Holly Tucker's Blog, page 85

February 23, 2012

What makes good historical TV?

A local archaeologist with the Baldock skeleton

By Helen King (W&M Regular Contributor)

How do you like your history on television? Do you like to hear from 'talking heads', or would you rather see a docudrama recreating a scene from the past? Do you get a bit fed up with the standard scene in which the presenter turns up at a museum or a library to 'meet' the expert who just happens to be hanging around there surrounded by conveniently relevant artifacts?

I made several brief appearances on TV last year. My favourite was on BBC's History Cold Case. The case was a Romano-British woman who was buried with three newborn babies – two of which, the DNA eventually showed, were definitely her children. We couldn't be certain about the third.

My role, as 'expert', was to talk to the presenter about how difficult births were handled in earlier historical periods, using ancient Greek texts that were known in the Roman world, but also analogies with 18th c methods. That part was filmed at the Royal College of Obst and Gyn. The production company was looking for a venue, and I have worked with the Library there before and knew that they are keen to participate in programmes like this. The Library staff did us proud – they produced various worrying devices from their historical collection, with a fine array of hooks and so on, as well as rare books on how such devices were used in the 18th century. The production company wanted to film a section with the 'expert' saying 'And if you come this way, there's something I think you'd like…' I had no idea what to offer for this section, but the RCOG turns out to have some wonderful 16th c books which even showed the position of triplets in the womb. So, we filmed that – the best bit, I reckoned, as it showed exactly the same positions as the 21st c expert obstetrician talked about later in the programme – but it was lost on the cutting room floor! My second appearance in this programme was in a cold field in Baldock, where the skeletal remains were displayed in a tent while the forensic team talked through their conclusions. Most worrying moment – a close tie between a local dog getting in and expressing an interest in the bones, and a member of the local Archaeological Society swishing her coat against the table and knocking the foot bones on to the floor. Gasps of horror until they were put back in place!

There was something very moving and exciting about being in the presence of the skeletons of the woman and her babies after discussing them in the abstract. All credit to the archaeologists who had realised these tiny bones could be part of a baby. Part of the show's format is a facial reconstruction, and like the members of the local archaeological society who were present I had not seen this until it was projected on a screen in the tent. My dropped jaw was genuine! I felt I had learned a lot. That's when doing TV is really fun!

February 22, 2012

Dissecting the Living: Vivisection in Early Modern England

A physiological demonstration with vivisection of a dog. Oil painting by Emile-Edouard Mouchy, 1832. From the Wellcome Library, London.

In 1664, Robert Hooke—a pioneering member of the Royal Society and lead scientific thinker of his day—decided to investigate the mechanisms involved in breathing. In his laboratory, he strapped a stray dog to his table. Then, taking his scalpel, he proceeded to slice the terrified animal's chest off so he could peer inside the thoracic cavity.

What Hooke hadn't realised before he began his experiment was that lungs were not muscles, and that by removing the animal's chest, he had removed the dog's ability to breathe on its own. To keep the animal alive, Hooke pushed a hollow cane down the dog's throat and into its windpipe. He then pumped air into the animal's lungs with a bellow for over an hour, carefully studying the way in which the organs expanded and contracted with each artificial breath. All-the-while, the dog stared at him in horror, unable to whimper or cry out in agony.

On 10 November 1664, Hooke wrote to Robert Boyle about his experiment. In his letter, he described how he 'opened the thorax, and cut off all the ribs' of the dog, and 'handled…all the other parts of its body, as I pleased'. But despite these rather horrific details, we see through Hooke's words a man deeply moved by the suffering he had caused, for he ends, 'I shall hardly be induced to make any further trials of this kind, because of the torture of this creature'. [1]

The term 'vivisection', which refers to the act of dissecting a live animal or human being, was coined in 1709. Yet, it celebrated a long tradition reaching back thousands of years. One of the earliest recorded accounts dates from 500 B.C., when Alcmaeon of Croton severed the optic nerves of live animals in order to understand how it affected their vision. Indeed, William Harvey's discovery of the circulation of blood around the heart in 1628 was made possible by his use of vivisection; and it is likely that it was Harvey's work which prompted Hooke to conduct his own experiments several decades later.

