Holly Tucker's Blog, page 82

May 18, 2012

Muslim Spain–The Sound Track

By Pamela Toler

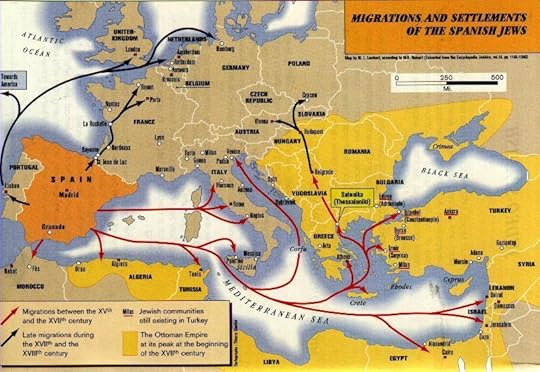

Map courtesy of the Denver Public Library

These days, I’m spending a lot of time in Muslim Spain–a golden age of cross-cultural pollination by any standard. At a time when most of Europe was wallowing in the Dark Ages, Muslim Spain was a center of wealth, learning–and (relative) tolerance. If you wanted libraries, hot baths, or good health care, Spain was the place to be.

I recently discovered the perfect soundtrack for thinking about Muslim Spain: the ladino music of Yasmin Levy.

Ladino is the Sephardic equivalent of Yiddish. (Sephardic comes from the Hebrew word for Spain.) Spoken by the Jews of Muslim Spain, ladino began as a combination of Hebrew and Spanish. When their most Catholic majesties Isabella and Ferdinand expelled the Jews from Spain in 1492, most of them sought protection in the Muslim states of North Africa and the Ottoman Empire. Over time, their language took on elements of Arabic, Greek, Turkish, French, and the Slavic languages of the Balkans.

Ladino music, too, carries the history of the Sephardic community in its sound. It has elements in common with Portuguese fado, Spanish flamenco, and Jewish klezmer music.

Take a moment to listen as Yasmin Levy sings El amor contigo, from her latest album, Sentir (To Feel)

Remember. You heard it here first.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

May 16, 2012

On Vessels Filled and Fires Kindled

Light it up ... by young_einstein via Flickr

“The mind,” Plutarch is said to have said, “is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.” This pithy formulation seems to have been distilled at some point from Plutarch’s lecture, entitled On Listening to Lectures, in which, as the Loeb translation has it, he writes:

For the mind does not require filling like a bottle, but rather, like wood, it only requires kindling to create in it an impulse to think independently and an ardent desire for the truth (De Recta Ratione Audiendi, 18, 47, c).

Plutarch thus emphasizes that education requires active listening, because learning is not merely the passive reception of information. The metaphor of kindling points to learning as an active process, and teaching becomes a matter of nurturing independent thinking and cultivating a desire for truth.

There can be little doubt that the transition from print to digital culture through which we are living has sparked a revolution in literacy that is exerting enormous pressure on traditional practices of pedagogy. As Donald Clark has suggested in his TEDxGlasgow talk, there as been more pedagogic change in the last 10 years than the previous 1000. Strangely enough, however, the pedagogical practices Plutarch advocated almost 2000 years ago seem more germane to a digital culture of pedagogical creativity and collaboration than does the dystopian image below:

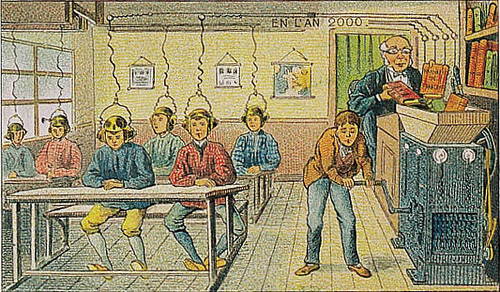

Villemard 1910 - En L'An 2000 - At School via amphalon on Flickr

This postcard, imagined and illustrated by French artist Villemard for a series titled “Utopie” in which he envisioned life in Paris in the year 2000, depicts education as the uploading of information. Here books are ground into a digital pulp and, returning to Plutarch’s simile, the minds of the students are filled like bottles.

