Holly Tucker's Blog, page 78

September 6, 2012

Beauty Secrets of the Ancient Amazons

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

Galloping for miles on tough ponies, hunting, making war, marauding, and plundering, hot and dry in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter —life on the Scythian steppes was dirty, dusty work for nomad men and the women known to the ancient Greeks as Amazons. How did the saddle-sore Amazons and their male companions relax and tend to their bodies? For Scythians, bathing was a special occasion usually undertaken as a purification before funerals in the spring.

The Greek historian Herodotus (ca 450 BC) describes the Scythian-style toilette. Their unusually refreshing sauna sounds like a New Age spa treatment:

First the Scythians wash their heads with soap and water. But, notes Herodotus, they never wash their bodies this way. In order to cleanse their bodies, they fix in the ground three long sticks inclined towards one another to make a tipi-like booth. Large pieces of woolen felts are stretched over the poles, overlapping to fit as close as possible. Inside the tipi is a large stone bowl of red-hot stones. The men and women enter the felt tipi and toss handfuls of hemp-seeds onto the red-hot stones. (Cannabis grows wild on the steppes.) The smoke produces such a delightful vapor as no Grecian vapor-bath can exceed, remarks Herodotus. The Scythians shout for joy, and this intoxicating steam- bath serves them instead of a water-bath.

Then Herodotus divulges a recipe for an Amazon beauty mask.

The women make a mixture of cypress, cedar, and frankincense. They pound these ingredients into a paste on a rough stone, adding a little water. When this substance takes on a smooth, thick consistency, they cover their faces, and indeed their whole bodies, with the paste and retire for the night. When they remove the plaster on the next morning, comments Herodotus, a sweet odor is imparted to them and their skin is clean and glossy.

Today, all three of these ingredients are used in perfumes, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Cedar and cypress trees grow at high altitudes, as easily available to the Scythian nomads as local cannabis. Fragrant cedar and cypress oils have antiseptic qualities, helpful in fighting infection. Both are astringents, reducing oily, flakey skin, employed today against acne and dermatitis.

Small lumps of frankincense, the aromatic resin of Boswellia trees of the Arabian desert, would have been a precious trade commodity, available from merchants on the Silk Routes across Central Asia. It appears in ancient Egyptian recipes for beauty masks for toning and smoothing scars. Frankincense has antiseptic, anti-inflammatory properties, and is found in modern beauty products reputed to rejuvenate aging skin.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

September 2, 2012

WARNING: TOXIC! The Deadly Dead

By Lindsey Fitzharris (W&M Contributor)

When a person thinks of anatomical specimens from the past, he or she may think of disembodied remains floating in glass jars filled with alcohol. The Hunterian Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons in London is full of such specimens—unborn foetuses suspended in time as if still incubating in the womb; a hand, puffy and swollen from chronic lymphedema; a pock-marked face submerged in yellowing liquid.

But not all specimens were preserved in this way. Beginning in the middle of the 18th century, surgeons and anatomists began experimenting with arsenic and mercuric chloride as a means of preserving human remains.

Of course, arsenic had long been used for medicinal purposes before it was ever used for preservative purposes. It was prescribed in small doses for all types of disorders including tuberculosis, rheumatism, and syphilis. During the 15th century, William Wirthering remarked: “Poisons in small doses are the best medicines; and the best medicines in too large doses are poisonous.” [1]

Soon, however, surgeons and anatomists began recognising the preservative qualities of arsenic when creating dry mount displays from cadaverous remains. Mixtures of arsenic and soap were sometimes used to bathe the insides of a specimen in order to prevent decomposition and insect infestation. This method, invented by the French ornithologist Jean-Baptiste Becoeur (1718 – 1777), was especially popular with taxidermists. In fact, arsenical soap was used in museums around the world until the 1980s when it was finally banned due to its dangerous levels of toxicity.

In 1838, the French chemist, Jean Gannal, introduced a new method for preserving human remains using arsenic as a main ingredient. This was intended to allow anatomists to dissect corpses or prepare anatomical specimens without worrying about putrefaction or decay. He described his method as such:

[A] corpse is injected by the carotid with from five to seven quarts of the acetate of alumina at 20°, and containing in solution about two ounces (fifty grammes) of arsenic acid. Four days after this injection, if it is intended to prepare the large and small vessels, inject by the aorta half a quart of a mixture, equal parts, of the essence of turpentine and essence of varnish; finally, make a single cast of a hot injection of a mixture of suet and of rosin, in equal parts, coloured with cinabar [sic] for arteries, and with a black or blue colour for the veins. Then, the corpse, or the part of the corpse which it is intended to preserve, is prepared and dissected at leisure, according to the wish of the operator. [2]

By 1846, however, Gannal’s technique was outlawed in France. This was due in part to the fact that anatomists themselves were suffering the effects of arsenic poisoning.

