Holly Tucker's Blog, page 81

June 13, 2012

Who Are You?

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders & Marvels)

As many of you know, my two passions are history and science. Or better yet: History of Science.

And when I see a good idea, I have no problem imitating it…

Over at Scientific American’s Not Exactly Rocket Science, science writer Ed Yong has turned the microphone over to his readers. Once a year, he asks folks to introduce themselves. Who are you? What draws you to the blog? How long have you been reading it? What do you think about it? How can it be improved?

At the risk of being a copycat, let’s give that a shot here too! Tell me more about YOU. What draws you here? What’s your background? What would you love to see more of?

Com’on! Don’t be shy…

June 9, 2012

Midwifery and ventriloquism: did Elizabeth Cellier write her own books?

Possibly my favourite historical figure of all time is Elizabeth Cellier, the ‘Popish Midwife’ who was involved in one of those complicated ‘plots’ of late seventeenth-century England; the ‘meal-tub plot’, in which a list of plotters turned up in her kitchen. Was it genuine, or planted by those who wanted to represent Roman Catholics as a threat to social order? She published some pamphlets defending her innocence, but ended up in the pillory after making allegations she couldn’t prove. She then returned to the historical spotlight in 1687, when she put forward a proposal for a College of Midwives in which the membership fees would fund a foundling hospital, thus hopefully reducing rates of mortality in childbirth while at the same time looking after unwanted babies.

Possibly my favourite historical figure of all time is Elizabeth Cellier, the ‘Popish Midwife’ who was involved in one of those complicated ‘plots’ of late seventeenth-century England; the ‘meal-tub plot’, in which a list of plotters turned up in her kitchen. Was it genuine, or planted by those who wanted to represent Roman Catholics as a threat to social order? She published some pamphlets defending her innocence, but ended up in the pillory after making allegations she couldn’t prove. She then returned to the historical spotlight in 1687, when she put forward a proposal for a College of Midwives in which the membership fees would fund a foundling hospital, thus hopefully reducing rates of mortality in childbirth while at the same time looking after unwanted babies.

Midwives in this period had a complicated relationship with truth, and with words more generally. They were supposed to keep the secrets of those they served, but were allowed to tell a few lies if the purpose was to comfort a woman in labour. When Cellier was on trial for publishing a libellous pamphlet, she claimed that her status as midwife meant her testimony could be trusted; handling information as part of her job meant she knew what to say, and when. But as a woman, a midwife, and also a Catholic, she was seen as a particularly tricky customer! In her evidence to the courts she tried to walk a tightrope between forthright speech – which meant she ran the risk of being seen as ‘too masculine’ – and proper womanly modesty (which, I suspect, did not come easily to her!). One of her political opponents wrote that “When a Woman has once lost her Modesty she is fit for all sorts of Mischief” and, as a woman on at least her second husband, Cellier was accused of a range of extramarital relationships with a string of lovers including a young Spaniard whom she instructed in “the School of Venus, &c”. Talk, of course, is cheap.

One of her opponents claimed that her political pamphlets were not written by her, but were the product of “a priest got into her Belly, and so speaking through her, as the Devil through the Heathen Oracles” (incidentally, that’s an interesting 17th c approach to the ancient Greek oracle at Delphi). Modern scholars have wondered whether she wrote the midwifery proposal, or whether she was the front woman for a male midwife trying to take over midwifery in London. But I suspect her words are her own. Her midwifery writing shows that she owned books by men – such as Jacques Guillemeau – but she gives their words her own spin. She claims she has “small Learning and weak Capacity”, but that’s only an attempt to put her accusers off the scent. She comes across as witty, well-read, and able to play with the stereotypes of the midwife; she gives as good as she gets. She wrote, “I hope the God of Truth and Justice will protect me, and bring me through them all, and pluck off the vails, and discover both Truth and Frauds bare-faced”. Go, girl!

