Holly Tucker's Blog, page 77

September 27, 2012

The Mistress of Mourning

By Karen Harper

I have researched Tudor culture for years while writing my novels set in that era, but when I prepared to write MISTRESS OF MOURNING (titled THE QUEEN’S CONFIDANTE in the UK,) I realized I knew little about embalming practices, at least those for the noble and royal. When I learned my chandler heroine would not only make and sell candles but deal in waxen shrouds (cerements,) I found her occupation doubly intriguing.

I have researched Tudor culture for years while writing my novels set in that era, but when I prepared to write MISTRESS OF MOURNING (titled THE QUEEN’S CONFIDANTE in the UK,) I realized I knew little about embalming practices, at least those for the noble and royal. When I learned my chandler heroine would not only make and sell candles but deal in waxen shrouds (cerements,) I found her occupation doubly intriguing.

Votive candles for the dead were a huge business. Many funeral candles for the rich, a few for the poor. But chandlers also made shrouds from Holland cloth permeated with wax, which were carefully rolled to prevent cracking. Corpses of the rich and noble were wrapped in these after a procedure in which organs were removed by either physicians, barber surgeons (there was much strife between these two groups) or yes, chandlers.

Then, of course, there were very talented chandlers/wax carvers who produced the “masks” for effigies of the rich and famous. Royals like Queen Elizabeth I had death masks made to go with their effigies which lay atop their coffins for their public funeral processions through the streets. When Henry VIII died, surgeons to remove the organs, apothecaries with sweet herbs to fill the empty body cavities, and wax chandlers were summoned to the palace.

The idea of portrait waxes and wax shrouds goes back to the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. Wax was an easy medium to use with hands and simple tools, and, of course, wax greatly emulates skin. In my novel, which begins in 1501, it is my merchant-class heroine’s talent for wax carving that brings about her summons to the palace, for the

wife of King Henry VII wants effigies of her dead children—and help solving a double murder.

Karen Harper is the New York Times bestselling author of historical novels and contemporary suspense. Her current historical novel is MISTRESS OF MOURNING from NAL. Please visit her website at www.KarenHarperAuthor.com

September 24, 2012

The Greatest Wonder Which the World Can Show

By P.D. Smith

While writing City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age, two ideas were at the forefront of my mind. First I wanted to celebrate one of humankind’s greatest achievements. Cities are remarkable technological and architectural creations. It’s easy to forget this, especially if you have spent your life in cities. I wanted the book to convey something of the awe that Heinrich Heine experienced on arriving in what was, in 1827, the greatest city on earth:

While writing City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age, two ideas were at the forefront of my mind. First I wanted to celebrate one of humankind’s greatest achievements. Cities are remarkable technological and architectural creations. It’s easy to forget this, especially if you have spent your life in cities. I wanted the book to convey something of the awe that Heinrich Heine experienced on arriving in what was, in 1827, the greatest city on earth:

‘I have seen the greatest wonder which the world can show to the astonished spirit; I have seen it, and am more astonished than ever – and still there remains fixed in my memory that stone forest of houses, and amid them the rushing stream of faces, of living human faces, with all their motley passions, all their terrible impulses of love, of hunger, and of hate – I am speaking of London.’

Second, I wanted to highlight the importance of history. For all their amazing infrastructure, cities are human environments. As you walk through a city, you become aware of the traces of countless past lives. The proto-Situationist Ivan Chtcheglov has expressed this rather beautifully: ‘All cities are geological and three steps cannot be taken without encountering ghosts’. From the faded remains of old advertisements painted on walls (ghost signs) to the echoes of age-old dreams of a shining city on a hill in street plans and architecture, cities are rich storehouses of human history.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in the twelfth-century basilica of San Clemente in Rome. If you go down into the crypt, you can walk along the nave of a church built before AD 385. But venture deeper still and there is a nearly two-thousand-year-old temple to Mithras. In the chill gloom of this subterranean space, the ghosts of the city become an almost tangible presence.

