Holly Tucker's Blog, page 89

December 12, 2011

Poisoning in the Hungry Forties

By Kaitlyn Berry (Vanderbilt University)

My tender, pretty, smiling babes,

With poison I did slay.

And after that I did cruel take

My husband's life away

This was the chant coming from the crowd of 10,000 that gathered to witness the execution of Sarah Chesham. Chesham, who had a reputation in Essex for her arsenic laced mince pies, was convicted of the homicidal poisoning of her husband in 1849. A few years earlier Chesham had been acquitted for the murder of two of her sons because the arsenic found in their remains could not be traced directly to her. However, it was widely believed that in addition to killing her husband to collect life insurance, Sarah Chesham had murdered her two sons in order to collect burial club money.

In 1849, Rebecca Smith, a middle aged woman with poor health and no money, was convicted and hanged for the murder of her infant son. After the conviction, the bodies of her other nine deceased children were exhumed and traces of arsenic were detected in several of their bodies. Smith later confessed "that she had poisoned her babies, fearing that they might 'come to want'" (Watson 88). Evidently, Smith felt that killing her children was kinder than letting them die slowly of starvation- a common fate of many poverty-stricken children during the decade known as the Hungry Forties.

These two stories are prime examples of the over one hundred criminal poisoning cases reported during the 1840s. The hopeless economic conditions in England and high unemployment rates in the early forties led to an alarming increase in the number of child poisoning and infanticide cases. Poison, especially arsenic, was incredibly cheap and easy to find because of the lack of drug regulations. It offered women like Rebecca Smith and Sarah Chesham an easy solution to their financial woes that could potentially go undetected.

Sources:

Knelman, Judith. Twisting in the Wind: the Murderess and the English Press. Toronto: Univ. of

Toronto, 1998. Print.

Watson, Katherine. Poisoned Lives: English Poisoners and Their Victims. London: Hambledon

and London, 2004. Print.

December 11, 2011

A Bout of Dickensian Anxiety

By Beth Dunn

At first glance, the tale of Charles Dickens' rise to fame and fortune would seem to be one of unhalting advances towards the pinnacle of success that he had achieved by the end of his life. But even the mighty Boz suffered from serious doubts about his skills as a novelist, and his ability to support himself purely by the labor of his pen.

And what do writers do when we think the well has run dry?

We panic.

Charles Dickens had already seen early success — and lots of it — as the author of The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, A Christmas Carol, and Barnaby Rudge, along with assorted other bits and pieces.

Bleak House, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, Little Dorrit, and Our Mutual Friend still lay ahead of him, though of course he couldn't know that.

All he knew was that he had a large and constantly growing family to support, and he was suffering increasingly frustrating bouts of writers block. In the midst of writing Dombey and Son (never heard of it? there's a reason for that), Dickens was so uncertain of his future prospects as a novelist that he took on a job he almost certainly knew he would hate from the start — editor in chief of The Daily News.

Oh, sure, he had been an editor and contributor to various journals from time to time. And he had started his writing career as a sort of beat reporter in Parliament, winning the job largely on the merits of his impressive skills at taking notes by shorthand. And he had always been a crusader against what he recognized as the vast social injustices of the day, which the Daily News promised to rail against until Something Was Done.

On paper, it seemed like the perfect fit. The fledgling newspaper's financial backers wanted a prominent editor who would drive up sales and help their new project compete against the very popular — and very right-wing — Morning Chronicle. And Dickens, who was suffering a serious bout of nerves, wanted a steady paycheck.

You know, in case this whole writing thing didn't pan out.

Within a matter of days, he knew he had made a dreadful mistake.

Eventually, he convinced his best friend (John Foster, who did have a background in journalism) to take over as editor. Dickens had almost from the start hated the daily grind of the paper, hated the pressure, hated being pulled in so many different directions by so many competing interests, hated the corruption of the press in general, of which he was now a part.

So he quit, after only a few weeks.

But the experience was not without its upsides.

