Holly Tucker's Blog, page 84

March 23, 2012

On Swans, Death and Philosophy

Holy Swan by h.koppdelany via Flickr

There is a poignant moment about half way through the Phaedo, that eloquent dialogue depicting the death of Socrates, when Socrates likens himself to swans who sing most beautifully when they realize they must die. Socrates considers their's a song of joy, for they anticipate joining the god, Apollo, whose servants they are. But most humans, he says, because they fear death, consider the swan's song one of lament and sorrow (Phaedo, 84e-85a).

Scholars as early as the first century C.E. expressed doubt concerning the veracity of the Socratic account of the swan's song. Alexander of Myndos and Pliny the Elder were two who studied swans closely and found no evidence for the account to which Socrates gestures (Arnott, 150-1). Their research seems to support the long standing view of philosophy as detached from the natural world.

A bit more attention to the difference between the various species of swans, however, tells a different story. The mute swan, so called because it is normally silent save for some hissing and snorting during mating, would have been relatively common in Attica. Its cousin, however, the whooper swan, is less common, although it has been known to appear in that area in winter. Unlike the mute, the whooper sings, and due to the shape of its trachea, when it dies, it has been known to give out a slow, flute like wailing sound (Arnott, 152).

Socrates, of course, was not the first to speak of the swan song in connection with death; already in Aeschylus's Agamemnon, Clytemnestra compares Cassandra's "mortal lamentation" to a swan (Ag. 1444-5). Socrates' insistence, however, that the song is of joy, rather than lamentation is peculiar. This claim is made to reinforce the point that philosophy is the caring practice of dying (Phaedo, 67e), which turns out, however, to mean a specific way of living – one that speaks truth and seeks justice in one's relationships with others.

But that vision of philosophy seems to have itself become muted in the wake of Socrates' beautiful swan song. Many blame it on Plato himself, who is said to have been more concerned to write a philosophical system than his teacher, Socrates. That orthodoxy too, however, dissolves upon deeper consideration, for dialogues are not treatises, and the proper interpretation of Plato remains elusive, as the dream he is said to have had briefly before his death suggests:

When he was about to die, he saw in a dream that he became a swan moving from tree to tree and in this way caused much trouble to the birdcatchers. Simmias the Socratic judged from this, that he would not be captured by those desiring to interpret him (Olympiodorus, 2. 156-9).

References

Aeschylus, J. D. Denniston, and Denys Lionel Page, Agamemnon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960).

W. Geoffrey Arnott, "Swan Songs," Greece and Rome 24, no. 2 (1977): 149-153.

Brann, E., Kalkavage, P., & Salem, E. (Eds.). (1998). Plato : Phaedo. (E. Brann, P. Kalkavage, & E. Salem, Trans.). Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company.

Olympiodorus. Commentary on the first Alcibiades of Plato. Ed. Leendert Gerrit Westerink. A.M. Hakkert, 1956.

March 22, 2012

From Top Secret Weapon to Everyday Household Appliance

by Larry Phillips (Atlanta Science Tavern contributor)

In September of 1940 the British scientist Henry Tizard arrived in Washington DC on an official visit. Tizard had with him a carefully packed trunk containing a device that an American official later described as "the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores". The device was a top-secret invention called the "cavity magnetron", and it was the key to making radar workable. Tizard's mission was to persuade the US military to fund further development of magnetron-based radar.

Randall and Boot cavity magnetron (credit: Wikimedia Commons user geni)

To understand the cavity magnetron's role in radar technology, let's review what an effective radar system needs. First, radar determines the range of a target by timing how long it takes for a transmitted radio pulse to bounce off the target and return to the source. If this faint echo is to be detectable, the outgoing pulse must be quite powerful– ideally, thousands of watts of power.

Second, the pulse needs to be sent out in a narrow beam. Otherwise, we will not know the direction of the target. A typical radar system scans across the horizon, continuously sending out its narrow beam of pulses. When an echo comes back, we know that the target is in that direction. Because of the way radio waves work, a narrow beam can only be produced if the radio waves are of very high frequency (or equivalently, of short wavelength). High frequency radio also has the advantage of bouncing more readily off small objects, such as airplanes.

