! I am Professor of Classical Studies at the Open University. The OU was founded about 40 years ago and it’s genuinely ‘open’ – anyone can enrol with us, regardless of their qualifications, or lack of them. We offer supported distance learning, meaning that you use coursebooks, CDs, DVDs, online materials and also a personal relationship with your own tutor, possible face-to-face, possibly by email, phone and skype, depending on what works for you. There are all sorts of ways in, for example through ‘Openings’, http://www8.open.ac.uk/study/explained/study-explained/our-range-courses/openings-courses&samsredir=1342107829 which allow people new to study to try it out. I think that W&M is about a similar sort of openness.

HT: When did you know that you wanted to be a historian–and a historian of medicine to boot?

HK: I’ve always been obsessed with the ancient world, and I blame my parents for calling me ‘Helen’. I grew up on the stories of Helen of Troy. My first degree was in ancient history and social anthropology. I liked the idea of approaching the Greeks and Romans through social anthropology even though the traditional methodology of social anthropology – participant observation, living with the people you are studying – is unfortunately not really an option! I moved sideways into history of medicine because my PhD was on ancient Greek menstruation. And then I moved forwards into the Renaissance and later historical eras because I wanted to find out how people thought about ancient medicine before such modern things as the circulation of the blood, and antibiotics, and X-rays.

HT: I usually pick topics not because I know much about them, but because I know that I want to learn more. What areas still mystify you when it comes to the history of medicine? What do you want most to learn?

HK: I want to know a lot more about what happens when an idea that you really believe in – for example, that bloodletting is good for you – meets a new idea – like the circulation of the blood. How do people – patients – actually feel, at the time when ideas don’t quite add up? And how do patients and physicians arrive at a diagnosis – how much is about asking leading questions, how much is about observation? I’ve also been doing some work recently on art history, an area to which I am a complete newcomer. I was involved with a recent Leonardo da Vinci exhibition and have also recorded a podcast on Titian. Reading paintings is not like reading texts but I love trying it!

HT: OK, so here’s the question I always ask: If you could spend one day in the past, what day would it be? Why?

HK: Very difficult question! There are so many tantalising possibilities, but one would certainly be the day Alexander the Great died. I don’t really like retrospective diagnosis – if we have a description of a patient’s symptoms, does it actually help if we give them a modern label? – but I would like to know what happened to him. I grew up on Mary Renault’s novels about Alexander (my favourite is ‘The Persian Boy’) and I have to admit to a combination of hero-worship and desire where Alexander is concerned! What a guy – flawed, OK, but what a guy. Maybe I could have saved him…

Helen King was trained at University College London and has held posts at Cambridge, Newcastle, Liverpool and Reading before taking up her current position at the Open University. She has worked with a number of funding committees at the Wellcome Trust and the AHRC. In her spare time, she is a licensed lay preacher in the Church of England and a street pastor. She rather doubts whether the Church of England knows about her work on the history of therapeutic masturbation.

July 31, 2012

Women Speaking from the Archives

On a trip to the archives back in 2009, after a day of wallowing in dust, I made an exciting discovery: a documented moment of women’s speech in masque.

Masque—which became popular during the 17th century—allowed women to dance on stage as long as they remained silent. For years, scholars have argued a separation between women masquers (who were silent) and male actors (who could speak). But the Entertainment at Theobalds troubles these categories by asking what counts as on-stage speech. Must lines be scripted? Can they be impromptu? What if they result from intoxication?

Though masques were formal events, they were also extremely decadent. In 1606, when Queen Anna’s brother Christian IV of Denmark visited England, debauchery was the entertainment du jour. According to attendee John Harrington, “the Danes brought with them their habitual propensity for drinking, and James and his Courtiers complimented the strangers by partaking” (Nichols n.1). Not only were men involved; for the “Ladies abandon[ed] their sobriety, and [were also] seen to roll about in intoxication” (72).

