Holly Tucker's Blog, page 86

February 2, 2012

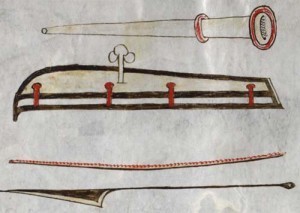

John Arderne, Butt Of No Jokes

By Marri Lynn (W&M Regular Contributor)

You don't want to know where these are going to go. - Sp Coll MS Hunter 251 (U.4.9), 15th century.

When one thinks of the gruesome injuries that could befall a knight in service, one usually thinks of crushed skulls, arrows through the ribs, and unfortunate liaisons between necks and the pointy ends of spears.

John Arderne, a fourteenth-century English surgeon, acquired plenty of experience dealing with these textbook wounds during his service in the Hundred Years War. But he also acquired a particular expertise in treating another knightly occupational hazard which was as uncomfortable for one's pride as it was for one's backside. If the infection down south went south metaphorically, the condition could also prove fatal.

John was the first practitioner specializing in the treatment of fistula in ano, which is, unfortunately, precisely what you'd imagine. John's skills provided many patients from all walks of life, not just knights, with long-term relief. Like modern blue-collar workers stuck behind desks all day while habitually consuming high-fat, low-fiber diets, medieval business folk, scholars, and priests suffered too, and comprised a great portion of John's patient list. Through prolific operations, many of which were pro bono, John earned himself a reputation in addition to a considerable salary, one gained chiefly through the bills he presented the wealthier patients who paid more dearly on John's sliding scale.

In modern parlance, fistula in ano is an ischio-rectal abscess in the anal glands, produced by a handful of factors compounded by long hours in a saddle or a chair. It can lead to perforation of the connective tissue between the anal canal and the body's exterior. When this happens, a passageway is formed which opens up through the perianal skin, suppurating and inviting infection. The social and medical complications caused by a fistula's tunnel-like annexation of the human sewer system are fairly apparent, but despite this, the condition was under-treated in John's time.

Surgeons since at least Albucasis in the eleventh century were equipped with the necessary medical and surgical theory required to treat fistulae, but they were understandably loathe to handle the long line of unfortunates seeking relief. The job was frankly inglorious, messy, and it was usually futile as well. Despite the best professionally-advised caustic ointments and prayers in addition to the use of the blade, fistulae and attendant infections had a tendency to return with a vengeance after being improperly excised. In the context of a battle for professional legitimacy, fourteenth-century English surgeons facing little promise of adequate remuneration from their clientele alongside further risk of losing good standing in the community for appearing incompetent typically chose to avoid these cases whenever possible.

John Arderne's unusual success in treating fistulae became a selling point for his services, and a catapult for his career. By avoiding the use of caustics in his surgical aftercare and by carefully attending and learning from his successive operational experiences, John obtained – and liberally advertised – a high surgical success rate. His skill, and his Latin, enabled him to join a select group of surgeons in England who could call themselves Magister, obtaining within the Guild of Surgeons a professional and social rank which was still below the physician, but adequately above that of the mere barber-surgeon.

In his writings, John leaves the sense of a man who is far from the character one might expect necessary to hedge one's reputation on backsides and their ills. Well-traveled, shrewd, and educated through his experiences more than through dusty halls, John's style was emulated and his name repeated by subsequent writers like the Cambridge physician Johannis Argentin. Hardly a one-trick pony, when he wasn't building on surgical techniques and improving the quality of life for fistulae sufferers, John practiced pharmacy, and has left behind evidence of a considerable knowledge of herbs and their applications. Indeed, following his death in the late fourteenth century, his name carried on more commonly in connection with this less pun-worthy pursuit.

Fortunately for his patients suffering from fistulae and the surgical correction thereof, John also devised and employed an analgesic ointment consisting of no less powerful stuff than hemlock, opium, and henbane.

If one so desires a more detailed account of the surgical treatment of fistula in ano (and who could resist), there is an English translation and reprint of John's Treatises of Fistula In Ano: Haemorrhoids, and Clysters produced by Elibron Classics.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently studying French, while freelancing as a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

January 30, 2012

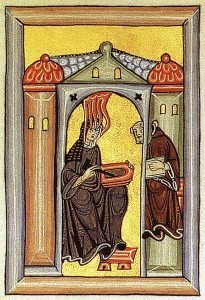

Congratulations, Hildegard!