Hooke may have abstained from further vivisections after seeing the anguish he caused in the dog, but others were not necessarily willing to abandon these types of experiments simply because animals suffered as a result. [2]

In particular, surgeons-in-training found vivisection a helpful tool for learning how to operate quickly and confidently. In a pre-anesthetic era, the slightest hesitation could cause a patient to die from shock and blood loss. Working on the bodies of live animals allowed the inexperienced surgeon to operate at his own pace, learning from his mistakes as he went without the fear of accidentally killing another human being. In early modern England, where bear-baiting and cock-fighting were national pastimes like football or rugby are today, it was perfectly acceptable to allow for such extreme suffering in animals under these conditions.

That is not to say, however, that there were no objections to vivisection during this period. Most protests, though, were not centered on animal cruelty, but rather the argument that animals and humans differed too much anatomically for vivisection to be useful. Still, there were those who spoke up in defense of animals.

In 1718, the poet Alexander Pope—a renowned dog lover—condemned the experiments of his neighbour, Reverend Stephen Hales, who often cut open the abdomens of stray dogs while investigating the rise and fall of blood pressure. While conversing with his friend, Joseph Spence, Pope reportedly said of Hale: 'He commits most of these barbarities with the thought of its being of use to man. But how do we know that we have a right to kill creatures that we are so little above as dogs, for our curiosity, or even for some use to us?' [3]

Similarly, Samuel Johnson—essayist and author of A Dictionary of the English Language—spoke out against vivisection in the Idler (August, 1758). He condemned the 'race of wretches, whose lives are only carried by varieties of cruelty' and whose 'favourite amusement is to nail dogs to tables and open them alive'.

The image of a live dog being nailed to a table may seem an exaggeration on the part of Johnson to elicit feelings of disgust and horror. Sadly, this is not the case, as evidenced by the testimony of Mr Richard Martin, who moved to bring a bill for the repression of bear-baiting and other forms of cruelty to animals, to the Irish House of Commons in 1825:

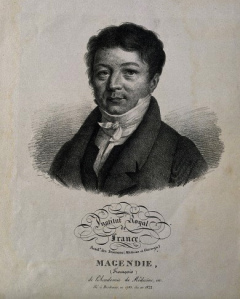

There was a Frenchman by the name of Magendie… [who] at one of his anatomical theatres, exhibited a series of experiments so atrocious as almost to shock belief. This M. Magendie got a lady's greyhound…nailed its front, and then its hind paws with the bluntest spikes that he could find, giving as reason that the poor beast, in its agony, might tear away from the spikes if they were at all sharp or cutting. He then doubled up its long ears, and nailed them down with similar spikes…He then made a gash down the middle of the face, and proceeded to dissect all the nerves on one side of it…. After he had finished these operations, this surgical butcher then turned to the spectators, and said: `I have now finished my operations on one side of this dog's head, and I shall reserve the other side till to-morrow. If the servant takes care of him for the night, I am of the opinion that I shall be able to continue my operations upon him to-morrow with as much satisfaction to us all as I have done to-day; but if not, ALTHOUGH HE MAY HAVE LOST THE VIVACITY HE HAS SHOWN TO-DAY, I shall have the opportunity of cutting him up alive, and showing you the motion of the heart. [4]

Stories, such as these, are very disturbing, and illustrate that some medical men took pleasure in such sadistic practices. Nonetheless, as illustrated in Hooke's letter to Boyle, it would be wrong to assume that all those who performed vivisections during this period were calculating and heartless.

Most importantly, however, we must remember that many ground-breaking discoveries were made as a result of vivisections, and it is to these animals we owe a huge debt for advancements made in medical science during the early modern period.

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon's Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

1. Letter from Robert Hooke to Robert Boyle (10 Nov 1664). In M. Hunter, A. Clericuzio and L. M. Principe (eds.), The Correspondence of Robert Boyle (2001), vol. 2, p. 399.

3. Hooke did not perform any further vivisections per se; however, he did continue to use animals in his experiments.

3. Cf. Joseph Spence, Observations, anecdotes, and characters of books and men collected from conversation, ed. James M. Osborn (Oxford, 1966), vol. 1, p. 118.

4. Qtd from Albert Leffingwell, An Ethical Problem, or, Sidelights upon Scientific Experimentation on Man and Animals (London, 1916).