By the start of the Entertainment at Theobalds, Danish liquor had saturated the court. King Christian, interrupted the performance, slurring a request to dance with the lady playing the Queen of Sheba; he then “fell down,” while fellow courtiers “went backward […] from wine” (Nichols 73). Describing the female masquers, Harrington says:

Now did appear, in rich dress, Hope, Faith, and Charity; Hope did assay to speak, but wine rendered her endeavors so feeble that she withdrew, and hoped the King would excuse her brevity […] Charity came to the King’s feet […] but said she would return home again, as there was no gift which Heaven had not already given his Majesty. She returned to Hope and Faith, who were both sick and spewing. (Nichols 73)

Adding to the melee, Peace “rudely made war with her olive branch,” beating her companions’ heads, while Victory committed “much lamentable utterance” (Nichols 73). Thus the masquing women literally spoke—repetitively and freely.

The Entertainment at Theobalds is the earliest recorded instance of women speaking in masque. It was a thrill to find because it encourages a reconsideration of women’s performance history.

Other W&M articles by Miranda Nesler:

Silence and the Scold’s Bridle

Charles I and the Act of Dying

Miranda Nesler is an assistant professor of early modern literature at Ball State University in Indiana. Her current book project, Disruptive Compliance: Silent Women in Stuart Drama examines how Renaissance women strategically used household entertainment to represent themselves as dramatic authors. She is also the editor at Performing Humanity in the Renaissance.

Citations:

Image: Inigo Jones. Costume Design, “The Masque of Augures.” London, 1622. (The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth House, Derbyshire)

John Nichols. The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James I, and His Royal Consort, Family, and Court, Collected from Original Manuscripts. Vol. II. London: Society of Antiquaries, 1828.

July 30, 2012

A Modern Exercise in Making an Old Herbal Remedy

By Lisa Smith

Earlier this month, I attended the newly revived Fairlop Fair, lured by the promise of dogs in silly costumes, bearded ladies, and Georgian medicine. My companions were leery of attending a medical herbalist’s workshop on eighteenth-century remedies, but the ominous clouds decided us: the workshop was undercover. I have studied early modern recipes for years, but this was my first attempt at making one.

To a modern person, old recipes are tricky to follow. Directions are frustratingly imprecise, while specific ingredients and tools are difficult to find or unsafe. There were also multiple recipes for the same remedy. Two recipes for Oil of St. John’s Wort from the popular collections of John Pechey (The London Dispensatory, 1694) and W.M. (The Queen’s Closet Opened, 1710) illustrate some of the possible differences. Pechey recommended infusing white wine, herb, and olive oil for three days in the sun. After repeating three times, the wine needed to be boiled, the mixture strained, and turpentine and saffron added. Then, one last boil.

Queen’s Closet suggested leaving a stopped glass with oil, white wine, herb, and oil of turpentine in the sun for ten days before boiling it ten to twelve hours. Next, the oil should be strained and more herb added. Another ten days in the sun and “this oil will then be of a deep red Colour, and will last seven years”. Both oils, nonetheless, treated similar problems: aches, bruises, sore limbs and joints, sprains.

But the recipe for Oil of St. John’s Wort shown to us by the medical herbalist appeared simple. We each took a couple handfuls of the herb, then stripped flowers and leaves and chopped them before jamming them into a small jar. Over that, we poured olive oil until it covered everything. The next bit needed to be done at home–putting the jar in the garden for three weeks. With the heat of the sun, it should turn brilliant red* and could be mixed into a base cream as an ointment for (surprise!) sore joints and wounds.

The exercise of making the remedy, however, highlighted problems in the timing, storage, and preparation of household remedies that I hadn’t considered. Steeping outside in the sun for three weeks sounds straightforward, but in London, we had grim weather between 7-20 July. We also regularly get foxes in the garden, leaving the jar vulnerable to curious and messy scavengers.** I kept the jar on our fox-free and sun-trapping kitchen windowsill instead. Most early modern recipes don’t specify precautions for keeping the jar outside.