By the end of the nineteenth century, London was the largest city the world had yet seen – a sprawling, smoky metropolis of more than six million people. Britain was the first country in which more than half of the population lived in cities. But it was not until the beginning of the twenty-first century that the world as a whole crossed this threshold. Now the largest city is Tokyo, a megacity of some 36 million people, slightly more than live in Canada. In the coming decades, Mumbai will probably exceed even this once unimaginable scale.

The world is entering an unprecedented urban age. Cities will face huge problems, such as megaslums, climate change, and dwindling fresh water supplies. But cities have had to deal with slums and with environmental crises before. The earliest cities in Mesopotamia also had to contend with a changing climate. Unfortunately, their attempts to deal with it through irrigation schemes ultimately proved fatal – a clear warning to us from the past.

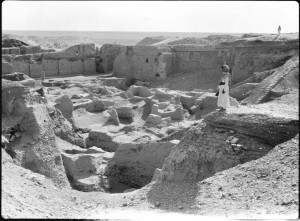

The fate of these first cities is a reminder that, in time, even the greatest cities return to the dust from which they emerged: Ur, Babylon, Mohenjo-daro, Tenochtitlán and others. When we walk through today’s streets, beneath our feet lie yesterday’s cities and I hope my book shows how much we can learn from our urban past.

P. D. Smith is the author of four books, including Doomsday Men: The Real Dr Strangelove and the Dream of the Superweapon. He is an Honorary Research Associate in the Science and Technology Studies Department at University College London. His website is www.peterdsmith.com.

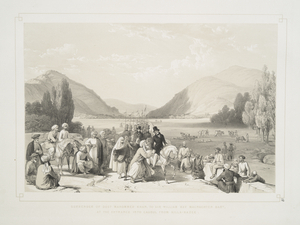

Image: Ur, view of the ruins, 1932. Library of Congress, Call Number: LC-M33- 4697 [P&P].

Los Angeles Chinese Massacre, 1871

By Scott Zesch

The word “massacre” usually brings to mind lonely American landscapes such as Wounded Knee, Mountain Meadows and Sand Creek—not a busy metropolis like Los Angeles. Yet that city’s first race riot, dating back all the way to 1871 and largely forgotten today, came to be known as the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre.

At the time it occurred, Los Angeles was a Wild West town of only 6,000 residents. Most people outside of California had never heard of it. Californians knew about the place mainly because it had the state’s highest per capita murder rate and largest number of lynchings.

Shortly before sundown on October 24, 1871, a gunfight broke out between members of rival Chinese factions. Angelenos ran to Chinatown to see what was happening. A reckless white rancher discharged his revolver into a Chinese store and was killed by return fire. Within a short time, an angry crowd of about 500 Anglos and Latinos gathered in the streets of Chinatown, surrounding the low adobe buildings. As darkness fell, the Chinese were trapped inside their homes and shops. After a three-hour standoff, the mob broke into the Chinese headquarters, seized random victims, and dragged them off to be hanged. Eighteen Chinese men were murdered that night.

This half-hour killing spree was the bloodiest attack on Chinese immigrants the country had experienced at that time. The Chinese Massacre was also the first event to draw nationwide attention to Los Angeles. It was a public relations disaster for the small but growing town, whose civic leaders were careful not to mention the atrocity in a local history they published five years later. Today, a small plaque near the Hollywood Freeway is all that commemorates the city’s first deadly racial uprising and one of America’s worst hate crimes.

Scott Zesch is the author of The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 (Oxford University Press). His previous book, The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier, won the TCU Texas Book Award.

September 23, 2012

The Strange Journey of Napoleon’s Penis

By Karen Abbott (W&M Contributor)

In 1821, the year of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death from stomach cancer, his penis embarked on a journey that rivaled its owner’s bloodthirsty trek across Europe. It began on an autopsy table on the British island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, which had been the emperor’s home since the ill-fated Battle of Waterloo. In the presence of seventeen men, including various British and French officials, Dr. Francesco Antommarchi removed Napoleon’s liver and stomach and dropped them in jars of ethyl alcohol. It was to the emperor’s detriment that the doctor held a grudge against him; Napoleon had never liked Antommarchi and pointedly left him out of his will.

