Holly Tucker's Blog, page 87

January 5, 2012

Wonders & Marvels wins Cliopatria Best Group Blog Award

I am delighted to announce that Wonders & Marvels has been awarded the Cliopatria 2011 for "Best Group Blog." The Cliopatria Awards are given annually by the History News Network at George Mason University for the best in history blogging.

Here's what the judges had to say:

Best Group Blog:

Wonders and Marvels This blog is impressive for the large number of contributors and the level of research that clearly goes into each post. It manages to be both generally accessible and academically relevant. It features excellent illustrations and is a great looking blog.

As founder and editor of Wonders & Marvels, I have to say that this award is an important landmark in the life of the blog. Wonders & Marvels began about 4 years ago as a classroom experiment at Vanderbilt University. Since then, I would not be able to count the number of smart posts that my students, academic colleagues, fellow writers, and–most recently–our fantastic Monthly Contributors (see right side-bar) have offered up. Each of their posts have brought interest, depth, and extraordinary expertise to the site.

Speaking of expertise, we're also lucky to have Lindsey Fitzharris among our monthly contributors. Lindsey's The Chirugeon's Apprentice took home the "Best Individual Blog" award. From the Cliopatria judges: "The Chirugeon's Apprentice is 'dedicated to the horrors of pre-anaesthetic surgery,' but this creative and impeccably crafted blog accomplishes much more…the blog brings medical history to a broader audience." And how! If you're not reading Lindsey's site (or W&M for that matter), you're missing out!

My sincere thanks go out to the W&M readers and the hundreds of writers who have made it what it is. A big thanks, as well, to Sumy Designs for their help in making W&M a "great looking blog."

Looks like 2012 is shaping up to be a great year!

January 4, 2012

The Philosopher's Stone: Medical Thought about Immortality

By Elizabeth Fix (Vanderbilt University)

From Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone to Spaniard Ponce de Leon's search for the Fountain on Youth in North America, there are many fantastical legends we've heard of regarding the prolongation and rejuvenation of life. However, the concept of living forever was once founded upon actual medical and scientific thought. Theories to extend one's lifespan began rather simply with Luigi Cornaro's Discorsi della vita sobri, which advocated a healthy diet and all behaviors in moderation as a means to live longer.

These theories grew increasingly radical with the onset of the Enlightenment. In the seventeenth century, Rene Descartes became obsessed with the concept of using medicine to prevent aging. He states, "I believe it may be possible to find many very sound precepts for the cure of diseases and for their prevention and also even for the retardation of aging," and he looked forward to reaping the results of his hard work later in life. Unfortunately, if somewhat ironically, his efforts were cut short by his untimely death at the age of 54. In 1795, Condorcet published the most radical idea of all. He believed that society was constantly evolving and that "the day will come when death will be due only to extraordinary accidents." He believed that better living conditions, inheritance of superior genes, and more comprehensive medicine were the keys to living forever.

Although his ideas were radical, he planted the seeds of associating longevity with social improvement. The work of Descartes, Condorcet, and others, stressed increased longevity as one of the pinnacles of contemporary medicine. Of course, the social implications of people living longer and causing overpopulation could not be denied. Thomas Malthus challenged these thinkers' theories, claiming that not only was an immortal utopia impossible to achieve, but it was immoral. He concludes his attack by noting how presumptuous of Condorcet it was to assume he would be the one to live forever, when countless genius minds had succumbed to death before him. Thus, the Enlightenment quashed rumors of immortality which science had originally propagated.

Source: Gruman, Gerald J. "A History of Ideas About the Prolongation of Life." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 56, Pt. 9. 1966.

January 3, 2012

Nicholas of Poland: A Medical Snake In The Grass

A maker of theriac - a miracle cure that included plenty of serpents. Hortus Sanitatis, 1491.

Suffering from kidney stones? Just drink some wine with a little powdered snake, twice daily. If you have no time to waste or the stone's being especially persistent, go ahead and add powdered toad or scorpion — or better still, add both.