Sources:

Cellier, Elizabeth (1680) Malice Defeated, or, A brief relation of the accusation and deliverance of Elizabeth Cellier wherein her proceedings both before and during her confinement are particularly related and the Mystery of the meal-tub fully discovered : together with an abstract of her arraignment and tryal, written by her self, for the satisfaction of all lovers of undisguised truth, London

— (1687) A Scheme for the Foundation of a Royal Hospital, and Raising a Revenue of Five of Six-thousand Pounds a Year, by, and for the Maintenance of a Corporation of skilful Midwives… London

Torturing the Dead: The Prevention of Premature Burial and Dissection

By Lindsey Fitzharris (W&M Contributor)

In 1746, Jacques-Bénigne Winslow wrote: “Tho’ Death, at some Time or other, is the necessary and unavoidable Portion of Human Nature in its present Condition, yet it is not always certain, that Persons taken for dead are really and irretrievably deprived of Life.” Indeed, the Danish anatomist went on to claim that it was “evident from Experience” that those thought to be dead have proven otherwise “by rising from their Shrowds [sic], their Coffins, and even from their Graves.” [1]

Fears over premature burial were ubiquitous in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1792, the first “safety coffin” was constructed for Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick which included a window to allow light in and a tube to provide a fresh supply of air. The lid of the coffin was then locked and two keys were fitted into a special pocket sewn into his burial shroud: one for the coffin itself and one for the tomb. Similar constructions followed, including coffins designed with signalling mechanisms to allow the person buried below to notify those above that he or she was not dead.

Perhaps even worse than premature burial was the thought of being dissected while still alive. The 19th-century physician and surgeon, Sir Robert Christison, complained that dissection in St Bartholomew’s Hospital was “apt to be performed with indecent, sometimes with dangerous haste.” He wrote:

It was no uncommon occurrence that, when the operator proceeded with his work, the body was sensibly warm, the limbs not yet rigid, the blood in the great vessels fluid and coagulable [sic]. I remember an occasion when [William] Cullen commenced the dissection of a man who died on hour before, and when fluid blood gushed in abundance from the first incision through the skin…Instantly I seized his wrist in great alarm, and arrested his progress; nor was I easily persuaded to let him go on, when I saw the blood coagulate on the table exactly like living blood. [2]

The 17th and 18th centuries were rife with stories about executed criminals who had “returned from the dead” just moments before being dissected. In 1651, Anne Greene was hanged in Oxford for infanticide. For thirty minutes, she dangled at the end of the noose while her friends ”thump[ed] her breast” and put “their weight upon her leggs [sic]…lifting her up and then pulling her downe againe with a suddain jerke” in order to quicken her death. Afterwards, her body was cut down from the gallows and brought to Drs Thomas Willis and William Petty to be dissected. Just seconds before Willis plunged the knife into her sternum, Anne miraculously awoke. [For more about Anne Greene, click here]. [3]

Anatomists, themselves, worried about the precise moment of death when cutting open the bodies of the recently dead. To avoid disaster, Winslow suggested that a person’s gums be rubbed with caustic substances, and that the body be “stimulate[d]…with Whips and Nettles” before being dissected. Furthermore, the anatomist should “irritate his Intestines by Means of Clysters and Injections of Air or Smoke,” as well as “agitate…the Limbs by violent Extensions and Inflexions.” If possible, an attempt should also be made to “shock [the person’s] Ears by hideous Shrieks and excessive Noises.” [4]

Anatomists, themselves, worried about the precise moment of death when cutting open the bodies of the recently dead. To avoid disaster, Winslow suggested that a person’s gums be rubbed with caustic substances, and that the body be “stimulate[d]…with Whips and Nettles” before being dissected. Furthermore, the anatomist should “irritate his Intestines by Means of Clysters and Injections of Air or Smoke,” as well as “agitate…the Limbs by violent Extensions and Inflexions.” If possible, an attempt should also be made to “shock [the person’s] Ears by hideous Shrieks and excessive Noises.” [4]

To our modern sensibilities, these measures may seem extreme, even comical, but to Winslow, this was no laughing matter. In fact, he went even further, recommending that the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet be pricked with needles, and that the “Scapulae, Shoulders and Arms” be scarified using fire or sharp instruments so as to “lacerate and strip [them] of the epidermis.” [5] Indeed, when reading Winslow’s work, one gets the innate feeling that he took pleasure in imaging new ways to torture the dead.