Shortly after the autopsy, rumors circulated in Paris that the doctor’s aides had smuggled various souvenirs from the island: strips of the bloody bed sheet, teeth, nail clippings, splinters of rib, locks of hair, chunks of bowels. Dr. Antommarchi himself filched the emperor’s death mask and two pieces of lower intestine, which he left with friends in London. Napoleon’s chaplain, Abbé Ange Vignali, laid claim to the most intimate part of the royal anatomy, boasting about his treasure when he went home to Corsica. Two decades later, when the British government allowed Napoleon’s body to be returned to Paris, Vignali’s relatives kept Napoleon’s penis for themselves—at least until 1916, when descendants put the Vignali collection up for auction. The organ was described thusly in the catalogue: “a mummified tendon taken from [Napoleon’s] body during post-mortem.”

An unknown British collector purchased the penis, which had been exposed to the air over the previous century and shrunk considerably. In 1924, eccentric American collector A.S.W. Rosenbach bought it for £400. Home in Philadelphia, he boasted of the relic, used it as a conversation piece for parties, and temporarily loaned it to the Museum of French Art in New York, which displayed it on a small velvet cushion. “Maudlin sympathizers sniffed; shallow women giggled, pointed,” Time magazine reported. “In a glass case they saw something looking like a maltreated strip of buckskin shoelace or a shriveled eel”—a verdict that would give anyone a complex.

In 1969, the Vignali Collection was shipped back to London for auction, but Napoleon’s penis failed to sell. Eight years later, the collection was broken up and auctioned in Paris, where Columbia University professor Dr. John K. Lattimer—America’s leading urologist—bought it for 13,000 francs, about $2900. He had it X-rayed at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, which confirmed that it is definitely a penis (although French cultural officials remain skeptical of its provenance, and refuse to exhume Napoleon’s body for examination). Lattimer kept his Napoleonic trophy in a suitcase under his bed in Englewood, New Jersey, where it stayed until he died in 2007. His daughter has fielded at least one $100,000 offer and has so far showed it to only one person, author Tony Perrottet, who deemed it “certainly small, shrunken to the size of a baby’s finger, with white shriveled skin and desiccated beige flesh.” Josephine, eat your heart out.

Karen Abbott is the New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City and American Rose. Her next book, a true story of four female Civil War spies, will be published by HarperCollins in 2014.

Sources: Tony Perrottet, Napoleon’s Privates: 2,500 Years of History Unzipped. New York: Harper Entertainment, 2008; Christopher Shay, “Napoleon’s Penis.” Time Magazine, May 10, 2011; Graeme Donald, Loose Cannons: 101 Myths, Mishaps, and Misadventures of Military History. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2009.

September 22, 2012

The First Robot

By Sidney Perkowitz (Atlanta Science Tavern contributor)

Robot as clanking machine. Elektro and his dog Sparko, made by the Westinghouse Corporation, as they appeared at the 1939 New York World’s Fair (Senator John Heinz History Center).

Among cutting-edge technologies, robotics ranks high when you think of all it entails – or at least, all it would entail to make robots as seen in fiction. A robot like those Isaac Asimov made famous is typically a somewhat humanoid metal machine that walks, talks, sees, hears, and understands, and acts autonomously. If in addition it looks almost perfectly human, it becomes an android like Commander Data in Star Trek or David in the film Prometheus (2012). Making these would require advanced technology we have yet to develop. But artificial beings date back to Talos in Greek myth, a bronze creature that guarded the island of Crete, and to the Golem, a creature made of clay that protected the Jews of Prague in medieval times, among others.

These are not robots, however. Robots were born later, on January 25, 1921 and as it happens, also in Prague, at the world premiere of Karel Čapek’s play R. U. R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots).