These two requirements, high power and high frequency, presented a technical problem that vacuum tubes and other devices could not solve. The magnetron met both these requirements. Indeed, the American scientists who tested Tizard's device were astonished to find that it produced 1,000 times the power level of anything they had.

The Americans wisely accepted the Tizard offer, and they began a large-scale effort to exploit the magnetron breakthrough. In time, this effort rivaled the Manhattan Project in size, and it resulted in American and British radar that was much better than their German and Japanese counterparts had. Airborne radar was so sensitive that it could detect submarine periscopes, and shipping loses to German submarines declined dramatically.

Even so, radar had produced its biggest impact on the war before Tizard arrived in 1940. The British had fended off the German bombing campaign in The Battle of Britain largely because their radar had enabled them to have their fighter planes in the air when the German bombers arrived over the English Channel. Fortunately, the Nazis never understood how good the British radar was; they were simply baffled by how Britain's small air force was able to down so many of their bombers.

In the 72 years since Tizard's visit, the cavity magnetron has gone from super-secret war weapon to commonplace: every microwave oven uses one to produce its microwaves.

Larry Phillips is a former electrical engineer and software developer at Lucent Technologies and Bell Laboratories. He now tutors students in mathematics and physics, writes a blog on mathematics at BrightStarTutors, and is author of a forthcoming book titled The Elementary Mathematics of Gravity.

March 20, 2012

The peril of torphuts

by Tracy Barrett, W&M contributor

Ah, the joys of research. You find exactly the detail you need to round out a character's personality, or an artifact that will enable your plot to develop in the way that you want. Or you stumble upon something that you hadn't been looking for, but which takes you in a direction that you hadn't thought of but that enriches your manuscript. There's a flip side, of course. Some integral object turns out to have been invented centuries after the time when your story is based, or a character died before she could have met your protagonist.

And then there are the wonderful, quirky details you can't use. They're irrelevant or distracting. It's so hard to let them go, reluctantly watching a weird item float away because you just can't work them into your story.

I recently found one of those, and although I haven't given up, I'm still trying to figure out a way to use it.

Yum!

Most ancient history buffs know about garum—the sauce made of fermented fish (guts included) that the Romans were addicted to. It was stinky stuff. (But loaded with umami, it turns out.)

Garum factory in Spain

Despite their love for it, the Romans forbade its manufacture within city walls. It's so pungent that when some jars labeled "GARUM" were opened after lying on the sea bed for millennia, they reputedly still smelled of it. The city of Pompeii was well known for its high-quality garum.

Being a port, Pompeii was also a very multicultural city. Its merchants catered to customers from a wide variety of cultures, many of whom observed specific dietary laws. When some jars of garum labeled "castum" (pure) were found, scholars wondered—pure in what sense?

Being a port, Pompeii was also a very multicultural city. Its merchants catered to customers from a wide variety of cultures, many of whom observed specific dietary laws. When some jars of garum labeled "castum" (pure) were found, scholars wondered—pure in what sense?

At least some scholars believe it means "kosher."

Kosher garum! How can I work it into my story? The last thing I want to do is to use it for its own sake. That always winds up being clunky. I recently tried to read a novel set in the Middle Ages and gave up after too many passages like this one:

Janekin had been engaged in a battle of words with the young citizens who supported Henry, duke of Lancaster, in his struggle with King Richard. Janekin was of the king's party and wore a pewter badge of the white hart in his tall hat of felt. John of Gaunt, father of Henry, had died seven weeks before. Now King Richard had revoked Henry's inheritance, keeping the Lancastrian legacy for his own use, and had consigned Henry to perpetual banishment. Janekin had been watching some Lancastrian supporters at the corner of Ave Maria Lane, and had called out "Torphut! Torphut!" as a signal of his contempt. Two of them heard this and ran in chase of Janekin, who turned upon his heels and fled down the lane.

