Holly Tucker's Blog, page 92

October 26, 2011

The Lost Wife

By Alyson Richman

[image error]"The Lost Wife", began as a personal journey for me. I wanted to write about artists during the Holocaust because I wanted to explore how the creative spirit couldn't be suppressed, even in the most horrific circumstances.

The initial seed of inspiration originated after reading in The New York Times about an artist and Holocaust survivor named Dina Gottliebova. Dina was an art student in Czechoslovakia at the onset of the war, but she and her mother were sent to Terezin, the Nazi-created ghetto outside Prague. While there, she painted postcards that were shipped back to be sold in Germany.

Eventually, she and her mother were transported to Auschwitz. Soon after her arrival, a fellow Czech asked her if she could paint a mural for the children's barrack. She painted "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves" on a single, bleak wall, to give the children a sliver of make-believe in an otherwise ghastly place.

Ironically, the mural ended up saving Dina's life. Josef Mengele saw it and offered to spare Dina and her mother from the gas chamber if she would make portraits of the Gypsies he was "studying."

Dina is depicted in "The Lost Wife" as a historic character, along with several other actual artists who took great risk to document their experiences. Although, Lenka, my main character is fictitious, she shares many of Ms. Gottleibova's qualities. Like Dina, she has a strong spirit, an inextinguishable desire to create, and, miraculously, she survives the war because of her artistic gift.

About the author: Alyson Richman is the author of The Mask Carver's Son, Swedish Tango, The Last Van Gogh, and The Lost Wife. She lives in Long Island, New York with her husband and two children. Visit her online at www.alysonrichman.com.

We have three (3) copies of The Lost Wife to giveaway. To enter, simply leave a comment on this post (below). Sorry, we can only ship winning copies in the US at this time.

Would you like an email notification of other drawings? Sign up for our weekly digest in the sidebar.

October 22, 2011

Louis XIV and his Marvelous Legs

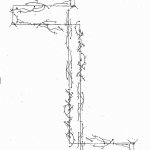

Raoul-Auger Feuillet, Chorégraphie, 1700

By Christine A. Jones (Wonders & Marvels contributor)

The young Dauphin loved the stage. He famously danced the role of the Sun to the delight of the court at the age of 13. Later, when he began his personal reign at the age of 21, he adopted this allegory as his legendary alter-ego. Louis XIV understood that through dance, as through legislation, he could command the aristocracy to move to the beat of his singular drum. He asked dancing masters to create movement for his body and involved his courtiers in spectacles performed at court in which he played the central role—a most creative way to remind them of their place in his universe.

If you pay attention to portraits of Louis XIV and compare them to those of his descendants you'll notice a striking feature of his poses: his legs in tights are often visible. And this is no accident. Gifted with a capacity to learn complicated movements that set him apart from most in the 1680s, Louis used the ability to be steady, strong, and graceful on his feet to his advantage. Dance helped him craft the identity that he sought to project to his people as their absolute monarch.

Hyacinth Rigaud, Louis XIV, 1701

Most importantly, as with everything else he did, the Sun King documented his dancing. Not only did his official dance master, Pierre Beauchamps, codify the kinds of steps he designed for the king on stage, he also named the five basic positions—"first position," "second position," etc.—and charted their succession in primitive notations on paper. In 1700, a student of Beauchamp's named Raoul-Auger Feuillet made history by publishing a book that contained the steps to some of the court's most famous ballroom dances. He called this conceptualization "chorégraphie": Choreography, or the art of describing dance steps in characters, figures, and symbols. Modern dance notation, and with it the ballet, was born.

October 20, 2011

Wandering the Virtual Stacks

By Tracy Barrett, W & M Contributor

I love poking through library shelves, stumbling on books whose existence had never occurred to me; finding, next to the book I'm looking for, an even more interesting one; marveling at titles (a recent favorite: The Thirteenth: Greatest of Centuries—take that, people who call the Middle Ages barbaric!); feeling somehow proud that the book I'm clutching was last checked out during the Second World War.

Now I do most of my research by typing keywords into little boxes on a screen. But it's occurred to me that the way one on-line hit leads to another that leads to another is the same process, and can take you to—well, not to entire books extolling the brilliance of the 1200's in Europe, but to a fact that will make a scene or a character gain that little bit of depth that will bring it to life.

