Holly Tucker's Blog, page 83

April 15, 2012

Q&A with Deblina Chakraborty and Sarah Dowdey

Do you know about STUFF YOU MISSED IN HISTORY CLASS? If not, you need to! It’s free via their website or via iTunes.

I had a chance to interview Deblina Chakraborty and Sarah Dowdey about their fantastic podcasts.

HT: As you know, I’m a big fan of your history podcasts. The two of you keep me company nearly every morning while I’m on the treadmill. Could you tell me more about how the show first came together and a sense of who your listeners are?

SD: The podcast started back in 2008 as a way to repurpose all the history articles being written at the time at HowStuffWorks.com. Since then, it’s changed titles, formats and hosts. I joined the show in 2009 and paired up with Deblina the next year. Our listeners are a diverse group! We hear from history professionals and students, of course, but also from enthusiastic history buffs of all ages. There’s a large international listenership made up of Peace Corps volunteers, military, people who are interested in hearing a different take on their own country’s history, and folks who listen to practice their English. Most are probably a bit like you, though: They like to listen while they run, drive, or work.

HT: Sarah, I can tell in the podcasts that you’re a Francophile. (Who else would do an entire series on the Bourbon kings!) Tell me more about your French interests.

SD: Funny enough, Deblina actually kicked off the Bourbon series due to a fascination with Henri IV’s recently identified head. But I do love covering French history, probably for a similar reason — it seems to combine glamour with unrest, fashion with the macabre. There’s an appealing contradiction that interests me and engages different types of listeners — people who love queens and missing jewels, as well as those who love poisons and missing heads.

Holly Tucker: Deblina, what are you most fascinated by?

Deblina Chakraborty: I’m fascinated by so many things — it’s probably no secret that I have a thing for spies and true crime stories. Lately, though, I can’t seem to get enough of science-related history. That probably stems from the fact that I come from a family of science nerds, and that the stories are often so deliciously unexpected. We tend to think of science as this really rational, empirical subject, but its history is often filled with mystery, intrigue and adventure, as well as characters who are passionate, quirky and at the end of the day, devastatingly human.

HT: If you had to pick your favorite episode or series of episodes, which would it be? And why?

Sarah Dowdey: My favorite episodes are the ones where I got completely caught up in the research process. ”The Shipwreck that Saved Jamestown” is an old-time favorite: a harrowing shipwreck, early American colonists, a Shakespeare connection, and money with wild pigs on it! More recently, I really enjoyed putting together “The Rite of Spring Riot.” It was all about one night — the 1913 premiere of the ballet — but it featured three different biographies and a whole lot of background on the Ballets Russes. Plus, how often do you get to insert a bassoon clip into a podcast?

DC: One of the first episodes I researched — “Who was the real Sherlock Holmes?” — is still one of my favorites, probably because I love uncovering the real stories behind fictional characters and events (which are often even more fascinating than the works they inspired). I also got a bit of a research high while putting together “A Tale of False Dmitry,” a podcast about a 17th century Russian imposter. False Dmitry’s story of pretending to be the long-lost son of Ivan the Terrible and actually managing to usurp the Russian throne is so outrageous and implausible by today’s standards, it’s hard not to get hooked.

HT: I’m always so impressed by the research and preparation that has to go into every episode. How do you decide what to cover? And once you decide, how do you go about putting the show together?

SD: We draw very heavily from listener suggestions. Sometimes it’s just one person with a really compelling pitch; other times, there’s such a demand for a particular topic (Lizzie Borden!), we feel we have to cover it. We also draw on what we’re reading and watching, and we try to tie into anniversaries and things going on the world. To work, though, the topic has to be interesting to us — something we’ve realized really comes across in our research and even our voices. It also has to be accessible. We don’t have a research budget, so we rely on our public libraries and online sources (especially Galileo, with its subscriptions to databases like ProQuest and EBSCOhost). I think people are sometimes surprised by how quickly we choose a topic and start researching, but with two episodes a week, it’s important we don’t have too many false starts. Finally, a topic has to be contained. We can’t handle an episode like “How the Civil War Worked,” so we hone in on 20-minute stories, like “The Death of Stonewall Jackson.” Once we’ve picked a topic and gathered sources, we make a really detailed outline. That allows us to remember the names, dates and story arc we’re going for but still have some flexibility and room for tangents when we record with our producer Lizzy. After we’re done, we experience “podcast relief” and quickly get back to our day-to-day work: editing articles!