Now, I'm all for period detail to add richness to a scene. The pewter badge in a tall felt hat is a nice touch—I hadn't pictured Janekin in a tall hat until then. Ave Maria Lane is a nice name. But it goes into overload. Do we really need to know the details of the tussle for the throne? And what the heck is "torphut"? Okay, I get that it's an insult. But what does it mean?

The OED didn't help. A google search turned up only this same passage. I have no doubt that the author found the word in some document someplace and it had such a nice insulting sound that he just had to use it.

It didn't work for me—it pulls me out of the story. I wish he had resisted the impulse and had found another insult to use.

So from now on I'm going to call those interesting facts that you're dying to use but really shouldn't "torphuts." And I vow to avoid them.

March 16, 2012

A Crusade by Any Other Name

By Pamela Toler

Sometimes the name you give to an historical event says a lot about where you stand in relation to that event. Is it the Civil War, or the War of Northern Aggression? The Sepoy Rebellion, the first Indian war of independence, or (my personal choice) the violence of 1857?

Sometimes the name you give to an historical event says a lot about where you stand in relation to that event. Is it the Civil War, or the War of Northern Aggression? The Sepoy Rebellion, the first Indian war of independence, or (my personal choice) the violence of 1857?

Other times, what you call an event can be the marker of a cultural blind spot. I certainly felt like I'd received a well-deserved smack up the side of the head when I recently picked up Amin Maalouf's

The Crusades Through Arab Eyes and read on the very first page that medieval* Arab historians and chroniclers "spoke not of Crusades, but of Frankish wars or 'the Frankish invasions' ". Duh!

I've been reading seriously about the Crusades for several years now. I am well aware that the term "crusade" derives from the red cross worn by warriors who had "taken the cross". If pushed to choose a side, I'd back the cultured Muslims against the barbaric "Frankish invaders" any day. But I'm also a product of my time, my place, and my education. In my head, it's the Crusades. Or at least it was until an expatriate Arab Christian from Lebanon pointed out the obvious. Thanks, Mr. Maalouf. I needed that.

What cultural blind spots have you found lately?

*Another culturally charged word. Technically the Middle Ages refers to the period in European history between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

This post previously appeared in History in the Margins.

March 14, 2012

Who buys used postcards anyhow?

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

The 'archival jolt' happened in the strangest of places, a Brighton fleamarket. Idly rummaging through the detritus of people's lives in search of treasure, I found a large box filled with used postcards, and I wondered who on earth would purchase such a useless thing. Of course, the snoop in me couldn't resist a quick peek. I happily rooted through thank you notes, accounts of holidays, radio contest answers, and invitations, before finding some blank ones from the early twentieth century. These, at least, might be added to my stationary stash!

With disappointment I realised that several of the old postcards had, in fact, been ruined by small scrawled initials: 'V.L.L.' I scanned initialled card after initialled card, finding no truly blank ones. It was then that the jolt struck: who was this person? And what was the significance of this postcard collection?

Aided by my husband, who joined my quest, I amassed a large pile of initialled cards, all with dates from the 1920s. We had both been hooked by the mystery of V.L.L.'s cards. But thinking like a historian, I was at a loss to know how to analyse the essentially blank texts that provided no clues to the sex, name, or purpose of the collector.

My husband and I left the fleamarket, but all day our conversation returned to the postcards, as we imagined the story of V.L.L.'s cards, which were from all around Europe. Perhaps V.L.L. had been a former soldier or military nurse who had gotten a taste for travel while in service. Perhaps V.L.L. was merely an armchair traveller whose friends brought back pictures of their own trips. Or perhaps V.L.L. was a war widow, who took up a life of travel instead of remarriage. The fictive possibilities were endless, exhilarating.

The next morning found my husband and me in possession of a large garbage bag filled with five pounds of unsorted postcards, wondering how to get them back home.

And now that I know who buys used postcards, a bigger question remains: what am I going to do with them?