Mekanikkforelesning i S3 by NTNU Engineering Science and Technology, on Flickr

Sadly, of course, this is precisely the sort of pedagogical practice one encounters every semester in thousands of classrooms around the world. It is difficult to see how this model of education can inspire the independent thinking and ardent desire for truth of which Plutarch eloquently spoke so many years ago.

But as we adopt new practices of pedagogy adapted to the new affordances for collaborative teaching and learning offered us by digital technologies, we will do well to recall regularly, and repeat frequently, the final words of Plutarch’s lecture on listening to lectures. There he enjoins us …

… to cultivate independent thinking along with our learning, so that we may acquire a habit of mind that is not sophistic or bent on acquiring mere information, but one that is deeply ingrained and philosophic, as we may do if we believe that right listening is the beginning of right living.

References

Plutarch. Plutarch: Moralia, Volume I. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library, 1927.

The Villemard image is used with permission from Tom Wigley (aka amphalon on Flickr). Here is his set of Villemard’s 1910 postcards on Flickr.

May 13, 2012

A Boatload of Knowledge

Thomas Say, noted hottie

Somewhere in the library of Drexel University in Philadelphia a portrait hangs. It depicts a reasonably young, reasonably handsome man of apparently good humor and warmth — Thomas Say, noted America entomologist and conchologist. Of course portraitists can famously commit all manner of falsehoods in the name of pleasing their clients, and it’s entirely possible that Thomas was not half as kind and warm a man as his portrait might imply.

But his portrait, as well as the story of his singular personal and professional life, does make a powerful argument that he was at least an interesting one.

The library director at Drexel, in whose office Thomas hangs, is on record as saying that this portrait is the “most handsome depiction of the most handsome 19th century man” she’s ever seen.

Well. I know a few people who might contest that distinction. But let’s not get bogged down in what can only in the end be a purely subjective debate about who had the handsomest eyes in the 19th century. Fascinating though this debate may be.

While Thomas Say’s latter-day designation as a 19th century hottie may be what catches the eye, the man’s actual career is fascinating enough in its own right. Already a successful and highly respected natural scientist by the age of 25, Say was a founding member of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. He formed lasting friendships with many of the most respected and prolific scientists of the day, each of whom it seems can lay claim to being the “Father of American” this or that. Auspicious company, indeed.

And it was in some of this auspicious company that Say travelled to Indiana in 1826 on the delightfully named “Boatload of Knowledge,” a gang of top scientists headed for the utopian community of New Harmony that was then in its heyday of attracting the best minds of the young republic.

The heyday didn’t last long, as is so often the way with utopian societies. But Thomas met his future wife, Lucy Sistare, on the aforementioned Boatload of Knowledge. Lucy was herself a gifted illustrator of the natural sciences, and would in fact go on to be the first woman elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences. Her own thoughts on her husband’s relative attractiveness have not been recorded, though perhaps they can be reliably inferred.

While New Harmony was dissolved as early as 1829 — only four years after its founding — due to the usual squabbles that tend to accompany experiments in community living, its reputation as a home for intellectual inquiry apparently lived on. Say stayed on in New Harmony until his death in 1834, after a highly productive career detailing the insects, mollusks, and other beasts of North America. His affinity for an austere manner of living evidently never paled, and he stayed on in his rustic New Harmony cabin, presumably attended to loyally by his devoted Lucy, for the rest of his life.

New Harmony continued to attract and nurture men of a strong scientific bent, including David Owen, a son of the settlement’s founder Robert Owen, who went on the become the state geologist for several states. Another Owen son would be the state geologist of Indiana and served as the first president of Purdue University. Yet another son would serve in the House of Representatives, eventually introducing the bill that established the Smithsonian Institution.

The attractiveness of the sons of Robert Owen, and the alleged loveliness of their eyes, has not been recorded for posterity.