February 20, 2012

Medieval Metafiction

by Tracy Barrett, W&M contributor

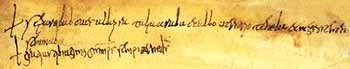

In 1924, the linguist Luigi Schiapparelli discovered some lines in the margin of a religious text, scribbled in a Veronese hand in the late eighth or early ninth century, probably to test the scribe's newly cut pen. They read:

Se pareba boves He led oxen

alba pratalia araba he plowed white fields

& albo versorio teneba and he held a white plow

& negro semen seminaba and sowed black seed

Linguists immediately declared this one of the earliest examples of written Italian—so early that some call it late Latin, and not Italian at all.

In 1924, Italy was at the height of its fascist era, when the peninsula's glorious past was being held up as a model for the Italian people. Italian scholars rhapsodized about the hearty farmer who is eager to plow his field despite the frost covering it. (The white plow was glossed over.)

It wasn't until a linguistics professor was discussing these lines in a class that a young student told him that the text wasn't a poem about a virtuous farmer at all, but was a riddle that her grandmother had told her. The oxen are fingers, the white fields are paper (or parchment), the white plow is a white quill pen, and the seeds are the ink.

Lately, I've been pondering metafiction—that literary convention where an author reminds you that you're reading a book. It's usually considered a sophisticated postmodern technique, but it's prevalent in children's literature, for example in the recent It's a Book and The Neverending Story. You might have noticed metafiction in Jane Eyre ("Reader, I married him"), Don Quixote (where the second part reflects on the first part), The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, many books by Italo Calvino.

Isn't it wonderful that at the dawn of Italian language, whose literature has always pushed the envelope of literary styling, a scribe testing his new pen left us this self-referential scribble?

February 19, 2012

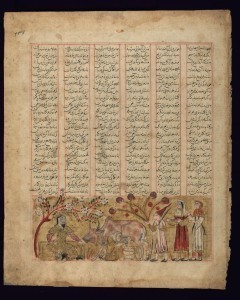

The Art of the Book

By Pamela Toler

Image courtesy of the Walters Art Museum

The Islamic world created illuminated manuscripts that rivaled anything that came out of a medieval monastery: Qu'rans, historical chronicles, stories of the prophets, the deeds of kings, lyric poetry, heroic epics, philosophy, scientific treatises, and romantic tales.

Caliphs, courtiers, and wealthy merchants commissioned manuscripts from the ninth century until well into the seventeenth century, when the Islamic world reluctantly accepted the value of Mr. Gutenberg's printing press. Each manuscript was an expensive and unique production that required the talents of many artists: craftsman who ruled the pages, calligraphers, painters, illuminators, bookbinders and chest makers.

Each page was designed with a ruled frame that determined the number of lines of text on the page and the size and location of paintings, chapter headings, texts and borders. The modern viewer focuses on the miniatures, wonderfully detailed paintings often no larger than a sheet of notebook paper. For the original audience, the paintings are second to the quality of the calligraphy. As sixteenth Iranian author Qadi Ahmad put it, "If someone, whether he can read or not, sees good writing, he likes to enjoy the sight of it." Calligraphers were not anonymous copyists, but revered artists who learned at the hand of a master.

Unlike books in English, where there are many fonts but only one script, Islamic calligraphers had many scripts to chose from, each with a different graphic and emotional quality. They could be slanted or rounded, upright or "hanging", angular or cursive. Some were designed to be easily read, others to be decorative. Qu'rans were often written in one of the angular kufic scripts. One script was described as the "bride of calligraphic styles" and was generally used for lyric poetry and romantic tales.

You've got to wonder what the producers of these works would think about the modern paperback.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

February 17, 2012

Contributor Q & A: Christopher Long

Christopher P. Long

As editor of Wonders & Marvels, I have the pleasure of introducing our monthly regular contributors.