Around the same time, anatomists also began using mercuric chloride as a preservative. The specimens were dipped in the solution, or painted with it. Mercury, as well as arsenic, had also been used for medicinal purposes during the early modern period, when its toxic qualities had not yet been fully recognised.

Around the same time, anatomists also began using mercuric chloride as a preservative. The specimens were dipped in the solution, or painted with it. Mercury, as well as arsenic, had also been used for medicinal purposes during the early modern period, when its toxic qualities had not yet been fully recognised.

Today, these types of anatomical specimens pose all sorts of dangers to museum staff who might be handling or interacting with these objects on a regular basis. Both substances can be absorbed through the skin. In cases of arsenic poisoning, severe headaches and confusion first appear, followed by discolouration of skin and fingernails, convulsions, stomach pain, hair loss and eventually death. (Find out here what happens if you ingest arsenic).

Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing whether arsenic or mercuric chloride is present simply by looking at a specimen. Many curators have turned these objects over to laboratories for testing, while others have developed their own methods for determining whether specimens are toxic. Nonetheless, the fact remains that any of the dry mount specimens lurking in museums and private collections are potentially hazardous, as was discovered in this episode of Oddities.

It turns out what you don’t know can in fact hurt you.

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon’s Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

2. J. N. Gannal, Preparations in Anatomy, Pathology and Natural History (1838), translated by R. Harlan (1840), p. 182.

August 23, 2012

Death by Crinoline

Cartoon in Punch Magazine, which frequently lampooned crinoline.

By Karen Abbott, W&M Contributor

In addition to smallpox, cholera, and consumption, Victorian era denizens had to consider the perils of crinoline, the rigid, cage-like structure worn under ladies’ skirts that, at the apex of its popularity, reached a diameter of six feet. The New York Times first reported the phenomenon of crinoline-related casualties in 1858, when a young Boston woman, standing by the mantel in her parlor, caught fire and within minutes was entirely consumed by flames—an unfortunate incident that came on the heels of nineteen such deaths in England in a two-month period. Witnesses, impeded by their own crinolines, were forced to watch the victims burn. “Certainly an average of three deaths per week from crinolines in conflagration,” the Times admonished, “ought to startle the most thoughtless of the privileged sex.” A similar tragedy occurred shortly thereafter in Philadelphia, when nine ballerinas burned to death at the Continental Theatre.

Non-fatal consequences of crinoline included entanglement in carriage wheels and being toppled by strong winds, often with mortifying consequences. Such was the case with Consuelo Montagu, the Duchess of Manchester, who snagged her hoops while climbing over a stile and landed upside down, revealing a pair of scarlet knickers. “I wish that people who wear crinoline could see the indecency of their own dress as other people see it,” wrote Florence Nightingale in her 1859 book, Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. “A respectable elderly woman stooping forward, invested in crinoline, exposes quite as much of her own person to the patient lying in the room as any opera dancer does on the stage. But no one will ever tell her this unpleasant truth.”

Nevertheless, crinoline offered some marked advantages over the traditional mode of dressing. It was much lighter and cooler than numerous petticoats suspended from a corseted waist, and, with the invention of the sewing machine in the 1850s, was able to be mass-produced. At the onset of the Civil War, resourceful Southern women discovered new and unexpected benefits of the contraption when they “ran the blockade,” circumventing President Lincoln’s strategy of preventing goods from reaching the Confederate states. One managed to conceal inside her hoop skirt a roll of army cloth, several pairs of cavalry boots, a roll of crimson flannel, packages of gilt braid and sewing silk, cans of preserved meats, and a bag of coffee—the contraband tally for a single crossing. Others tied sabers and pistols around the coils, smuggling small arsenals across the lines. Northern newspapers regularly described the “Secesh in petticoats” who artfully stuffed dozens of bottles of precious quinine beneath their skirts.

The backlash against crinoline intensified during and after the war. Ministers took to the pulpit to warn that wearing hoops was akin to renouncing Christianity. The fad was a “social evil” almost on par with smoking, spitting, and whoring, and women who wore crinoline did so with complete disregard for society. “We have seen the choicest flowers in our gardens and the most cherished plants in our greenhouses cut off by the hoop,” opined The Guardian. “Our wardrobes afford no room for our cloths, because the women of the family want more space than they can get. For five years we have no had room to turn ourselves round in our own homes.” The crinoline craze, or “crinolinemania,” as it was called, waned in the late 1860s, only to threaten revival thirty years later during what would become the heyday of the bustle (Mrs. Grover Cleveland was adamantly anti-crinoline), and again in the 1910s, just before the flapper would change women’s fashion for good. “Greatly daring are the women of today,” declared the New York Times in 1925. “And how they pity their ancestors in crinoline.”