A final side note on the illustrious town of New Harmony and its powerful attraction for those of powerful intellect: Eminent 20th century theologian Paul Tillich is buried here, for no apparent reason other than he once spent some time there and felt an affinity with the place. Clearly, there’s something about New Harmony that continues to resonate with the music of the spheres, or at least with those who spend so much of their time listening and humming along.

Tillich was, of course, noted for having very fine eyes indeed.

Not really. I made that up. But he was a pretty good jumper.

Beth Dunn is a novelist, blogger, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady and is unshakably loyal to Robert Cornelius as having the finest eyes of the 19th century.

By the way, the portrait above of Thomas Say is not the one that hangs in the library. That one’s here. I just like this one better, that’s all.

Read more about the Boatload of Knowledge (PDF download of a highly readable scholarly article from the Ohio Journal of Science). It’s a pretty remarkable story.

May 10, 2012

The vulva goes on pilgrimage

In a recent post, W&M contributor Tracy Barrett mentioned in passing the pewter badges worn in the hat during the Middle Ages, and in a moment of recognition I felt compelled to respond with my favourite one, showing a vulva wearing a jaunty pilgrim’s hat. I found out about these tiny objects when I was at an academic conference on the history of the penis (my mother never quite believes the things I get involved in…) held at the wonderful Italian town of Massa Marittima. One of the speakers was Malcolm Jones, who has worked on medieval pilgrimage and talked about these pewter badges as souvenirs. In his book The Secret Middle Ages, Malcolm looks at the various designs of the badges, and suggests that this one is making a joke about the real reason why women go on pilgrimage – it’s to get away from home and have some fun. Rather like going to the Costa del Sol today. Sort of.

The badges are striking because they are so tiny, so fragile, and could so easily have become an aspect of medieval life that was lost to us. In fact, many thousands have been found, with Amsterdam and Rotterdam being associated with particularly large collections, but they are still being studied, catalogued – and understood. They were cheap, mass-produced, items, and they could have been used as presents from someone on his or her return from a pilgrimage, or ways of signalling one’s political allegiance. Some have images from folk tales so they give us an idea of what stories were being told when they were made and sold. They could be placed over the bed, or kept beside it, to fend off disease or enhance fertility. Many have been found near rivers – deposited there in thanksgiving for a safe passage? The erotic ones mostly date from the end of the fourteenth century or the beginning of the fifteenth century; as well as the vulva, they feature the penis having its own fun and games. Scholars have speculated about whether wearing one of these badges is a sign that the wearer is available for a sexual encounter. It’s difficult to know, as there is not much written about them in literary sources. But this is why they are so interesting – they give us another angle on the people of the middle ages.

The badges are striking because they are so tiny, so fragile, and could so easily have become an aspect of medieval life that was lost to us. In fact, many thousands have been found, with Amsterdam and Rotterdam being associated with particularly large collections, but they are still being studied, catalogued – and understood. They were cheap, mass-produced, items, and they could have been used as presents from someone on his or her return from a pilgrimage, or ways of signalling one’s political allegiance. Some have images from folk tales so they give us an idea of what stories were being told when they were made and sold. They could be placed over the bed, or kept beside it, to fend off disease or enhance fertility. Many have been found near rivers – deposited there in thanksgiving for a safe passage? The erotic ones mostly date from the end of the fourteenth century or the beginning of the fifteenth century; as well as the vulva, they feature the penis having its own fun and games. Scholars have speculated about whether wearing one of these badges is a sign that the wearer is available for a sexual encounter. It’s difficult to know, as there is not much written about them in literary sources. But this is why they are so interesting – they give us another angle on the people of the middle ages.

And Massa Marittima was chosen to host this conference because of a fresco found there in 1999. Probably dating to 1265, this shows a ‘penis tree’. I know – not exactly a familiar concept! Women are shown collecting the penises dangling from the tree, and in one case fighting over one. The fresco was associated with a set of fountains, but George Ferzoco has argued that this is not about fertility and the life-giving powers of various fluids – instead, he reckons, the image is part of a political struggle within the town, with one side attacking the other as bringing conflict. Recently there has been a further conflict over the fresco – with its restorers being accused of covering up some of the penises! (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/ar...)