On the docket today is Christopher P. Long…

Holly Tucker: We have historians, literary scholars, and novelists among our regular contributors at Wonders & Marvels. Thanks to you, we can now add "philosopher" to the list. Could you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Christopher P. Long: I am an Associate Professor of Philosophy (going up for full this year!) at the Pennsylvania State University where my research focuses on Ancient Greek Philosophy. I have written two books on Aristotle (The Ethics Of Ontology and Aristotle on the Nature of Truth

and Aristotle on the Nature of Truth ) and I am currently finishing up a book on Platonic and Socratic Politics. In January 2010, in addition to my faculty responsibilities, I took on more administrative responsibilities as the Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies in the College of the Liberal Arts at Penn State. As Associate Dean, I have sought to use social media to cultivate a community of education in the College in which the undergraduate experience is celebrated. At the center of that effort is our Liberal Arts Undergraduate Studies blog, which is a curated space for students to write about and reflect on their undergraduate experience at Penn State. Most importantly, though, I am a husband and the father of two amazing little, but very quickly growing, girls.

) and I am currently finishing up a book on Platonic and Socratic Politics. In January 2010, in addition to my faculty responsibilities, I took on more administrative responsibilities as the Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies in the College of the Liberal Arts at Penn State. As Associate Dean, I have sought to use social media to cultivate a community of education in the College in which the undergraduate experience is celebrated. At the center of that effort is our Liberal Arts Undergraduate Studies blog, which is a curated space for students to write about and reflect on their undergraduate experience at Penn State. Most importantly, though, I am a husband and the father of two amazing little, but very quickly growing, girls.

HT: When we met for the first time at HASTAC, I was really impressed by how you balance serious scholarship with teaching. Much of this teaching happens outside of the classroom through the podcasts you do. What has this contributed to your work?

CpL: In the Summer of 2009, I became a Faculty Fellow at Penn State's Educational Technology Services during which time I pursued a project called Socratic Politics in Digital Dialogue. The idea was to use social media to enhance my academic scholarship. I have come to think of this as technologically enriched scholarship. During that summer, I created a podcast called The Digital Dialogue in an attempt to cultivate a community of scholarship around my research into the way Socrates practices politics in the Platonic dialogues. I wanted to explore the possibility of pursuing rigorous academic philosophical research and teaching using digital media technologies as opposed to studying the impact of those technologies on my work. I have now produced over 50 episodes of the Digital Dialogue. These conversations with colleagues at Penn State and around the country have enriched in unanticipated ways the book I am in the process of completing.

I learned how to use social media to cultivate a community of learning around specific themes in direct collaboration with students in my teaching. In the classroom, I have tried to develop a cooperative style of education that takes advantage of the affordances technologies offer us to collaborate with our students in ever more public and dynamic ways. I have written about that in an article on Cooperative Education in Teaching Philosophy.

HT: So this is a website about the past, so I always end with this: If you could travel back in time, where would you go? What question do you have about the past that you would try to get answered?

CpL: I would travel back to Athens in 399 BCE, around the time of Socrates' trial and death. Scholars have long speculated about the political circumstances that led to the trial of Socrates and the decision ultimately to put him to death. My stay there, however, would focus less on the historical details of the trial than on the general mood of the time. In fact, it would be tremendously insightful just to feel what it was like to live there at that time, to talk to people about their prosaic concerns and to experience the quotidian life of an Ancient Greek citizen of Athens. A more detailed sense for the everyday in ancient Athens would add enormous depth to my ongoing philosophical engagement with the ideas that gained currency at that time, and continue to influence us today.

References

Long, Christopher P. "Cultivating Communities of Learning with Digital Media: Cooperative Education through Blogging and Podcasting," Teaching Philosophy 33, 4 (2010): 347-361.

February 15, 2012

Fear of flute girls

Phobias go back a long way. They are fears that can be very debilitating, and although sufferers know that the fear is irrational and excessive, the phobia can be very difficult to overcome. Sometimes phobias seem to have been constant over time. An example would be gephyrophobia, 'fear of bridges'; yes, the Greeks had a word for it, and this label simply means, er, 'fear of bridges'! This is found today and featured in a BBC TV series of the 1990s, GBH, where the character played by Michael Palin was a sufferer.

Phobias go back a long way. They are fears that can be very debilitating, and although sufferers know that the fear is irrational and excessive, the phobia can be very difficult to overcome. Sometimes phobias seem to have been constant over time. An example would be gephyrophobia, 'fear of bridges'; yes, the Greeks had a word for it, and this label simply means, er, 'fear of bridges'! This is found today and featured in a BBC TV series of the 1990s, GBH, where the character played by Michael Palin was a sufferer.