Sources:

Books: Alison Gernsheim, Victorian & Edwardian Fashion. New York: Dover Publications, 1981; Susan J. Vincent, The Anatomy of Fashion. New York: Berg, 2009. Florence Nightingale, Notes On Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. London: Harrison, 1859.

Articles: “Christianity and Crinoline.” New York Times, September 15, 1858; “The Shocking Age.” New York Times, September 20, 1925; “Crinoline: A Real Social Evil.” The Guardian, October 16, 1861; “Mrs. Cleveland Against It.” New York Times, February 19, 1893; “The Perils of Crinoline.” New York Times, March 16, 1858; “Secesh in Petticoats.” New York Times, November 2, 1862.

August 22, 2012

An Unsung Hero of the Proto-Wiki

By Kelly Servick (Atlanta Science Tavern Contributor)

This story begins with an expert in his field donating his time to an ambitious encyclopedia project. The work would be an unprecedented collaboration of authors and editors, relying on new technology to distribute it on an enormous scale.

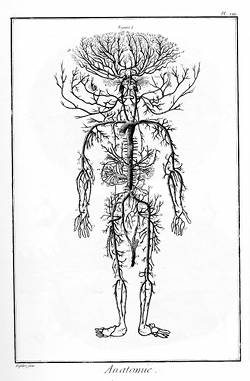

Anatomy plate from the Encyclopédie

If you’re picturing a devoted Wikipedian at his laptop, you’re only about 250 years too late. This beneficent expert was Louis de Jaucourt, the most prolific contributor to the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Jaucourt’s articles, many related to medicine and physiology, make up about a quarter of the text that embodied the ideals of the Enlightenment and helped spark the French Revolution. As production on Gutenberg’s printing press skyrocketed during 18th century, the encyclopedia championed empiricism and rang in the new age of science. The long-established medical doctrines of Galen, based on the theory of four bodily humors, finally crumbled.

The story of Jaucourt’s contribution begins with heartbreak. He completed medical school with no intention of practicing, then spent twenty years creating an enormous anatomy reference: the six-volume Lexicon Medicum Universalis. Given the climate of censorship in France, he put sole manuscript on a ship bound for Amsterdam. When the ship sank, it obliterated Jaucourt’s labor before it ever saw a printing press. (The next time auto-save fails you, imagine these reef-torn pages dissolving into a salty pulp.)

Jaucourt lived a quiet, solitary life, and was in his fifties when he was approached by Denis Diderot, father of the Encyclopédie and hero of the Enlightenment. Because Jaucourt was independently wealthy, he chose to write and edit full-time without compensation. Many contributors backed out when the Encyclopédie was outlawed in 1757, but Jaucourt went on writing in secret, accumulating ten volumes that were ready to publish when the ban was lifted in 1765. Diderot once remarked to a friend in correspondence, “Don’t worry that he will get bored of cranking out articles. God made him for that purpose.” In total, he wrote 17,266 articles, or about 8 per day for six years.

There is something charming about an outdated reference text, its obsolete knowledge conveyed with an air of certainty and garnished with outlandish illustrations. Even more charming is the idealism that compelled a small intellectual community to take on something so big. Yet this collaboration was truly the grandfather of every reference text to come, maybe Wikipedia most of all. Diderot referred to his team as “a society of men of letters and skilled workmen, each working separately on his own part, but all bound together solely by their zeal for the best interests of the human race and a feeling of mutual good will.” If 18th century France was an age of renewed faith in the competency and determinism of the layperson, Wikipedia is the ultimate test of that faith.

Unlike some scholars (and even other Encyclopédie contributors) who believed in a vital force that caused life to emerge from the physical structure of the human body, Jaucourt took a firmly mechanistic approach to biology. He saw the body as a collection of components interacting according to physical laws.

This is the approach we take to our encyclopedias these days. Unlike the compilers of Jaucourt’s day, we don’t have to organize knowledge into categories, imposing a tree structure on concepts that really interacted more like a network. Like in the mechanist model of anatomy that Jaucourt championed, these many little parts no longer need a vital force to organize them. They just need laws – search algorithms, zeros and ones – to build a flexible and dynamic body of knowledge. Then the prolific philanthropist-scholar can release his ideas into the world, never fearing they’ll flounder under reactionary governments or sink into oblivion in the North Sea. If a time warp somehow landed the French Lumieres in the digital age, I’d like to think Le Chevalier de Jaucourt and Jimmy Wales would hit it off.