Case in point: the copy editor on my young-adult novel Dark of the Moon pounced on a passage where I said that Theseus' stepfather grated cheese over a bowl of lentil soup. "Did the ancient Greeks have cheese graters?" she asked.

Well, of course they had some way of consuming hard cheese—they wouldn't throw it out. But that got me wondering about how exactly they made it edible, so I set out to look for an answer.

Here's what I learned:

Not only did the ancient Greeks have cheese graters, they looked remarkably like the ones we use today.

A knestris!

The Greek word for "cheese grater" is κνήστις (knestris, in the Latin alphabet) or τυρόκνηστις.

When the women in Aristophanes' Lysistrata go on a sex strike to force their husbands to quit fighting, they renounce a sexual position called "the lioness on the cheese grater."

The spot on your back that you can't reach to scratch is called the "aknestris."

How many of these facts did I wind up using in Dark of the Moon? Only the first, and it all it did was confirm that what I had already figured out must be accurate. But the search gave me a lovely wander through the virtual stacks.

Tracy Barrett is the author of numerous books for young readers, most recently two young-adult novels set in ancient Greece, King of Ithaka and Dark of the Moon. She lives in Nashville, TN, where she teaches at Vanderbilt University.

October 19, 2011

Al-Khwarizmi Does the Math

By Pamela Toler, W & M Contributor

Soviet stamp honoring al-Khwarizmi

Quick: multiply DVII by XVIII. Before you could work the problem you translated it into Arabic numbers didn't you?

The person you can thank, or blame, for your ability to multiply and divide is the mathematician and astronomer Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (ca. 783-847), whose name lives on in a mangled form as "algorithm. (Honest. Take a moment to sound it out.)

We know very little about al-Kwarizmi's life. His name suggests he was born in the region of Khwarazm in what is now Uzbekistan. There are suggestions that he was a Zoroastrian, who may have converted to Islam.

We know a lot about al-Kwarizmi's work as a scholar in al-Mansur's court in Baghdad. He introduced what were then called "Hindu numerals" to the Muslim world. He produced an important astronomical chart (zij) that made it possible to calculate the positions of the sun, the moon and the major planets and to tell time based on stellar and solar observations.

Al-Kwarizmi's most important contribution to science was a ground-breaking mathematical treatise: al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jebr wal-Muqabala. The title translates to The Compendium on Calculation by Restoration and Balancing, but the book is most often referred to as al-jebr, or algebra. His treatise was a combination of mathematical theory and practical examples related to inheritances, property division, land measurements, and canal digging. He was the inventor both of quadratic equations and the dreaded word problem. (Some of his word problems became classics, which meant they were still giving schoolboys grief several centuries later.)

So, the next time you need to calculate how long it will take for two cars to meet in Dubuque if one car leaves Minneapolis going 60 miles an hour and the other leaves Peoria traveling 75 miles an hour? Thank al-Khwarizmi.

About the author: Pamela Toler is a freelance writer with a PhD in history and a large bump of curiosity. She is particularly interested in the times and places where two cultures meet and change.

October 17, 2011

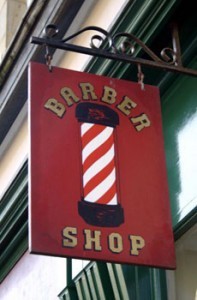

A History of the Barber's Pole

By Lindsey Fitzharris (W&M Contributor)

The history of the barber's pole is as intertwined with the history of the barber-surgeons as the red and white stripes that adorn it. The history of the barber's pole is as intertwined with the history of the barber-surgeons as the red and white stripes that adorn it.

Barber-surgeons were medical practitioners who provided a wide-range of services during the medieval and early modern periods of history. Traditionally, they were trained through apprenticeships, which could last as long as 7 years. Many had no formal education, and some were even illiterate.

The barber-surgeons and surgeons existed separately until 1540, when Henry VIII integrated the two through the establishment of the Barber-Surgeons Company. Although united, tensions between the barber-surgeons and surgeons persisted until the two eventually split in 1745.

Barber-surgeons provided a variety of medical services for their communities. Moreover, because of their varying social backgrounds and relatively cheap prices, they also appealed to a greater number of people in medieval and early modern England. As a result, a person was more likely to visit a barber-surgeon than a physician during his or her lifetime.

So, then, what could a barber-surgeon do for you?

The barber-surgeon's tasks ranged from the mundane—such as picking lice from a person's head, trimming or shaving beards, and cutting hair—to the more complicated—such as extracting teeth, performing minor surgical procedures and, of course, bloodletting. It is this last service which epitomises the barber's pole.

