Holly Tucker's Blog, page 76

October 20, 2012

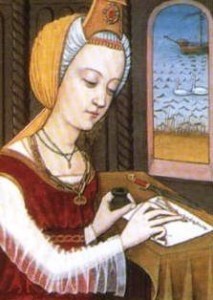

Two Medieval Women Physicians

Most people think of medieval women healers—if they think of them at all—as herb-women, maybe midwives, basically uneducated even by the standards of their time. But as I reported earlier, there’s evidence that a few women in the Middle Ages managed to get the same kind of training as their male counterparts. Some were even well enough respected that they were consulted, either in person or through their writings, by other physicians.

The best-known medieval medical text supposedly by a woman is the thirteenth-century manual of obstetrics and gynecology (and cosmetics!) known by the name of its author, Trotula. How much education Trotula had is unknown, although she presents herself as a physician, implying university training.

The best-known medieval medical text supposedly by a woman is the thirteenth-century manual of obstetrics and gynecology (and cosmetics!) known by the name of its author, Trotula. How much education Trotula had is unknown, although she presents herself as a physician, implying university training.

Trotula says she wrote her book “to assist women . . . so that one woman may aid another in her illness and not divulge her secrets to . . . uncourteous men” who do not take women’s illnesses seriously.

Whether she ever existed is a matter of debate. Some scholars say that the text was too good to have been written by a mere woman, yet one critic maintains that it was so bad that its male author put a woman’s name on it to avoid being identified with it! Trotula’s name is found on the register of citizens of Salerno (home of a medieval medical school that had women on its faculty), and her manual was much read, copied, translated, and adapted, so at least for several centuries she was accepted as a real person.

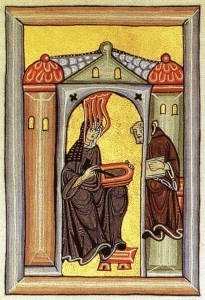

The remarkable Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) didn’t have the benefit of formal medical training. In fact, for most of her life it never occurred to anyone that she would treat patients or even speak with anyone outside a very restricted circle. At the age of eight, Hildegard had entered a strict cloister and was expected to leave her convent alive.

Illness played an important role in Hildegard’s life. She had had visions since she was a child, but did not tell anyone about them until much later. The neurologist Oliver Sacks thinks that these visions were the result of the aura often experienced by people who suffer from migraine.

Hildegard tended to fall ill when she didn’t get her own way. When the Abbott refused to allow her to establish her own convent, she fell ill with an apparently life-threatening sickness. When permission was granted, she recovered instantly. As prioress, Hildegard was responsible for health-care duties at her abbey.

Hildegard tended to fall ill when she didn’t get her own way. When the Abbott refused to allow her to establish her own convent, she fell ill with an apparently life-threatening sickness. When permission was granted, she recovered instantly. As prioress, Hildegard was responsible for health-care duties at her abbey.

Her first two books concern medical therapies, and this subject is treated in later works as well. Hildegard was quite interested in reproduction and in female sexuality. She stood accepted theories on their head, claiming that women were more passionate than men, and also that long-standing taboos against menstrual blood really should be applied to semen instead. Traditional medical theory said that men were hot-natured and women cold-natured; Hildegard insisted on the opposite, saying that the warmth of the womb is what ultimately gives life to the fetus.

She assigned the date of the onset of the menses at 15, and its cessation at 50 (roughly the same time-span as in the modern West).

Hildegard is also responsible for the first known description of female orgasm in Western literature. Characteristically, she assigns to women an active role in sexual activity:

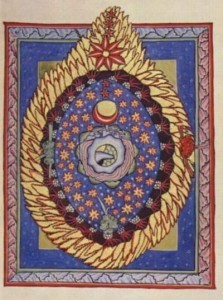

The—er, cosmos, according to Hildegard

“When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man’s seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman’s sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.”

Elsewhere, Hildegard describes women more passively, saying that a woman during intercourse is similar to “the threshing floor pounded by many strokes [or] . . . land under the plough.”

Where would a woman cloistered for all of her early life (and much of her middle age) acquire such knowledge? Eventually eighteen women joined Hildegard in her enclosure, and it is possible that their conversations enlightened Hildegard about life outside the convent walls. Also, the abbey at Disibodenberg could have supplied texts for her to read during and after her enclosure.

