Holly Tucker's Blog, page 80

July 9, 2012

Midwives as murderers in 17th century London

By Helen King

In my last post for Wonders & Marvels, I introduced you to my favourite historical  character, the ‘Popish midwife’ Elizabeth Cellier. When I was researching her for the first time some years back, I came across another midwife who was in London at precisely the same time: Mary Awbry, or Hobry. Like Elizabeth, Mary was accused of a crime, and appeared before the Old Bailey. Unlike Elizabeth, Mary came to a sticky end; her story is recounted in a pamphlet entitled ‘A Hellish Murder Committed by a French Midwife, on the Body of Her Husband, Jan. 27, 1687/8 for which she was Arraigned at the Old-Baily, Feb. 22, 1687/8, and Pleaded Guilty, and the Day Following Received Sentence to be Burnt’.

character, the ‘Popish midwife’ Elizabeth Cellier. When I was researching her for the first time some years back, I came across another midwife who was in London at precisely the same time: Mary Awbry, or Hobry. Like Elizabeth, Mary was accused of a crime, and appeared before the Old Bailey. Unlike Elizabeth, Mary came to a sticky end; her story is recounted in a pamphlet entitled ‘A Hellish Murder Committed by a French Midwife, on the Body of Her Husband, Jan. 27, 1687/8 for which she was Arraigned at the Old-Baily, Feb. 22, 1687/8, and Pleaded Guilty, and the Day Following Received Sentence to be Burnt’.

‘Burnt’? Yes, Mary died for her crime. It wasn’t ‘just’ murder: it was the murder of her husband Denis. And it wasn’t just that, either; she dismembered him and hid pieces in various locations around London. And it wasn’t just dismemberment; she used her young son to help conceal the bits. The image of a midwife as murderer was a potent one. This was, indeed, a ‘hellish’ crime.

It is clear from Mary’s evidence to the court that she had been the victim of domestic violence from her impecunious husband one time too many. On the night of the crime Denis returned home drunk, and raped her. But she could not claim this was a crime of passion because she waited until he was asleep before strangling him. It also didn’t help her case that, before the fateful night, she had been heard by witnesses to say ‘I must kill him’.

As she was French – apparently one of many Huguenot immigrants to London at this time – what she said was in fact ‘Il faut que je le tue’. Mary had married Denis Awbry, a Catholic, only four years before she killed him, and her previous name comes up in passing in the account of her trial: Desermeau. This means that her son John, her accomplice, must have been from an earlier relationship.

We know of a midwife called Mary Des Ormeaux from another source, the 1680 licensing records of the Anglican church, in which she provided testimonials from five witnesses and was licensed to serve the French community in London. At this point her husband was a jeweller called Daniel. After I first read about Mary Awbry, I came across Mary Des Ormeaux in the 1991 PhD thesis of Doreen Evenden. There, Mary featured as a model midwife, so I contacted Doreen to let her know my suspicions. Doreen and I spent an afternoon in the British Library reading the account of Mary’s trial together. Doreen was so horrified at what had happened to ‘her’ Mary that she cried out, and a librarian had to come over to threaten us with expulsion! Doreen was persuaded, but neither of us could find any more evidence to tell us how the Huguenot Mary Des Ormeaux ended up with the Catholic Denis Awbry who treated her so badly that she killed him.

Motto 1: maybe two characters you’ve come across in history are the same person: women change their names, and we need to be alert and look out for the connections.

Motto 2: it can all end in tears – and flames.

- the image shows a modern representation of the Huguenots’ flight to England, from the French Protestant church in Soho Square, London -

Further reading:

Doreen Evenden, The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Frances Dolan, Marriage and Violence: The Early Modern Legacy (Pennsylania University Press, 2008)

July 6, 2012

Names of Dogs in Ancient Greece

Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels Contributor)

Imagine you live in ancient Greece. You are about to choose a new puppy. What should you call it? There was a science to choosing and naming a dog in classical antiquity.