Čapek was a productive Czech writer with wide-ranging ideas. In R. U. R. he imagined a future in which humanity makes artificial creatures called “Robots” (always capitalized in the script and actually coined by Čapek’s brother Josef) after the Czech word “robota,” which means forced labor by a serf, or “robotnik,” meaning “worker.” Indeed, these synthetic beings are manufactured to carry out the drudgery that people do not want to. Unsurprisingly, they come to understand that they are being exploited and rise up with great violence, killing all humanity except for a single survivor.

Robot as artificial protoplasm, from the original stage production of R. U. R., Prague, 1921. (Image reproduced from the works of Prof. Jana Horáková, Masaryk University, Czech Republic, with her permission.)

These ideas, novel at the time, made the play a worldwide sensation then (by 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages) and have kept it alive since. It is constantly being revived; it inspired Gizmo, a contemporary play about robots by Anthony Clarvoe, first presented this year; and in title at least it has also inspired a film called R. U. R., due for release in 2014.

The original R. U. R. spoke both to its historical moment and universally. Čapek wrote the play in the era of the Russian Revolution of 1917 – 1918, in part a worker’s uprising. The revolution replaced old tsarist Russia with the Soviet Union, which in its rhetoric was devoted to forming a just and classless society that gave workers their due. But the Soviet Union rapidly became a totalitarian state that dehumanized its citizens. Whether deliberately or not, the plot and events in R. U. R. reflect much of what was going on at the time.

The play also presents broader themes because, despite the robots, it is not about technology but about people and technology. As Čapek wrote in 1923, “For myself, I confess that as the author I was much more interested in men than in Robots.” One theme is the fear of machines replacing people, still an issue today. Another is a moral one: what are humanity’s responsibilities toward sentient beings it might create? The humans in R. U. R. either treat the robots like unfeeling machines, or uplift them by making them more nearly human. Neither works well, leading to the play’s robot revolution and illustrating that this is a hard question that we might have to answer sooner than we think.

In a way, R. U. R. also foretold the biological engineering that is now taking halting steps toward creating artificial life. The robots in the play are not clanking metal constructions, but made of a substance “which behaved exactly like living matter” – synthetic protoplasm processed to make robots complete with brains, livers, nerves and veins. The results look human, not machine-like, and that’s where the power of R. U. R. lies: it makes us see ourselves in our robots, and our robots in ourselves.

Sidney Perkowitz is Candler Professor of Physics Emeritus at Emory University. His varied popular science writing includes the book Digital People , articles, and blogs about robots, most recently with this post at the Science and Entertainment Exchange. You can find out more about Sidney’s work and contact him at his website.

September 20, 2012

Dialog in Historical Fiction

Last month, I presented a session on “The Ten Commandments of Writing Historical Fiction” at the Summer Conference of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. (Many thanks to the readers of this blog who gave me suggestions for a tenth commandment—“nine commandments” doesn’t have the right ring to it!) The session was very well received, and I got great questions and comments.

Then someone asked how to make dialog sound authentic.

I never know what to say to this, because truly, there are as many answers as there are historical novels—or at least as many as there are historical novelists. For archaic language, there’s Howard Pyle’s classic Otto of the Silver Hand:

“Potstausand!” he cried; “art thou gone out of thy head to let thy wits run upon such things as this of which thou talkest to me?”

(Please note that this example of speaking forsoothly comes from lips of a swineherd.)

I loved that book as a child. I still remember episodes, scenes, characters, even though I last read it more than forty years ago. But that kind of dialog would seem old-fashioned and silly today.

Or an author could go to the other extreme and use contemporary idiom, as Barry Unsworth did in Songs of the Kings:

“They must have known he had a screw loose”

“That’s the sort of thing that is bound to look impressive on a person’s CV”

“[I]f he thinks you can fight a war without collateral damage, he’s totally mistaken”

This works for me, but I think you have to be as brilliant a writer as Unsworth to carry it off, and even then it will bother a lot of readers (take a look at the Amazon reviews!).

An author might choose the middle ground that worked for T. H. White in The Once and Future King, where the majority of speech is in a modern-sounding idiom but without Unsworth’s deliberate neologisms, except when Merlyn travels to the present. White uses archaic language only occasionally, in scenes of great emotion or portent, sometimes quoting Mallory directly.