HT: So inquiring minds want to know…what’s on tap for upcoming shows? And how can readers get in touch with you for show ideas?

SD: Though they’re always ongoing, we’ll certainly crank up topics for Black History Month and Women’s History Month. To mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, we’ve already featured series on wartime spies, as well as Civil War doctors and nurses, so we’ll probably look for a new angle there. Listeners can find us on Twitter @MissedinHistory and on Facebook, or e-mail us at historypodcast@discovery.com.

Q&A with Deblina Chakravorty and Sarah Dowdey

Do you know about STUFF YOU MISSED IN HISTORY CLASS? If not, you need to! It’s free via their website or via iTunes.

I had a chance to interview Deblina Chakravorty and Sarah Dowdey about their fantastic podcasts.

HT: As you know, I’m a big fan of your history podcasts. The two of you keep me company nearly every morning while I’m on the treadmill. Could you tell me more about how the show first came together and a sense of who your listeners are?

SD: The podcast started back in 2008 as a way to repurpose all the history articles being written at the time at HowStuffWorks.com. Since then, it’s changed titles, formats and hosts. I joined the show in 2009 and paired up with Deblina the next year. Our listeners are a diverse group! We hear from history professionals and students, of course, but also from enthusiastic history buffs of all ages. There’s a large international listenership made up of Peace Corps volunteers, military, people who are interested in hearing a different take on their own country’s history, and folks who listen to practice their English. Most are probably a bit like you, though: They like to listen while they run, drive, or work.

HT: Sarah, I can tell in the podcasts that you’re a Francophile. (Who else would do an entire series on the Bourbon kings!) Tell me more about your French interests.

SD: Funny enough, Deblina actually kicked off the Bourbon series due to a fascination with Henri IV’s recently identified head. But I do love covering French history, probably for a similar reason — it seems to combine glamour with unrest, fashion with the macabre. There’s an appealing contradiction that interests me and engages different types of listeners — people who love queens and missing jewels, as well as those who love poisons and missing heads.

Holly Tucker: Deblina, what are you most fascinated by?

Deblina Chakraborty: I’m fascinated by so many things — it’s probably no secret that I have a thing for spies and true crime stories. Lately, though, I can’t seem to get enough of science-related history. That probably stems from the fact that I come from a family of science nerds, and that the stories are often so deliciously unexpected. We tend to think of science as this really rational, empirical subject, but its history is often filled with mystery, intrigue and adventure, as well as characters who are passionate, quirky and at the end of the day, devastatingly human.

HT: If you had to pick your favorite episode or series of episodes, which would it be? And why?

Sarah Dowdey: My favorite episodes are the ones where I got completely caught up in the research process. ”The Shipwreck that Saved Jamestown” is an old-time favorite: a harrowing shipwreck, early American colonists, a Shakespeare connection, and money with wild pigs on it! More recently, I really enjoyed putting together “The Rite of Spring Riot.” It was all about one night — the 1913 premiere of the ballet — but it featured three different biographies and a whole lot of background on the Ballets Russes. Plus, how often do you get to insert a bassoon clip into a podcast?

DC: One of the first episodes I researched — “Who was the real Sherlock Holmes?” — is still one of my favorites, probably because I love uncovering the real stories behind fictional characters and events (which are often even more fascinating than the works they inspired). I also got a bit of a research high while putting together “A Tale of False Dmitry,” a podcast about a 17th century Russian imposter. False Dmitry’s story of pretending to be the long-lost son of Ivan the Terrible and actually managing to usurp the Russian throne is so outrageous and implausible by today’s standards, it’s hard not to get hooked.

HT: I’m always so impressed by the research and preparation that has to go into every episode. How do you decide what to cover? And once you decide, how do you go about putting the show together?