A fox in our garden. Credit: M. Gudgeon, 2011©.

‘Handful’, moreover, was a common old measurement, but what does it measure exactly? We were told to take a couple handfuls of the eighteen-inch long stalks of herbs, but that provided only a handful of stripped leaves and flowers. Either way, it doesn’t sound like much until you physically handle the herb and realise that it takes a large quantity to produce a small jar. And St. John’s Wort was also a common ingredient in other remedies. Households, even with good-sized herb and kitchen gardens, would have needed to supplement their supplies by intensive gathering or purchase.

Academic historians can be a bit sniffy about historical reconstruction–but that is potentially a great loss. Of course we’ll never be able to recreate the production of early modern recipes exactly, but in the process of trying, we might actually learn something useful.

Now, to try my hand at some more easy recipes…

*Still waiting.

**Perhaps I should have persuaded my husband to urinate in an area around the jar, an old (and effective) animal-deterrent.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

July 29, 2012

Wonders & Links

3-5. Just told dispatcher will call in next hour. Really? . “@ComcastMichael: @history_geek when was this appointment scheduled for?” #

“@stevenbjohnson: join our research tools Skype convo coming up? @RebeccaSkloot @marynmck @David_Dobbs @sethmnookin #

Wonders & Links: The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence http://t.co/abNodDen #

“@RebeccaSkloot: @marynmck even the mere mention of deadly Dropbox/DT error sends chills. How to avoid? @David_Dobbs #

The display only. So much space! RT @marynmck: do you mean iMac or monitor-only? (i have 27" iMac) @daviddobbs @RebeccaSkloot #

Yep, deal-killer here too. RT @rebeccaskloot: No Pages 4 me… wasn't reliably compatible w docs w heavy track changes from multi users #

While we're talking Macs, does anyone use Pages instead of Word? How is that working for you? #

Macbook Air. How's speed? Keyboard on small one? anything I need to deck it out w/? (love how IT guy gave me permission to get 2nd comp!) #

Love the alliteration on this tweet. RT @boingboing: Thief stuffs Pomeranian puppy down pants http://t.co/oiA0KmO3 #

So Macbook Air, here I come. thoughts on whether I should get smaller or larger one? (will be computer I lug to office + research trips) #

IT person at university chastised me for being so cavalier with my computer. Says I need to get a backup computer. Well, yes, yes, I will! #

RT @performhumanity: @history_geek When did Continent shift to Gregorian calendar? Why? #urgentpaleographyqueries #

The "woosh" sound in Mountain Lion has to be coming from Mail. Have checked every place to turn it off. Driving me NUTS! #

Jealous!Pics? RT @performhumanity: Thought of you yesterday during our ink/quill making lesson yesterday. Must discuss. #materialculturenerd #

I think Ph.D.s are are secretly sadistic.

RT @drrubidium: EXAM DAY!!! Oh wait, I'm the one giving the the exam. #bwahahahahahahahaha #

RT @drrubidium: EXAM DAY!!! Oh wait, I'm the one giving the the exam. #bwahahahahahahahaha #Does Mac Calendar allow you to send out an email with all of the events for the day like Google does? #

one more tech question: Can't seem to turn of a "whoosh" sound in Mountain Lion since downloading. Don't know where it's coming from. #

Faculty job: HIstory of Sport and Society in US (UW-Madison) http://t.co/oECV1n0Q #

Not fair! RT @cplong: I'm at Monastero di Sant'Ubaldo (Gubbio, Umbria) http://t.co/Mdsj4ByV #

Throw some @devonthink in there,you'll rule the world! RT@sandra_gulland:Thanks, @history_geek ! I'm setting up new SnapScanS1300 right now. #

Noooo! Noooo! RT @thepinakes: @history_geek Click and clack are driving off into the sunset. #

Ending?! RT @kategardiner: With Car Talk ending, public radio ponders the future #pubmedia http://t.co/pN4GFMoH #

iPhone tips in France? Any prepaid SIM schemes you recommend? Need data and cheap international rates. (Loved @02 international in UK) #