“[Arthur] spoke in the old-fashioned talk, and said with a full voice: ‘Sir, grant mercy of your great travail that ye have had this day for me and for my Queen.’ Guenever, behind his smiling loving face, was sobbing as if her heart would burst.”

and:

“‘Oh, well,” said Kay, ‘I bet the old man caught it for him.’

“‘Kay,’ said Merlyn, suddenly terrible, ‘thou wast ever a proud and ill-tongued speaker, and a misfortunate one. Thy sorrow will come from thine own mouth.’”

So I don’t know what to say when asked that question except to fall back on reader expectations, personal style, and voice. If you want your dialog—or any other part of the text—to recall in its vocabulary, rhythm, syntax, and grammar the time where your story is set, the best I can suggest is immersing yourself in the speech patterns of the era (when possible—I wasn’t about to pattern my characters’ speech in King of Ithaka on Iron-Age Greek, much less on Linear B in Dark of the Moon!). I had fun coming up with phrases to avoid anachronisms, though. In Dark of the Moon, I couldn’t say someone was as curious as a cat because cats hadn’t come to Greece yet. So I said she was as curious as a mouse. Instead of “the straw that broke the camel’s back” in King of Ithaka, I said “the fish that broke the pelican’s beak.”

I’d love your examples of dialog in historical fiction—both good and bad. Forsooth.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University. Visit her website and her blog.

September 18, 2012

Déjà vu All Over Again? Attack on the British Garrison in Kabul, 1841

by Pamela Toler

James Atkinson. The Surrender of Dost Mahommed Khan. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

The story I’m about to tell is confusing. It’s about people you’ve never heard of, some of whom make bad decisions. In the end, people die and nothing much changes. In short, it’s a story about the West and Afghanistan.

In 1838, Dost Muhammad Khan was the Amir of Afghanistan. He had seized the throne in 1824 from Shah Mahmud, who had previously deposed his own brother, Shah Shuja. (Don’t feel sorry for Shah Shuja. He gained the throne in 1803 through a series of conspiracies that dethroned two of his brothers.) Despite the fact that he seized a throne that wasn’t his, Dost Muhammad was a popular and capable ruler who restored peace and prosperity.

In 1837, a Persian army laid siege to the Afghani city of Herat. Unable to come to terms with the British for military aid, Dost Muhammad turned to the Russians for support.

The governor-general of British India, Lord Auckland, assumed that Afghan friendship with Russia meant Afghan hostility to British India. * Based on reports from Sir William Macnaghton, the British envoy in Kabul, Auckland decided the only way to save Afghanistan from Persian and Russian aggression was to restore the elderly Shah Shuja to the throne he had lost thirty years before.

On October 1, 1838, Auckland issued the Simla Manifesto, declaring Britain’s intention of restoring the rightful king of Afghanistan to his throne. Shah Shuja would enter Afghanistan at the head of his own troops, with a little support from the British army. Once he was securely in power, the British army would withdraw.

The British had been led to expect that Shah Shuja would be welcomed back on the throne with no more effort than the threat of British bayonets. Instead the Army of the Indus had to fight its way to Kabul through country that its commander, General John Keane, described as “full of robbers, plunderers and murders, brought up to it from their youth.” It took them eight months to reach Kabul and install Shah Shuja on the throne.

It quickly became clear that the only way the new Amir would stay on the throne was if the British army kept him there. The Army of the Indus became an inadequate and unwelcome army of occupation. Afghanistan was in a permanent state of unrest, with random acts of hostility and violence directed against its British occupiers.

The British leadership of the expedition was ineffectual. General Elphinstone, the commander in chief, was an elderly invalid who was no longer able to direct an army in the field and unwilling to delegate authority to his deputy. The real authority over the expedition lay with the viceroy’s envoy, Macnaghten. Under the direction of Macnaghten and Elphinstone, the British moved out of the Balla Hissar, a fortified palace outside of Kabul, and built a conventional cantonment, including a racecourse, and settled into garrison life as if they were safely in India. They even called for their families to join them.