That said, it wasn’t just medical practitioners who came up with ways of testing whether a person was dead or not. Family and friends of the deceased also devised methods for ensuring that their loved ones were not prematurely buried, including shouting the name of the person and poking his or her eyes. Most commonly, the body of the recently deceased was watched for a period of 3 days before burial, during which time putrefaction and decay would have become evident.

Of course, there were situations that warranted immediate burial of the body, as in the case of plague victims. In these instances, there was no time to wait for the body to begin decomposing. In his book, Winslow recalls the story of a man in Rome whom, upon being “accounted dead,” was to be “interred with the utmost Expedition.” As his body was being carried over the Tiber River to the plague pit, the boatman “discovered some Signs of Life” and brought the young man back to the hospital “where he perfectly recovered Life.” Two days later, however, the man fell back into a similar state and was “judged irreparably dead.” His body was “without any farther [sic] Hesitation laid among those destin’d for the Grave.” Once again, to the horror of those around him, the man “returned to Life” and escaped premature burial for a second time. [6]

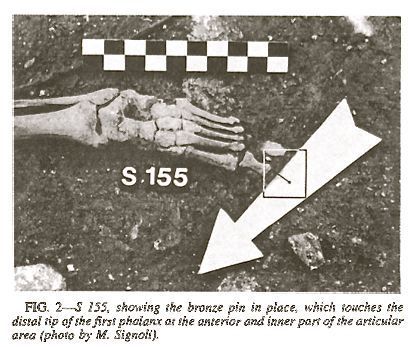

Recently, archaeologists found evidence that bronze pins were implanted in the “palmar surface of the hands, scapular area, under the plantar surface of the feet, and…under the toe nails” of plague victims in Marseilles. The position of the skeletons in the mass graves also suggest that the dead were given “fast burials” as rigor mortis, which typically appears six hours after death, had not set in before the plague pit was covered over. In the midst of a plague outbreak, one can easily imagine how some people may have been mistaken for dead before being dumped into a pit of rotting corpses. [7]

Recently, archaeologists found evidence that bronze pins were implanted in the “palmar surface of the hands, scapular area, under the plantar surface of the feet, and…under the toe nails” of plague victims in Marseilles. The position of the skeletons in the mass graves also suggest that the dead were given “fast burials” as rigor mortis, which typically appears six hours after death, had not set in before the plague pit was covered over. In the midst of a plague outbreak, one can easily imagine how some people may have been mistaken for dead before being dumped into a pit of rotting corpses. [7]

Today, our societal fears over premature burial have dwindled considerably. However, new debates have arisen over the very definition of death itself with the emergence of “beating heart cadavers.” Though considered dead in both a medical and legal capacity, these “cadavers” are kept on ventilators for organ and tissue transplantation. Their hearts beat; they expel waste; they have the ability to heal themselves of infection; they can even carry a foetus to term. Crucially, though, their brains are no longer functioning. It is in this way that the medical community has redefined death in the 21st century. [8]

Yet, some wonder whether these “beating heart cadavers” are really dead, or whether they are just straddling the great divide between life and death before the finally lights go out.

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

1. Jacques-Bénigne Winslow, The Uncertainty of the Signs of Death, and the Danger of Precipitate Interments and Dissections (1746), pp. 1-2.

2. R. Christison, The Life of Sir Robert Christison (1885-6), pp. 192-3. Originally quoted in Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (2000), p. 98.

3. Richard Watkins, News from the Dead (1651), p. 2.

4. Winslow, The Uncertainty of the Signs of Death, p. 21.

5. Ibid., p. 23.

6. Ibid., pp. 4-5.

7. Georges Leonetti, et al., “Evidence of Pin Implantation as a Means of Verifying Death During the Great Plague of Marseilles (1722),” in Journal of Forensic Science 42:4 (1997), pp. 744 – 748.

8. For more on “beating heart cadavers” and new definitions of death, see Dick Teresi, The Undead: Organ Harvesting, the Ice-Water Test, Beating-Heart Cadavers—How Medicine is Blurring the Line Between Life and Death (2012).

