Holly Tucker's Blog, page 90

December 1, 2011

The Leper's Legendary Decay

Image Credit: Peter Richards, The Medieval Leper (2000)

Zombies are now a horror staple that spans mediums, and justly so. Zombies combine our intellectual fear of social decay and loss of self with our instinctual horror at the notion of a disease that rots flesh and threatens to consume anyone who dares go near those suffering from it. As contamination spreads, the disease threatens to overwhelm the medical systems which attempt to stand in its way, taxing and eventually exhausting human resources, medicine, and scientific knowledge.

Deep at the heart of what makes zombies send chills up our spines is the knowledge that such a disease is not, in fact, so farfetched.

Indeed, at a not-so-distant point in our past, a disease with striking physiological and narrative parallels to popular zombie myths did exist, and at times its population of sufferers seemed as vast as an apocalyptic zombie horde.

Consider leprosy. In the middle ages, the textual depictions of leprosy acquired depth, providing textured, gut-twisting descriptions in medical texts. The sordid details weren't for entertainment; they were descriptive diagnostic tools intended to give physicians help in identifying, categorizing, and recommending appropriate palliative care for lepers, who were, once diagnosed, condemned to endure their incurable condition and a new position in society as one of the 'dead.'

Avicenna described leprosy as cancer of the whole body. The leprosy we know today is caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis. It is often called Hansen's disease, after physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, who identified M. leprae in 1873.

But the medieval doctor relied only on visible symptoms, and in the case of leprosy, these were highly variable and often masqueraded as other diseases. Addressing this difficulty, Gilbert the Englishman, alive during the late 12th and early 13th centuries, included the diagnostic symptoms of leprosy in his Compendium of Medicine. In his pursuit of detail, we find unintentionally chilling prose that wouldn't be out of place in something Lovecraftian.

The skin would become "lucid…stretched into a similitude to very thin, polished leather." The joints would become distorted, a symptom "preceded by a tickling sensation, as if some living thing were fluttering about within the body, the thorax, the arms, or the lips." Blood drawn from the leper would prove to be thick, fetid, and full of granules. The whites of a leper's eyes would become lined in red, as the eyeballs themselves appeared to protrude from their sockets.

In the 14th century, Jordanus de Turre corroborated these clinical realities. The leper's fingertips would lose sensation. The little finger was the first to go, but the numbness would spread to every extremity. White corpuscles would cover the tongue, and the scalp would become lumpy. The cartilage of the nose would be slowly eaten away from the inside, causing it to sink into the face, and the sufferer's hair on both the body and head would fall out. If it grew back at all, it would be in the form of small, straight hairs barely visible in sunlight, "like pigs' bristles."

Although their accounts were graphic in the service of medicine, it was not medieval authors who built a zombie legend out of the disquieting medical realities of the leper's existence. Many people, like physicians, creatives, and missionaries, had something to gain (or certainly nothing to lose) by playing up the severity of leprosy on an individual and societal level. "With a drop of blood from this little finger," says a leprous little girl in Henri Bataille's late 19th-century play, La lépreuse, "I can kill a hundred, I can kill a thousand." The disease itself could not spread that fast in the flesh, but it certainly did in the 19th-century imagination.

It has fallen to historians to dig out the truth and resurrect the historical medical realities of the leper, and Carole Rawcliffe has contributed a big shovel — Leprosy in the Middle Ages (2006). Her account, like others, suggests that it is difficult to substantiate a medieval paranoia or horror of lepers, or the ways it may have manifested, such as in legal evictions of lepers from cities, or restrictions of their movement within those cities. In the middle ages, the typical lazar house may have been more of a monastery or hospice than an isolated stronghold.

With zombies stepping in this century as our fictionalized symbols of epidemic disaster, the complex and intriguing social and medical history of the leper – more Shaun of the Dead than Dawn of the Dead – can be slowly but surely decoded and viewed through a lens wiped clean of the fog of popular fiction. Good news for the nearly 200,000 sufferers of leprosy that exist today.