Despite unmistakable signs of trouble, the British were completely unprepared when open revolt broke out in 1841. On November 2, an Afghan mob stormed the house of a senior British political officer who was said to have trifled with local women and murdered him and his staff. The British soon found themselves besieged in their indefensible cantonments. Efforts to clear the high ground that dominated the cantonments failed. An attempt at parley resulted in the murder of Macnaghten.

The British made the reluctant decision to retreat to India. They made a treaty with the Afghans, who guaranteed their safe conduct to India in exchange for British withdrawal from Kandahar and Jalalabad. A number of British officers and their families were held as hostages, a demand that ultimately saved their lives. On January 6, 1842, 4500 British and Indian soldiers and 12,000 wives, children and servants marched out of Kabul. On January 13, a single survivor, Doctor William Brydon, reached the British garrison at Jalalabad, sixty miles to the east. The rest were slaughtered by the Ghilzai tribesmen who controlled the mountain passes.

Shah Shuja was assassinated four months later. Dost Muhammad returned to Afghanistan the following year and ruled until his death in 1863.

* For much of the nineteenth century the British were afraid that Russia would invade India through Afghanistan. The result was the nineteenth century version of the Cold War that Rudyard Kipling dubbed “the Great Game” in Kim.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change. Her most recent book is Mankind:The Story of All of Us–a companion to an up-coming History Channel series.

September 14, 2012

Love Potion Number IX

In the steamy hot room of the Roman baths, a muscular gladiator sighs as a slave scrapes the sweat, oil and dirt from his skin. The slave uses a strigil, a curved metal tool that performs the same task as the modern loofah. The strigil – or stlengis (στλεγγίς) as it’s called in Greek – has a cross-section like a thin piece of celery and curved like a sickle, but the edges are dull. You couldn’t cut yourself with it. But the strigil (right) is designed to collect the gluey mixture of sweat and oil called gloios (γλοίος) in Greek and strigmentum in Latin. Why? Because ‘gladiator sweat’ was worth a lot of money.

In the steamy hot room of the Roman baths, a muscular gladiator sighs as a slave scrapes the sweat, oil and dirt from his skin. The slave uses a strigil, a curved metal tool that performs the same task as the modern loofah. The strigil – or stlengis (στλεγγίς) as it’s called in Greek – has a cross-section like a thin piece of celery and curved like a sickle, but the edges are dull. You couldn’t cut yourself with it. But the strigil (right) is designed to collect the gluey mixture of sweat and oil called gloios (γλοίος) in Greek and strigmentum in Latin. Why? Because ‘gladiator sweat’ was worth a lot of money.

Pliny the Elder mentions small amounts of strigmentum changing hands for the equivalent of half a million dollars. Natural History 15.4.19

An inscription from Greece talks about revenue from the sale of gloios at a gymnasium. SEG 27.261

Roman doctors like Galen and Celsus note that it was good for inflammation of the nether parts of both sexes, and also for other aches and sprains.

If you go to Pompeii or almost any other Roman site, chances are the guides will delight in telling you that gladiator sweat was used as an aphrodisiac or love potion. In Pompeii a dozen years ago, a charming guide named Stefano told me that lovesick Roman women put gloios in the food of a man they wanted to seduce. I ate this up, as it were, and put this deliciously squirmy fact in my sixth Roman Mystery, The Twelve Tasks of Flavia Gemina, and have since tried to find evidence that I was accurate in so doing. I have as yet found no hard evidence.

A few years ago my hopes were raised when visiting some ‘Roman glassmakers‘ in Salisbury a few years ago, I saw a little blue bottle labelled for ‘gladiator scraping love potion’.

‘What’s your source?’ I asked excitedly.

‘You,’ they replied.

Recently I read an article about sweat by Naomi Wolf. The smell of the sweat of a sexually-aroused man, according to Wolf, can make a woman calmer, happier and even more fertile! So adding some sweat-smelling gloios to a mushroom casserole might indeed make the eater more receptive to one’s advances.