Kelly Servick is an Atlanta writer preparing to start a grad program in science writing. She owes most of the knowledge in this post to altruistic Wikipedians.

August 20, 2012

Medieval Women as Physicians

Since at least Classical times,[i] European women have generally been in charge of their family’s health. In Medieval romances and lais, women are often portrayed as healers, not only in their homes but also in the community. Nursing the sick fell within the purview of the charitable work that nuns (and monks) were supposed to perform. The anonymous female author of a fourteenth-century Sister-Book described in detail the motherly care that her convent’s infirmarian, Anna von Wineck, took of her charges, saying that she served a woman with epilepsy

with devotion up to her death. She lovingly washed off with her own hands the sordid stuff and dirt that the illness caused. During the time when the sister was seized by this illness and yelled and foamed, [Anna] pressed her against her chest and patted her with motherly tenderness until she revived and the pain ceased . . .

She also served another sick sister, who similarly had lost the use of reason in her old age, as long as she lived with pious care. . . .

The third sister . . . had dropsy. Her body was terribly swollen, and she lay paralyzed for many years. The saintly sister . . . served her eagerly for God’s sake. The Lord permitted that this paralyzed sister–although she, too, was undoubtedly saintly–became so impatient as a consequence of the hardship of a lasting illness that she neither obeyed nor pleased one of her servants. She also could not speak with her [nurse] peacefully but often scolded her loudly.[ii]

By the twelfth century, medicine had become a topic taught at universities, side by side with traditional healing methods. One author says that although

women participated fully in the religious revival of [the twelfth and thirteenth centuries], they were excluded from formal higher education once the university became the standard seat of learning. The universities also guarded their monopoly on certain fields like medicine carefully.[iii]

“This upheaval” in education, turning medicine into an academic subject, says another scholar,

was difficult for many religious women because the shift in the world of medicine involved its transferal out of the monastic realm, which had allowed them to practice in various approved and non-threatening capacities for over five hundred years, into the university, where women were soon to be excluded altogether. Outside the monastery, secular women who practiced medicine lacked a religious vote of confidence in their work, so the crackdown on them was particularly severe. Men suddenly felt threatened by the number of secular religious women, or “lay healers,” whose “folk remedies” the general populace seemed to prefer over the scientific cures of the new university-trained doctors. By the fifteenth century, European women who practiced medicine had been thoroughly discredited on a large public scale; their healing arts had been tied to witchcraft and black magic.[iv]

Some historians assume that women’s exclusion from university-based medical training was total. The lack of regulation of medical practitioners practitioners led, according to one scholar who makes no attempt to remove scorn from his writing, “to the rise of a large number of uneducated practitioners, such as barbers, keepers of baths, and women of no particular training.”[v] Other historians posit that in the Middle Ages men performed diagnoses and prescribed treatments, and women carried out the practical application of their prescriptions, especially when the patient was female.[vi]

Yet since ancient times the record shows women referred to as medica, or doctor.[vii] And regulations such as a French edict of 1311 forbidding women to practice surgery unless “they have undergone an examination before the regularly appointed master surgeons of the corporation of Paris”[viii] demonstrates the existence of a mechanism, however rarely it may have been employed, to admit women to the practice of this most technically challenging area of the medical profession. An even earlier law passed in Sicily in 1244 says that a medical student “must swear never to consult with a Jew or with illiterate women”[ix]–implying that it was allowable to consult with women as long as they were not illiterate, hence educated.

Sicily and mainland Italy, especially the south, are something of a special case. Geographically, the region is within relatively easy reach of much of the Mediterranean, and by at least the tenth century, Greek, Roman, Arabic, and Jewish science (including medicine) had reached it. A school of medicine was established in the city of Salerno, and by the eleventh and twelfth centuries it had little competition for its primacy in the field of medical education. The school was secular and has been “credited with having arrested the decline of the science of medicine when learning as a whole was falling into decay.”[x] It was, by some accounts, the “first university of Europe in modern times . . . in this part of the world.”[xi] And what made it even more extraordinary was the presence of women as physicians and professors of medicine.

These female physicians were so well known that the mere mention of a salernitana would be enough to alert a medieval listener that the woman being discussed might have been trained in medicine. One of the characters in Marie de France’s lai “Deus Amanz” (“Two Lovers”) says: “In Salerno I have a relative, a wealthy woman with property. She’s been there for more than thirty years and has studied medical arts for so long that she knows a lot about herbs and roots.”[xii] Nobody in the lai reacts with surprise at the thought of a Salernitan women who has studied medicine formally.