If insomnia or weary eyes are troubling you (and who doesn't suffer these maladies from time to time), have a little water with your pill made of dried frog parts, and don't forget to keep up your general health with an appetizer of properly-prepared snake at every meal.

Sound like snake oil instead of medicine? This was real medical advice supplied by a German-born Dominican friar called Nicholas of Poland, who posed a challenge to established medical prescriptions in thirteenth-century Europe. His career, or what we know of it, caused professional skepticism. After all, how was one supposed to respond to a so-called healer who didn't even taste or view his patient's urine before providing them with a tincture of toad?

Much history written about the thirteenth-century medical landscape which highlights, and takes for granted, a conflict between the 'scholasticized' medicine promoted and taught by a university system rapidly monopolizing medical knowledge, and the uneducated practitioners and even the out-and-out charlatans external to this monopoly.

But as historians like William Eamon and Gundolf Keil have pointed out, Nicholas of Poland occupies a particularly interesting space that challenges our ideas of the relationship between these ways of practicing medicine — a point at the centre of an infrequently-imagined Venn diagram — where an iconoclastic approach to medicine and a university education could fruitfully mingle.

The result proved to be as compelling to medieval health-seekers as it is interesting to us. It was Nicholas' philosophy that humble medicines and amulets made from the lowliest creatures of the earth were good for people of all social stations; the scaly creatures of the ground, used in 'miracle cures' like theriac, were in Nicholas' view, simply packed with God-infused preternatural healing powers that did not need to be understood scientifically to be used.

This philosophy that "great miracles abide in the lowliest things" appealed to Christian ethics, and Nicholas' excellent Latin enabled him to not only defend his position against university-educated physicians (who may have been chagrined at the way his backyard cures undercut their costlier prescriptions while they balked at the deeper intellectual implications of his radical empiricism), but to even go on the offensive against orthodoxy with logic and style.

Nicholas devoted an entire work, the Antipocras (Anti-Hippocrates), to criticize and critique the burgeoning medical philosophy of his day. His other known work, the Experimenta, shared the results of his original experiments into the most medicinally potent preparations of serpent powders and oils, and how to administer them.

Nicholas emphasized that one should collect healing knowledge through firsthand experience, not ancient authority or theory; his quasi-mystical prescriptions were not only theologically-inspired, but also practically supported. This firsthand knowledge would be critical in giving him the grounds to challenge his the visceral and cultural aversion his patients (understandably) had to eating toads, scorpions, and snakes in particular.

The very unpleasantness of Nicholas' cures ultimately became a testament to their power. After all, if eating reptiles and amphibians was so revolting, the idea would be tossed onto the rubbish heap if the ideological underpinnings didn't strike a chord, or the medical results didn't appear to make it worthwhile. In this way, word of mouth created converts not only of other Dominicans, but lofty folk such as the duke of Sieradz and the court and subjects of Leszek the Black, and the villagers in Upper Silesia and Cracow where Nicholas put his empiric philosophy of medicine into practice.

Unfortunately, Nicholas' ultimate fate is murky in the historical record, leaving us bereft of sturdy ground on which to build an understanding of the full significance and endurance of his practice. What exists is, for the moment, merely a glimpse of a unique, albeit isolated branch of medieval medical philosophy that's as repellant to the senses as it is intellectually tantalizing.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She currently studies French, and writes (and copy edits) for the McGill Tribune as well as freelance projects. You can find out more at her About.me page.

December 29, 2011

Sensibility and George Cheyne's "English Malady"

By Liz Deangelo (Vanderbilt University)

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the notion of sensibility became a social phenomenon that permeated the art and literate of the time. Sensibility was a term used to describe an acute feeling of emotion or a quickness of perception. Although it became a term to describe social refinement and good breeding, the idea of sensibility originally developed from medical conceptions about delicate or sensitive nerves.

A fine sensibility or fragility of the nervous system could cause malaises of both the mind and the body. During the eighteenth-century in Britain, various disorders of the nervous system were combined through the umbrella term of nervous disease. Nervous disease encompassed a broad range of distempers, including melancholy, hysteria and anxiety. Furthermore, these nervous disorders mostly beset the British elite, according to the Scottish physician George Cheyne.