Recently I read an article about sweat by Naomi Wolf. The smell of the sweat of a sexually-aroused man, according to Wolf, can make a woman calmer, happier and even more fertile! So adding some sweat-smelling gloios to a mushroom casserole might indeed make the eater more receptive to one’s advances.

I still haven’t come across any concrete evidence of ‘gladiator sweat love potion’, but I am now more inclined to think that the charming Italian guides like Stefanos might just be right in saying gladiator sweat plus oil could have been the ancient equivalent of Love Potion Number IX. After all, they are Italian males, surely the world experts on love.

left: ornatrix at the Roman baths in Bath

Vocabulary:

γλοιός (Greek) = gloios = a gluey mixture of sweat, oil and dirt

strigmenta (Latin) = something scraped off, like gloios

στλεγγίς (Greek) = stlengis = a scraper to remove oil, sweat and dirt in the baths

strigil (Latin) = a scraper to remove oil, sweat and dirt in the baths

φίλτρον (Greek) = philtron = a love-potion, philter from the verb phileo – to love

venenum (Latin) = from Venus, originally love-potion, later drug, charm, poison, venom

Caroline Lawrence writes Roman Mysteries for kids aged 8 to 80. You can read more about her books at www.carolinelawrence.com

September 10, 2012

Seeds, wombs and ‘legitimate rape’

Image of the womb from the 16th c Jacopo da Carpi

By Helen King

Last month, in a much-repeated comment, Todd Akin recently claimed that ‘if it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down’. Not surprisingly, he has been ridiculed for the lack of knowledge of biology that this comment betrays. It didn’t take long, though, before history started to come into the discussion.

On 20 August the Guardian newspaper published an article on how the belief that a woman has to enjoy sex in order to conceive went back to medieval notions of the body. Some ancient authorities, used in medieval medicine, claimed that both men and women make ‘seed’ and both have to ejaculate it if conception is to take place. So, if the woman conceives, she must have ejaculated; and if she ejaculated, she must have had an orgasm; and if she had an orgasm, she must have enjoyed it. However, this was only one option in ancient and medieval medicine. Other authorities thought that only men made seed, so that women’s pleasure, or lack of it, was pretty irreleva And, as my fellow Classics professor Edith Hall pointed out in her blog, classical myth and drama flourished on stories where victims of rape became pregnant – Romulus and Remus would not have existed (insofar as mythical heroes ‘exist’) without the rape of their mother by a god!

But, actually, I don’t think that was quite what Akin was saying here. The idea that ‘the female body has ways’ reminds me of another ancient Greek idea, one found in one particular Hippocratic treatise called ‘On Fleshes’, namely that women can eject the male seed in the first few days of pregnancy.

The Hippocratic corpus is more like a library – it’s not one person’s work. Some texts included in it present women as supplying the raw material for a baby – blood – while men’s seed activates this and shapes it. They argue that a woman’s body could sometimes make a shapeless mass called a ‘mole’ (from the Greek word for ‘mill-stone’, implying something heavy and immobile). This would happen if she had a lot of blood, and the man’s seed was only ‘scanty and sickly’. If nothing moved after 3 months (the time taken for a male foetus to become active in the womb), or 4 (the time for a female foetus to start to move), ‘when this time has passed and there is no movement, it is obviously a mole’. They also thought that a woman knew when she had conceived because she would observe that the man’s seed had not fallen out, and she would actually feel the mouth of her womb closing up to keep the man’s seed inside her. Lying down with her legs crossed after sex would make it more likely that the seed stayed in.

The man who wrote ‘On Fleshes’ names his sources for the information he gives about how babies are made in the womb: the hetairai demosiai or public prostitutes. They know, he says, when they have conceived, and they destroy the child. There is nothing in the text to explain just how they do it. In cases where a married couple couldn’t conceive, ‘women have ways’ may have been a cultural move to say, it’s not men’s fault; their seed is up to the job, but those sneaky women know how to stop it working.