Would you like a replica of one of these badges to wear? Tracy and I would be interested – although so far I have not seen them in any museum shops…

Reading: Malcolm Jones, The Secret Middle Ages: Discovering the Real Medieval World (2002)

George Ferzoco, The Massa Marittima Mural (2004)

May 8, 2012

The Chocolate Baby

Marquise de Sevigne Chocolates

One of the strangest anecdotes to emerge from the already larger-than-life annals of Louis XIV’s reign concerns a perfectly forgettable woman, the Marquise de Coëtlogon, who lives on in infamy because she (apparently) had a chocolate addiction and the famed letter-writer Madame de Sévigné found out about it.

As the epistolary paparazzi of her age, Sévigné caught on paper more extraordinary plots, rumors, oddities, triumphs, and scandals than any other courtier at Versailles. To be in her midst was to risk public exposure—although she wrote her sensational tales in letters to her daughter who lived far from court in the 1670s and 80s, they also circulated regularly to others. If she was nearby when a wedding was announced or a dinner party bombed, it went out with the evening post and could be trotted out for months to come when the perfect occasion presented itself. Such was the fate of the Marquise de Coëtlogon’s darkest day.

Her story began in simple aristocratic fashion: Péronelle-Angélique de la Villeléon, hier of the noble Bois-Feillet Manor in Brittany, grew up to marry René-Hiacinthe, the Marquis de Coëtlogon who served as Governor of Rennes in the ranks of Maréchal de France and descended from a family of 12th-century knights. Their proud houses were joined on July 3, 1664 and Péronelle-Angélique became a Marquise. In 1669, she conceived a child and, for reasons unknown, drank a lot of hot chocolate.

Then a new sensation in Paris, chocolate had arrived from Mesoamerica via Spain. From the early 1670s, chocolate attracted the attention of medical and mercantile communities that saw in it a potential goldmine. It was hailed in medical treatises as a potent drug whose biological effects could not be entirely separated from its foreignness. Presented as a sophisticated cure whose misuse could cause pain or worse, chocolate was tainted by concerns about excess and magical power. No wonder Paris eagerly sought it out. Before its effects on the body could be understood and fully separated from concerns about propriety, the high nobility self-medicated and enjoyed it with excited suspicion.

Madame de Sévigné talks several times about chocolate in her letters of 1671, and vehemently so during her daughter’s pregnancy, when she trots out the legend of Coëtlogon the Chocohaulic as a horrific cautionary tale:

“But what do you have to say about chocolate? Are you not afraid of how it can burn the blood? What if all the effects that appear miraculous mask some sort of diabolical combustion? What do your doctors say? In your fragile state, my dear child, I need your word [that you will not drink it], because I fear that you will suffer these problems. I loved chocolate, as you know. But I think it did burn me; and furthermore, I have heard many terrible stories about it. [...] The Marquise de Coëtlogon drank so much chocolate when she was pregnant last year that she gave birth to a baby who was black as the devil and died.” (25 October 1671, translation mine)

Thus, the legacy of the ill-fated Marquise, about whom we know little else, was to have her greatest personal misfortune showcased in a story about the hazards of chocolate. The absurdity (not to mention latent racism) of the claim notwithstanding, Sévigné records a mentality that found thrill and danger in the exoticism of the foreign drink in the days before it became fashionable in Europe to overindulge in the pleasures of chocolate. In an odd twist of fate, Sévigné, who learned to love her hot cacao, was immortalized on the marquis of a maison de chocolat in 1898. Marquise de Sévigné chocolate shops still thrive in Paris today and her face circulates in silhouette on their signature morsels.

Christine A. Jones is Associate Professor of French and CLCS at the University of Utah and a regular contributor to W&M.