Salerno was not the only medieval center with medical women. The University of Bologna boasted a professor named Alessandra Giliani, who performed pioneering studies of the functioning of the human circulatory system.[xiii] A twelfth-century translation into Latin introduced a Greek woman named Metrodora and her treatise on diseases of the womb (composed between the third and fifth century, making it perhaps the earliest medical writing by a woman in Europe), to Italy.[xiv] Medieval medical treatises by women include Mercuriade’s On Crises in Pestilent Fever and On the Cure of Wounds; Rebecca Guarna’s On Fevers, On the Urine, and On the Embryo; Abella’s On Black Bile and On the Nature of Seminal Fluid.[xv]

Perhaps the best-known medieval medical woman was Trotula, sometimes referred to in English as Dame Trot. More about her next month.

[i] Beryl Rowland claims that “in ancient Greece and Rome women seem to have practiced medicine on equal terms with men” and that “according to Tacitus, the practice of medicine [among the Germans] was entirely in the hands of women.” (Medieval Woman’s Guide to Health: The First English Gynecological Handbook. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1981, p. 2.)

[ii] Gertrud Jaron Lewis. By Women, For Women, About Women: The Sister-Books of Fourteenth-Century Germany. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1996, p. 243. Sister-books (Nonnenbücher or Schwesternbücher) are nine texts written by nuns of the Dominican Order in the first half of the fourteenth century.

[iii] Emilie Amt, ed. Women’s Lives in Medieval Europe: A Sourcebook. New York and London: Routledge, 1993, p. 5.

[iv] Marcia Kathleen Chamberlain, “Hildegard of Bingen’s Causes and Cures: A Radical Feminist Response to the Doctor-Cook Binary,” in Maud Burnett McInerney, ed. Hildegard of Bingen: A Book of Essays. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1998, p. 61.

[v] Donald Campbell. Arabian Medicine and its Influence on the Middle Ages. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., 1926, p. 114.

[vi] Rowland, op. cit., p. xv.

[vii] Gillian Clark. Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Life-styles. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993, p. 67.

[viii] James Joseph Walsh. Medieval Medicine. London: A & C Black, 1920, p. 166.

[ix] Thomas G. Benedek. The Roles of Medieval Women in the Healing Arts, in Douglas Radcliff-Umstead, ed. The Roles and Images of Women in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Publications on the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Vol. III, 1975, p. 149.

[x] Campbell, op. cit., pp. 124-125.

[xi] Walsh, op. cit., p. 8.

[xii] Eugene Mason, trans. The Lays of Marie de France and Other French Legends. Everyman’s Library. New York: Dutton, 1911, reprinted 1964, ll. 103-108 (my translation).

[xiii] Benjamin F. Shearer and Barbara S. Shearer, eds. Notable Women in the Life Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996, pp. 145-146.

[xiv] George Sarton. Introduction to the History of Science. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1927, Vol. I, p. 283.

[xv] Walsh, op. cit., passim.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University.

August 18, 2012

Alhazen: The First True Scientist?

by Pamela Toler

Islamic scholar Abu Ali al-Hassan Ibn al-Haytham (ca. 965-1041), known in the West as Alhazen, began his career as just another Islamic polymath. He soon got himself in trouble with the ruler of Cairo by boasting that he could regulate the flow of the Nile with a series of dams and dikes. At first glance, it had looked like such a simple problem. But the more he studied it, the more impossible it seemed. Al-Hakim, known to his subjects as the Mad Caliph with good reason, was getting impatient. Alhazen only saw one way out: he pretended to be crazy. Safely confined as a madman until the caliph’s death ten years later, Alhazen continued to work.

Time and isolation? It was the perfect situation for a man with a book to write.

While confined in his home, Alhazen revolutionized the study of optics and laid the foundation for the scientific method. (Move over, Sir Isaac Newton.) Before Alhazen, vision and light were questions of philosophy. Alhazen considered vision and light in terms of mathematics, physics, physiology, and even psychology. In his Book of Optics, he discussed the nature of light and color. He accurately described the mechanism of sight and the anatomy of the eye. He was concerned with reflection and refraction. He experimented with mirrors and lenses. He discovered that rainbows are caused by refraction and calculated the height of earth’s atmosphere. In his spare time, he built the first camera obscura.

Modern physicist Jim al-Khalili, in his excellent The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance, calls Alhazen the greatest physicist of the medieval world, and possibly the greatest in the 2000 years between Archimedes and Sir Isaac Newton. His Book of Optics was first translated into Latin in the late twelfth or early thirteen century. It had an enormous impact on the work of western scientists from Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1292) to Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

August 16, 2012

What Color Is Your Habit?