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (W&M Regular Contributor)

Congratulations to Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)! Pope Benedict XVI has announced that he will recognize her as a Doctor of the Church in October of this year. She will join the ranks of only thirty-three other individuals and she will be only the fourth woman to receive this prestigious recognition. What does this title mean and what is its significance for Hildegard of Bingen?

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, "certain ecclesiastical writers have received this title on account of the great advantage the whole Church has derived from their doctrine." So it wouldn't surprise us to find the likes of St. Augustine, St. Jerome, and St. Bede the Venerable among their ranks. Considering the vast array of ecclesiastical writers and theologians that populate Catholic history, however, the list is surprisingly short and exclusive. And the previous female additions to this canon have come only in the last forty-five years: St. Teresa of Avila (1970), St. Catherine of Siena (1970), and St. Thérèse of Lisieux (1997).

Hildegard of Bingen was a visionary nun of the twelfth century. In addition to recording her visionary experiences, she wrote on a vast array of other topics, including the natural sciences and theology. In her lifetime she corresponded with popes and was sought out by other ecclesiastics for her advice. She also wrote music that has been widely performed and recorded in the modern era. Click here for a sample of from one of these recordings.

The nomination to be a Doctor of the Church must come from the papacy or an ecumenical council (although no council has ever exercised this prerogative). Thus, the decision to nominate may tell us as much about the nominee as it does about the historical context during which that recognition is achieved (an approach that has been effectively applied to the study of canonization proceedings as well).

Benedict XVI appears to have a particular affinity for Hildegard. He has spoken about her in several general audiences dating back to at least 2010. In September of that year he said "She brought a woman's insight to the mysteries of the faith. In her many works she contemplated the mystic marriage between God and humanity accomplished in the Incarnation, as well as the spousal union of Christ and the Church. She also explored the vital relationship between God and creation, and our human calling to give glory to God by a life of holiness and virtue." He has continued to include her in his remarks, indicating most recently his decision to elevate her to the status of Doctor.

Curiously, he will have to canonize her as a saint first, since that is required for the status of Doctor and Hildegard had only previously reached the ranks of the beatified.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

January 23, 2012

Impotence in the Archives: or, a Research Trip Failed

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

A year ago I went to Paris on a week-long research trip. My goal was to look at eighteenth-century impotence trials, part of the Série Z at the Archives Nationales. I planned to compare them with English impotence trials that I had already examined.

French historians and archive workers had been occupying part of the building to protest Sarkozy's proposed (rightwing) museum.

There were the standard research problems, of course. The handwriting was unusually terrible. The boxes were unsorted and contained few, if any, impotence trials, which were challenging to find. But the biggest difficulty was entirely unexpected. Série Z closed for maintenance every second day during that week.* This mystified the counter-staff as much as me. Each time, they were unaware of the closure.

Previously, my research method had been to transcribe notes by hand, then review them afterwards. To the growing number of historians who prefer to take photographs of archival documents, this seems a bit quaint. On this rapidly passing trip with its two fruitless days, I certainly did not have the luxury of time. Instead, I photographed the trial records like mad, writing brief outlines of the cases. Each night I organised the photos and turned them into pdf files, hopeful about the possibilities for my new use of photography. I thought how nice it would be to have images of the documents to hand.

But a year on, I've realised a key problem in this system: much of my work in archives is tied to physical memory. Looking back at my notes over the years, I can remember the way in which documents looked or smelled at the time. More importantly, I can remember where to find specific points in my notes. I recall in detail the stories from the English trial records, but the French ones only fleetingly, even though I have since read through the files a couple times. It has become clear to me that I need another French research trip – this time simply to sit in my office transcribing the files stored on my computer – if my knowledge of the trial records is ever to become potent.

How do you internalise your material when doing research?

*Admittedly, this allowed me to have leisurely lunches and sightsee, so all was not in vain.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800).

January 20, 2012

Captain Kirk to the bridge, please

by Tracy Barrett, W&M contributor

On Star Trek (and by this, children, I mean the real Star Trek—the one captained by James T. Kirk, and with cheesy special effects and constant violation of the Prime Directive), a lot of strange things happen (I'm referring to the strange things that the producers intended to happen, not the accidental ones). The audience has to understand these strange things to make sense of the story. But there are no footnotes in a television show, and a voice-over to explain what's going on would be even more intrusive than mid-60's hairstyles and encounters with space-hippies.