June 6, 2012

Ancient Flying Saucers

“Ancient Aliens,” the popular sci-fi meme, has yet to produce solid proof that extraterrestrials ever interacted with humans. Yet Unidentified Flying Objects have a surprisingly ancient history. The earliest UFO sightings were reported by Roman historians Livy, Orosius, Seneca, Plutarch, Pliny, and Josephus. The ancient sightings have been classified by a NASA scientist according to the standard UFO categories devised by astronomer J.A. Hynek (1972): Close Encounters of the First (no physical evidence), Second (physical traces), and Third Kinds (occupants observed).

The parallels to modern UFO sightings are eerie. For example, in 217 BC, numerous witnesses in Rome watched a group of “shiny round shields of polished bronze” moving across the sky. At the same time in the countryside east of Rome many people reported seeing mysterious “forms of men completely dressed in shining white.” Three years later, people in northern Italy saw something like a large white marble “altar in the sky” accompanied by human shapes clothed in brilliant white.

In 154 BC, more “flying shield-like disks” appeared. One night in 104 BC, people of two Italian towns watched as “flaming spears and oblong-shaped shields rushed at each other” in a kind of aerial “battle.” In 100 BC, a very large, round shield-shaped object traveled across the sky. In 91 BC, a huge fiery disk was accompanied by sonic boom-like sound. Later that same day, people in Spoleto watched a UFO’s vertical approach and take-off, as a great “gold-colored ball rolled down from the sky toward earth, then rose up again.” In 74 BC, thousands witnessed a large, flaming object of “molten silver” crash land between two armies on a Roman battlefield in Turkey. The object was shaped like a large storage jar with a pointed bottom, something like a nose-cone. In Rome, 43 BC, “a spectacle of missiles and weapons and shields was seen to rise from the horizon up to the sky, with a loud clashing noise.”

A Close Encounter of the Third Kind reported in AD 150, with a “spacecraft” hovering and landing, is uncannily similar to the 1977 Hollywood movie. On the main road from Rome to Capua, on a sunny day, an immense UFO about 100 feet across appeared overhead and moved downward. This object was flat and curved, like a huge “piece of pottery” or “potsherd.” The top of the object had “many colors” and shot out fiery rays of light. The UFO landed, raising a cloud of dust, and an occupant emerged, described as something like a “maiden clad in white.”

The astronomical meteorologist who analyzed these Roman reports in Classical Journal (2007) notes that the “UFO phenomenon, whatever it may be due to, has not changed much over two millennia”: disk, elongated, or sphere shapes; metallic, brilliant colors and materials; smooth, erratic, or hovering motions; the object often vanishes. Whether these are extraordinary atmospheric effects, astronomical phenomena, or extraterrestrial encounters, the persistence of consistent details over thousands of years seems to point to something real observed by many witnesses over time, something that we do not yet understand.

The astronomical meteorologist who analyzed these Roman reports in Classical Journal (2007) notes that the “UFO phenomenon, whatever it may be due to, has not changed much over two millennia”: disk, elongated, or sphere shapes; metallic, brilliant colors and materials; smooth, erratic, or hovering motions; the object often vanishes. Whether these are extraordinary atmospheric effects, astronomical phenomena, or extraterrestrial encounters, the persistence of consistent details over thousands of years seems to point to something real observed by many witnesses over time, something that we do not yet understand.

June 4, 2012

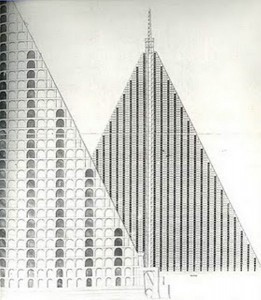

Thomas Willson’s Metropolitan Sepulchre

By Marri Lynn (W&M Regular Contributor)

Thomas Willson's pyramid blueprint.

Finding an affordable, respectable place to live in Georgian or Victorian London was ever a problem, and one which citizens could not escape even in death. Overpopulation of the city’s major graveyards caused public scandals due to sanitation issues, as well as regular olfactory affronts and a macabre mockery of Christian dignity. As a result, innovators soon rushed to address this problem by proposing new graveyard sites, and new internment schemes.