Hildegard had more to struggle against even than the average woman of her time, and her vast store of knowledge and the intricately-composed texts and illustrations that she left behind were the result of an individual whose achievements and courage have rarely been matched.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently Dark of the Moon (Harcourt) and The Sherlock Files series (Henry Holt). She lives in Nashville, TN, where until recently she taught Italian, Humanities, and Women’s Studies at Vanderbilt University.

October 18, 2012

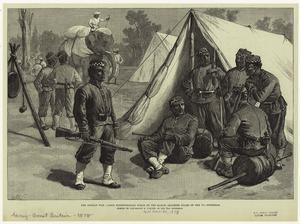

Déjà Vu All Over Again: Attack on the British Garrison in Kabul, 1878

by Pamela Toler

Cabul Expeditionary Force. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

As I believe I mentioned last month, the British government in India was always paranoid about the possibility of Russian influence on the northern border of Afghanistan. (Some of the most paranoid even thought the Russians were behind the Indian Mutiny of 1857. *) In 1878, the amir of Afghanistan pushed British buttons when he accepted a Russian mission to Kabul, but turned a British envoy away at the Khyber Pass. As predictable as Pavlov’s dog, the British invaded.

With the signing of the Treaty of Gandamak on May 26, 1879, the Second Anglo-Afghan War appeared to be over. Britain came out of the war with the right to install a British Resident in Kabul: a British official who would direct Afghan foreign policy in exchange for British support and military aid. Like other South Asian rulers before him, the Afghani amir retained the appearance of independence but had a golden collar around his neck. It looked like British worries about Russian were over.

The new British resident, Major Pierre Louis Napoleon Cavagnari**, arrived in Kabul in July. On September 3rd, Afghan army, preferring independence to British aid, mutinied against the amir who had sold them out, attacked the British Residence, and killed Cavagnari and his staff.

The army of invasion had been dismantled, but a small British force under the command of then Major Frederick Roberts had remained in the field to police Britain’s newest imperial acquisition, the Kurram Valley. Roberts marched the Kabul Field Force into central Afghanistan, defeated the Afghan army at Char Asiab, and took possession of Kabul in early October.

The ease with which the British occupied Afghanistan was deceptive. By December, Afghan troops had taken to the field once more. Roberts was besieged briefly in his camp at north of Kabul. One British brigade was nearly annihilated at Maiwand. And a garrison of 4,000 was besieged at Kandahar. Roberts’ march from Kabul to Kandahar to raise the siege was followed with intense interest in the British press and made him a hero with the British public.

The Second Anglo-Afghan War ended for the second time September 1, 1880. By many standards, the British won. The Afghanis won, too: the British withdrew and made no further efforts to maintain a British Resident in Kabul.

* This line of thinking seemed to go: “Hmmm. Surely the Indians wouldn’t have rebelled against us on their own. They’re too [fill in the blank with offensive adjective of your choice]. Some European power must have influenced them. Oh yes, of course, the Russians.”

** You’re right. Cavagnari doesn’t sound British. An Italian by birth, he became a naturalized British citizen in 1857.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change. Her most recent book is Mankind:The Story of All of Us–a companion to an up-coming History Channel series.

October 15, 2012

Bonanza denied by pickax and jackass

In 1849 two good-looking, well-educated brothers from Pennsylvania joined the surge of young men travelling westward to “make their pile” in California gold.

ambrotype of Allen and Hosea Grosh

Allen and Hosea Grosh endured hunger, cold, toothache, scurvy, rheumatism and so much dysentery that they had to learn to spell the word diarrhea for their letters home. After a few unproductive years in California, the Grosh brothers crossed the mountains to seek better luck in the territory that would one day be called Nevada.

Allen and Hosea weren’t mere placer miners – scraping at the surface or dabbling in streams – they were chemists and inventors. In between working on a perpetual motion machine they worked out the best ways of extracting silver from the stubborn quartz, for they were among the first to realise Nevada might be richer in silver than in gold. One of their letters home to their father mentions a “monster ledge”. Were they about to discover the massive silver deposit that would later be known as the Comstock Lode and would make Bonanza! a household word?