The original barber's pole has a brass ball at its top, representing the vessel in which leeches were kept and/or the basin which received the patient's blood. The pole itself represents the rod which the patient held tightly during the bloodletting procedure to show the barber where the veins were located. The red and white stripes represents the bloodied and clean bandages used during the procedure. Afterwards, these bandages were washed and hung to dry on the rod outside the shop. The wind would twist the bandages together, forming the familiar spiral pattern we see on the barber poles of today.

The original barber's pole has a brass ball at its top, representing the vessel in which leeches were kept and/or the basin which received the patient's blood. The pole itself represents the rod which the patient held tightly during the bloodletting procedure to show the barber where the veins were located. The red and white stripes represents the bloodied and clean bandages used during the procedure. Afterwards, these bandages were washed and hung to dry on the rod outside the shop. The wind would twist the bandages together, forming the familiar spiral pattern we see on the barber poles of today.

After the establishment of the Barber-Surgeons Company in 1540, a statute was passed that required barbers and surgeons to distinguish their services by the colours of their pole. From that point forward, barbers used blue and white poles, while surgeons used red and white poles.

Today, red, white and blue barber poles are often found in the United States, although this may have more to do with the colours of the nation's flag than anything else. Some interpretations posit that the red represents arterial blood, the blue represents venous blood and the white represents the bandages. Spinning barber poles are meant to move in a direction that makes the red (arterial blood) appear as if it were flowing downwards, as it does in the body.

Happily, the only thing your barber is likely to cut on your next visit to his shop is your hair! Or so we hope…

*This article originally appeared on The Chirurgeon's Apprentice.

About the author: Lindsey Fitzharris received her PhD in the History of Science, Medicine and Technology from the University of Oxford in 2009. She is currently a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. Her project focuses on aspects of 17th-century surgery. Read more gory stories on her website: http://thechirurgeonsapprentice.com.

October 14, 2011

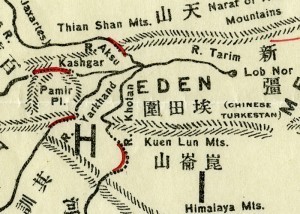

The Problem of Scope

1914 Map of the Garden of Eden in outer Mongolia, by Tse Tsan Tai

My first book, Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, is a history of people who've looked for the Bible's Garden of Eden on Earth. They all start with the same four verses of Genesis and all end up at a different place. Each chapter of my book follows a different theory. I organized the book chronologically, so I could let history and context help move the story along. The variety of interpretations was part of the larger story I wanted to tell.

But just how large was the story? One of my Eden-seekers, a Chinese Christian exiled in Hong Kong during World War I, tried to overthrow China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing. (His Garden of Eden was in outer Mongolia.) How much did I need to know about Chinese dynasties? Another, the first president of Boston University, believed adamantly that the Garden of Eden was at the North Pole. What did I need to know about 19th century polar exploration? My mentor, biographer Patricia O'Toole, always soothing, shared with me her "rule of three." For an event you know nothing about, read three major works about it, ideally from different perspectives, and then move on. With 14 chapters each with numerous background events, I had enough reading for three years.

Even so, in talking about the book, I come up against holes in my knowledge. I quoted the prolific St. writing that Genesis should be taken literally; apparently he later wrote that Genesis is an allegory. Fair enough. My expertise isn't in Augustine, it's in the search for the Garden of Eden—obscure though that may be. I had to reconcile myself to the fact that I can't read everything.

How do you decide what is "foreground" and what is "background" in your story? Do you think of yourself as an expert?

Brook Wilensky-Lanford is the author of Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden, which was a New York Times Editors' Choice in August. Her reviews and essays have appeared in Salon, Lapham's Quarterly, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Boston Globe. A graduate of Columbia University's nonfiction writing MFA program, she lives in New Jersey.

October 13, 2011

COSMIC NUMBERS: The Numbers That Define Our Universe

By James D. Stein, author of COSMIC NUMBERS: The Numbers That Define Our Universe

Ever since the development of the slingshot – and possibly even before that – war has acted as a spur for technology. Sometimes this actually works out reasonably well – the jet plane was developed during World War II and became a staple of military aviation during the Korean War. From there it wasn't long until commercial aviation took advantage of the gain in speed afforded by the jet engine.