SD: We draw very heavily from listener suggestions. Sometimes it’s just one person with a really compelling pitch; other times, there’s such a demand for a particular topic (Lizzie Borden!), we feel we have to cover it. We also draw on what we’re reading and watching, and we try to tie into anniversaries and things going on the world. To work, though, the topic has to be interesting to us — something we’ve realized really comes across in our research and even our voices. It also has to be accessible. We don’t have a research budget, so we rely on our public libraries and online sources (especially Galileo, with its subscriptions to databases like ProQuest and EBSCOhost). I think people are sometimes surprised by how quickly we choose a topic and start researching, but with two episodes a week, it’s important we don’t have too many false starts. Finally, a topic has to be contained. We can’t handle an episode like “How the Civil War Worked,” so we hone in on 20-minute stories, like “The Death of Stonewall Jackson.” Once we’ve picked a topic and gathered sources, we make a really detailed outline. That allows us to remember the names, dates and story arc we’re going for but still have some flexibility and room for tangents when we record with our producer Lizzy. After we’re done, we experience “podcast relief” and quickly get back to our day-to-day work: editing articles!

HT: So inquiring minds want to know…what’s on tap for upcoming shows? And how can readers get in touch with you for show ideas?

SD: Though they’re always ongoing, we’ll certainly crank up topics for Black History Month and Women’s History Month. To mark the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, we’ve already featured series on wartime spies, as well as Civil War doctors and nurses, so we’ll probably look for a new angle there. Listeners can find us on Twitter @MissedinHistory and on Facebook, or e-mail us at historypodcast@discovery.com.

April 14, 2012

Ruff-ing It and the Politics of Fashion

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (W&M Regular Contributor)

Writing in 1637, the Marquis of Careaga deplored the “delicate and womanly” fashions that enraptured Spanish men. He warned that these indulgences “overthrew their spirits, unnerved their determination, weakened their energy, and diminished their manly vigor.”

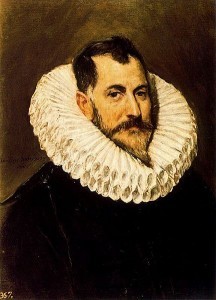

We might wonder what sort of fashions could inspire such vitriol. A particular item stood at the heart of his comments and those of other moralists: a ruff. Specifically, a Spanish variation on the ruff known as the cuello. The cuello, represented here in a portrait by El Greco, had become an object of excess.  This collar was several inches high, tinted with powders, and often decorated with fancy threads. And it had to be washed and starched daily to maintain its appearance. By the early seventeenth century, some tried to elevate their cuellos even further, using an undergirding support known as an alçacuello. Thus, the cuello came to embody a host of moralizing complaints that ranged from foreign policy to the economy to fears of compromised masculinity. To begin with, the dyes used to tint them were imported from Spain’s enemy, the Dutch. Many argued that the nobility’s ducados would benefit Spain more if they were spent locally. Finally, the cuello violated the prevailing code of virtuous virility that prized moderation, control, and a sense of effortlessness in matters of style. If anything, the cuello screamed excess and effort. Everyone knew how labor-intensive their care and presentation was. Men who indulged in this fashion were often characterized as effeminate. Their inability to dress with moderation compromised their masculinity. At a time when Spain was engaged in military conflict across the globe, the “manly vigor” of its male citizens had serious political consequences.

This collar was several inches high, tinted with powders, and often decorated with fancy threads. And it had to be washed and starched daily to maintain its appearance. By the early seventeenth century, some tried to elevate their cuellos even further, using an undergirding support known as an alçacuello. Thus, the cuello came to embody a host of moralizing complaints that ranged from foreign policy to the economy to fears of compromised masculinity. To begin with, the dyes used to tint them were imported from Spain’s enemy, the Dutch. Many argued that the nobility’s ducados would benefit Spain more if they were spent locally. Finally, the cuello violated the prevailing code of virtuous virility that prized moderation, control, and a sense of effortlessness in matters of style. If anything, the cuello screamed excess and effort. Everyone knew how labor-intensive their care and presentation was. Men who indulged in this fashion were often characterized as effeminate. Their inability to dress with moderation compromised their masculinity. At a time when Spain was engaged in military conflict across the globe, the “manly vigor” of its male citizens had serious political consequences.

The crown, in fact, vigorously legislated against them. As early as 1594 it forbid the adornment of cuellos, specified a particular width for them, and that any decorative elements be white. Again, in 1600 it issued orders regarding the width of cuellos. Yet the fashion endured.  Ultimately, rather than modify their appearance, the crown abolished them completely in 1623. It presented as an alternative the low, flat collar of the valona. Even the king himself was not above this new rule as we can see here in Velázquez’ portrait of Philip IV (1621-1665). Not unlike today, seventeenth-century fashion was intensely political.