Which is the finest puppy in a litter? Like moderns, the ancients looked for an adventurous and friendly nature, but one test for selecting the pick of the litter seems rather heartless today. Let the mother choose for you, advises Nemesianus, a Roman expert on hunting dogs. Take away her puppies, surround them with an oil-soaked string and set it on fire. The mother will jump over the ring of flames and rescue each puppy, one by one, in order of their merit. Other signs of an excellent hound are large, soft ears, instead of small and stiff. Upright ears are fine, but the best ears flop over just a bit. A long, supple neck adapts well to a collar. The chest should be broad, shoulder blades wide apart, and hind legs slightly longer than the front, for chasing rabbits uphill. The dog’s coat, whether long or short, can be any color, but the fur ought to be shiny, dense, and soft.

Training a young dog begins at 20 months, but a puppy needs a good name right away. Xenophon, a Greek historian who wrote about hounds in the fourth century BC, maintained that the best names are short, one or two syllables, so they can be called easily. No Greek hounds were saddled with monikers like Thrasybulus or Thucydides! The meaning of the name was also important for the morale of both master and dog: names that express speed, courage, strength, appearance, and other qualities were favored. Xenophon named his favorite dog Horme (Eager).

Atalanta, the famous huntress of Greek myth, called her dog Aura (Breeze). An ancient Greek vase painting of 560 BC shows Atalanta and other heroes and their hounds killing the great Calydonian Boar. Seven dogs’ names are inscribed on the vase (some violate Xenophon’s brevity rule): Hormenos (Impulse), Methepon (Pursuer), Egertes (Vigilant), Korax (Raven), Marpsas, Labros (Fierce), and Eubolous (Shooter).

The Roman poet Ovid gives the Greek names of the 36 dogs that belonged to Actaeon, the unlucky hunter of Greek myth who was torn apart by his pack: among them were Tigris, Laelaps (Storm), Aello (Whirlwind), and Arcas (Bear). Pollux lists 15 dog names; another list is found in Columella. The longest list of suitable names for ancient Greek dogs—46 in all—was compiled by the dog whisperer Xenophon. Popular names for dogs in antiquity, translated from Greek, include Lurcher, Whitey, Blackie, Tawny, Blue, Blossom, Keeper, Fencer, Butcher, Spoiler, Hasty, Hurry, Stubborn, Yelp, Tracker, Dash, Happy, Jolly, Trooper, Rockdove, Growler, Fury, Riot, Lance, Pell-Mell, Plucky, Killer, Crafty, Swift, and Dagger.

Alexander the Great honored his faithful dog, Peritas (January), by naming a city after him. Greek and Roman writers remind their readers to praise their canine companions. Arrian, the biographer of Alexander the Great who also wrote a treatise on hunting, says one should pat one’s dog, caress its head, pulling gently on the ears, and speak its name along with a hearty word or two—“Well done!” “Good girl!”—by way of encouragement. After all, remarks Arrian, “dogs enjoy being praised, just as noble men do.”

July 4, 2012

Pipes, Reins, & the Cerebral Winepress: Mechanical Metaphor in Vesalius’ Fabrica

By Marri Lynn (W&M Regular Contributor)

A woodcut from the Fabrica.

In the thousands of years of medical history preceding CAT scans, X-rays, and endeavors like the Visible Human Project, medical professionals often relied on two-dimensional drawings to inform their visualization of the inner workings of the human body. But drawings were often expensive to reproduce even with the advent of the printing press, and came with their own difficulties of representation. More often than not, medical professionals relied on the incredible power of their own imaginations to replace or augment these images.

Metaphor fit uniquely into their intellectual toolkit. Our word ‘metaphor’ comes to us through Old French, originally from the Greek words meta and phero. Meta means “between,” and phero means “to carry.” The resulting meaning is, then, “to carry [a concept] between.” Modern cognitive scientists have recognized the importance of conceptual analogy in our mental processes; some, like Douglas Hofstadter, have even gone so far as to say that “analogy is everything.”

Metaphors abound in the De Humani Corporis Fabrica, a well-known and stunningly illustrated 16th-century anatomy book by the anatomist Andreas Vesalius. I was particularly struck by his use of mechanical metaphors, and their implications for both Vesalius’ intellectual inheritance, and pre-modern anatomy’s handling of analogies. Mechanistic imagery is often considered a child of industrialization, but Vesalius shows us that in fact, the analogy of body-as-machine was alive and well centuries before. Indeed, it was a brainchild of antiquity, and a set of metaphorical imagery that Vesalius inherited and expanded upon to good effect.