So how to explain?

Enter Captain Kirk. He's got the smarts to run a spaceship but doesn't know a whole lot about the new lives and new civilizations that he encounters. Luckily, he has Mr. Spock, who patiently explains and theorizes about these mysteries to his captain, and hence to the audience. Kirk isn't stupid—he's just a military man whose interests lie elsewhere.

Writers of historical fiction face a similar problem. My Princess Anna of Anna of Byzantium wouldn't think, "Wow, the palace I live in is huge!" But I want my readers to know that it is. Ariadne of Dark of the Moon wouldn't question the human sacrifice that her religion demands every spring. But I want my reader to picture Anna in a huge palace, and Ariadne being a prime player in the sacrifice. So they need someone to explain to: a slave from a distant part of the empire in the first case, Prince Theseus in the second.

Writers of historical fiction face a similar problem. My Princess Anna of Anna of Byzantium wouldn't think, "Wow, the palace I live in is huge!" But I want my readers to know that it is. Ariadne of Dark of the Moon wouldn't question the human sacrifice that her religion demands every spring. But I want my reader to picture Anna in a huge palace, and Ariadne being a prime player in the sacrifice. So they need someone to explain to: a slave from a distant part of the empire in the first case, Prince Theseus in the second.

It's been said that there are only two plots: A stranger comes to town, and Someone takes a journey (some have said that this is really one plot, but from two points of view). I doubt that this is true, but the device is a common one. I wonder if the need for a stranger in town is so the person whose POV informs the story can either explain things to the stranger or be the one who receives an explanation.

January 19, 2012

What do the Rose Bowl and the Ottoman Empire have in common?

By Pamela Toler, W & M Contributor

Marching bands.

Beginning in 1299, the elite corps of the Ottoman armies, the janissaries, used military bands made up of wind and percussion instruments to inspire their troops and terrify their enemies. (Not that different from a half-time show, right?) The music they played was called mehter, a stirring mixture of drums, horn and oboe with a distinctive marching rhythm based on the Turkish phrase "Gracious God is good. God is compassionate." Often four to five hundred musicians accompanied the army. Sometimes the music alone was enough to drive enemy forces from the field.

The European troops encountered mehter music during the seventeenth century wars against the Ottomans on Europe's eastern border. European civilians heard mehter music for the first time when Sultan Suleyman II presented Augustus the Strong of Poland (1670-1733) with a mehter band of his very own. Europe was fascinated by the new sound; by 1770 most European armies had bands featuring Turkish instruments and fanciful variations of Turkish costumes.

Turkish music also played into the taste for turquerie (otherwise known as "Turkish stuff") that swept European society in the eighteenth century. Popular composers, including Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart, wrote "Turkish" symphonies, ballets, and operas using new percussion instruments borrowed from the Ottomans– bass drums, snare drums, cymbals, triangles, and Turkish crescent (also known as the "jingling Johnny"). The fashion reached its artistic height in 1777 with Mozart's Escape from the Seraglio. The fad for turquerie soon ended, but Turkish percussion instruments found a permanent home in the western symphony orchestra.

In 1826, the janissaries mutinied against Sultan Mahmud II. They were slaughtered by troops loyal to the sultan and the mehter bands were dispersed. Today a mehter band is attached to the Istanbul Military Museum. The band performs several times a week in a specially designed auditorium. It's well worth hearing, but take your earplugs. Mehter bands don't have an indoor voice.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

January 13, 2012

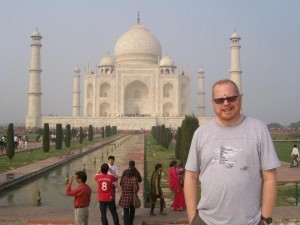

The Taj Majal: From a rare angle

The author partakes in the opportunity to have his personal iconic shot taken in front of the Taj Mahal.

By Todd F. P. Hughes (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

The Taj Mahal has the fame of being one of most iconic demonstrations of love for one's spouse on the face of the planet. Finished in 1638, after almost 20 years of labor, it is the final resting place of Mumtaz Majal, the first and favorite wife of the fifth Mughul Emperor, Shah Jehan.