First, Dickens had realized that his occasional bouts of writers block were largely due to his absence from the city streets of London. He'd been traveling abroad with his family in recent months, and the quiet countryside was doing nothing for his concentration. When he was free to prowl London's dark and sooty streets at night, he was in his element again at last, and he was back to his old prolific self.

Second, he had finally found decent occupation for his father, a bit of an unrepentant sponge and perennial debtor on whom Dickens would later base his Mr. Micawber. John Dickens had been installed as head of the newsroom at the Daily News, and had taken to it, quite to everyone's surprise, extraordinarily well. He showed up, he managed people, he got the job done. It was really quite remarkable, and even his son acknowledged that he'd finally found his niche.

And finally, perhaps most importantly, Charles Dickens had learned the lesson that so many writers have to learn the hard way.

We're just not really fit for much else, when it comes right down to it.

So we had better just get down to it.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, and makes a habit of reading far too much into the life stories of her 19th century literary heroes.

The Castrato and his Wife

By Helen Berry

Just one of the eighteenth-century equivalents of Warhol's 'fifteen minutes of fame' was if a Georgian man or woman had the opportunity to make a deposition in a notorious court case. Like the stage, the witness stand presented the deponent with a captive audience, and an assemblage of journalists waiting to give their critical verdict in the gossip columns.

Just one of the eighteenth-century equivalents of Warhol's 'fifteen minutes of fame' was if a Georgian man or woman had the opportunity to make a deposition in a notorious court case. Like the stage, the witness stand presented the deponent with a captive audience, and an assemblage of journalists waiting to give their critical verdict in the gossip columns.

One such deponent on 6 November 1775 was Charles Baroe, a Dublin grocer and former room-mate of the Italian opera superstar Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci. Baroe had been called to give evidence in the London Consistory Court (the church court under the authority of the Bishop of London that had jurisdiction in English law over marital disputes).

The case was a libel issued by a young Irish girl, Dorothea Maunsell, for the annulment of her first marriage to Tenducci, although she was by then already married to another man, William Long Kingsman. The success of her libel rested upon the need to prove whether Tenducci was by matter of fact as well as by 'public reputation' a castrato.

Understandably the singer did not submit himself to the humiliation of a physical examination. Proving that Tenducci would have been unable to consummate his marriage to Dorothea was, however, required in law if the marriage was to be annulled. As Tenducci's bedfellow, Baroe had seen the singer in a state of undress. He reported that some years earlier, back in 1765, he had asked Tenducci questions about his castration.

Obligingly, the singer 'thereupon unbuttoned his breeches and shewed…the cicatrice or scar of the said operation, which [I]…clearly viewed, a little above the scrotum or testical bag'. Warming to his subject, Charles Baroe added additional Baroque details for the benefit of the court. In May, 1767, he recalled that he and Tenducci were again lodging together at a house in Dirty Lane, Dublin. Baroe told the court how, 'upon…Tenducci's changing some thing, from one pair of breeches to another', he had observed his friend taking 'a red velvet purse out of one pair of his breeches, to put into another'.

Baroe asked Tenducci what he had got in the bag, thinking it was a relic, to which Tenducci replied 'No; I have got my testicles preserved in this purse, and have had them there since my castration'. Apparently, so the rumour went, the Catholic church deemed it lawful for an emasculated man to take communion, provided he had about his person the severed remnants of his manhood.

Baroe's narrative, and selected highlights from the marriage annulment case involving Tenducci, eventually found their way into the seven-volume edition of T

rials for Adultery: or, the History of Divorces, in which readers could get their fill of 'Adultery, Fornication, Cruelty, Impotence, etc., from the Year 1760, to the Present Time'. The public appetite for such stories appears undiminished over the centuries. But Baroe's 'moment of fame', and the consequences of this court case, reveal much about how Western societies became enmeshed in moral dilemmas surrounding sex and marriage, the modification of the human body for profit, and the ultimate price of fame.

Helen Berry is Reader in Early Modern History at Newcastle University. She is the author of numerous articles on the history of eighteenth-century Britain, and is the co-editor (with Elizabeth Foyster) of The Family in Early Modern England (2007). This is her second book.