May 6, 2012

Monkeys with Guns

By Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Armed and dangerous! Not a phrase that leaps to mind to describe monkeys, except in science fiction fantasies. Indeed, to promote the movie “Rise of Planet of the Apes” (2011), 20th-Century Fox created a YouTube video that quickly went viral, showing a chimpanzee terrorizing African soldiers with an AK-47. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhxqIITtTtU

As bizarre as the notion of employing monkeys as soldiers seems, the possibility has occurred to military commanders seeking secret weapons and surprise tactics. Monkeys’ intelligence, physical agility, ability to emulate humans, and capability to manipulate simple mechanisms means that they are easily trained to play a role in warfare.

Who were the first monkeys to see action in war? Before the invention of gun powder fire-arms in China (ca 13th century), a 9th century Chinese chronicle (“Yu-yang-tsah-tsu” by Twan Ching-Shih) describes annual battles between soldiers of Po-mi-lan and 300,000 giant rock-throwing apes who came down from the high craggy mountains of the west to ravage crops every spring.

The earliest documented case of gun-toting monkeys appears in a Chinese account of 1610 (“Wu-tsah-tsu” by Sie Chung-Ghi). It describes General Tseh-ki-Kwang’s campaign against Japanese marauders in the 16th century. Capturing a troop of monkeys from Mount Shi-Chu in Fu-Tsing, he and his men trained the simian recruits to shoot fire-arms (or at least aim). When the general sent the monkey militia to the front and gave the order to fire, the terror-stricken Japanese raiders fled. Then the human soldiers hiding in ambush leaped up and slew them all.

In 2003, during the Iraq War, President George W. Bush turned down Morocco’s offer of 2,000 monkeys from the Atlas Mountains trained to deactivate and detonate land mines. In ancient times no one expressed qualms about “weaponizing” animals out of sympathy for the creatures. But today, these controversial examples open discussion of the ethics of forcing animal “volunteers,” from dogs to dolphins, to perform violent or dangerous acts in wars perpetrated by humans.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); “The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times” (2011); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

May 4, 2012

A whiff of trouble: Arnau of Vilanova’s uroscopy advice

By Marri Lynn (W&M Regular Contributor)

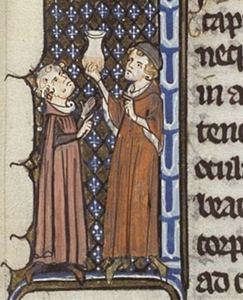

14th century uroscopy underway.

Recognizing that a medieval physician’s skills started with his ability to auger urine, many a patient chose to run diagnostic exams of their own. A ready litmus test was at hand: a sneaky game of pee-swap.

Prospective clients or ailing patients often sent an intermediary with ‘their’ urine in their stead, making it impossible for the doctor to see and assess the patient directly through other visible symptoms. Presented with a flask of mysterious liquid and the poker face of a healthy comrade of the ill, the physician was at risk of discrediting himself spectacularly.

The urine swap trick was intended as a test of a doctor’s learnedness, confidence, and powers of perception. For the patients concerned, good uroscopy skills in their physician, or lack thereof, could mean the difference between a precise diagnosis and helpful medication to follow, or a costly and potentially deadly blunder.

Arnau of Vilanova, a twelfth-century polymath and physician, was rather familiar and frustrated with these attempts to make fools of honourable physicians. In a tract on bedside manner, he laid out no less than nineteen itemized pieces of advice for addressing the commonest types of tricks, from the replacement of a patient’s urine with that of a relative’s of the opposite sex, to being confronted with animal urine or even white wine.

Arnau advises, first, to aim for the weakest link: the trickster himself, or the go-between who’s brought the urine forward. “You must look at him sharply and keep your eyes straight on him or on his face,” Arnau writes, “and if he wishes to deceive you he will start laughing or the color of his face will change…”

There is only one correct response for any physician affronted with such flagrant deception: “…you must curse him forever and in all eternity.”

Note well that the recommended admonishment for those who try to smuggle white wine in place of urine is, instead, “get away and be ashamed of yourself!”