Ultimately, rather than modify their appearance, the crown abolished them completely in 1623. It presented as an alternative the low, flat collar of the valona. Even the king himself was not above this new rule as we can see here in Velázquez’ portrait of Philip IV (1621-1665). Not unlike today, seventeenth-century fashion was intensely political.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

April 10, 2012

Contributor Q & A: Marri Lynn

Marri Lynn

As editor of Wonders & Marvels, I have the pleasure

of introducing our monthly regular contributors.

On the docket today is Marri Lynn…

Holly Tucker: Hi Marri. So glad to have you on the W&M. Could you tell readers a little bit about yourself?

Marri Lynn: I'm glad to be a part of W&M! I have an MA in medical history from McGill University, and I studied history at the University of Victoria for my BA just before that. Since receiving my MA, I've been studying French and working as the copy editor for the McGill Tribune. I unexpectedly fell in love with the city of Montreal while studying for my MA here, and so I'm prolonging the affair as long as possible, continuing to look for opportunities in this city sans pareil.

HT: When did you know that you wanted to be a historian–and a historian of medicine to boot?

ML: At the core, I'm driven by stories. It was actually research for a character for a fiction piece that led me to discover medical history. I became fascinated with the ways in which people understood (or sometimes did not understand) health. Health, and the struggle to understand and preserve it, is a core struggle throughout time, and it intersects in fascinating ways with other human dramas like religion, gender and sexuality, and science. I found myself encouraged in this direction by many wonderful mentors; before I knew it, I was writing my undergraduate honors thesis on nineteenth-century phlebotomy, delivering a lecture on Vesalius' use of mechanical metaphors at a symposium, and then boarding a plane for Washington, D.C., to study Byzantine spices-as-medicine for two weeks at the amazing Institute for the Preservation of Medical Traditions. (Link to their website.)

HT: I usually pick topics not because I know much about them, but because I know that I want to learn more. What areas still mystify you when it comes to the history of medicine? What do you want most to learn?

ML: Too many, and too much. One thing that I keep coming back to is medicine in the context of cultural exchanges, especially along Eastern-Western lines. The work of Shigehisa Kuriyama really opened my perception of these exchanges, after I read his article about the relationship between Chinese acupuncture and Western bloodletting while researching for my undergraduate thesis. (To read it, see: "Interpreting the History of Bloodletting," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50, 11-46 (1995).) I've also always been particularly interested in 'rangaku,' or Japan's reception of Dutch (and broadly Western) scientific and medical knowledge in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

HT: Now I always ask this of contributors, so bear with me: If you could spend one day in the past, what day would it be? Why?

I dreaded this question! And meditated (and anguished) far too long on it. Setting aside many tantalizing choices, I think I'd like to spend a day on the shores of Lake Geneva in 1816, during that summer when Lord Byron, Percy and Mary Shelley, and John Polidori hung out together and catalyzed the horror genre. Getting to meet these people both as individuals and as players within an (in)famous group dynamic would really be a treat, and the proverbial icing on the cake of a kind of personal and cultural imaginative indebtedness I've felt toward them since I was younger. It would answer a few historical questions and really electrify my own creativity in addition to being a great time.

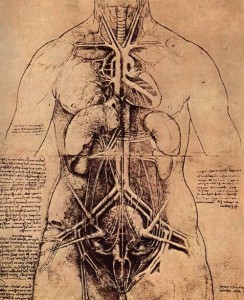

Imaginary body parts

Leonardo da Vinci, section through female body

I’ve been thinking a lot about imaginary body parts recently. The Queen’s Gallery is opening a new exhibition of the anatomical drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in May; put it on your ‘to do’ list if you are in London – http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/exh... - and I have done some work for the audio guide and the app (which means you can ‘see’ it even if you are not in London!). One of the amazing things about these pages from Leonardo’s notebooks is that many (to the non-anatomist) very convincing pictures were drawn from his imagination, before he had access to human body parts to dissect. In particular, a sketch of coitus shows him thinking about where everything goes – and includes imaginary channels from the womb to the breasts, based on the ancient belief that breast milk is made out of menstrual blood. His sketch of the penis has an extra channel for the soul to be transmitted through. His section of the female body includes parts from animals. His famous drawing of the foetus in the womb is based on a real foetus, but when he did it he had not seen the womb, so that was idealised as a sphere, and the drawings surrounding it are based on the placenta of a cow. And so on.