One such innovator was named Thomas Willson. He would prove to be perhaps a little too innovative for the aesthetic, moral, and economic tastes of the day.

To house London’s dead, Willson prepared a blueprint of what would come to be called the Metropolitan Sepulchre. In Willson’s creative vision, a huge pyramidical structure would be built upon Primrose Hill, in North London, with a base as large as Russell Square and a tip towering nearly four times higher than St. Paul’s cathedral, to dominate the skyline. The vast pyramid would be constructed of brick with granite facing, and would have quarters for a keeper, clerk, sexton, and superintendent, as well as its own office and chapel. At full capacity, the Sepulchre would eventually house 5 million bodies.

Historian N.B. Penny called it a “nightmarish combination of megalomaniacal Neo-Classicism and dehumanized Utilitarian efficiency.” But for Willson, the pyramid was to be a “coup d’oeil of sepulchral magnificence unequalled in this world.” And it was a dream very nearly realized.

The financing behind the Sepulchre was sound. A company named the Pyramid General Cemetery Company had been set up to engage investors and produce stock. Calculating the cost of the pyramid against the selling prices of the family vaults it would contain, which were to fill up at a rate of 40,000 bodies annually, Willson and his associates stood to regain the project’s cost and then some. Their calculated profit margin was just under £11 million.

Willson presented his Sepulchre to Parliament, hopeful that they would grant the necessary charters to rubber stamp the project. He pitched his idea at the same time as an Inner Temple barrister named George Frederick Carden, who proposed a cemetery reminiscent of the garden-graveyards being produced by Père Lachaise in France. Willson allegedly withdrew his appeal before a Parliamentary verdict, in order to give opportunity to Carden, who was a co-worker at the General Cemetery Company.

The project lived on, albeit languishing in a mire of postponements and bad press. In 1828, the Literary Gazette called it ridiculous, a “monstrous piece of folly.” Plans and a small model remained on display at the National Repository at Charing Cross for two years, and eventually the Sepulchre received more friendly reportage. And at last, Willson’s proposal received the sincerest form of flattery: imitation, or rather, complete replication, by an architect in Paris.

Willson soon accused George Frederick Carden of intellectual theft, and published letters in John Bull to that effect. Carden responded by suing Willson for libel. It ended in public embarrassment for Willson, who was forced to pay libel damages and issue a public letter of apology, confessing to having written his letter in a fit of pique. Carden had taken the moral high ground by forgiving Willson, and came out of the affair clean.

The last whiff of Willson’s floundering pyramid scheme appears in the Great Exhibition of 1851, wherein a model of the ‘Great Victoria Pyramid’ attributed to a J. Willson or T. Willson was put on display. Willson had downsized his dream from an 18-acre megastructure to a more palatable 5-acre pyramid meant to house 625,000 bodies instead of 5 million. Willson’s affection for his project did not diminish, though after the Great Exhibition the public interest in entertaining thoughts of his curious Sepulchre sharply waned.

Imagine what a different place London would be, overlooked by the granite façade of the Metropolitan Sepulchre. Imagine, too, what work would keep historians of medicine and forensic anthropologists combing through its chambers of 5 million bodies. The pastoral landscapes of the garden cemeteries that were built instead may be less thrilling to behold and explore, but nevertheless they enjoy their own quiet victory over our urban landscapes.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently studying French, while freelancing as a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

May 31, 2012

The Puppy Water and Other Early Modern Canine Recipes

At first I thought it was a joke when I read a recipe for “The Puppy Water” in a recipe collection compiled by one Mary Doggett in 1682. “Take one Young fatt puppy and put him into a flatt Still Quartered Gutts and all ye Skin upon him”, then distill it along with buttermilk, white wine, pared lemons, herbs, camphire, venus turpentine, red rosewater, fasting spittle, and eighteen pippins.