But the condition also features in the ancient Greek collection of case histories, Epidemics, traditionally associated with the name of Hippocrates and dating back to the fourth century BC. The sufferer was called Democles and he had panic symptoms so bad that, even if the bridge was not very high – just over a ditch – he had to get off and walk through the ditch instead.

When Democles turned up to see the physician who recorded his story, he came with a friend, Nicanor. Nicanor had a rather less common phobia – fear of flute girls. When he was at a symposium – an all-male Greek drinking party for around 14-30 men – and he heard the flute girl start to play, he became ill. No explanation is given in the original text for this, but perhaps we can make some guesses.

Flute girls were part of the entertainment at these parties. The partygoers were expected to drink, to discuss the meaning of life, to make up poems and songs, and also to have sex with the entertainers. There was plenty of opportunity to lose face in front of your friends and peers. The flute girl started to play when the drinking began. Her instrument, the aulos, was more like a bassoon in terms of how it is played. The Greeks associated it with madness, and loss of self-control.

Perhaps Nicanor had had a bad experience with a flute girl, and the music brought it all back. Perhaps the whole competitive male context of the symposium was just too much for him. Or perhaps he expected the music to send him mad – and it did.

On the symposium, see Oswyn Murray (ed.), Sympotica. A symposium on the symposion (Oxford, 1990)

If you want to hear an aulos (be careful!) you can hear its sound on http://www.oeaw.ac.at/kal/agm/

Image: wikimedia commons: attributed to the Brygos Painter

_

February 14, 2012

Man's Best Friend: Dogs in Pharaonic Egypt

by Annie Shanley (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

Dogs were popular pets in ancient Egypt and were the objects of genuine affection by kings, nobles, and laborers. While not all ancient animals were given names, over 75 dog names have been identified and usually refer to the color or character of the dog. That owners cared for their dogs in this life is apparent by the veterinary papyri uncovered from ancient Egypt. Pets also shared in the afterlife with their owners as evident by their inclusion in tomb scenes and human burials.

Tomb relief, 5th Dynasty, c.2465-2323 BCE. Limestone. MCCM 2006.10.1. Gift of Wayne and Ellen Bailey to the Michael C. Carlos Museum. Photo by Annie Shanley

When looking at depictions of dogs in ancient Egyptian art, scholars and general audiences are eager to determine what type of dog is being shown. Beginning in the Predynastic Period (c. 4000 BCE) the most commonly portrayed dog is a type of hunting hound with erect pointed ears and a short curly tail. This dog is often referred to as a Pharaoh Hound, an Ibizan Hound, or a Basenji.

But what about the actual remains of dogs? Bones recovered from archaeological sites have not been subjected to systematic studies, but those bones that have been examined belong to mutts. Recent DNA research into modern dog breeds may help point us in the right direction. Based on preliminary findings, the Basenji can be positively classified as an "ancient dog breed", while the Pharaoh Hound and Ibizan appear to be more modern breeds. The Pharaoh Hound originates from Malta, and the name was given to the breed during the 1920's because they look like the dogs in Egyptian art. The Ibizan Hound was first identified on the island of Ibiza off the coast of Spain. While it is true that more comprehensive DNA testing needs to be conducted, and the impact of selective breeding needs to be taken in to account as well, DNA science does offer exciting possibilities for identifying ancient Egyptian man's best friend.

Annie Shanley is a doctoral student in the Art History Department at Emory University. Her research interests include the material culture and technology of Egypt, the Near East, and the ancient Mediterranean, Egyptian texts, and ancient trade. Annie's current work focuses on glass and faience in Egyptian and Hittite texts.

February 12, 2012

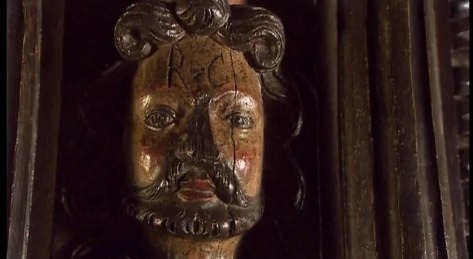

The Secret History of The Great Bed of Ware

By Beth Dunn

Lovers have been carving their initials into tree trunks and fenceposts since time immemorial. It seems like if you're in love, you're a fool if you don't carry a pocket knife at all times, just so that you can proclaim your passion to the world.