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt (W&M Regular Contributor)

In the early fifteenth century male ecclesiastical visitors to the convent of Santa Clara in Barcelona cited the nuns for wearing an irregular and inappropriate habit. Rather than donning the traditional garb of Franciscan nuns, a gray or brown habit, the nuns wore a black habit more like that of the Benedictine Order. The visitors objected, but the nuns resisted and stuck to their sartorial guns. Stubborness prevailed on both sides of the debate and the contest over their habits dragged on for about a century and was ultimately appealed to Rome. Why were both sides so persistent? How did a question of clothing reach all the way to the papcy? Considering that the nuns were rarely, if ever, seen by others, why did it matter what they wore?

I have written previously here about the ways in which premodern clothing made statements about class and identity. It was not different for the nuns. Despite the fact that one modern historian has trivialized the decision of the Santa Clara nuns, claiming that the nuns simply wanted to exchange a drab habit for a more prestigious one*, it is clear that there was much at stake for these Franciscan women.

In fact, although Franciscan, the convent had a history of wearing the Benedictine habit. The nuns traced unbroken lineage to what they called the habit of San Damiano. This was a reference to the first religious community personally founded by Saint Clare in the early-thirteenth century. Because there was a ban on new religious orders when the community was formed in 1219, Cardinal Hugolino had placed the women under the Benedictine Rule. For the nuns of Santa Clara of Barcelona wearing the Benedictine habit let them claim an institutional identity built on a centuries-old connection between themselves and their sainted foundress. The nuns resisted the attempts to make them wear the Franciscan habit, and ultimately transferred the convent to the Benedictine Order. The local Franciscan hierarchy objected vigorously and appealed the decision to Rome. But the papacy upheld the nuns’ choice.

Another dispute over habits rooted in questions of identity erupted at the convent of Le Vergini in Venice. Here, in the early sixteenth century, the Augustinian nuns fought over a different choice of colors. A group of nuns was sent to reform the community and they wore grey habits. The original members wore white. After some discussion the two groups reached an agreement that they would all wear white. Trouble ensued, however, when the lay sisters (women who didn’t take solemn vows and frequently performed more menial tasks around the convent) adopted this color for their habits. Their decision violated a long-standing tradition of distinguishing between the habits worn by choir nuns and habits worn by lay sisters—a kind of hierarchy within the convent. The solemnly professed nuns wanted to be certain that the color of their habits signified their status as distinct.[1]

Habits, then, though hardly ever seen by outsiders, embodied important issues. Despite the monastic lifestyle’s insistence upon washing away attachments to material culture, habits mattered immensely to the women who wore them. Woven through their colors were questions of identity, tradition, and hierarchy.

* Interestingly, because of the dyes needed to prepare it, black was an expensive color to produce in the late Middle Ages, which may have made black habits a more prestigious item.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Chair and Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She writes on the history of gender in premodern Europe.

[1] For more on this story, see Kate Lowe’s, Nuns’ Chronicles and Convent Culture in Renaissance and Counter-Reformation Italy (New York, 2003).

August 15, 2012

Stagecoach Madness

“I can remember no night of horror equal to my first night’s travel on the Overland Route,” wrote a stagecoach traveler in the 1860s. This poor man had to resort to wearing a donut-shaped air cushion around his neck to stop his skull cracking against the sides of a violently swaying coach.

“I can remember no night of horror equal to my first night’s travel on the Overland Route,” wrote a stagecoach traveler in the 1860s. This poor man had to resort to wearing a donut-shaped air cushion around his neck to stop his skull cracking against the sides of a violently swaying coach.

Another long-distance commuter wrote this, “I am here, and without any broken bones, but how my bones happen to be whole after the fearful ride up and down the Sierra Nevada mountains, I haven’t the remotest idea.” Reporter A.J. Marsh spent a good part of his trip on the outside of the stage, beside the driver. It was night and the coach was tearing along a winding road with the wheel sometimes no more than six inches from precipitous drops. Glancing nervously at the driver, Marsh was horrified to see him fast asleep. When shaken awake, the driver grumpily protested that he always slept at this point in the journey as the “horses knew every foot of the way.”

Theatrical agent Edward Hingston got a shock when travelling on the same route during the day. He glanced out the open window (no glass, lest shards cut passengers) and spotted fragments of a coach scattered at the bottom of a ravine a quarter of a mile deep. He asked the driver if anybody had died in the terrible accident. Two, replied the driver, and three severely injured survivors had recovered enough to sue the stage company. That won’t happen again, he drawled. “If we had an accident and you were badly hurt I should have to knock you on the head. Dead men don’t bring actions.”