We will never know, for a few days later the younger brother Hosea put a pickaxe into his foot on the “inner side just under the instep”. At first it seemed like a minor wound but then the wound began to fester and the foot to swell. A poultice of bread and soda was not working fast enough, so Hosea asked for a different poultice of Indian meal. That didn’t work, so a local man recommended a poultice of “fresh cow dung.”

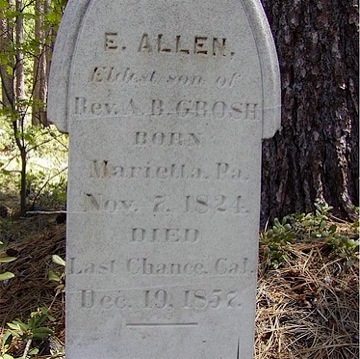

Grosh marker in Nevada with replica pickax

Then occurred the mishap that “sent Hosea out of this world”. While Allen was waiting for a man to bring medical supplies, “the cat jumped on the bed, and in doing so lit with all his weight on poor Hosea’s sore foot. It caused him intense pain.” The next day he died. His devoted older brother stayed long enough to bury him and settle their debts, then he set out for California.

But Allen’s diligence delayed his departure and it was now November. He was travelling with a young Canadian named Bucke, and they might have made it over the Sierra Nevada if not for a troublesome jackass that kept straying from camp at night. The time wasted looking for their pack animal caused the two men to get caught in blizzards on the same mountains that had trapped the Donner Party ten years before. Their matches got wet and their food supply was soon exhausted. Eventually they killed and ate the problematic donkey. Confused by snow, they went up the wrong peak and had to retrace their steps.

Allen’s tombstone in Last Chance

Once again without food or fire, they buried themselves in snow at night to keep warm. With their feet now badly frostbitten they finally managed to make it to a mining camp called Last Chance, literally crawling the last half-mile or so. Bucke let the doctor amputate his feet and he survived, but poor Allen died on 19 December 1857, three months after his younger brother. A poignant letter to their father records that “Mr. Grosh was buried very gently today at ½ past four o’clock.”

The editors of the letters think the Grosh brothers were based too far down the mountain to have discovered the actual Comstock Lode, but if they had lived a few years longer their expertise in chemistry and mining would surely have brought them the wealth and success they longed for.

But their dreams ended in tragedy, all because of the slip of a pickax and the wanderings of a jackass.

The Gold Rush Letters of E. Allen Grosh and Hosea B. Grosh edited by Ronald M James and Robert E Stewart are available in hardback and Kindle formats.

My own historical fiction book for kids also mentions the Grosh Brothers and gives more background to some of the colorful characters who lived on the Comstock in the early 1860s, including Mark Twain. The Case of the Deadly Desperados is out now.

October 13, 2012

A Random Collection of History Links

By Holly Tucker (Editor, W&M)

I’m always tweeting or retweeting links about history and other quirky stories. What would you expect, my Twitter handle is @history_geek.

Here are a few of the best from this past week. Ok, the one about showering is not history related…but come on, tell the truth, how many of you writers work all day long in your pajamas? [Me? Looks around sheepishly, raises hand.]

RT @historybeagle: The 17th C recipe collection of the famed salonnière Madame de Sablé: http://t.co/JnHz4pe2”

RT @smithsonianmag: Are you up for the challenge of the great #American history #puzzle? http://t.co/vmFwBit6

America’s First Pop Psychologist by @jack_elhai http://t.co/ewf6ac5J

RT @bbc_future: LED at 50: An illuminating history by the light’s inventor. http://t.co/rLKAAVmw

RT @boraz: Showering is Overrated http://t.co/ZWdZix3L

Theatres of Anatomy http://t.co/glenYtbS

Maybelline Kissing Potion, 1970s http://t.co/sSka3i3A

Could an app predict the future one day? via @bbc_future ‘s http://t.co/obRE5gNV

Thelonious Monk, Live in Oslo and Copenhagen (1966) http://t.co/ynx919S0 @openculture