Leonardo’s drawings show us the early stages of what happened when the ideas about the body inherited from Greek and Roman medicine were challenged by the ‘real’ body. A later example is the work of William Harvey. Before Harvey, it was thought that blood made its way from one side of the heart to the other through ‘invisible holes’ in the septum that divides right from left. One of the preconditions for Harvey’s 1628 announcement of the circulation of the blood was the discovery of the pulmonary transit, the movement of blood from one side of the heart, to the lungs, and back again to the other side of the heart. But the pulmonary transit had been proposed much earlier, for example by Ibn al-Nafīs in the thirteenth century. Harvey’s work was based on a combination of speculation, based on his observations about the sheer quantity of blood in the body, and animal vivisection; that of Ibn al-Nafīs was pure speculation, based on the requirements of his thinking about the body in theological and philosophical terms. Harvey rejected the imaginary ‘invisible holes’, but for his theory of circulation to work he had to rely on something else that was invisible – the capillaries, which his theory of circulation needed as the route between the arterial system and the venous system. Harvey couldn’t see them, as microscopy was not quite sufficiently developed.

But while ‘invisible holes’ in the septum of the heart are Wrong, ‘invisible channels’ between arteries and veins are Right. So far!

April 8, 2012

The Remains of the Day

If I had the chance to choose one item to remain after my death, one artefact that would encapsulate my entire life and all its choices and decisions, I seriously doubt that I would choose anything that I either gave or received as a gift at my wedding.

If I had the chance to choose one item to remain after my death, one artefact that would encapsulate my entire life and all its choices and decisions, I seriously doubt that I would choose anything that I either gave or received as a gift at my wedding.

Believe me, nothing from that day would give any future biographers any tremendous insight into my true nature.

But why do physical artefacts matter so much at all? Why is it so important that we know so-and-so touched this, or wore that, or handled this very thing?

I don't know why it matters, but it does.

Even Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the most fascinating, powerful, and politically important historical figures a person could name, has only left us with one sparkly vase to remember her by.

And I bet she didn't even like it all that much.

It was a gift to her first husband, Louis VII; just a rather smallish rock crystal vase that her family prized. And Louis didn't exactly treasure it for the rest of his natural days. Pious and thickheaded as ever, Louis pretty much turned around and gave it to his pal Abbot Suger, who dedicated the thing, naturellement, to God.

The annoying idea of anyone's husband regifting a treasured wedding present directly to his closest male friend aside, it just kind of breaks my heart that this is the only actual, physical item that remains of Eleanor — the only thing we can be absolutely sure was handled or owned by her during her long, extraordinary life. Again, I don't know why this matters. But it does.

We don't even really know what she looked like.

Maybe this is why I usually deal with more recent history, having settled long ago on the 19th century as my own personal historical stomping grounds. After all, portraits abounded during my chosen time period, and they could even be reasonably relied on to convey not just a person's physical features but also at least some inkling of their true personality. By the 1840s, you've even got the beginnings of portrait photography, and the unbelievable ability to connect across the years by gazing into your subject's eyes.

It matters. At least, to me it does.

I enjoy Eleanor. I respect the pants off of her. I've always been fascinated by her story, her wide travels, her relationship with power at such an interesting and vital point in European (and church) history. But I don't love her, because I can't know her. Not really, not viscerally, intuitively. Not like I know my cast of characters from the 19th century, who when I stumble across them by surprise, fill me with a sense of companionable familiarity. Like old college friends I never lost touch with, or at the very least, never stopped thinking of.

I suppose that's why we history nuts choose our eras, as much as for any other reason. We find out, early on, whose story we can really connect with on a basic, human level. Whose secret thoughts, hidden motives, and galvanizing imperatives we can somehow grok, with an intuitive immediacy that makes their daily struggles, triumphs, faults, and heroisms real to us. Really real. Makes-you-cry-to-think-about-it real.

It's different for different people. I know plenty of people who can't get down with the Victorians in the slightest, but who have absolutely no problem whatever hanging out with the Romans, Etruscans, or Greeks. Folks who couldn't care less about the petty squabbles of early Colonial Americans, but whose hearts thrum in sympathy with the early Christians.

There is, literally, no accounting for taste. And not everyone seems to require the physicality of an artefact, a collection of letters, or a true likeness. What does it matter ift a person's eyes were blue, and brittle with hardship, or dark brown, and limpid with empathy?