Vesalius described veins, arteries, and nerves as hollow tubes, “like a pipe.” The metaphor wasn’t simply a visual comparison, but rather, a mnemonic for their functions in the body. In Greek medicine, the arteries were said to convey the ‘vital spirit,’ while the nerves conveyed ‘animal spirit.’ The Latin word spiritus which Vesalius used to describe these animating fluids derived from the Greek pneuma, or ‘breath,’ from which we get our word pneumatics. The functional meaning – air giving motion – would have been immediately clear to one of Vesalius’ educated readers. The Hellenistic world had many automata, self-animating toys and devices which made use of water or steam to produce motion. These, too, persisted in Vesalius’ world. It’s believed that a 15” high clockwork monk, currently held in the Smithsonian Institution, was designed by Juanelo Turriano for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V – the very same man to whom Vesalius dedicated his Fabrica.

In his use of moving metaphors, we can really see Vesalius’ attempt to get his readers to think of the body dynamically while studying anatomy; something which his two-dimensional images could not do on their own. For example, trying to describe the potential for rotational movement of the femur, or thigh bone, he writes, “It is as if you took a stick between your two extended hands and rotated it by drawing them alternately forward and backward: the ninth and tenth muscles correspond to your hands, and the femur might well be likened to the stick.” In his attempt to describe the functional movement of ligaments, he writes, “Charioteers imitate this cunning device of Nature by the rings that they put on the yokes of horses so as to control, by means of a long rein passed through the ring, horses on which they are not actually sitting.”

The example of the ‘cerebral winepress’ best represents Vesalius’ conditional acceptance of his metaphorical heritage. In the 4th century BCE, the scientist Herophilos named the confluence of sinuses at the back of the skull the lenos, or winepress. In the Latin-speaking world, this became the torcular Herophili, or Herophilos’ winepress. This confluence of sinuses sent blood into the different sinus channels “like wine from a winepress,” a motion easy to visualize through that analogy. Vesalius refers to this minor anatomical detail specifically in order to address the fact that Galen applied this name to not one part of the confluence of sinuses, but two. A sentence later, Vesalius makes his unique philosophy on the utilization of these inherited metaphors fairly clear. He states frankly that he did not care what specific part the name was applied to, “provided that you do not pervert the system of the cerebral sinuses and vessels.” Vesalius’ text exhibits an awareness and care about the semantic debates within medicine, without getting overwhelmed by them. Observation came first, metaphor second, and then only in a useful capacity.

Vesalius, like his anatomist forefathers, saw the body as a describable, mentally accessible, and comprehensible entity – an attitude which aided in the demystification of the inner body. Vesalius conceived of the body as a whole formed by moving parts, and implied that man’s engines and inventions were in imitation of Nature, and not the other way around. In other words, Vesalius, like his medical forefathers, saw innate principles of physical design in the operations of the body, which mankind had unknowingly imitated in his technological inventions. Through comparing the two, he populated the idea of the body with functional machines and architectural forms, rendering a mysterious world suddenly as discoverable as a new city.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently a freelance a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

June 30, 2012

Why we love to read (and write!) novels about queens: Part II

by Stephanie Cowell

There are powerful queens (Elizabeth I, Cleopatra, Catherine de Medici, Isabelle of Castile, Eleanor of Aquitaine) or queen victims of kings and minis

ters (Mad Joana, Caroline, Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard). They often have a great deal of money, fantastic dresses and jewels, and the adoration of the multitudes.

ters (Mad Joana, Caroline, Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard). They often have a great deal of money, fantastic dresses and jewels, and the adoration of the multitudes.

Imagine never having to buckle your own shoe or sandal, sixteen attendants lounging around (and never a moment’s privacy) and 5000 dresses in the wardrobe (Good Queen Bess!) It is a great life except for having your head cut off, or having your best friend conspire against your life or being divorced for barrenness. It is an adventurous life to read about after a day of laundry, children or the demands of an office….but there was certainly no job security.