Although Mary Doggett’s recipe does not specify purpose, puppy water was a facial treatment – as immortalized by Jonathan Swift in his poem, “The Lady’s Dressing Room” (1732):

There Night-gloves made of Tripsy’s Hide,

Bequeath’d by Tripsy when she dy’d,

With Puppy Water, Beauty’s Help

Distill’d from Tripsy‘s darling Whelp.

Swift also, however, refers to another canine usage: gloves made from dog’s hide. As noted in Nicholas Culpeper’s Pharmacopoeia Londinensis (1718), “little puppy dogs” (and various other animals, such as hedge-hogs, snails, foxes, moles, frogs, or earthworms) “may be made beneficial to your sick bodies”. Robert James’s entry for “Canis” in his Medicinal Dictionary (1743-5) explained that Europeans “generally abstain from Dogs Flesh, till Necessity… obliges them to use it.” But use it they did: the flesh, fat, skin and excrement could all be incorporated into medicines recommended even by renowned medical practitioners.

Saint Roch: The story goes that a dog saved Roch from the plague by licking his wounds. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

These remedies ranged from the foul: Culpeper’s Oleum Catellorum (Oil of Whelps) “to bath the Limbs and Muscles that have been weakened by wounds or bruises” or George Bate’s gargle for mouth ulcers and thrush that included a white dog turd (Pharmacopoeia Bateana, 1706). To the cruel: Philip Woodman suggested cutting a live puppy lengthwise through the middle and applying it hot to the head to treat a frenzy (Medicus Novissimus, 1712). To the comforting: for iliac passion (intestinal obstruction), Thomas Sydenham instructed that a live puppy should be laid to the patient’s naked belly for two or three days (Praxis Medica, 1707).

James’ dictionary entry explained the rationale for these treatments. For example, keeping a warm puppy next to one’s colicky belly or gouty leg provided “kindly and cherishing Heat”, but it also worked sympathetically by transferring the disease into the animal instead.* Having a dog lick one’s wounds and ulcers could cure them more quickly. The fat of the dog was thought to be better externally than any other animal fat, owing to its penetrating quality, and the drippings could be eaten to treat lung problems or epilepsy. Turned into gloves, the skin of the dog would reflect summer sun; as a piece of leather, it could protect gouty or arthritic legs from cold. Dog dung, being hot and acrid, might treat internal bleeding or toothache.

James did not mention “The Puppy Water” itself. However, for that we might look to the ancient Greeks whom he did discuss. According to Hippocrates, “the Flesh of Dogs is of a heating, drying, and corroborating Nature… whereas that of whelps is of a moistening, lubricating Quality.” The other ingredients in the recipe point to a similar use as the puppy: pippins were moistening and good against inflammation; fumitory and agrimony treated diseases of Saturn (such as old age) and were strengthening and cleansing; plantain firmed the sinews and helped skin problems. Just the thing for a face wash!

*The evidence for this is dubious. James recounted the case of a patient in 1742 being salivated (by mercury). When a visitor arrived, the patient put aside his basin filled with his saliva, which his dog proceeded to drink. Within ten hours, the dog suffered from convulsions and died.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

May 23, 2012

Helen King on Gladiators, Midwives, Traveling Vulvas, and Vibrators

Our very own Helen King did several fantastic interviews for Open University, where she is Professor of Classics. For those of you who are fans of Helen’s work (I’m raising my hand high!), have a look at the videos.

Our very own Helen King did several fantastic interviews for Open University, where she is Professor of Classics. For those of you who are fans of Helen’s work (I’m raising my hand high!), have a look at the videos.

And if you haven’t had a chance to look at her most recent–and hilariously fascinating–post on medieval vulva badges, it’s not to be missed! And Helen’s been on a roll (or dare I say it, buzz) lately with this Atlantic article on the history of vibrators. Who says historians don’t have fun?

Come on girls, let’s get those vulvas traveling!