However, Akin’s remark separates ‘the female body’ from the conscious will of the woman. So another Hippocratic idea that strikes me as relevant is the ‘wandering womb’. Here too we find ‘the female body’ acting on its own. The womb moves from mechanical principles; if it gets too dry, it may start moving up towards the moisture of another organ, the liver. The Hippocratic authors may have been contemporary with Plato, who famously wrote in the Timaeus that both men and women have an ‘out-of-control’ organ – penis, or womb. Some contemporary debates about rape suggest that men can’t help it, if presented with an attractive woman. But ancient philosophy also proposed that the mind should be able to control the body. Perhaps the idea that ‘the female body has ways’ suggests that women are just too much ‘of the flesh’ to exert that control?

Jacopo da Carpi: a 16th century image of the womb

September 9, 2012

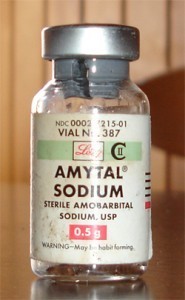

Was There Any Truth in Truth Serum?

by Jack El-Hai

Remember the routine from black and white espionage dramas of the 1940s and ‘50s? The bad guys detain a suspected spy, who won’t talk even after a rough interrogation. Soon, after receiving an injection of a colorless liquid, he’s muttering uncontrollably, spilling the details of an entire network of agents. The truth serum has done its job.

No drug has ever really worked this way. In 1916 Robert House, a Texas obstetrician, chanced upon the first pharmacological agent that appeared to put people in an unusual trance. He noticed that some of his patients who received the anesthetic scopolamine during delivery fell into a half-sleep in which they could sometimes answer questions without remembering having done so afterward. House grew convinced that their mental state under scopolamine’s influence was one in which it was impossible to lie — therefore, the drug could compel anyone to speak the truth.

No drug has ever really worked this way. In 1916 Robert House, a Texas obstetrician, chanced upon the first pharmacological agent that appeared to put people in an unusual trance. He noticed that some of his patients who received the anesthetic scopolamine during delivery fell into a half-sleep in which they could sometimes answer questions without remembering having done so afterward. House grew convinced that their mental state under scopolamine’s influence was one in which it was impossible to lie — therefore, the drug could compel anyone to speak the truth.

Like alcohol, scopolamine and the truth serum substitutes that would soon follow it depressed the central nervous system and diminished inhibitions. There was no greater guarantee of reliable truthfulness in House’s patients than in any soused person.

Undeterred by his lack of knowledge of psychology, pharmacology, or criminology, House spent the 1920s touring America’s jailhouses and police departments in demonstrations of administering scopolamine in the questioning of criminal suspects. He believed the drug would prove useful in the justice system not as a tool to make tight-lipped crooks talk, but as part of an interrogation technique that would give police investigators no excuse to use violence to extract confessions.

After House’s death in 1929, the use of scopolamine and later truth serums — sodium amytal and sodium pentothal — changed course. In an era of rising organized crime, the police wanted confessions. But the drugs made people suggestible and prone to giving fanciful and wrong answers. Over the years, some interrogators who continued using these drugs, despite numerous cases of false confession, crossed a line into abuse of suspects and miscarriage of justice. “The criminal who is likely to confess under sodium amytal is likely to confess anyway if skillfully interrogated,” the psychiatrist John M. MacDonald concluded in 1955. “The criminal who is able to withstand skillful interrogation is usually able to withstand examination while under the influence of drugs. The temptation to request a truth serum test as a short cut to the solution of a crime should be avoided.”

In its Townsend v. Sain decision of 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that confessions obtained using a truth serum were inadmissible. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, some law-enforcers called for a return to truth-serum interrogation. So far, nobody has publicly announced the development of a drug formulation proven to work.

Sources:

MacDonald, John M. “Truth Serum.” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, Vol. 46, 1955-1956, pp. 259-263.

Winter, Alison. “The Making of ‘Truth Serum.’” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 79, No. 3, Fall 2005, pp. 500-533.