Since I wrote the first part of this article a few months back, many new novels about queens have taken their place on bookshelves. Hilary Mantel’s novel about Anne Boleyn Bring Up the Bodies has been published to spectacular reviews and my friend C.W. Gortner has triumphed once again with making a sympathetic human being out of the Isabelle who sponsored Columbus in The Queen’s Vow.)

Of Anne Boleyn, Mantel writes that “she seems to embody nightmare: she’s the seductress, the poisoner, the woman who makes her man impotent with one poisoned glance.” And I always felt she was a victim!

I asked prolific novelist Michelle Moran about why we love to read and write about Queens. She commented, She says, “Personally, I like to read about queens who had to overcome great obstacles to either achieve power or remain in power. What made them different? Often it began with their birth. But not always. Gosh, so many great subjects and so much material still left to mine!” She, like several other fine novelists, is drawn back two thousand years to Cleopatra but her upcoming novel is about Napoleon’s second wife whom he married when poor Josephine proved barren. It’s called The Second Empress: A Novel of Napoleon’s Court.

Christy English, author of two novels about Eleanor of Aquitaine (To be Queen and The Queen’s Pawn) told me, “The queens of the past show us what is possible in an imperfect world. Women like Eleanor of Aquitaine defy the odds in their lifetimes, opening doors that should remain closed, fighting battles that seemingly cannot be won, and yet, they win them. This is why queens are so inspiring to me.”

Eva Stachniak tackled the most fascinating Empress of all in her novel The Winter Palace: A Novel of Catherine the Great. She said, “Those with trappings of power attract us perhaps the same way actresses do. We think of their lives as filled with glamour. Sometimes we are right, and sometimes the real women locked in the golden cages are truly unhappy. Again, not unlike the heroines of the silver screen. Even Catherine the Great had to face some limitations. An unwanted pregnancy stopped her from assuming power at once. She could not command troops in battle.” (Indeed!)

Anne Easter Smith, author of Queen by Right, adds, “If readers have noticed, most novelists choose to write about queens with chutzpah or those who have a tragic story to tell. I have never read a novel about Caroline of Ansbach, Mary of Modena, Anne of Denmark, or Caroline of Brunswick. Dare I say that in today’s market, editors are looking for those marquee names to sell a book, and that’s why you get three thousand novels about Anne Boleyn or Mary, Queen of Scots?”

The gifted Sherry Jones has written a poetic novel called Four Sisters: All Queens. Four queens in one novel! I had to look at it! And when I e-mailed her, she was kind enough to answer my question: Why do we love to write and read about queens?

Sherry said, “We love books about Queens because, deep down inside, we all want to be one. What’s not to covet? A fabulous wardrobe; servants taking care of your every need; every meal a gourmet feast; pomp and ceremony; celebrity status; respect and honor; the chance, perhaps to make a positive difference in the world. These women’s stories inspire us as women to strive for our own highest potential, to claim our own power – they remind us that we are all, truly, Queens.”

Does anyone have another Queen to suggest as a subject for a novel? Comment below! I have mine and am making notes here and there, but alas! she was fat, dumpy, over fifty and more into meddling in the marriages of her children than ruling. Guess who!

__________________

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

Imagining Vampires

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

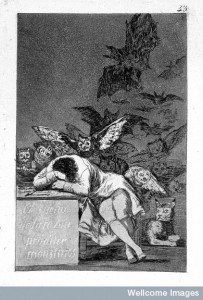

Goya, The Sleep of Reason (Credit: The Wellcome Library)

Vampires were the flavour of the month, with two very different types of vampires on show: the staked skeletons of an archaeological discovery and the sexy beasts starring in a new season of a certain TV programme.

The division of these two types can be traced to the eighteenth century. The Ottoman Empire and Kingdom of Austria signed the Treat of Passarowitz in 1718, extending Austrian control into modern-day Romania and Serbia. Strange stories came from the borderlands: corpses resurrecting and causing other people to die suddenly. The Western public eagerly the tales of the exotic East.