Marri Lynn holds an MA in the History of Medicine at McGill University, Montreal (2011). She is currently studying French, while freelancing as a writer and copy editor. You can find out more at her About.me page.

November 30, 2011

Tales of an old English Christmas

by Stephanie Cowell (W&M Contributor)

Some years before I became a novelist, I was a wandering English Christmas minstrel. I gathered legends and customs of Christmas in England from the medieval through the Victorian and put them together in a lively narrative. I added about twelve carols, from the obscure "There is no Rose of Such Virtue as is the Rose that Bore Jesu," to "Deck the Halls" and handed out song sheets.

Some years before I became a novelist, I was a wandering English Christmas minstrel. I gathered legends and customs of Christmas in England from the medieval through the Victorian and put them together in a lively narrative. I added about twelve carols, from the obscure "There is no Rose of Such Virtue as is the Rose that Bore Jesu," to "Deck the Halls" and handed out song sheets.

I was a professional singer then (high soprano) and of course I drew on my love of English social history.

I gave the program in the most interested places (and the audience sang with me, though no one knew "There is no Rose…") In one private party at a jeweler's shop, when we got to the "five gold rings" part of "The Twelve Days of Christmas," the jeweler ran to his safe and danced through the room with a tray of precious rings. At another party, the host had designed a feast to go with the program, including a suckling pig with an apple in its mouth and a sad look on its little roasted face. I almost shrieked. I gave An English Christmas in a historical mansion lit only by candles and felt I had stepped into another century.

Misplaced among my papers is a copy of the script, but reaching back into my memory here are a few of the stories:

The real truth behind the carol "The Boar's Head." Somewhere in the twelfth century a student was walking on a road outside Oxford, reading a sacred book when suddenly a fierce boar rushed from the bushes to attack him. Having no weapon to defend himself, the quick-thinking student stuffed his book into the beast's mouth, thus choking it. He then cut off its head and carried it back to college for dinner. This proves that learning is useful.

Good Queen Bess greatly encouraged the giving of New Year's Day gifts to herself.

During the Puritan regime, Christmas feasting was forbidden. Some took it as a day of fasting and all suggested carols were very depressing, about death and hell etc.

A recipe for gilded peacock. Alas, the details are lost to my memory (I was never much of a cook) but a major newspaper printed part of my recipe and when they asked me what I was planning to make for my own family for Christmas, I said, "Something much simpler."

Wishing you all good cheer and merry wassail this season!

About the author: Historical novelist Stephanie Cowell is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. She is the recipient of the American Book Award. Her work has been translated into nine languages. Her website is http://www.stephaniecowell.com.

November 27, 2011

Writers, What Are Your Goals This Week?

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders & Marvels)

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders & Marvels)

Q: What if all of the writers out there talked shop here on Mondays? What if we also each jotted down our weekly writing goals in the comments?

A: Only great things!

Every Monday, I share my writing accountability goals by email with my writing group. It occurs to me that much of what I write to them, I could also share publicly here. In fact, it might even be a great way for the many writers who are regular W&M readers to get to know each other and to provide welcome encouragement and support.

Here, I'm in the process of revising my next book proposal–which has required tons of work when it comes to structure. My goal this week is think through a few missing narrative connections and to finish up the new chapter descriptions. Next up after that will be to put the finishing touches on the sample chapter…with the goal of getting the proposal out to my editor via my agent by December 7.

Call me superstitious, but I won't say much specific about the topic just yet–other than that the book will be the same type of deeply researched, nonfiction-that-reads-like-a-novel as Blood Work, this time with a focus on science in the French Revolution.

But what I can say right now is that book proposals are a lot of work. I'm on my third, no fourth, iteration of this project. The process was the same, in fact, for Blood Work. Each version of the proposal brought me closer to where I needed to be. But it was not until the fourth round of revisions that I knew that I had nailed it.