Possessions and portraits. They shouldn't matter to me as much as they do, I guess. But there we are.

Would I be able to have long, late-night cozy chats with Eleanor if she'd left behind an extra brooch, a doodled-in bible, a pair of shoes, a rock solid portrait that brought her vividly to life? Maybe.

Maybe not, though.

In the end, I think our subjects choose us, airy fairy as that might sound. And Eleanor, quite simply, belongs to other folks. That's fine. She's got her fans. And I'm extremely glad they're around to tell her story to the rest of us.

You keep telling your stories. I'll keep telling mine.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady and studies old daguerrotypes and miniature portraits from the 19th century more than most people watch TV.

April 6, 2012

Who Made the First Fake Fossils?

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Paleontological hoaxes and fraudulent fossils are assumed to be modern phenomena. The earliest case is generally thought to be in 1725, when phony fossils carved by rivals ruined Johann Beringer's reputation. The notorious Piltdown Man fraud was perpetrated in 1913. Since the startling discovery of feathered dinosaur remains in China, very sophisticated bogus fossils have fooled amateurs and scientists. The most scandalous incident occurred in 1999 when National Geographic featured a "missing link" feathered dinosaur, later exposed as a cunning composite of real fossils. Fossil forgery has a long history in China. Well-preserved fossil fish impressions were so popular in twelfth-century China that numerous counterfeits were produced.

Fossil replicas were not always intended to defraud, however. Fossils gathered in antiquity, from large vertebrate bones to small shells, emerge from archaeological sites around the world. These discoveries are mute testimony to ancient people's interest in living organisms somehow transformed to stone. Such marvels were worked into decorations, placed in graves, or dedicated in temples—and sometimes they were duplicated for reasons not yet understood.

In Malta, islands south of Sicily, fossils attracted attention at a very early date. In the sixth century BC, the Greek philosopher Xenophanes observed marine shells embedded in Malta's bedrock and concluded that the islands had once been under the sea. According to the Roman statesman Cicero, Malta's great Temple of Juno was renowned for its treasure of ivory tusks of prodigious size (most likely Pleistocene mammoths). But evidence for Maltese fossil collecting goes back even further. As early as 3000 BC, heaps of fossil teeth from the gigantic Miocene shark Carcharodon megalodon were dedicated in sacred sites. By 2500-1500 BC, Maltese potters were using the serrated shark teeth to decorate clay bowls with parallel grooves. Much later, in the Middle Ages, Maltese shark teeth (glossopetrae, tongue stones) became such a sought-after miracle remedy in Europe that laws forbade faking them.

The Maltese had been manufacturing "fossils" for their own uses since the Neolithic period. As Xenophanes had noticed, helicoid gastropod fossils (screw-shaped shells) of are common. These small Miocene fossils turn up in vast numbers in the most archaic stone temples on Malt. But what really surprised the archaeologists were the oversized man-made replicas among the real fossils, some carved from limestone and others modeled in baked clay. The only other similar artifacts known from this era are gold and marble shark vertebrae discovered in Minoan sanctuaries on Crete.

These artifacts are the earliest datable replicas of fossils. Do they represent ancient efforts to figure out how the mysterious spirals had been formed? Were the fossils so valuable that forgeries were worthwhile? Were they objects of veneration? All we can say for sure is that from earliest antiquity, fossils were not only highly prized but artfully imitated.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times" (2011) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

April 4, 2012

The Mummy! & The Retrofuture

Kitwell House, where Jane imagined the 22nd century.

By Marri Lynn (W&M Regular Contributor)

Jane C. Webb wrote the The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century when science fiction was still a toddler, very shortly after Mary Shelley's Frankenstein helped to build the very nursery in which the genre would gain its legs.

When compared to most well-known nineteenth-century science fiction, The Mummy! is short on plot and strength of prose; but when read on its own merits, from the perspective of a historian or author, this oft-overlooked title has a lot to show us.

When it was published in 1827, The Mummy! caught the attention of John C. Loudon, a one-armed recovered opium addict and landscape architect. He was intrigued by the anonymous author's descriptions of inventive technologies that would serve him and his peers in their careers. Take, for example, a machine that draws down rainclouds for the express purpose of sparing you backbreaking hours with the watering can, or an automated, steam-powered lawnmower that I envision functioning a little like a coal-munching Roomba for your lawn.