October 9, 2012

Theatres of Anatomy

I was recently lucky enough to visit for the first time two historic anatomy theatres: the oldest permanent structure, the Padua anatomy theatre of 1594, and the 1638-39 one in Bologna. Before 1594, anatomy theatres were temporary structures, in some cases erected at the expense of the professor performing the dissection. On the tour I was leading, we went to Bologna first. I had done quite a build-up to this visit, inviting people to think about the audiences for anatomy – students? the university? the public? We know that, at some points in the history of human dissection in Bologna, posters went up in advance of a session, and tickets were sold. We also know that the spectacle was so popular that medical students were restricted in how many dissections they could attend in the course of their studies. We had thought about the origins of those dissected – normally, criminals – and I had regaled the group with the story of a man sentenced to life imprisonment who was suddenly moved on to the death sentence list because the university was short of bodies for its medical students. While I spoke to the assembled group in the anatomy theatre itself, other people drifted in and sat down to listen to me, as I tried to evoke the atmosphere of a seventeenth-century dissection, talking about the damask curtains, the candlelight and the musical accompaniment. I reminded the group that the wooden flayed men supporting the canopy over the professor’s seat were designed by Ercole Lelli, whose wonderful waxes of bodies they had seen earlier in the trip. Afterwards, the group was buzzing with excitement and looking forward to Padua.

Ah. Padua. Not such a fun experience…. Partly it was because the Palazzo del Bo, where the anatomy theatre is located, is having major repairs done. Also, we were running late, and I may have communicated my concerns about this to the group. Partly it was because this was the one visit we made for which we had to have a ‘local guide’, who did not understand that we had seen a lot of medical history already and ignored the point that we really didn’t need a list of facts and dates.

But mostly, I think, it is simply the anatomy theatre. The experience is very different. You can’t climb up to the higher tiers now, so instead you go in at ‘cadaver level’. Although the theatre can hold around 200 people, it is tiny. The shape, a inverted cone, feels very un-conelike when you are in the position of the body about to be dissected. The brilliance of the architecture and design means that the spectators are really very close indeed to the action, almost on top of it! In contrast with the later Bologna anatomy theatre, there is no decoration; no carvings of flayed men, but also no carvings of the great men of medicine, from Hippocrates and Galen onwards. At Bologna, you feel part of a great celebration of the tradition of western medicine: at Padua, you’re the body on the slab, and there are no artistic decorations to help you forget about it!

America’s First Pop Psychologist

by Jack El-Hai, Wonders & Marvels Contributor

When Joseph Jastrow died in 1944 at age 80, he was almost a forgotten figure in American psychology and certainly an irrelevant one to many minds. Decades earlier he had given up full-time work in academe, and his most recent writing, an analysis of the psychology of Adolf Hitler, had been ignored.

Joseph Jastrow (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet for many years he had been America’s preeminent pop psychologist, finding ways to explain and interpret psychological ideas to lay audiences interested in bringing the wisdom of this new science into their daily lives. Drawn away from experimental psychology by personal tragedies, he wrote popular books and contributed to Harper’s Monthly and other consumer magazines. The Polish-born Jastrow was thus a predecessor of such recent pop psychologists as Joyce Brothers, M. Scott Peck, Wayne Dyer, and “Dr. Phil” McGraw.

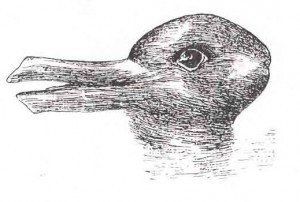

Short and bespectacled, Jastrow was the first American to receive a doctorate in psychology, in 1883. He joined the faculty of the psychology department at the University of Wisconsin. There he built the first psychology laboratory that specialized in investigations of the senses. He examined involuntary movement, stereoscopic vision, deception, hypnosis, the mental acuity of conjurers, reasoning processes, and the formation of judgments. His studies of optical and psychological illusions carried his name around the world, and several of his illusions — still known as Jastrow Objects — continue to appear in psychology textbooks.

By 1900, his passion for experimental psychology had run dry and the stresses of his career brought him a mental breakdown and the need to seek medical care. (A newspaper headlined a story on Jastrow’s troubles as “Famous Mind Doctor Loses His Own.”) After a year away from academics, he focused his attention on popularizing psychology rather than continuing to labor in the laboratory. Later, the death of his son in World War I and his wife’s death added to Jastrow’s depression. He now tapped his talent for presenting psychology to the public, a skill he had cultivated years earlier at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. At that public gathering — the same one at which the serial killer H.H. Holmes found his victims — Jastrow created an exhibit that included participatory activities, including psychological tests that visitors could take on the spot. One of his test-takers was the teenaged Helen Keller, who received from Jastrow the first thorough examination of her sensory faculties.