It's been a long process–but I feel it in my gut that I'm almost there with this new one. I just keep telling myself that every hour, every day spent hammering out the details now will make my work later much easier. And from past experience, I know this to be entirely true.

Awhile back, I shared a bit about my research flow. More to come. I'll also write more in detail another time about how my writing days are structured (and I write every day…ok, ok, mostly every day). But the one thing that I consistently do at every stage of book writing is to READ.

I spend a bit of time each morning studying other narrative history books. My focus as I read depends on what is preoccupying me in regard to my own writing at that moment. Sometimes it's voice. Sometimes it's narrative detailing. Other times, character development.

And when I'm trying to wrangle my own structure (like now), I outline other books so I can figure out what makes them so good. I just finished up plotting out Deborah Blum's The Poisoner's Handbook and, right now, I'm taking apart Candice Millard's Destiny of the Republic. Both are historical writers whom I respect very much and have the good fortune of meeting in person. My own book will look very different than theirs, of course. But it is incredibly helpful to think through all the different (and successful) ways that other writers craft their nonfiction stories.

At every stage of my writing, I also read a lot about craft. Recently, I've been alternating between two books. The first is StoryCraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction, by Jack Hart. The second, Follow the Story: How to Write Successful Nonfiction by James Stewart. Both have great sections on structure. But Stewart's is especially interesting because he walks his readers through his process for structuring several long-form articles, which are reprinted in the back of the book. I think my writing group and I are going to read the articles together and take things apart on our own over the next couple of weeks.

A special gem of the week was David Dobbs' excellent interview with Rebecca Skloot (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks). David and Deborah Blum are leading a session on structure and longform nonfiction at the upcoming Science Online meeting. You can bet I'll bet there!

Looks like all of us, everywhere, battle the same beasts. And why any writer who is serious about their craft will tell you this is damn hard work.

SO, what project are YOU working on and what do YOU want to accomplish this week? Let's see if we can create a supportive writerly community on Wonders & Marvels!

Image: Amelita Galli-Curci types a letter (ca. 1920). Library of Congress.

November 25, 2011

Rose Tucker, With Thanksgiving

By Holly Tucker (Editor, Wonders & Marvels) I spent this evening in the kitchen with my grandmother. My soulmate, she left this world eight years ago. Not a day goes by that I don't miss her.

I spent this evening in the kitchen with my grandmother. My soulmate, she left this world eight years ago. Not a day goes by that I don't miss her.

Tonight, I taught my daughter how to make my grandmother's dumplings. I know the motions by heart. A large bowl, flour, salt, pepper, eggs. An even larger pot, filled with turkey stock, bubbling furiously. The rolling pin, gliding deftly across the dense, light-yellow dough. Not too sticky, not too dry. A butter knife slices perfect rectangles.

Just as my grandmother did with me, I allowed my eager daughter to roll out the first batch of dumplings–as I hovered nervously. There is an art of dumpling making. It is not a craft for novices. The dumplings have to be just right, not too thick, not too thin.

Ball after ball of dough, dumpling after dumpling cut. I picked up one up and sighed. My daughter gave me a worried look. "Am I doing it wrong?" No, oh darling No.

Feel how soft and smooth this one is? See how beautiful the edges are? I was in my grandmother's kitchen. The alternating green and white tiles on her kitchen floor. The sound of my grandfather listening to Marty Robbins in the front room. The warm smell of Sunday dinner mingling with the pleasant, familiar mustiness of the country home where I spent long summer weeks and every holiday.

My daughter beamed proudly.

I have spent all of my adult life writing and researching the past. But tonight reminded me that if there is ever a past that we must never lose sight of, it is the one we each have lived–and those who have joined us, always too briefly, along the way.

Merci, grand-mère. Tu me manques plus que je ne pourrais jamais exprimer.