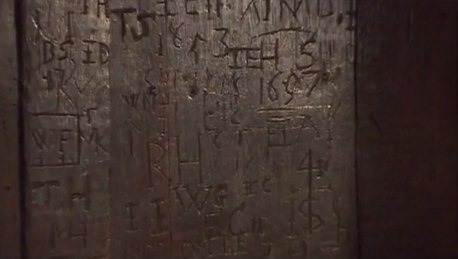

Maybe this is why the biggest bed in Christendom is simply riddled with graffiti.

I mean, maybe folks just like carving their names in stuff. But I bet there's more to it than that.

The Great Bed of Ware has been a tourist attraction for a very long time, and it's hard to say if most of its carved initials are the result of over-excited tourists marking their passage along the great road north out of London, or if some are actually the remnants of a night of passion in a provincial inn in Hertfordshire. Built in the late 16th century and known to have graced the rooms of several different public inns in the English town of Ware, this staggeringly large and delightfully ornate bed has been sought out by the curious and the coital for hundreds of years.

The bed can now be found in the British Galleries of the wonderful Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where you can get right up close and marvel at its immense girth and vasty depths. It really is massive, even by today's standards. And you can see why it ranked among the top must-see sights in the itineraries of generations of British travelers.

As an item of antiquity, it's appeared in some pretty impressive footnotes. Shakespeare mentioned it in Twelfth Night. Byron mentioned it in Don Juan.

As a piece of furniture, it practically ranks as sculpture rather than utilitarian object. It's almost 12 feet square, anchored by two massive carved posts at the foot, and balanced by an equally overwrought headboard. But people can — and did — sleep in it. Sometimes it was booked to accomodate as many as twelve people at once, although frankly this seems to have been more in the way of a prank or a dare than anything else. Sort of the Elizabethan equivalent of seeing how many coeds you can stuff into a phone booth, if you get my drift.

But that graffiti? It's everywhere.

On the finely carved figures.

Among the carefully wrought marquetry.

Alongside the swans, for which the town of Ware was evidently renowned.

All crammed together, like coeds in a phone booth.

And while graffiti of this sort can be seen on museum pieces of all kinds, from medieval choir pews to ancient Roman frescoes, I'd like to think that at least some of the graffiti on the Great Bed of Ware served a more intimate purpose.

Surely at least some of these initials were carved in a moment of celebration, of giddy excitement or satisfied bliss. Surely some of these marks are the silent relics of two actual, living people, who spent an actual, living night with each other in a bed bigger than any bed they'd ever seen before. A bed that seemed tailor-made for lovers whose love was vast, and for whom the years ahead seemed endless and filled with promise.

A bed whose creaking frame still spells out their names, if you know where to look.

In code, yes. And nearly drowned out by all the sly chuckles and crude jokes of the tourists who all but crowd our lovers' names out of view.

But they're still there, just the same. Because some things truly never change.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, and can be found haunting the corridors of the Victoria & Albert Museum whenever she visits London. Which is, as you can imagine, not nearly often enough.

February 10, 2012

Why we love to read novels about queens: Part I

Do readers never tire of reading about queens? What is the great fascination?

I decided to ask some novelists, readers, bloggers, and experts.

I met Sarah Johnson, the author of Historical Fiction II: A Guide to the Genre and compiler of the blog Reading the Past (http://www.readingthepast.com), at the semi-annual Historical Novel Society U.S. conference. She told me, "It's safe to say that the fascination for such novels has been ongoing for some time. Dumas was writing novels about Marguerite de Valois and Marie Antoinette in the 1840s and '50s, for instance, and he wasn't the first. The trend comes and goes, and now it's firmly on the upswing with novelists such as Jean Plaidy, Norah Lofts, Margaret George, and Philippa Gregory and many gifted others." (Sarah believes perhaps a few dozen such novels were published in 2011.)