The Rabbit-Duck Illusion, one of the best known Jastrow Objects. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1901 Jastrow wrote Fact and Fable, the first of his many popular books on psychology. One of his favorite topics was the deceptive performances of mediums and psychics, and he joined with the stage entertainer Harry Houdini in jousting with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and others who believed in the supposed talents of spiritualists. Meanwhile, although Jastrow came off as boring and incomprehensible in the classroom, he developed into an entertaining speaker on the popular lecture circuit. He gained fame for his lectures on “the will to believe,” his phrase for our tendency to let authority and sensationalism persuade us even when scientific evidence suggests we shouldn’t.

Toward the end of his life, Jastrow became a well known media personality. Soon after resigning from his teaching position at the University of Wisconsin, from which he had grown distant, Jastrow began writing a syndicated newspaper column, “Keeping Mentally Fit,” in 1927, and during the 1930s he refashioned his topics for radio audiences. His final books bore such titles as Piloting Your Life, Effective Thinking, and Sanity First — early entries in today’s self-help category. His last volume, Hitler: Mask and Myth, never found a publisher. By the end, audiences viewed his style as old-fashioned and formal, but he introduced countless people to the illuminating potential of the study of human behavior. “There was no exploiting just for the sake of sales or publicity,” one of his eulogists concluded. “Jastrow always left a dignified impression of psychology and did nothing to bring the science into disrepute.” Not all of today’s pop psychologists can claim the same.

Sources:

Behrens, Peter J. “War, Sanity, and the Nazi Mind: The Last Passion of Joseph Jastrow.” History of Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 266-284.

Blum, Deborah. “Mind Tricks for the Masses.” On Wisconsin Magazine, Summer 2010.

Pettit, Michael. “Joseph Jastrow, the Psychology of Deception, and the Racial Economy of Observation.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 43(2), pp. 159-175.

Pillsbury, W.B. “Joseph Jastrow, 1863-1944.” The Psychological Review, Vol. 51, No. 5, pp. 261-265.

October 6, 2012

Dread Death by Purple Snake Poison

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

by Adrienne Mayor (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

One of the most feared poisons in classical antiquity was obtained from the so-called Purple Snake. According to the Roman natural historian Aelian (ca AD 200), this snake from the “hottest regions” of Asia had deep purple body and a head “as white as milk.” It was described “almost tame” and unable to strike with fangs. But if this reptile were to vomit on your leg? The entire limb putrefies and you die, quickly or “little by little.”

Aelian’s Purple Snake had never been identified. Curious, I contacted a herpetologist. He was struck by two details in Aelian’s description: the remarkable white head and the habitat in the “hottest part of Asia.” Aelian’s information must have come to Rome from travelers on the Silk Route. The Purple Snake matches the description of a rare, white-headed viper of China, Myanmar, and Vietnam, unknown to science until 1888. Azemiops feae is the only tropical Asian venomous snake with a distinctive white head. The body, dark blue-black with red bands, appears purple especially when the scales reflect light or if a preserved specimen is observed. A primitive viper with short fangs and small venom sacs, Azemiops is described by herpetologists as “docile but dangerous.”

According to Aelian, collecting the toxins of the Purple Snake for making poison was complex. To extract the venom, you suspend the live viper alive, head down over a bronze pot to catch the dripping poison, which congeals and sets into a thick amber-colored substance. When the snake eventually dies, replace the first pot with another to catch the watery serum flowing from the carcass. After three days, this foul liquid jells into a deep black substance.

These two poisons of the Purple Snake should be kept separate, as they kill in different ways, both dreadful. The black poison causes a lingering, wasting death over years from spreading necrosis and suppurating wounds. The pure amber venom causes violent convulsions. Then, declares Aelian, the victim’s “brain dissolves and drips out his nostrils and he dies a most pitiable death.”

Feeling queasy? That reaction was exactly the intention of poison arrow makers in antiquity. Simply dipping arrows in the pure venom would be deadly enough. Dried crystallized venom can retain neurotoxicity, and the rotting vipers’ body contributed bacterial contaminants to wreak havoc in a puncture wound. The very idea of an enemy supplied with Purple Snake poison was terrifying. And indeed, broadcasting your ghastly poison recipes to potential enemies was an important psychological aspect of biological warfare.