December 10, 2011

Al-Kahina: The Berber Boudica

By Eamonn Gearon

Far from being natives of North Africa, Arab armies only entered Egypt in 639. Just 71 years later they crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to begin their invasion of Europe. These remarkable conquests were greater and swifter than any achieved by Greece or Rome. Even so, it was not a story of unbroken victories.

Some uprisings persisted for decades, prompting one Arab governor to declare, "The conquest of Ifriqiya is impossible; scarcely has one Berber tribe been exterminated than another takes its place." The Roman term of opprobrium for any non-Roman – barbarian – became a proper name, creating a Berber identity uniting a people. Unfortunately for the Berbers, this common identity did not equal united resistance.

The most serious Berber resistance was the campaign led by the Berber tribal elder al-Kahina, or "the prophetess." Variously claimed as a Jewess and a Christian by co-religionists, and described as a witch or a sorceress by her detractors, al-Kahina's bravery and desire to remain free of foreign domination inspired others to mount numerous, ultimately doomed, revolts.

Described as a beauty with the gift of prophecy, she put this last skill to good use, sending her sons to her Arab enemies. The Arabs, recognising the skills inherent in the boys' mother, raised them to become successful commanders of Arab armies. In this way, the Berbers were able to claim some glory from a story that is otherwise characterised by defeat and subjugation.

Al-Kahina herself died fighting the Arabs in around 702. Since then, al-Kahina has inspired Berber nationalists, Maghrebi feminists and, in the 19th and 20th centuries, French colonialists! Even today, while virtually unknown in the West, al-Kahina's name is legendary across North Africa, but perhaps she foresaw that too.

Eamonn Gearon is an analyst and historian who has lived and worked across the Greater Middle East for nearly two decades. He is the author of The Sahara: A Cultural History. More information about the book and an author interview can be found at www.eamonngearon.com

About the image: "The Berber Woman" was painted in 1870 by the French Orientalist artist Émile Vernet-Lecomte (1821-1900).

December 9, 2011

The Wonders and Marvels of Teaching

By Holly Tucker (W&M Editor)

Leeches & Lancets: Researching in the Eskind Biomedical Library's Historical Collections

I've talked some, but not much, about the teaching I do as a professor at Vanderbilt University. I could probably do this more often–especially since Wonders & Marvels owes its existence to my work as a teacher.

For those of you who have been regular readers since the beginning, you know that the blog was originally created as part of a teaching experiment in my Early History of Medicine course in Fall 2008.

Students worked on a semester-long research project of their choosing. In addition to writing a traditional research paper, I required the students to present their research to the class–and to write a 250-300 word blog post. What I liked (and still do) about this approach is that my students have to give deep thought to questions of audience and context when presenting their ideas. A research paper is very different than a class presentation. And both are very different than a blog post. Some of those posts are here.

When I taught the class last year, there were too many students in the History of Medicine class to do individual projects. But this semester, it was been something of teaching nirvana. "Leeches & Lancets: Early Medicine, History and Culture" was a small class (14 students), which allowed me to teach the course as both a traditional class and a series of 14 independent studies. This sounds more enormous than it really was. Much of this was because I was teaching the History of Medicine class for the Honors Program at Vanderbilt, which meant that I had a class full of the university's best and brightest. And at a top-ranked university like Vanderbilt, that's saying a lot!

All of this is to say that you're in for a treat over the weeks to come as we post the work of my students, along with our regular content. All posts will be tagged Medicine, Health and Society (Vanderbilt).

I've asked the students to be on call when their post goes live, so they can take questions and join in the discussion. So be sure to chime in!

Agostino Steuco; Renaissance Librarian and Archaeological Explorer

By Katherine Rinne

Built by Agrippa in 19BC, the ancient Aqua Virgo's restoration in 1570 under Pope Pius V heralded Rome's rebirth as "caput mundi," the center of the world. For the first time in nearly six hundred years, an enormous quantity of fresh water flowed into Rome for public and private uses. Earlier restoration efforts were largely ineffectual because the various popes and their engineers couldn't confirm that the Salone Springs, only sixteen kilometers away, were the source. Without that knowledge, failure was ensured.