May 22, 2012

The Senator, the Scientist and a Country Worth Defending

By Marc Merlin

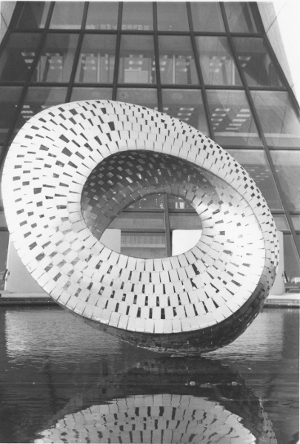

Mobius Strip, a sculpture by Robert Wilson at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Marc Merlin, 1976)

It was April 17, 1969, Richard Nixon was three months into his first term as President of the United States, the homes of the inner-city were crumbling, the Vietnam War was raging and $250 million was still a whole lot of money.

$250 million was the price tag attached to the construction of what was to be the largest atom smasher in the world, a particle accelerator consisting of a ring of magnets 4 miles in circumference to be situated in a tunnel a few dozen feet beneath the surface of restored Illinois prairie west of Chicago, designed to send protons flying around in a circle at near the speed of light.

It was the job of John O. Pastore, Senator from Rhode Island and Vice Chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, at the AEC hearing that day to find out exactly what good could be accomplished with such an expensive machine, because it would be his responsibility to “carry the ball” as a request to the Appropriations Committee, itself troubled by other pressing concerns such as “feeding the hungry and clothing the naked.” The senator, needless to say, wanted to find a practical peg upon which to hang his fiscal hat.

With mounting frustration Pastore continued his questioning that afternoon with a second witness, Robert R. Wilson, the director of the proposed facility that would one day be known as Fermilab. The Cold War being what it was and funding of competition with the Soviet Union requiring scant justification, Pastore decided to explore what he no doubt thought would be a promising new line of inquiry.

Senator Pastore: Is there anything connected in the hopes of this accelerator that in any way involves the security of the country?

Dr. Wilson: No, sir; I do not believe so.

Senator Pastore: Nothing at all?

Dr. Wilson: Nothing at all.

Robert Wilson, it turns out, was no stranger to the morally fraught intersection of military necessity and scientific progress. A Wunderkind of cyclotron physics in the 1930s, as the youngest group leader in the experimental division of the Manhattan Project, Wilson had stoked the ire of General Leslie Groves, the Army commander in charge of that effort, with his suggestion that their work on the atomic bomb might end with the defeat of Nazi Germany. That episode marked the beginning of Wilson’s life as an advocate for a public policy fully informed by knowledge of potential dangers posed by advances in science.

But Robert Wilson was also by avocation an artist and an architect and, as Senator Pastore pressed his point, Wilson made his own perspective clear.

Senator Pastore: Is there anything here that projects us in a position of being competitive with the Russians, with regard to this race?

Dr. Wilson: Only from a long-range point of view, of developing technology. Otherwise, it has to do with: Are we good painters, good sculptors, great poets? I mean all the things that we really venerate and honor in our country and are patriotic about. In that sense, this new knowledge has all to do with honor and country but it has nothing to do directly with defending our country except to help make it worth defending.

Whether or not this was the answer that Senator Pastore wanted to hear, it was apparently enough of a ball for him to carry to the Appropriations Committee to persuade them to cut Wilson a $250 million check. Operations of at the National Accelerator Laboratory began under Wilson’s direction in June 1972, on time and under budget.

I was fortunate enough to meet Robert Wilson while I was a graduate student working at Fermilab in 1976 and 1977. In a place where it was not uncommon to see a Nobel laureate or two having lunch in the cafeteria on any given afternoon, Wilson commanded a special kind of reverence. As time has passed I have come to understand better and better why.

Marc Merlin is a full-time science advocate and Director of the Atlanta Science Tavern. He writes occasionally about film, politics and, yes, science on his blog, Thoughts Arise .

May 20, 2012

Celebrate! BLOOD WORK paperback release

Time to celebrate! The paperback of Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution is now out in paperback. And with a fancy new cover to boot!

Time to celebrate! The paperback of Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution is now out in paperback. And with a fancy new cover to boot!

My wonderful publisher, W.W. Norton, is offering up giveaway copies through Wonders & Marvels, Twitter, and Good Reads. Details below. Note: copies can be sent only within the US.

Signed copy anyone?