In his medical treatise The English Malady: or a Treatise on the Spleen and Vapours, George Cheyne boldly claimed that nearly one third of the English upper-class suffered from a type of nervous disorder, which he called the "English Malady." Cheyne avowed that the climate, rich food and luxury of eighteenth-century Britain contributed to the malady plaguing many of the well-to-do. In particular, women suffered from a type of melancholic hysteria due to the weakness of their nerves. Fainting or swooning indicated the frailty of the female nervous system and became a fashionable way for women to behave. Furthermore, it became fashionable to diagnosis women with a nervous disorder. As one physician from the city of Bath, England once exclaimed to a patient, "Madam, you are nervous." The nervous diagnosis brought together the physical, psychological and fashionable aspects of upper class in eighteenth-century Britain and demonstrates the fluid boundary between medicine and society during that time.

Sources:

Cheyne, George. The English Malady. London, M.DCC.XXXIII. [1733]. Eighteenth Century

Collections Online. Gale. Vanderbilt University. 4 Oct. 2011

<http://find.galegroup.com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/ecco/advancedSearch.do>.

Houston, R. A. "Madness and Gender in the Long Eighteenth Century." Social History 27.3

(2002): 309-26. JSTOR. Oxford Journals. Web. 4 Oct. 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable//508347>.

Jackson, Stanley W. Melancholia and Depression: from Hippocratic Times to Modern Times.

New Haven: Yale UP, 1986. Print

Jordanova, L. J. Sexual Visions: Images of Gender in Science and Medicine between the

Eighteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1989. Print

Schmidt, Jeremy. Melancholy and the Care of the Soul: Religion, Moral Philosophy and

Madness in Early Modern England. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2007. Print.

Van Sant, Ann J. Eighteenth Century Sensibility and the Novel: the Senses in Social Context.

Cambridge: Cambridge Univ., 1993. Print

December 28, 2011

Goya's Madhouse

By Nabeela Ahmad (Vanderbilt University)

In 1789, the French National Assembly proposed a radical document, "The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen," which delineated what would later become the basis of the French Constitution. In 1790, the Assembly released several decrees to ensure provisions within the declaration. The following decree provides a startling but insightful glimpse into the state of psychological treatment in Europe during the late eighteenth century:

Within six weeks of the present decree, all persons detained in castles, religious houses, gaols, police houses or prisons of any other description…unless they have also been sentenced or charged or are awaiting trial for a serious crime, have been stripped of their civil rights, or have been locked up on account of madness, are to be set free.2

Despite its intellectual radicalism, the French Revolution considered the mentally ill on the same plane as common criminals.

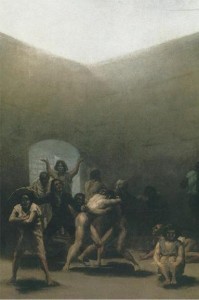

Completed by Spanish artist Francisco Goya in 1794, Yard with Lunatics consummately portrays the situation in the above decree. Following an episode of personal mental and physical breakdown, Goya created a set of works he called caprichos, images displaying Spanish cultural spectacles (e.g. bullfights), which he sent to the Royal Academy of Arts of San Fernando.4 The Royal Academicians referred to this series as "various scenes of national diversions." In a rather dark twist, however, Goya followed by sending the Royal Academy Yard with Lunatics as a conclusion to the caprichos. Goya's letters to Bernardo Iriarte, Vice-protector of the Royal Academy during that time, capture how The Yard with Lunatics is dually representational of Goya's inner torment and the outward treatment of the mad during the late eighteenth century.3

In a letter to Iriarte, Goya indicates, "I have managed to make observations for which there is no opportunity in commissioned works which give no scope for fantasy and invention."3 Yard with Lunatics captures a fantastical, yet grotesquely realistic image of desolation. The painting is dark and muted within the courtyard; the bright sunlight at the top does not enter the courtyard. One man in the center seems to be looking upward in desperation. In a second letter to Iriarte, Goya says the painting " represents a yard with lunatics and two of them fighting completely naked while their warder beats them, and others in sacks; (it is a scene which I saw in Saragossa)."3 Goya's inclusion of Yard with Lunatics within the series of "national diversions," shows, like the French decree, how widely accepted the punitive treatment of the mad and their experience of desolation had become.