Folkloric belief in vampires never really caught on in the West, instead appearing primarily in literature (eg. Heinrich August Ossenfelder’s poem, “The Vampire”, 1748). The western tradition of revenants and blood-suckers referred to ghosts, witches, and unpopular political figures; western folklore had no room for the soulless walking corpses, but vampires would add an erotic frisson in gothic horror.

From the outset, the “Credibility of Vampyres” was unlikely in Western Europe, given the growing cultural tension between reason and imagination, natural explanations and superstition. The mark of an educated man was to find rational, natural explanations for observed phenomena, by contrast to the continued reliance on supernatural explanations attributed to the lower classes, foreigners, and women (thought to be prone to flights of fancy). The Gentleman’s Magazine (vol. II, May 1732) insisted that it was impossible for dead bodies to behave this way and atributing it to the Devil would only “superinduce new Impossibilities”. The conclusion? “We must disbelieve it, or renounce our Reason.”

Epidemics, however, were an ongoing concern. Medical men and civic authorities monitored patterns in the hopes of being able to prevent epidemics. It is within this context that Augustin Calmet, Benedictine monk and biblical scholar, collected accounts of supernatural events in his Dissertations sur les apparitions, des anges, des démons et des esprits, et sur les revenants et vampires de Hongrie, de Boheme, de Moravie et de Silésie (Paris, 1746; English translation, 1759).

The concern that emerges was the possibility of a new (to the west) contagious disease, or worse yet, that an epidemic of excess imagination. Dutch newspaper The Gleaner reported in 1733 that the problem was a “disturbed imagination” amongst the “ignorant and credulous”, caused by a poor diet that made their blood heavy. The “poison” could then be transmitted to others just like rabies. More likely, Calmet suggested, was the direct action of imagination on individual bodies. As physicians knew, people could be tricked into seeing and hearing what was not there—and extreme fear could kill.

In a section on ‘epidemical fanaticism’, Calmet referred to epidemics in which physicians saw fear as causing more problems than the disease. This, then, seemed to the main threat: imagination was always potentially dangerous, but imagining vampires could be fatal. A problem that modern vampire fans might want to keep in mind…

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and recently taught a course on natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe.

June 22, 2012

Coney Island Sea Rabbits & Benbecula Mermaids

By Sonya Collins (Atlanta Science Tavern contributor)

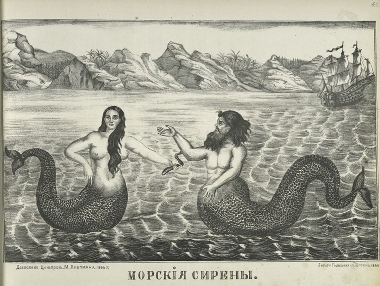

Mermen - Lubok style

I saw a sea rabbit off the coast of Brooklyn in the summer of 2008. “Dr.” Takeshi Yamada stepped off the Coney Island boardwalk to wander among sunbathers and castle-builders offering them the chance to pet the creature. Yamada, dressed in a black three-piece suit, looked like a “doctor” who might’ve sold snake oil to unwitting tourists strolling that same boardwalk beneath parasols the year it opened in 1923.

Tucked under Yamada’s arm was a fuzzy creature with the upper body of a rabbit and a long mermaid-like tail. It was lumpy and appeared to be losing fur by the fistful, and though my fellow sunbathers and I knew better than to believe in sea-dwelling rabbits, somehow we couldn’t be sure.

We looked at the rabbit and then each other, heads inclined but unwilling to give voice to the words inside our heads: Is that real? There wasn’t unanimous laughter, or “How’d you make that?” In spite of ourselves, for at least a moment, we were willing to believe.

But why? What makes reasonable people willing to believe they’ve seen Nessie, Big Foot or – perhaps a distant cousin of the sea rabbit – a mermaid?

Sometimes, says anthropology researcher Nick Sucik, it just takes one outlying circumstance. Sucik has lived among diverse people to study the mythical creatures they believe in and to understand why.