Downloading Mountain Lion for Mac. Taking forever. Is this typical?? #

At Freshman Orientation, Helping Mom and Dad Let Go – http://t.co/hrV6KYm2 http://t.co/a0Tu8nIu #

Civil War Mourning Customs, by @karenabbott. Fascinating read! http://t.co/wJaSMOQh #

RT @comcastbill: have someone call me on home phone? Will DM #.40 min and sitting on hold to set up service w/@attcustomercare is ridiculous #

Fascinating. RT @bermaninstitute: How To Manipulate People Into Saying 'Yes' http://t.co/iRs51Aem Via @nprnews: #Neuroethics #

Civil War Mourning Customs by @karenabbott http://t.co/vI98j3FG #

Nine Books Not To Read on the Beach. http://t.co/vvvE4T86 #

What 40 Years Have Wrought: The Earth Since 1972 http://t.co/HQq6nWiK #

Can You Hear Me Now? Sound Technology of the 19th Century http://t.co/urn50Z3r @jenlucpiquant #

Civil War Mourning Customs: Karen Abbott (SIN IN THE SECOND CITY; AMERICAN ROSE) joins Wonders & Marvels. http://t.co/11Xvqrb7 #

Wonders & Links: Civil War Mourning Customs http://t.co/mMY4xMWi #

History of Tobacco Multimedia Collection at UCSF http://t.co/0QNxw6W7 #

Winston Churchill in his swimsuit, 1911/1922 http://t.co/khtXTDtk #

BBC_Future: Twitter to be 'official narrator' for #London2012 Olympics under NBC deal: http://t.co/aEgvDetM http://t.co/nukUm0ms #

Makes sense! Rethinking Labels Boosts Creativity http://t.co/IxvAoP1M @sciam #

RT @boraz: Oxford coma = what happens when an editor sees a manuscript without the Oxford comma and faints. #

very.

RT @davidherrold: Do you think Stevie Wonder is still superstitious? #

RT @davidherrold: Do you think Stevie Wonder is still superstitious? #RT @alokjha: From the Guardian: Craig Venter on the science of synthetic biology http://t.co/Wo8Pog60 #

China, as seen from European eyes, 17th century http://t.co/KGnnwoKg #

Artificial jellyfish built from rat cells http://t.co/PQrSmi8i edyong209 #

Wonders & Links: Bull Run, a Mars Landing and History as a Spectator Sport http://t.co/QL04iGK2 #

Powered by Twitter Tools

July 27, 2012

The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence

It is interesting to reflect on the drama that surrounded the decision to assert national sovereignty. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee proffered the initial resolution for independence to the Continental Congress. No immediate consensus emerged on its passage.

Debate on Lee’s resolution only began in earnest on July 1, with some members of congress still hoping to reconcile with the monarchy. A clear split occurred: New Hampshire, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia voted for independence. South Carolina and Pennsylvania cast votes against it, Delaware’s two delegates were divided, and the New York delegates declared they were ready to vote for the resolution but believed their instructions forbade them from doing so.

The next day, a momentous change took place. An additional delegate for Delaware, Caesar Rodney, who had been riding on horseback all night in the rain, arrived to break the tie, voting for independence. In his diary, future president John Adams describes Rodney as “the oddest-looking man in the world; he is tall, thin, and slender as a reed, pale; his face not bigger than a large apple, yet there is a sense of fire, spirit, wit, and humor in his countenance.” This unusual looking fellow is reputed to have ridden a remarkable eighty miles, changing horses along the way, entering Independence Hall in his boots and spurs, still dusty, shortly before the doors of Congress had been shut at the opening of the day’s session. Members of the South Carolina delegation had come to a consensus to vote for Lee’s motion. Pennsylvania had nine members who were seated in 1775, but only seven of them were present in the hall on July 2. Two of them were no longer active in Congress. One of those two, Andrew Allen, had left in June and would become a British Loyalist. The other was on his deathbed. The “yea” vote for Pennsylvania was cast by only three of the delegates who were present, with two others voting against it. John Dickinson and Robert Morris were in the hall but abstained from voting, allowing the affirmative vote to stand. That left New York’s delegation. But it did not vote either way, only adding its support several days later. Congress had now resolved,