Sources:

1. "A Goya Biography." Goya. Museo del Prado, 1961. Web. 17 Nov 2011. .

2. Foucault, Michel. History of Madness. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006. Print.

3. Gassier, Pierre and Juliet Wilson. The Life and Complete Work of Francisco Goya. New York: Reynal & Co., 1971. 109-111.

4. Hilton, Tim. "Something wicked this way comes: Two shows, one of small works by Goya, the other a series of religious paintings by Francisco de Zurbaran, reveal Spain's darkest artists in a new light." Independent 20 Mar 1994. Web. 30

5. "Yard with Lunatics." Graphic. Francisco Goya. 1794. Painting.

December 27, 2011

How to Cure Leprosy According to a Medieval Physician

By Regan Allen (Vanderbilt University)

In its later stages, the body of a medieval leper bore the appalling signs of decay and putrefaction: a misshapen face, numb and deteriorating limbs, festering sores on the skin, rancid breath and a raspy, fading voice. Believed to be highly contagious, this distressing image was the source of vast panic in medieval Europe. The progressing fear of leprosy in part justifies the existence of surprisingly extreme proposed treatments and cures during that time.

Medieval physicians explained leprosy's unsightly symptoms by humoralism, a well-established medical model that divided bodily composition into four fluids, or humors: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Many asserted that an excess of black bile contaminating the blood resulted in the leprous condition. This conjecture resulted in a variety of treatments that aimed to purify the blood and the body as a way to realign the humors.

For example, an alchemist would give a leprous individual a concoction containing gold, a metal that symbolized richness and purity. Lepers willingly drank the solution expecting that the gold would cleanse and restore humoral equality, correcting the infirmity.

Lepers were also submitted to the evacuation of excess humoral fluid through regular bloodletting. Typically, a surgeon would cut a vein near the location of the accumulated corrupt blood. A regulated amount of fluid collected in a pan as it seeped out of a blood vessel, ideally eradicating large quantities of concentrated impurities.

The medieval practice of spilling pure blood through sacrifice constitutes another, more fantastical proposed treatment. Soaking in a bath medicated with the blood of an infant or a virgin was considered a possible cure. A leper who sat in this blood bath expected to undergo what would now be considered like a transfusion: the corrupt blood moves out of the body while the untainted blood moves in to replace it.

In today's Western culture, leprosy exists more commonly as a literary metaphor than as an actual threat to general welfare. However, the same cannot be said for the Medieval Ages, in which leprosy's extensive presence cultivated the development of treatments as extreme as the society's overwhelming fear of the disease.

Brenner, Elma. "Recent Perspectives on Leprosy in Medieval Western Europe1." History Compass 8.5 (2010): 388-406. Print.

Brody, Saul Nathaniel. The Disease of the Soul; Leprosy in Medieval Literature. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1974. Print.

Demaitre, Luke E. Leprosy in Premodern Medicine: a Malady of the Whole Body. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2007. Print.

Zimmerman, Susan. "Leprosy in the Medieval Imaginary." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 38.3 (2008): 559-87. Print.

December 23, 2011

Syphilis as the Disease of St. Job

By Erica Graff (Vanderbilt University)

Today, syphilis is understood to be a sexually transmitted disease that is spread through direct contact with syphilis sores. But this was not always the case.

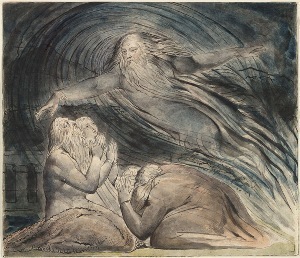

A small group of early modern Europeans referred to syphilis as the disease of St. Job. These pious people generally understood the disease to be a direct message from God. Ironically, however, this idea sheds a comparatively positive light on the often-shunned French Disease.