The year I saw the sea rabbit, Sucik was on the Scottish island of Benbecula, searching for a storied mermaid grave. You’ll have to read about the outcome of Sucik’s search in the UK’s Fortean Times in a couple of months, but he did share his thoughts as to why an entire island came to believe they’d seen a mermaid.

The Benbecula Mermaid story was first recorded in the Carmina Gadelica, a multivolume collection of Scottish prayers and folktales compiled by Alexander Carmichael in 1910.

Carmichael wrote: Some seventy years ago, people were cutting seaweed at […] Benbecula. […] One of the women […] saw a creature in the form of a woman in miniature, some few feet away. Alarmed, the woman called to her friends, [who] rushed to the place.

The creature made somersaults. Some men waded into the water […], but she moved beyond their reach. Some boys threw stones […]; one […] struck her in the back. A few days afterwards, this strange creature was found dead […] nearly two miles away.

[Her upper body] was about the size of a well-fed child […], with an abnormally developed breast. The hair was long, dark, and glossy; the skin was white, soft […]. The lower […] body was like a salmon, but without scales. Crowds, some from long distances, came to see this strange animal, and all [agreed] that they had gazed on [a] mermaid.

Mr. Duncan Shaw, […] sheriff of the district, ordered a coffin and shroud be made for the mermaid […]. The body was buried in the presence of many people […]. There are persons still living who saw and touched this curious creature, who give graphic descriptions of its appearance.

The mermaid’s funeral is said to be one of the most widely attended events in Benbecula’s history. “People rarely ventured away from their cottages,” Sucik said. “But now they traveled from all over the island.” That the sheriff ordered a coffin and shroud – costly items – was also noteworthy. The “mermaid” – an unbaptized foreigner – “was given a celebrity burial,” Sucik said.

Images of mer-people span cultures and history from the ancient Greek Triton to Inuit carvings of a fish with a woman’s face, Sucik says. Many written accounts of mermaid sightings are later chalked up to “cases of mistaken identity.” What settlers described as a merman off the coast of Virginia in 1676 historians now believe was a bearded seal described by people who had never seen one before.

“You’re seeing a creature in the water with the upper body bobbing upright above the surface. It’s not moving like an animal in the way that you’re used to, but swimming towards you, facing you, with those forward-facing eyes. For someone who’s never seen a seal, it has a presence that reminds you of a person,” Sucik says.

Other accounts of mermaids, Sucik is certain, have simply described women swimming in the nude. But because it was uncommon in the times of the sightings for people to know how to swim, the sight of a human swimming, combined with the shock of that human being a naked woman, pushed the viewer to take such a leap as to believe he’d seen a mermaid.

In these descriptions, the maidens always disappear under the water when spied by an onlooker. But if you were swimming naked, wouldn’t you?

“Especially in traditional societies, like on the islands, it’s so easy and common for folks, instead of looking for a more plausible explanation, to take huge leaps,” he says.

Sucik has traveled to Native American reservations to understand one group’s belief in a winged snake and another’s belief that an African lion walked among them here in North America.

“A lot of these stories have a mundane explanation that we’ve taken out of context,” he says. “It all seems like innocent fun, but it gets to a point where people don’t believe in global warming or they think that vaccines give kids autism because they’ve been subscribing to this sort of pseudoscience.”

A Google search revealed to me that Dr. Yamada was the Dr. Frankenstein of taxidermy. His Brooklyn art studio is filled with faux-offspring of the oddest couples of the animal kingdom – an explanation only slightly less bizarre than just believing in sea rabbits.

Sonya Collins is an independent journalist covering health care, medicine and science. She is a regular contributor to WebMD and Yale Medicine Magazine and the editor of the Georgia Public Health News Bureau.

June 20, 2012

I Need Your Help—And a Giveaway!

In August I’m giving a talk at the SCBWI Summer Conference entitled “The Ten Commandments of [Writing] Historical Fiction [forYoung Readers].” Here’s a sample:

Thou shalt not repeat falsehoods. Don’t say that Columbus took his voyage west to prove that the world was round; don’t say that spices were used in the Middle Ages to prevent food from rotting. Both are false.

Thou shalt not show off. You found an intriguing fact—great! But if it isn’t necessary for your story, don’t cram it in.