November 21, 2011

Women, Death, and the Sacraments

By Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt

"The contagious pestilence, which is now spreading everywhere, has left many parish churches and other benefices in our diocese without an incumbent, so that their inhabitants are bereft of a priest…we understand that many people are dying without the sacrament of penance because they do not know what they ought to do in such an emergency…if when on the point of death they cannot secure the services of a properly ordained priest, they should make confession of their sins…to any lay person, even to a woman, if a man is not present."*

This oft-cited passage speaks volumes about the devastation wrought by Bubonic plague in the late Middle Ages. Medieval Christians, deeply concerned about questions of salvation, believed it absolutely necessary to make a final confession before their death. Yet the swift death (most of the visibly infected who succumbed did not live longer than a week) at the hands of the disease and the overwhelming mortality rates confounded the ability of priests to hear so many confessions. Medieval Europeans understood the moment of death as a vulnerable moment (well-illustrated by the image reproduced here), when demons might tempt the soul of the dying. And so, the Bishop of Bath and Wells bent the rules in a rather astounding fashion. First, he allowed that laypeople could perform this sacrament. This alone was an amazing inversion of medieval hierarchies that invested priests alone with this authority. But then the bishop, in a move that must have produced gasps throughout the sanctuaries of his diocese (priests would have been instructed to read his admonitions aloud), extended that same power to laywomen. The salvation of souls, at least in this instance, trumped any misgivings about the gender of the person exercising this authority.

This oft-cited passage speaks volumes about the devastation wrought by Bubonic plague in the late Middle Ages. Medieval Christians, deeply concerned about questions of salvation, believed it absolutely necessary to make a final confession before their death. Yet the swift death (most of the visibly infected who succumbed did not live longer than a week) at the hands of the disease and the overwhelming mortality rates confounded the ability of priests to hear so many confessions. Medieval Europeans understood the moment of death as a vulnerable moment (well-illustrated by the image reproduced here), when demons might tempt the soul of the dying. And so, the Bishop of Bath and Wells bent the rules in a rather astounding fashion. First, he allowed that laypeople could perform this sacrament. This alone was an amazing inversion of medieval hierarchies that invested priests alone with this authority. But then the bishop, in a move that must have produced gasps throughout the sanctuaries of his diocese (priests would have been instructed to read his admonitions aloud), extended that same power to laywomen. The salvation of souls, at least in this instance, trumped any misgivings about the gender of the person exercising this authority.

Yet this was not the only instance in premodern times of women being entrusted with sacramental responsibility. Evidence from Germany and England also reveals that midwives were allowed to perform emergency baptisms. Worried that vulnerable newborn infants might die before the priest could arrive, civic and ecclesiastical authorities admitted that it was worth jettisoning the rules in order to secure the salvation of these newly-arrived souls. Once again, salvation trumped gender.

Significantly, what links these exceptions to the rule is the specter of death. The presence of women at the moment of possible death from a terrifying disease or at the precarious moment of an infant's birth created exceptional circumstances that invested them with unusual power and authority.

* Ralph of Shrewsbury, Bishop of Bath and Wells, writing in 1349. Reproduced in Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death (Manchester, 1994), 271-3.

Elizabeth A. Lehfeldt is Professor of History at Cleveland State University. She regularly teaches a course on the history of Bubonic plague and writes on the history of gender in Europe between 1400 and 1700.

November 20, 2011

Who "Owns" a Story?

By Tracy Barrett, W & M Contributor

I occasionally get questions from readers of my historical fiction asking why I deviated from the real story of the Minotaur or the Odyssey. By "the real story," what they mean is a familiar telling. But the version that my questioners think is the authentic tale is just one in a long line of tellings of a myth or legend, and my books are merely the most recent addition to that line.