It was Vatican Librarian Agostino Steuco (1497-1548) who set in motion the successful restoration.[i] He had read De Aqueductibus, a recently rediscovered inventory from 97/98AD of Rome's aqueducts by Sextus Julius Frontinus, Rome's Water Commissioner under Nerva. Using this text, Steuco set out in 1545 to read and interpret the landscape through first hand observation. His goal was to confirm Frontinus's claim that the Salone Springs supplied the Virgo.

Perhaps not as dashing as the legendary Indiana Jones, Steuco must still have cut an interesting figure as he scoured the Roman Campagna tracing the hidden underground aqueduct. He did this by finding and following the original construction airshafts that occurred all along the route. Based on his research, he proposed to Paul III in 1547 that the aqueduct could (and should) be restored in order to facilitate the physical rebirth of Rome, its immediate territory, and the Tiber River. Unfortunately Steuco died in 1548 while participating in the Council of Trent (1545-63), and his proposal wasn't realized during Paul's pontificate. But as he predicted, once the Virgo was restored in 1570 and fresh water flowed, Rome's physical rebirth began.

Katherine Rinne is adjunct professor of architecture at California College of the Arts. Her book The Waters of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the Baroque City (Yale University Press: 2011) won the 2011 John Brinkerhoff Jackson Award for Landscape History from the Foundation for Landscape Studies.

[i] Consult Ronald Delph's work for detailed information about Steuco's career and writings.

December 5, 2011

Before Pepper Spray: The First Crowd-Control Weapons

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Have you ever been pepper-sprayed or tear-gassed? You can create the experience on a small scale by frying fiery-hot jalapeños in oil and then fleeing your smoke-filled kitchen. Oleoresin capsicum inflames eyes, nose, and throat, causing searing pain, restricted airways, and temporary blindness. Tear gas, a volatile solvent invented in the 1920s, has the same incapacitating effects. These two "non-lethal" chemical agents wielded for crowd control are both prohibited in warfare by the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention.

As our stovetop experiment demonstrates, the ability to create a choking cloud of smoke is available to anyone with access to chilis scoring high on the Scoville Heat Index (units measuring Capsicum fire power). Imported from the New World to Asia by the Spanish, hot peppers became indispensable to local cuisines. But peppers could also be weaponized, as the Conquistadors learned. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Caribbeans and Brazilians set fire to hot pepper seeds and let the wind envelop their enemies in clouds of pungent smoke.

Asphyxiating chemical fumes were devised in antiquity, anticipating pepper spray and tear gas by 2,500 years. The Spartans deployed deadly sulfur dioxide gas in 429 BC. In 80 BC, the Roman commander Sertorius defeated rebels holed up in impregnable limestone caverns with an ancient version of tear gas. Noticing that his horse kicked up clouds of caustic lime dust, Sertorius piled up heaps of the white powder in front of the caves. As the prevailing north wind gathered force, the Romans stirred the mounds, raising great clouds that blew directly into the caves. Like tear gas, limestone or gypsum dust becomes extremely corrosive on contact with moist mucus membranes. The rebels surrendered.

A peasant revolt in China was suppressed in AD 178 with the same chemical agent, now delivered by new technology. The emperors' forces manned "lime chariots" equipped with bellows to blast caustic lime powder "according to the wind" into the crowds of protestors.

All three ancient examples depended on friendly winds to avoid blowback, a perpetual problem for those who resort to biochemical weapons. Before the invention of gas masks, kerchiefs soaked in vinegar neutralized noxious fumes, an ancient technique still used by experienced demonstrators facing tear gas and pepper spray today.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World" (2009) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

Monday Check-In

By Holly Tucker (W&M Editor)

So, how'd everyone do on their goals this week? My goal for the week was to work through some of the structural issues that I was having with this next book proposal. I'm happy to report that the issues are resolved–and I'm feeling very good about how things are looking. What I'm less happy to report is that I didn't get as much writing as I had planned in this week because of a fatal miscalculation…I forgot that I was leaving for a conference on Wednesday in Ann Arbor. I also forgot that I had two presentations to prep: one for the conference, and one here at the Vanderbilt Medical School.