I think that, for several reasons, the term iconic is very important in any consideration of this edifice. First, as I previously mentioned, it serves as an iconic demonstration of love. Second, it serves as a cultural icon. For much of the world's population, the Taj Mahal is India. Third, we associate cultural icons with the Taj. Lady Di's 1992 visit to Agra is forever ingrained in our conscience, as a result of her iconic photo in front of the Taj Mahal. Finally, the representation of the building, in our collective consciousness, is iconic. When we imagine the Taj Mahal in our mind's eye, we represent it in one form: from a distance, straight-on, and from the front.

I became aware of this phenomenon when I recently went to Agra to see the Taj. Seeing the building, from that frontal iconic view, took my breath away. Surprisingly, what I found even more inspiring was that the building had dimension. Yes, it is much more than what you see in those two dimensional pictures. It actually has depth!

Fortunately, you will not need to travel all the way to Agra to quickly appreciate a 3D vision of the Taj Mahal. Google has provided us with a model of the building, created in SketchUp, which we can download and manipulate. An advanced modeling tool, it allows us to turn the Taj Mahal on an axis, in order to see that yes… it does have four sides.

Todd Hughes is the Director of Instructional Technology at Vanderbilt University's Center for Second Language Studies. He team teaches a course on Digital Humanities with two other W&M contributors. He is also a fanatic for world travel.

January 10, 2012

The Silent World of Leo Lesquereux

By Bob Silliman (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

Leo Lesquereux (1864)

In 1848 Leo Lesquereux left his native Switzerland for America. Initially a teacher and then a watchmaker, he had turned to natural science and had become the foremost expert on peat in Europe. Finding it prudent to take his family to the New World in this age of revolution in the Old, he hoped to transform his knowledge of peat into a new scientific employment in America joining the vital enterprises of his fellow Swiss emigrant, the celebrated Louis Agassiz. Although his connection with Agassiz was a distinct advantage, the fact that he was profoundly deaf was a serious drawback in the work he chose, explorations in fossil botany, and in everything else.

Yet after unstinting labor he became the leading student of coal flora and a pioneer in the establishment of fossil botany in the country. Travel in an unfamiliar land to discover new specimens was full of difficulty, as were his attempts to communicate with "the Yankees." Sometimes he encountered bizarre situations. Once, travelling by steamboat on the Tennessee River, a new passenger came on board. Friendly conversation between the two men posed a challenge. The blindness of the one prevented him from seeing the words the deaf man wrote on his tablet. The other with his poorly spoken English couldn't follow the discourse of the second. But the dilemma was resolved. When Lesquereux posed a question, his companion replied by pointing to a passage from the Bible that provided an appropriate reply. When the steamer reached Gunthersville, Alabama, the common destination of the travelling pair, and they were disembarking they suddenly fell from the dock into the swollen river. Together they scrambled up the muddy bank and in the morning, more or less dried out, they continued their journey together on foot.

Deafness, which Lesquereux regarded as a divine test of character and purpose was nonetheless a heavy cross to bear and not to be wished upon anyone. Yet Lesquereux, believing his career was under divine direction, saw more than one advantage in his disability. In his social isolation he was able to concentrate on his scientific work more completely than he otherwise could have and was able greatly to enlarge the scope of his scientific achievement.

Bob Silliman earned his Ph.D.in the Special Program in the History and Philosophy of Science at Princeton. He is retired from Emory University, where he taught European History and the History of Science. His research and publications have focused on the role of biographical components in the development of the sciences, especially 19th-century physics and geology. Bob is currently working on a biography of Leo Lesquereux.

January 9, 2012

Muffin Man

By Beth Dunn

Was George Handel and a buttered muffin inadvertently responsible for the creation of the British Museum?

Well, probably not.

But honestly? I wouldn't rule it out, either.

So you know the British Museum. First public secular museum, established in 1753 when Sir Hans Sloane passed away and left his absurdly large and varied collection of rare books, antiquities, and just downright oddities to the British Crown.

Sloane was a wildly successful London doctor, one who counted Samuel Pepys and Queen Anne among his patients, and who had amassed a cabinet of curiosities so large that he had to buy the house next door just to give him enough shelf space for it all.

Distinguished visitors would come from all over to peer at his whatnots, to marvel at his whoosits.