Myths were told orally, most of them for centuries, before someone wrote them down. What that writer set down on paper (or clay, or parchment) was only one version, neither more nor less authentic than any other version that either didn't get written down or whose written form has been lost. Usually the same basic story elements persist from one telling to another, but sometimes they are drastically altered. Look, for example, at three different (ancient) endings to the Odyssey, all found in ancient written sources of equal "authenticity":

Odysseus ruled in Ithaca until the end of his days

being sick of the sea, he walked inland until someone didn't recognize the oar over his shoulder and asked, "What are you doing with that winnowing-fan?"

he sailed through the Straits of Gibraltar and never returned

or the two descriptions of Ariadne's fate after she was abandoned on the island of Naxos by Theseus after he killed her brother, the Minotaur:

she hanged herself

she married Dionysus/Bacchus and became immortal

or three levels of Helen's culpability in the Trojan War:

she went willingly to Troy with Paris

she was abducted by Paris and went to Troy against her will

she hid out virtuously in Egypt, while a phantom double went to Troy.

If the ancients didn't find one version more true, more original than the others, why do modern readers?

In my young-adult novel King of Ithaka, Telemachos is indignant that bards change the details of stories. He is told, "Nobody expects a poet to tell the truth. It's a better story this way." This is even more true when a writer is retelling story that was fictional to begin with. What "authentic" story am I deviating from if I create a centaur sidekick for Telemachos, if I have Ariadne choose willingly to stay on Naxos, if my Minotaur in Dark of the Moon is no monster but a horribly deformed man? I'm not changing the "real" story. I'm making a new one, just as the other tellers before me have done.

November 19, 2011

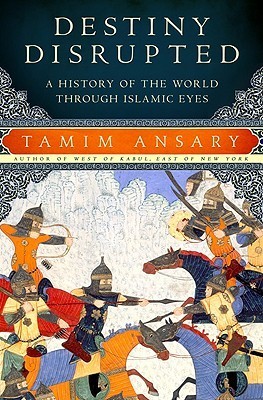

If you only read one book on Islamic history…

By Pamela Toler, W & M Contributor

I've been studying Islamic history for a long time now. (Stops to count on her fingers. Thirty years?? Really?? Counts again. Dang. )

Last year I discovered the best general book on Islamic history I've ever read: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes by Tanim Ansary. I underlined as I read. I annotated. I put little Post-It tabs at critical points, the durable ones so I could go back to key arguments in the future. In short, I had a conversation with that book.

An Afghani-American who grew up in Afghanistan reading English-language history for fun, Ansary argues that Islamic history is not a sub-set of a shared world history but an alternate world history that runs parallel to world history as taught in the West. In Ansary's account, the two visions of world history begin in the same place: the cradle of civilization nestled between the Tigris and the Euphrates. They end up at the same place: a world in which the West and the Islamic world are major and often opposing players. But the paths they take to the modern world, or more accurately the narratives that explain how "we" got to the modern world, are very different. Ansary's book unfolds those two narratives side by side in clear, lively, and often amusing prose. I found his conclusions compelling.

If you're only going to read one book on Islamic history, do yourself a favor: chose Destiny Disrupted. Then let me know what you think about it.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

This post previously appeared in History in the Margins.

November 18, 2011

A Marvelous Dinner Party

Footed plate for Louis XV's "service bleu céleste." Vincennes Manufactory. 1754-5. Boughton House.

Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, had a serious passion for porcelain. She took a leading role in patronage and artistic influence at the French manufactory at Vincennes, which produced the finest objects in the realm in the 1750s. The king provided the economic support to ensure that Pompadour and his court could overindulge in these luxuries. He purchased the manufactory, restricted the movement of workers, and entrusted direction to the head chemist at the Académie des Sciences, Jean Hellot. In return, the manufactory lavished the monarch and mistress with exquisite wares designed in their honor.