So, how'd everyone do on their goals this week? My goal for the week was to work through some of the structural issues that I was having with this next book proposal. I'm happy to report that the issues are resolved–and I'm feeling very good about how things are looking. What I'm less happy to report is that I didn't get as much writing as I had planned in this week because of a fatal miscalculation…I forgot that I was leaving for a conference on Wednesday in Ann Arbor. I also forgot that I had two presentations to prep: one for the conference, and one here at the Vanderbilt Medical School.

How it's possible to forget these things, I just don't know. Especially since I am a calendar and organizational fiend. But I'll give myself a break since it's the craziest time of the semester. It's probably an accomplishment enough to still be standing right now.

Both of the talks seemed to go well. But I'm very, very eager to get back to work on the book. Not sure that I'll hit that crazy deadline of December 7 that I gave myself…but I do know that I don't want this to linger much longer. I was reminded last night as I sat down for a writing session that you've just got to stay with it every day. I didn't think that I had even 15 minutes of energy in me, but as soon as I got the courage to open Scrivener and start writing the words and ideas just flowed. As every writer will tell you, there is no secret to writing. Just do it. Au travail!

How about everyone else? Did you meet YOUR goals?

Manly Menstruation?

In 1780, physician M. Carrere wrote a letter to the French Royal Society of Medicine describing the unusual case of a twenty-five year old miller, Jacques Sola, who bled monthly from his right little finger. Sola became ill with dysentery and peripneumonia in 1764. The cause? Sola's blood flow had been blocked when he stayed too long in the shadow of a windmill. Carrere cured Sola by bleeding him to re-start his 'evacuation'.

Credit: Wellcome Library Images

Two years later Carrere treated Sola for a bloody cough, again caused by the suppression of Sola's ordinary bleeding. Carrere had since moved away, but now wondered if Sola still had regular flows, or if there was 'a fixed time for their cessation' as in women.

Menstruation wasn't understood as specifically connected to reproduction until the nineteenth century. It was one of many indications of female fertility, but all were tied to a woman's overall health. In the Middle Ages, menstruation was seen as poisonous, but eighteenth-century physicians saw it as nature's way of purging women's surplus blood (plethora) that developed throughout the month. When normal menstruation stopped, whether by pregnancy, fright or emotional imbalance, the blood might force atypical routes out of the body. Unrelieved plethora clogged up the body, causing disease.

Since men sweat, they didn't ordinarily develop plethora, although men who were sedentary or ate too much might – like scholars and clergymen. Some plethoric men bled periodically and regularly: by the nose (adolescence), lungs (young men), haemorrhoids (middle-age) and urine (old age). Men and women whose bodies didn't self-regulate needed surgical bleeding to prevent or cure illness.

Physicians and surgeons in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe widely discussed similar cases of 'menstruating men'. The sexed bodies that we see today as being self-evident were ambiguously understood in the past when knowledge was observational: why wouldn't men and women have similar flows?

But throughout the eighteenth century such tales were increasingly rare as medical men began to see male and female bodies as distinct rather than parallel.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

December 2, 2011

Drinking Blood and Eating Flesh: Corpse Medicine in Early Modern England

By Lindsey Fitzharris (W&M Contributor)

In order to restore youth to an aging body, the fifteenth-century practitioner, Marsilio Ficino, advised:

There is a common and ancient opinion that certain prophetic women who are popularly called 'screech-owls' suck the blood of infants as a means, insofar as they can, of growing young again. Why shouldn't our old people, namely those who have no [other] recourse, likewise suck the blood of a youth? — a youth, I say who is willing, healthy, happy and temperate, whose blood is of the best but perhaps too abundant. They will suck, therefore, like leeches, an ounce or two from a scarcely- opened vein of the left arm; they will immediately take an equal amount of sugar and wine; they will do this when hungry and thirsty and when the moon is waxing. If they have difficulty digesting raw blood, let it first be cooked together with sugar; or let it be mixed with sugar and moderately distilled over hot water and then drunk. [1]

At first glance, cannibalistic medical practices such as this seem far removed from our own culture. However, the utilization of body parts for medicinal purposes still persists today, albeit in different forms. Although blood transfusions or organ transplantation may seem dramatically different than drinking the blood or eating the flesh of another human being, these medical practices do share a common belief in the body as an instrument of healing.