Ever since the development of the slingshot – and possibly even before that – war has acted as a spur for technology. Sometimes this actually works out reasonably well – the jet plane was developed during World War II and became a staple of military aviation during the Korean War. From there it wasn't long until commercial aviation took advantage of the gain in speed afforded by the jet engine.

Pure science, however, generally sits on the sidelines during a war – which makes the story of Karl Schwarzschild even more surprising. Schwarzschild was a distinguished professor at the University of Gottingen, specializing in what we now call astrophysics. When World War I broke out, Schwarzschild volunteered for service, and was eventually sent to the Russian front.

Schwarzschild managed to obtain a copy of Einstein's just-published Theory of General Relativity (not the typical reading material of the average soldier), and not only managed to digest it, but became the first person to obtain a solution to the equations that are the heart of the Theory. Sadly, Schwarzschild died of an autoimmune disease shortly thereafter.

The Schwarzschild radius measures the size of a black hole of a given mass. If all the mass of the Earth were concentrated sufficiently to form a black hole, its radius would be about a centimeter. Although there are as yet no technological developments which utilize a black hole, physicists have speculated that black holes may possible be used either as time machines or as ways to provide short cuts from one part of the Universe to another.

About the author: James D. Stein is a past member of the Institute of Advanced Studies and is currently a professor of Mathematics at California State University (Long Beach). His list of publications includes: How to Shoot from the Hip Without Getting Shot in the Foot (with Herbert L. Stone and Charles V. Harlow); How Math Explains the World (a Scientific American Book Club selection); The Right Decision (also a Scientific American Book Club selection); and How Math Can Save Your Life. He has been a guest blogger for Psychology Today and his work has been featured in the Los Angeles Times. He lives in Redondo Beach, California.

October 12, 2011

Shame the Devil

By Debra Brenegan

In the mid-1800s, many women had one career objective – marriage. With few opportunities for higher education and adequate-paying jobs, it made sense that women focused on marriage as a means to future survival.

Enter Fanny Fern, the highest-paid, most-popular writer of the 1850s and 60s.

Fern (who most of us have never heard of) was admired by Nathanial Hawthorne, served as Walt Whitman's literary mentor, outsold Harriet Beecher Stowe and played the part of nineteenth-century "Oprah" to her hundreds of thousands of fans.

When Fern wrote, people paid attention. They adored her spunk and sarcasm, her grit and courage. So, when Fern wrote in one of her weekly New York Ledger editorial columns that "marriage was the hardest way to get a living," people took notice. Fern was no stranger to marriage. She was widowed once, escaped a second abusive marriage and eventually married a third man eleven years her junior.

She had learned a few lessons along the way. First, that men of her time handled the money – not because they were better at it (her first husband amassed loads of bad business debt), but because they had the legal right to. Likewise, women had no legal right to their children (even if a husband turned out to be abusive). Lastly, if a woman happened to have a career of her own, her husband could legally make all decisions regarding that career, including if and when said career would end.

Fern had been burned by the social and legal constraints of the day and wrote columns advising women to make their own ways in the world, to embrace education and non-traditional careers as a final solution to personal survival. Hence her famous words about marriage . . . and the fact that she married for the third and last time only after she penned one of the country's first prenuptial agreements, which her egalitarian husband happily signed.

Debra Brenegan is an Assistant Professor of English and Women's Studies at Westminster College. Her historical novel, Shame the Devil, is based on the remarkable and true story of Fanny Fern.

October 11, 2011

Conisbrough Castle, Yorkshire

By Charles Stephenson

By the second half of the 12th century, great towers were becoming ever more architecturally exuberant. One famous example is the whimsical keep built in the 1160s by King Henry II (1154-89) on the Suffolk coast at Orford. Another is the tower built a decade or so later at Conisbrough by the king's illegitimate brother, Hamelin. Conisbrough had been established soon after the Norman Conquest by William de Warenne. It had come to Hamelin, probably in 1164, by virtue of his marriage to Warenne's great-granddaughter, Isabel, along with the rest of the Warenne inheritance and the title of Earl of Surrey.

Henry's tower at Orford is polygonal, with round rooms on the inside, and is supported on the outside by three great buttressing towers. Hamelin's keep at Conisbrough has similar round rooms and six exterior buttresses, while its exterior is completely cylindrical.