Sir Richard Burton (the explorer, not the movie star) bluffly described his coach rolling over twice on the flatter and sandier road from Dayton to Carson City in 1861. Two of his party cracked their heads but he was more upset about a cracked bottle of cognac. “Eheu!” he lamented in mock solemn Latin “Hic jacet ampora vini.” (Alas! Here lies my bottle of wine.)

It must have been hell to ride on a stagecoach. Notices issued by stagecoach companies give a hint at what you might expect: Spit on the leeward side… Don’t smoke a strong pipe inside the coach… Never shoot on the road as the noise might frighten the horses… Don’t point out where murders have been committed, especially if there are women passengers… Don’t growl at the food received at the station… When the driver asks you to get off and walk, do so without grumbling, he won’t request it unless absolutely necessary… If the team runs away – sit still and take your chances. If you jump, nine out of ten times you will get hurt… The best seat inside a stage is at the front facing back, even if you have a tendency to sea-sickness when riding backwards.

“It is a fearful thing to be at sea in a stagecoach,” agreed Mark Twain.

And I haven’t even mentioned the very real possibility of being tortured to death by Indians or shot by highwaymen.

So did anybody ever have a pleasant journey on a stagecoach?

There is one famous account by a certain Sam Clemens. He writes of a stagecoach journey he and his brother took across country in 1861. Their well-suspended Concord coach was so loaded with mail that they were the only passengers. This allowed them the freedom to ride in their underwear, which Sam called “undress uniform”. Sometimes they stretched out on the mail sacks. Othertimes they clambered up onto the roof of the coach and sat with their backs against luggage and their legs dangling over the side. From here they could watch the world spin by as they ate a cold lunch of ham and hard-boiled eggs. Smoking their post-prandial pipes, they admired the scenery of the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains and Great Alkali Deserts dotted with buffalo, coyotes, jackass rabbits, desperados, Indians and Pony Express riders.

There is one famous account by a certain Sam Clemens. He writes of a stagecoach journey he and his brother took across country in 1861. Their well-suspended Concord coach was so loaded with mail that they were the only passengers. This allowed them the freedom to ride in their underwear, which Sam called “undress uniform”. Sometimes they stretched out on the mail sacks. Othertimes they clambered up onto the roof of the coach and sat with their backs against luggage and their legs dangling over the side. From here they could watch the world spin by as they ate a cold lunch of ham and hard-boiled eggs. Smoking their post-prandial pipes, they admired the scenery of the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains and Great Alkali Deserts dotted with buffalo, coyotes, jackass rabbits, desperados, Indians and Pony Express riders.

“Nothing helps scenery like ham and eggs,” wrote Sam 10 years later. “Ham and eggs, and after these a pipe – an old, rank, delicious pipe – ham and eggs and scenery, a ‘down grade,’ a flying coach, a fragrant pipe and a contented heart – these make happiness. It is what all the ages have struggled for.”

But of course Sam Clemens was Mark Twain, so you can’t believe a thing he says.

Caroline Lawrence is the author of a passel of history-mystery books for kids. Her new Western Mysteries series is set in Nevada Territory during the era of the Silver Boom. The Case of the Deadly Desperados is out now.

August 9, 2012

Diana, Callisto and Philip II

Between 1553 and 1562, Titian painted a number of mythological scenes for Philip II. Among these was a painting of Diana and Callisto. In the story, told most famously by the Roman poet Ovid, Callisto is one of the unmarried girls forming the virgin goddess’s entourage. Jupiter catches sight of her, and disguises himself as Diana so she won’t be alarmed (this in itself is a very interesting comment on how the entourage works – Callisto is not remotely alarmed when the fake ‘Diana’ kisses her). He then rapes her and makes her pregnant. Callisto manages to cover up her pregnancy for 9 months, but then Diana suggests all the girls go skinny-dipping. Callisto tries to keep her clothes on, but the other girls strip her to reveal her advanced pregnancy. Diana bans her from the group. When Callisto gives birth, Jupiter’s wife Juno – jealous at Jupiter’s infidelities – turns her into a bear. 15 years later, Callisto spots her human son out hunting and approaches him. He, of course, sees this as a bear coming towards him and is about to kill her when Jupiter takes her up into the heavens and makes her into a constellation – the Great Bear.

Titian’s painting shows Callisto’s tear-stained face in shadow, her contorted body contrasted with Diana’s queenly pose. The way the other girls are holding her body down recalls the start of her pregnancy in an act of rape. The painting can now be seen with the two paintings of Diana and Actaeon in London at the National Gallery’s current exhibition, ‘Metamorphosis: Titian 2012′, in which modern artists respond to Titian.