That these United Colonies are, and, of right, ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connexion between them, and the state of Great Britain, is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

That was the actual declaration of independence, which was adopted on July 2. The document that has come to be known by that name, the Declaration of Independence, was an explanation of congress’s decision to absolve its allegiance to England and the nation’s principles.

Alexander Tsesis teaches at Loyola University, School of Law-Chicago. He is author of For Liberty and Equality: The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence (Oxford University Press).

July 23, 2012

Civil War Mourning Customs

By Karen Abbott (W&M contributor)

By Karen Abbott (W&M contributor)

Nearly 700,000 men died in the Civil War, more from disease than from battlefield wounds (“bowels are of more consequence than brains” was a common jest”) and these fatalities ultimately belonged to those left behind; it was the survivors who had to contend with the business of burying and grieving. The scale of the carnage demanded a strict set of social rituals, a culture of mourning in which the literal embodiment of death was considered the best way to accept it.

For women this meant stocking their armoires with “mourning” fashion, which was more readily available in the North even though its death rate was one third of that of the Confederacy. In the spring of 1863, down on Ladies’ Mile, Lord & Taylor opened a “mourning store” where new widows could dress their grief fashionably, selecting from a variety of now-esoteric fabrics: Black Crape Grenadines, Black Balzerines, Black Baryadere Bareges, Black Bareges, Mourning Silks, Lawns, Chintzes, Alpacas, Barege

Shawls, and Grenadine Veils. Godey’s Lady’s Book, the mid-19th century’s answer to Vogue, regularly printed drawings of bonnets, collars, sleeves, breakfast caps and a variety of mourning dresses for all occasions.

Mourning attire evolved over a period of stages, growing progressively less stringent. “Deep” or “heavy” mourning required a widow to wear all black dress and accessories, including a heavy black crepe veil. Jewelry was verboten unless it was made of polished coal, a lock of hair of the deceased, or a small picture of the deceased. Next came full mourning, during which her black dress and veil could be accented by lighter shades of lace and cuffs. The final stage, half mourning, allowed shades of lavender and gray; Godey’s recommended a black silk and French grenadine ensemble topped off with a Leghorn hat, trimmed with black velvet and black plume.

Mourning attire evolved over a period of stages, growing progressively less stringent. “Deep” or “heavy” mourning required a widow to wear all black dress and accessories, including a heavy black crepe veil. Jewelry was verboten unless it was made of polished coal, a lock of hair of the deceased, or a small picture of the deceased. Next came full mourning, during which her black dress and veil could be accented by lighter shades of lace and cuffs. The final stage, half mourning, allowed shades of lavender and gray; Godey’s recommended a black silk and French grenadine ensemble topped off with a Leghorn hat, trimmed with black velvet and black plume.

For a widow, the entire public grieving process lasted a minimum of two and a half years, although after April 1865 Mary Todd Lincoln spent the rest of her days swaddled in black. She was too distraught to appear at her husband’s funeral but later recorded her grief in a private letter to a friend: “Time brings so little consolation to me and do you wonder when you remember whose loss. I mourn over that of my worshipped husband, in whose devoted love, I was so blessed, and from whom I was so cruelly torn. The hope of our reunion in a happier world than this, has alone supported me, during the last four weary years.” When she died in Springfield in 1882, her body was laid out in the parlor of her sister’s home—in the exact spot where, 40 years before, she had stood as a bride.

Karen Abbott is the author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose, both New York Times bestsellers. She is a featured contributor to Smithsonian magazine’s history blog, Past Imperfect, and also writes for Disunion, the acclaimed New York Times series about the Civil War. She’s at work on her next book, a true story of four Civil War spies who risked everything for their cause. Find her online at www.karenabbott.net or @KarenAbbott on twitter.