In its nature and symptoms, syphilis was extremely similar to Job's disease as described in the Old Testament. It was believed that syphilis only affected certain people, as opposed to spreading like a plague. Likewise, God mysteriously sent an unknown disease to Job, and nobody else was affected. Both syphilis and Job's disease were of unknown causes and their symptoms were long lasting and almost unbearable. Furthermore, these symptoms took so many forms that it was nearly impossible to find a cure for the entire disease.

Because not much was known about syphilis, it was most easily explained by creating a parallel with the disease of St. Job. Although some viewed Job's disease as a divine punishment, others believed that it was in fact a test of a layman's faith in the Lord. Many versions of the Book of Job conclude with God rewarding Job's unwavering faith and innocent suffering. Syphilis, then, could be viewed in this same manner because there was no other feasible explanation. If those affected by syphilis remained faithful and unquestioning, then God would bring them a divine cure just as he had brought them the disease.

Thus, some members of the religious community viewed syphilitics more sympathetically. Doctors, who were viewed as God's medical messengers, were more inclined to help treat symptoms. Instead of scolding syphilitics, people tried to morally guide them and assist them in healing and restructuring their lives.

Essentially, syphilis was widely understood to be a horrible disease that appeared as a punishment for immoral behavior in early modern Europe. There was however a small group of people who believed the disease to come from that of St. Job. In this case, syphilitics were a representation of unwavering faith and this presented a more positive image of the disease.

Source:

Arrizablaga, Jon et al. The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. Print.

A Versailles Christmas

Marie Antoinette at Versailles, ornament available at zazzle.com

A few years ago I had the pleasure of visiting the Bibliotheca Bodmeriana in Geneva (a must-do for historical bibliophiles), where the eyes feast on marvels such as a full codex of the gospel of John and a Gutenberg Bible. Among the rare court documents that Martin Bodmer collected over his lifetime sits Elizabeth I's Christmas gift list for her courtiers; names and gifts descend in order of rank. Looking at it, you have a glimpse into Elizabethan holiday ritual. It occurred to me as a French seventeenth-centuryist that I knew little about Noël at Versailles. I turned to the fountainhead of anecdote about the Sun King's reign: the Duc de Saint-Simon.

Louis XIV's outspoken courtier talks about the holiday several times in his 15-volume memoires of the court. Two mentions are incidental and occur because another important event he is describing happens to take place around Christmas. A third that briefly details holiday ritual (Chapter LXXI) is tucked into a description of the religious skepticism of Louis XIV's brother, Monsieur, Le Duc d'Orléans. Saint-Simon sets his story of the prince's ungodliness at midnight mass in Versailles' chapel—three midnight masses to be exact—to which Monsieur accompanied the king. The memoires describe the beauty of the atmosphere as charmed, even for Versailles: music that surpassed the opera, magnificent decoration, and extraordinary lighting. Palace celebration, trimming and all, revolved around the mass.

In the midst of this "brilliant scene," Monsieur sat reading what looked like a prayer book. A lady-in-waiting was moved by the vision of the Duc immersing himself in the spirit of the night and remarked on it. As Saint-Simon recollects it, the Duc responded, "You are very silly, Madame Imbert. Do you know what I was reading? It was 'Rabelais,' that I brought with me for fear of being bored." So much for holy music and fabulous decoration. On Saint-Simon's read, no manner of divine celebration could stop Monsieur from "playing the impious, and the wag," not even Christmas at Versailles.

Christine A. Jones teaches French 17th/18th-century literature and culture at the University of Utah. She writes on fairy tales, porcelain, dance and wine.

December 22, 2011

The Compleat Midwifes Practice

By Kate Stidham (Vanderbilt University)

The Compleat Midwifes Practice is an intriguing midwifery text printed in England during the seventeenth century. The first edition was released in 1656 and the fifth and final edition was released in 1698. The first edition included a preface, descriptions of male and female anatomy, birth procedures and practices, how to care for the mother and child, a series of anecdotes about actual births, and, finally, a letter written from Louis Bourgeois, midwife to the Queen of France, to her daughter describing proper midwife behavior.