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800), but has always had a soft spot for the early-twentieth century.

Juana of Castile's Baggage

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (W&M Regular Contributor)

Imagine being known to history as Juana "la Loca" or Juana "the crazy one." That is heavy baggage to carry forward from the sixteenth century into the postmodern era. Before she was Juana la Loca, she was Juana of Castile (1479-1555), the eldest surviving heir of the famous monarchs Isabel of Castile (r. 1474-1504) and Fernando of Aragon (r. 1474-1516). When her mother died in 1504, earlier marriage capitulations made it impossible for her father to inherit the throne, making Juana the rightful sovereign of Castile. Yet her ambitious father and her husband, Philip the Fair (1478-1506), sought to break this neat line of succession and push her off the political stage. In part, they used rumors of her instability to discredit her authority. When Philip died unexpectedly in the city of Burgos in 1506, Juana's behavior unfortunately fueled the flames of her detractors. She insisted upon accompanying her husband's funeral cortege across the Iberian peninsula from Burgos to his final resting place in Granada. Fernando presented this act of wifely devotion and other emotional outbursts as evidence of mental illness and advanced his own claims to the throne. He eventually forced her seclusion in a convent in the small town of Tordesillas.

Fernando presented this act of wifely devotion and other emotional outbursts as evidence of mental illness and advanced his own claims to the throne. He eventually forced her seclusion in a convent in the small town of Tordesillas.

Fernando died in 1516, leaving behind Juana and her son, Charles I (1500-1558), as his heirs. Despite her confinement, Charles continued to consult with her and maintained the pretense of joint rule with his mother. A group of urban leaders who were dissatisfied with Charles' long absences from Castile and reliance on foreign advisers even appealed to Juana during a revolt they staged in 1520-21. Some clearly believed she could still exercise independent sovereign power.

But in the end, later generations would immortalize her for her presumed, but never proven, insanity. Juana's plight captured the attention of nineteenth century Romanticists, for example, who sentimentalized her devotion to Philip in paintings like this one above by Francisco de Pradilla, produced in 1877. This haunting portrait speaks volumes about history's distorted image of a misunderstood queen. In 2001 a Spanish movie, "Juana la Loca," (translated for English-speaking audiences as "Mad Love") perpetuated this interpretation of Juana's instability.

Recent scholarship has sought to investigate the true character of Juana's personality and exercise of political authority (see, for example, Bethany Aram, Juana the Mad: Sovereignty and Dynasty in Renaissance Europe, 2005). It reveals that she often rejected the power that she was entitled to, but she was not insane. At some moments she worked vigorously to assert her sovereignty and her control over her royal household. Only time will tell if interpretations like this are enough to rid Juana of the weighty baggage of being portrayed as a mentally unstable queen.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

March 11, 2012

The Turn Of The Leg

The Apollo Belvedere

Much is often made of Beau Brummell's unique and lasting contributions to fashion, but in the interest of citing one's sources, it's important to clarify just exactly who — or what — old George was modeling himself on.

Because just around the time that a young George Brummell was setting up house at 4 Chesterfield Street in Mayfair, the Apollo Belvedere had just made its way to London for exhibit, having been recently looted from Rome by that noted art appreciator and collector Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796.

It wasn't the first time London had laid eyes on this Apollo, of course. This sculpture had been copied and revered for hundreds of years as the pinnacle of classical beauty. Casts and sketches of it littered virtually every artist's studio and museum, and it wasn't uncommon for English gentlemen of wealth and status to have themselves painted in the same pose.

But the mania for all things classical had now taken hold in a way it never had before. Everything from home decor to ladies' muslin dresses were modelled on the classical ideal.

So the time was ripe for the allure of Apollo to hold sway over one very influential young man. And through him, the rest of the fashionable world.

The similarity of George Brummell's features and build to that of the most famous statue in classical antiquity was remarked on at once by Brummell's fawning admirers.