Loudon would become intrigued by the author behind the ingenuity, discovering her to be an authoress only after a mutual acquaintance arranged a meeting face-to-face. The mutual acquaintance had unwittingly played matchmaker: Loudon and Webb hit it off, despite their age gap of twenty-four years, and were married eight months after their first rendezvous. This liaison led to the blossoming of Webb's fascination with gardening and the useful entry-level gardening advice books that came of it. It also meant the simultaneous rot of her budding career as an authoress of science fiction, a career path she had turned to when financial desperation in the wake of her father's death demanded she find an enterprise.

The Mummy! makes for an excellent study in the historical strengths and limitations of science fiction as a genre. It shows us how technological innovations are entertaining but meaningless when grafted on the back of stagnant social assumptions, even when authors make bold attempts to write above, or around, these extant social constructs by setting their stories centuries into the future. To be convincing, authors must envision social change that seems as fabulous as technological change. What Webb could and could not envision can (and should!) be read not merely as an authorial failing, but rather, as a means to gain insight into the late Georgian-era outlook.

In some ways, Webb's society of the twenty-second century was very forward-thinking: in an apparent combination of feminism and democracy, England is governed by elected queens; women are free to wear trousers, and universal education is free. But the queen's speeches and the statements of her supporters draw strongly on Victorian language and sexist ideals of women to justify a queen's rule. And while trouser-wearing they are, Webb's women of the twenty-second century are still very prone to getting the vapors and needing a man to wave the smelling-salts under their noses.

Webb took note of the scientific and developmental trends around her, projecting them into the future – sometimes without a full apprehension of their significance. We learn that England's topsoil has been thoroughly excavated, but rather than crop failure and a battle with erosion, the consequences are a springy turf which seems to amuse the British more than anything else. Webb wisely sensed the looming necessity for a more efficient means of communication across long distances, and pushed her technological imagination into devising a cannon-powered mail system . . . which seems rather disingenuous when you consider her depiction of the sky of the twenty-second century, a place highly trafficked by hot air balloons and more zany leisure and commuter craft than you can wave a zeppelin at.

(Be further warned that in this century, traumatic collisions and blood loss are still treatable by bloodletting.)

While the new generation of casually multilingual Brits enjoy their machine-conditioned air at home, and the convenience of a home telegraph machine, war overseas is still carried out by foot soldiers and horse-riding cavalry with the aid of gunpowder cannons.

But other anticipations of Webb's were closer to the mark, reflective of the burgeoning technological momentum of the industrial revolution of which we are the inheritors. Leather shoes are stamped out in one pressing at rapid factories, there are steam-powered machines for milking cows, and aerial bridges span the gulfs between England's new sky-scraping steeples.

Whether Webb's oversights and lack of craft are redeemed by the novelty of The Mummy! is a matter only resolved by individual reader taste. But what is more interesting to think about, should you peruse the pages of this under-studied classic, are the important examples with which Webb unwittingly provides us, in answer to modern questions: what insights can we find in the retrofuture, as an object of historical inquiry? What does good science fiction of today need in order to be considered timeless in the centuries to come?

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently studying French, while freelancing as a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

March 30, 2012

Historical novels: that marvelous blend of fact and fiction

It was a rather terrifying moment in my writing life. I had been asked to read from my novel about Mozart at a scholarly conference: the Mozart Society of America Even a prominent scholar from the Mozarteum in Salzburg was attending. Here were a group of people who had dedicated their lives to studying aspects of Mozart's life and music. (One or two were so scholarly that I have no idea what they were saying!) I got up rather tremulously and decided to be honest. I told them, "Thank you for all your hard work. I take your work, mix it with a little imagination and turn it into fiction." And to great surprise, they loved the scenes I read.

So is what the historical novelist writes fact or fiction? "Both," I say. "In a sensitive, creative, respectful and sometimes daring combination."

Many years ago, I had dinner in Oxford with the great Elizabethan scholar Dr. A.L. Rowse. There I confessed to him that I wanted to write Elizabethan historical fiction but felt shy about making up dialogue. His eyes widened and he said, "But of course you have to make it up!" That was my blessing to go forward and I was happy to dedicate one of my novels to him.