More interestingly, Arnau advises that physicians should covertly sniff the suspect liquid by getting a small drop on the finger and then pretending to blow one’s nose. It’s curious that he suggests this subterfuge instead of advising his readers to openly sniff, quaff, or look at the liquid at length. Presumably Arnau didn’t trust that the appearances and odours of these random liquids would be obvious enough to every reader. Or perhaps the reputation of physicianhood had such high expectations (or honours?) upon it that a full, sommelier-like urine analysis was preferably not to be performed in front of prospective and dubious clients.

When confronted with a more poker-faced customer and a liquid more mysterious or less odious than wine, Arnau gave advice that would bring a smile to the face of Dr. Gregory House. To preserve the proper medical air of authority, the physician was instructed to ask leading questions in the hope the uneducated client would accidentally reveal the real source of the liquid. But if the answers were vague, or the individual donated false information to further trick the physician, Arnau instructed his peers to gain a little leverage and re-assert authority by using flashy medical terminology that would leave the client blinking in ignorance. That would, Arnau assured, put the upstart in his place and remind him that a physician’s intellect could not be tested by his ilk.

Arnau’s advice reveals more than just the frustrations and tactics of doctors attempting to avoid the pitfalls of patients engaging in a little research before purchase; here is evidence of the tenuous public position held by scholastic medicine’s truth-claims, as well as its effect on what constituted professional training. A physician couldn’t, or shouldn’t, rely on his knowledge of urines alone to combat patient subterfuge. Perception, deception, tact, and psychology went hand-in-hand with the uroscopy flask.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently studying French, while freelancing as a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

May 1, 2012

The Merry Month of May?

I once wandered into a pagan festival in Edinburgh by accident. A friend and I had curiously followed the crowds and sound of drumming, ending up at Calton Hill Beltane. People painted blue or red danced past by torchlight, then a group of women in white. A marriage-like ceremony between a white-clad woman and a half-naked man concluded the procession. This was a celebration of spring, fertility, and controlled unruliness.

Bonfires, dancing around the maypole, sexual play: these fertility rituals were typical of May Day (also Beltane and Walpurgisnacht) across early modern Europe, which took place from April 30 to May 1. The garlanding of a May Queen with flowers and leaves represented healthy crops and young women danced around phallic symbols (maypoles).

Maypole Dance at 25th Anniversary Fete, Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Early modern Europe was an agrarian world with over 90% of the population living rurally. People anxiously watched for omens about weather and crops. A snowy February meant a fine summer; rain on Palm Sunday meant little hay. People used magical and religious means to control their environment, especially by reinforcing thresholds. By placing a shoe in the chimney, a householder hoped to keep evil from entering the house. To drive evil from their parishes, priests walked the boundaries.

Liminal times of year – points of transition – were considered risky, but powerful. Good Friday was a bad day to shoe horses or plant crops, but bread made then might cure all ills. In the liturgical calendar, Good Friday marked Christ’s death and the wait for his resurrection. May Day was a dangerous in-between period, too. Crops planted, people could only wait and hope. Despite the fertility rituals, couples who married or children conceived during May were thought to be unlucky.

The boundaries between natural and supernatural worlds were considered weak during liminal times. Germans believed that witches gathered together on Walpurgisnacht, and, more generally, people thought that spirits moved between the worlds all month. Sound familiar? The May celebrations mirrored those exactly six months away: Halloween and All Saints Day.

The merriness of May Day was real, but had a dark side. It was a perilous time when the dead walked and new crops were vulnerable. Modern May Day festivals like the one in Edinburgh are merely celebrations today, but once upon a time had a much more important purpose: survival.

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and recently taught a course on natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe.

April 22, 2012

Images of Invisible Ink

By Kristie Macrakis (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

When Marc Merlin, the Atlanta Science Tavern host, asked if I’d be willing to write a blog for Wonders & Marvels, I jumped at the chance. I always thought of my current topic – invisible ink – as a wonder, a marvel of nature. It would fit perfectly. But then he added: “make sure to include a nice image.”