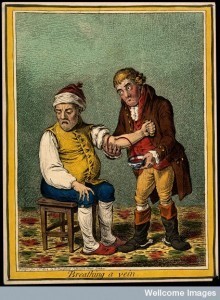

Blood, in particular, featured prominently in the treatment of the sick during the early modern period as it was central to the Galenic model of health which was dependent on a balance of the body's four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile). The image of a patient being bled—his sleeve rolled up, blood pouring from an opened vein into a bowl placed below his elbow—is one which is familiar to us. Less familiar, however, is the image of epileptic patients crowded around the scaffold, cups in hand, waiting to "quaff the red blood as it flows from the still quavering body" of a freshly executed criminal. [2] Thus, blood could be both contaminating in its excess and restorative in its replenishment.

The surgeon's association with blood contributed to the duality of his image during the early modern period. Like blood, he had both the power to heal and the power to harm. [3] Not only would the surgeon come into contact with blood through surgical procedures, but he might also taste a person's blood in order to test its consistency when attempting to diagnosis his patient.

Medicinal cannibalism existed in other forms as well. One of the most common human substances used by apothecaries during the early modern period was mummy, a "medicinal preparation of the remains of an embalmed, dried, or otherwise 'prepared' body that had ideally met with sudden, preferably violent death." [4] Sometimes referred to as "the menstruation of the dead," this remedy was recommended to patients as late as 1747. In The Marrow of Physick (1669), Thomas Brugis wrote:

A Mans Skull that hath been dead but one yeare, bury it in the Ashes behinde the fire, and let it burne untill it be very white, and easie to be broken with your finger; then take off all the uppermost part of the Head to the top of the Crowne, and beat it as small as is possible; then grate a Nutmeg, and put to it, and the blood of a Dog dryed, and powdered; mingle them all together, and give the sick to drinke, first and last, both when he is sick, and also when he is well, the quantity of halfe a Dram at a time in white Wine. [5]

Although the sixteenth-century surgeon, Ambrose Paré, noted that mummy (or mumia as it was sometimes known) was "the very first and last medicine of almost all our practitioners" against bruising, the substance did not come cheap. In 1678, a pound of mummy could cost as much as 5s 4d. [6] Thus, many apothecaries substituted mummy with cheap imitations that typically came from the corpses of beggars, lepers and plague victims.

As popular as "corpse medicine" was during the early modern period, this does not mean it was not without its critics, many of whom described these remedies as cannibalistic and unnatural. By the late eighteenth century, practitioners had stopped prescribing "three drams of [crushed] human skull" for epilepsy, or "two ounces of mummy in a plaster against ruptures." [7] However, the concept of the body as an instrument of healing continued to persist, and indeed, still exists today albeit in a much more dehumanised (mechanised) form.

1. Marsilio Ficino, De Vita II (1489), 11: 196-199. Translated by Sergius Kodera.

2. Mabel Peacock, 'Executed Criminals and Folk Medicine', Folklore 7 (1896), p. 274.

3. P. Kenneth Himmelmann, 'The Medicinal Body: An Analysis of Medicinal Cannibalism in Europe, 1300-1700', Anthropology 22 (1997), pp. 192.

4. Karen Gordon-Grube, 'Anthropophagy in Post-Renaissance Europe: The Tradition of Medicinal Cannibalism', American Anthropologist, 90 (1988), p. 406.

5. Thomas Brugis, The Marrow of Physick (London, 1669), p. 65.

6. Richard Sugg, '"Good Physic but Bad Food": Early Modern Attitudes to Medicinal Cannibalism and its Suppliers', Social History of Medicine, 19:2 (2006), p. 227.

7. J. Quincy (ed.), The Dispensatory of the Royal College of Physicians (London, 1721), pp. 86, 221.

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon's Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.