A friend sighed:

Nature had indeed been most liberal to him… he was about the same height as Apollo and the just proportions of his form were remarkable… and, had he been inclined to earn his livelihood… he would readily have found an engagement as a life sitter to an artist, or got paid to perambulate… from fair to fair, to personate the statues of the ancients.

Brummell, it should be noted, did absolutely everything he could to encourage the comparison.

Brummell set a new standard for fashion, and it's sad that the passing of time has given him and his "dandy set" such a bad rap. Because rather than persist in the Rococo excesses of their fathers and grandfathers, Beau and his gang tossed aside wigs and powder, silk and velvet, all in favor of a far more restrained mode of dress.

Somber colors. Simple linen. Impeccable tailoring. Tight fit.

Statue of Beau Brummell in Jermyn Street, London

In particular, the style of trousers favored by the Beau and his set was meant specifically to emulate the classical form found in art such as the Apollo Belvedere. Even the creamy pale shade of fabric they favored for their trousers, which was framed so starkly by a dark, cutaway jacket and polished Hessian boots, was meant to evoke the smooth paleness of marble.

In short, the goal was to appear, as near as possible, quite naked from the waist down.

Not surprisingly, this new fashion led to the wholesale jettisoning of the undergarments, or "small clothes" on the part of this set of fashionable young men. Since the goal was to appear to have a form as smooth and idealized as a classical Greek sculpture, one could hardly allow this vision of loveliness to be broken up by something as outré as a pantyline.

No supporting underclothes beneath pale, tight trousers, of course, meant that suddenly the public eye was quite firmly fixed on a young man's, ah, princely estate. And there were few secrets that went unrevealed, shall we say. Not since the codpiece of Tudor days had the joining of the male thighs been so much the focus of sartorial splendor.

It's even been suggested that the approving phrase "a fine turn of the leg," popular in novels and plays of the time as an appreciative comment on the male form, was to be understood euphemistically.

If you catch my drift.

It will perhaps not surprise you to discover that Lord Byron was a particular fan of the rise, so to speak, of this new mode of dress, and he did his utmost to champion it. And Byron was just as cognizant as any of the relationship of the new style to that of classical figures like the Apollo.

His praise for the Apollo was unstinting. He even suggested that by the creation of this one marble sculpture, humanity had discharged the debt we owed to Prometheus for the gift of fire.

And if it be Prometheus stole from Heaven

The fire which we endure, it was repaid

By him to whom the energy was given

Which this poetic marble hath array'd

With an eternal glory–which, if made

By human hands, is not of human thought;

And Time himself hath hallowed it, nor laid

One ringlet in the dust–nor hath it caught

A tinge of years, but breathes the flame with which 'twas wrought.

- Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, IV, CLXIII, 161-163; 1459–67

Sadly, Brummell did not enjoy the nearly unlimited resources of his friend Lord Byron, and would soon find himself hounded out of London society. Riddled with debt, spurned by his old patron the Prince Regent, and already suffering from the syphilis that would eventually kill him, he fled for France in 1816, just seventeen years after beginning his glittering career as a center of fashionable London life.

By then, of course, Napoleon had fallen for the last time at Waterloo, and the Apollo Belvedere was returned to the Vatican where it remains to this day. The generation that followed — including influential critic John Ruskin and others — would turn on the ideals of Brummell's day, disparaging the lofty formality of Apollo's classical lines. Mind you, this is the Victorian crowd that brought back the fig leaf, among other dubious artistic innovations.

But the old style was not to disappear without regret. It was said that the ladies particularly lamented the passing of the pale, tight, pantyless trouser.

For it was said that in those days "one could always tell what a young man was thinking."

Indeed.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady and contemplates the trousers of 19th century gentlemen just a little bit more than is entirely seemly. Even for a romance novelist.

To read more about Beau Brummell's life and contributions to fashion, get your hands on the excellent biography of Brummell by Ian Kelly, The Ultimate Man of Style, to which this article owes much. Including, one imagines, an apology.