The disastrous result of “vomiting” on a victim described by Aelian probably referred to venom that accidentally dripped into an open sore. Azemiops venom has not been fully analyzed, but it is a hemotoxin with devastating effects and significant necrosis. Notably, in 2012, chemists isolated a novel polypeptide, Azemiopsin, by gel filtration of the venom residues, which they hope may be valuable in neurotransmitter research and biomedical applications.

About the author: Adrienne Mayor is a Research Scholar in Classics and History of Science, Stanford University. She is the author of “Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” (2009); and “The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome’s Deadliest Enemy,” a nonfiction finalist for the 2009 National Book Award.

September 30, 2012

The Ghost of a Murderous Midwife

By Lisa Smith, W&M Contributor

Helen King recently discussed the long history of depicting midwives as murderers. In the lively comments section, Michelle Moon wondered whether midwives were frequently prosecuted for infanticide. In short, the answer is no. But that didn’t mean there weren’t stories! One such murderous midwife, Mrs Adkins, played a starring role in a ghost story, Great News from Middle-Row in Holbourn (1680).

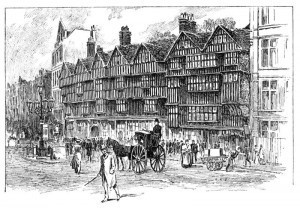

Staple Inn, Holborn, 1900. Middle Row would have stood next to it until the late nineteenth century. Source: Walter Besant, The Fascination of London Holborn and Bloomsbury (Wikimedia Commons and Project Gutenberg).

The pamphlet (Great News) reported that Mrs Adkins’ restless spirit returned about six months after her death. Middle Row no longer exists, but the row of cramped houses was then to be found blocking up the south end of Gray’s Inn Road. Former neighbours in the Row complained of being frightened by “strange Apparations resembling her shape and form”. There were noises, visions, and “Impetuous Groans”, but these “dismal Echoes of some strange Event” were largely ignored.

Then, on Tuesday the sixteenth of March 1679 at nine in the evening, the spirit took on mortal shape, as it “would no longer keep concealed what was the cause of its disturbance”. The servant of the house had been sent upstairs on an errand and was, as you might imagine, surprised to discover next to the cupboard an apparition. The figure that appeared to be Mrs Adkins, who “with ghastly Countenance seemed to belch flames of Fire”. The poor servant was terrified, but the spectre instructed her to be not afraid and asked her to pass on a message to Mary (possibly Mrs Adkins’ grand-daughter): “take up two Tiles in the hearth, and under them should find a board and what she found beneath, that she should bury”. The ghost then “in a Flash of Lightning Vanished”.

Once the maid had recovered her wits, she recounted her experience to her employers. Initially, the master and mistress disbelieved her, but the maid’s continued insisted and the prior reputation of a haunting combined to persuade them to investigate. They found concealed beneath the tiles the bones of two children. Surgeons concluded that the bones had been there for many years, thus clearing the current occupants of any suspicion and suggesting that Mrs Adkins really was guilty. Popular conjecture was that the bodies belonged to “Children Illegitimate, or Bastards who to save their Mothers’ Credits had been Murdered, and buried there”.

In life, Mrs Adkins had been a discreet midwife (“extraordinary subtlety and private policy”), but a somewhat odd character tending towards boastfulness and saying peculiar things. Now it all seemed to make sense, with her discretion taking on a sinister aspect. But “no secret”, declaimed the pamphlet, “can overpass his [God’s] boundless wisdom, nor escape his sight; nay Hell itself has not a depth sufficient to obscund prodigious crimes from him”. Even in death, the midwife’s soul bore the “lasting stain” of murder, and she was compelled to reveal her crime.

A short, but complex, tale: ghost stories are always laden with cultural meanings. Peter Marshall sees this as an example of a religious tale in which God’s power was always triumphant, no longer (as Great News puts it) letting a “Monstrous Crime” remain “masked in Darkness”. Laura Gowing considers the pamphlet within the context of growing fears about infanticide and illegitimacy; Mrs Adkins was depicted as the baddie who aided and abetted women in keeping their nefarious secrets. We might even read the story in terms of Mrs Adkins’ difficult personality. Her oddness in life might have predisposed people to expect her to haunt them in death, a motif that Paul Barber has noted in early modern vampire accounts…

What do you think?