Historians were once inclined to interpret these features as experiments in military science, intended either to deflect missiles or to provide more angles from which to launch them. More recently, Orford has been shown as something altogether different: a playful exercise in geometry. Conisbrough would seem to be a building in much the same mold. Such towers, because of the thickness of their walls, had an inherent resilience, and therefore were of military value. But they were also homes for the super-rich, designed by masons who prized inventiveness for its own sake.

Excerpt from Castles - pages 74-75

About the author: Consulting editor CHARLES STEPHENSON is a historian and writer, whose recent military titles include: Servant to the King for His Fortifications; Paul Ive and the Practise of Fortification; The Admiral's Secret Weapon; Fortifications of the Channel islands, 1941-45: Hitler's Impregnably Fortress; and The Fortifications of Malta, 1530–1945. He is currently working on a history of the Italo-Ottoman War of 1911–12.

October 10, 2011

Arresting Beauty: Julia Margaret Cameron

Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die

By Beth Dunn (Wonders & Marvels Contributor)

I longed to arrest all the beauty that came before me, and at length that longing has been satisfied."

-Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron was widely regarded as the ugly duckling of her family. Born in India into a clan of famously beautiful women, the daughter of a British officer of the East India Company, Julia was always considered plain and uninteresting.

And indeed, for most of her life, she seemed destined to bear this out. She was married early to a man twice her age, and they continued to live quietly in India for the first ten years of their marriage. Then he retired and they returned to England, where they settled into the next chapter of the comfortable, if unspectacular existence that had been charted out for her.

But then, on her 48th birthday, Julia received a camera as a gift from her daughter. And at that, she was off and running.

It wasn't particularly easy to be an amateur photographer at the time. Materials were costly, models were hard to come by, and the laborious process of developing and printing the work involved long hours and at least a passing fondness for chemistry.

But Julia was fortunate in these things — she had money, she had time, and she access to models by way of her own children and servants, and even to celebrities by way of her sister, who hosted a regular salon in Kensington that brought the cream of the literary and artistic world together on a regular basis.

Annie Philpot

Her portraits were ethereal, soft-focus, and sensual. She produced close-cropped portraits of children and young women, as well as dreamy allegorical and historical tableaux, all in the pursuit of "arresting beauty," as she would write later, as if she wanted only to preserve her subjects in amber for all time.

And of course that's why I love 19th century portrait photography — because it does preserve the faces of the past with an immediacy and an intimacy that even the best oil or pastel can't give you. Most portraits from this era, in fact, can give you that startling jolt of recognition, of seeing human eyes peering back out at you from the past, which makes old photography so compelling.

But Julia Cameron's photography takes it a step further, because her work allows you to see into the mind of the person standing behind the camera.

You have an absolute sense that here is somebody who knows what she is trying to capture, and she's willing to go to any lengths necessary to get it down, to lock it in time, and save it for future eyes to see, to marvel at, to comprehend.

While much of Julia's work survives today because she was meticulous about registering and copyrighting all of her work, much of it has also been preserved because of its subject matter.

In many cases, her portraits of the great figures of the day are the only — or in some cases, the best — that survive. Ellen Terry, Charles Darwin, Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, William Rossetti — her lens opened and closed on a brief moment of time in each of their fascinating, turbulent lives.

Sir John Herschel

She found a friend and mentor in Sir John Herschel, son of the famous astronomer of an earlier generation, who introduced her to the intricacies of photography and who shared with her the very latest scientific advances in the new medium. She took his portrait, too.

It took almost one hundred years for Julia's work to begin to receive the recognition it deserved, when a 1948 book celebrated her early contributions to the field.

Prior to this mention, she had been included in the 1886 Dictionary of National Biography, in a brief sketch of her life that was written by her niece and frequent model, Julia Prinsep Stephen, who would later become somewhat better known as the mother of Virginia Woolf.

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has an extensive collection of Julia Margaret Cameron's work, most of which you can access and browse . The V&A will also feature works by Julia Margaret Cameron in an exhibit to celebrate the new Photographs gallery, opening on October 24, 2011.

(Hat tip to Essie Fox, The Virtual Victorian, for reminding me of Julia Margaret Cameron's work, and for the news about the upcoming exhibit.)

Beth Dunn is a writer and novelist with a fierce attachment to 19th century history, literature, and decorative arts that is rapidly approaching the obsessive. She blogs at An Accomplished Young Lady, where she generally lets it all hang out. I mean. In a totally appropriate, 19th-century kind of way.