Thou shalt remember that “historical” is an adjective; thou art writing fiction. Don’t forget character development, good pacing, interesting dialogue—everything that makes a story a good story, historical or not.

I have seven more (including the obvious, such as getting your facts straight) but maybe there are things that irritate others that haven’t occurred to me. So tell me, readers of historical fiction—what bugs you when you read a novel set in the past? What makes you roll your eyes and shut the book—or hurl it across the room?

Best comment received by July 20 earns its writer a copy of my young-adult historical novel Dark of the Moon!

June 18, 2012

An Islamic Map for a Christian King

by Pamela Toler

Most maps made in twelfth century Europe were based on tradition and myth rather than scientific information. The only practical maps were mariners’ charts that showed coastlines, ports of call, shallows and places to take on provisions and water. Roger II, the Christian king of Sicily, wanted a map of the known world that was a factual as a mariner’s chart. In 1138, he hired well-known Muslim scholar al-Sharif al-Idrisi to collect and evaluate all available geographic knowledge and organize it into an accurate picture of the world.

For 15 years, al-Idrisi and a group of scholars studied and compared the work of previous geographers. They interviewed the crews of ships who docked at Sicily’s busy ports. They sent scientific expeditions, including draftsmen and cartographers, to collect information about relatively unknown places.

Finally, al-Idrisi was ready to make his map. He began by making a working copy on a drawing board, using compasses to accurately site individual places. The final copy was engraved on a great silver disk that was almost eighty inches in diameter and weighed over 300 pounds. Al-Idrisi explained that the disk was just a symbol for the shape of the world: “the earth is round like a sphere, and the waters adhere to it and are maintained on it through natural equilibrium which suffers no variation”

Al-Idrisi’s map was accompanied by a descriptive geography that contained all the information his college of geographers had collected. Its formal name was Nuzhat al-Mushtaq fi Ikhtiraq al-Afaq, or The Delight of One Who Wishes to Traverse the Regions of the World. It was more commonly known as Roger’s Book.

In 1160, the Sicilian barons revolted against Roger’s son, William. They looted the palace and burned the library, including Roger’s Book. Not surprisingly, the silver map disappeared. Al-Idrisi fled to North Africa with the Arabic text of Roger’s Book. His work survived in the Islamic world, but it was not available in Europe again until the Arabic text was printed in Rome in 1592.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

June 16, 2012

Collaborative Research in the Humanities

Let me begin with a kind of provocation: however critical we humanists are of the ideals of authorial authority and genius, our practices of scholarship and the ways they gain legitimacy in the academy continue, even in this digital age, to be rooted in those outmoded 19th century ideals.

Rembrant: The Philosopher in Meditation

Edgar Allan Poe gives voice to the notion of genius I have in mind:

The true genius shudders at incompleteness–imperfection–and usually prefers silence to saying something which is not everything that should be said (Marginalia X).

Still today, we humanists shudder at incompleteness, protecting our ideas from the public, polishing them toward perfection in the private confines of the library or the book lined study. We prefer the silence of these spaces, nurturing our ideas until everything is said just right. Only then are we prepared, reluctantly, to reveal them to the world.

We begin by exposing our ideas at conferences to small groups of experts where they are challenged, questioned and, if the experts have just the right balance of generosity and grace, improved by virtue of thoughtful discussion.

We then return to our private, silent places, to nurse our wounded egos, celebrate what was well received, and further polish our ideas into brilliance, until they are prepared to be reviewed by two or three eminent figures, anonymous all, for a major university press. If deemed original, innovative, and ingenius enough to print, they will find their way into bound tombs to line the wall of another study, where another lone scholar will polish another idea toward perfection.

Poe’s genuis continues, even at this late date, to haunt humanities scholarship.

And yet, in a digital age, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Planned Obsolescence suggests, we humanists are learning to expose our ideas earlier to the insights of others; we are starting to collaborate and to listen; even from our libraries and studies, we are beginning to think and read and write in public. The great challenge for the humanities in a digital age is to transform a culture of genius into one of collaborative excellence.

suggests, we humanists are learning to expose our ideas earlier to the insights of others; we are starting to collaborate and to listen; even from our libraries and studies, we are beginning to think and read and write in public. The great challenge for the humanities in a digital age is to transform a culture of genius into one of collaborative excellence.