March 9, 2012

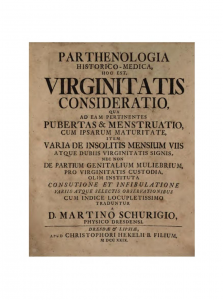

Vicarious menstruation

Historical accounts of 'male menstruation' have already been discussed on this blog by Lisa Smith. But there is another aspect of the history of menstruation that is fascinating to a modern reader: the phenomenon of 'vicarious menstruation', in which a woman bleeds regularly from another orifice, or even from a wound. While modern medicine still recognises conditions in which other mucous membranes bleed along with, or instead of, the womb lining, the cases from the past seem to be well outside what is thought to be possible today. I think this is one of those occasions on which attempts to diagnose the diseases of the past with modern disease labels just have to admit defeat. The belief in such diversion being possible goes back to the Hippocratic medical texts, which state that a nosebleed is a good thing if menstruation is suppressed.

Historical accounts of 'male menstruation' have already been discussed on this blog by Lisa Smith. But there is another aspect of the history of menstruation that is fascinating to a modern reader: the phenomenon of 'vicarious menstruation', in which a woman bleeds regularly from another orifice, or even from a wound. While modern medicine still recognises conditions in which other mucous membranes bleed along with, or instead of, the womb lining, the cases from the past seem to be well outside what is thought to be possible today. I think this is one of those occasions on which attempts to diagnose the diseases of the past with modern disease labels just have to admit defeat. The belief in such diversion being possible goes back to the Hippocratic medical texts, which state that a nosebleed is a good thing if menstruation is suppressed.

In 1838 the physician Fleetwood Churchill described a case a colleague had seen: Mary Murphy, aged 21, a patient at Sir Patrick Dun's teaching hospital in Dublin. 'During her stay she missed a menstrual period, and was shortly afterwards attacked by hemorrhage from both ears, which was repeated at intervals of from three to five nights, each attack lasting some hours. Very often from 15 to 20 ounces of blood were collected which did not coagulate, neither did blood taken from the arm.' 15-20 ounces: that's half a litre. Today we see a 'normal' period as being around 80 millitres or 3 fluid ounces! She was treated by 'strengthening her system', with foot baths, purgative medicines, and also leeches. The leeches were applied behind her ears and on her inner thighs, to take the blood before it came out, and to divert it back down her body.

The high point of belief in such bleeding was Martin Schurig's Parthenologia historico-medica (1729), which brought together a huge range of cases from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to include menstruation through the ears, skin, gums, saliva glands, tear ducts, the crown of the head, fingers, feet, the stomach and lungs, the bladder, the bowels, the back, the navel, and even a cut on the hand, because 'Nature searches for an exit route for the menstrual blood'. Physicians noted that the first reaction of a physician when confronted with 'a delicate female' suffering from such bleeding may be 'alarm and anxiety'. What about the reactions of the patients, I wonder?

In the UK, 'vicarious menstruation' was only really challenged in the late 1880s, when the British Gynaecological Society discussed a paper by Dr Robert Barnes entitled 'On vicarious menstruation' which defended the theory of the blood taking the path of least resistance if 'the normal route fails'. My late grandmother was born in 1888 and it is amazing to think that such a theory lasted so long!

- if you want to know more about Fleetwood Churchill, see http://rcpilibrary.blogspot.com/2010/...

March 6, 2012

The World's First Robot: Talos

by Adrienne Mayor, Wonders & Marvels contributor

Uncanny mechanical humanoids, automatons, robots, and replicants, so popular in modern fiction and film, are usually thought to be inventions of the 17th century (Louis IV commissioned several mechanized figures). But the creation of artificial humans is a very ancient dream—or nightmare. Daedalus, the most ingenious inventor of Greek myth, was credited with making many marvelous mechanical wonders. His well-known experiment with man-made wings ended tragically with the death of his son Icarus., but Daedalus also created the first "living statues." These realistic bronze sculptures appeared to be endowed with life as they moved their limbs, rolled their eyes, perspired, wept, and vocalized. Such animatronic statues were not just figments of the mythic imagination—they were actually constructed in classical antiquity.