Then he passed away and left it all to the nation, who responded with characteristic ingratitude, a great deal of Parliamentary wrangling, and no small amount political corruption that eventually resulted in the creation of the British Museum.

What's odd about this story is that it is hardly possible to research the early days of the British Museum without coming across the following story with what one can't help but notice is alarming frequency:

Sloane's house was visited by numerous people. Among them was the composer Handel, who is said to have outraged his host by placing a buttered muffin on one of his rare books.

For the life of me, I cannot stop thinking about that damn buttered muffin.

What kind of muffin was it? Was it more extravagantly buttered than most? Exactly what sort of baked good was called a muffin back in the 18th century, anyway?

Was Handel some sort of countrified rube, who simply thought that rare books made excellent substitutes for plates and saucers, or was he trying to make some kind of point? What book was it?

Was it this near catastrophe that convinced Sloane that his collection needed the protection of the British Crown, once he himself was no longer around to protect his books from the menace of butter-laden muffins, crumpets, and scones?

Even more intriguingly, is there in some dim and dusty corner of the British Library (where all the books of the British Museum eventually found a home) an old, rare book with one very faded, but barely discernable circular grease stain on it?

These are the sorts of questions that leads one to investigate, late at night and into the early morning hours, the history of the English Muffin, and to discover (to one's great delight) that the muffin was in fact a highly fashionable foodstuff in the 18th century.

Which would explain why it was being served to distinguished visitors to what one has to assume was one of the more exclusive drawing rooms in London at the time.

Muffins were huge. They were a tremendous fad, catching on among the snacking classes with such fervor that scores of muffin factories soon popped up all over London. Jane Austen even mentioned muffins in her novel Persuasion, and not merely as a particularly apt way of describing the hot, buttery Captain Wentworth.

Did Sloane realize the peril his collection might be in, if left open to the slings and arrows of outrageous baked goods?

Or was Handel just a bit of a jerk?

Hard to say.

But in the midst of this deeply appealing line of research, I suddenly remembered another buttered muffin story, this time about one of the American founding families. I got very excited for a few minutes, imagining that the tale of the buttered muffin was some sort of universal flood story, found in one form or another in all known cultures, varying only in the shape and size of the muffin, or in the amount of butter involved.

Alas, it was a more prosaic tale that that. Something about a young lad who was named after Benjamin Franklin, and who took it upon himself to instruct First Lady Dolley Madison in the art of properly buttering your muffin. If you'll excuse the expression.

'Why, you must tear him open, and put butter inside and stick holes in his back! And then pat him and squeeze him and the juice will run out!'

Which seems a very sensible way to eat a buttered muffin, if you ask me.

What's truly excellent about this story is that it is a reminiscence of Thomas Jefferson's great-granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Harrison. And that the story took place at Monticello.

Buttered muffins. Present at the creation of so many great things.

Perhaps now you, like me, wish to know just how Thomas Jefferson ate his muffins.

Very well, I shall tell you.

To a quart of flour put two table spoonsfull of yeast. Mix . . . the flour up with water so thin that the dough will stick to the table. Our cook takes it up and throws it down until it will no longer stick [to the table?] she puts it to rise until morning. In the morning she works the dough over . . . the first thing and makes it into little cakes like biscuit and sets them aside until it is time to back them. You know muffins are backed in a gridle [before?] in the [fire?] hearth of the stove not inside. They bake very quickly. The second plate full is put on the fire when breakfast is sent in and they are ready by the time the first are eaten.

Who's hungry?

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, and gets pretty worked up sometimes about baked goods.

January 8, 2012

Medea's Cauldron of Rejuvenation

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

The Persian sorceress of Greek myth, Medea, understood arcane pharmaka (drugs and poisons) and knew how to concoct unquenchable "living fire" (volatile naphtha from natural petroleum wells of Baku, Azerbaijan). Medea, whose name means "to devise," also knew the secrets of rejuvenation and resurrection. She used magical formulas and quasi-scientific procedures to achieve power over life and death.

According to myth, Medea first demonstrated her uncanny ability to recapture youth when she appeared as an old woman and suddenly transformed herself into a beautiful young princess. Jason, of the Argonauts, became her lover and asked Medea to restore the youthful vigor of his aged father, Aeson. Medea's treatment recalls twentieth-century celebrity rumors about miracle youth cures in secret Swiss labs. In the first example of fabled "whole-body blood replacement," Medea drew out all the blood from the old man's veins and replaced it with the restorative juices of certain plants. Old Aeson's energy and glowing health amazed everyone who saw him.