To do this, we need examples, not paragons of genius, but concrete attempts at collaborative public scholarship, and reflection on what fails and succeed in those attempts. For the past five years, I have sought to perform scholarship in public largely through blogging and podcasting on The Long Road and through the Digital Dialogue.

Below, however, I outline another, perhaps more modest, attempt to engage in collaborative research in the humanities. It is a short presentation, a Prezi in fact that I recorded as a Vimeo video, that illustrates how I have invited my undergraduate research assistants to collaborate with me at an early stage of research, one that had previously been marked by silent study.

The Research Circle from Christopher Long on Vimeo.

This attempt is not perfect, but it has allowed me to introduce undergraduate students to the research endeavor that so often unfolds in private solitude; and in the process, my research has been enriched. So in the spirit of opening these issues to a wider public, I welcome your thoughts and reflections in the comments section below, or on twitter @cplong, or wherever else you would like to offer an engaged response.

References

Edgar Allan Poe, “Marginalia [part X],” Graham’s Magazine, January 1848, pp. 23-24.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy. New York: NYU Press, 2011

June 14, 2012

A Nun’s Story–Lessons from History

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (W&M Regular Contributor)

It is not often that my research is topical. Most people feign polite interest when I tell them I study sixteenth-century Spanish convents. But with the recent controversy over the Catholic Church’s scrutiny of the behavior and activities of American nuns, the subject of female monasticism has enjoyed an unprecedented timeliness.

My goal in this essay is not to enter the twenty-first century polemic; I’m much more comfortable in the sixteenth century. I would offer, however, the following observation: that certain assumptions and even stereotypes undergird the remarks of some of the participants in the current debate. And here is where history can be so useful. Arguably, we root some of our modern interpretations of nuns in what we think convents were like in the premodern period.

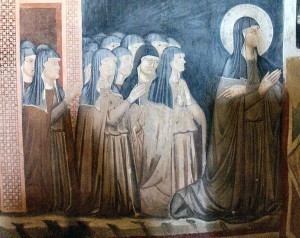

Clare of Assisi and some of her followers

* Convents were clearinghouses for un-marriageable daughters. Driven by the evidence of high marital dowries and other socio-economic factors, we imagine that convents served a necessary social function as a refuge for families with too many daughters or daughters who weren’t competitive on the marriage market. This assertion crumples, however, in the face of the fact that most convents also required a dowry. These dowries were smaller than secular dowries, but not inconsequential. Further, this assumption must be reconciled against numerous and varied expressions of religious vocation. The vast majority of nuns felt a spiritual calling to live in monastic communities.

* Convents were hotbeds of sexual scandal. Having accepted the notion that most nuns didn’t want to be there in the first place and certainly didn’t willingly take vows of celibacy, it is not much of a leap to imagine that they rebelled through sexual transgressions. This fine tradition owes much to Boccaccio’s Decameron (14th century) and similar literature; anti-religious Enlightenment polemics (18th century); and even nineteenth century Protestant re-interpretations of nuns as deviant renegades. It bears, however, little resemblance to reality and tells us more about the gender and religious politics of each of these eras than it does about the actual behavior of nuns. Overall, nuns devoted themselves to intercessory prayer, liturgical responsibilities, and social services like teaching and nursing. They had little time or interest in deviant behavior.

Aside from correcting popular perceptions, these two lessons from the historical record should also offer us some challenges as we examine the lives of contemporary nuns. As Mary Gordon remarked in a 2002 article based on her interviews with practicing nuns, “people look at me suspiciously when I talk to them about the happiness of the nuns I’ve spoken to.”* We struggle to comprehend the lives of women—premodern or modern—who would choose this life for themselves. The popular image of the nun suggests that women would only do this against their will and that they would engage in rebellious, transgressive behavior as a consequence. We owe the nuns—of both history and the present day—a better understanding of their lives than that.

* Mary Gordon, “Women of God,” The Atlantic Monthly (January 2002), 61.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.