References:

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Dorothy Denneen Volo and James M. Volo. Daily Life in Civil War America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998.

“Sealed With Sorrow.” New York Times, September 9, 1999.

Images:

Young girl mourning her cavalry father (Library of Congress)

Woman in mourning dress and jewelry (Library of Congress)

July 22, 2012

Bull Run, a Mars Landing and History as a Spectator Sport

By Marc Merlin (Atlanta Science Tavern contributor)

As the Director of the Atlanta Science Tavern my assignment at Wonders & Marvels is to work with members of my group and arrange for one of us or one of our speakers to submit a blog post each month, our charter from Holly Tucker being, “history with a scientific slant.” This time around I take take another turn at bat and in doing so take the liberty to expand the charter a bit to include, “making history with a scientific slant.”

First Battle of Bull Run (Kurz & Allison)

You see, in exactly two weeks, if our promotional efforts pay off, a couple hundred of people will assemble at Georgia Tech’s Centergy building to await and to celebrate the landing of the remarkable new Curiosity rover on the surface of Mars. We are moved to come together for this occasion by our shared fascination with science and with the planets. In addition, the symposium we have planned and late-night party that will follow also offer us an opportunity to be a part of a moment in scientific history.

History as a spectator sport is, of course, nothing new. Notably, 151 years ago almost to this very day, the mid-19th-century media buzz surrounding the impending First Battle of Bull Run propelled hundreds Washington common folk, socialites and members of the political elite to Centreville, Virginia to watch the first major military engagement of the American Civil War. Not only were their expectations of an easy victory dashed, but the resulting rout of the Union Army, their champions, enveloped the spectators themselves, transforming them into a panicked, fleeing mob. The spectacle and donnybrook of what the Confederates called First Manassas is wonderfully recounted in John J. Hennessy’s essay War Watchers at Bull Run During America’s Civil War.

[image error]

“Seven Minutes of Terror” NASA Video

Suffice it to say, we won’t be at any personal risk waiting word from the Red Planet 160 million miles away, but our champion, Curiosity, will have to survive what has been described quite justifiably as “seven minutes of terror” to reach her destination. Let us hope that she prevails in her battle with the forces of the Martian atmosphere during her fiery descent and that all her painstakingly practiced maneuvers come off without a hitch, all resulting in a gentle touchdown in Gale Crater where she will embark on the exploration of a nearby mountain searching for the precursors of life on that marvelous other world.

And, if all goes well, at about 1:30 am in Atlanta on the morning of Monday, August 6, our room will fill with cheers and shouts among those of us who have turned out (and endured) and, satisfied to have been a part of history in the making, we will all go marching home to catch up on much needed sleep. Hurrah!

You can join Marc Merlin and the Atlanta Science Tavern for their symposium and celebration by visiting their Mars Landing Party website the night of Sunday, August 5 and clicking on the live video stream. Your safety is guaranteed.

July 20, 2012

I Need Your Help—Again!

Last month I asked readers of this blog what irritated them when reading historical fiction, to help me prepare for a talk on “The Ten Commandments of Writing Historical Fiction.” I got some great responses, especially Vrmarvin’s dislike of “the over abundance of language describing costuming. Really, does it matter what color they were wearing? When you read contemporary accounts of historical events, clothing is rarely mentioned until it is important to the event being described. There’s no reason that authors of historical fiction should belabor every ruffle or flounce”—which I plan to expand to include overdescription in general. True, it’s necessary to set the stage, especially when the reader is unfamiliar with the world being depicted, but really, do we need passages such as the “torphut” excerpt I quoted in yet another post?

(Vrmarvin, please write to TracyTBarrett [at] yahoo [dot] com to arrange my sending you a book.)

I recently presented a version of that “Ten Commandments” talk to a group of school librarians, one of whom asked me a question I couldn’t answer, so once again I’m asking for your help.