A nice image! My mind started racing. It’s not that the history of invisible ink doesn’t have images; it does (and they are not a pile of blank pages!) You can think of the well-known ones yourself: a lemon juice written piece of paper with the letters scorched brown by a candle or lamp, a yellowed piece of paper from the American Revolutionary War with developed invisible ink, letters that fluoresce under a UV light known to many school children etc. etc. etc.

But the slice of history I wanted to focus on was elusive when it came to finding an image. I have imagined it many times. And this image is a real marvel, an awesome sight.

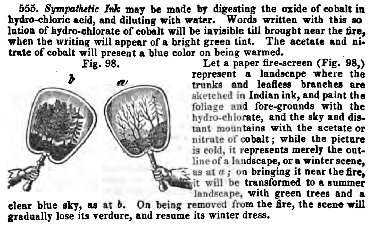

Do-it-yourself invisible ink paper fire-screen, "Chemistry, Collegiate Institutions, Schools, Families, and Private Students" (1857)

In Eighteenth Century Paris, changeable landscape fire-screens for fireplaces became all the rage. A barren winter landscape with tree trunks and branches was painted on a fire-screen with ordinary India ink. The artist then painted a solution of cobalt chloride on the screen to create lush shrubs and greenery. The cobalt was invisible initially, but as soon as the heat from the fire reached the screen, the barren winter landscape magically turned into a verdant green landscape. When the heat source is removed, the landscape becomes barren winter again. You should try it; it is truly magical and beautiful.

Then there’s the story behind this special effect of the 18th and early 19th Century. In the early 1700’s Jean Hellot, the French industrial chemist and inspector general of dyeing, climbed the hills of Saxony in search of this magical rock. He had gotten the tip from a mysterious German alchemist (a Dorothea Walchin or Wallich). The mountains and hills of Schneeberg were alive with silver and cobalt. But extracting cobalt was not an easy business when spirits seemed to inhabit forests, caves and mountains. The German word “Kobold” means goblin, and a miner’s kobold was a mischievous invisible spirit that haunted subterranean places like mines.

But Hellot persisted and was the first to write a scientific article on this new cobalt invisible ink in 1737 for the proceedings of the Academy of Sciences. The only problem is that Hellot himself is a bit invisible. Since he was a practical chemist he is not as well known as the chemical revolution luminaries like Antoine Lavoisier. And the worst part is that I can’t find a painting of Hellot. I don’t know what this invisible ink pioneer looks like!

So this brings me to my plea. If anyone has information or information leading to an image of the changeable landscape fire screens or an image of the elusive Jean Hellot, please let me know!

Kristie Macrakis is a historian of science and of espionage. Her research interests include the science in Nazi Germany and Post-War Germany, Cold War espionage including the East German Ministry for State Security. (See her Seduced by Secrets , Cambridge, 2008). Kristie is currently writing a book on the history of invisible ink from ancient to modern times.

April 18, 2012

The World’s First Aviator?

By Pamela Toler

Photo courtesy of the Smithonsian Institute

‘Abbas Ibn Firnas is not well known in the west but he’s a hero to little boys and aviation buffs throughout the Arab-speaking world.

The Andalusian scientist was court poet and astronomer to Abd al-Rahman III in the days when Cordoba was the wealthiest and most civilized city in Europe. Like many Muslim scientists of the ninth and tenth centuries, he was a polymath. He produced a revised version of al-Khwariizmi’s astronomical tables that was later important in the development of European astronomy. He built an observatory, invented a metronome, and learned how to cut crystal. None of that makes him stand out among the polymaths of the Islamic golden age.

Ibn Firnas’s fame depends on one moment in his productive and accomplished career. In 875 CE, at the age of sixty-five, Ibn Firnas tried to fly. Using a hang-glider made of feathers and wood that he built after hours of observing birds in flight, he leapt off the roof of the Rusafa palace in Cordoba. By all accounts, he flew for several minutes, gliding on the air currents like a raptor. He as able to adjust his altitude and change direction, but he hadn’t made any provision for landing. Badly injured in the inevitable crash, the scientist was still alert enough to explain that he knew what he’d done wrong. He hadn’t paid enough attention to how birds use their tail feathers.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.