Lisa Smith is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Saskatchewan. She writes on gender, family, and health care in England and France (ca. 1600-1800) and recently taught a course on natural and supernatural worlds in early modern Europe.

Further Reading

Barber, P. Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality (Yale University Press, 1990).

Gowing, L. Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in Seventeenth-Century England (Yale University Press, 2003).

Marshall, P. Mother Leakey & The Bishop: A Ghost Story (Oxford University Press, 2007).

September 29, 2012

Friedrich Miescher and DNA

By Sam Kean

As a young man, Friedrich Miesher had trained to practice medicine in his native Switzerland. But a boyhood typhoid infection left him hard of hearing and unable to use a stethoscope or hear an invalid’s bedside bellyaching. Miescher’s father, a prominent gynecologist, suggested a career in research instead. So in 1868 the young Miescher moved into a lab run by the biochemist Felix Hoppe-Seyler, in Tübingen, Germany. Though headquartered in an impressive medieval castle, Hoppe-Seyler’s lab occupied the royal laundry room in the basement; he found Miescher space next door, in the old kitchen.

Hoppe- Seyler wanted to catalog the chemicals present in human blood cells. He had already investigated red blood cells, so he assigned white ones to Miescher—a fortuitous decision for his new assistant, since white blood cells (unlike red ones) contain a tiny internal capsule called a nucleus. At the time, most scientists ignored the nucleus—it had no known function—and concentrated on the cytoplasm instead, the slurry that makes up most of a cell’s volume. But the chance to analyze something unknown appealed to Miescher.

To study the nucleus, Miescher needed a steady supply of white blood cells, so he approached a local hospital. According to legend, the hospital catered to veterans who’d endured gruesome battlefield amputations and other mishaps. Regardless, the clinic did house many chronic patients, and each day a hospital orderly collected pus-soaked bandages and delivered the yellowed rags to Miescher. The pus often degraded into slime in the open air, and Miescher had to smell each suppurated-on cloth and throw out the putrid ones (most of them). But the remaining “fresh” pus was swimming with white blood cells.

Miescher threw himself into studying the nucleus: a colleague later described him as “driven by a demon. But without this focus, he probably wouldn’t have discovered what he did, since the key substance inside the nucleus proved elusive. Miescher first washed his pus in warm alcohol, then acid extract from a pig’s stomach, to dissolve away the cell membranes. This allowed him to isolate a gray paste. Assuming it was protein, he ran tests to identify it. But the paste resisted protein digestion and, unlike any known protein, wouldn’t dissolve in salt water, boiling vinegar, or dilute hydrochloric acid. So he tried elementary analysis, charring it until it decomposed. He got the expected elements, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, but also discovered 3 percent phosphorus, an element proteins lack. Convinced he’d found something unique, he named the substance “nuclein”—what later scientists called deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA .

Miescher polished off the work in a year, and in autumn 1869 stopped by the royal laundry to show Hoppe-Seyler. Far from rejoicing, the older scientist screwed up his brow and expressed his doubts that the nucleus contained any sort of special, non-proteinaceous substance. Miescher had made a mistake, surely. Miescher protested, but Hoppe-Seyler insisted on repeating the young man’s experiments—step by step, bandage by bandage—before allowing him to publish. Hoppe- Seyler’s condescension couldn’t have helped Miescher’s confidence (he never worked so quickly again). And even after two years of labor vindicated Miescher, Hoppe-Seyler insisted on writing a patronizing editorial to accompany Miescher’s paper, in which he backhandedly praised Miescher for “enhanc[ing] our understanding … of pus.” Nevertheless Miescher did get credit, in 1871, for discovering DNA .