I had just discussed the “commandment” that recommends, “Thou shalt not repeat falsehoods.” Don’t rely on common knowledge; verify, verify, verify. That’s when I got the question: You can’t check out every detail, so how do you know what piece of received wisdom is true and which is iffy and must be verified? You can’t look up everything, after all.

The best I could do was to tell them that my rule of thumb is the more appealing the story, the more I have to check it out. A “fact” that is both false and boring disappears quickly. If it’s false and interesting, it has a chance of sticking around, and people come to believe it. You see this a lot in spurious word origins: it’s false that “butterfly” used to be “flutterby,” that “posh” stands for “port out, starboard, home,” that “cop” comes from “constable on patrol,” etc.

The problem is that there are lots of facts that are both true and interesting!

So my question for you, whether readers, writers, or both: What raises your antennae? What kind of historical detail makes you suspicious enough that you feel the need to verify it?

July 18, 2012

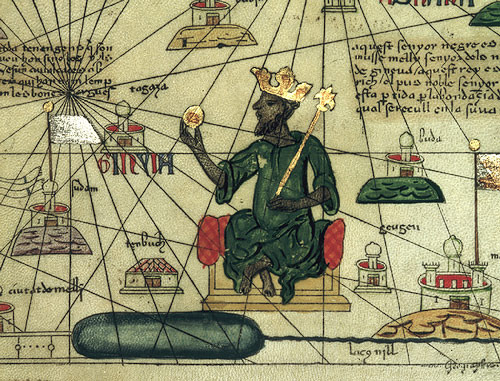

From Here to Timbuktu

By Pamela Toler

Timbuktu has been in the news lately as a result of growing control by Islamic extremists, whose narrow interpretation of sharia law has led to the destruction of Muslim tombs, innocent people lashed in the streets, and thousands of refugees fleeing their homes.

It’s a good time to remind people of a time when Timbuktu was celebrated as a center of learning and wealth.

Founded in the eleventh century at the point where the Niger River flows northward into the Sahara, Timbuktu was perfectly located to become a trading center between the Islamic states of north and west Africa. Caravans traveled south across the Sahara carrying silks from Persia, steel from Damascus, and, most precious of all, books; the caravans traveled north again laden with gold, ivory, and salt.

Over time, the city attracted not only merchants, but scholars. By the fourteenth century, Timbuktu wasn’t just importing books but creating them. The city was home to a vibrant book copying industry. Commentaries written by the scholars of Timbuktu were read in Cairo and Mecca. Timbuktu was a college town, with three universities and 180 Quranic schools. Students traveled from all over the Islamic world to study there, often making up a quarter of the city’s population.

Timbuktu entered the European imagination in 1324, when the city’s ruler Mansa Musa went on pilgrimage to Mecca. The West African king was a big spender, with an apparently inexhaustible supply of gold. So much that the precious metal’s value dropped in every city he passed through. (Contemporary estimates for how much gold he carried with him ranged from one hundred camels carrying gold to a thousand camels carrying one hundred pounds of gold apiece.) He built a mosque everywhere that he stopped for the Friday prayers. He paid for every service in gold and gave lavish gifts to his hosts. Beggars lined the streets when he passed in the hope of catching gold nuggets that meant they would never have to beg again.

Not surprisingly, Mansa Musa’s princely display of wealth caught the attention of the Venetian and Genoese merchants resident in Alexandria. They quickly sent word home about the king of Mali and his golden capital of Timbuktu. Soon trading firms from Granada, Genoa, Venice and the Flemish markets of the north established posts in North African towns like Marrakech and Fez, hoping to trade European manufactured goods for Saharan gold.

European merchants trading with Timbuktu through North African middleman, but never saw the city itself. In fact, the first European traveler did not arrive in Timbuktu until 1828, several hundred years after its glory days. Timbuktu became short hand in the west for “really, really far away”–a distant place at the edge of civilization.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.