"How much is real? What is true?" I always hear these questions when I speak about my novels. I try to give an overall view. I say, "We can't know what great people said behind the closed bedroom door," and they all nod modestly in agreement. Behind closed bedroom doors – oh, of course not!

"But what is historical fiction?" people also ask and I reply, "It's fiction based on history." More, it is a dramatic piece and must tell an interesting, hopefully gripping story. To do that it must have a plot and dramatic highlights; it must not be repetitive or meander. Real lives do both. You must trim and shape real life into fictional form.

Shakespeare wrote historical fiction in his history plays. Some people have never forgiven him for making Richard III an evil guy, but Shakespeare was writing under the reign of the granddaughter of the man who dethroned Richard, so he shaped his character to something that would please her. He also has Henry V cry passionately before the Battle of Agincourt, "Once more unto the breach, dear friends!" In real life Henry might have said, "My boots hurt," but it would not be as memorable and not nearly as stirring.

We find facts in history books; we find living truth in historical fiction. And if a reader is introduced to an area of the past or a great historical figure she loves through fiction, she can always turn back to the work of historians. Nothing makes me happier as an author than to hear that I have made some part of history as real to readers as if they were transported to that time. I wanted to live then as well. It is because I love some periods of the past and certain people who lived within them so much that I became a writer.

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

March 27, 2012

Exam Question: Discuss the causes of World War I.

By Jack Beatty

It was easy filling up the blue book on that one. The war, we were taught, was over-determined to redundancy. "If the Sarajevo crisis had not precipitated a particular great war, some other crisis would have precipitated a great war at no distant time," writes one historian, summing up a long-regnant consensus of opinion that war was inevitable. In the last decade a new generation of historians has argued that it was "improbable," even "avoidable." My new book, The Lost History of 1914, is a contribution to that side of the debate. I discuss events within each of the Great Powers that, in some cases, came within days of derailing the war or deflecting it toward a different outcome. Up until the last days of July, for example, Britain verged on civil war between the Protestant North and the Catholic South over Irish Home Rule. On July 4, the Army Council warned the government that there were 200,000 armed men in Ireland; that if they clashed all available troops would be needed to restore order, including the "whole of the [British] Expeditionary Force" intended for France; and that if the BEF were used in Ireland, "we should be quite incapable of meeting our obligations abroad." Stipulate that the BEF could not be sent to France in early August. "If the BEF had not been sent," Niall Ferguson asserts, "there is no question that the Germans would have won the war…Hitler would have lived out his life as a failed artist and fulfilled soldier in a German-dominated Central Europe…" That is the kind of perspective on the war opened by the Lost History of 1914. To quote from a perceptive reviewer, my book seeks "to take apart what is known about 1914 and assemble it in a different form."

It was easy filling up the blue book on that one. The war, we were taught, was over-determined to redundancy. "If the Sarajevo crisis had not precipitated a particular great war, some other crisis would have precipitated a great war at no distant time," writes one historian, summing up a long-regnant consensus of opinion that war was inevitable. In the last decade a new generation of historians has argued that it was "improbable," even "avoidable." My new book, The Lost History of 1914, is a contribution to that side of the debate. I discuss events within each of the Great Powers that, in some cases, came within days of derailing the war or deflecting it toward a different outcome. Up until the last days of July, for example, Britain verged on civil war between the Protestant North and the Catholic South over Irish Home Rule. On July 4, the Army Council warned the government that there were 200,000 armed men in Ireland; that if they clashed all available troops would be needed to restore order, including the "whole of the [British] Expeditionary Force" intended for France; and that if the BEF were used in Ireland, "we should be quite incapable of meeting our obligations abroad." Stipulate that the BEF could not be sent to France in early August. "If the BEF had not been sent," Niall Ferguson asserts, "there is no question that the Germans would have won the war…Hitler would have lived out his life as a failed artist and fulfilled soldier in a German-dominated Central Europe…" That is the kind of perspective on the war opened by the Lost History of 1914. To quote from a perceptive reviewer, my book seeks "to take apart what is known about 1914 and assemble it in a different form."

—

Jack Beatty grew up listening to his father's memories of serving in WWI as a sailor on a ship torpedoed in the Bay of Biscay. He is a news analyst for "On Point," the public affairs program on National Public Radio, and the author of The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley, Colossus: How the Corporation Changed America, and Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900. He lives in New Hampshire.