The daughters of Pelias, hoping to rejuvenate their father, too, begged Medea to reveal her procedure. But Pelias was an old enemy of Medea's. The sorceress set her special bronze cauldron boiling over a fire, reciting incantations and sprinkling powerful pharmaka. Amid great clouds of smoke, Medea dramatically cut the throat of an old ram and placed it in the big kettle. Abracadabra! A frisky young lamb magically appeared in the pot. Pelias's gullible daughters attempted the same technique with their elderly father, with horrible results.

The earliest image of Medea in Greek art is on a vase painting of about 630 BC. As she stirs her "cauldron of rejuvenation," a sheep emerges from the pot; a similar scene appears in many other ancient paintings of Medea. Looking at these archaic images today inevitably brings to mind the world's first genetically engineered sheep, Dolly, who emerged from the first successful cloning experiment in 1997. Medea's mythic method for renewing life—creating a younger version of an older creature—anticipates by more than 3,000 years modern advances in cloning, stem cells, high-volume blood and non-sanguineous transfusions, and other scientific techniques for renewing organs and achieving artificial life.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of "Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World" (2009) and "The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy," a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

January 6, 2012

My thousand historical research books

some of my book shelves

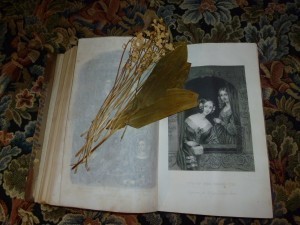

1848 Lady Book with old pressed flowers

I have been accumulating research books or, when they are very rare, consulting them since I first began to write historical novels. In the late 1980s when I began we still had many used book shops in New York City with wood shelves too high to reach but by ladder, shelves often sagging with the weight of books and with that definite smell of wood, dust, old paper, old bindings. Each new book was an enchanted encounter.

I have published five historical novels and have more in draft than I'm willing to admit. Each began with a history book: a rare volume on Elizabethan London printed about 1894 with a red binding which I found I don't recall where, a biography with fragile pages of a 17th century English archbishop which was waiting for me in a very small shop for very little money. A small book with leather covers and gilt-edged pages by Marcus Aurelius discovered in a cold, empty New England book barn where there were tens of thousands of books and the footsteps of one lone browser…me. The original 1665 book on the early microscope by Robert Hooke (Micrographia) in the New York City Arents Collection and one of the thirteen extant copies of Shakespeare's 1609 sonnets perused and almost wept over at Yale. (Was this WS's own copy perhaps?) And the rather astonishing heavy Victorian Godey's Lady Book printed in 1848 and given to me by a friend, between whose pages I found a sheath of very dry flowers and leaves, almost colorless. (Who pressed them there and tiptoed away?)

I bought more books by catalog in the 1990s: newer books but on rare subjects such as a history of English workhouses, the Glastonbury Tor. In my travels I bought books. On my trip home from England I brought twenty-seven books. That was before the planes weighed your luggage or perhaps the weight allowance was higher. (I think I gasped with delight when I found a map of Elizabethan London.)

Then came the fabulous internet and every book I ever dreamed of waiting in some shop in Arkansas or the Cotswolds for me. I ordered How Shakespeare Spent the Day. I ordered an old book on the daily lives of French artists. And now my husband has given me a Kindle and I have found to my extreme delight a number of books on 1860's Florence published in that time and all for free. One has a list of banks and food shops of the period and where you can hire a donkey cart.

And when I finish a historical novel, what happens to the books? Well, I give some away sometimes. I truly recall giving several away which I had used for my Monet novel so do not understand why a huge pile of them still weigh down the top of a file cabinet in the den. My books on the Brownings are scattered all over the house but my English history books are mostly in one whole shelf. Sometimes I wander from room to room touching the book spines. I hear the books murmuring softly, "And when will you write me? There is a story waiting within my pages! What are you doing researching that other book in the next room…I know all about you, you see!"

And I tell them, "Perhaps 2012 will be a good year for your story!" I know they are patient books though they do grumble in their dusty way and that they know in their inky souls that I truly love them and that I will come back.

Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.