One innovation that charmed the court hailed from Europe's leading porcelain manufactory at Meissen in Saxony. Meissen's chemists had perfected a new form in porcelain—the plate—and hatched the novel idea of an entire service of cups, plates, and servers painted with the same pattern. Louis XV asked Vincennes to copy the new form and produce the first French dinner service. For the occasion, Hellot, who was a specialist in paint, experimented with a color never before seen on porcelain wares. He wanted an underglaze rich enough to cover a whole area of the vessel—color had formerly been too thin to coat a large area well and was reserved for small designs or trim. "Celestial blue" (bleu céleste) formed a bright heavenly orb in the center of the plate and proved worthy of special presentation.

Anecdote has it that one evening in February, 1755 the service sat waiting in boxes around the royal dining room. The king planned to unveil it ceremoniously by involving guests in the ritual. He gathered the nobility before the group of crates. Everyone in attendance was asked to open one and unwrap a celestial "masterpiece." This spectacle of the marvelous dinner plate nicely captures the excitement around the art of the table when the full porcelain service first became the must of the fashionable dinner party.

Christine A. Jones teaches French 17th/18th-century literature and culture at the University of Utah. She writes on fairy tales, porcelain, dance, and, most recently, wine.

November 17, 2011

Contributor Q & A: Pamela Toler

Q: Tell us a little bit about yourself. You've lived life both inside and outside academe, as a Ph.D. who now writes freelance. What has the Ph.D. allowed you to do, when it comes to writing, that you wouldn't have been able to do otherwise?

The first thing my graduate school advisor said to me was, "You know there are no jobs, right?"

In some ways it's very freeing to know in your gut that there isn't a job at the end of the process. I took the twenty-year plan for getting my degree, in part because I didn't hesitate to wander down any fascinating by-ways that presented themselves because-hey, no jobs.

Ironically, that dead-end, do-it-because-you-love-it PhD got me my first freelance assignment, and has been opening doors for me ever since.

Q: How did you first become interested in early Arabic science and culture? What has been the most exciting part your research? And the greatest struggles?

The short answer is I found my way to Islamic history via the British Empire. British imperialism leads you inevitably to India, which leads you to Islam, which in my case led me over the Himalayas to the larger Islamic world. I spend a lot of time in eighth century Baghdad and medieval Spain these days

The most exciting part of research for me is finding the point where two cultures connect and change each other. My greatest struggle is flinging myself against the barricades of our collective ignorance about the non-Western world. Quite frankly, Americans as a group aren't very good about learning the history of other countries except at the points where it intersects with our own.

Q: What writers have shaped the way you understand your own work–both in regard to approach and content, as well as how one goes about shaping a narrative in historical writing?

I want to be Barbara Tuchman when I grow up.

Q: Do you read for pleasure? Do you have time to read for pleasure? And what do you love to read?

Do I have time to read for pleasure? No, but I do it anyway. Over meals. In the line at the grocery store. On the bus. To cool down my brain at the end of a long day. If I don't make time to read, I get cranky.

My tastes are broad. I'm too much of a wimp for horror, but pretty much everything else goes. I'm currently reading a literary mystery, a graphic novel, a fat biography, three historical studies dealing with three different periods, a romance (you heard me), two "mainstream" novels, a fantasy, and a Russian classic.

Q: Now the predictable question: If you could catapult yourself into the past for just one day, where would you go? Who would you want to see? And why?

November 2, 1920, the first national election in the United States in which women were allowed to vote. Can you imagine how thrilling it would have been like to vote in that election?

November 14, 2011

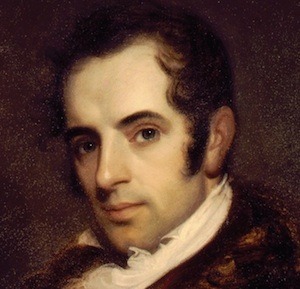

Before they were themselves

In the summer of 1817, two men hiking in the Scottish countryside took shelter from a rainstorm by huddling close together beneath a nearby thicket. One of the men pulled his thick tartan cape over the head and shoulders of the other, protecting them both from the wind and the wet until the storm had passed.