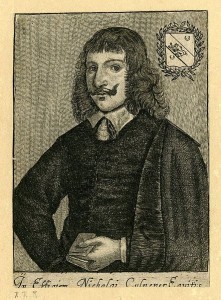

The second edition changed names to The Compleat Midwife's Practice Enlarged and added a section pulling from the works of Nicholas Culpeper, a famous apothecary of the day, describing how to conceive wise, male children.

The third edition added a section from the papers and notes of Sir Theodore Mayern, physician to several kings of France and Charles I of England. This section expands upon the original bulk of the text, adding new recipes to bring about labor and treat various symptoms or discomforts of delivery. The fourth and fifth editions do not add additional content.

The text was produced during a time of change in midwifery. There were a rising number of men becoming interested in childbirth. Surgeons had traditionally been called for difficult deliveries only, but more and more people were relying on them to deliver their children without the help of midwifes.

Because the text has content attributed to female midwifes, male apothecaries, and male physicians and because of the changing times, the question of authorship becomes an interesting one. If women wrote this, they would be endorsing men that are encroaching on their field. If men wrote this, they would be praising the expertise of Louise Bourgeois, acknowledging that women are extremely capable of doing a good job. Unfortunately, there is no explicit naming of the authors or editors of these texts. The first edition was by T.C., I.D., M.S., and T.B., calling themselves practitioners. Doreen Evenden claims that the text was written by female midwives of the day, but with only a series of initials to work with, there is no way of knowing for sure who wrote it.

Bibliography:

Evenden, Doreen. The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London. N.p.: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.

Cody, Lisa Forman. Birthing the Nation: Sex, Science and the Conception of Eighteenth-Century

Britons. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Pechey, John. The compleat midwife's practice enlarged in the most weighty and high concernments of the birth of man containing a perfect directory or rules for midwives

and nurses : as also a guide for women in their conception, bearing and nursing of

children from the experience of our English authors, viz., Sir Theodore Mayern, Dr.

Chamberlain, Mr. Nich. Culpeper ... : with instructions of the Queen of France's

midwife to her daughter ... 5th ed. London, 1698. Early English Books Online. Web.

December 21, 2011

Emotional truth

By Tracy Barrett, W & M Contributor

One factor that draws many people to historical fiction—and Civil War reenactments, the Society for Medieval Anachronism, Renaissance Faires, etc.—is curiosity about how it felt to live at a different time. I share this curiosity; I love to be so immersed in a former time that I'm startled to look up from a book's pages and find myself in the twenty-first century. I first experienced this when reading Lucile Morrison's The Lost Queen of Egypt, and then with Sigrid Undset's Kristin Lavransdatter and Robert Graves' I, Claudius.

Part of my fascination is the evocation of the time—the houses the characters lived in, the food they ate, the clothes they wore, the games they played. But what really draws me in is the feeling that I'm sharing the characters' emotions.

Avoiding anachronism in emotion is one of an author's most difficult feats. How, we wonder, could parents of the past have survived the death of one-third of their children? How could a teenager have accepted without question that she was to marry a man many years her senior, who had been chosen for her by someone else? If the character is horrified, we're not being true to the time. But if we present a child's death or an arranged marriage to an unpleasant old man matter-of-factly, we risk jarring the reader at our character's perceived callousness.

I try to come up with a situation analogous to one today and have my characters react appropriately for that. For example, until modern medicine improved infant mortality rates, parents might react to the death of a child the way most Western people would react to the death of a pet: you'd be sad, you'd probably cry, you'd tell your friends, you'd never forget that pet, you might keep its collar in a special place—but you would move on, in a way that the parent of a dead child could rarely manage to do today.

I think of an arranged marriage as being similar to having parents choose a teenager's high school. The teen might have some say, and if she really, really hated the idea of a particular school and another one was available, the parents might yield to her wishes. But they might not, and that wouldn't be child abuse.

Here's how I handled my main character's reaction in my work in progress to hearing that an acquaintance had lost her husband and children to an illness several years earlier. She thinks: "Not unusual, but sad nonetheless. No wonder the woman had an air of bitterness about her." I hope that reminds my reader that this kind of loss was common, while preserving my narrator's humanity.