Parnassus Books, Ann Patchett’s beloved local bookstore in my hometown, can ship signed or personalized copies. Just shoot them an email to make arrangements. (Nashville folks, I’m doing an event there Wednesday night, May 23. See you there?)

Blood Work is a fantastic gift for friends/family members who love page-turning murder mysteries and narrative history. Recently, I’ve been signing lots of copies as gifts for doctors, medical students, and pre-meds too.

So back to those GIVEAWAY COPIES:

To enter via Twitter: Simply retweet one of my @history_geek tweets this week about Blood Work or tweet something else about the book. Be sure to include @history_geek in the tweet so I see it. Once a day at 4pm CST, I’ll announce a winner selected at random. You can enter up to 5 times for each daily giveaway…and remember it’s most helpful to tweet at different times of the day!

To enter via Good Reads: Between May 21-25, W.W. Norton is doing a big giveaway at Good Reads. Just head here to enter.

To enter via Wonders & Marvels: Easy as pie! Leave a comment on this post with a question about the book, writerly experiences, or anything you’re curious about AND/OR one thing you’d be happy to do or have done to help spread the word about the paperback release.

On Friday, I’ll select the winners at random and announce them here. Some ideas of what you can do to help get the word out:

Post something on your own blog about Blood Work (I’ll collect the URL’s and give some W&M blog love later in the week)

Send emails to friends to tell them about the book and this giveaway

Call your local bookstore to make sure they’re stocking the book

Order a signed/personalized copy of Blood Work from Parnassus Books (while entering to win a copy for a friend)

Talk your book group into reading Blood Work for an upcoming meeting (I love doing Skype chats with book groups, by the way.)

Good luck! But especially, THANK YOU for reading!

All my best,

Holly

Cool Vikings

Some cool facts about Vikings:

Investigation of mitochondrial DNA shows that about 70% of the women in modern Iceland are descended from Irish women, but few Icelandic men are descended from Irish men. The most likely explanation for this is that when the Vikings pillaged Ireland, they killed the men and took the women home with them.

The Vikings invented the amphibious landing vessel. Their ships could be sailed straight up on shore.

The Vikings didn’t have compasses, but they could tell roughly where north was. Supposedly, if you put fleas in a box, they’ll jump northward. I don’t know if this is true, and I’m not planning to make the experiment!

Most people have heard of the Viking torture called the “blood eagle.” This is where a captured enemy’s ribs would be severed from his spine, his lungs pulled out, and salt sprinkled on the wound. People would stand around and jeer at the victim and his fluttering lungs (the “eagle’s wings”) as he slowly expired. Alas for those who love bloodthirsty stories, this probably didn’t happen—you’d be dead from blood loss and/or shock by the time the lungs were exposed, and you can’t breathe with your lungs outside your body (you need the diaphragm to move the air in and out). This is probably a misunderstanding of poets’ saying something about fallen warriors having their backs carved by the blood eagle, meaning they were clawed by carrion birds after they died.

Some skeletons of Viking men show horizontal grooves filed in their teeth. The only other people known to have done this are Native Americans from the Great Lakes region. Hmmm.

Gudrid, the mother of the first baby of European origin known to have been born in America, was born in Iceland, traveled to Greenland with Eric the Red (her father-in-law), and then got shipwrecked attempting to go to “Vinland.” She was rescued (by her brother-in-law Leif Ericsson), and went back to Greenland. She then made a successful trip to America and stayed there a year and a half or so, during which her son Snorri was born. Then back to Greenland. She became a Christian and traveled to Rome. She went back to Greenland where she lived out her days as a nun. She was known as “Gudrid the Far-Traveler.”

One source says that Vikings in Canada used jasper to start fires. I can’t find out how, though.

The Icelanders of the Viking era didn’t have a central leader, but local chieftains. Once a year all the free males gathered for a General Assembly and voted on everything. Trials were held in smaller assemblies and decisions were made by 36 judges, who acted something like a jury.

There were no honey-bees on Iceland, meaning they had to import mead, the fermented honey drink that they loved.

Vikings didn’t wear horned helmets. But you knew this already, didn’t you?