In the summer of 1817, two men hiking in the Scottish countryside took shelter from a rainstorm by huddling close together beneath a nearby thicket. One of the men pulled his thick tartan cape over the head and shoulders of the other, protecting them both from the wind and the wet until the storm had passed.

They were Washington Irving and Walter Scott, although even they hardly knew it yet.

At the time, Washington Irving was just another struggling American expat, desperately trying to beat the post-war economic slump and save the floundering family business abroad. He had always been a lousy student, despite having (eventually) passed the bar, and though he now gamely embarked on a crash course in bookkeeping and business, it would not be enough to save the business from bankruptcy.

And he knew it.

He'd been living on the residual fame of his earlier literary success for years now, having achieved some fame and notoriety as the barely pseudonymous author of A History of New York, the book that gave us the words Knickerbocker and Gotham as synonyms for New York. Following that, he had served as the editor of a reasonably successful American literary journal, mostly confining himself to pirating and reprinting works from England before they were published in America, and writing sentimental biographies of the naval heroes of the War of 1812.

It was hack work, but he didn't honestly have much else to do. And he needed the money.

When his brother Peter's shipping business in Liverpool starting circling the drain, he tried to help. He wasn't much good at it, though, which was depressing, and he took to brief respites of travel during which he might forget his troubles and scribble down half-formed bits of ideas in his journal.

The writing wasn't coming easy for him these days, either.

A friend had given him a letter of introduction to Walter Scott, who was living about twenty miles southeast of Edinburgh, and who had expressed himself an admirer of Irving's History of New York. Irving set out for Edinburgh, determined to make the man's acquaintance if he could.

Scott was not yet Sir Walter Scott. He had not yet published Ivanhoe, or Rob Roy, or Kenilworth. He was widely acclaimed as a Romantic poet, though, and it was in this role that Irving knew him. Admired him. Okay, he idolized him. Irving disliked Coleridge, disliked Wordsworth, disliked Shelley. But Scott, he adored.

So he appears on Scott's doorstep, letter in hand, heart pounding, waiting to see if his idol will deign to see him.

He does more than that. Scott insists that Irving join him and his family for breakfast, then keeps him as a close companion for the next three or four days, introducing him to his daughters, showing him the local landscape, and going over with him the drafts of Rob Roy that he was finalizing at the time.

The incident of the rainstorm, the thicket, and the tartan cape was one that Irving would retell over and over throughout his life. He always felt that Scott had taken him under his wing — literally and figuratively — from that time on, and counted his friendship as among the most important and influential in his life.

More immediately, Irving took heart — and inspiration — from his visit with Scott.

His mood improved, and he finally decided that he would earn his living as a writer, or not at all.

In short, he got down to the business of his life.

Several weeks later, Irving's writer's block crumbled into dust. He stayed up all night and into the next morning, setting down in nearly final draft form the story that would become known as Rip Van Winkle. Shortly thereafter, he began work on The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

Both men would eventually become the literary heroes of their respective countries, inspiring and influencing countless writers and readers who followed in their wake.

Charles Dickens was a big Irving fan, and admitted that he was inspired by the Christmas stories in Irving's Sketches when he wrote A Christmas Carol. Mark Twain would later claim — disparagingly — that Scott's writings formed the foundation of the character of the American South, so widely were they read there.

Scott would receive his baronetcy, and Irving would be hailed as the first true American man of letters, his warm, graceful home in New York's Hudson River Valley becoming nearly as famous as he was.

But they both always remembered their first meeting in the summer of 1817, how instinctively and immediately they became friends, and how much they valued each other's company and support throughout all the long, complicated years ahead.

Beth Dunn is a blogger, novelist, and geek. She writes at An Accomplished Young Lady, travels frequently to the Hudson River Valley, and presents herself unapologetically on the doorsteps of her literary heroes from time to time, quite often with absolutely marvelous results.