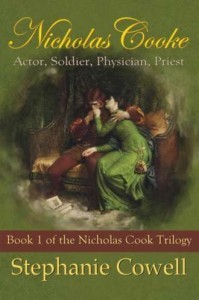

17th-century medicine and me: a novelist’s unlikely tale

Novelists sometimes find themselves writing about areas of which they know little and believe me, I was the last person in the world to write about medicine or science. I had walked out of biology in eighth-grade when my teacher had encouraged us to stick our fingers in a cow’s heart. My average test score in chemistry was a zero and no one could persuade me to study physics. But oddly, many years later, a character in a novel I was writing circa 1600 was interested in those things and I found myself passionately reading piles of research books about 16th-17th century medicine and astronomy. The novel NICHOLAS COOKE: ACTOR, SOLDIER, PHYSICIAN was published by W.W. Norton to wonderful reviews and I was told, actually ended up in a few libraries under early medicine.

Which would have amazed my poor teachers long ago.

In 1600, the telescope and microscope were very new; plague came into the plot, and thereafter a tragedy for my novel’s hero Nicholas and subsequently his search for the cure of it. Instead of looking at science through the bored eyes of an artistic schoolgirl, I saw it from the point of view of a brilliant man who had to understand disease and find its cure.

And like many novelists who discover something through a beloved character’s eyes, there was never enough information for me. Living in New York City, I was able to visit the Arents Collection of the New York Public Library and pore over an original edition of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia with his detailed drawings of lice and fleas, wonderfully appalling considering how many people were hosts to those insects then. (I itch when I look at them even now.) And I went to the rare book room of the New York Academy of Medicine, one of the most interesting research experiences of my life. They found me a small pile of books about the training of a physician in Cambridge circa 1610.

As I said, you never know what your novels will lead you to! You start writing and the characters go off and do unexpected things.

Medical studies in Cambridge in 1610 were more primitive than now as the colleges had neither heat nor electricity. Students ran up and down the quads to get warm before bed. Any conversation and all classes were in Latin.

To quote Nicholas from the novel, “Students attended lectures, the public ones in the Old Schools or private ones in dining hall, chapel, or tutor’s room. We learned by lectures, by disputation with the masters, and by the art of declamation, in which we expostulated upon a chosen subject in a set speech which would display our rhetorical ability and our knowledge of the classical writers. Passionate disputation, with words running like blood, once upon ‘Whether celestial bodies can be the cause of human actions’ (I taking the negative) and then again upon the Platonic thesis ‘That men are nothing else than their souls,’ continued to the great hour of nine at night while the snow fell upon the bridges over the river Cam.

“I studied mathematics, which included cosmology, geometry, and astronomy, and attended lectures on theology and the Code of the Ecclesiastical Law of our realm. Most of my studies, however, were in anatomy, comparative anatomy, dissection, embryology, something of physiology, and a great deal of embrology and the study of pharmacopoeia. The textbooks I had already in my possession: Galen and Hippocrates and the Vesalius De humani corporis fabrica or The Fabric of the Human Body. The third, written perhaps sixty years before, disagreed fiercely with the others……Galen had said that every man possessed an intermaxillary bone. Not finding it, I asked my teacher where it might be, whereupon he angrily answered, “Man had this bone when Galen lived! If he has it no longer, it is because sensuality and luxury have deprived him of it!” For a fee some students and I were given an old corpse to dissect…

“Wainscoted halls glimmering by torchlight, architecture both ancient and contemporary, cloistered gardens and chapels, the river Cam, which ran sweetly behind the colleges under heavy willow trees, and in which, come spring, the students illegally swam. On the riverbank, which we called the Backs, one could watch the swans. The libraries, where we went at dawn and left at dusk, feeling our way down the dim stairs, for no candles were permitted, were serene. The rattle of chained volumes: the leather bindings of well-used volumes; the books of Trinity, of St. John’s, and of King’s. The bitter cold of winter, in which we hacked and coughed through lectures and dissections; the spring, in which corpses were left to be buried and we studied fevers and herbs.”

NICHOLAS COOKE was planned as the first part of a trilogy about the life of a man who is actor, soldier, physician and priest. The second book THE PHYSICIAN OF LONDON was also published by W.W. Norton; it won an American Book Award. I hope to have it as a Kindle book by the end of this year. I am presently writing the third book IN THE CHAMBERS OF THE KING. The three novels take Nicholas from an actor’s apprentice at the age of 13 through the restoration of the monarchy when he is a very old man.

I would love to go back in time and walk through the Cambridge colleges in 1610, and I would love to go back to my high school years and tell my teachers that I ended up seriously studying medicine and wrote a book about it. They simply would not believe me.

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com