But why do we want to read about queens? Sandra Gulland, author of the magical trilogy about Josephine Bonaparte (the empress) and Mistress of the Sun (mistress of Louis XIV), answered, "I think we simply are hungry for stories of women in a position of power, because it's so rare. Some handle it gracefully (i.e. Josephine Bonaparte), and others wilt in the harsh glare of such light (Louise de la Vallière)." Sarah Johnson replied, "The majority of novels about queens take place in eras (12th through 18th centuries) when women had little say in the major decisions affecting their lives, but most queens, whether they were rulers themselves or consorts, had a wide sphere of influence. Plus, these women were served the finest cuisine, wore the most expensive gowns, had the most talented artists and musicians around them… and readers love descriptions of court life. (This is assuming the queens didn't end up in the Tower or its international equivalent!")

Novelist C.W. (Christopher) Gortner told me, "I think we are fascinated both by the queens' celebrity appeal as well as their fragility. Their lives, while outwardly glamorous, were full of trials and tribulations, tragedies and triumphs: we know that they struggled to survive. Their fragility and courage exert a powerful effect on our imaginations. The issues they faced were monumental."

He added, "I first became enamoured of historical fiction in my pre-adolescent years, when my mother gave me a copy of Immortal Queen, a novel about Mary of Scots, for my birthday. We lived in southern Spain; a ruined castle that had once belonged to Isabella of Castile sat near the beach by our flat and I used to clamber about its crumpled battlements all the time. I was surrounded by history. It made me an addict for life." Christopher's new novel, The Queen's Vow, which follows young Isabella of Castile in her dramatic rise to power, will be available on June 12, 2012. He is also continuing his Tudor mystery series.

Finally, I simply had to this burning question: Can anything else possibly be said about Anne Boleyn?

"I'll say yes," replied Sarah Johnson, "because I know we haven't seen the last of Anne in historical fiction! I'm anxious to read Hilary Mantel's take on her downfall, for example. Every author brings a new angle on her life to the table, or at least tries to." And Christopher Gortner added, "Anne Boleyn went for the crown and she got it. And it destroyed her. But she did it anyway. She's tough to beat, in terms of sheer drama and pathos. "

Christopher concluded, "I often say that in the hands of a skilled novelist, these women can shed their marblized images and reclaim their humanity, in all their glory and foibles. Historical fiction about queens shouldn't really be just about queens; it's about us, too, about how we live and make choices and confront challenges. These women represent us – with more lavish clothes!"

Come back for the second part of this article featuring book bloggers and more novelists.

Ah to live like a queen! If not then, to read about them!

Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

February 5, 2012

Ancient Puppy Chow: Dog Food in Classical Greece

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Chasing game (rabbits, deer, bear, boar) for food and sport was extremely popular in classical antiquity, and dog owners took good care of their hunting companions. Ancient hunting manuals by two Greek historians, Xenophon (b. 430 BC) and Arrian (AD 86) preserve lively practical advice on raising hounds.

So, if you lived in Athens at the time of Socrates and owned a Laconian hunting hound like those depicted on Greek vases, what would you feed them? Ordinary pups get barley bread softened with cow's milk or whey. But more valuable puppies eat their bread soaked in sheep or goat milk. You might add a little blood from the animal you expect your puppy to hunt. At dinner with your family, you scoop soft chunks of bread from the center of a loaf to wipe grease from your fingers—and toss them to your dog, supplemented with bones and other table scraps, perhaps even a basin of meat broth. After a sacrifice or banquet, you make a special treat: a lump of ox liver dredged in barley meal and roasted in the coals. Naturally, as a matter of professional courtesy, you share any rabbits, stags, or boars with your faithful hunting partners.

Was such a diet nutritious? The idea that dogs' principle sustenance must be red, raw meat is a popular misconception. In the wild, canines hunt plant- and grain-eating animals. At the kill, they first eat the stomach filled with predigested grass and cereals, and then the organs, before turning to the flesh. They often gnaw the bones, thus assuring a balanced meal with vitamins and minerals. That Greek dogs thrived on their grain and meat diet is confirmed by Aristotle (b. 384 BC), who remarked that a hard-working Laconian hound usually lived to be 10 or 12 years old, and other breeds reached the age of 14 or 15. Today's average 50 pound dog can expect the same lifespan as Xenophon's Laconian hounds.

Should your dog suffer from worms, wheat awns (whiskers) are recommended. But a more aggressive treatment is Artemesia, wormwood, a natural antihelmintic to expel parasitic worms. What if your neighbors complain that your hound keeps them awake at night? You resort to the ancient cure for excessive barking and conceal a live frog in a lump of his food.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World" (2009) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.