The National Gallery asked me to talk about this painting for an exhibition podcast (Podcast 70, August 2012 – also featuring the late Ted Hughes!) because I’ve worked on the goddess Artemis/Diana. Standing by the painting for the best part of an hour, I found myself thinking about the medical ideas behind it. In the 1550s, ideas about women’s bodies were very much rooted in ancient Greek medicine. Sixteenth-century medical writers were interested in questions which, to us, seem rather odd: did Amazons menstruate? could a girl become pregnant before she had had a menstrual period?

One ancient theory was that menstrual blood was produced from normal food and drink, building up in the body over the month, and acting as the raw material out of which a baby would be made. So it was theoretically possible to have accumulated enough blood in just the first month of a girl’s ‘ripeness’ for her to make a baby, if the male seed happened to enter at that point. To us, Diana’s treatment of Callisto seems most unfair – it wasn’t her fault that a god raped her. But perhaps there is something more going on here – perhaps she should have opted out of Diana’s entourage because her body was actually mature enough to contribute to making a baby.

It’s also important to think about what this painting meant to Philip II, who seems to have liked these images not just as ways to show off his knowledge of ancient myths, but also for the opportunities they gave to look at naked women. In particular, there’s a girl behind the abject Callisto who has one breast exposed. And Callisto’s clutching hand is so close to it that to a male viewer at Philip’s court it would have suggested his own hand on that breast. It’s interesting here that in the companion painting of Actaeon seeing Diana taking a bath, Titian seems to show him revealed as peeking at her from behind a curtain, rather than coming upon her completely by accident, as the ancient myth would suggest. For Philip, these were images of a goddess punishing mortals simply because she can: they therefore had something to say about his own kingly power. But the images also said something about the secrets of the female body and male curiosity concerning what was really going on in there. Apparently, Philip kept curtains over these paintings when his wife was around…!

August 6, 2012

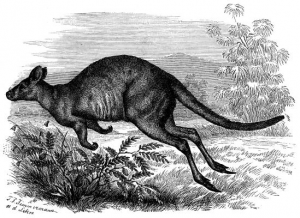

The Kangaroo’s Tale: How an errant elevator door ended an odd form of popular entertainment

When an elevator door slammed shut at the Minneapolis Auditorium on March 20, 1940, an era of American entertainment came to a bloody end. The door crushed the six-foot-long tail of Peter the Great, a famed boxing kangaroo, who was touring the U.S. and had just demonstrated his skills to a Minneapolis audience.

Peter’s owners and managers, Mr. and Mrs. Ted Elder, considered the injury minor and wrapped the marsupial’s tail with a bandage. They began driving Peter to his next engagement in Omaha, but it became obvious along the way that the kangaroo was in distress. The Elders rushed Peter back to the O.B. Morgan Dog and Cat Hospital in Minneapolis, and they were about to have the damaged body part amputated when the 160-pound kangaroo died.

Peter, a singularly famous boxing kangaroo, had made a notable impression on American popular culture. Less than a year before, he fought a boxing match with “Two Ton” Tony Galento, a pugilist who had once floored Joe Louis. During an exchange of blows, Peter dropped back on his tail and kicked Galento in the groin. The man-versus-beast match ended in a draw. A wave of publicity carried Peter to shows around the country.

If Peter had lived, he would have played a role in U.S. electoral politics. He was scheduled to appear with comedienne Gracie Allen and serve as the mascot for her 1940 mock run for the Presidency. Without Peter’s help, Allen’s Surprise Party never found traction, and Franklin Roosevelt won the 1940 election without a satirical opponent.

In a lawsuit they filed against the city of Minneapolis, the Elders claimed that Peter’s boxing and entertainment talents resulted from his special training. “Peter the Great,” Mrs. Elder testified, “was no ordinary kangaroo.” The city countered that swinging and kicking when threatened is instinctive behavior for his species. A jury sided with the city, and Peter’s owners did not receive the $75,000 they sought in compensation for their loss.

No other kangaroo rose to Peter’s level of fame after his death. As exploitations of stage animals began to smell of cruelty, boxing kangaroos disappeared except as cartoonish symbols of Australian resilience. Today we never encounter them in the flesh. Peter the Great’s fame and profession belong to the past.

Sources:

“Jury Refuses Damages for Death of Kangaroo.” Milwaukee Journal, October 8, 1940.

“Peter, Boxing Kangaroo, Dies.” The New York Times, March 24, 1940.

Zahn, Thomas R. The Minneapolis Auditorium and Convention Center: The History. 1987.