Robots made to obey commands were also engineered by Hephaestus, the Greek god of invention and technology. Talos, the gigantic animated bronze warrior programmed to guard the island of Crete, was one of Hephaestus's creations. Like Hollywood's imaginary Robo-Cop or the Terminator, Talos was the ancient forerunner of autonomous cyborgs capable of deploying lethal force.

The physiology of Talos, described by ancient writers in mytho-bio-technical language, seems to presage today's scientific "cybernetic organism" projects that employ neurological-computer interfaces to integrate living and non-living components. Hephaestus gave Talos a single internal artery or vein, through which ichor, the mysterious life-fluid of the gods, pulsed from his neck to his ankle. Talos's biomimetic "vivisystem" was sealed by a single bronze nail.

Talos was tasked with hurling boulders at passing ships, including the Argo, manned by Jason and the Argonauts. But the most chilling ability of the huge biomechanical robot was a perversion of the universal gesture of human warmth, the embrace. Talos could heat his bronze body red-hot and then clasp a victim in his arms, hugging and burning him to death. How could Jason and the Argonauts escape from this bionic monster? Techno-wizard Medea to the rescue! Anticipating by more than 2,000 years HAL the doomed artificial intelligence computer of 2001: A Space Odyssey and the tragic replicants of Bladerunner, the sorceress Medea recognized the popular belief that that all artificial humanoids must harbor a deep desire to be real humans. Medea hypnotized Talos and convinced him that she could make him mortal by removing the bronze nail in his ankle. When this essential seal was dislodged, the ichor flowed out of Talos like molten lead, and his life ebbed away.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World" (2009) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

March 1, 2012

"One night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury:" Syphilis and "Syphilophobes" in Early Modern England

Skeleton (c. 18th century) showing signs of advance syphilis.

Before the discovery of penicillin in 1928, syphilis was an incurable disease. Its symptoms were as terrifying as they were unrelenting. Those who suffered from it long enough could expect to develop unsightly skin ulcers, paralysis, gradual blindness, dementia and "saddle nose," a grotesque deformity which occurs when the bridge of the nose caves into the face.

The seventeenth century was particularly rife with syphilis. Because of its prevalence, both physicians and surgeons treated syphilitic patients. Many treatments involved the use of mercury, giving rise to the saying: "One night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury." Mercury could be administered in the form of calomel (mercury chloride), an ointment, a steam bath or pill. Unfortunately, the side effects could be as painful and terrifying as the disease itself. Many patients who underwent mercury treatments suffered from extensive tooth loss, ulcerations and neurological damage. In many cases, people died from significant mercury poisoning.

Given the nature of syphilis, as well as its therapeutic alternative, it is not a surprise that many people developed a phobia of the disease. "Syphilophobes" feature frequently in seventeenth-century medical literature. Richard Wiseman, a surgeon from the period, writes: "These men will strangely imagine all the pains and other Symptoms they have read of, or have heard other men talk of. Many of these hypochondriack have come to [me]. They commonly went away…unsatisified, nor could they quiet their minds till they found some undertake that would comply with them."[1]

When a surgeon or physician failed to provide the desired diagnosis, syphilophobes often turned to quacks, who frequently traded on the fears of their patients. Quacks promised quick and immediate cures for the syphilophobes' imaginary symptoms. Wiseman naturally expressed his scepticism: these patients "were never the better, the imagination in which the Disease was seated remaining still uncured; whereupon presuming they were not in hands skilful enough, they have gone to others and so forwards, till they have ruined both their Bodies and Purses." [2]

Today, syphilophobes are few and far between thanks to the wonders of penicillin; however, there are people who still suffer from a general fear of venereal diseases. Cypridophobia is named after the Greek island, Cyprus, where legend has it the Goddess, Venus, was born. Although it is rare, those who suffer from it can at least rest assured that 'one night with Venus' does not lead to a "lifetime with Mercury" in this day and age.

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon's Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

2. Ibid.